THE TATE COLLECTION I: PASSION OF ARTS

THE IMAGE & IMAGINATION OF THE

FOURTH DIMENSIONS IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART AND CULTURE

LINDA DALRYMPLE HENDERSON UNIVERSITY OF

TEXAS AT AUSTIN

ABSTRACT

‘’ One of the most important

stimuli for the imaginations of modern artists in the twentieth century was the

concept of a higher, unseen fourth dimension of space. An outgrowth of the

n-dimensional geom[1]etries developed in the nineteenth century, the concept

predated the definition of time as the fourth dimension by Minkowski and

Einstein in relativity theory. Only the popularization of relativity theory

after 1919 brought an end to the widespread public fascination with the

supra-sensible fourth dimension between the 1880s and 1920s. Ini[1]tially

popularized by figures such as E. A. Abbott, Charles Howard Hin[1]ton, Claude

Bragdon, and P. D. Ouspensky (as well as science-fiction writers), the fourth

dimension was a multivalent term with associa[1]tions ranging from science,

including X-rays and the ether of space, to idealist philosophy and mystical

“cosmic consciousness.” This essay focuses on the differing approaches to

higher spatial dimensions in the cubism of Pablo Picasso and Juan Gris, the

suprematism of Ka[1]zimir Malevich, and The Large Glass project of Marcel

Duchamp in the early twentieth century. It concludes by examining contemporary

artist Tony Robbin’s thirty-year engagement with the mathematics of

four-dimensional geometry and computer graphics, as well as his cur[1]rent work

with knot theorist Scott Carter ‘’

In the wake of a short article on the

four-dimensional hypercube titled “Visualizing Hyperspace,” published in the

March 1939 issue f Scientific American, the journal’s editors found it

necessary to re[1]spond in September 1939:

‘’ From time to time . . . the editors

have received inquiries from puzzled readers who appear to be confused about a

variety of questions suggested by this ar[1]ticle. Is not time the fourth

dimension? How do mathematicians know that there are more than the three

dimensions with which we are all daily familiar? . . . First, regarding time as

the fourth dimension: True, time does figure in the so-called “space-time

continuum,” but not as an extra dimension of space. Next, how do they know

there are extra dimensions of space? They don’t! They play with them, however,

just as if they did exist. . . . The mathematician is a whimsical fellow who

deliberately enjoys creating a make-believe and then proceeding to show what

would be the case if it were true. . . . What probably confuses the puzzled

non-mathematician is the fact that the mathematician uses for his excursions

into the imaginary the same word he uses in connection with something he and

all the rest of us know to exist; that is, “dimensions.” If he would call them

something else the confusion would promptly end for most of us.1’’

The critical role of the imagination in

mathematics and geom[1]etry has long been acknowledged and given more serious

discussion than in this description of mathematicians as “whimsical fellow[s].”

In the twentieth century, popular books such as Edward Kasner and James

Newman’s Mathematics and the Imagination of 1940 and David Hilbert and S.

Cohn-Vossen’s Geometry and the Imagination of 1952 have made that connection

apparent for the lay public. Hilbert em[1]phasized the importance of a

specifically visual component of the imagination, declaring in his

introduction: “With the aid of visual imagination, we can illuminate the

manifold facts and problems of geometry, and beyond this, it is possible in

many cases to depict the geometric outline of the methods of investigation and

proof.”2 The beautiful drawings in Hilbert’s books certainly stimulated the

creative imaginations of a number of artists who used the book, in[1]cluding

sculptor Mark di Suvero and members of the Park Place Gal[1]lery, who responded

to his sections on topology and “Polyhedra in Three and Four Dimensions.”3 In a

similar way, H. S. M. Coxeter’s 1963 book, Regular Polytopes, served as a vital

inspiration for painter Tony Robbin as he began to explore four-dimensional

geometry dur[1]ing the early 1970s. Coxeter, noting that while “we can never

fully comprehend” figures in four or more dimensions,” had declared: “In

attempting to do so, however, we seem to peep through a chink in the wall of

our physical limitations, into a new world of dazzling beauty.”4

Indeed, it was not simply geometry, but

specifically the nine[1]teenth-century field of n-dimensional geometry and the

concept of a possible fourth spatial dimension that emerged from it in the

1870s that proved crucial to the imaginations of twentieth-century artists.

From the 1880s to the 1920s, popular fascination with an invisible, higher

dimension of space—of which our familiar world might be only a section or

shadow—is readily apparent in the vast number of articles and the books such as

architect Claude Bragdon’s A Primer of Higher Space (The Fourth Dimension)

(1913) published on the topic.5 Two plates from Bragdon’s book are useful in

setting forth two of the basic ways of conceptualizing a higher spatial

dimension: the gener[1]ation of the next higher-dimensional form by motion

through space (fig. 1), and sectioning or slicing (fig. 2). In both approaches,

reason[1]ing by analogy to the relationship of two to three dimensions is

cen[1]tral to imagining the transition from three to four dimension

Just as Bragdon’s beautiful

hand-lettered plates provide a time capsule of approaches to the fourth

dimension in 1913, the 1910 book, The Fourth Dimension Simply Explained,

collected the win[1]ning essays in a 1909 contest sponsored by Scientific

American on the topic, “What Is the Fourth Dimension?” 6 Virtually all of the

Scientific American essayists in 1909 treated the fourth dimension as a spatial

phenomenon, because the widespread popularization of Einstein’s special and

general theories of relativity (1905, 1916) would begin only in 1919 with the

solar eclipse that established em pirically the curvature of light that

Einstein’s theory had predicted.7 It was little wonder, then, that in 1939,

Scientific American readers were confused, since during the course of the

1920s, Einstein and mathematician Hermann Minkowski’s earlier incorporation of

time into the four-dimensional space-time continuum had gradually overshadowed

cultural memories of the geometrical, spatial fourth dimension. During the

1930s through the 1950s, in fact, the fourth dimension of space essentially

went underground, staying alive in nonmathematical culture primarily in

science-fiction writing and in the mystical, philosophical literature that had

developed around the idea.8

Mathematicians, of course, continued to

study four-dimensional geometry, but even Kasner and Newman recognized the need

to explain the idea to a 1940s audience in a chapter of Mathemat[1]ics and the

Imagination on “Assorted Geometries—Plane and Fancy.” “Physicists may consider

time to be the fourth dimension, but not the mathematician,” they assert at the

start of their explication of the con[1]cept. While their discussion focuses on

the geometrical properties of four-dimensional objects and the analogies by

which we can reason about them, their conclusion takes the idea well beyond the

realm of geometry to point out its larger significance in the history of

hu[1]man thought: “No concept that has come out of our heads or pens marked a

greater forward step in our thinking, no idea of religion, philosophy, or

science broke more sharply with tradition and com[1]monly accepted knowledge,

than the idea of a fourth dimension.”9[1]

From its first popularization in

English theologian E. A. Abbott’s Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by a

Square of 1884, the fourth dimension had been linked to the enlarging or

freeing of thought and imagination. Abbott dedicated his cautionary tale about

a two-dimensional world oblivious of the larger three-dimensional space in

which it existed “To the Inhabitants of Space IN GENERAL,” whom he hoped would

“aspire yet higher and higher To the secrets of FOUR FIVE OR EVEN Six

Dimensions Thereby contributing To the Enlargement of THE IMAGINATION.”10 This

theme would be come a leitmotif of literature on the fourth dimension both in

the context of mathematics and as it quickly acquired broader philo[1]sophical

implications. As Casius Keyser wrote in a 1906 essay in The Monist titled

“Mathematical Emancipations”: “The hyper-dimen[1]sional worlds that man’s

reason has already created, his imagination may yet be able to depict and

illuminate. . . . It is by creation of hyperspaces that the rational spirit

secures release from limitation. In them it lives ever joyously, sustained by

an unfailing sense of in[1]finite freedom.”11 Citing Keyser, H. P. Manning, in

his 1914 textbook Geometry of Four Dimensions, argued that the “synthetic”

study of the “forms and properties” of four-dimensional figures so “that it is

almost as if we could see them” results in “greatly increas[ing] our power of

intuition and our imagination.”12

he figure who definitively extended the

fourth dimension be[1]yond its mathematical roots, while maintaining its

geometrical core meaning, was the Englishman Charles Howard Hinton. In his

books A New Era of Thought (1888) and The Fourth Dimension (1904), Hin[1]ton

developed the philosophical implications of four-dimensional space and secured

its place in late nineteenth- and early twentieth[1]century culture. Hinton’s

“hyperspace philosophy” was an idealist worldview based on his belief that by

developing an intuitive appre[1]hension of four-dimensional space, individuals

would gain access to true reality and hence resolve the problems of the

materialist three[1]dimensional world. According to Hinton,

‘’ w]hen the faculty is acquired—or

rather when it is brought into conscious[1]ness, for it exists in everyone in

imperfect form—a new horizon opens. The mind acquires a development of power,

and in this use of ampler space as a mode of thought, a path is opened by using

that very truth which, when first stated by Kant, seemed to close the mind

within such fast limits. . . . But space is not limited as we first think.13 ‘’

