HELEN FRANKENTHALER: PAINTING WITHOUT RULES AT PALAZZO STROZZI FLORENCE

H

HELEN FRANKENTHALER:

PAINTING WITHOUT RULES AT FLORENCE PALAZZO STROZZI

September 27, 2024 –

January 26, 2025

Palazzo Strozzi

celebrates Helen Frankenthaler's revolutionary art with the largest exhibition

ever held in Italy, organized with the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, which

places her works in dialogue with contemporary artists such as Jackson Pollock,

Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Anne Truitt.

From September 27, 2024,

to January 26, 2025, Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi presents Helen Frankenthaler:

Painting Without Rules, a major exhibition celebrating one of the most

significant artists of the 20th century. Frankenthaler’s revolutionary approach

to painting is explored through works produced between 1953 and 2002, in

dialogue with paintings and sculptures by contemporary artists, including

Jackson Pollock, Morris Louis, Robert Motherwell, Kenneth Noland, Mark Rothko,

David Smith, Anthony Caro, and Anne Truitt.

Organized by Fondazione

Palazzo Strozzi and Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, and curated by Douglas

Dreishpoon, Director of the Helen Frankenthaler Catalogue Raisonné, the

exhibition aims to highlight the artist's innovative practice through the lens

of the artistic affinities, influences, and friendships that marked her

personal and artistic life.

Through large canvases

and sculptures by Frankenthaler and numerous works by other artists, the

project stands as one of the most important exhibitions ever dedicated to the

artist in Europe and the most comprehensive survey of her work to date in

Italy. Loans come from the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation in New York and

renowned international museums and collections, including the Metropolitan

Museum of Art in New York, Tate Modern in London, Buffalo AKG Art Museum,

National Gallery of Art in Washington, ASOM Collection, and the Levett

Collection, as well as Helen Frankenthaler’s own personal collection.

With her innovative

soak-stain technique, Frankenthaler indelibly marked the evolution of modern

painting, establishing a new relationship between color, space, and form. The

technique involved applying diluted paint horizontally on untreated canvases,

creating effects similar to watercolor but with oil paints on a large scale.

Frankenthaler applied paint with brushes or sponges, or directly from buckets,

allowing it to spread and blend naturally, creating unique chromatic

interactions marked by blurred transitions and translucent overlays.

Helen Frankenthaler:

Painting Without Rules celebrates an artist who challenged conventions and

expanded the boundaries of painting with a bold and intuitive vision that broke

traditional norms. Frankenthaler is distinguished by her unique ability to

combine abstraction and poetry, technique and imagination, control and

improvisation, expanding her practice beyond established canons in search of a

new freedom in painting.

Arturo Galansino,

Director General of Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, states, “We are thrilled to

bring Helen Frankenthaler’s work to Italy at an unprecedented scale,

introducing new audiences to one of the greatest American artists of the

twentieth century. With her innovative and no-rules approach, Frankenthaler stood

out as a pioneering figure in the field of abstract painting, expanding the

potential of the genre in ways that continue to inspire artists today.”

“Helen Frankenthaler’s

dedication to painting was enriched by her friendships with artists, some of

whom became part of her extended family,” remarks Douglas Dreishpoon.

“Frankenthaler’s artistic circle was like an ecosystem of creative forces in

constant play. Seeing their work in close company enables us to better

understand Frankenthaler’s own innovations.”

Born in New York City,

Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) studied studio art and art history with Paul

Feeley at Bennington College, before returning to Manhattan, where she

gravitated to abstract art. By the early 1950s she had gained direct access to

the New York School and key figures in postwar American art, some of whom

became part of her social circle. Frankenthaler surrounded herself early on

with kindred artists who shared her unwavering commitment to experimentation.

With trusted friends she shared studio visits, ongoing correspondence, and

poignant perspectives on life. She also collected friends’ work, which was

prominently displayed in her Manhattan home. Among them, Helen’s Collage, 1957,

a paper collage by Robert Motherwell; Aleph Series V, 1960, a painting by

Morris Louis; and Ascending the Stairs, 1979-83, a sculpture by Anthony Caro,

will all be on view in Painting Without Rules.

Organized

chronologically, the exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi tracks the development of

Frankenthaler’s creative practice over six decades, with each room dedicated to

a decade from the 1950s to the 2000s. Frankenthaler’s artistic innovations,

seen in tandem with contemporaneous paintings, sculptures, and works on paper

by friends, sheds light on the synergies and affinities between these artists.

