MOTION AUTOS, ART, ARCHITECTURE AT GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM BILBOA

MOTION AUTOS,

ART, ARCHITECTURE AT GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM BILBOA

April 8, 2022

– September 18, 2022

· Concept and Design by Norman Foster, curated with Lekha

Hileman Waitoller and

· Manuel Cirauqui of Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and a team from

the Norman Foster Foundation and its collaborators. Exhibition organized by the Guggenheim Museum

Bilbao and the Norman Foster

· Foundation Sponsored

by Iberdrola and Volkswagen Group.

· Collaborators: AIC-Automotive Intelligence Center in

Future, Cadillac in Clay Modelling

· Studio and Sennheiser in the immersive sound

experience.

· Benefactor: Gestamp

- Beginnings, Sculptures, Popularising,

Sporting, Visionaries, Americana, and Future, are the thematic titles of the

galleries that guide the chronological structure of the exhibition.

- Each gallery in this unique exhibition

addresses a particular historical moment or theme in which the intersection of

industrial design, art, and architecture are visible.

- Clay Modelling Studio, presented by Cadillac

brings a replica of a clay modelling studio featuring the brand’s first all -

electric vehicle LYRIQ, to illustrate both original and contemporary production

techniques.

- For Future sixteen schools of design and

architecture from around the globe consider today’s problems of urban

congestion, resource scarcity, and pollution and present visions for the future

of mobility by a new global generation of architects, designers and artists.

This gallery has received the support of AIC-Automotive Intelligence Center.

The

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao presents Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture, sponsored

by Iberdrola and Volkswagen Group. The exhibition celebrates the artistic

dimension of the automobile and links it to the parallel worlds of painting,

sculpture, architecture, photography, and film. Taking a holistic approach, the

exhibition challenges the separate silos of these disciplines and explores how

they are visually and culturally linked.

The

exhibition considers the affinities between technology and art, showing for

example how use of the wind tunnel helped to aerodynamically shape the

automobile to go faster with more economic use of power. This streamlining

revolution was echoed in works of the Futurist movement and by other artists of

the period. It was also reflected in the industrial design of everything from

household appliances to locomotives.

The

exhibition brings together around forty automobiles – each the best of its kind

in such terms as beauty, rarity, technical progress and a vision of the future.

These are placed centre stage in the galleries and surrounded by significant

works of art and architecture. Many of these have never before left their homes

in private collections and public institutions, and as such, are being

presented to a wider audience for the first time.

The

exhibition is spread over ten spaces in the museum. Each of seven galleries is

themed in a roughly chronological order. These start with Beginnings and

continue as Sculptures, Popularising, Sporting, Visionaries and Americana and

close with a gallery dedicated to what the future of mobility may hold.

Future shows

the work of a younger generation of students from sixteen schools of design and

architecture on four continents, who were invited by the Norman Foster

Foundation to imagine what mobility might be at the end of the century,

coinciding roughly with the 200th anniversary of the birth of the automobile.

The remaining

four spaces comprise a corridor containing a timeline and immersive sound

experience, a live clay-modelling studio and an area devoted to models.

Unlike any

other single invention, the automobile has completely transformed the urban and

rural landscape of our planet and in turn our lifestyle. We are on the edge of

a new revolution of electric power, so this exhibition could be seen as a

requiem for the last days of combustion.

A summary of

each of these galleries and spaces is as follows.

https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/exhibitions/motion-autos-art-architecture

CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI

Bird in Space

1932 – 1940

Polished

Brass

Dimension:

151.7 cm.

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection Venice ( Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation )

©Succession Brancusi – All Rights reserved (VEGAP) 2022

BEGINNINGS

This gallery

traces the birth of the automobile from the customised horseless carriage

through to its massproduction – a process viewed within the concept of motion

in the late 19th century using new technologies of photography and film. The

automobile evolved from box-like angularity to sleek aerodynamic shapes, influenced

by utilisation of the wind tunnel. This streamlined form was anticipated by the

work of artists and architects in the first decades of the 20th century, and in

the automobile, it became the very symbol of modernity.

In the

beginning, the automobile rescued cities from the stench, disease and pollution

caused by horsedrawn vehicles. In an era of climate change the automobile has

now become the polluting urban villain.

However,

battery power was also a dominant force from the earliest days of motoring. Included

in the show is an example of the Porsche Phaeton of 1900 with electric motors

embedded in the wheel hubs - a concept considered revolutionary when it drove

NASA’s first buggy on the moon.

History has

come full circle as we are on the edge of a new revolution with electric

propulsion coupled with “mobility as a service” such as ride hailing and

sharing, along with the prospect of self-driving vehicles.

BUGATTI, TYPE

35, 1924

National

Motor Museum Beaulieu, United Kingdom

Photo ©Courtesy National Motor Museum Beaulieu

ALBERT KAHN

Ford Motor Company Highland Park Rendering bird's eye view

in 1924, 1924

Ink on Paper

Dimensions: 85.4 x 227.3 cm

Collection Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

Gift of the Estate of John Bloom

CHARLES

SHEELER

Criss-Crossed

Conveyors, River Rouge Plant,

Ford Motor

Company

Dimensions:

25.4 x 20.32 cm.