Hinton’s method for “educating the

space sense” of his readers was a set of exercises to be carried out with a

block of multicolored cubes, such as those pictured in various colors on the

frontispiece of The Fourth Dimension (fig. 3). By memorizing the relative

positions and color gradations of cubes within large blocks, Hinton’s readers

were to develop their mental powers and transcend self-oriented per[1]ception

(e.g., the senses of left/right and up/down or gravity).14 With this knowledge,

they would also be able to visualize the passage of the successive cubic sections

of a four-dimensional hypercube through three-dimensional space. But this

training was simply the practical prelude to what Hinton hoped would be “a new

era of thought,” as he declared in that book of 1888: “I shall bring forward a

complete system of four-dimensional thought—mechanics, science, art. The

necessary condition is, that the mind acquire the power of using

four-dimensional space as it now does three-dimensional.” Although Hinton never

realized such a “system,” he extended his ideas into the realm of literature,

writing a series of “scientific romances” pub[1]lished in 1884–1885 and 1896.15

Although Hinton achieved little

personal success or recognition in his lifetime, his writings—with their

message of a higher truth and the possibility of self-realization—were

remarkably influential in the United States and Europe as well as in England.

The Fourth Dimen[1]sion, for example, was reprinted in London five times, in

1906, 1912, 1921, 1934, and 1951. Those who subsequently built upon and/or promulgated

his ideas included Bragdon in the United States, math[1]ematician and mystic

Peter Demianovich Ouspensky in Russia, Ger[1]man theosophist/anthroposophist

Rudolf Steiner in Germany, both mathematicians E. Jouffret and Maurice Boucher

and theosophists in France, the symbolist writer Maurice Maeterlinck in

Belgium, and theosophist C. W. Leadbeater in England.16 Ouspensky developed a

mystical interpretation of the fourth dimension, associating it with infinity

and the achievement of “cosmic consciousness” of a truer, four-dimensional

reality.17 If Ouspensky was envisioning a liberating effect quite different

from Hinton’s more pragmatic approach, the theme of the fourth dimension as a

liberating agent of some kind ran through most all of its interpretations. As

Bertrand Russell wrote in his review of The Fourth Dimension in Mind in October

1904:

‘’ The merit of speculations on the

fourth dimension—a merit which the present work possesses in full measure—is

chiefly that they stimulate the imagination, and free the intellect from the

shackles of the actual. A complete intellectual liberty would only be attained

by a mind which could think as easily of the non-existent as of the existent.18

‘’

Writers such as Hinton and Bragdon, in

particular, had a major impact on the way the public imagined and imaged the

fourth di[1]mension during the twentieth century. Painters were particularly

responsive to the idea, and many of the stylistic innovations in the first

decades of the century were made in the context of attempts to represent or

signify in some way the elusive fourth dimension. Russell’s reference to the

“shackles of the actual” is especially tell[1]ing, because it points up the

fundamental shift that the possibil[1]ity of a spatial fourth dimension

produced in the visual arts. For artists, whose visual imaginations had been

largely constrained by painting’s traditional allegiance to the visible world,

the possibil[1]ity that space was actually four-dimensional was revolutionary.

The chiaroscuro modeling techniques and one-point linear perspective painters

had relied upon since the Renaissance to create convinc[1]ing three-dimensional

form and space were irrelevant if the world had four dimensions. One of the

pioneers of totally abstract art, the Russian suprematist painter Kazimir

Malevich, was encouraged by his belief in four-dimensional space to leave

behind completely all traces of the visible world, as discussed below.

There was another strong impetus for

breaking the “shackles of the actual” in the late nineteenth- and early

twentieth centuries: the discovery of the X-ray by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895.

X-rays proved definitively the limited nature of human vision, which perceives

only the narrow band of visible light in the electromagnetic spec[1]trum then

being identified.19 With an impact second only to that of the atomic bomb, the

discovery of the X-ray undoubtedly con[1]tributed to the continued popular

interest in the fourth dimension, which might otherwise have remained the

province of mathemati[1]cians, philosophers, and mystics.20 Once the X-ray

established the inadequacy of the human eye, however, who could deny with

cer[1]tainty the possibility of a fourth spatial dimension simply because it

was invisible?

In addition to the fourth dimension and

the X-ray, the successive discoveries during the 1890s of the electron and of

radioactivity, as well as the interest in the Hertzian waves of wireless

telegraphy, con[1]tributed further to a radical reconception of the nature of

matter and space in this period. 21 Beyond its possible four-dimensionality,

matter was transparent to the X-ray and, on the model of radioac[1]tivity, was

often discussed as dematerializing into the space around it. Moreover, during

this period, that space was never thought of as empty; instead, it was

understood to be filled with the impalpable ether of space traversed by various

ranges of vibrating waves, and the ether itself was thought by some to be the

source of matter, as in the “electric theory of matter.”22 Widely popularized,

these new scientific discoveries, along with the possibility of a fourth

spatial dimension, strongly suggested that an invisible reality existed just

beyond the reach of human perception. And in the view of artists and critics,

it was the sensitive artist possessed of intuition and imagination—the

successor to the visionary seer posited by the symbolists during the 1890s—who

would be required to evoke higher dimensions, as well as the newly fluid

conceptions of matter and space.

This essay samples the techniques

employed in three of the major artistic responses to the fourth dimension

during the early twentieth century: cubism, suprematist abstraction, and the

art of Marcel Du[1]champ, the early twentieth-century artist who engaged the

fourth dimension most fully, albeit playfully. Only toward the end of the

twentieth century would the advent of computer graphics make it possible for

artists and geometers to navigate four-dimensional space with mathematical

tools, but here also, artistic intuition and imagi[1]nation would play an

important role. After briefly surveying the cul[1]tural understanding of the

term “fourth dimension” at mid-century, when Einsteinian space-time dominated

the layman’s awareness of the concept, the essay concludes with a look at the

computer-era work of artist Tony Robbin, as well as his collaboration with

math[1]ematician Scott Carter to explore the visual properties of braided

surfaces and lattices in four and five dimensions.

CUBISM: WINDOWS ON INVISIBLE

GEOMETRICAL COMPLEXITY

The cubist painter and theorist Jean

Metzinger was the first artist to write about the importance of the new

geometries for contempo[1]rary painters, and he and Juan Gris are said to have

studied four-di[1]mensional geometry with the insurance actuary Maurice

Princet.23 All three of these figures were close to Pablo Picasso, who in 1909,

along with Georges Braque, developed the style that has come to be known as

analytical cubism. While Picasso and Braque drew critical lessons from the art

of Paul Cézanne and the conceptual nature of African sculpture, their mature

cubism—with its faceted forms and fusion of figure and ground—was a response as

well to the exhilarating new ideas about reality issuing from popularized

science and mathemat[1]ics.24 If Picasso described his goal in cubism as

“paint[ing] objects as I think them, not as I see them,” the more theoretically

oriented Metzinger and the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, another of Picasso’s

friends, touted the fourth dimension overtly to justify the cubist painter’s

freedom both to deform objects and to reject perspective. “It is to the fourth

dimension alone that we owe a new norm of the perfect,” Apollinaire declared in

1912, adding that the concept was part of the “language of the modern

studios.”25 In his book Les Pein[1]tre Cubistes of 1913, the poet likewise

dismissed perspective as “that miserable tricky perspective, that fourth

dimension in reverse.”26

In the early 1970s, I suggested that

plates from Esprit Pascal Jouf[1]fret’s 1903 book Traité élémentaire de

géométrie à quatrième dimensions, such as that shown in figure 4, would have

confirmed Picasso’s stylistic direction.27 Since that time, more discussion of

Jouffret, Prin and Picasso has occurred, and Tony Robbin in his book Shadows of

Reality: The Fourth Dimension in Relativity, Cubism, and Modern Thought argues

convincingly that certain techniques in Picasso’s paintings of this period, especially

his 1910 Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (Art Institute of Chicago), derive

directly from Jouffret’s innovative drawing techniques.28 Robbin is

particularly interested in the complex, rectangular areas in the head of

Kahnweiler, which he compares to several other of Jouffret’s illustrations.

