MAPPLETHORPE – RODIN AT MUSEE RODIN PARIS

April 8, 2014 – September 21, 2014

MAPPLETHORPE – RODIN

AT MUSEE RODIN PARIS

April 8, 2014 –

September 21, 2014

“I see things

like they were sculptures. It depends on how that form exists within the

space”. Robert Mapplethorpe

In a single

exhibition, the Musée Rodin brings together two forms of expression – Sculpture

and Photography – through the works of two major artists: Robert Mapplethorpe

and Auguste Rodin. Thanks to exceptional loans from the Robert Mapplethorpe

Foundation, this exhibition presents 50 sculptures by Rodin and a collection of

120 photographs, in a bold dialogue revealing the enduring nature of these

great artists’ favourite themes and subjects.

There would appear

to be little similarity between these two renowned figures, even though

Mapplethorpe continually sought to sculpt the body through photography and

Rodin used photography throughout his career.

Robert Mapplethorpe

sought the perfect form, while Rodin attempted to capture a sense of movement

in inanimate materials. There is no spontaneity in Mapplethorpe’s work,

everything is constructed, whereas Rodin retains the traces of his touch and

takes advantage of the accidental. One was attracted to men, the other to

women, obsessively in both cases. But this did not stop Mapplethorpe from

photographing female nudes, or Rodin from sculpting many male bodies.

Here, however, the

differences between these two artists are instantly transformed into an

unexpected dialogue. The curators have chosen seven themes, common to the work

of both, revealing connections in form, theme and aesthetic. Movement and

Tension, Black and White/Light and Shadow, Eroticism and Damnation are just

some of the major issues running through the works of the two artists.

This exhibition

invites visitors to challenge the dialogue established by the curators, and to

make their own comparisons. This “sculpture and photography” approach is

unprecedented, the first time such a confrontation has been presented, and

looks at both photography and sculpture from a new angle.

In parallel with

this, the Réunion des musées nationaux is organising a Mapplethorpe retrospective at the Grand Palais,

from 22 March to 14 July 2014.

Exhibition curators

Hélène Pinet, Head

of Photography Collections at the Musée Rodin

Judith

Benhamou-Huet, Art critic and journalist

Hélène Marraud,

Assistant curator, responsible for sculptures at the Musée Rodin

http://www.musee-rodin.fr/en/exhibition/exposition/mapplethorpe-rodin

AUGUSTE RODIN (1840-1917)

NIJINSKI 1912 ( DETAIL )

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

NU FEMININ A TETE DE

FEMME SLAVE, EMERGEANT D’UN VASE – VERS 1900?

Terre Cuite et Plâtre,

28,6 x 18,6 x 12,9 cm, Paris,

Musée Rodin, S. 3866

© Paris, Musée Rodin, photo C. Baraja

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917) - ASSEMBLAGE:

NU FEMININ DEBOUT

DANS UN VASE, VERS - 1900 ?,

Terre Cuite et

Plâtre, 47,5 cm x 20,7 x 14 cm,

Paris, Musée Rodin,

S. 379 © Paris, Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

KEN MOODY 1984

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

TORSE FEMININ, DIT

DU VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM - VERS, 1910-1914,

Plâtre, 63,5 x 38 x

23 cm, Paris, Musée Rodin,

S. 2895 © Paris,

Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

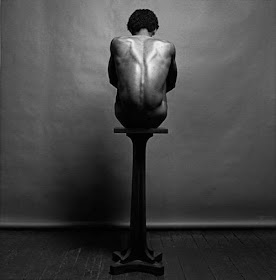

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989)

ROBERT SHERMAN 1983,

MAP 1236

© 2014 Robert

Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.

All rights reserved

&

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

TETE DELA LUXURE 1907

Plâtre, 37,8 x 30,2

x 28,3 cm, Paris

Musée Rodin, S. 1825

© Paris, Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

THE

CATHEDRAL 1908

Stone - H. 64 cm ;

W. 29.5 cm ; D. 31.8 cm

SCULPTURE AND ARCHITECTURE

In the second

half of the 19th century, Europe’s largest cities underwent an unprecedented

phase of transformation and modernization, similar to Baron Haussmann’s

redevelopment of Paris, which involved the construction of numerous public and

private buildings: operas, stock exchanges, chambers of commerce, fountains,

townhouses, etc.

To better

symbolize wealth and prosperity, these buildings were adorned with lavish

decorative sculpture, contracted out to studios run by ornamental sculptors

specialized in this type of work. Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824-87) was

one such case. Employing dozens of assistants, he was commissioned to decorate

several important Parisian buildings: the commercial court (1864), the Paris

Opera (1864-66) and the wings of the Louvre (1850-65).

When Rodin joined

Carrier-Belleuse’s studio in 1863, his fellow employees included some of his

former classmates from the École Spéciale de Dessin et de Mathématiques, known

as the “Petite École”, with whom he worked on the exterior decoration of the

mansion built on the Champs-Élysées for the Marchioness of Païva in 1865. For

the young sculptor, this employment above all offered him a certain job

security. Even though Rodin had obtained commissions in 1863 for the two

figures representing Drama and Comedy on the facade of the Théâtre des Gobelins

and for ornamental sculpture on the Théâtre de la Gaîté, his financial

situation remained precarious. He lacked both the prestige of those who

graduated from the École des Beaux-Arts and the advantages of its old-boy

network.

Rodin learned

a great deal from Carrier-Belleuse, whom he followed to Brussels when the

studio received major commissions there. It was a decisive phase in his

training in the field: he discovered the reality of running a large sculpture

studio, a business with a top-down hierarchical structure from master sculptor

to assistants and various craftsmen. Rodin would remember how it operated when

he set up his own studio in the early 1880s, after being awarded the

commissions for the Monument to the Burghers of Calais and The

Gates of Hell.

Rodin also

learned to cope with the demands of monumental stone sculpture. Having left

Carrier-Belleuse’s studio and formed a partnership with the Belgian sculptor

Antoine-Joseph Van Rasbourgh in 1873, Rodin worked on the interior decoration

of the Brussels stock exchange, notably on a Group of Children for

a pediment supported by two pairs of caryatids representing Trade and Industry,

inspired by those on the Garnier’s Opera, in Paris, and Rude’s figures on a

Brussels mansion. In 1871, Rodin and Van Rasbourgh commenced two exterior

groups adorning the summit of the south facade of the Brussels stock exchange,

originally entrusted to Carrier-Belleuse, Africa and Asia .

