PAINTER ROBERT MOTHERWELL

AMERICAN 1915 - 1991

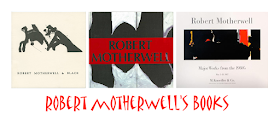

ROBERT

MOTHERWELL: WITH SELECTION FROM ARTIST’S WRITINGS BY FRANK O’HARA …..

A symbolic tale of our times, comparable to the legend of

Apelles' leaving his sign on the wall, is that of the modern artist who, given

the wrappings from issues of a foreign review by a friend, trans forms them

into two collage masterpieces; and who, given a stack of Japan paper, makes six

drawings and on seeing them the next day is so excited by the black ink having

bled into orange at its edges that he decides to make six hundred more

drawings. The collages are N.K.F. Numbers One and Two, the drawings are the

group called "Lyric Suite," and the artist is Robert Motherwell. Does

art choose the artist, or does the man choose art?

Motherwell's

choice is one of the most fascinating in modern art. As a young man of

twenty-five, a university student who majored in philosophy, he decided to

devote himself completely to painting, a decision which at the time held

promise of little but hard work and probable discouragement. Yet, a few short

years later, he was to find himself one of the leading figures in the greatest

revolution in modern art since cubism, abstract expressionism.

Recently, in

a television interview, Robert Motherwell remembered the aims of the early

period of abstract expressionism as being "really quite simple in a way,

almost too simple, considering what has happened in the last twenty years. But

really I suppose most of us felt that our passionate allegiance was not to

American art or in that sense to any national art, but that there was such a

thing as modern art: that it was essentially international in character, that

it was the greatest painting adventure of our time, that we wished to

participate in it, that we wished to plant it here, that it would blossom in

its own way here as it had elsewhere, because beyond national differences there

are human similarities that are more con sequential . . (bibl. 36).

The measure

of the success of the abstract expressionist artists may be gauged by our

response to the movement's ethical stand today it seems an inevitable

development, it is surrounded by an atmosphere of "of course." But in

the late '30s and early '40s there was violent resistance to this

"passionate allegiance." We forget, in the complexity of our present

worldwide artistic and political engagements, that period's artistic and

political isolationism (how controversial then were Gertrude Stein and Wendell

Willkie!), the mania for the impressionist masters, the conviction, where there

was any interest at all, that avant-garde was not only a French word but an

Ecole de Paris monopoly. But the greatest resistance of all came from other

American painters— the regionalists, the social realists and the

traditionalists.

No account of

the period can ignore Motherwell's role as an internationalist. In a sense a

turn toward both revolution and inter nationalism were in the air, for the

various national financial depressions had united most of the Western countries

in crisis, if not in political agreement. And the artists, like the

philosophers and the religious, had been the least economically valued members

of distressed societies.

Without

transition the struggle against Depression conditions be came the struggle

against War. War on such a scale that "conditions" became an obsolete

word, faced down by the appalling actual and philosophical monolith of

historical event. But the artists were not faced down by the war vocabulary.

With the advent of war a hetero geneous number of American artists whose only

common passion was the necessity of contemporary art's being Modern began to

emerge as a movement which, in Boris Pasternak's famous description of a far

different emergency, as he relates in his autobiography Safe Conduct, ". .

. turned with the same side towards the times, stepping forward with its first

declaration about its learning, its philosophy and its art."

Underlying,

and indeed burgeoning within, every great work of the abstract expressionists,

whether subjectively lyrical as in Gorky, publicly explosive as in de Kooning,

or hieratical as in Newman, exists the traumatic consciousness of emergency and

crisis experienced as personal event, the artist assuming responsibility for

being, however accidentally, alive here and now. Their gift was for a somber

and joyful art: somber because it does not merely reflect but sees what is

about it, and joyful because it is able to exist. It is just as possible for

art to look out at the world as it is for the world to look at art. But the

abstract expressionists were frequently the first violators of their own gifts;

to this we often owe the marvelously demonic, sullen or mysterious quality of

their work, as they moved from the pictorial image to the hidden subject.

Motherwell's

special contribution to the American struggle for modernity was a strong

aversion to provincialism, both political and aesthetic, a profound immersion

in modern French culture (especially School of Paris art and the poetry and

theories of the Symbolist and Surrealist poets—conquest by absorption, like the

Chinese), and a particular affinity for what he has sometimes called "Mediterranean

light," which in his paintings seems to mean a mingling of the light of

the California of his childhood with that of Mexico and the South of France.

This affinity may explain somewhat the ambiguity between the relatively soft

painted edges of many of his forms and the hard, clear contour they convey,

especially in the series of "Elegies to the Spanish Republic." He can

employ a rough, spontaneous stroke while evoking from the picture plane with

great economy a precise personal light. There is no atmospheric light in his

paintings; if he uses grey it is never twilight or dawn. One of his important

early paintings is called Western Air (page 13) and the light in it persists in

many later works.