The exhibition

demonstrates the well-established influence of Jackson Pollock on Frankenthaler

in the 1950s. Pollock’s Number 14, 1951, an abstract black and white enamel

painting that hints at subliminal imagery, is shown alongside Frankenthaler’s

Mediterranean Thoughts, 1960, a colorful oil painting with similar “elements of

realism abstracted or Surrealism”—a phrase Frankenthaler used to describe

Pollock’s work after seeing it in person in 1951. Viewers will be invited to make

visual connections between subsequent works and their affinities. For instance,

Frankenthaler’s Tutti-Frutti, 1966, a buoyant painting of colored clouds

created using her innovative soak-stain technique, finds a Euclidean analog in

David Smith’s Untitled, 1964, a painted steel sculpture constructed of

geometric shapes stacked one on top of another, all coasting on four small

wheels. Frankenthaler’s own sculptures are also included in the exhibition.

Heart of London Map, 1972, a steel assemblage, bears an affinity to Anthony

Caro’s Ascending the Stairs, 1979-83, in its piece-by-piece construction.

Frankenthaler’s works from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s are a testament to an

artist who never stopped breaking the rules to explore new ways to make art.

The exhibition is augmented with educational projects that will provide visitors access to Frankenthaler’s life, her artistic practice and community. Further, a rich and articulated public program will offer activities for schools, families, young people and adults, with a particular attention to accessibility and engagement.

GALLERY 1

The exhibition opens with four works from the 1970s, a period when Helen Frankenthaler was perfecting her soak-stain technique, developed in 1952. A painting like Moveable Blues howcases the artist in peak form: pouring, painting, and drawing with absolute confidence. The lessons she learned from Jackson Pollock in the early 1950s—that it was possible to paint using various materials and tools while circling a large canvas spread out on the floor—inspired another type of abstract painting with expansive fields of color, known as Color Field painting. Fiesta and Untitled show how similar ideas explored in a smaller format share the same tonal atmosphere, spatial complexity, and linear articulation as Moveable Blue. Other works in this exhibition present the achievements the artist reached during this decade. Matisse Table is one of the ten sculptures Frankenthaler created in the London studio of her friend Anthony Caro in 1972. Frankenthaler had a deep appreciation for sculpture and sculptors, especially Caro, David Smith, and Anne Truitt, whose works she owned and kept close by. Many of the sculptures created during Frankenthaler’s two-week stay in Caro’s studio pay homage to Smith, who early on had encouraged her to create three-dimensional works. It is not only the materials used, some of which came from Smith’s studio, that honor him, but also the way they were cut, welded, and composed. Frankenthaler approached sculpture with the same intuitive impulses she channeled to paint. Matisse Table, with its tilted surface, fan-like shapes, and still life elements, refers to Henri Matisse’s painting Pineapple (1948), transforming the original model into something new.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Matisse Table

1972

Steel

Dimensions:

209.6 × 134.6 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Helen Frankenthaler on

Matisse Table:

“I made this in London

when I worked at the sculptor Anthony Caro’s studio one summer [in 1972] and

made ten metal sculptures . . . a few years later, he came to my studio in New

York and painted.” —Palm Springs lecture transcript, 1996.

“I had been staring at a

Matisse [painting] called Pineapple from ’48 [reproduced on a large poster in

Caro’s studio] . . ., and thought, could that in any way be translated into a

sculpture?” —AIC lecture transcript, 1991.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Moveable Blue

1973

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

177.8 × 617.8 cm

ASOM

Collection, inv. E 809

© 2023 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Moveable Blue 1973 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Fiesta 1973

Acrylic on

Paper

Dimensions:

56.5 × 76.8 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Fiesta 1973 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Untitled 1973

