FRENCH PAINTER FABIENNE VERDIER

FRENCH PAINTER FABIENNE VERDIER

POLYPHONY OF GRAVITATION

Doris von Drathen

When a bolt of lightning pierces the heavens, there is no

time for words. Afterward we describe its brief flash as a trace, as something

that we saw. It is almost impossible to seize hold of the event that is the

present moment. It occurs, it ushers itself into existence, but that self has

neither existence nor duration. It is the border between being and existence;

it is a function.1 Thus the hic et nunc, the endeavor to nonetheless grasp the

precise instant of absolute present, remains one of the great, recurring

challenges for those artists who, comparable to alchemists, search for the very

essence of our existence, seek out that moment when sacred terror renders us

speechless. For this sliver of time has the power of opening up a fissure onto

an immensity lying beyond the bounds of our everyday life.

This breathtaking event of an absolute present, which rushes

with all its power into human awareness, is the incantatory energy that casts

its spell on the viewer standing before the paintings of Fabienne Verdier. The

viewer sees the traces of the brush occurring here and now, as if the acutely

immediate coming-to-existence of these pictorial events were occurring right

before his eyes.

The radical statements of the individual brushstroke run

like a crevice through the endlessly flowing texture of time and space. This

trace of the brush is the central focus in the œuvre of this transgressor of

frontiers who, in fact, has created a sculptural painting. The viewer

understands intuitively that he is not standing in front of a representational

image here, but instead is participating in a painterly event within the

dynamic field of the real space in which he himself is situated. Thus the

presence of the vehement brushstroke gives rise in the viewer to a heightened sense

of “being-in-space.” He becomes instantaneously aware of his own rootedness in

the present, his own gravitation and groundedness. It is as if the radical

instant of the present were to go hand in hand with the precision of that

inalienable, indivisible point that connects us to the very core of the earth.

The brushstrokes can take on the forms in which the universe

moves. They can cut through the space as axial planetary paths, can flow in

meandering currents or ramify into arboreal structures, can rear up wildly and

break away in vigorous sweeps; they can pull away in the vast zigzags of

beating wings or mountain ranges, can conglomerate into heavy, rocklike

masses—nevertheless these abstract forms, which do not strive for a geometry of

appearances but instead for an embodiment of space and its energies, always

arise from one broad painterly stroke, from a single movement of the large

Chinese brush that, after a period of pause and concentration, rushes with

emphatic finality through the space of the canvas.

Like the striking of a gong, which we not only perceive

acoustically but also feel with the resonance of our body, so do we experience

this pictorial event not only in visual terms, but also through the much more

highly differentiated sensorium of corporeal perception. Only a physical

being-in-space, receptive to the entire spectrum of sensory impressions, can

usher into experience the actual dimension of this painterly occurrence, namely

the event of a brushstroke that embodies an energy flow in the space that we

share with it. Whoever becomes open to this nonrational sensory perception will be able to feel the

forces of gravitation, of adhesion or cohesion, of magnetism; the power of the

breath and of flowing emptiness; the energies of sound and of color. For these

are the painterly materials of this abstraction, which cannot be classified

according to any customary aesthetic categories. The more deeply the viewer

comes to resonate with these pictorial spaces and their movement, the more his

perception casts off the overlying rhythms of everyday life, and the more the

dynamically charged energy field of these spaces transfers

itself onto his consciousness and gradually transforms it with new energies.

Perspective does not exist—like the horizon, or like the

axial intersection of horizontality and verticality, it numbers among the

visual habits to which we are so accustomed that, against our better judgment,

we perceive them as given realities. Space knows nothing of our inventions,

which serve to reduce its unfathomable immensity. One of these

perceptions—disregarding the actual knowledge of physics—is the idea that the

life-space through which we move is static. At the same time, we adhere to the

age-old conviction that its appearances are bound to the present instant, that

space is “actually” nothing other than a stream of permanently

self-renewing impulses, in other words “occurrences in

time.” Max Raphael designates the interplay of elements that come to appearance

in space and through space, and which establish their energy-dialogue in the

permanent weaving of a magnetic interdependence, as a “time of dynamic action.”2

This is the power of spatial impact, which we sense in

the brushstrokes of Fabienne Verdier. What we experience is our own unmistakable

connection to the forces at the core of the earth. What we sense is the

manifestation of energies that are alive in

space and that influence our life.

http://fabienneverdier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/essay_doris_von_drathen.pdf

MARGARETE, LA PENSEE LABYRINTHIQUE II - 2011

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 180 × 356 cm

Dimensions: 180 × 356 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

MARGARETA I ,

2011

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 180 × 403 cm

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 180 × 403 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