“The odd way in which spaces are both inside and outside a four-dimensional

fig[1]ure [with its three-dimensional bounding cells] is the subject of both

Jouffret’s illustration and Picasso’s portrait of Kahnweiler,” Robbin

concludes.29

For the purposes of this essay, figure

4 serves effectively to point up the general similarity between cubist

paintings, including Gris’s Still Life Before an Open Window: Place Ravignan

(fig. 5) and Jouffret’s techniques for presenting complex figures. Here, the

geometer’s use of transparency, shifting overlays of differing views of an

object, and the resulting spatial ambiguity are strikingly similar to Gris’s

approach. Like other cubists, Gris combines multiple viewpoints, just as Henri

Poincaré had suggested in his 1902 book La Science et l’hypothèse that a

four-dimensional object could be rendered by means of “several perspectives

from several points of view.” Given the “muscular sensations” accompanying the

transition from view to view, Poincaré had concluded: “In this sense we may say

the fourth dimension is imaginable.”30 While Gris’s view of trees and a

building out the window may appear conventional enough (it is actually a

distinct blue monochrome), the complex overlay of visual signs on the

table—interacting with the wrought iron of the bal[1]cony—deny completely the

possibility of reading the space or mat[1]ter as three-dimensional.

In addition, Still Life Before an Open

Window effectively evokes the newest scientific ideas of matter and wave-filled

space. Here, the interior and exterior of objects and of the room itself

interpenetrate, producing the kind of clairvoyant, see-through vision of

three-di[1]mensional forms that would be accessible to four-dimensional sight

or an X-ray. Not only are spatial clues ambiguous, but Gris plays one kind of

light off another, drawing on both visible and invisible light. The mauve and

green palette in the central area of the still life contrasts markedly with the

ultraviolet or “black light” that seems to illuminate the blue/black areas

around the center. Although the bright, seemingly natural light in the central

area does not cast shadows or give substance to the objects of the still life,

it does re[1]fract and distort the Le Journal banner line dramatically. Only

the curtained window in the upper left corner is painted convention[1]ally in

light and shade. However, it is dwarfed by the other ranges of light in the

painting, which thus makes a powerful commentary on the changed status of the

window as source of visible light and, metaphorically, truth. Gris’s Still Life

and other cubist paintings are testaments to the new paradigm of reality

ushered in by the discov[1]ery of X-rays and interest in the fourth dimension.

Such paintings are new kinds of “windows”—in this case, into a complex,

invisible reality or higher dimensional world as imagined by the artist.

My 1983 book The Fourth Dimension and

Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art was written before I had studied the

late-Victorian ether physics still prevalent during the early twentieth

century. In the 1980s—and actually from the 1940s onward—the science with which

cubism was associated in art historical literature was Ein[1]steinian

relativity theory. That conflation was the result of a kind of “short circuit”

in the 1940s when discussions of cubist references to the fourth dimension were

erroneously linked to the only fourth dimension the public knew—namely, the

space-time world of Ein[1]stein.31 But such debates over the supposed

relationship of Picasso to Einstein also served to occlude study of the science

to which Picasso, Gris, and others were responding in pre–World War I Paris.

The re[1]covery of that science has been critical to a fuller history of the

im[1]pact of the spatial fourth dimension, because the concept was rarely

understood in isolation from contemporary ideas about space and matter;

instead, it was regularly discussed against the backdrop of contemporary ether

physics, beginning with Hinton, who focused attention on the fourth dimension’s

possible relation to the ether itself.32

A case in point is the 1903 book by

Maurice Boucher, Essai sur l’hyperespace: Le Temps, la matière et l’énergie,

which Metzinger mentions in his memoirs. There, Boucher argues in support of

the fourth dimension: “Our senses, on the whole, give us only deformed

im[1]ages of real phenomena, some of which have long remained un[1]known,

because none of our organs put us in direct contact with them.”33 As we shall

see, the Russian avant-garde knew Boucher’s book, as did, quite certainly,

Duchamp. Such a text makes clear the close connections of interpretations of

the fourth dimension to a contemporary science that, while it dealt with

invisible phenom[1]ena like the X-ray and the ether, was highly suggestive to

the visual imaginations of artists.

Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism:

Sections Afloat in Infinite Space If the cubists created geometrically complex

images that suggested the invisible reality beyond surface appearances, the

abstract supre[1]matism of Kazimir Malevich utilized the method of sectioning

to create geometrical planes moving in space.34 The two-dimensional analogy

that lay behind Flatland and was illustrated in Bragdon’s Primer of Higher

Space (fig. 2) had first been discussed extensively by Hinton, and both

Ouspensky—Hinton’s Russian disciple—and Boucher in his Essai sur l’hyperespace

followed Hinton’s model. That Malevich and his friend, musician and artist

Mikhail Matyushin, knew Boucher’s Essai, with its unification of the fourth

dimension and ether physics, is clear from a 1916 text by Matyushin in which he

writes: “How to solve the question of ‘space,’ ‘where’ and ‘where to’?

Lobachevsky, Riemann, Poincaré, Bouché, Hinton and Mink[1]ovsky provided the

answer.”35 In addition to Boucher, Poincaré, Hinton, and Minkowski, Matyushin

here cites the two major pio[1]neers of non-Euclidean geometries, Nikolai

Ivanovich Lobachevsky and Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann.

Matyushin, however, does not include in

this list the figure who was even more central to Malevich’s invention of

suprematism: Ous[1]pensky, the primary Russian advocate of the fourth

dimension. By 1916, in fact, Malevich’s and Matyushin’s enthusiasm for

Ouspensky had cooled somewhat, since, in the 1914 edition of his 1911 Tertium

Organum, Ouspensky had criticized contemporary Russian artists for what he

considered their wrong-headed approach to the fourth di[1]mension. Nonetheless,

Ouspensky’s books, The Fourth Dimension of 1909 and Tertium Organum: A Key to

the Enigmas of the World of 1911, which provided a full accounting of Hinton’s

ideas, were criti[1]cal sources for Malevich and his colleagues Matyushin and

the poet Alexei Kruchenykh.36 Most important for Malevich’s mature

supre[1]matism, however, was Ouspensky’s discussion of the transition to

four-dimensional “cosmic consciousness” and its relation to infinity. Indeed,

Boucher’s chapter on infinity and the fourth dimension, as well as his

dismissal of the visible world of the senses as illusion, may have been a stimulus

for Ouspensky himself—as well as for Malevich.

When Malevich exhibited his first

suprematist canvases at the 0.10 exhibition in St. Petersburg in December 1915,

one canvas was titled Movement of Painterly Masses in the Fourth Dimension, and

oth[1]ers bore the subtitles Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension and Color

Masses in the Second Dimension (fig. 6). Malevich’s suprematist paint[1]ings

with planes of one color only strongly suggest the two-dimen[1]sional sections

or traces created when three-dimensional objects pass through a plane, as

discussed in Hinton and Ouspensky and illustrated in Bragdon’s Primer of Higher

Space. These “color masses in the second dimension” may have served Malevich as

indirect signs of the fourth dimension by means of the well-known

two-dimensional analogy.

Malevich’s Painterly Realism of a

Football Player: Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension (fig. 7), however, is

more typical of his suprema[1]tist works, which generally include multicolored

overlapping planes that prevent a reading of the image as two-dimensional.

Here, the artist evokes higher dimensions more directly by suggesting motion

through an infinite, multidimensional white space. Eschewing

three[1]dimensional form, Malevich sets two-dimensional planes of high[1]keyed

color into motion, drawing on the theme of time and motion as provisional means

of gaining higher spatial understanding. Both Hinton and Ouspensky understood

time as a means toward a spatial end, as in its role in both the generation of

high-dimensional forms (fig. 1) and their sectioning (fig. 2).37 Undoubtedly

reflecting ideas he shared with Malevich, Matyushin wrote in his diary in May

1915: “Only in motion does vastness reside. . . . When at last we shall rush

rapidly past objectness we shall probably see the totality of the whole

world.”38

According to Ouspensky, a “sensation of

infinity” and vastness would characterize the first moments of the transition

to the new “cosmic consciousness” of four-dimensionality, and Malevich

re[1]ferred specifically to the space of his suprematist paintings as the

“white, free chasm, infinity.”39 Fascinated by flight, Malevich does not,

however, paint his space blue; instead, it is a cosmic white ex panse in which

variously colored elements float freely, without any specific left/right or

up/down orientation, just as Hinton had argued that gaining independence from

conventional orientation and the pull of gravity would be the initial step in

educating one’s “space sense” to perceive the fourth dimension. Like a cubist

painter, Malevich generally avoided any signs of the third dimension. However,

in contrast to cubism’s geometrical complexity and suggestion of a window onto

an invisible world, Malevich sought to convey the physiological experience of

four-dimensional cosmic consciousness, relying on concepts long associated with

the fourth dimension: spatial vastness and infinity, freedom from gravity and

specific ori[1]entation, and implied motion.