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

51.4 × 85.7 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

GALLERY 2

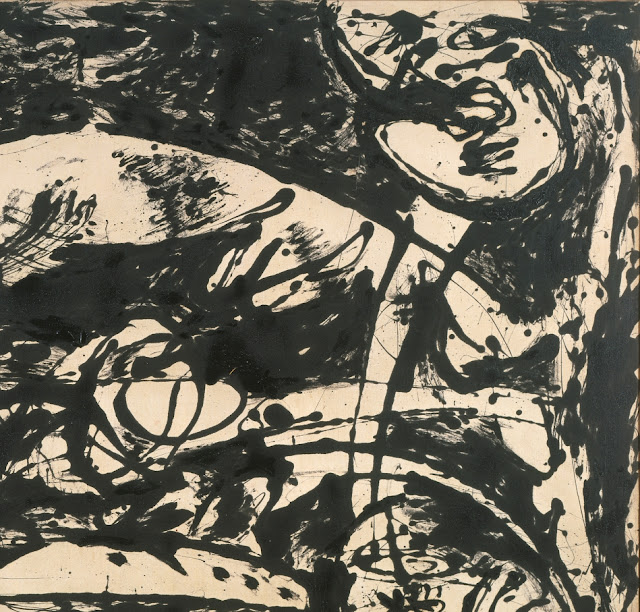

Frankenthaler was living a bohemian life in downtown New York City when she saw Jackson Pollock’s Number 14 in a solo exhibition of his black-and-white paintings at the Betty Parsons Gallery. The work had a profound impact on the young painter who, while visiting Pollock on Long Island, saw his rustic studio barn and witnessed his painting process. Pollock maneuvered around monumental canvases rolled on the studio floor. As abstract as Number 14 appears, tell-tale images emerge. The suggestion of subliminal imagery intrigued Frankenthaler, who responded to Pollock’s radical methods: the choreography of an improvised full-bodied gesture—“ropey skeins of enamel, webbing, working from the shoulder not the wrist”—and the possibility that abstract painting could have some kind of “message.” Abstraction, born from spontaneous drawing, allowed Frankenthaler to express her imagination with pictorial signs, symbols, and evocative “scenes” without fully revealing herself. Ambiguity is essential for her images to remain mysterious—like poems,—to mean different things to different people. Pollock enabled her to see painting as an intuitive process primed by drawing: an approach without limits that inspired Frankenthaler’s masterpiece, Mountains and Sea, as well as many of the paintings in this exhibition, including those in this room, which indicate a precocious artist of prodigious talent.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Mediterranean

Thoughts 1960

Oil on Sized,

Primed Canvas

Dimensions:

256.5 x 237.5 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Mediterranean Thoughts 1960 (Detail)

JACKSON

POLLOCK

No. 14 1951

Enamel on

Canvas

Dimensions:

149.3 × 269.5 cm

Londra, Tate.

Purchased with assistance from the

American

Fellows of the Tate Gallery Foundation, 1988.

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Tate.

Helen Frankenthaler on

Jackson Pollock’s Number 14:

“[Pollock’s Number 14]

was more than just the drawing, webbing, weaving, dripping of a stick held in

enamel, more than just the rhythm. It seemed to have much more complication and

order of a kind that at the time I responded to. Something . . . more baroque,

more drawn and with some elements of realism abstracted or Surrealism or a hint

of it . . . It is a totally abstract picture, but it had that additional

quality . . . for me.” —Interview by Barbara Rose, 1968

JACKSON POLLOCK

No. 14 1951 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Western Dream

1957

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions:

177.8 × 218.4 cm

New York, The

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of the

Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, 2023 (2023.560)

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Western Dream 1957 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Open Wall

1953

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions:

136.5 × 332.7 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Helen Frankenthaler on

Open Wall: “[The painting began as] an experiment to create some kind of sense

of space and boundary. . . In the end, a spine of the painting, what makes one

respond, has very little to do with the subject matter per se but rather the

interplay of spaces and juxtapositions of forms.”

—Interview by Julia

Brown, After Mountains and Sea exh. cat., 1998.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Open Wall 1953 (Detail)

GALLERY 3

To see a painted steel sculpture by David Smith and a painted wood column by Anne Truitt, both from the 1960s, in the same room as four Frankenthaler canvases from the same period, is to appreciate why Frankenthaler developed close friendships with both sculptors. If the weightless clouds in Tutti-Frutti pulse with buoyant abandon, the rectilinear banners in The Human Edge descend monolithically. Frankenthaler and Smith shared a common belief when it came to making art: No rules! It didn’t matter whether you were a painter or a sculptor (or both), the message was the same: no rules meant never being complacent about how your art got made, what materials were used, or what the results might look like. Being open to surprise, even if it meant failing, was part of the creative process. So was constantly pressing against the limits of what had already been done to express yourself anew. Smith’s Untitled (Zig VI), constructed out of heavy girder beams stacked, welded, and coasting on miniature wheels, like a child’s monumental toy, is joyful. Truitt’s Seed gains personality through its painted surfaces. Frankenthaler and Truitt shared close friends, life experiences, and a mutual commitment to painting, something that Truitt—like Smith—did independently and in tandem with her sculpture.