The Henry Ford, United States

ANDY WARHOL

Benz Patent Motor Car (1886), 1986

Silkscreen, Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 153 x 128 cm

Acquired 1986, Mercedes-Benz Art Collection, Stuttgart /

Berlin

© 2022, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts,

Inc./VEGAP

Photograph: Uwe Seyl, Stuttgart

HUGH FERRISS

Chrysler

Building in New York City, 1929

Drawing

St. Louis Public Library, United States

MARGARET BOURKE – WHITE

A DC-4 Flying Over New York City, 1939

Photograph

Dimensions: 76.2 x 96.5 cm

Print Number 6/40

Foster Family Collection

© Margaret Bourke-White, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2022

© LIFE Gallery of Photography

GIACOMO BALLA

Speeding

Automobile, 1913

Coloured

Crayon on Paper

Dimensions:

24.5 x 29.5 cm.

Estorick

Collection, London, United Kingdom

©Giacomo

Balla, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2022

© Estorick Collection / Bridgeman

BENZ, PATENT

– MOTOR CAR, 1886

Mercedes-Benz

Museum, Germany

Photo ©Mercedes-Benz AG.

ELEKTRISCHER

PHAETON, MODELI

Nr. 27,

System Lohner Porsche, 1900

Technisches

Museum Wien Mit Osterreichischer Mediathek.

Photo © Technisches Museum Wien

LE CORBUSIER

Vertical

Guitar 1920

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions:

100 x 81 cm.

Fondation Le

Corbusier, Pais, France.

©F.L.C. (VEGAP) 2022

SONAI

DELAUNAY

Untitled 1916

Watercolour

on Paper

Dimensions:

36 x 26 cm.

Estate of Antonio de Guezala

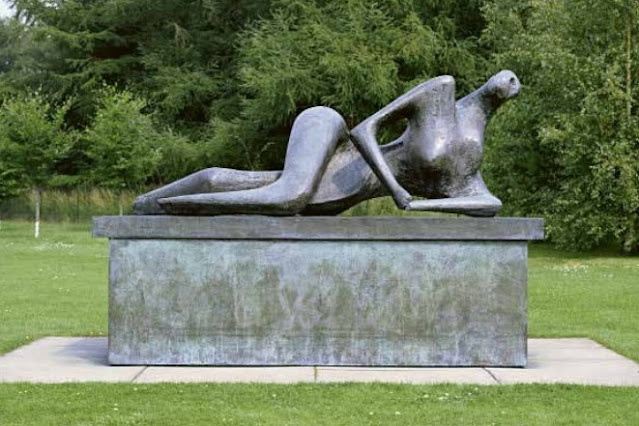

SCULPTURES

The description of automobiles as “hollow

rolling sculptures” was made by the late Arthur Drexler in the early 1950’s.

That proposition is affirmed by juxtaposing four of the most beautiful

automobiles of the twentieth century with sculptures by two of the greatest

artists of the same period - the soft curves of Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure

and the restlessly fluid motions of Alexander Calder’s monumental mobile 31st

January.

Each of the

automobiles stand as examples of technical excellence – two of them laid claim

to being the fastest production vehicles on the road – but it is the beauty of

their flowing lines that that are celebrated here.

Like great works of art, the Bugatti Type 57SC

Atlantic, Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet Xenia and Pegaso Z-102 Cúpula hold rare

value as limited editions for connoisseurs. Even the mass-produced Bentley

RType Continental numbered only around 200 examples. In another link with the

artist’s studio, the body shells of these automobiles were individually shaped

by craftsmen, coaxing the metal by hand to create the compound curves.

The Atlantic,

created by Jean Bugatti, was linked to a family immersed in the world of art

and architecture over several generations. Here alongside the automobile is the

sculpture Walking Panther by the uncle, artist Rembrandt Bugatti, each redolent

of motion.

ALEXANDER CALDER

January 31 (31 Janvier), 1950

Aluminium Sheet and Painted Steel Wire

Dimensions: 385 x 575 cm

Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne / Centre de Creation

Industrielle, Paris, Francia. Purchased by the State, 1950.

Attributed 1959

© 2022 Calder Foundation, New York / VEGAP, Madrid

JEAN BUGATTI

Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic, 1936

Merle & Peter Mullin, Melani & Rob Walton and the

Mullin

Automotive Museum Foundation

© Photograph by Michael Furman

HISPANA

SUIZA, H6B DUBONNET XENIA, 1938

Merle Peter

Mullin and the Mullin Automotive Museum Foundation, United States

© Photograph by Michael Furman

WIFREDO RICART

Pegaso Z-102 Cúpula, 1952

Louwman Museum

© Louwman Museum

HENRY MOORE

Reclining

Figure, 1956

Bronze

Dimensions:

224 x 90 cm.