MARCEL DUCHAMP: PLAYFUL GEOMETRY AND

OTHER SIGNS OF THE FOURTH DIMENSION

Marcel Duchamp, who had begun his

painting career in the con[1]text of cubism, was dedicated to realizing aspects

of four-dimen[1]sional space in his art, but both his approach and his result

were far removed from cubism and from Malevich’s suprematism. Du[1]champ’s

nine-foot-tall work on glass, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even

(1915–1923), known as The Large Glass (fig. 8), is a mathematical/scientific

allegory of sexual quest, in which Duchamp worked to create an unbridgeable gap

between the four-dimensional realm of the biomechanical Bride above and the

three-dimensional Bachelor Machine below.40 His sources on the fourth dimension

in[1]cluded Matyushin’s entire list of names, quoted earlier, with the

sub[1]stitution of Jouffret for “Minkovsky.” But he also read many other

sources, since he actually gave up painting for a time and took a job at the

Bibliothèque Ste. Genèviève in 1912, determined as he was to “put painting at

the service of the mind.”41 Disgusted by what he be[1]lieved was the mindless,

“retinal” painting of his fellow artists, Du[1]champ found in the fourth

dimension a topic tied closely to mental activity, including imagination,

intuition, and reason (the latter a prominent theme in Boucher’s book), and

thus a field in which he could define himself as a new kind of artist. Not only

did he trade canvas and oil paint for glass and unconventional materials, such

as lead wire, lead foil, and dust, but he developed the Large Glass as a

text/image project, writing hundreds of preparatory notes that he considered to

be as important as the object itself.4

Without Duchamp’s notes, we would be

hard pressed to decipher the basic narrative of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her

Bachelors, Even, as well as to appreciate the “playful physics” and geometry

that un[1]derlie it. Basically, a series of operations begins at the left side

of the Bachelors’ realm during which “illuminating gas” is gradually

lique[1]fied into a semen-like “erotic liquid,” which is ultimately splashed

onto the upper half to form the chance-determined “Nine Shots” at the right of

the Bride’s realm. This is the closest the Bachelors come to making contact

with the object of their desire. In order to establish insurmountable

allegorical “collisions” between the desiring Bach[1]elors and the unreachable

Bride, Duchamp drew on contemporary science as well as the

four-to-three-dimensional contrast between their realms.43 Boucher’s Essai sur

l’hyperespace would have been an es[1]pecially relevant source for him, since

it treated the fourth dimension in relation to contemporary ideas on matter,

energy, and the ether. In fact, wave-borne communication is a central theme of

the Large Glass, in which the Bride, hanging gravity-free in her etherial,

four[1]dimensional realm, issues commands to the Bachelors by means of her

“splendid vibrations.” The Bride’s basic columnar form is rooted in X-ray

images, and her vibratory communications are based on the latest wireless

telegraphy and radio control via the ether. By con[1]trast, the laws of

classical mechanics, playfully “stretched” by Duch[1]amp, rule the lower half

of the work, where the Bachelors are further constrained by perspective and the

relentless pull of gravity.44

Although Duchamp never published the

comprehensive text he originally envisioned to accompany the Large Glass, his

boxes of facsimiles of his notes, primarily The Green Box of 1934 and A

l’infinitif (The White Box) of 1966, testify to the breadth of his study and

his powers of verbal invention in creating his “hilarious pic[1]ture.”45 Given

the fate of the spatial fourth dimension in the wake of Einstein’s emergence in

the 1920s, Duchamp chose not to in[1]clude his notes on the fourth dimension in

the Green Box. But by the 1960s, the subject was beginning to reemerge in

culture, and his White Box notes on the subject display his rich imagination

and wit as he played with the laws of four-dimensional geometry and ex[1]plored

other means by which he might make the Bride’s realm four[1]dimensional.

Duchamp’s notes and drawings offer highly inven[1]tive approaches to the topic,

which, in the end, were unrealizable; nonetheless, his verbal invention in the

notes stands as a significant counterpart to the Large Glass itself

Duchamp speculated extensively on

four-dimensional geometry, working by means of analogy and developing his own

playful laws n the subject.46 Although he considered Poincaré’s ideas on

geo[1]metrical continua and cuts as well as the use of mirrors and virtual

images as possible signs of the Bride’s four-dimensionality, he finally

returned to the notion of shadows, as articulated by Jouffret: “The shadow cast

by a 4-dim’l figure on our space is a 3-dim’l shadow.”47 Thus Duchamp painted

the Bride to resemble a photograph of a three-dimensional figure, whom he

thought of as the shadow of the true, four-dimensional Bride. However, he also

took additional steps to augment the Bride’s four-dimensional otherness,

creating for her a spatial realm he defined as beyond measure (in contrast to

the Bachelor’s “mensurable” and “imperfect” forms).48 In her in[1]finite,

immeasurable realm, the Bride, described as free of gravity, suggests qualities

associated with expanded spatial perception in the tradition of Hinton. Yet

Duchamp was far from Ouspensky’s and Malevich’s pursuit of mystical “cosmic

consciousness”; instead, the self-proclaimed Cartesian was much closer to

Boucher, the advocate of reason, in approaching the fourth dimension.4

Duchamp abandoned the execution of the

Large Glass in 1923, leaving it unfinished and missing several components.

Although he never added the Juggler or Handler of Gravity to the work itself,

this key intermediary figure was to have stood symmetrically oppo[1]site the

Bride, and to have facilitated communication between the Bride and the

Bachelors.50 Drawn in the form of a spiral, the Juggler would have been able to

function in both three and four dimen[1]sions, thus evoking the

dimension-transcending associations of the spiral, which Hinton had utilized to

demonstrate the illusion of a circling point created as a spiral passed through

a plane.51 The spiral had a second link to the fourth dimension: advocates of a

higher dimension pointed to right- and left-handed spiral growth in nature as

“scientific” evidence for the existence of four-dimensional space. Such mirror

symmetrical pairs, which also included right and left hands and right- and

left-handed growing crystals as well as spirals, would need to be turned through

a fourth dimension to be made to coincide with their opposites. Mirrors

themselves were also preva[1]lent in popular literature on the fourth dimension

from the start, in[1]cluding the mathematician Lewis Carroll’s Through the

Looking Glass of 1872.52 Duchamp utilized mirror silver on the surface of the

Large Glass to create the “Oculist Witnesses” (the circular eye chart–like

forms at the right of the Bachelors’ realm), who were to “dazzle” up[1]ward a

mirror reflection of the orgasmic splash to produce the Nine Shots. He had

already played with the notion of mirror reversals and hinges in his hinged,

semi-circular glass panel Glider Containing a Watermill of 1913 (Philadelphia

Museum of Art), which offers the viewer mirror-reversed images of its front and

back.

During the 1920s and ’30s, Duchamp

combined his interest in the spiral with movement, setting spiraling disks into

motion so that they seemed to pulsate outward and inward. These experiments in

optics would subsequently link Duchamp, the early twentieth century’s most

committed student of the spatial fourth dimension, to the kinetic art that

developed during the early 1920s in response to the new focus on time in

Einsteinian relativity theory. The Hun[1]garian artist László Moholy-Nagy was

the primary advocate of the new space-time kinetic art, which he promulgated in

books such as his Von Material zu Architektur (subsequently translated as The

New Vision) of 1928 and Vision in Motion of 1947.53 By the later 1940s and

’50s, Duchamp was regularly grouped with Moholy-Nagy and Alexander Calder as a

kinetic artist. Yet he had not forgotten the spatial fourth dimension that had

been so central to the Large Glass, and in 1957, the artist and his wife Teeny

were reading Kasner and Newman’s Mathematics and the Imagination, which was in

its four[1]teenth edition.54 Duchamp must have been delighted by the au thors’

praise for the spatial fourth dimension (no “greater forward step”), as quoted

earlier. And with stirrings of renewed interest in the idea during the later

1950s and ’60s, including in Martin Gard[1]ner’s Scientific American columns,

Duchamp clearly decided that his playful musings on four-dimensional geometry

might once again be intelligible and decided to publish them.55

Science fiction was one of the contexts

in which the spatial fourth dimension had survived, and, recast as the “fifth

dimension” (because time was now so widely linked to the fourth dimension), the

idea achieved new exposure in fantasy literature (e.g., Madeleine L’Engle’s

1962 A Wrinkle in Time) and on television, beginning in 1959, in The Twilight

Zone. There, Rod Serling’s memorable introduction touched upon many qualities

earlier associated with the fourth dimension, in[1]cluding imagination. “There

is a fifth dimension,” he intoned

‘’ beyond that which is known to man.