DAVID SMITH

Untitled (Zig

VI) 1964

Steel, Paint

Dimensions: 200.3

× 112.7 × 73.7 cm

New York, The Estate of David Smith

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Alassio 1960

Oil on Linen

Dimensions:

216.5 × 332.7 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“I had to develop my own

technique, but I think technique determines aesthetic as much as one's

aesthetic determines a new medium. The making of them, controlling them, and

the surprise from them is a gesture that I do best, feeling that the edges can

spread and that I can manipulate the paint and the sides in relation to top,

bottom, drawing, spilling, staining, tinting, with much more reach and fewer

limits.”

Helen Frankenthaler

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Alassio 1960 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Cape

(Provincetown) 1964

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions: 278.5

x 237.2 cm

Melbourne,

National Gallery of Victoria. Purchased With the Assistance of

the National Gallery Society of Victoria, 1967, inv. 1773-5

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Tutti-Frutti 1966

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

297.18 × 175.42 cm

Buffalo, New

York, Buffalo AKG Art Museum.

Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr. 1976, K1976:8

“I believe in tradition.

In my case, my basic training–my heritage–was through Cézanne, the analytic

Cubism of Picasso and Braque, Kandinsky, Miró, Gorky, Pollock and many of their

peers, mentors, and satellites. I learned how to appreciate the Old Masters,

the Quattrocento, the Renaissance, along with the work of my contemporaries.

Sometimes for an artist, I think the aesthetic developments sneak in almost

without notice, a subtle urgency, an unconsciously programmed surprise. There’s

a natural order.”

Helen Frankenthaler

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Tutti-Frutti 1966 (Detail)

ANNE TRUITT

Seed 1969

Acrylic on

Wood

Dimensions: 217.2

× 45.7 × 45.7 cm

Baltimore,

Baltimore Museum of Art. Gift of Katharine Graham,

Washington, D.C., BMA 1995.121

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

The Human

Edge 1967

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

315 x 236.9 cm

Syracuse, NY,

Everson Museum of Art, Museum Purchase to Honor Director,

Max Sullivan

on the opening of the IM Pei building, 68.23

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Helen Frankenthaler on

The Human Edge:

“[The Human Edge] was

painted around the time of the debut of severe minimalist painting. At the

bottom edge, it’s a very personal, worried, non-geometric, non-clean

line—L-shaped. When it came time to title [the painting] . . . I [knew that I]

would call it The Human Edge because there was a lot about Minimalism that

removed the human quality—the human edge.”

—Palm Springs lecture

transcript, 1996..

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

The Human Edge 1967 (Detail)

GALLERY 4

The works by other artists displayed in this gallery, and in the two smaller adjacent rooms, provide a deeper understanding of Frankenthaler’s artistic circle. Some works came to Frankenthaler as gifts, tokens of friendship. Others were purchased by the artist. Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis saw Frankenthaler’s Mountains and Sea at her studio six months after it was painted. Compared to Pollock’s dense abstractions, Frankenthaler’s lightly stained canvas, full of light and space, offered an alternative approach that set American art on a new course. Frankenthaler and Robert Motherwell were married for thirteen years (1958–71). During this time, they shared family and friends, spent summers on Cape Cod and in Europe, and exchanged artistic ideas. Separated in age by fourteen years and temperamentally different (Frankenthaler extroverted, gregarious, and impish; Motherwell inherently shy, bookish, and introverted), both lived to paint. Motherwell’s Summertime in Italy and Frankenthaler’s Alassio (in previous gallery) allude to the summer of 1960, when the couple rented a villa in that seaside town. Inspired by each other’s company, the sun and the surf, both paintings radiate joie de vivre. Mark and Mell Rothko were also part of the couple’s artistic circle. What Pollock was to Frankenthaler in the 1950s, Rothko was in the early 1960s: the catalyst for another kind of abstract image. Frankenthaler’s Cape (Provincetown), in the previous gallery, has a distinct affinity to the Rothko in this gallery. Both artists render geometric form in ways that elevate its human qualities.