Although Rodin did not sign these works, he executed most of these allegorical

groups.

Commissions

on other building sites in Brussels soon followed: the Palais Royal (1872), the

Palais des Académies (1874) and a residential building on Boulevard Anspach

(1874), for whose façade Rodin sculpted three figures. Rodin’s return to Paris

in 1877 marked the end of this stage in his career, even if he occasionally

accepted offers of work “simply to pay the rent” involving ornamental sculpture

for the interiors of wealthy people’s homes.

Rodin’s

interest in architecture did not stop at these new buildings; it was far

broader and more eclectic.

In 1875,

leaving Belgium for a short while, he travelled to Italy via Rheims, where the

cathedral and its sculptures made a profound impression on him (Porches and

Belfry of Rheims Cathedral, 1905, D.7717). In autumn 1877, he began

his “cathedral tour” which took him all over France. He did not limit himself

to masterpieces of Gothic architecture, but, until the early years of the 20th

century, made regular visits to Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance and classical

French churches and castles (Interior of the Church of Sainte-Croix de

Quimperlé, c.1901, D.3580; Buttress of the Château d’Ussé,

1889-90, D.5818; Profiles of Cornices, D.3397; The Château

de l’Islette, c.1890 (?), D.3503).

In the late 19th century,

Rodin strongly opposed Viollet-le-Duc’s excessive restoration programmes and

ardently defended French architecture in an article entitled “Un sacrilège

national. Nous laissons mourir nos cathédrales” (“A national sacrilege. We are

letting our cathedrals die”), published in Le Matin (23 December 1909): “Snow, rain and sun

find me standing in front of them like a vagabond on the roads of France, and I

discover them over and over again, as if always seeing them for the first time.

To understand them, one needs only to be sensitive to the pathetic language of

those lines swollen with shadow and reinforced by the inclined form of plain or

decorated buttresses. To understand these lovingly modelled lines, one must be

lucky enough to be in love; for the mind may design, but it’s the heart that

models.”

Rodin’s

response to the expressive force of these buildings often lavishly adorned with

stone carvings led to the publication of his book Les Cathédrales de France in March 1914. Prefaced

by Charles Morice, it was a compilation of the notes, sketches and drawings

that Rodin had made since he began visiting churches and cathedrals in the late

1870s.

FROM THE DOORS OF A

DECORATIVE ARTS MUSEUM TO THE GATES OF HELL

From 1880

onwards, and from the moment he began his preliminary research for The Gates of Hell, these architectural tours had a

more pragmatic side to them. In 1880, Rodin in fact received a commission for a

monumental bronze door intended for the future Musée des Arts Décoratifs, not

yet built but envisaged on the site of the Cour des Comptes (Audit Office),

which burnt down during the Commune.

Rodin

initially based what would later become The Gates of Hell on Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise for the Florence Baptistry,

whose relief sculptures, executed in 1425-52, were arranged in panels and

medallions. Rodin made sketch after sketch,

before changing his mind and drawing his inspiration from motifs on Gothic

doors and carvings on tympanums of Romanesque churches, combined with

Renaissance window mouldings.

Rodin, for

whom “the commission of ‘The Gates of Hell’ demanded a more profound knowledge

of monument details”, effectively multipled the number of notes, sketches and

drawings that he jotted down in small notebooks – almost 2,000 – on his visits

to cathedrals. The sources of these sketches are sometimes hard to identify,

for while the drawings are relatively precise, instead of general views, they

often concern details – pillars, arches, mouldings and buttresses that show

Rodin’s interest in how the light fell upon and modelled these volumes (Entrance to the Abbey Church of Saint-Pierre d’Auxerre,

1881-84, D.5916-5918; Dijon Law Courts,

1908-1909, D.5891). “I’m turning into an architect,” he wrote. “I must, because

that’s how I’ll finish the things I need for my Porte.

The

decorative arts museum was never built. A railway station was constructed in

its place in 1900. By an ironic twist of fate, in 1986 this station became the

Musée d’Orsay, whose collections are now home to the plaster of The Gates of Hell.

Rodin’s love

of architecture would manifest itself in his sculpture time and time again. In

his investigations and assemblages, he sometimes combined figures and fragments

of bodies with elements of decorative architecture: columns, capitals,

pilasters, foliated plinths (The Sphinx, c.1886; Earth and Sea, c.1900; Spring and Mountain, before 1900; The Walking Man, on a Column, c.1885?). Architectural

fragments thus contributed to the overall movement and expressive force of his

figures.

His awareness

of the importance of the architectural surroundings prompted him to reflect

upon the visibility of his sculptures in an urban environment. In 1913, when

the English government purchased a cast of The Burghers of Calais, Rodin tried out an idea which

he had been pondering over since 1885. He wanted to place the group on top of a

very high base, so that it would be silhouetted against the sky and appear on

the same scale as the architecture – the monument was initially erected in

London’s Parliament Square. He thus had a five-metre-high scaffolding built in

his garden at Meudon, a mere few steps from his front door, to judge the effect

of such an installation.

Another

commission enabled Rodin to further pursue this combination of sculpture and

architecture. In March 1898, Armand Dayot, art critic and inspector general for

the Ministry of Fine Arts, aired an idea with Jules Desbois for a monument to

labour to be shown at the 1900 Universal Exposition. Desbois suggested other

sculptors who might be interested in working on the project. Although he had

been working for the event for several years, Dalou refused the offer, but

several others were pleased to accept: Falguière, Baffier, Charpentier,

Injalbert, Mercié, Meunier, and Rodin, obviously delighted with this idea for a

collective effort, as on cathedrals.

Rodin

coordinated the project and, in late 1898, submitted a plaster model

celebrating creative energy: it represented a staircase tower reminiscent of

both the towers of Pisa and the Château de Blois. Inside, the spiral staircase

winding around the central column adorned with bas-reliefs also recalled the

Trajane Column, Rome, and the Vendôme Column, Paris. It was surmounted by the Benedictions group, while the figures of Night and Day stood on the base, which led down to the

crypt.

The model was

shown in 1900, but no funding for the execution of the monument was

forthcoming. Thus, like many of the cathedrals that Rodin admired so much, his Tower of Labour remained unfinished.

