'' PARADOX OF DISTORTIONS ''

PHOTOGRAPHER ANDRE KERTESZ

PHOTOGRAPHER ANDRE KERTESZ

PHOTOGRAPHER

ANDRE KERTESZ

PARADOX OF DISTORTIONS BY ØIVIND STORM BJERKE'S

PARADOX OF DISTORTIONS BY ØIVIND STORM BJERKE'S

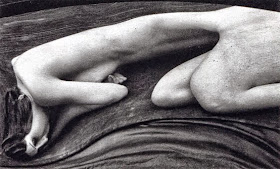

The nudes

from 1933, which are now presented under the title “Distortions,” are united

with Kertész’s production as one of a number of experiments he conducted with

optical distortions, as the result of mirroring in various materials.

Kertész’s awareness of how distortions of natural forms could create

interesting abstract and confusing patterns that dissolved an object was

raised when he photographed a swimmer in 1917.

The first

description of this type of pictures as “Distortions” is from 1939 and is found

in an article called “Paradox of a Distortionist” in the photo periodical

Minicam. In the critique, the pictures are upheld as those, which had

established Kertész as a recognised master. Kertész describe the images as

“Distortions” himself when he publishes the article “Caricatures and

Distortions” in the periodical The Complete Photographer in 1941. Kertész’s

“Distortions” was published as a book in 1977 with a preface by the critic

Hilton Kramer, who at the time was the chief critic at the New York Times.

Kertész had a

well-developed sense for oddities and often gave his pictures a humoristic

turn. It is therefore not surprising that he in 1933 published two photographic

series in the humour magazine Le Sourire. The first was printed March 12, and consisted

of twelve images. The reality we meet is, in other words, “surreal.” Later that

same year, in September 1933, Kertész published another five of the pictures

under the headline “Kertész et son miroir” in the periodical Arts et Métiers

Graphiques.

That Kertész

placed the pictures highly amongst his production is evident as he included a

selection of them in his first solo show in New York at gallery PM in 1937. The

pictures were grouped together with images where he had photographed objects as

a clock and a vase with a flower distorted in a mirror, under the collective

title Grotesque. The pictures immediately raised adoration and were plagiarised

by a number of photographers.

The series

emerged in a short span of time in the spring of 1933, and it is one of the few

times in which Kertész worked in a studio – his preferred fields of production

were streets, parks, public places and interiors such as scenes where life

played itself out in all its ordinariness. Kertész only exceptionally

photographed nudes, and characteristically enough, the nudes he is most known

for are not traditional nudes in the extension of the painterly tradition of

classical portrayals of the body.

The pictures were taken with the help of three mirrors and

an older and a young model. He used a large format camera with a zoom lens.

Kertész took two hundred takes. At the same time as the pictures can be argued

to constitute a particular event in Kertész’s production, the images include

all those elements that we can connect with what is idiosyncratic with

Kertész’s style in his use of light and shadow, distortions and deformations as

a result of reflections, mirroring and shadow play and the isolation of details

that function as eye-catchers. The interpretations of these elements in

Kertész’s pictures can be connected to the experience of the destabilisation of

a realistic image of the world, in the manner of traditional photography.

Kertész’s use of mirrors contradicts the traditional understanding of mirrors

as something that recreates a motif – reflects it. In Kertész’s mirrors, the

motifs are rather partly unrecognisable, even if you don’t loose touch with the

recognisable, as bodily details are recreated with utter precision and draws

the spectator back to the motif. Kertész plays with, and partly ionises, the

idea that what we see in photographs is real. Rather than seeing the images as

studies of the body, we may see them as studies of how the conditions in which

we study an object affects our perception of it and how vulnerable we are also

in our meeting with the photograph.

Kertész’s nudes can be read in a range of different

discourses. One of them is to read them as comments on the nude photograph’s

traditional functions, which to a considerable extent highlighted the female

body as the incarnation of harmonic and beautiful form. The pictures may also

be seen as an ironic comment on how the female body depicted as a sexual

object, had been a primary motif for photographers through the history of

photography.

In the captions that accompanied the pictures published in

Le Sourire, the photographs’ relationship to contemporaneous painting and

sculpture are pointed out, and the forms in Kertész’s pictures can be

associated with the rubber- and amoeba like bodily forms to be found in the

work of artists that worked with organic forms in the 1930s, the most known

being Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore. Salvadore

Dali had painted objects and natural forms that undergo metamorphosis. Also

Hans Arp’s organic sculptured objects are a relevant reference. As early as

1926, Kertész had created one of his most famous photographs, where a model

that lies on a couch, imitates the distorted forms in a markedly abstracted

sculpture on a pedestal next to the couch. In a photo historical context, it is

natural to place Kertész’s nudes in line with later experiments by Brassaï,

Hans Bellmer and Paul Strand, wherein different forms of manipulation created

distortions of forms.

Kertész never became a member of the Surrealist movement,

but it is natural to see his “Distortions” in line with the movement. We find

one of the few direct contacts with the Surrealists when Kertész in the May

issue of the periodical Bifur, which was edited by Georges

Ribermont-Dessaignes, who was an opponent of André Breton, published three

photographs.

It is naturally not a coincidence that Kertész uses the

female body for his experiment, and in several of the pictures, he focuses on

details, that to a considerable extent, identify women’s gender in a

metaphorical and literal sense. Representations of bodies are never neutral,

but express comprehensions of the body either from an anthropological, social,

functional, psychological or an aesthetic perspective.