LA FAILLE 2014

Installation of a Monumental Painting in Majunga Tower, La Défense

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 12 × 8 m

Installation of a Monumental Painting in Majunga Tower, La Défense

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 12 × 8 m

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

LA FAILLE 2014 ( DETAIL )

PAYSAGE DE FLUX 2007

Polyptyque Horizontal en Résonance Avec Willem de Kooning

Dimensions: 183 × 610 cm

Collection Foundation H. Looser, Zurich

Polyptyque Horizontal en Résonance Avec Willem de Kooning

Dimensions: 183 × 610 cm

Collection Foundation H. Looser, Zurich

ARCHIPEL 1 - 2005

Serigraphy Printed in 8 Colours

Dimensions: 110 × 75 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

COLOR FLOWS 6 - 2012

Mixed Media on Canvas

Dimensions: 60 × 140 cm

Courtesy of Art Plural Gallery, Singapore

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

LIGNE ESPACE – TEMPS N° 04, 2009

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 352 × 320 cm

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 352 × 320 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

LIGNE ESPACE – TEMPS N° 1 - 2008

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 256 × 300 cm

Dimensions: 256 × 300 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

DETACHEMENT INTERIEUR 2000

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 70 × 80 cm

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 70 × 80 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

REFLETS DE L’EAU N° 1, 2011

Ink on China Paper

Dimensions: 81 × 34 cm

Ink on China Paper

Dimensions: 81 × 34 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

NUAGES N° 3, 2011

Ink on China Paper

Dimensions: 35 × 78 cm

Ink on China Paper

Dimensions: 35 × 78 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

PEINTURE DU 03 N0VEMBRE 2008, 2008

Hommage au Diptyque du Calvaire de Rogier Van der Weyden

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 253 × 100 cm

Hommage au Diptyque du Calvaire de Rogier Van der Weyden

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 253 × 100 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

MUTATIONS ET TRANSFORMATIONS 2000

ETUDE II MARGARETA 2011

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 85 × 111 cm

Dimensions: 85 × 111 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

1. THE STUDIO AS TOOL

The brushstrokes of Fabienne Verdier are something like

corporeal witnesses for that singular instant of a harmonious encounter between

the dynamism of color-material in space and the artist’s bodily awareness of

the present, that instant when, in the deepest concentration of this

awareness—in a radical and exclusive here-and-now—she enters into dialogue with

this dynamism and thereby opens the dialogue to the viewer.

Her studio is built above a spring. A site is thereby

created where telluric energies are particularly perceptible. The canvasses are

spread out on the floor. For Fabienne Verdier, the painterly grounding onto

which she steps is space itself.

Mounted onto an iron beam that traverses the

twelve-meter-high studio are Chinese brushes, huge and ancient. Some of their

shafts are as tall as the painter herself; their bundled hairs can absorb so

large an amount of paint that the weight has to be counterbalanced by their

being hung up. The large brushes are suspended close together from the ceiling.

When disburdened of paint, they begin to sway softly in a pendular dance of

telluric energies; they seem to be alive and to resemble a convocation of

strange beings.

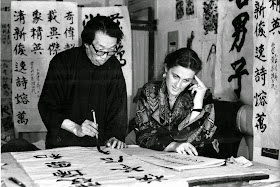

Ever since Fabienne Verdier returned to Paris at the

beginning of the nineties after ten years of study in China, she has constantly

reinvented her tools in order to adapt them to her pictorial ideas. In this

highly individual empiricism, the artist Fabienne Verdier developed an

abstraction of painting that cannot be assigned to any category. The most

important tool for her work is in fact the site of her studio. In this

energetically charged stillness, which made itself felt in an immediate manner

when I stood within this space for the first time, the painterly process

develops as an actual dialogue between the paint material and the forces of

gravitation, the dynamics of adhesion and cohesion, the electric energies of

magnetism, the movements of the earth’s rotation—in other words, it is a

dialogue that arises each day out of completely different circumstances

according to temperature and weather, the position of the sun and the moon, and

the constellation of other planetary orbits. For the paint reacts to heat, for

instance, with extreme agitation, causing the edges to spray upward and fray;

in the case of cold, it is lethargic, adhering more strongly to the canvas. The

entire painterly act in the dialogue between the artist and the brush, the

pictorial space, and the nascent form will be defined by the consistency of the

paint material in response to the meteorological conditions of the particular

day.

If one of the large brushes is soaked with the weight of the

mass of ink, it develops in the sweep of its pendular movement such a force

that this dialogue becomes an extreme physical challenge for the artist. The

more recent, large formats of the canvasses gave rise to a problem that at

first seemed insurmountable. How was it possible, while retaining the highly

concentrated vehemence of the painterly gesture, which is one of the principles

of Fabienne Verdier’s painting, to work in what were now much longer transits

without setting down the brush and reentering the room with a refilled

container of painting material? The maximum ink reservoir of the largest

brushes, which bind together thirty-five horse’s tails, became the

prerequisite. Its being attached to a cable, however, did not in itself

sufficiently reduce the weight of this giant among the Chinese brushes.