It is a dimension as vast as space and as timeless as infinity. It is the

middle ground between light and shadow, be[1]tween science and superstition,

and it lies between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge. It

is the dimension of imagination. It is an area which we call . . . the Twilight

Zone.56 ‘’

In his 1962 Profiles of the Future,

Arthur Clarke recalled of the idea: “The fourth dimension has been out of

fashion for quite a while: it was fashionable round the turn of the century,

and perhaps it may come back into style some day.”57 That would certainly begin

to happen subsequently during the 1960s, in the “space age” Clarke himself had

foretold in his writings.

F or those artists who turned their

attention to the spatial fourth dimension during the second half of the

twentieth century, it was often an encounter with literature on the subject

from the early years of the century that introduced them to the concept. This

was true for Park Place Gallery artist Peter Forakis, who in 1957, while a

student at the California School of Fine Arts, found copies of Bragdon’s Frozen

Fountain of 1932 and Ouspensky’s Tertium Organum at an artist’s estate sale. In

the age of Einstein, these books were akin to some kind of ancient wisdom that

went against the grain of culture at large. During the 1960s, Forakis would go

on to explore approaches to the fourth dimension in his geometrically oriented

culpture, which also responded to Buckminster Fuller’s incorpora[1]tion of the

idea into his “synergetic geometry.”58 Both Duchamp’s notes and Fuller’s ideas

were important for Robert Smithson, for whom the spatial fourth dimension was a

central concern during the latter half of the 1960s, and for whom mirrors and

spirals were key signifiers of the idea.59

TONY ROBBIN: FOUR DIMENSIONAL ART

GROUNDED IN MATHEMATICS AND PHYSICS

The later twentieth-century artist who

has actually engaged four[1]dimensional geometry most fully—in the tradition of

Duchamp though seriously, not playfully—is Tony Robbin. Robbin arrived in New

York from graduate school at Yale University in 1969, two years after the Park

Place Gallery had closed its doors. But in an art world dominated by minimalism

and critic Clement Greenberg’s dogma of flatness in painting, space, in

general, was not a topic of artistic dis[1]cussion, and he never heard anything

of the Park Place artists’ inter[1]est in the fourth dimension.60 Robbin’s

paintings of the early 1970s are considered part of the pattern and decoration

movement, but he was particularly interested in the disjunctions between

contrasting areas of subtly colored patterns in his works. In a text

accompanying Robbin’s exhibit at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974,

curator Marcia Tucker wrote that the “contradictory visual informa[1]tion” in

Robbin’s paintings “suggests the complexity of four-dimen[1]sional geometry.”61

And in a scenario reminiscent of Forakis’s find, Robbin made contact with a

mathematics professor at Trenton State College where he was teaching, and into

his hands came a cache of sources on four-dimensional geometry and space,

including early twentieth-century books by H. P. Manning and Duncan

Sommerville, as well as Robert Marks’s Space, Time, and the New Mathematics.

Additionally discovering Coxeter’s Regular Polytopes, Robbin was launched on

his trajectory to become the most serious artist-scholar in four-dimensional

geometry of the twentieth century.6

From that point, Robbin undertook the

serious study of four[1]dimensional geometry, physics, and computer programming

that would support his creation of works such as his twenty-seven-foot painting

of 1980–1981, Fourfield (fig. 9), and the publication of his first book,

Fourfield: Computers, Art, and the Fourth Dimension, in 1992. In his quest to

convey the complexity of four-dimensional space as projected in three

dimensions, it was Thomas Banchoff’s rendering of the four-dimensional, planar

rotations of the hyper[1]cube in his 1978 film The Hypercube: Projections and

Slicings that held the key. Combining his exquisite sense of color with

sophisticated mathematical principles, Robbin has created a remarkable body of

work over more than thirty years. In Fourfield, for example, he painted a

richly textural, colored background of Necker-reversing, four- and six-sided

figures. To this mutating ground he then added painted lines and

three-dimensional rods extending from the can[1]vas surface, representing pairs

of isometric projections of the eight bounding cubes of the hypercube in slightly

altered positions. As a viewer walks from one end of Fourfield to the other,

the painted lines and white metal rods, both shadows of the hypercube, shift

and mu[1]tate, mimicking the distortions that occur in Banchoff’s projections

of the hypercube’s planar rotation in four-dimensional space.63

As documented in his book Fourfield and

his 2006 book Shadows of Reality, Robbin has worked over the years in close

consultation with a number of mathematicians and physicists. In doing so, he

has gained a level of expertise far beyond that of other artists and is

recognized for his contributions in mathematics as well as for the engineering

applications set forth in his 1996 book Engineering a New Architecture. 64

Robbin’s art continued to develop in new directions in tandem with his

explorations in mathematics and physics, including wire sculpture reliefs

illuminated by colored light and, subsequently, works grounded in the

principles of quasi-crystal geometry. More recently, Robbin has returned to

painting in a rich and sensuous pal[1]ette, combining mathematical structures

with painterly execution (fig. 10).65 Having been in dialogue with topologist

Scott Carter for the last several years, he now conceives of these paintings as

four[1]dimensional knot diagrams—with three-dimensional lattices, com[1]posed

of the polyhedra associated with quasi-crystals, interweaving with one another.

Carter has likewise credited his seeing one of Rob[1]bin’s wire-rod paintings

in the 1980s with helping him approach a problem in topology, and the more

recent collaborations of the two are supporting Carter’s further topological

investigations.66

As Robbin wrote in 2007, “[t]he artist

using mathematical ideas should not merely illustrate them; mathematical models

are to art as medical illustrations are to the work of Rembrandt. The goal is

to see the higher-dimensional space, to get the feeling of being inside them,

and to revel in their liberating possibilities.”67 Thirty years earlier, in

1977, he had declared in an article on “The New Art of 4-Dimensional Space”:

‘’ We are not in the least surprised .

. . to find physicists and mathematicians work[1]ing simultaneously on a

metaphor for space in which paradoxical three[1]dimensional experiences are

resolved only by a four-dimensional space. Our read[1]ing of the history of

culture has shown us that in the development of new metaphors for space

artists, physicists, and mathematicians are usually in step.68 ‘’

Soon after Robbin wrote this, the field

of computer graphics and the personal computer emerged as powerful new tools to

stimulate the visual imaginations of mathematicians and artists alike. Yet

whether by means of the computer or not, four-dimensional geometry and the multifaceted,

popular fourth dimension have served as key sources for artists in the

twentieth and now in the twenty-first century. Al[1]most a hundred years ago,

Malevich’s friend Matyushin pointed to the centrality of space to the activity

of the artist: “Artists have always been knights, poets, prophets of space in

all eras.”69 The subsequent development of art proved Matyushin himself to be

prophetic.

1 . A. G. Ingalls, “Hypergeometry and

Hyperperplexity,” Scientific American 161 (1939): 131. For the essay in

question, see Ralph Milne Farley, “Visualizing Hyperspace,” Scien[1]tific

American 160 (1939): 148–149.

2. David Hilbert, “Introduction” to D.

Hilbert and S. Cohn-Vossen, Geometry and the Imagination, trans. P. Nemenyi

(New York: Chelsea Publishing, 1952), p. iii.

3. See ibid., secs. 23, 44–51 (chap.

6). Di Suvero noted his interest in the book in a telephone interview with the

author on May 2, 2002. On the Park Place Gallery artists nd their interest in

topology and the fourth dimension, see Linda Dalrymple Hender[1]son, “Park

Place: Its Art and History,” in Reimagining Space: The Park Place Gallery in

1960s New York (Austin: Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas, 2008), pp.

8–11, 14–15, 20–24.

4. H. S. M. Coxeter, Regular Polytopes,

2nd ed. (1963; reprint, New York: Dover Publica[1]tions, 1973), p. vi.

5. See Linda Dalrymple Henderson, The

Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art (1983; new ed.,

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), chap. 1, as well as ap[1]pendix B for a

sampling of popular articles; see also Claude Bragdon, A Primer of Higher Space

(The Fourth Dimension) (Rochester, NY: Manas Press, 1913).

6. See Henry P. Manning, ed., The

Fourth Dimension Simply Explained (1910; reprint, New York: Dover Publications,

1960)

7 . On Einstein’s theories and their

reception, see, for example, Helge Kragh, Quantum Generations: A History of

Physics in the Twentieth Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Uni[1]versity Press,

1999).

8 For this history, see Henderson,

“Reintroduction: The Fourth Dimension Through the Twentieth Century,” in Fourth

Dimension (above, n. 5).

. Edward Kasner and James Newman,

Mathematics and the Imagination (New York: Si[1]mon & Schuster, 1940), pp.

119, 131.

10. Edwin A. Abbott, Flatland: A

Romance of Many Dimensions by a Square (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1950).

11. Casius J. Keyser, “Mathematical

Emancipations: The Passing of the Point and the Number Three: Dimensionality

and Hyperspace,” Monist 16 (1906): 83.

12. Henry Parker Manning, Geometry of

Four Dimensions (1914; reprint, New York: Do[1]ver Publications, 1956), pp.