FOR LOVE OF ARCHITECTURE

Rodin may not

have become a builder himself, but he assuaged his passion for architecture to

some extent by collecting photographs of architecture and by opting to live and

work amidst “old stones”.

In the 1890s,

he conducted his love affair with Camille Claudel in a semi-ruined rococo

mansion called the Folie Payen (or Folie-Neubourg), on the Boulevard d’Italie.

The main reasons for purchasing the Villa des Brillants, a modest, recently

built, Louis XIII-style home in Meudon was because of its magnificent view over

the Seine valley and the train service providing easy access to his Parisian

studios at the Dépôt des Marbres (rue de l’Université). The pavilion built in

1900 for his exhibition in the Place de l’Alma, and dismantled when the show

closed, was re-erected the following year at the sculptor’s request in his

garden at Meudon. Though modern in some respects (the structure was in metal),

the rotonda at its entrance, its portico and wide arched windows all drew their

inspiration from the rocaille style.

Between 1907

and 1910, Rodin found the means of having the central section of the facade of

the Château d’Issy-les-Moulineaux rebuilt in his garden. The original castle,

constructed by Pierre Bulet in the late 17th century, had been destroyed by

fire in 1871.

But this link between sculpture and architecture was probably forged

definitively when Rilke showed Rodin the Hôtel Biron (built in 1728-30 by the

architect Jean Aubert, who later designed the Stables at the Château de

Chantilly). Rodin was charmed by the building and its grounds, adjacent to the

prestigious Invalides complex with its domed chapel. Though scheduled for

demolition, the Hôtel Biron was temporarily occupied by artists. The premises

Rodin rented became his private study and reception rooms, before being chosen

to house the museum founded after the sculptor donated his entire works and

collections to the French nation. Rodin’s relationship with architecture was

thus just as decisive in his early career as at the end of his life and for the

works he left to posterity.

In 1908, Rodin carved a sculpture out of a block of stone, initially

called The Ark of the Covenant. Two right hands, held together in an upward spiralling

movement enclosing an empty space, recall a rib vault. This resemblance to a

Gothic vault, and the subsequent publication of Rodin’s book on cathedrals in

1914, prompted him to change the title to The Cathedral, thus

conveying the aspirations of the sculptor, driven by the constructive energy

and spiritual force expressed in his works.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Corps et décors. Rodin et les arts décoratifs,

exhibition catalogue, Musée Rodin, Paris, 2010.

- Vers L’Âge d’airain. Rodin en

Belgique, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Musée Rodin, 1997. In

particular Hélène Marraud, “Monuments et sculptures architecturales”, p. 81.

- Rodin en 1900. L’exposition de

l’Alma, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, 2001. In

particular Véronique Matiussi, “La Rodinière”, p. 52.

- Rodin. Le Musée et ses

collections, Scala, Paris, 1996. In particular Claudie Judrin, “Les

dessins d’architecture”, p. 45, and Alain Beausire, “Des lieux où vécut et

travailla Rodin”, p. 121.

- Antoinette

Le Normand-Romain & Annette Haudiquet, Rodin, Les Bourgeois de Calais, éditions du Musée

Rodin, Paris, 2001.

- Antoinette

Le Normand-Romain, La Porte de l’Enfer,

éditions du Musée Rodin, Paris.

- Antoinette

Le Normand-Romain & Hélène Marraud, Rodin à Meudon. La Villa des Brillants, éditions du

Musée Rodin, Paris, 1996.

MUSEE RODIN PARIS

MUSEE RODIN PARIS

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989)

KEN MOODY AT ROBERT

SHERMAN 1984, MAP 1354

© 2014 Robert

Mapplethorpe Foundation,Inc.

All rights reserved

&

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

TETE DE LA DOULEUR -

VERS 1901 – 1902

Bronze, 21,7 x 22,5

x 27 cm, Paris,

Musée Rodin, S. 1127

© Paris, Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

AJITTO 1981

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989)

WHITE GAUZE - 1984

Map 1330 © 2014

Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.

All rights reserved

&

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

TORSE DE L’AGE

D’AIRAIN DRAPE - VERS 1895

Plâtre, 78 x 49,5 x 31 cm, S.

3179

© Paris, Musée

Rodin, ph. C.

Baraja

BALZAC, SECOND STUDY FOR NUDE F,

KNOWN AS NUDE AS AN ATHLETE - 1896

Bronze - H. 93.1 cm ; W. 43.5 cm ; D. 35 cm

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989)

ORCHID 1982, MAP 949

© 2014 Robert

Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.

All rights

reserved

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989)

LUCINDA CHILDS 1985,

MAP 1656

© 2014 Robert

Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.

All rights reserved

&

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917) ASSEMBLAGE:

DEUX MAINS GAUCHES

Plâtre, 14,5 x 10,2

x 6,3 cm, Paris,

Musée Rodin, S. 1272

© Paris, Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989),

ORCHID 1985 -

Map 1579

© 2014 Robert

Mapplethorpe Foundation,

Inc. All rights reserved

&

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

IRIS MESSAGERE DES

DIEUX – VERS 1891-1893 ?

Terre Cuite, 40,3 x 41 x 19,1 cm,

Paris,

Musée Rodin, S. 6629 © Paris, Musée

Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

AUGUSTE RODIN (1840-1917)

NU FEMININ SORTANT

D’UN POT, VERS 1900 - 1904 ?

Terre Cuite et

Plâtre, 12,9 x 13,3 x 10 cm,

Paris, Musée Rodin,

S. 3718 © Paris, Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989),

GEORGE BRADSHAW -

1980

Map 504 © 2014

Robert Mapplethorpe

Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved

&

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

FEMMES DAMNEES –

AVANT 1890

Plâtre, 20 x 29 x

12,1 cm, Paris, Musée Rodin,

S. 41 © Paris, Musée

Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

THOMAS 1987

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989)

BILL T. JONES 1985,

MAP 1616

© 2014 Robert

Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.

All rights reserved

&

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

GENIE FUNERAIRE VERS

1898

Bronze, 85,7 x

39 x 32 cm, Paris,

Musée Rodin, S. 795

© Paris, Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

VINCENT 1981

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989),

FEET - 1982, MAP 895

© 2014 Robert

Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.