MARK ROTHKO

Untitled 1949

Oil and Mixed

Media on Canvas

Dimensions:

228.9 × 112 cm

Washington,

D.C., National Gallery of Art ©1998 Kate Rothko Prizel

and Christopher Rothko / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

MORRIS LOUIS

Aleph Series

V 1960

Magna on

Canvas

Dimensions:

266.7 × 208.3 cm

New York,

Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

© Maryland

College Institute of Art (MICA) /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

MORRIS LOUIS

Aleph Series V 1960 (Detail)

ROBERT

MOTHERWELL

Summertime in

Italy 1960

Oil and

Graphite on Paper

Dimensions:

148.4 × 107.9 cm

Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art. The Nancy Lee and Perry Bass Fund,

1999.55.4 © Dedalus Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

ROBERT MOTHERWELL

Summertime in Italy 1960 (Detail)

ROBERT MOTHERWELL & HELEN FRANKENTHALER

GALLERY 5

In the early 1950s,

Frankenthaler made the first of many visits to David Smith’s home and studio in

the Adirondack mountains near Lake George, a 352-kilometer drive north of New

York City. Bolton Landing was like another world, one where clouds hung off

totemic steel sculptures spread across open fields. Inside Smith’s cinderblock

studio, one would sense a space full of potential, a creative struggle with

heavy metals cast and welded.

The sculpture featured in

this room is a personage—prehistoric, gladiatorial, threatening. Portrait of

the Eagle’s Keeper was one of Frankenthaler earliest art acquisitions,

something she kept close by always. As she moved, the sculpture moved with her,

eventually occupying a prominent place in the Upper East Side townhouse she

shared with Robert Motherwell. There, it joined Mountains and Sea, Motherwell’s

Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 70 (1961), Rothko’s Untitled (1949, a gift to

Motherwell) and other cherished works by contemporaries and old masters.

DAVID SMITH

Portrait of

the Eagle’s Keeper 1948–49

Steel, Bronze

Dimensions: 96.5

x 32.7 × 57.8 cm

New York, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

FONDAZIONE PALAZZO

STROZZI

A Laboratory For Art,

Culture and Innovation

A dynamic cultural centre

of international importance offering a high quality exhibition and public

programme within a masterpiece of Renaissance architecture, Palazzo Strozzi is

a focal point of Italy’s cultural scene. Built around the original Renaissance

courtyard, a public square that plays host to concerts, performances,

installations and interventions and sees more than two million people pass

through it every year, Palazzo Strozzi’s is a key cultural hub in the city and

an important link between Florence and world.

The first example of an

independent public-private cultural foundation in Italy, the Fondazione Palazzo

Strozzi has been responsible for the Palazzo’s programme since its inception in

2006, organising more than 50 exhibitions and attracting in excess of three

million visitors to date. Creating a lively dialogue between the old and the

new, Palazzo Strozzi’s exhibitions range from critically acclaimed historical

surveys of old masters such as Pontormo & Rosso Fiorentino or Verrocchio, master of Leonardo, to

exhibitions with leading contemporary artists including Ai Weiwei, Carsten Höller and Marina Abramović. The unique mix of the

historical setting and contemporary programme makes Palazzo Strozzi an active

workshop for the new in Florence: new works of art by important artists; major

historical surveys and restoration campaigns leading to studies and

discoveries; important public debates on contemporary issues that forge new

ways of communicating about art and culture.

Whilst dedicated to

presenting new work and challenging ideas, the Fondazione aims to make the

programme as accessible and inclusive as possible, experimenting with new forms

of collaboration and audience engagement. The rich public programme based on

research into arts education includes specific offers for young people, schools

and families, as well as special audiences including visitors suffering from

Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and autism.

https://www.palazzostrozzi.org/en/palazzo-strozzi-foundation/

GALLERY 6

Frankenthaler met David Smith through the American critic Clement Greenberg. After she married Robert Motherwell in 1958, Smith became a beloved member of the family. All three artists, frequently joined by their young children, spent time together in New York City, at Bolton Landing, and on Cape Cod during the summer months. Smith’s untimely death in the spring of 1965 was a profound loss. The smaller works in this gallery, all gifts to Frankenthaler, are a tribute to love and friendship. Smith’s Untitled tabletop sculpture is a rumble-tumble free-for-all animated by the same orgiastic energy as Frankenthaler’s Tutti-Frutti. Two untitled works on paper, among the hundreds of figurative brush drawings that Smith made during the 1950s, attest to a sculptural imagination free of rules. Motherwell made Helen’s Collage a year before he and Frankenthaler were married. At Five in the Afternoon, Motherwell’s first “Elegy” painting, is titled after Federico García Lorca’s poem about the death of a bullfighter. Black on White No. 4, a single geometric figure suspended in space, signals the painter’s transition to related figures, open and closed.