Robert and

Lisa Sainsbury Collecton, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts,

University of

East Anglia, United Kingdom

©Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation

MODERNISM, AUTOMOBILES AND ARCHITECTS BY IVAN MARGOLIUS

Automobiles are one of the products of Modernism. The

sculptural volume and lines of car bodies, enhanced by movement and the rules

of streamlining that were established in the early 1920s, reflect a Modernist

approach to art and design. At this time, automobiles became a symbol of

progress and the bearer of expectations regarding future design innovations to

come. In artistic circle, the car wheel was considered one of the most ideal

aesthetic forms due to the perfection of its functionality as well as its

poetic nature. It was associated with the machine and with the idea of minimum

effort coupled with maximum effect. In 1921, the Dutch architect Jacobus

Johannes Pieter Oud wrote:

Automobiles, steamers, yachts … possess

within themselves, as the purest expression of their time, the elements of a

new language of aesthetic form, and can be considered as the point of departure

for a new art, through their restrained form, lack of ornament and plain

colours, the comparative perfection of their materials and the purity of their

proportion.1

Modernism was a broad collection of creative ideas and

principles shared by artist and architects during the twentieth century,

through which they strived for innovation and unity in all the arts. It centred

on the recognition that developments in the arts were increasingly dependent on

advances in science, industry, engineering and technology, and the use of new

materials in the service of modern society. Modernist creativity was the

consequence of the human search for evolution and for novel forms of

expression. Its proponents aimed to rework or abandon elements from the past,

striving to build a better world by rejecting history and breaking with

tradition.

The modernist form of the design world were based on the

harmony of clean horizontal, perpendicular, diagonal and curved lines expressed

in dynamic movement that would convey powerful messages to their observers.

This was shaped by ideas from scientific, technological, industrial, transport

and engineering design, which were transposed into the field of artistic

design. This, as well as the optimism of the time, provided artists with the

fertile ground for developing new visions and forms.

Alongside automobile engineers, constructors, coachbuilders

and stylists, many architects love cars and their sculptural volumes, and

designing them offers a fitting exercise in small-scale creativity, a way of

testing their design skills. For architects, it is an opportunity to perfect

the synthesis of art, design and the latest technology, It may seem

contradictory that architects, as designers of stationary objects, should

concern themselves with automobile design, but the automobile has long stirred

architects’ imagination and passion – many regard the car as a house on wheels,

or mobile accommodation. Architects are also fascinated by automobile design

because of its constant forward outlook, always remaining in step with the

latest technology.

Architectural education trains architect as designers to

reconcile all aspects of humans’ practical and emotional attitudes to their

environment. This develops in architects a deep need to understand human

aspirations, desires, lifestyles, cultures and trends, in order to make buildings

that complement the ever – changing scene of human existence.

By getting involved in automobile design architects have

learned and found inspiration for the art craft of building, leading them to

transfer this newfound experience into innovative architectural ideas. They

recognized that automobile bodies and interiors could inspire their buildings’

construction, proportions, flowing lines, materials and finishes, colours and

comfort criteria, satisfying the spirit of Modernism through an emphasis on

beautiful forms. Le Corbusier believed that architects should study machines

such as automobiles in order to find standards on which to base modern

architectural principles.

Car interiors often mirror the comfort of the living room

and have become a perfect exercise in interior design-in many cases with better

results than are achieved in most homes. In 1940, the American designer Walter

Dorwin Teague pointed this out, nothing that ‘ the automobile makers have made,

in the past few years, a greater contribution to the art of confortable seating

than chair builders has made in all preceding history’.2

On the surface, there is very little comparison between automobile and architectural design. Architectural design almost always starts from a blank canvas, because a building’s design is usually specific to factors such as the client’s brief, site, purpose and situation. Although there are building regulations, fire-prevention and safety measures, planning directives, materials standards and codes, budgets, services, and structural, ergonomic and environmental criteria to follow, it is each architect’s desire to produce a personal, original answer to the client’s requirements and that is why there are no two building designs exactly alike.

The car industry works in the opposite way. There are safety

criteria and composite requirements concerning mechanics, structure, engine

size, performance, road holding, fuel economy, production parameters, affordability,

comfort and aesthetics, all of which essentially remain the same from model to

model. In the case of a new design, this will be based on the previous model’s

component and design development so as to reduce the enormous costs involved in

retooling the production line. Once a prototype is created, which might take

several years of research and development-unlike in architecture, where there

are only a few months or weeks to prepare drawings for construction-the car

then goes into mass production.

One significant way in which automobile design differs from

architectural expression is in the desire to empasise the car’s forms through

the play of light on their surfaces. The automobile’s polished metal or shiny

paint finish intentionally reflects light and shade, and enhances or creates

contrast between its lines, contours, colours, indentations and protrusions.

A number of well-known Modernist architects designed

innovative automobiles, including Frank Lloyd Wright, Adolf Loos, Walter

Gropius, Le Corbusier and Richard Buckminster Fuller.

Wright bought scores of automobiles, including a Packard, a

Cord, a Lincoln Continental and a Mercedes-Benz 300 SL, endeavouring to own

most of the new models introduce into the market. These Machines inspired his

designs. In 1920, he sketched out a car body with a cantilevered top, sloping

radiator and windows with brise soleil louvers. In the 1950s, he designed a

three – seater city taxi with two large engine-driven wheels with single

smaller wheels at the front and rear to ease manoeuvrability.

In 1923, Loos proposed a car design based on a monocoque

Lancia Lambda chassis, using the concept of Raumplan-an idea he employed when

designing buildings-in raising the rear level of the car to allow an unimpeded

view of the road from the back seats.

For the German firm Adler, Gropius designed luxury Favorit

and Standard cabriolets and limousines, which were manufactured in the early

1930s. The cars had chromed radiators and with an added architect’s touch,

seats that could be arranged into sleeping couchettes.