All rights reserved

&

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917) – PIED GAUCHE

Terre Cuite et Bois,

19,9 x 11,3 x 23,4 cm, Paris,

Musée Rodin, S. 3840

© Paris, Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

BUSTE DE HELENE DE

NOSTITZ 1902

Plâtre, 23,5 x 22,1

x 12 cm, Paris

Musée Rodin, S. 689

© Paris, Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

(1946-1989),

MICHAEL REED 1987 -

MAP 1728

© 2014 Robert

Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.

All rights

reserved

&

AUGUSTE RODIN

(1840-1917)

L’HOMME QUI MARCHE –

VERS 1899

Bronze, 85 x 59,8 x

26,5 cm, Paris,

Musée Rodin, S. 495

© Paris, Musée Rodin, ph. C. Baraja

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE

Robert Mapplethorpe was born in 1946 in Floral Park, Queens. Of his childhood he said, "I come from suburban America. It was a very safe environment and it was a good place to come from in that it was a good place to leave."

In 1963, Mapplethorpe enrolled at Pratt Institute in nearby Brooklyn, where he studied drawing, painting, and sculpture. Influenced by artists such as Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp, he also experimented with various materials in mixed-media collages, including images cut from books and magazines. He acquired a Polaroid camera in 1970 and began producing his own photographs to incorporate into the collages, saying he felt "it was more honest." That same year he and Patti Smith, whom he had met three years earlier, moved into the Chelsea Hotel.

Mapplethorpe quickly found satisfaction taking Polaroid photographs in their own right and indeed few Polaroids actually appear in his mixed-media works. In 1973, the Light Gallery in New York City mounted his first solo gallery exhibition, "Polaroids." Two years later he acquired a Hasselblad medium-format camera and began shooting his circle of friends and acquaintances—artists, musicians, socialites, pornographic film stars, and members of the S & M underground. He also worked on commercial projects, creating album cover art for Patti Smith and Television and a series of portraits and party pictures for Interview Magazine.

In the late 70s, Mapplethorpe grew increasingly interested in documenting the New York S & M scene. The resulting photographs are shocking for their content and remarkable for their technical and formal mastery. Mapplethorpe told ARTnews in late 1988, "I don't like that particular word 'shocking.' I'm looking for the unexpected. I'm looking for things I've never seen before … I was in a position to take those pictures. I felt an obligation to do them." Meanwhile his career continued to flourish. In 1977, he participated in Documenta 6 in Kassel, West Germany and in 1978, the Robert Miller Gallery in New York City became his exclusive dealer.

Mapplethorpe met Lisa Lyon, the first World Women's Bodybuilding Champion, in 1980. Over the next several years they collaborated on a series of portraits and figure studies, a film, and the book,Lady, Lisa Lyon. Throughout the 80s, Mapplethorpe produced a bevy of images that simultaneously challenge and adhere to classical aesthetic standards: stylized compositions of male and female nudes, delicate flower still lifes, and studio portraits of artists and celebrities, to name a few of his preferred genres. He introduced and refined different techniques and formats, including color 20" x 24" Polaroids, photogravures, platinum prints on paper and linen, Cibachrome and dye transfer color prints. In 1986, he designed sets for Lucinda Childs' dance performance, Portraits in Reflection, created a photogravure series for Arthur Rimbaud's A Season in Hell, and was commissioned by curator Richard Marshall to take portraits of New York artists for the series and book, 50 New York Artists.

That same year, in 1986, he was diagnosed with AIDS. Despite his illness, he accelerated his creative efforts, broadened the scope of his photographic inquiry, and accepted increasingly challenging commissions. The Whitney Museum of American Art mounted his first major American museum retrospective in 1988, one year before his death in 1989. His vast, provocative, and powerful body of work has established him as one of the most important artists of the twentieth century. Today Mapplethorpe is represented by galleries in North and South America and Europe and his work can be found in the collections of major museums around the world. Beyond the art historical and social significance of his work, his legacy lives on through the work of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. He established the Foundation in 1988 to promote photography, support museums that exhibit photographic art, and to fund medical research in the fight against AIDS and HIV-related infection.

http://www.mapplethorpe.org/biography/

THE

HUMAN BODY IN RODIN'S SCULPTURE:

NATURE AND IDEAL, MOVEMENT AND

EXPRESSION

In May 1903, at the

Burlington Fine Arts Club, London, Rodin saw a marble ‘ Head of a Young Woman

‘, from Chios, belonging to Edward Perry Warren, a collector who had

commissioned a marble version of ‘ The Kiss ‘ three years earlier. The sculptor

initially sought to exchange several of his own works for this Greek sculpture,

then tried to purchase it at any price, but all his efforts were in vain. Rodin

eventually “compensated” for his frustration the following year by writing and

publishing an article on the work in the periodical ‘ Le Musée, Revue d’Art Antique’.

From the moment he first laid eyes on this ‘ Warren Head ‘, Rodin could not

contain his admiration, which he proclaimed in an interview given to a

journalist from the ‘ Morning Post ‘ : “It’s life itself. It embodies all that

is beautiful, life itself, beauty itself. It is admirable. Those parted lips. I

am not a man of letters; hence I am unable to describe this truly great work of

art. I feel but I cannot find the words that will give expression to what I

feel. This is a Venus! You cannot imagine how much this Venus interests me. She

is like a flower, a perfect jewel. So perfect that it is as disconcerting as

nature itself. Nothing could describe it.” (“Interview with M. Rodin: A

Praxiteles Venus”, Morning Post, 28 May 1903) This anecdote and the exuberant

praise expressed by the sculptor, who was then at the height of his artistry,

reveal the primordial role awarded to the human body in his oeuvre, far beyond

simple questions of anatomical accuracy. Throughout his career, the body as a

vehicle for expression of the impulses of the soul, of passion, effectively

constituted an inexhaustible source of inspiration in his search for the

perfect means of combining ideal antique beauty with the mystery of nature.

RODIN, THE ANTIQUE IDEAL AND MICHELANGELO

“Come and see me tomorrow morning at

Meudon. We will talk of Phidias and Michelangelo, and I will model statuettes

for you on the principles of both. In that way you will quickly grasp the

essential differences of the two inspirations, or, to express it better, the

opposed characteristics which divide them.” This invitation made by Rodin to

Paul Gsell c.1910, and the modelling session and explanations that followed (in

Rodin on Art and Artists: Conversations with Paul Gsell, “Phidias and

Michelangelo”) reveal how aware the sculptor was of the contradictory

influences exerted on his own art by Phidias’ classical example and

Michelangelo’s more tormented.