Motherwell

must have shown a surprisingly early talent for art, considering that at eleven

he was awarded a fellowship to the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles (where

Philip Guston also studied briefly). Although he also attended art school at

seventeen, he was not to make the final decision to devote himself to painting

until 1941. The intervening years had been spent largely in the study of

liberal arts and philosophy. He was led by his admiration of Delacroix's

paintings to choose for his thesis subject at Harvard the aesthetic theories

expounded in Delacroix's journals. On the advice of his teachers, he therefore

spent the year 1938-39 in France. Delacroix led to Baudelaire, Baudelaire to

the theories of the French Symbolists and especially Mallarme, and there

followed a close study of the Parisian painters.

Shortly after

Motherwell's return to the United States he moved to New York. He discussed his

first days there in a recent talk at the Yale University Art School:

"One of the great good fortunes I have had in my life,

and there have been several, was that at a certain crucial moment in my life

when I was in my mid-twenties and still hadn't really decided what I wanted to

do, though in another way I'd always wanted to be a painter but through the

circumstances of fate had never known a modernist one ... for better or worse,

I don't know—at a certain moment through a contact with a friend who is now

professor of music at Brandeis University I decided to go to New York . . . and

study with Meyer Schapiro. In those days there was nothing like there is here,

that if you were interested in contemporary art there was a place where you

could go and be oriented The closest approach to it, though he is essentially a

classical scholar, essentially devoted to the premises of art history and so

on, in those days was Meyer Schapiro. And I went to New York and studied with

Schapiro. Also by chance took a room near him and knew nobody in New York

—nearly died of loneliness, at how hard and cold and overwhelming it seemed to

me as a person from the Far West, which is with all its defects a somewhat more

casual and open place.

"And

sometimes at eleven o'clock in the night I would drag the latest picture I had

been making on the side in the most amateurish way around to Schapiro. And one

day in exasperation really, because I had then no conception of how busy people

are in New York, he said, 'It takes me two hours to tell you as best I can what

any painter colleague could tell you in ten minutes. You really should know

some artists.' And I said, Well, I agree . . . but I don't know any.' "

(bibl. 38)

As a child,

Motherwell was haunted by the fear of death, perhaps partially because of his

asthmatic attacks. He grew up during the Great Depression and, no matter what

one's circumstances, one could not help being affected by it. The first foreign

political event to engage his feelings was the Spanish Civil War, that perfect

mirror of all that was confused, venal and wrong in national and international

politics and has remained so. For a slightly younger generation than

Motherwell's, and by slightly I mean only by ten years or so, World War II was

simply part of one's life. One went to war at seventeen or eighteen and that

was what one did, perfectly simple, and one thought about it while one was

about it, or you might say, in it. But Motherwell's ethical and moral

considerations were already well formed by the time that war broke out, and for

him the problems were quite different and also far more shattering

psychologically.

It is no

wonder then that when Meyer Schapiro introduced him to the European refugee

artists who had fled here from the Fall of France, he was strongly drawn to

them, both as emblems of art and also as emblems of experience—an experience

which no American artist save Gertrude Stein suffered as the French themselves did.

Their insouciant survival in the face of disaster, partly through character,

partly through belief in art, is one of the great legends, and it did not

escape him. To recall the presence of these artists is indeed staggering (see

page 74). Motherwell's affinity for French Symbolist and Surrealist aesthetics

made him a quick liaison between the refugees and certain New York artists whom

he scarcely knew at the time. The capitulation of France had brought about an

intense Francophilism among all liberal intellectuals, especially those who

felt strongly about the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War; and the fate of Great

Britain was still in question. It was not too difficult to feel a strong

identification, and of course these artists were already heroes of the modern

artistic revolution; if some of them hadn't invented it, they had certainly

aided, abetted and extended it. In the artistic imagination these refugees

represented everything valuable in modern civilization that was being

threatened by physical extermination. It had never been more clearthata modern

artist stands for civilization.

Modern

artists ideologically, as the Jews racially, were the chosen enemies of the

authoritarian states because their values were the most in opposition, so that

one had a heightened sense, beyond the artistic, of seeing a Lipchitz or a

Chagall walk free on the streets of New York. It is impossible for a society to

be at war without each responsible element joining the endeavor, whether

military, philosophical or artistic, and whether consciously or not. The

perspectives may be different, but the temper of the time is inexorable and

demanding for all concerned. I think that it was the pressure of this temper

and this time that forced from abstract expressionism its statement of values,

which is, and probably shall remain, unique in the history of culture. While

the other protesting artistic voices of the time were bound by figuration and

overt symbolism, the abstract expressionists chose the open road of personal

responsibility, naked nerve-ends and possible hubris, and this separated them

from the surrealists, the Mexican School and the American social realists.