The artist violated the great taboo of Chinese art: She cut

off the shaft of the giant brush and had a sort of bicycle handlebar mounted

onto the wooden ferrule of the brush, which was now hung directly from long,

flexible cables. This technical achievement opened up new horizons. The new

mobility now allowed the artist to move through the space of a large canvas

with the same speed that she previously

moved through the space of the smaller formats for which,

logically, lighter brushes are required. This sacrilege is scarcely

comprehensible to an outsider. In spite of such liberation, it is still

important for the artist, who in the eighties studied and lived in China for

ten years, to point out that, even though externally she has severed the axis

of the brush, in no way has she inwardly abandoned the awareness of herself as

being the axis between heaven and earth, for this teaching long ago became her

ethical foundation and center, her discipline and attitude toward the act of

living.3

By her own logic, she has remained true to the Chinese

tradition.

This is demonstrated throughout her entire œuvre, the center

of which, or one should actually say heart muscle, is the “single stroke of the

brush.” Lying concealed here is one of the oldest concepts of Chinese

philosophy, namely the wisdom, attainable only with difficulty, of transposing

a mental or an observed complexity in a single brushstroke. This was the high

art of the venerable masters with whom Fabienne Verdier studied. This was the

reason she stayed for so long in China. Her abstract painting that we have

before us today is accordingly no reduction but, quite the converse, a

compression of all the aspects of an appearance into the very essence of its

existence.

This search also constitutes in its unfolding logic the core

of this text. Although the œuvre of Fabienne Verdier, through her early years

of training, is marked by Chinese philosophy, I will approach this universe

with great freedom from a Western perspective and simply refer here and there

to concepts from Chinese thought, above all when striking analogies emerge

between the two worlds. Out of a concern, however, to avoid reducing the

immense knowledge lying behind every one of these Chinese concepts, I will

limit myself to allowing the individual ideas to merely be hinted at, here and

there, in order to indicate their vast dimensions. What is more important to me

is to demonstrate that it is possible to approach the œuvre of Fabienne Verdier

through Western thought, for that is where the universality of this abstraction

is revealed.

http://fabienneverdier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/essay_doris_von_drathen.pdf

FABIENNE VERDIER'S STUDIO

2. PAINTING AS A MANIFESTATION OF SPACE

All works are preceded by a long mental process and weeks of reflection; a pictorial concept emerges through hundreds of drawings. Even if the material and the movement in space are important elements in this dialogic painting process, the artist decides about pictorial structure and form. But Fabienne Verdier considers her “will to create art” (Kunstwollen)4 not as a subjection of the material and its dynamism, but as her individual artistic discipline of accomplishing an act of painting

in harmonic unison with spatial forces. In the preparatory phase, her will to create art is directed more toward working on the equilibrium of her awareness. For this reason, one could in fact speak of a sort of polyphony that ultimately arises between diverse but reciprocally resonant elements—the artistic activity, the material, and the space as components of a time of dynamic action.

The painting that we have before us does not signify, does not make reference to anything, but instead is a real event in space. The painted traces that we see do not appear because of their form, but instead are real manifestations of spatial energy. And it is precisely here that the œuvre of Fabienne Verdier differentiates itself from the customary categories of abstract painting. The event of these brushstrokes penetrates the consciousness of the viewer like a sonic depth finder. We physically

feel our own groundedness, feel our presentness, our hic et nunc in the flowing, actional texture of space and time.

What we experience is more of a physical-sculptural event. This perspective becomes quite evident when, in spite of the formal differences, one considers for the sake of comparison a small work by Joseph Beuys that, at the beginning of the sixties, he called an Erdding (Earth-Thing).5 This was a wooden construction that he had retained when hammering apart the plaster covering of a Kreuzigung (Crucifixion)

[figs. 2 and 3], an old work from his student days. The title remained as well. Beuys simply attached a thin, tangled wire to the tip of the small, skeleton-like framework. To the wire he tied a thread from which a needle swung freely in space. While the viewer enters into sympathetic contact with this fragile pendulum, he senses deep within himself his own relationship to the magnetism of the earth’s core as indicated by the tiny needle. In its radical reality as a system of physical forces, this “Earth Thing” of Beuys can convey far more about Fabienne Verdier’s painting than any comparison with other abstract painting. For the experience that as individuals we are oriented toward—an innate, indivisible, inalienable gravitation point—is precisely the liberating power that the viewer senses in the paintings of Fabienne Verdier. To experience oneself with reality firmly underfoot, to sense one’s own groundedness, to feel oneself as an independent individual, is to above all and in essence to comprehend one’s autonomous position, one’s autonomous speech and action in this world.