In his early years of training, Rodin began studying

Greek antiques and master sculptors in the Louvre, where he spent hours

drawing. The numerous sketches and studies that he made in the early 1870s bear

witness to his ongoing interest in the diverse models offered by different

periods in art history. On the same sheet of paper, Rodin glued drawings of column

statues of queens in Chartres Cathedral next to figures from the Parthenon

frieze, showing how receptive he was to the expressive force peculiar to each

of these aesthetic canons. This would later be borne out by the scope and

heterogeneity of his collection of sculptures, in which the arts of Ancient

Egypt, Greece and Rome, the Middle East, the Far East and the Middle Ages were

all represented. This expression of the antique ideal emerged in 1863, in Man

with the Broken Nose (1863-75), among the first of Rodin’s works to move away

from the more decorative style prevalent in Carrier-Belleuse’s studio. Using an

old workman from the Saint-Marcel district of Paris as the sitter for his

portrait bust, Rodin abandoned the search for individual resemblance so as to

be closer to antique sculptures. He thus emphasized the facial features of his

sitter (broken nose, wrinkles, beard) and transformed him into a Greek

philosopher. Between 1876 and 1915, Rodin made several visits to Italy,

initially to discover the works of his masters, Donatello and Michelangelo,

then to nurture and revive his relationship with them. He admired the emotional

quality of Michelangelo’s figures, their twisting poses, the expressive force

of non finito. On his very first journey, he filled sketchbook after sketchbook

with studies. In the early 1870s, the Florentine artist’s influence on Rodin

was particularly evident in his manner of sculpting the bodies of monumental

figures when working for CarrierBelleuse in Brussels: witness the Caryatids and

Atlantes on the facade of a residential building in Boulevard Anspach, and the

groups he carved for the Chamber of Commerce. The four figures with powerful

musculature and twisting poses, modelled in the Pedestal of the Titans in the

1870s, epitomized the fruits of his research. Further evidence of Rodin’s debt

to Michelangelo can be seen in the resemblance between the model’s pose in ‘

The Age of Bronze ‘ (1877) and that of the Dying Slave (1513), as well as in

the similarity of the modelling of the man’s back to Michelangelo’s handling of

a Male Nude in a pen and ink drawing (1505), now in the Casa Buonarroti,

Florence. This influence was again apparent in 1881, when Rodin, engrossed in

the design and execution of The Gates of Hell, seems to have borrowed the pose

for his Eve from her eponymn in Michelangelo’s scene of The Expulsion from

Paradise, painted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1508-12). He also drew

his inspiration for her pendant, Adam (1880-81), directly from the section of

the fresco entitled The Creation of Adam

CAPTURING

BODY AND SOUL IN MOTION

From The Age of Bronze onwards, Rodin preferred to

depict a body in motion rather than to work from a fixed, academic pose.

Auguste Neyt, a young Belgian soldier whom he used as a model, remembered

coming into his studio, where “I had to train myself to strike the pose. It was

hardly an easy thing to do. Rodin did not want straining muscles; in fact, he

loathed the academic ‘pose’… The master wanted ‘natural’ action taken from real

life.” (cited by Butler) Towards the end of his life, the sculptor, in turn, described

his working method to Paul Gsell: “As for me, seeker after truth and student of

life as I am… I take from life the movements I observe, but it is not I who

impose them. Even when a subject which I’m working on compels me to ask a model

for a certain fixed pose, I indicate it to him, but I carefully avoid touching

him to place him in the position, for I will reproduce only what reality

spontaneously offers me. I obey Nature in everything, and I never pretend to

command her. My only ambition is to be servilely faithful to her.” (Gsell, p.

11). This search for the veracity of nature and movement led him away from the

accepted norms of bodily representation. Breaking with tradition, he chose to

portray a fragmentary figure in The Walking Man (1907) – a male torso, with

neither head nor arms, planted on two legs opened like a compass. Having

eliminated all anecdotal details to focus on the sensation of movement, Rodin

produced an unprecedented and powerfully expressive interpretation of it,

reiterating the force that had so captivated him when standing before

incomplete antique statues and Michelangelo’s unfinished works. In the early

1910s, while conversing with Rodin, Paul Gsell argued that what proved that he

changed nature was “that the cast would not give at all the same impression as

your work”. Rodin reflected an instant and said: “That is so! Because the cast

is less true than my sculpture! It would be impossible for any model to keep an

animated pose during all the time that it would take to make a cast from it.

But I keep in my mind the ensemble of the pose and I insist that the model

shall conform to my memory of it… The cast only reproduces the exterior; I

reproduce, besides that, the spirit which is certainly also part of nature. I

see all the truth, and not only that of the outside.” (Gsell, p. 11) This

desire to capture the impulses of the soul through bodily movement may explain

Rodin’s love of dance, which was one of his major sources of inspiration. He

would rather sketch dancers than models in traditional sittings. Unlike an

artist such as Degas, Rodin was not interested in classical ballet but

preferred experimental dance as performed by Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan,

Nijinsky and the Ballets Russes, who liberated dance from artifice and convention

and attained new heights of freedom. Rodin’s enthusiasm had ample opportunity

to manifest itself: in 1889, at one of the events programmed for the Universal

Exposition, he made drawings at a performance given by a Javanese dance

company. In 1906, the King of Siam visited Paris, accompanied by a troupe of

Cambodian dancers, whom Rodin followed to Marseilles.

He executed about fifty life drawings of them in

watercolours, notably studies of hand movements. The following year, Loie

Fuller arranged for Rodin to attend a show performed by the Japanese dancer

Hanako, whom he then regularly asked to pose, over the next few years until

1911, for numerous drawings and a series of masks. During the same period, he

paid Alda Moreno, an acrobatic dancer at the Opéra-Comique, to pose for him and

modelled a series of small sculptures of her. The sculptor’s extremely free

anatomical handling attempted to capture all the energy of her dance movements.