Belief in their personal and ethical responses saved them from aestheticism on

the one hand and programmatic contortion on the other. Abstract expressionism

for the first time in American painting insisted upon an artistic identity.

This, of course, is what made abstract expressionism so threatening to other

contemporaneous tendencies then, and even now. The abstract expressionists

decided, instead of imitating the style of the European moderns, to do instead

what they had done, to venture into the unknown, to give up looking at re

productions in Verve and Cahiersd'Art and to replace them with first hand

experimentation. This was the great anguish of the American artists. They had a

sound theoretical, but no practical, knowledge of the suffering involved in

being extreme; but they would learn. They shot off in every direction, risking

everything. They were never afraid of having a serious idea, and the serious

idea was never self referential. Theirs was a struggle as ultimate as their

painting. A struggle which, in the poet Edwin Denby's description in his rem

iniscence of the '30s, was against ". . . the cliche about downtown

painting in the depression—the accepted idea that everybody had doubts and

imitated Picasso and talked politics. None of these features seemed to me

remarkable at the time, and they don't now. Downtown everybody loved Picasso

then, and why not. But what they painted made no sense as an imitation of him.

For myself, something in his steady wide light reminded me then of the light in

the streets and lofts we lived in. At that time Tchelitchew was the uptown

master, and he had a flickering light."

During this

period Motherwell veered between the opposite poles of the marvelous and the

somber, if not morbid; from Mallarme's Swan, imaged in subtle glacial beauty,

to Pancho Villa's corpse, hanging bullet-riddled beside his live image, in

which pink stains take on the aspect of not-yet-dried blood. Shortly before, in

1941, at the beginning of his painting career he had done three divergent

pictures—JLa belle mexicaine (of his first wife, a Mexican actress), an

imaginary landscape, The Red Sun, and the more purely conceptualized The Little

Spanish Prison. The first owes a great deal to Picasso, the second (page 96) to

the surrealist theory of automatism and especially to Masson, and the third

(page 16) is connected in my mind to the royal House of Orange, a modern

version of Dutch clarity of tone allied with Spanish reserve and elegance. As a

selftaught painter, Motherwell had many avenues open to him, and in beginning

he did not close any of them off as possibilities.

Certain of

the abstract expressionists seem to have burst into paint with an already

emergent personal force from the very first works we know—one thinks

particularly of Motherwell and of Barnett New man. The variety from period to

period in each of these artists en compasses a broadening of technical

resources, as it does in Rothko also, and moves in a steadily rising power of

emotional conviction. They have had a conviction, if not a style, from the

beginning, more ethical than visual, which has left them free to include

anything useful and has guided them away from the peripheral. As has Clyfford

Still, for example, each has chosen on several occasions to make moral

statements in relation to his art, rather than aesthetic ones.

This is, of course, a matter of temperament. The passions of

others of their colleagues have led to far more abrupt and dramatic changes.

Motherwell once remarked that an artist is known as much by what he will not

permit as by what he includes in the painting. One would be hard put to aver

whether Newman or Pollock, de Kooning or Rothko, was more drastic in his

decision between the Dionysian and Apollonian modes of feeling, between

seething impasto excitation and somber, subtly evoked grandeur.

Motherwell

himself is very canny in his intuition of the relative values of these modes,

as they apply to his expressive purposes, and of their limitations as abstract

polarities for a sensibility which is modern both through intellectual act of

faith and through natural inclination. The complexity of his modern aesthetic

is unified by certain basic preferences which govern every period of his work

and are of an almost textbook simplicity: a painting is a sheer extension, not

a window or a door; collage is as much about paper as about form; the impetus

for a painting or drawing starts technically from the subconscious through

automatism (or as he may say "doodling") and proceeds towards the

subject which is the finished work.

These basic

preferences have, however, a superstructure of great variety and subtlety.

Motherwell first showed at Peggy Guggenheim's gallery Art of This Century in

the early '40s. The gallery chooses the artist, but the artist also chooses the

gallery; for better or worse the gallery is the artist's public milieu, and in

this case it was certainly for the better. Art of This Century was the head

quarters in America for the militant surrealists present in New York, and it

also featured importantly Kandinsky, Mondrian, van Doesburg, Helion, as well as

Baziotes, Pollock, Hofmann, Rothko, and Still, among the Americans. Motherwell

thus found himself in a milieu where simultaneous passions for the work of

Mondrian, Max Ernst, de Chirico, Leger and Joseph Cornell were enriching rather

than confusing, joined together in time, place and enthusiasm rather than

compartmentalized and classified as they would have been in most art schools of

the time, if taught at all. As the youngest member of this group, Motherwell

already showed a stubborn individuality and purposefulness which were to remain

characteristic through the years of experimentation with motif and symbol that

lay ahead. In the preface to Motherwell's first exhibition, James Johnson

Sweeney remarked on the artist's thinking ". . . directly in the materials

of his art. With him, a picture grows, not in the head, but on the easel from a

collage, through a series of drawings, to an oil. A sensual interest in

materials comes first." (bibl. 142, page 91)