15–16.

13. Charles Howard Hinton, A New Era of

Thought (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1888), pp. 6–7. For a summary of Hinton’s

ideas and the concept I termed “hyperspace phi[1]losophy,” see Henderson,

Fourth Dimension (above, n. 5), pp. 26–31; see also “Reintro[1]duction” (above,

n. 8).

14. See Charles Howard Hinton, The

Fourth Dimension (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1904).

15. For the “system” quote, see Hinton,

New Era (above, n. 13), pp. 86–87. On Hinton’s Scientific Romances, which were

issued by his publisher Swan Sonnenschein in London, see Bruce Clarke’s highly

insightful discussions of Hinton, idealist philosophy, thermo[1]dynamics, and

the ether in Energy Forms: Allegory and Science in the Era of Classical

Thermodynamics (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001), pp. 28–30,

111–121, 175–178.

16. See Henderson, “Reintroduction”

(above, n. 8), for this publishing history and a discussion of the impact of

Hinton’s writings as greater than I had realized in 1983.

17. See P. D. Ouspensky, Tertium

Organum: The Third Canon of Thought, a Key to the Engimas of the World, trans.

Claude Bragdon and Nicholas Bessaraboff (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1922).

18. Bertrand Russell, “New Books. The

Fourth Dimension. By Charles Howard Hinton,” Mind 13 (1904): 573–574.

19. For this science, including X-rays,

see Henderson, “Editor’s Introduction: II. Cub[1]ism, Futurism, and Ether

Physics in the Early Twentieth Century,” Science in Context 17 (2004): 445–466

20. For the measure of the impact of

the X-ray, see Lawrence Badash, Radioactivity in America: Growth and Decay of a

Science (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979), p. 9.

21. See again, for example, Henderson,

“Editor’s Introduction: II” (above, n. 19); and Linda Dalrymple Henderson,

“Modernism and Science,” in Modernism, ed. Astradur Eysteinsson and Vivian

Liska (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 2007), pp. 383– 403.

22. See, for example, Oliver Lodge,

“Electric Theory of Matter,” Harper’s Monthly Maga[1]zine 109 (1904): 383–389.

23. See Herschel Chipp, ed., Theories

of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1968), p. 223n1. Apart from Duchamp, Gris was the most

mathematically oriented of the cubists; see William Camfield, “Juan Gris and

the Golden Section,” Art Bulletin 47 (1965): 128–134.

24. For a useful introduction to

cubism, see Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, Cubism and Culture (New York:

Thames & Hudson, 2001).

25. Guillaume Apollinaire, “La Peinture

nouvelle: Notes d’art,” Les Soirées de Paris 3 (1912): 90–91. Apollinaire

slightly reworded his discussion of the fourth dimension in his 1913 Les

Peintres Cubistes; see note following for the “language of the studios”

reference in that context, as well as Henderson, Fourth Dimension (above, n.

5), pp. 74–81, where these texts are analyzed. For Picasso’s statement, see

Ramón Gómez de la Serna, “Completa y verídica historia de Picasso y el

cubismo,” Revista de Occidente 25 (1929): 100.

. Guillaume Apollinaire, The Cubist

Painters: Aesthetic Meditations, ed. Robert Moth[1]erwell and trans. Lionel

Abel, in The Documents of Modern Art series (New York: Wit[1]tenborn, 1944), p.

30; for his section on the fourth dimension, see p. 12.

27. Linda Dalrymple Henderson, “A New

Facet of Cubism: ‘The Fourth Dimension’ and ‘Non-Euclidean Geometry’

Reinterpreted,” Art Quarterly 34 (1971): 410–433; see also [sprit Pascal]

Jouffret, Traité élementaire de géométrie à quatre dimensions (Paris:

Gauth[1]ier-Villars, 1903).

28. See Tony Robbin, Shadows of

Reality: The Fourth Dimension in Relativity, Cubism, and Modern Thought (New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), pp. 30–33. Arthur Miller rightly

connects Picasso to Poincaré versus Einstein in Einstein, Picasso: Space, Time

and the Beauty That Causes Havoc (New York: Basic Books, 2001), but loses sight

of Picasso’s artistic context, reducing him to Princet’s willing geometry

student. For further discus[1]sion of Miller’s book and others, see Linda

Dalrymple Henderson, “Four-Dimensional Space or Space-Time?: The Emergence of

the Cubism-Relativity Myth in New York in the 1940s,” in The Visual Mind II,

ed. Michele Emmer (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), pp. 384–386n16. On the

earliest usages of the term “fourth dimension” in Pari[1]sian art circles,

which was not specifically geometric, see Henderson, “Reintroduction” (above,

n. 8).

29. Robbin, Shadows (above, n. 28), p.

33.

30. Henri Poincaré, La Science et l’hypothèse

(Paris: Ernest Flammarion, 1902), pp. 89–90. On the debt of Metzinger and his

fellow artist-author Albert Gleizes to Poincaré’s ideas on tactile and motor

sensations, including his assertion that “[m]otor space would have as many

dimensions as we have muscles,” see Henderson, Fourth Dimension (above, n. 5),

pp. 81–85.

31. See Henderson, “Four-Dimensional

Space or Space-Time?” (above, n. 28), for the rise of the cubism–relativity

myth. For a sampling of articles written on the supposed cub[1]ism–relativity

connection, see Henderson, Fourth Dimension (above, n. 5), appendix A.

32. On this subject, see Henderson,

“Editor’s Introduction: II” (above, n. 19), and “Modernism and Science” (above,

n. 21); see also Henderson, “Reintroduction” (above, n. 8), which addresses

Balfour Stewart and P. G. Tait’s The Unseen Universe (1875), the first source

to link the ether to the fourth dimension.

33. Maurice Boucher, Essai sur

l’hyperespace: Le Temps, la matière, et l’énergie (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1903),

p. 64; see also Jean Metzinger, Le Cubisme était né (Chambéry: Editions

Présence, 1972), p. 43.

34. For a fuller discussion of the

Russian avant-garde and the fourth dimension, see Henderson, Fourth Dimension

(above, n. 5), chap. 5; for an excellent study of Malevich’s art, see Charlotte

Douglas, Kazimir Malevich (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994).

35. M. Matyushin, as quoted in Larissa

A. Zhadova, Malevich: Suprematism and Revolu[1]tion in Russian Art 1910–1930

(London: Thames & Hudson, 1982), p. 32. In Ouspen[1]sky’s 1914 revised

edition of Tertium Organum, the Russians would have heard briefly about

Minkowski’s four-dimensional space-time continuum, since Ouspensky quoted from

a 1911 lecture by physicist N. A. Umov on the subject. However, Ouspensky also

critiqued Umov for failing to embrace his belief that time and motion were

illusions that would fade away with the advent of higher-dimensional

consciousness; see Ous[1]pensky, Tertium Organum (above, n. 17), chap. 11.

36. For an overview of Ouspensky’s philosophy, see Henderson, Fourth Dimension (above, n. 5), pp. 245–255. Initially, his advocacy of the practice of alogical logic in order to achieve higher, four-dimensional consciousness had supported Kruchenykh’s creation of his transrational zaum language in 1913 and Malevich’s alogist style of painting during 1913–1914; see ibid., pp. 269–279.

37. Hinton wrote: “All attempts to

visualize a fourth dimension are futile. It must be connected with a time

experience in three space” (ibid., p. 207). For Ouspensky’s dis[1]cussion of

this issue, see Tertium Organum (above, n. 17), chap. 4.

38. Matyushin diary entry, May 29,

1915; see Henderson, Fourth Dimension (above, n. 5), p. 284n173.

39. Malevich, “Non-Objective Creation

and Suprematism” (1919), in K. S. Malevich: Essays on Art 1915–1933, 2 vols.,

ed. Troels Andersen (Copenhagen: Borgen, 1971), p. 1:122. For Ouspensky’s

discussion on infinity and cosmic consciousness, see Tertium Organum (above, n.

17), chap. 20.

0. The discussion of the Large Glass

that follows is drawn from Linda Dalrymple Hen[1]derson, Duchamp in Context:

Science and Technology in the Large Glass and Related Works (Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, 1998); for an overview, see Henderson, “The Large

Glass Seen Anew: Reflections of Contemporary Science and Technology in Marcel

Duchamp’s ‘Hilarious Picture,’” Leonardo 32:2 (1999): 113–126. Duchamp’s

engage[1]ment with the fourth dimension (sans science) is the topic of a

chapter in Henderson, Fourth Dimension (above, n. 5). The best general introduction

to the artist is Dawn Ades, Neil Cox, and David Hopkins, Marcel Duchamp

(London: Thames & Hudson, 1999).