In 1912, Nijinsky also posed for Rodin, who defended him when L’Après-midi d’un

faune caused an outrage in the press: “The reason why we loved Loie Fuller,

Isadora Duncan and Nijinsky so much was because they recovered the freedom of

instinct and rediscovered the sense of a tradition based on a respect for

nature.”

EROS

Both

dance and the female body were thus always important sources of inspiration for

Rodin, who, throughout his career, produced several interpretations full of

sensuality, or eroticism: Faun and Nymph (c.1886, inv. S. 363), The Female

Martyr, Crouching Woman (1906-08, inv. S. 1156), Iris, Messenger of the Gods

(1895, inv. S.1068), The Eternal Idol, Danaïd, Sin... Working while

observing a life model played a fundamental role in Rodin’s creative process.

In his address books, he used to jot down the names of his models (men, women,

young and old people…), together with notes about their physical

characteristics. Instead of requesting decorous academic poses, the sculptor

always preferred to give them tremendous leeway in the poses they adopted, as

he sought to capture true movement in the countless drawings he made “from

life”, without taking his eyes off the model. In these “drawings without

looking”, the artist accepted, and sought, the anatomical distortions and

sculptural innovations produced by this type of working method: “Since I

began,” Rodin declared enthusiastically, “I have the impression that I know how

to draw… And I know why my drawings have this intensity: it’s because I do not

intervene. Between nature and paper, I eliminated talent. I do not reason. I

simply let myself go.”.(cited in Figures d’Eros, p. 50) From the mid-1890s

onwards, in fact, his drawings and watercolours of female nudes revealed new

phases of his investigations. Henceforth far less influenced by Michelangelo,

these works also attested to greater synthesis and extraordinary artistic and

moral freedom: the uninhibited bodily movements were frequently captured from

unprecedented viewpoints. In 1897, the art critic Roger Marx offered the first

analysis of this new type of drawing, which he called “snapshots of the female

nude” (Roger Marx, “Cartons d’artistes. Auguste Rodin”, L’image, 1897 (pp.

292-9).

Rodin’s fascination for Sapphic couples, which he

shared with Toulouse-Lautrec, Charles Baudelaire, Pierre Louÿs, Paul Verlaine

and his predecessor Gustave Courbet, was evident in several of his drawings. In

all these drawings, Rodin assuaged his curiosity in privileged posing sessions

with the models. There was no visual compromise nor stage effects: the nude was

not “arranged in a pose” as in Edgar Degas and Edouard Manet’s “studied”

painting. Their compelling eroticism added a touch of scandal to these works,

and established a parallel with Japanese prints, much sought after by art

lovers at this time and much admired by Rodin, as the Goncourt brothers

remarked and commented somewhat ironically upon in their Journal (5 January

1887): “Rodin, who is in a faunish frame of mind, asked to see my erotic

Japanese prints, and swooned with admiration before the women’s drooping heads,

the broken lines of their necks, the rigid extensions of arms, the contractions

of feet, all the voluptuous and frenetic reality of coitus, all the sculptural

entwining of bodies, melded and interlocked in the spasm of pleasure.”

(Goncourt, Vol. III, p. 3) Rodin’s feelings towards the “old stones” in his

collection of antiques could likewise be described as amorous. One evening, in

the glow of the lamplight, he went into raptures over an antique statue of

Aphrodite that he was showing to Paul Gsell: “Is it not marvellous?”… “Just

look at these numberless undulations of the hollow which unites the body to the

thigh… Notice all the voluptuous curvings of the hip… And now, here, the

adorable dimples along the loins.” He spoke in a low voice, with the ardor of a

devotee, bending above the marble as if he loved it. “It is truly flesh!,” he

said… “You would think it moulded by kisses and caresses.” Then, suddenly,

laying his hand on the statue, “You almost expect, when you touch this body, to

find it warm.” (Gsell, p. 21) BIBLIOGRAPHY

http://www.musee-rodin.fr/en/resources/educational-files/human-body-rodinssculpture

You may visit to see source of essay, photographs and

whole bibliography of Auguste Rodin to click above link.

RODIN AND PHOTOGRAPHY

Almost twenty years

after Nicéphore Niepce’s early experiments, photography officially entered the

annals of history on 7 January 1839, when François Arago, physicist, astronomer

and Republican member of the French Assembly, presented the “daguerreotype”, a

process invented by Louis-Jacques Daguerre, to the Parisian Academy of Science.

From then on, there was an open debate, especially within the walls of France’s

Academy of Fine Arts, between the supporters and detractors of this new means

of producing images. The basic argument revolved around the following

questions: was photography a “mechanical” tool for capturing reality, or did it

leave room for an interpretative and expressive approach? In other words, was a

photograph a document or a work of art? While Pictorialist photographers such

as Stieglitz, Käsebier, Langdon Coburn and Steichen endeavoured to have

photography recognized as an artistic medium in the 1890s, this status was not

really acquired until after World War II.

Moreover, a rapport

between photography and sculpture very soon emerged. From the 1840s onwards,

pioneering photographers, including Niépce, Daguerre, William Henry Fox Talbot

and Hippolyte Bayard, found that the ornamental plaster or marble statuettes

favoured in middle-class homes made ideal photographic subjects. To quote Fox

Talbot: “Statues, busts, and other specimens of sculpture, are generally well

represented by the Photographic Art; and also very rapidly in consequence of

their whiteness. These delineations are susceptible of an almost unlimited

variety: since in the first place, a statue may be placed in any position with

regard to the sun, either directly opposite to it, or at any angle: the

directness or obliquity of the illumination causing of course an immense

difference in the effect.” (The Pencil of Nature,

London, Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1844)

EVIDENCE FOR THE

DEFENCE: THE PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE AGE OF BRONZE

Photography’s affinity with sculpture, as well as its documentary

and evidential value, may explain Rodin’s early interest in this new medium. In

1877, his submission to the Paris Salon, The Age of Bronze,

was the subject of huge controversy. Its critics accused Rodin of not having

modelled this male figure, but of having used a life cast. The sculptor reacted

by employing photographer Gaudenzio Marconi, who supplied art students with

images, to take a series of shots of both the plaster version of The Age of Bronze and Auguste Neyt, the model who had posed

for the work, so that they could be used as proof in his defence. This decision

shows how irrefutable Rodin considered photographic evidence to be. In fact, as

Michel Frizot explains, he chose to prove his innocence, not by producing a

live cast of the actual model in the same pose, but by comparing photographs of

the plaster version of the work and the sitter.