This sensual

interest in materials has led the artist away from the easel towards the small,

decisively executed paper works of the Lyric Suite series and towards the

monumental canvases, murals really, such as Black on White, Africa, and Dublin

in 1916, with Black and Tan. Motherwell's admiration, which has continued

throughout his career, for Matisse and Picasso, especially the "steady

wide light" of which Edwin Den by wrote, have led him to a clarification

of form and a toughness of drawing and color which would be impossible without

the hard scrutiny of this light. It is important to differentiate the light in

different painters. The distinction is not always historical, nor is it always

about source. It is in its actuality the most spiritual element, technical only

in so far as it requires means, painterly means, to appear at all. It is the

summation of an artist's conviction and an artist's reality, the most revealing

statement of his identity, and its emergence appears through form, color, and

painterly technique as a preconceptual quality rather than an effect.

Motherwell

once mentioned his experience as a child of being thrilled when a teacher drew

in colored chalks a schema of the daily weather—an orange sun with yellow rays

for fair weather, a purple ovoid cloud with blue strokes slanting through it

for rain. Later, he remembered this experience, much as one remembers in

adulthood having been pleased by Blake's Songs of Innocence as a child, only to

find that they are masterpieces even to adults. Perhaps his belief in the

communicative powers of schemata stems from this child hood experience. At any

rate, his sensuality is involved as strongly with schemata as it is with

texture or color. The sexual atmosphere of Two Figures with Cerulean Blue

Stripe (page 52), for example, has a specific tenderness and a poignancy which

has nothing to do with "figure" painting or with handling; it is

dependent on the direct diagrammatic relation in a pictorial sense of the two

forms, where the blue stripe is a curtain drawn away from the intimacy of the

scene. It is the opposite of the Balthus painting of the gnome drawing the

curtain from the nude girl's window—where a surrealist voyeurism gives that

painting piquancy, in the Motherwell a Courbet like health establishes a sense

of both sexuality and repose.

Motherwell

has also, through the same preoccupation with material, been closely involved

with "series" of paintings— in quotes because the series sense is not

necessarily that of subject matter but of sensitivity to findings in the motif

which yield further discoveries in the material. The motif for the Elegies was

discovered while he was decorating a page of a poem by Harold Rosenberg in 1948

(page 76). Almost immediately the motif appears in a Spanish context, related

to Lorca's poetry: At Five in the Afternoon , Granada; and then shifts to the

more specific associations embodied in the "Elegies to the Spanish

Republic." Sometimes the motif itself dictates how to use the medium,

where to drag it, splash it, flatten an intervening area or flow it, in order

to accomplish the presentation of the relationship of the images as a whole experience.

The range of technical procedure between Elegy LVII (page 66) with its almost

expressionistic drama to the strict, flat statement of Elegy LV (page 47)

reveals the fecundity Motherwell has found in this motif and also indicates his

ability to bridge the gap between action painting and what Clement Greenberg

has called the "Post-Painterly Abstractionists." The latter Elegy in

particular is also related to the transcendent exposure of the most recent

works. And always there is an absolute belief in the reality of the schema,

executed with such force that individual paintings of the series have been

variously interpreted as male verticals and female ovoids, as bulls' tails and

testicles hung side by side on the wall of the arena after the fight, and as

purist formal juxtapositions of rectangular and curvilinear forms. As with the

great recent painting Africa , the possibility of the schema's arousing such a

broad range of associations, depending on the emotional vocabulary of the

viewer, is a sign of its power to communi cate human passion in a truly

abstract way, while never losing its specific identity as a pictorial

statement. The exposure is one of sensibility, rather than of literal imagistic

intent, and therefore engages the viewer in its meaning rather than declaring

it. (contd.on page 23)

This is an

extreme divergence in aim from other abstract expressionists, excepting Rothko,

Newman and Gottlieb, while the compulsive urgency and crudity of Motherwell's

drawing in paint separates him even from the latter artists. His work poises

itself on the razor's edge of rawness and elegance, of brutality and

refinement. With this pressure constantly on the hand, the arm, the eye, he

must constantly re-invent the occasion for creation.