41. Duchamp, as quoted in James Johnson

Sweeney’s 1946 interview, Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art; reprinted in

The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Michel Sanouil[1]let and Elmer Peterson

(1973; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1988), p. 125.

42. For Duchamp’s rejection of

“retinal” art in favor of “gray matter,” see James John[1]son Sweeney’s 1956

NBC television interview with Duchamp, reprinted in ibid., p. 136. For

Duchamp’s notes published during his lifetime, see ibid.; for the preparatory

notes discovered after his death, see Marcel Duchamp: Notes, ed. and trans.

Paul Matisse (Bos[1]ton: G. K. Hall, 1983). These unpublished notes are particularly

rich in scientific con[1]tent and are analyzed in detail in Henderson, Duchamp

in Context (above, n. 40).

43. On the Large Glass and allegory,

see Linda Dalrymple Henderson, “Etherial Bride and Mechanical Bachelors:

Science and Allegory in Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Large Glass,’” Configurations 4

(1996): 91–120, and Duchamp in Context (above, n. 40), chap. 12.

44. For “splendid vibrations,” see

Duchamp, The Green Box, in Writings (above, n. 41), p. 42; for these aspects of

the Large Glass, see Henderson, “The Large Glass Seen Anew” (above, n. 40).

45. For “hilarious picture,” see

Duchamp, The Green Box, in Writings (above, n. 41), p. 30.

46. See Duchamp, A l’infinitif, in

ibid., pp. 84–101. For an overview of these notes, see Henderson, Fourth

Dimension (above, n. 5), chap. 3. Craig Adcock has made the most extensive

study of these particular notes, in Marcel Duchamp’s Notes from the “Large

Glass”: An N-Dimensional Analysis (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1983).

47. Duchamp, A l’infinitif, in Writings

(above, n. 41), p. 89. The note continues: “(see Jouffret, Géom. à 4 dim., page

186, last 3 lines.).”

48. Duchamp, The Green Box, in ibid.,

pp. 44–45.

49. On Duchamp’s embrace of “logic and

close mathematical thinking,” which he as[1]sociated with Cartesianism, see

Henderson, Duchamp in Context (above, n. 40), pp. 77, 269n59; for Boucher’s

advocacy of reason, see, for example, Boucher, Essai (above, n. 33), pp. 144,

170.

50. For the Juggler, see Duchamp, The

Green Box, in Writings (above, n. 41), p. 65; for Jean Suquet’s drawing that

superimposes the Juggler onto the Large Glass, see Henderson, “Etherial Bride”

(above, n. 43), as well as Duchamp in Context (above, n. 40), fig. 111.

51. See Hinton, Fourth Dimension

(above, n. 14), p. 27; and Henderson, Fourth Dimen[1]sion (above, n. 5), fig.

32.

52. On spirals or mirrors and the

fourth dimension, see Henderson, Fourth Dimension (above, n. 5), index; on

Lewis Carroll, pseudonym of mathematician Charles Dodgson, see ibid., pp.

21–22.

53. On this development as well as on

Moholy-Nagy, see Linda Dalrymple Henderson, “Einstein and 20th-Century Art: A

Romance of Many Dimensions,” in Einstein for the 21st Century: His Legacy in

Science, Art, and Modern Culture, ed. Peter L. Galison, Gerald Holton, and

Silvan S. Schweber (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), pp.

101–129.

54. Jacqueline Monnier (Duchamp’s

stepdaughter), letter to author, July 20, 2001.

55. For an “archeology” of the traces

of the fourth dimension as they emerged during the 1960s, including Gardner,

see Henderson, “Reintroduction” (above, n. 8).

56. See Marc Scott Zicree, The Twilight

Zone Companion (New York: Bantam Books, 1992), p. 31.

57. Arthur C. Clarke, Profiles of the

Future (New York: Harper & Row, 1962), p. 78.

58. See Henderson, “Einstein and

20th-Century Art” (above, n. 53), pp. 124–125; for a fuller discussion of

Forakis, see Henderson, “Park Place” (above, n. 3).

59. On Smithson and the fourth

dimension, see Henderson, “Reintroduction” (above, n. 8); for a concise

version, see Linda Dalrymple Henderson, “Space, Time, and Space[1]Time:

Changing Identities of the Fourth Dimension in 20th-Century Art,” in Measure of

Time, ed. Lucinda Barnes (Berkeley: Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film

Archive, 2007), pp. 95–99.

60. For Robbin’s early work and

history, see Fourfield: Computers, Art, and the Fourth Dimension (Boston:

Bullfinch Press, 1992); on the critical views that militated against artists’

interest in space during the later 1960s, see Henderson, “Park Place” (above,

n. 3), pp. 35–41.

61. Marcia Tucker, Tony Robbin (New

York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1974). Tucker, who knew the Park Place

artists, may well have encountered the idea of the spatial fourth dimension

there.

62. Tony Robbin, e-mail message to

author, October 12, 2003.

63. Banchoff’s film, which he showed

around the world, accompanying it with lectures, was highly influential in

spreading news of the spatial fourth dimension. Robbin discusses his work with

Banchoff in Fourfield (above, n. 60), and addresses “The Computer Revolution in

Four-Dimensional Geometry” in chapter 10 of his Shadows of Reality (above, n.

28).

64. Shadows of Reality (above, n. 28)

contains a passionate argument for the model of projections versus slicing as a

way to understand dimensional relationships in mathe[1]matics and physics; for

example, Robbin makes a close rereading of Minkowski’s papers of 1907 and 1908

that interprets the space-time continuum as a geometry of projec[1]tion, rather

than the common interpretation of a slicing of worldliness (chap. 4). His

chapter 1 includes an unprecedented history of early techniques for rendering

four[1]dimensional objects.

65. For the various phases of Robbin’s

development, see Fourfield (above, n. 60) and Shadows of Reality (above, n.

28); he recounts his interactions with mathematicians and physicists in both

Fourfield (numerous sidebars) and Shadows. Among the exchanges discussed in the

latter work is that with quantum physicist P. K. Aravind, for whom

four-dimensional projective geometrical figures have become important to his

research on particle entanglement (pp. 85–92).

66. Scott Carter, e-mail message to

author, August 3, 2004. According to Carter, “Tony’s painting spoke directly to

me since I had seen glimpses of 4-space in my own research. He had escaped the

plane of the canvas in order to explain escaping the plane of the 3-dimensional

world.”

67. Tony Robbin, unpublished statement

(2007).

68. Tony Robbin, “The New Art of

4-Dimensional Space: Spatial Complexity in Recent New York Work,” Artscribe 9

(1977): 20.

69. M. V. Matyushin, “Of the Book by

Gleizes and Metzinger, Du Cubisme,” Union of Youth 3 (1913): 25, reprinted in

Henderson, Fourth Dimension (above, n. 5), appendix C.

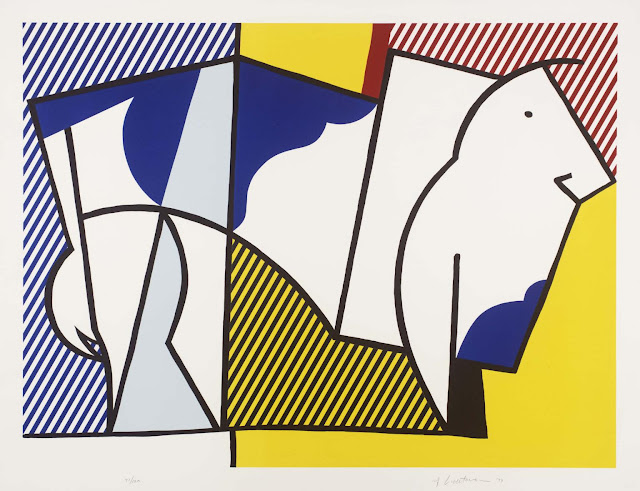

ROY

LICHTENSTEIN 1923 – 1997

MODERN

ART I 1996

Screenprint

on Paper

Dimensions:

Object: 1302 × 962 mm

Frame: 1412 × 1078 × 46 mm

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein/DACS 2021

Modern Art I 1996 was published by Gemini

G.E.L. in Los Angeles and is recorded in the second volume of the catalogue

raisonné of the artist’s prints (Corlett and Fine 2002). It is part of a series

of Modern Art prints that Lichtenstein made during 1996, the

year before he died. Another example, Modern Art II 1996

(Tate AL00382), is also in Tate’s collection. In Modern

Art I Lichtenstein explored the refracted style of cubism found in the

work of modern masters such as Pablo Picasso. However, in Lichtenstein’s hands,

with his use of Benday dots, blocks of colour and stark black outlines, the

dislocated features are transformed into highly stylised imagery more common to

slick cartoons and comic books. In Modern Art II Lichtenstein

explored the cubist style further, in particular the dislocated figurative

imagery of Picasso. The nose, with its starkly painted striations, suggests a

reference to the imagery Picasso used in paintings such as Les

Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907 (Museum of Modern Art, New York). Tate’s

copy of Modern Art I is number three of ten artist’s proofs

aside from the edition of fifty.