Le Corbusier owned Voisin Lumineuse models that met his

architectural standards and embodied his five points of architecture: the

Voisins were raised above the ground on wheels (the equivalent of

pilotis-pillars or supports), and they had a simple plan, a horizontal band of

windows all around, a free façade and a flat roof. This was not suprising as

their bodies had been designed by an architect, Andre ‘ Noel-Noel’ Telmont. Le

Corbusier carefully placed his Voisin in several photographs of his completed

buildings to emphasise the perceived affinity between the car and his

architecture. Similarly, since then, photographers have placed automobiles

adjacent to Modernist architecture to illustrate their interaction.

Between 1935 and 1936 , as part of a competition held by the

Societe des Ingenieurs de l’Automobile, Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre

Jeanneret designed a small affordable rear-engine three-seater car called the

Voiture Minimum. They went about the proposal like architects. First they drew

a plan, then sketched elevations and sections, and later they produced several

perspective views. They confirmed that their main aim was to assure the maximum

comfort of the passengers.

In 1932, Buckminster Fuller and the sculptor Isamu Nogachi,

inspired by nautical forms and bird flight, made a model for a streamlined 4D

Transport vehicle. This, along with the

Dymaxion House and 4D Auto-Airplane projects, was a precursor to the

three-wleeled rear-engine Dymaxion car produced with yacht designer W. Starling

Burgess in the years that followed, when Dymaxion cars #1, #2 and #3 were built

with advanced aerodynamic bodies.

Some of these architects’ designs contributed to the next

stages of automobile development: several manufacturers took up the Adler

couchettes arrangement; the Voiture Minimum project pointed the way towards

future proposals for small city autos; and Dymaxion cars promoted the use of

streamlining in automobile designs in the United States, starting with the

Crysler Airflow of 1934.

Architects’ attempts to bring beauty into their automobile

designs carried the process of building a machine to a higher order. In 1934,

the English art historian Herbert Read observed: ‘ the most unexpected objects

can acquire an abstract kind of beauty. The motor – car is the obvious

example.’3 Modernist architects aimed to integrate objects from the world of

machines and industry into the world of sculptural art. Their proposal were

infused with human soul and poetry to induce emotion and empathy, elevating

them above pure industrial design. Norman Foster has emphasized this element of

Modernist architecture, writing of the ‘ poetic, sentimental and deeply

spiritual dimension’ of Buckminster Fuller’s work.4

NOTES

1-Jacobus Johannes Pieter

Oud, ‘ Über die zukünftige Baukunst und ihre architektonischen

Möglichkeiten’, in Hollandische Architektur, Bauhausbücher 10, 2nd

ed. (Munich: Albert Langen Verlag, 1926), 13.

2-

Walter Dorwin Teague, Design This Day (London: The Studio,1946),66.

3-

Herbert Read, Art and Industry (London: Faber and Faber, 1934), 54

4-

Norman Foster, ‘Insights that Last Forever’, The Architects’ journal, London,

December 14, 1995.

https://tienda.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/motion-autos-art-architecture-catalogue

POPULARISING

This gallery

shows how attempts to produce a reliable and affordable modern “people’s car”

marked the next step in the evolution of the automobile. The process started in

the nineteen thirties with the deployment of national scale industries, often

with political overtones. After the second World War, during a period of

economic recovery and shortages, the automobile became a symbol of national

pride and regeneration.

Post war

austerity-imposed limitations of size, cost and availability of materials but

did not inhibit the creativity of designers – on the contrary they were spurs

to encourage innovation and ingenuity – to do more with less.

The art and

fashion of the period fused with the mass appeal of mobility. For example, the

Austin Mini and the mini skirt – Op Art and the logo by Victor Vasarely for

Renault. Displayed automobiles like the Beetle and the VW Microbus are examples

of how companies like Volkswagen have contributed to the democratization of the

automobile.

During this

period the proliferation of compact cars in Europe and their bigger relatives

in the United States magnified the imprint of the automobile on the urban and

rural landscape of both continents.

CHRISTO

Wrapped Volkswagen (Project for 1961 Volkswagen Beetle

Salon), 2013

(Project 1961)

Collage Graphic With Original Volkswagen Covered in Fabric

and HandOverpainting

Dimensions: 55.8 cm x 71 cm

Ed. Nr.: L/XC + 160 + 50 AP + 15 HC

Galerie Breckner

© Christo, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2022

LE CORBUSIER,

Voiture

Minumum, 1936

India Ink

Dimensions:

32 x 50 cm.

Fondation Le

Corbusier, Paris, France

© F.L.C. (VEGAP) 2022

HANS FEIBUSCH

Architects

Prefer Shell, 1933

Lithograph

Poster

Dimensions:

76 x 114 cm.

Courtest of

Shell Heritage Art Collection, United Kingdom

© Sotheby’s / Bridgeman

VW, TYPE 2

MICROBUS DELUXE 'SAMBA', 1962

Stiftung

AutoMuseum Volkswagen

© Volkswagen AG

CITROEN, 2CV

SAHARA, 1961

Foster Family

Collection

Photo © Nigel Young

THE GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM BILBAO

Outsıde the Museum

Surrounded by

attractive avenues and squares, the Museum is located in a newly developed area

of the city, leaving its industrial past behind. The Museum plaza and main

entrance lie in a direct line with Calle Iparragirre—one of the main streets

running diagonally through Bilbao—, extending the city center right up the

Museum's door. Once in the plaza, visitors access the Hall by making their way

down a broad stairway, an unusual feature that successfully overcomes the

height difference between the areas alongside the Nervión River, where the

Museum stands, and the higher city level. This way, Gehry created a spectacular

structure without it rising above the height of adjacent buildings. The highest

part of the Museum is crowned by a large skylight in the shape of a metal

flower covering the Atrium, one of the building's most characteristic features.