As devoted to

exploration of motif as many of his contemporaries, he seems never to have to

avoid repetition— indeed, he seems almost incapable of it. To recognize this

quality in his temperament one need only compare the sensibilities involved in

the Femmes d'Algers variations of Picasso and the "Blast" series of

Gottlieb, for example, with Motherwell's series of "Elegies to the Spanish

Republic." Without making a qualitative judgment, one may say that Picasso

and Gottlieb are able to achieve their visual explorations within the hierarchy

of an important and persuasively established pictorial structure; whereas

Motherwell from At Five in the Afternoon (1949; page 36) on, is fighting an

over-dominant and already clarified symbolic structure from which, through the

years, he will wrench with astonishing energy some of the most powerful,

self-exacerbat ing and brutally ominous works of our time, and some of the most

coldly disdainful ones as well (emptying of Self). In this sense, Motherwell

creates the structure that opposes him, the domination of which he must

overcome to remain an artist— it is not, as with Arshile Gorky, the marvelous

finding of an apparently infinite number of family forms which may be juggled

and tensed for more or less specific narrative purposes. In Motherwell the

family of forms is a relatively small one and the plastic handling of them

carries the burden of intention, whether passionate or subtle, whether buoyant

or subdued; they are never used for narrative purposes, which is perhaps why

Motherwell thinks of Gorky as a surrealist artist (bibl. 38a), so different is

their approach to form. Though both stemmed from the surrealist theory of

automatism, Gorky proceeded into the physiological "innards" of form

and reference, while Motherwell dragged like a beast of prey his automatic

findings into the neutral light of day and of society.

Another

important series, and one which both advances from previous preoccupations with

gesture and proceeds toward later works with calligraphic elements, such as In

Green and Ultramarine (page 49), is the group of works entitled "Beside

the Sea." Here the motif of an abstract wave breaking into the horizon and

charging above it releases a marvelous arm-energy, and the characteristic

Motherwell bands below, rather than becoming indications of landscape, give the

works an emblematic drive. The sea is as much a metaphor as a throw of the dice

is, or the "Spanish Elegies."

Here too, as

elsewhere, beginning with Viva (page 16) and continuing through the "Je

t'aime" series (page 38), many of the works show Motherwell's literal use

of calligraphy as part of the compositional meaning of the painting. In the

case of the "Beside the Sea" pictures, his name is usually scrawled

through one of the dark bands at the bottom to lighten the tone of the passage

and to give variation and variety which balance the sharp force of the

"wave" above. In almost all of Motherwell's work the use of the

signature is compositional: an insistence on identity, to be sure, and also an

indication of the totality of the move away from easel painting— few of the

pictures are "signed" in the traditional sense, they are registered

by the artist as part of his life, in a matter-of-fact pictorial way, rather

coldly. Like de Kooning's, his calligraphy is so beautiful it would be a loss

not to incorporate it in the picture.

Gertrude

Stein gives us, in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, some thoughts which

are particularly applicable to the stance of much of Motherwell's work:

"She always says that americans can understand Spaniards. That they are

the only two western nations that can realize abstraction. That in americans it

expresses itself by disembodiedness, in literature and machinery, in Spain by

ritual so abstract that it does not connect itself with anything but ritual. .

. .

"Americans,

so Gertrude Stein says, are like Spaniards, they are abstract and cruel. They

are not brutal they are cruel. They have no close contact with the earth such

as most europeans have. Their materialism is not the materialism of existence,

of possession, it is the materialism of action and abstraction " This

observation, published in 1933, was prophetic of the whole new movement which

was about to occur in American painting and sculpture, and which indeed had

already been initiated by the three abstract painted metal heads of that year

by David Smith, though she could not have known it. Her insight has also a

relevance to the influence of contemporary Spanish artists, from Picasso and

Gonzalez to Miro, on American and European artists, and particularly to the

difference of application of this influence by the Americans, as opposed to,

let us say, the French and the Dutch, and to the reverberations back on recent

Spanish art. Her own inclination toward automatism was similar to that of many

of the abstract expressionists: it fed and deepened a sense of structural

necessity and of personal identity rather than obscuring the first and

diffusing the latter, as automatism did so often with the surrealists.

Though both

Picasso and Gonzalez as Parisians have had a universal influence stylistically,

their full, bold, and fresh spirit has been most importantly absorbed in

American art, I think, by Motherwell and David Smith, respectively. An

essential caustic Spanish rigor reached these Americans in their different

media, a toughness, a tenacity and wrought-iron insistence which seem to have

been imparted to no one else. For them, the example of identity was stronger

than the style, as the idea of automatism was stronger than the practice.

Instead of inspiration, the example of Picasso gave Motherwell control in his

passion, as that of Gonzalez gave Smith elegance in his ambition, both

necessary qualities for the accomplishment of basically unruly artistic ends. In

contrast to the surrealist painters, Motherwell does not yield to the

subconscious, he is informed by it.