ROBERT

MOTHERWELL

Helen’s

Collage 1957

Oil, Pasted

Papers, and Charcoal on Paperboard

Dimensions: 74.9

× 49.5 cm

New York, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

ROBERT

MOTHERWELL

At Five in

the Afternoon 1948–49

Casein and

Graphite on Paperboard

Dimensions: 38.1

× 50.8 cm

New York, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

GALLERY 7

During the early 1970s, following her divorce from Motherwell, Frankenthaler reinvented herself. Summers became a time for travel—to Italy, France, Switzerland, Austria, Belgium, and England. She leased a waterfront home with a studio in Stamford, Connecticut, and spent more time outside of New York City. Eventually, she purchased a home nearby on Shippan Point and built a new studio there. Some of the paintings from this period reflect this serene setting. Others portend another side of the painter’s personality—liberated, tough, provocative. From her living room, Frankenthaler had a clear view of Long Island Sound. Being near the water, as she had been for many summers in Provincetown with Motherwell, was comforting. Seascapes joined landscapes as the basis for new abstract paintings—tonal and atmospheric. As monochromatically uniform as Ocean Drive West #1 appears, awash in cerulean blue, thin passages of white offset by prismatic lines activate the surface. A series of “strip” paintings from the mid-1970s evoke the vertical assent of an urban setting. The directional white bands that bookend Plexus open the surface like vents. These also compress the painting’s center—clouds of delicately sponged and brushed color. Frankenthaler’s strips hum with the same erratic energy as the banners in The Human Edge. Mornings is one of a flurry of images resembling geologic formations or somatic cavities. Strokes of black and red marker, like errant jabs, dart across oceanic white foam.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Heart of

London Map 1972

Steel

Dimensions:

221 × 63.5 × 209.6 cm

The Levett

Collection, inv. CL 1026 © 2024 Helen Frankenthaler

Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Ocean Drive

West #1 1974

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

238.8 × 365.8 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Helen Frankenthaler on

Ocean Drive West #1:

“[The painting] was done

there [at Frankenthaler’s studio on Ocean Drive West, Shippan Point, Stamford,

Connecticut] . . .On Ocean Drive West you are always staring at horizon lines…

There are hazed-out parts of Long Island across the Sound, parts of it can be

visible, [other] parts not. I wasn’t looking at nature or seascape but at the

drawing within nature—just as the sun or moon might be about circles or light

and dark.”

—HF in Frankenthaler: A

Paintings Retrospective, 1989.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Ocean Drive West #1 1974 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Plexus 1976

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

289.6 x 228.6 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Mornings 1971

Acrylic and

Marker on Canvas

Dimensions:

294.6 × 185.4 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Mornings 1971 (Detail)

“Beautiful painting

relies in large part on drawing with color. In a way, drawing is the secret of

color because color that doesn’t work in space is meaningless decoration.”

Helen Frankenthaler

GALLERY 8

Entering middle age is a rite of passage for anyone. For Frankenthaler crossing the midlife threshold meant confronting new realities. She knew that maintaining a presence in New York to see others’ art and to conduct business was important. She also knew that spending more time away from the city, close to the water, was not only calming but essential. It was a question of balance. She found ways to have both, painting all the while.

Frankenthaler’s respect for the history of art, nurtured early on in Paul Feeley’s classes at Bennington College, never ceased. From Paleolithic caves to Monet’s water lilies, she drew from art of the ages, and during the late 1970s and 1980s, found renewed inspiration in paintings by Titian, Velasquez, Manet, and Rembrandt. Scrutinizing abstract details in old master paintings enabled Frankenthaler to cross a technical threshold into a tonal world of diaphanous veils, tinted grounds, subtle washes, and transparencies. She discovered another kind of space and light and brought these to bear in works like Eastern Light, Cathedral, Madrid, and Star Gazing. Anthony Caro entered Frankenthaler’s social arena in 1959, on his first trip to New York, and from then on remained one of her closest friends. It is a fitting tribute to see Caro’s Ascending the Stairs in the same gallery as Frankenthaler’s Yard. Caro’s sculpture, completed after he and Frankenthaler attended a David Smith symposium at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., evolved piece by piece, weld by weld, in much the same way that Frankenthaler’s Yard did. Both shared with Smith an empirical constructive approach that played out in real time.