It is possible to walk

all the way around the Museum, admiring different configurations from each

perspective and also a number of artworks installed outside by artists such as

Louise Bourgeois, Eduardo Chillida, Yves Klein, Jeff Koons, or Fujiko Nakaya.

The Museum site is crossed at one end by La Salve Bridge that, since 2007,

supports the sculpture commissioned from Daniel Buren entitled Arcos rojos /

Arku Gorriak. Stretching under the

bridge, gallery 104—an enormous, column-free space that houses Richard Serra’s

installationThe Matter of Time—ends in a tower, a sculpture gesture that brings the

architectural design to a crescendo that appears to envelop the colossal bridge

and effectively incorporates it into the building.

Inside the Museum

Once inside the Hall,

visitors access the Atrium, the real heart of the Museum and one of the

signature traits of Frank Gehry's architectural design. With curved volumes and

large glass curtain walls that connect the inside and the outside, the Atrium

is an ample space flooded with light and covered by a great skylight. The three

levels of the building are organized around the Atrium and are connected by

means of curved walkways, titanium and glass elevators, and staircases. Also an

exhibition space, the Atrium functions as an axis for the 20 galleries, some

orthogonally shaped and with classical proportions and others with organic,

irregular lines. The play with different volumes and perspectives generates

indoor spaces where visitors do not feel overwhelmed. Such variety has

demonstrated its enormous versatility in the expert hands of curators and

exhibition designers who have found the ideal atmosphere to present both large

format works in contemporary mediums and smaller or more intimate shows.

In addition to the

gallery space and a separate office building, the Museum has a visitor

orientation room, Zero Espazioa; an auditorium seating 300; a store/bookstore;

a cafeteria; and two restaurants: a bistro and a one Michelin star haute

cuisine restaurant.

http://www.guggenheim-bilbao.es/en/the-building/inside-the-museum/

SPORTING

In the post war economic boom years of

the1950s and 60s the technical demands of competitive racing – particularly

Formula 1 – saw racing and road automotive design diverge further into separate

design disciplines. The market for fast sports cars expanded and drew on the

technology of their racing counterparts.

The five

examples selected are each in their own way a delight to behold, quite aside

from their racing pedigrees on roads and closed circuits. They merge art and

fashion to satisfy the fantasy of speed and adventure – glamorous and desirable

as objects of contemporary culture. The most emblematic examples became

powerful images on the big screen, emulating the Hollywood stars in their

degree of celebrity.

These

automobiles were portrayed as cult objects by artists and designers such as

Andy Warhol and Ken Adams. In his lifetime, Frank Lloyd Wright owned more than

eighty cars – many of which are classics and are featured in this exhibition.

His unbuilt project in 1925, for Gordon Strong, the “Automobile Objective”

shown here, was the first use of a central spiralling ramp which would later be

the central feature of his Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

GIOTTO BIZZARRINI

Ferrari 250 GTO, 1962

Ten Tenths

© Ben de Chair

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium (unbuilt)

Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland, 1924–25

Perspective

Coloured Pencil on Tracing Paper

Dimensions: 50.8 x 78.7 cm

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of

Modern

Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia

University, New York)

© 2022 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale,

Arizona

© Frank Lloyd Wright, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2022

LANCIA,

STRATOS ZERO, 1970

Philip

Sarofim Collection, United States

© Photograph by Michael Furman

FRANCO SCAGLIONE

Alfa Romeo BAT Car 7, 1954

Rob and Melanie Walton Collection

© Photograph by Michael Furman

VISIONARIES

Visionaries

starts in the mid-20th century when the stage was set for utopian vehicles, and

artists and designers explored radical new forms on the themes of speed and

motion. Many anticipated possibilities for the future of driving that were

decades ahead of their time. Automobiles inspired by the desire to go ever

faster pushed the limits of engine technology and aerodynamic forms, inspired

by the new technologies of turbine, jet, nuclear, and automation.

This space

celebrates a diverse range of visionary vehicles and their designers and

contemplates the beauty of their fluid forms and aerodynamic achievements.

These are exhibited alongside works from the Futurist Movement and its

obsession with motion and speed, notably Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of

Continuity in Space (1913), with its bronze robes flowing as if in a wind

tunnel.

There are

visual affinities between the futurist paintings of Giacomo Balla and the

one-off concept cars such as the three examples from General Motors—exhibited

here together for the first time in Europe— from the nineteen-fifties. This

period also saw depictions of driverless cars – a science fiction vision that

is close to the reality of today. The utopian vision of automobile design is

mirrored in the art and architecture of Eero Saarinen’s modernist masterpiece

the General Motors Technical Center – described as an “industrial Versailles”.