And this

requires the daily confrontation of ethical as well as plastic purposes. There

can be no prefigured beauty to be achieved and no predetermined set of symbolic

referents which have not to be re-examined and tested for validity with each

facing of the canvas. The constant testing and retesting of pictorial meaning,

of the "charge" of imagery, has led to an enormous variety of content

from work to work, and it has also led to the continual replenishment of the

sources of that content, whether one calls it inspiration, inventiveness, restlessness,

painterly ambition, whatever. The kind of artistic anxiety which seems to

characterize Motherwell is the furthest from the kind that is debilitating. It

has led him to find new skills in each period to serve the still mysterious

demands of his consciousness.

FRANK O'HARA

FACE OF THE

NIGHT (FOR OCTAVIA PAZ ) ca. 1977 – 1981

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

182.9 × 457.2

© Dedalus Foundation, Inc./ Licensed by VAGA. New York, NY

RUNNING ELEGY II, YELLOW STATE, 1983

Etching and Aquatint in Colors on George Duchêne

Hawthorne of Larrouque Handmade Paper

Dimensions: 29.8 × 74.9 cm

©The Dedalus Foundation, Inc.

Lithographs

Over his

career Motherwell explored and refined in what he considered an 'endless

challenge' of a serial image which came to be known as the Spanish

Elegy series. From 1948, Motherwell explored this iconic image in drawing,

painting and later in printmaking. His constant search for the perfect

rendition of this form was infinite, explaining:

‘’ My

Elegies … are silent, monumental, more architectonic, a massing of black

against white, those two sublime colors, when used as a color … The reason I've

made so many works … that could be called series … They remain an endless

challenge ‘’ Robert Motherwell

http://nga.gov.au/Motherwell/

ST.

MICHAEL II, 1979

Lithograph,

Screenprint, and Monoprint on White

Arches

Cover Mouldmade Paper

Dimensions: 153 × 101.6 cm

© Dedalus Foundation, Inc./VAGA.

Lithograph

Dimensions:

106.7 × 81.3 cm

© Dedalus Foundation, Inc./VAGA.

UNTITLED

( ELEGY ), 1983-1985

©The Dedalus Foundation, Inc.

ELEGY STUD NO: XIII, 1976

– 1979

©The Dedalus Foundation, Inc.

Collection of David Mirvish

Art © Dedalus Foundation, Inc./Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Photo by Craig Boyko

DANCE I, 1978

Lift-Ground Etching and Aquatint on J.B. Green Paper

Dimensions: 49.5 × 77.5 cm

Edition of 30 + 10AP

©The Dedalus Foundation, Inc.

Art © Dedalus Foundation, Inc./Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Courtesy: Private collection

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 137.1 x 184.5 cm

Elegy to the Spanish Republic, 108 describes

a stately passage of the organic and the geometric, the accidental and the

deliberate. Like other Abstract Expressionists, Motherwell was attracted to the

Surrealist principle of automatism—of methods that escaped the artist's

conscious intention—and his brushwork has an emotional charge, but within an

overall structure of a certain severity. In fact Motherwell saw careful

arrangements of color and form as the heart of abstract art, which, he said,

"is stripped bare of other things in order to intensify it, its rhythms,

spatial intervals, and color structure."

Motherwell intended his Elegies to the Spanish Republic (over 100

paintings, completed between 1948 and 1967) as a "lamentation or funeral

song" after the Spanish Civil War. His recurring motif here is a rough

black oval, repeated in varying sizes and degrees of compression and

distortion. Instead of appearing as holes leading into a deeper space, these

light-absorbent blots stand out against a ground of relatively even,

predominantly white upright rectangles. They have various associations, but

Motherwell himself related them to the display of the dead bull's testicles in

the Spanish bullfighting ring.

Motherwell described the Elegies as his "private insistence that a

terrible death happened that should not be forgot. But," he added,

"the pictures are also general metaphors of the contrast between life and

death, and their interrelation."

Elegy to the Spanish

ELEGY STUD NO: XIII, 1976

– 1979

©The Dedalus Foundation, Inc.

ELEGY TO THE SPANISH REPUBLIC NO.

110C, 1968

Acrylic and Graphite on Paper

15.2 × 20.3 cm

©The Dedalus Foundation, Inc.

Robert Motherwell was only 21 years

old when the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, but its atrocities made an

indelible impression on him, and he later devoted a series of more than 200

paintings to the theme. The tragic proportions of the three-year battle—more

than 700,000 people were killed in combat and it occasioned the first air-raid

bombings of civilians in history—roused many artists to respond. Most

famously, Pablo Picasso created his

monumental 1937 painting Guernica as an expression of outrage

over the events. From Motherwell’s retrospective view, the war became a

metaphor for all injustice. He conceived of his Elegies to the Spanish

Republic as majestic commemorations of human suffering and as

abstract, poetic symbols for the inexorable cycle of life and death.