ANTHONY CARO

Ascending the

Stairs 1979–83

Steel, Sheet,

Varnish

Dimensions:

111.8 × 83.8 × 101.6 cm

New York,

Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Eastern Light

1982

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

175.3 × 301 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Eastern Light 1982 (Detail)

“I think that once who

has had the training and limits, in my case anyway of cubism, and you stretch

out from that, instead of going further and further in, you are going further

and further out, up, down, surface. Which doesn't mean that you give up depth

and perspective, but that you are going out of the border and staying in and on

the picture plane.”

Helen Frankenthaler

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Madrid 1984

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

162.2 × 295.9 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Madrid 1984 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Star Gazing

1989

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

181.6 × 365.8 cm

2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Star Gazing 1989 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Cathedral

1982

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

179.4 × 304.8 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Cathedral 1982 (Detail)

GALLERY 9

By the 1990s Frankenthaler painted in two ways. One might coalesce all at once in a single session, with only minor additions—the breakthrough initiated decades earlier by Mountains and Sea. The other mode— what she called the “redeemed picture”—bore a more “worked-into or scrubbed surface, often darker, more dense.” The desired result, regardless of approach, was, a “beautiful picture” that looked like it had been “born at once, regardless of how many hours, or weeks, or years it took to make it.” Frankenthaler never questioned why she painted or for whom. Expressing herself through art was something she had done since childhood. Making art channeled her emotional energy and kept her focused and stable. Janus and Yin Yang commune like brother and sister. Sites for the confluence of opposites, both paintings share tinted grounds, layered surfaces, and transparent vectors. Some passages, rimmed with trails of fire or splattered with a spew of black dots, feel like thresholds to other galaxies, not unlike Star Gazing (in previous Gallery). The Rake’s Progress and Fantasy Garden display a dense physicality, because the painter was experimenting with gel medium mixed with acrylic and manipulated with rakes, masonry trowels, spatulas, sponges, and wooden spoons. The energized surfaces of Borrowed Dream and Maelstrom (both in the next Gallery)—tough, edgy, recalcitrant—raise existential questions about the artist’s late work.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Fantasy

Garden 1992

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

242.6 × 179.1 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Fantasy Garden 1992 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Yin Yang 1990

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

146 × 284.5 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Yin Yang 1990 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Janus 1990

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

144.8 × 240.7 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Janus 1990 (Detail)

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Janus 1990 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

The Rake’s

Progress 1991

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

240 × 174 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

The Rake’s Progress 1991 (Detail)

GALLERY 10

Frankenthaler had always shifted seamlessly between painting on canvas and paper. Paper provided an alternative to canvas, one that was easier to manipulate and, if need be, discard. The dialogue between paper and canvas was also age contingent: when working on the floor became too physically demanding, the artist used large sheets of paper or canvas placed on flat surfaces elevated on sawhorses. The paintings on paper that followed Frankenthaler’s marriage to Stephen DuBrul in 1994 seem to celebrate a new lease on life, while honoring past relationships. Optimism, buoyed by calligraphic clarity, characterizes Solar Imp and Cassis—each of which incorporates colored rectangles stamped onto the paper with a wide sponge. In Solar Imp, the rectangles appear below two black forms, recalling figures that appear in numerous paintings and works on paper by Frankenthaler and Motherwell during their marriage. Frankenthaler never wavered in her dedication to beauty, even when other younger, more politically engaged artists dismissed it as “obsolete, meaningless.” Frankenthaler’s vision of beauty embodied the human condition. Some of her most poignant late works, like Southern Exposure, feel like veils of time fleeting. Looking at Driving East, one might glimpse finality. Is the flickering light along the horizon ascending or descending? There’s every reason to be philosophical about growing old. “Over time, we’re left with the best,” was how Frankenthaler summed up her pursuit of an art unencumbered by rules. Given a life fully lived, there was no reason to believe otherwise.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Solar Imp

1995

Acrylic on

Paper

Dimensions:

198.1 × 151.8 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Solar Imp 1995 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Cassis 1995

Acrylic on

Paper

Dimensions:

154.3 × 198.8 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Maelstrom

1992

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

118.1 × 273.1 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Maelstrom 1992 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Driving East

2002

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

132.4 × 207 cm

Toronto, Audrey and David Mirvish

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Borrowed

Dream 1992

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

214.6 × 275.6 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER

Borrowed Dream 1992 (Detail)

HELEN

FRANKENTHALER

Southern

Exposure 2002

Acrylic on

Paper

Dimensions:

153.7 × 187.6 cm

© 2024 Helen

Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

HELEN FRANKENTHALER, A

BRIEF BIOGRAPHY

Helen Frankenthaler

(1928-2011), whose career spanned six decades, has long been recognized as one

of the great American artists of the twentieth century. She was eminent among

the second generation of postwar American abstract painters and is widely

credited for playing a pivotal role in the transition from Abstract

Expressionism to Color Field painting. Through her invention of the soak-stain

technique, she expanded the possibilities of abstract painting, while at times

referencing figuration and landscape in unique ways. She produced a body of

work whose impact on contemporary art has been profound and continues to grow.

Frankenthaler was born on

December 12, 1928, and raised in New York City. She attended the Dalton School,

where she received her earliest art instruction from Rufino Tamayo. In 1949 she

graduated from Bennington College, Vermont, where she was a student of Paul

Feeley. She later studied briefly with Hans Hofmann.

Frankenthaler’s

professional exhibition career began in 1950, when Adolph Gottlieb selected her

painting Beach (1950) for inclusion in the exhibition

titled Fifteen Unknowns: Selected by Artists of the Kootz Gallery. Her

first solo exhibition was presented in 1951, at New York’s Tibor de Nagy

Gallery, and that year she was also included in the landmark

exhibition 9th St. Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture.

In 1952 Frankenthaler

created Mountains and Sea, a breakthrough painting of American abstraction

for which she poured thinned paint directly onto raw, unprimed canvas laid on

the studio floor, working from all sides to create floating fields of translucent

color. Mountains and Sea was immediately influential for the artists

who formed the Color Field school of painting, notable among them Morris Louis

and Kenneth Noland.

As early as 1959,

Frankenthaler began to be a regular presence in major international

exhibitions. She won first prize at the Premiere Biennale de Paris that year,

and in 1966 she represented the United States in the 33rd Venice Biennale,

alongside Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, and Jules Olitski. She had her

first major museum exhibition in 1960, at New York’s Jewish Museum, and her

second, in 1969, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, followed by an

international tour.

Frankenthaler

experimented tirelessly throughout her long career. In addition to producing

unique paintings on canvas and paper, she worked in a wide range of media,

including ceramics, sculpture, tapestry, and especially printmaking. Hers was a

significant voice in the mid-century “print renaissance” among American

abstract painters, and she is particularly renowned for her woodcuts. She

continued working productively through the opening years of this century.

Frankenthaler’s

distinguished, prolific career has been the subject of numerous monographic

museum exhibitions. The Jewish Museum and Whitney Museum shows were succeeded

by a major retrospective initiated by the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth that

traveled to The Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Los Angeles County Museum of

Art, and the Detroit Institute of Arts, MI (1989); and those devoted to works

on paper and prints organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

(1993), among others.

Select recent important exhibitions have included Painted on 21st Street:

Helen Frankenthaler from 1950 to 1959 (Gagosian, NY, 2013); Making

Painting: Helen Frankenthaler and JMW Turner (Turner Contemporary,

Margate, UK, 2014); Giving Up One’s Mark: Helen Frankenthaler in the 1960s

and 1970s (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, 2014–15); Pretty

Raw: After and Around Helen Frankenthaler (Rose Art Museum, Brandeis

University, Waltham, MA, 2015); As in Nature: Helen Frankenthaler,

Paintings and No Rules: Helen Frankenthaler Woodcuts (The Clark

Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, 2017); Abstract Climates: Helen

Frankenthaler in Provincetown (Provincetown Art Association and Museum,

MA, 2018, traveled to Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, NY, 2019);

and Pittura/Panorama: Paintings by Helen Frankenthaler, 1952–1992 (Museo

di Palazzo Grimani, Venice, 2019), the first presentation of the artist’s work

in Venice since its 1966 appearance at the 33rd Venice Biennale.

https://www.frankenthalerfoundation.org/helen/biography

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%201964.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio%20XX.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

%C2%A9%C2%A9photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio.jpg)

.png)