HARLEY EARL

General Motors, Firebirds I, II and III, 1954-1958

General Motors

General Motors / Photograph by Rodney Morr

ANDREAS GURSKY

F1 Pit Stop I (F1Boxenstopp I), 2007, from the series Pit

Stop

(Boxenstopp), 2007

Chromogenic Colour Print on Diasec

Dimensions: 178 × 497 cm

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France

© Andreas Gursky / Courtesy Sprüth Magers / VEGAP, 2022

Photo: © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

JOHN OWEN (LEAD DESIGNER)

Mercedes-AMG F1 W11 EQ Performance Formula One Racing Car,

2020

Mercedes-Benz Classic

© Mercedes‑Benz AG

UMBERTO BOCCIONI

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, (Forme Uniche Della Continuità

Nello Spazio), 1913, (cast 1972)

Bronze

Dimensions: 117,5 x 87,6 x 36,8 cm

Tate, Purchased 1972

© Tate

TULLIO CRALI

The Strength

of the Curve 1930

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions:

70 x 90 cm.

Associazione

Culturale FuturCrali – Private Collection

© Tullio Crali. Photo; Studio Closeup

R.

BUCKMINSTER FULLER

Inventions:

Twelve Around One, 1981

Screenprint

on Paper

Dimensions:

75.9 x 101.5 cm.

Norman Foster

Archive

© Courtesy The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

R. BUCKMINSTER FULLER

Dymaxion #4, 2010 (Based on #1-3, 1933-34)

Foster Family Collection

© Norman Foster Foundation

FAY S.

LINCOLN

Buckminster

Fuller’s Streamline Automobile Models, 1932

Photograph

Historical

Collections and Labor Archives, Eberly Family Special Collections Library,

Penn State University Libraries, United States

FAY S.

LINCOLN,

BUCKMINSTER

FULLER: DYMAXION TRANSPORT, 1933

Photograph

Historical

Collections and Labor Archives,

Eberly Family

Special Collection Library,

Penn State University Libraries, United States

EZRA STOLLER

General Motors Technical Center, 1956

Photograph

General Motors

GIACOMO BALLA

Abstract

Speed + Sound, 1913 – 1914

Oil on Board

Dimensions:

54.5 x 76.5 cm.

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice

( Solomon R.

Guggenheim Foundation, New York )

Italy. © Giacomo Balla, VEGAP, Bilbao

TULLIO CRALI

Destruction

Construction, 1932

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions:

66 x 48.5 cm.

Associazione

Culturale Futur Crali – Private Collection

© Tullio Crali

ANTON GIULIO

BRAGAGLIA

The Typist

1911

Gelatin

Silver Print

Dimensions:

11.9 x 16.7 cm.

Gilman

Collection, Gift of the Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

©Anton Giulio Bragaglia, VEGAP, Bilbao

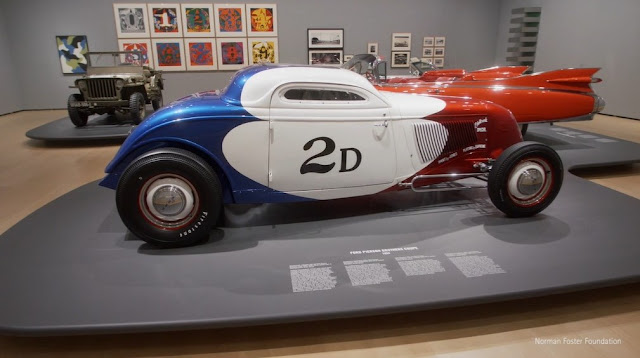

AMERICANA

Nowhere has

felt the impact of the automobile as fully as the United States. It has shaped

the American economy, landscape, urban and suburban spaces as well as popular

culture to a degree unseen anywhere else. It was the first country to feel the

benefits of mass ownership – and the first to have to confront the

environmental consequences of an auto-based society, with its energy consuming

commutes and social isolation.

The romance

of the road, the transcontinental trip across the “big country” and its endless

horizon, is emblematic of American culture with its enroute diners and filling

stations. The storied road trip has been the subject of photographs, paintings,

music, and literary tracts from the 1930’s new deal era through the present.

Here, we can view through the camera lens of Dorothea Lange, Marion Post

Wolcott, O. Winston Link, as well as the paintings of Ed Ruscha and Robert

Indiana. As a backdrop to the automobiles, we can experience the precision of a

sculpture by Donald Judd and compare it with the crushed relics of the

automobile in a work by John Chamberlain.

The range of

vehicles contrasts the extravagant tail fins of a giant luxury Sedan with a

typical muscle car next to a flamboyantly pained hot-rod and the stripped-down

utility of a wartime jeep

JEEP, WILLYS

MB, 1945

Foster Family

Collection

Photo © Nigel Young

ROBERT

INDIANA

Decade:

Autoportrait, 1960 – 1969

Serigraphs

Dimensions:

94 x 92 cm. approx. each. Ed. 41/50

Kasmin

Gallery, United States

© 2022 Morgan Art Foundation, VEGAP, Madrid

ROBERT

INDIANA

The Brooklyn

Bridge 1964

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions:

342.9 x 342.9 cm.

Detroit

Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase,

Mr. and Mrs.