Motherwell’s allusion to human mortality through a nonreferential visual

language demonstrates his admiration for French Symbolism, an appreciation he

shared with his fellow Abstract Expressionist painters. Motherwell was

particularly inspired by the Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé’s belief that a

poem should not represent some specific entity, idea, or event, but rather the

emotive effect that it produces. The abstract motif common to most of the Elegies—an

alternating pattern of bulbous shapes compressed between columnar forms—may be

read as an indirect, open-ended reference to the experience of loss and the

heroics of stoic resistance. The dialectical nature of life itself is expressed

through the stark juxtaposition of black against white, which reverberates in

the contrasting ovoid and rectilinear slab forms. About the Elegies,

Motherwell said, “After a period of painting them, I discovered Black as one of

my subjects—and with black, the contrasting white, a sense of life and death

which to me is quite Spanish. They are essentially the Spanish black of death

contrasted with the dazzle of a Matisse-like sunlight.” This and other remarks

Motherwell made regarding the evolution of the Elegies indicate

that form preceded iconography. Given that the Elegies date

from an ink sketch made in 1948 to accompany a poem by Harold Rosenberg that

was unrelated to the Spanish Civil War, and that their compositional syntax

became increasingly intense, it seems all the more apparent that the “meaning”

of each work in the series is subjective and evolves over time.

Nancy Spector

Dimensions: 38.4 h x 91.2 w cm

Purchased with the assistance of the Orde Poynton Fund, 2002

© Dedalus Foundation, Inc./VAGA. Licensed by Viscopy

ROBERT MOTHERWELL: AMERICAN / 1915 - 1991

To the Palette for A La Pintura (1969)

Source: Oxford University Press

American painter, printmaker and editor. A major figure of the Abstract

Expressionist generation, in his mature work he encompassed both the expressive

brushwork of action painting and the breadth of

scale and saturated hues of colour field painting, often with a marked emphasis

on European traditions of decorative abstraction.

Motherwell was sent to school in the dry climate of central California to

combat severe asthmatic attacks and developed a love for the broad spaces and

bright colours that later emerged as essential characteristics of his abstract

paintings. His later concern with themes of mortality can likewise be traced to

his frail health as a child. From 1932 he studied literature, psychology and

philosophy at Stanford University, CA, and encountered in the poetry of the

French Symbolists an expression of moods that dispensed with traditional narrative.

He paid tribute to these writers in later paintings such as Mallarmé’s

Swan (1944; Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.) and The Voyage (1949; New

York, MOMA), named after Baudelaire’s poem. As a postgraduate student of

philosophy at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, in 1937–8, he found further

justification for abstraction in writings by John Dewey, Alfred North Whitehead

and David Prall, later relating their views on the expression of individual

identity through immediate experiences to his own urge to reveal his

personality through the gestures of his brushwork (see Action Painting).

Motherwell decided to become an artist after seeing modern French painting

during a trip to Paris in 1938–9, but in order to satisfy his father’s demands

for a secure career he first studied art history from 1940 to 1941 under Meyer

Schapiro at Columbia University, NY. Through Schapiro he met Roberto Matta and

other exiled European artists associated with Surrealism; their use of automatism as a means of registering

subconscious impulses was to have a lasting effect on Motherwell and on other

American painters such as Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner and William Baziotes,

whom he befriended in New York after a trip to Mexico in 1941 with Matta.

While in Mexico, Motherwell executed his first known works, the Mexican

Sketchbook of 11 pen-and-ink drawings in black and white (artist’s col.;

for first page, see Arnason, 1982, p. 29). These were influenced by Matta but

were more abstract and spontaneous in appearance. The appeal of automatist

spontaneity, however, was complemented for him by the clear structure, simple

shapes and broad areas of flat colour in paintings by Piet Mondrian, Picasso

and Matisse.

The interaction of emotionally charged brushwork with severity of structure

began to emerge in paintings such as the Little Spanish

Prison (1941–4; New York, MOMA), a deceptively simple composition of

slightly undulating vertical stripes in yellow and white interrupted by a

single horizontal bar.

In 1943 Motherwell produced a series of dark, menacing works of torn and

paint-stained paper in response to the wartime atmosphere. Surprise and

Inspiration (Venice, Guggenheim), originally called Wounded

Personage, equated the act of tearing with killing and the paint-soaked paper

with bandages. These collages, which heralded his lifelong commitment to the

medium, were presented as the focal point of his first one-man exhibition held

in 1944 at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery, New York.