Kertész’s “Distortions” has been frequently used by writers

who have dealt with the portrayal of women in modern art, often from a

psychoanalytical or feminist perspective. It is undoubtedly interesting how

Kertész uses the body as an object in exploration with optical effects. By

detaching the body from the usual perception of it, the body is estranged and

perception itself is thereby placed in focus. They are also anonymised by the

fact that the pictures can hardly be understood as psychological studies of the

models’ states of mind or personalities. The psychological aspect of the

pictures rests on the photographer in the question – what is his intentions

with the distortions – is it to say something about a comprehension of women,

being either his own or a comprehension in society that he wishes to convey,

and possibly comment on? Kertész’s pictures can also be read as a comment on

the space women occupy; a space which is completely destabilised due to the use

of mirrors. Usually, we have no problem with identifying the physical frame

around the body, but here it is not the body that is photographed, but the

reflection of it in its physical surroundings. In that sense, one may argue

that the pictures are not at all about the body, but about the disintegration

of a spatial perception to which one has become accustomed. In that sense the

pictures can be argued to have developed from the Cubists’ deconstructed and

fragmented spaces. The ruling disorder becomes an attack on the endeavour to

instil the human body in a lucid space, which provides it with a defined place.

Few photographs from the 1900s are better suited to provide

one with an understanding of the different means to treat the photograph than

“Distortions.” They are photographs that almost demonstratively place the

question of what it is that the pictures represent; why they are taken; how

they are taken; in which context they have been presented and, not least, how

the context in which we see them can affect how we understand the pictures.

Between 1928 and -32, Kertész was married to Rózsa Klein

(1900 – 1970). She came to play a considerable role in Kertész’s life, both as

a urger privately and as the one who provided for their livelihood through

large parts of the difficult years Kertész was to experience after the couple

moved to New York in 1936.

In 1936, Kertész secured a contract with the photography

agent Keystone. In light of the anti-Semitic atmosphere that spread through

Europe, the relocation to New York was an act that probably saved his life.

Despite of this, Kertész came to describe the following years as one long

disappointment.

Kertész’s name was known in the USA before he got there.

Photographs were shown for the first time in New York in 1932 at gallery Julien

Elvy in the exhibition “Modern European Photography,” where he showed 23

photographs. Through the exhibition and through his extensive publishing, he

was a well-known name in the inner circles of the world of photography and he

had all reason to believe that he could establish himself in New York. The

first years in New York, he became close to Baumont Newhall, who worked for the

Museum of Modern Art and arranged the important exhibition “Photography 1839 –

1937” where Kertész was represented. The book, which accompanied the

exhibition, is one of photo history’s most central publications. In 1941 he was

represented at the Museum of Modern Art with a picture he bestowed from the

exhibition “Image of Freedom,” which was curated by Edward Steichen, the most

well-known and powerful photographer at the time.

When the book Day of Paris, which was a new selection of

pictures with motifs from Paris that was given a dynamic and contemporary

layout, was published in the USA in 1945, it was well received, and in 1946

Kertész was given his first solo show in an American museum; the Art Institute

of Chicago.

In 1975, a selection of

the pictures was gathered in a book.

Kertész belongs to a generation of photographers who are

first and foremost associated with classical black-and-white photography, but

he also photographed in colours from 1951. He has also made a small number of

Polaroids.

The rediscovery of Kertész began in 1962, when he

participated in the International Photography Biennale in Venice and had a solo

show in Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, which was hidden in South-France

during the war. Consequently, the bridge back to his heydays as a recognised

European photographer was re-established. His definite rehabilitation came in

1964, when John Szarkowski organised an exhibition with Kertész at the Museum

of Modern Art. The following decade, he exhibited all over the world; in Tokyo,

Stockholm, Budapest, London, Helsinki. In 1976, he was appointed as commandeur

des Arts et Lettres, and in 1983, Légion d’honneur. He had an exhibition at

Centre Georges-Pompidou in 1977. In 1984, he transferred all his negatives and

his correspondence to the French state. Mission du Patrimoine Photographique in

Paris, which is now a department of Jeu de paume, www.jeudepaume.org/,

administers the archive. In New York, he established the foundation “The André

Kertész and Elizabeth Kertesz Foundation.” Through the exhibition “André

Kertész of Paris and New York” shown at the Art Institute of Chicago and the

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 1984, his important historical

position was fortified. Later on, the exhibition “André Kertész” at the

National Gallery of Art in Washington and Los Angeles County Museum of Arts, in

2005, with its accompanying publication, was the most important event and

introduction to a renewed international interest and publication of his works.

Kertész is one of the great developers of style in 1900s

photography. For many, the terms “style” and “photography” are almost

contradictory. For most people, a photograph is identical to the motif that is

portrayed. Nonetheless, similar to any pictorial medium, the increasing

awareness of the importance of the pictorial medium itself, and our interaction

with it, is applicable to photography; which technical premises are present;

what is photographed at different times in different societies; how do we

interact with the pictures in different ways and out of the different functions

pictures fulfil, is amongst the questions it is relevant to ask in addition to

focusing on the characteristics that are tied to the pictures’ technological

and physical conditions, material qualities, duplication processes, and their

composition and form. In such a turn from one-sided attention directed at the

motif, to viewing the picture in a broader artistic, cultural, social and

historical context, Kertész’s pictures are clarifying examples.

The example of Kertész provides us with an excellent

introduction to the different institutional regimes 1900s photographers worked

under: the early 1900s’ attempt to integrate photography into the arts on

painting’s premises; the interwar period, and the first decade after the war,

with its emphasis on photography as a medium for documentation and reportage,

until the 1960s, when photography is integrated into the field of arts. Kertész

lived through these phases in his enterprise as a photographer and it is not before

Kertész’ Distortions is placed within a larger art- and photo historical

context that it is possible to understand the exceptional position the works

have achieved.

The text is taken by professor ØIVIND STORM BJERKE'S writing, University of Oslo. Some part of writing had taken off from the

original part.

PHOTOGRAPHER ANDRE KERTESZ