On several occasions Rodin made remarks expressing his reservations about photography, limiting it to its capacity for accuracy and elementary realism, not considering it to be a means of expression or artistic discipline in its own right. His famous outburst against photography “which lies”, as related by Paul Gsell, is a brilliant illustration of his standpoint:

“If, in fact, in instantaneous photographs, the figures, though taken while moving, seem suddenly fixed in mid-air, it is because, all parts of the body being reproduced exactly at the same twentieth or fortieth of a second, there is no progressive development of movement as there is in art. […] it is the artist who is truthful and it is photography which lies, for in reality time does not stop, and if the artist succeeds in producing the impression of a movement which takes several moments for accomplishment, his work is certainly much less conventional than the scientific image, where time is abruptly suspended.”

On several occasions Rodin made remarks expressing his reservations about photography, limiting it to its capacity for accuracy and elementary realism, not considering it to be a means of expression or artistic discipline in its own right. His famous outburst against photography “which lies”, as related by Paul Gsell, is a brilliant illustration of his standpoint:

“If, in fact, in instantaneous photographs, the figures, though taken while moving, seem suddenly fixed in mid-air, it is because, all parts of the body being reproduced exactly at the same twentieth or fortieth of a second, there is no progressive development of movement as there is in art. […] it is the artist who is truthful and it is photography which lies, for in reality time does not stop, and if the artist succeeds in producing the impression of a movement which takes several moments for accomplishment, his work is certainly much less conventional than the scientific image, where time is abruptly suspended.”

Rodin’s concept of

photography was in line with the prevailing views held in his day:

photography’s merit lay in its documentary precision, its ability to reproduce

mechanically, faithfully and with neutrality,and not in any artistic capacity.

Yet the photographic image, strictly factual and documentary in Rodin’s eyes at

the time of The Age of Bronze, would soon become part of and then influence his

creative process, although he apparently never used a camera himself. As the

medium that put his works into public circulation, photography also helped

maintain his reputation as an artist.

RODIN, COLLECTOR OF

PHOTOGRAPHS

Rodin was a keen

collector and an imaginative user of photography. By the end of his life, his

collection and archives numbered no less than 7,000 prints. The nature and

quality of these photographs differ, combining documentary and artistic images.

Their themes and subjects are worth commenting upon further.

1) Rodin’s

collection of photographs includes pictures of architecture, landscapes and

academic nudes assembled by the sculptor himself. Although these photographs

are very good quality, they are not the outstanding feature of his collection:

rather, part of a stock of photographs used by artists of his period in the elaboration

of their compositions.

2) Photographing

artworks became popular in the 1850s. As was common practice among sculptors

during this period, Rodin had his works photographed as soon as they were shown

at the Salons, from the early 1870s onwards. These pictures were intended for

his own personal archives, for his patrons or the purchasers of his sculptures,

as well as for publication in art reviews to ensure his works reached a broader

public. Rodin employed specialist photographers, such as Gaudanzio Marconi,

Karl Bodmer, Victor Pannelier and E. Freuler....

An objective

viewpoint, direct lighting and precise contours were the main characteristics

of these photographs that kept track of his studio production, essentially

during the period of Rodin’s commissions for monuments in the 1880s, when his

activity had increased to such a point that he was using four studios, in and

around the Dépôt des Marbres. These photographs, sometimes kept together in a

file, enabled Rodin to follow the different stages in the gestation of a

sculpture, as did the clay models from which he had plaster casts made.

Although Rodin used photography mainly for documentary purposes at this time, he soon began looking for photographers who were other than simple technicians and could propose a more artistic vision of his work. In 1896, he thus employed Eugène Druet, an amateur photographer and the owner of café that Rodin had patronized since 1893. In 1900, after the two men had temporarily fallen out while preparing for the exhibition in the Pavillon de l’Alma, Jean Limet, another amateur photographer and the patinator of Rodin’s bronzes, was commissioned to take the photographs to be published in the catalogue. The remarkable fruits of his investigations into colour can be seen in his bichromated-gelatin prints.

Although Rodin used photography mainly for documentary purposes at this time, he soon began looking for photographers who were other than simple technicians and could propose a more artistic vision of his work. In 1896, he thus employed Eugène Druet, an amateur photographer and the owner of café that Rodin had patronized since 1893. In 1900, after the two men had temporarily fallen out while preparing for the exhibition in the Pavillon de l’Alma, Jean Limet, another amateur photographer and the patinator of Rodin’s bronzes, was commissioned to take the photographs to be published in the catalogue. The remarkable fruits of his investigations into colour can be seen in his bichromated-gelatin prints.

Encouraged by Rodin,

Druet became a picture dealer in 1903. The sculptor then signed a contract with

the publisher Jacques-Ernest Bulloz, who brought out a portfolio of photographs

of Rodin’s sculptures that same year.

In 1896, at an exhibition held at the Musée Rath, in Geneva, Rodin showed photographs for the first time alongside his sculptures and drawings. He was so pleased with the experience that he repeated it, notably at the Pavillon de l’Alma exhibition, where 71 photographs were displayed next to his sculptures and drawings.

In 1896, at an exhibition held at the Musée Rath, in Geneva, Rodin showed photographs for the first time alongside his sculptures and drawings. He was so pleased with the experience that he repeated it, notably at the Pavillon de l’Alma exhibition, where 71 photographs were displayed next to his sculptures and drawings.

3) Rodin frequently

retouched the photos of his sculptures in pencil, pen or with a brush, but for

several different reasons:

Some of the pencil or ink amendments indicated the corrections to be given to the photographer (e.g. to emphasize a shadow), or to the engraver when the photograph was to be published. For Rodin, retouching a photo was often a vigorous exercise, as his pen strokes inked out whole areas of the image.

The sculptor also used retouched photographs as a starting point for his illustrations of Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil.

Many of these photos with amendments correspond to Rodin’s different ideas about the work in progress: photography was a tool that helped him to project a mental image of the sculpture. Rodin gave his photographers strict instructions as to how he wanted these photographs to be taken. They served as an aid in the gestation of a sculpture. The amendments Rodin made to them represented the changes that he envisaged making. This rapid retouching of the photos in pen, pencil or ink wash enabled him to fix in his mind exactly what he wanted to do before reworking the plasters. According to Michel Frizot, Rodin regarded the photographic medium as “a transaction surface” that allowed him to rework a creative idea visually rather than manually.