During the 1940s, like many of his colleagues in the New York School,

Motherwell remained devoted to recognizable imagery, to the expressive

potential of calligraphic marks and to subject-matter of a literary and of a

political nature, as in Pancho Villa, Dead and Alive (gouache and oil

with collage on cardboard, 1943; New York, MOMA). The abstract paintings for

which he is best known, such as Elegy to the Spanish Republic

XXXIV (1953–4; Buffalo, NY, Albright–Knox A.G.), one of a series of more

than 140 large canvases initiated in 1949, expressed a nostalgia that he shared

with many of his generation for the lost cause of the Spanish Civil War. The

works in this series typically consist of black, organic ovals squeezed by

stiff, vertical bars against a white ground, retaining the unpremeditated

quality of an ink sketch even when enlarged to enormous dimensions, as in the much

later Reconciliation Elegy . He conceived of the shapes as elements

within an almost musical rhythm, rich in associations with archetypal imagery

of figures or body parts but sufficiently generalized to convey a mood rather

than a specific representation.

During the

late 1940s and 1950s Motherwell spent much of his time lecturing and teaching;

he taught at Black Mountain College, NC, in 1950, and

from 1951 to 1959 at Hunter College, New York. He also worked on three

influential editorial projects: the Documents of Modern Art series, which he

initiated in 1944 and which included his most important literary contribution

to the history of modern art, The Dada Painters and Poets: An

Anthology (New York, 1951); Possibilities magazine, from 1947;

and Modern Artists in America (New York, 1951), which he co-authored

with Ad Reinhardt.

By the time that he returned fully to his art in the late 1950s, Motherwell had

developed various different series. The Elegies, severe in their

concentration on black and white and in their ever-growing scale, were the

vehicle of his most profound emotions, while the small oil paintings occasioned

by the decay of his second marriage, the Je t’aime series of 1954–8

(e.g. Je t’aime IIA, 1955; New York, Grossman priv. col., see

Sandler, 1970, p. 246), expressed more intimate and private feelings. His

collages, which he began to reproduce also by lithographic means in the 1960s,

began to incorporate material from his studio life, such as cigarette packets

and labels from artists’ supplies, so as to become records of his daily

experiences (e.g. Summer Lights Series published by Gemini GEL in

1973; see Arnason, 1982, pp. 203–6). The coastline near the artists’ colony of

Provincetown, MA, where Motherwell began to spend his summers in 1962, inspired

works such as Beside the Sea No. 5 (1962; artist’s col., see Sandler,

1970, p. 209), a series of 64 pictures in which he splashed oil paint against

rag paper with the full force of his arm as a physical equivalent for the

action of sea spray on the bulkhead in front of his studio.

From 1968 to 1972 Motherwell worked on a series of paintings with the generic

title Open as a personal response to the colour field painting made

by younger abstract painters in the 1960s. Typical of this more contemplative

strain of his art is Open No. 17: In Ultramarine with Charcoal

Line (polymer paint and charcoal on canvas, 1968; artist’s col., see H. Geldzahler: New

York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–1970, New York, 1969, p. 236), which consists

of a surface of a single colour on to which he has drawn three sides of a

rectangle in charcoal lines: an abstract equivalent to the views through open

windows favoured by European painters such as Matisse as metaphors for the

relationship between the interior world of the emotions and the external world

of the senses.

Motherwell’s first important print, the lithograph Poet I (London,

Tate), was published by Tatyana Grossman’s Universal Art Editions in 1961. He

subsequently produced an important body of printed work, notably A la

pintura (1972; London, BM), a limited edition book of 24 unbound pages

printed in letterpress, etching and colour aquatint, in which he exploited the

medium’s capacity for combinations of rich colour and exacting line to

approximate the sensuous effects of his paintings. One of Motherwell’s most

significant, late series of paintings and drawings was the Hollow Men.

While the title of these works is taken from T. S. Eliot’s poem of despair for

Cassius in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Motherwell’s paintings evoke a

different spirit: the artist’s desire to slice through superficiality and

reveal the essence of his art. As such, the Hollow Men incorporates

both the style of the Elegies and that of the Opens. The organic

forms of the Elegies are now translucent rather than solid, and

consequently more exposed; they are set against a threatening black ground. In

these shapes, Motherwell has also revealed more of his automatic drawing, which

he believed was the essence of his artistic personality, than in any

large-scale works since the 1950s. The Hollow Men stands as one of

Motherwell’s final attempts to assert the authenticity of his Abstract

Expressionist art.

Robert Saltonstall Mattison

From Grove Art Online

You may visit

to see more Paintings and information from my latest news of Robert Motherwell’

s exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim Collection to click below link.

http://mymagicalattic.blogspot.com/2013/06/peggy-guggenheim-collection-robert.html

1961.jpg)

%2C%2Bca.%2B1977%2B-1981.JPG)

%2B1975.jpg)

%2B1979-80.jpg)

%2C%2B1971.jpg)

%2C%2B1941.PNG)

%2C%2B1977.jpg)

%2C%2B1944.jpg)