Walter Buhl Ford, II Fund, United States

© 2022 Morgan Art Foundation, VEGAP, Madrid

FORD, PIERSON BROTHERS COUPE, 1934

EDWARD RUSCHA

Standard Station, 1966

7‑Color Screenprint

Dimensions: 65 x 101.6 cm

Artist proof Courtesy of the Artist © Ed Ruscha

JOHN

CHAMBERLAIN

Dolores

James, 1962

Welded and

Painted Steel

Dimensions:

184.2 x 257.8 x 117.5 cm.

Solomon R.

Guggenheim Museum, New York, United States 70.1925

© John

Chamberlain, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2022

Photo by Kristopher McKay

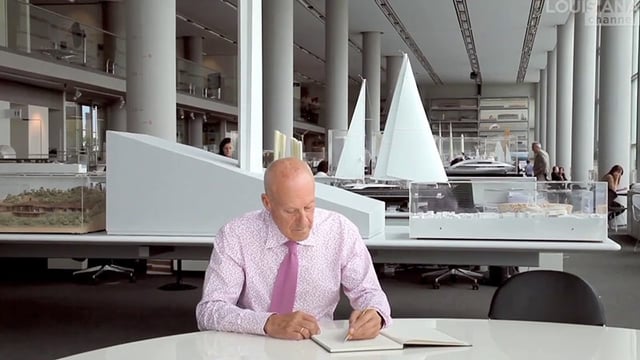

NORMAN FOSTER

I have long

been fascinated by the beauty of the machines of motion – from aircraft,

bicycles, automobiles and locomotives to ships, space vehicles and Zeppelins.

The most outstanding examples of these machines have an inherent beauty. They fire

my imagination in the same way that I am inspired by great works of

architecture, painting and sculpture. In my view, they have and artistic

dimension that derives from their capacity to move the viewer emotionally, to

spark visual delight or awe.

The best

automobile are, as curator Arthur Drexler memorably described them, like

‘rolling sculpture’ - their seductive form invite physical contact. I recall an

artist friend running his hand along the rear wing of my 1953 Bentley R Type

Continental and declaring that it was like stroking a work by Constantin

Brancusi or Henry Moore. That visual connection, once made, is incredibly

compelling.

This

exhibition has given me the opportunity to celebrate many such links between

these diverse creative worlds-you will, incidentally, find the Bentley and a

reclining figure by Moore juxtaposed in one of the galleries. Curating it has

given me a platform to protest the silo mentality that still prefers to

compartmentalize and academically protect the different disciplines, rather

than seeking to dissolve the barriers between them. It has also allowed me to

share some personal passions.

I chose the

words of the title - autos, art and architecture – carefully, mindful that

combining their disparate meanings might raise questions, or even be seen as

provocative. What, for example, does the concept of motion have to do with art

in the context of today? And what, if anything, do the artefacts of mobility –

at such vastly different scales – have in common with the separate worlds of

art and architecture?

This

exhibition starts with the birth of the automobile in the late nineteenth

century and moves on to celebrate the many different chapters and variants in

its life, including its gladiatorial role in competitive events. Woven through

these diverse stories are the themes of art and architecture. Stripped of its

function, the consciously sculpted automobile has a classic beauty and there is

another kind of aesthetic appeal in the raw edginess of the more utilitarian

vehicles, such as the military jeep.

However, the

automobile has inspired not only artists like Sonia Delaunay from the 1910s

onwards and more recently Edward Hopper and Ed Ruscha; it has also played a

pivotal role in the Futurist movement that originated in Italy in the early

twentieth century. Umberto Boccioni’s flowing figure of 1913, Unique Forms of

Continuity in Space (Forme uniche della continuita nello spazio), strides as if

in a wind tunnel, a structure that nearly two decades later would become an

essential tool in the development of streamlined form.

The father of

streamlining, Paul Jaray, designed airships and patented the first streamlined

cars. One model resulting from his wind tunnel studies bears an uncanny

resemblance to Brancusi’s Fish (Le Poisson) sculptures, such are the overlaps

between the fine arts and industrial design. The theme of interaction between

the arts and the automotive world permeates six of the exhibition’s seven

galleries.

Although the

automobile has the starring roe, the exhibition is far more than a celebration

of the aesthetic qualities of the automobile in isolation-worthy though that

would be. I link it to architecture because architecture is inseparable from

mobility - not just in terms of buildings, but also the infrastructure of

public spaces and the routes that define our cities and the highway that

connect them. More than any other machine, the automobile has transformed our

urban and rural landscapes. I connect it to art – in the form of painting,

sculpture, photography and the moving image – because art is simultaneously a

mirror of our society and a harbinger of change. This is aside from the use of

the word to describe the ‘art’ of architecture and the ‘art’ of the automobile.

It is easy to

imagine a show of cars, or an exhibition of paintings and sculptures, or one

devoted to the works of an architect. Less predictable is to mix these together

– indeed, I believe that this is the first time it has been done. So, where did

this idea originate, and why do I think it is important to try to show how

these separate domains are connected environmentally and artistically, and how

they might determine our future?

I need to go

back in time, and to begin with a disclaimer: as an invited curator, I have no

pretentions to scholarship in the fields of art or automotive history beyond

that of enjoying the contemplation of a painting, a work of sculpture or a

classic car. Professionally, I am an architect, driven passion-ately by the

design of buildings, and over time that passion has extended parallel to an

involvement in cities and their infrastructure. Starting when I was a student,

my interest ranged beyond buildings and into the routes, connections and public

spaces of towns and cities. In the creative process of designing, I also sensed

that there was a special bond between architecture and engineering that was

compromised by the traditional arm’s-length working relationship between these

professions. This led me to explore new ways of working with other skills,

particularly those of environmental and structural engineering. Consequently, I

know that the quality and performance of design, whether that of a building or

a city, is enhanced by the active participation of complementary disciplines.