From the early

1960s Lichtenstein made works that focused on the work of modern masters, such

as the painting Woman with Flowered Hat 1963. Speaking about

this painting, Lichtenstein explained:

Instead

of using subject matter that was considered vernacular, or everyday, I used

subject matter that was celebrated as art. What I wanted to express wasn’t that

Picasso was known and therefore commonplace. Nobody thought of Picasso as

common. What I am painting is a kind of Picasso done the way a cartoonist might

do it, or the way it might be described to you, so it loses the subtleties of

Picasso, but it takes on other characteristics: the Picasso is converted to my

pseudo-cartoon style and takes on a character of its own. Artists have often

converted the work of other artists to their own style.

(Roy Lichtenstein, ‘A Review of My Work Since 1961’, in Bader 2009, p.61.)

Elsewhere,

Lichtenstein noted:

I’ve

always been interested in Matisse but maybe a little more interested in

Picasso. But they are both overwhelming influences on everyone, really. Whether

one tries to be like them or tries not to be like them, they’re always there as

presences to be dealt with. They’re just too formidable to have no interest. I

think that somebody who pretends he’s not interested is not interested in art.

(Ibid., p.55.)

Lichtenstein was

born in New York, and was a central player in American pop art. He came to

prominence in the 1960s, making works based on imagery from comic strips, such

as In the Car and Whaam! 1963 (Tate T00897). In these works he used the Benday dot, common to

newspaper and magazine reproduction, to produce works that appeared

mechanically reproduced, and which in fact are even more stylised than the

cartoons Lichtenstein appropriated. Printmaking was an integral part of his

practice throughout his career from the late 1950s through to the 1990s.

Further reading

Mary Lee Corlett and Ruth E. Fine, The Prints of Roy Lichtenstein: A Catalogue Raisonné: 1948–1997,

New York and Washington D.C., revised and updated second edition 2002.

Graham Bader (ed.), OCTOBER Files

7: Roy Lichtenstein, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London 2009.

Gianni Mercuri (ed.), Roy Lichtenstein: Meditations on Art,

Milan 2010.

James Rondeau and Sheena Wagstaff, Roy

Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London

and Art Institute of Chicago 2012.

Lucy Askew

Senior Curator, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

August 2014

Amended by Stephen

Huyton

Assistant Collection Registrar, ARTIST ROOMS

September 2017

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lichtenstein-modern-art-i-al00381

ROY LICHTENSTEIN 1923–1997

WHAAM! 1963

Acrylic

Paint and Oil Paint on Canvas

Dimensions:

Support: 1727 × 4064 mm

frame: 1747 × 4084 × 60 mm

ROY LICHTENSTEIN 1923–1997

BULL III - 1973

Lithograph,

Screenprint and Line - Cut on Paper

Dimensions: Image: 685 × 890 mm

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein/DACS 2021

ROY LICHTENSTEIN 1923–1997

REFLECTIONS ON GIRL 1990

Lithograph,

Screenprint on Paper and Metalised PVC on Paper

Dimensions:

Object: 1146 × 1391 mm

Frame: 1302 × 1552 × 65 mm

ROY LICHTENSTEIN 1923–1997

REFLECTIONS ON THE SCREAM 1990

Lithograph,

Screenprint, Woodcut on Paper and Metalised PVC on Paper

Dimensions:

Object: 1238 × 1661 mm

Frame: 1396 × 1815 × 65 mm

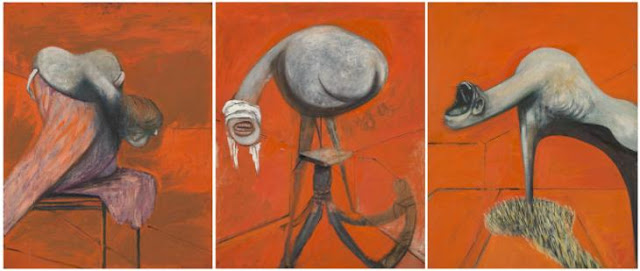

FRANCIS

BACON 1909 – 1992

PORTRAIT

OF ISABEL RAWSTHORNE 1966

Oil

Paint on Canvas

Dimensions:

Support: 813 × 686 mm

Frame: 943 × 793 × 59 mm

FRANCIS

BACON 1909–1992

THREE

STUDIES FOR FIGURES AT THE BASE OF A CRUCIFIXION 1944

Oil

Paint on 3 Boards

Dimensions:

Support, each: 940 × 737 mm

Frame, Each: 1162 × 960 × 80 mm

FRANCIS

BACON 1909 – 1992

SECOND

VERSION OF TRIPTYCH 1944, 1988

Dimensions:

Oil Paint and Acrylic Paint on 3 Canvases

Support,

Each: 1980 × 1475 mm

Frame (Each): 2178 × 1668 × 100 mm

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE 1946 - 1989

SELF PORTRAIT 1988

Photograph, Gelatin Silver Print on Paper

Dimensions:

Support: 577 × 481 mm

Frame: 850 × 747 × 22 mm

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE 1946 - 1989

SELF PORTRAIT 1985

Photograph,

Gelatin Silver Print on Paper

Dimensions:

Image: 384 × 386 mm

Frame: 684 × 662 × 31 mm

ROBERT

MAPPLETHORPE 1946 -1989

LOUIS

BOURGEOIS 1982, PRINTED 1991

Photograph,

Gelatin Silver Print on Paper

Dimensions:

Support: 375 × 374 mm

Frame: 645 × 620 × 38 mm

FERNAND LEGER 1881 – 1955

TWO WOMEN HOLDING FLOWERS 1954

Oil

Paint on Canvas

Dimensions:

Support: 972 × 1299 mm

Frame: 1100 × 1432 × 80 mm

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021

Two

Women Holding Flowers is a

large oil on canvas painting by French artist Fernand Léger, made in 1954. Two

stylised nude female forms, on occupy most of the picture plane. One sits while

the other reclines, their forms intermingling and contorting, fitting neatly

along the length and breadth of the canvas. It is unclear where one body ends

and the other begins. Their limbs form a loose rectangle within the painting

and both women gaze directly out at the viewer. The reclining woman holds a

flower by its stem while the seated woman reaches out towards her companion.

The figures have thick black outlines with touches of grey paint giving

definition to an otherwise flat composition. Parts of their bodies, such as

their breasts, faces and hair, have been delineated in a highly stylised

manner. Flat, bold areas of red, blue, yellow and orange overlay parts of the

figures. The background is plain white, apart from the inclusion of what may be

a window at the right-hand edge of the image. Léger has signed and dated the

painting in black paint in the bottom right corner.

It is

likely that Léger painted this work in his studio in Gif-sur-Yvette, Chevreuse,

to which he moved in 1952. It was produced by applying oil paint in

decisive, bold brushstrokes. The contour lines of the figures have been painted

over the flat areas of colour. Two earlier versions of this composition are

known to exist, both from 1954: the first is a smaller oil painting showing

some variation in colour, pattern and shading, and the second is a small

gouache with a very similar composition to Two Women Holding Flowers,

but a different arrangement of colours.

The

traditional theme of the nude was a regular feature of Léger’s art and had

played an important role in the cubist revival of neo-classicism spearheaded by

Pablo Picasso after the First World War. Art historian Yve-Alain Bois has

described how in the post-war period Léger, unlike many of his colleagues,

‘opted for the heroic–monumental genre’ (Foster, Krauss, Bois and others 2004,

p.316). He often paired female nudes in an image in order to explore the

rhythmic patterns of the body. An earlier example is The Two

Sisters 1935 (Staatliche Museen Preussicher Kulturbesitz,

Nationalgalerie, Berlin). Two Women Holding Flowers was

produced at a time when Léger, a committed socialist and communist, was

painting energetic images of builders, circus performers and lively scenes of

modern life. Although Two Women Holding Flowers lacks a

precise narrative, its boldly contorted figures can be regarded an equally

modern exploration and celebration of shape and form.

The

use of bright primary colours was, by 1954, an established feature of Léger’s

work and his preoccupation with a ‘rigorously clear vision of forms and

colours’ has been traced by art historian André Verdet to his La Femme

en bleu 1912 (Kunstmuseum, Basel). Léger explained how his use of

colour diverged from that of his close associate and founder of orphism, Robert

Delaunay:

He

continued the Impressionist tradition of juxtaposing complementary colours, red

against green. I did not want to use two complementary colours together any

more. I wanted to isolate the colours, to produce a very red red a very blue

blue. If one places a yellow next to a blue, one immediately produces a