Some of these modifications, however, were never transposed onto the sculptures, and the photographs thus retouched, notably with gouache to isolate the figure, in which the image became an end in itself, acquired the status of artworks in their own right.

Some of the pencil or ink amendments indicated the corrections to be given to the photographer (e.g. to emphasize a shadow), or to the engraver when the photograph was to be published. For Rodin, retouching a photo was often a vigorous exercise, as his pen strokes inked out whole areas of the image.

The sculptor also used retouched photographs as a starting point for his illustrations of Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil.

Many of these photos with amendments correspond to Rodin’s different ideas about the work in progress: photography was a tool that helped him to project a mental image of the sculpture. Rodin gave his photographers strict instructions as to how he wanted these photographs to be taken. They served as an aid in the gestation of a sculpture. The amendments Rodin made to them represented the changes that he envisaged making. This rapid retouching of the photos in pen, pencil or ink wash enabled him to fix in his mind exactly what he wanted to do before reworking the plasters. According to Michel Frizot, Rodin regarded the photographic medium as “a transaction surface” that allowed him to rework a creative idea visually rather than manually.

Some of these modifications, however, were never transposed onto the sculptures, and the photographs thus retouched, notably with gouache to isolate the figure, in which the image became an end in itself, acquired the status of artworks in their own right.

4) Rodin proved to be

very sensitive to how other artists regarded his works. Among the photographers

with whom he preferred working were Edward Steichen, Alvin Langdon Coburn,

Gertrüd Käsebier, Stephen Haweis and Henry Coles.

On Rodin’s death in

1917, his archives and collection of photographs sank into oblivion, despite

the numerous acquisitions made by Léonce Bénédite, the Musée Rodin’s first

curator, who completed the existent, already substantial, body of work.

Rediscovered in the late 1960s, it was not truly brought to light again until

the 1970s.

In 1979, an article on Druet was included in the catalogue of a Rodin exhibition held in East Berlin. In 1981, the photographs of Rodin’s works featured prominently in the vast Rodin retrospective organized in Washington by Albert Elsen and Kirk Varnedoe.

Since the 1880s, the Musée Rodin has laid the emphasis on studying, conserving and highlighting the importance of the photographic collections and archives. Today these contain approximately 25,000 photgraphs.

In 1979, an article on Druet was included in the catalogue of a Rodin exhibition held in East Berlin. In 1981, the photographs of Rodin’s works featured prominently in the vast Rodin retrospective organized in Washington by Albert Elsen and Kirk Varnedoe.

Since the 1880s, the Musée Rodin has laid the emphasis on studying, conserving and highlighting the importance of the photographic collections and archives. Today these contain approximately 25,000 photgraphs.

Auguste Rodin, Paul

Gsell, Rodin on Art and Artists: Conversations with Paul Gsell,

Courier Dover Publications, 1983.

Rodin, under the direction of Claude Keisch, exhibition catalogue, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, 1979.

Rodin Rediscovered, under the direction of Albert E. Elsen, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1981.

Les photographes de Rodin, under the direction of Monique Laurent. Catalogue by Hélène Pinet, Photography Department, Musée Rodin, Paris, 1986.

Rodin en 1900. L’exposition de l’Alma, exhibition catalogue, Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, 2001.

Rodin et la photographie, under the direction of Hélène Pinet, Gallimard/Musée Rodin, Paris, 2007. Notably Michel Frizot, “La photographie, une surface de transaction” (pp. 14-17), and Hélène Pinet, “Dans l’atelier. L’œil du photographe. Le regard de Rodin” (pp. 24-29).

Sculpter-photographier. Photographie-sculpture, Proceedings of the conference held at the Louvre under the direction of Michel Frizot and Dominique Païni, éditions Marval/Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1993. Notably Hélène Pinet, “La sculpture, la photographie et le critique” (pp. 85-92).

Rodin, under the direction of Claude Keisch, exhibition catalogue, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, 1979.

Rodin Rediscovered, under the direction of Albert E. Elsen, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1981.

Les photographes de Rodin, under the direction of Monique Laurent. Catalogue by Hélène Pinet, Photography Department, Musée Rodin, Paris, 1986.

Rodin en 1900. L’exposition de l’Alma, exhibition catalogue, Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, 2001.

Rodin et la photographie, under the direction of Hélène Pinet, Gallimard/Musée Rodin, Paris, 2007. Notably Michel Frizot, “La photographie, une surface de transaction” (pp. 14-17), and Hélène Pinet, “Dans l’atelier. L’œil du photographe. Le regard de Rodin” (pp. 24-29).

Sculpter-photographier. Photographie-sculpture, Proceedings of the conference held at the Louvre under the direction of Michel Frizot and Dominique Païni, éditions Marval/Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1993. Notably Hélène Pinet, “La sculpture, la photographie et le critique” (pp. 85-92).

You may visit Musee

Rodin’s web page to have more information about Auguste Rodin to click above

link.

%2B%2BAuguste%2BRodin%2C%2BBuste%2Bde%2BHelene%2Bde%2BNostitz%2B(1902).jpg)

%2B-%2BAuguste%2BRodin%2C%2BTete%2Bde%2Bla%2Bluxure%2B(1907).jpg)

%2B-%2BAuguste%2BRodin%2C%2BTete%2Bde%2Bla%2Bdouleur%2B(vers%2B1901-1902).jpg)

%2B-%2BAuguste%2BRodin%2C%2BTorse%2Bde%2Bl'age%2Bd'airain%2Bdrape%2B(vers%2B1895).jpg)

%2B-%2BAuguste%2BRodin%2C%2BIris%2Bmessagere%2Bdes%2Bdieux%2B(vers%2B1891-1893).jpg)

%2B-%2BAuguste%2BRodin%2C%2BFemmes%2Bdamnees%2B(avant%2B1890).jpg)

%2B-%2BAuguste%2BRodin%2C%2BGenie%2Bfuneraire%2B(vers%2B1898).jpg)

%2B-%2BAuguste%2BRodin%2C%2BL'homme%2Bqui%2Bmarche%2B(vers%2B1899).jpg)