The idea of mobility is one of the hallmarks of our era and is subject to upheavals as we try to combat global climate change and move from fossil fuels to clean energy. This is mirrored in the current shift of vehicular propulsion away from the gasoline-burning internal combustion engine to electric motors and hydrogen fuel. Somehow, the potential to create clean fuels for our existing technology seems to have been overlooked and this is touched on in the exhibition – for example, we highlight the possibility of greening Formula One to make it carbon free. Converting bio waste into fuel using clean energy is, again, carbon neutral, while the technology now also exists to produce aviation fuel from seawater – the latter having the added benefit of being climate restorative because it deacidifies the oceans. Then, alongside issues of propulsion, there is the growth of artificial intelligence and automation, with the prospect of robotics replacing the need for a driver or pilot. Beyond that, there is the rise of aerial mobility as we witness the rapidly evolving development of drones capable of carrying goods and people. In short mobility is moving away from evolution and could now be entering a period of revolution.

It has been

said that if you wish to look far into the future, then you must first look

back to the past. In other words, what are the lessons of history? It is worth

remembering that at the time of its birth, at the end of the nineteenth

century, the automobile was seen as the savior of the most populous

metropolitan centres, which at the time were London and New York. Mobility back

then was horse-drawn and these cities were engulfed in rising tides of horse

dung. The resulting flies, stench and disease had become unbearable. However,

in no time, the introduction of the automobile transformed cities for the

better – another form of congestion may have reigned, but the streets underfoot

were clean again.

Fast forward

a century or more and the automobile has been recast as the urban villain. It

is the equivalent of the massed horses in the past polluting cities, destroying

the quality of air, taking over the pedestrian domain and adding to the threat

to the environment. London has even taxed conventional cars out of its centre.

Many cities and towns around the world have introduced other kinds of

restriction. But the impending revolution in mobility could see a return, full

circle, to that period at the turn of the twentieth century before the electric

motor was supplanted by the internal combustion engine. Interestingly, in those

early days, more New York City taxis were powered by battery than by gasoline

and they too played a key role in rescuing the city from pollution.

It was not so

long ago that the vision of the future city was literally driven by the

automobile. Le Corbusier’s ‘ Plan Voisin for Paris ‘ of 1925, and his

subsequent proposals for the Ville Radieuse, anticipated the growth of highways

that would not only connect cities but would also constitute their urban heart.

We see Le

Corbusier’s urban vision made concrete in a city such as Brasilia, inaugurated

as the capital of Brazil in 1960. Brasilia was conceived by a distinguished

design team, orchestrated architecturally by Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa,

within a landscape setting by Roberto Burle Marx, and whatever its shortcomings

as a place to live and work, it has an undoubted grandeur. The same cannot be

said for its smaller-scale equivalents, such as the strip malls that have grown

up ad-hoc on the edges of highways across the United States.

If an alien

species were to approach our planet from outer space and observe its surface

from afar, they might conclude that life on Earth was metallic and vehicular,

such is the physical imprint of the automobile on the landscape. Urbanity and

mobility have moved hand in hand in transforming the natural habitat.

For a period

in its history, the automobile was the prerogative of a wealthy minority before

waves of democratization moved towards a leveling of society, reflected in turn

by the availability of cars for the masses. The automobile became symbolic of

progress and the good life, often with political undertones. In its golden age in the

United States more than half a century ago, the automobile was an undoubted

status symbol. There was an optimism about the future, and concept cars in the

1950s anticipated a driverless tomorrow where the motorway commute would become

a time for family leisure and entertainment.

Today pride

of ownership in younger generations is not what it used to be; instead there is

an appetite for ride-sharing and on-demand services such as Uber, fuelled by

the rise of hand-held communication devices. Manufacturers of automobiles and

aircraft alike see themselves more in the mobility business and less in the

business of creating products for customers.

Predictions

for the future abound. Add changing patterns in the work-place to the trends

already noted and one might imagine a time not too far away when fewer vehicles

earthbound and aerial, move continuously, platooning nose-to-tail, safety and

densely moving people and goods alike.

The final

gallery in the exhibition is, appropriately, devoted to visions of the future

as seen by an emerging generation of students. This future is loosely

interpreted as the end of the twenty-first century, therefore coinciding with

the two-hundredth anniversary of the first automobile. Sixteen schools of

design and architecture from around the world have contributed their visions,

some working independently and others in collaboration with industry.

This

exhibition has been produced by the Norman Foster Foundation in collaboration with

the Guggenheim museum Bilbao team. The Foundation’s mission, through its

education and research programmes and its archive, is to help younger

generations to anticipate the future by breaking down the barriers between

different disciplines. This exhibition is entirely in that spirit but like the

Foundation itself it aims to raise the interest and curiosity of a far wider

audience-here at the Guggenheim Bilbao, that is anyone who is interested in

automobiles, art and architecture.

https://tienda.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/motion-autos-art-architecture-catalogue

.png)

.jpg)