The fascinating spell and deep mystery of this painting cannot be experienced in purely visual terms. A purely rational and intellectual approach would contradict the empirical logic inherent to the œuvre of this artist. Moreover, one of the egregious misconceptions of our era is the belief that visual perception is less physical than all the other senses we use to comprehend the world. The senses are not exclusive; they act in concert.6 The visual faculty is embedded in the totality of our sensory perception. Sound influences our experience of space. Smells can summon up images of remembrance. Looking at pictures can change our mood. Just as we experience the spatiality of our environment with our entire physical existence, so does the viewer likewise discover the actual dimensions of the visual world of Fabienne Verdier through the complex apparatus of a comprehensive sensory perception. After Kant 7

and Hegel,8 who were the first to attempt to overcome the old Aristotelian gap between the senses and the mind, and who refuted Descartes’ ideas of contrasting

corporeality and mentality, there is no one more radical than Feuerbach in the formulation of this notion of a reevaluation of physical perceptions when he states: “The secret of direct knowledge is sensory awareness.”9 Elsewhere he insistently emphasizes: “[…] the mental is nothing without the sensory.”10 He thereby sets up an equation between the sensory and the mental that he characterizes as “essence, as the mind of the senses.”11 This reevaluation finds an echo in contemporary French philosophy with the great concept of the sensible, which Emmanuel Levinas primarily

developed and Jacques Rancière12 elaborated further. For Levinas, however, the concept of the sensible was the point of departure for his philosophy of an ethically based ontology. For it was precisely in sensory cognition, which is able much more than rational cognition to transcend simple experience and to attain a mental-sensory horizon of experience, that Levinas saw the prerequisite for encountering the Other beyond one’s own conceptual borders.13

But indeed, this is what constitutes the very essence of a work of art—the fact that it is an ontological event that confronts us with the Other. Aby Warburg even speaks of two energetically charged poles—that of the work of art, and that of the viewer. It is between them, in the electrically charged, magnetic field of their energies that the work of art first comes to being—not as an object, but in fact as an ignition, as something unseizable, as a flame.14 Only after this sensory, emotional event can the

logos arise, can a commentary begin. Not all artists are capable of creating presences that induce, shock, and trigger such a comprehensively evocative experience. Fabienne Verdier is one of these select few artists.

One of the exceptional aspects of Fabienne Verdier’s painting is the fact that she does not align her work with an aesthetic discourse but instead speaks about her œuvre within the terminology of astrophysics. Verdier has a self-evident awareness of being part of the cosmos, of being made of matter. In actuality, her painterly dialogue means breaking the age-old monopoly of the human being’s claim to be the sole artist; instead it recognizes nature as an artistic partner. For her, the dialogic painting

process means living in distinct awareness of a correspondence with the universe. The artist conceives of herself as a being who is connected at every moment with the evolutionary process of the cosmos and who, just like matter, resonates with the movements of the earth and the lunar cycles. The painter sees herself as part of the constant ebb and flow, the ceaseless transformation of matter.

http://fabienneverdier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/essay_doris_von_drathen.pdf

FABIENNE VERDIER NOTEBOOK

3. THE COSMOS AS STANDARD OF MEASUREMENT

In this studio, an art historian must unlearn very

much indeed. For instance, my method of working with iconology in contemporary

art and, in the wake of Warburg and Panofsky, of inquiring after sense and

images, possibly after invisible images of thought, here meets up with its own

limitations.15 But it is possible to think in analogies, for physical processes

and geometric forms contain a metaphysical level of understanding that is in

turn universal. Here and there it accordingly seemed relevant to reflect the

Chinese-influenced thinking of the artist not only in philosophical or literary

terms, but also in terms of the natural scientific resources of the West;

surprisingly, Leibniz became an important point of reference. Particularly

illuminating for connections between painterly and cosmic processes were, for

instance, the fractal theories of Benoît B. Mandelbrot, or the thoughts of

Edgar Morin, known for his transdisciplinary studies combining philosophy,

sociology, and the natural sciences, who begins his essay L’identité humaine

with the challenging demonstration of his thesis: Le cosmos nous a créés à son

image. (The cosmos created us in its image.)16 The facts, however—that this

abstraction, which for us is so new and unusual, is based on age-old wisdom;

that as a border crosser between East and West, Fabienne Verdier combines the

teachings of the ancient Chinese masters with her models from the Italian and

Northern Renaissance; that as a painter she works with sculptural and spatial

principles—make it almost impossible to compare her œuvre with the works of

other contemporary painters.

There are, perhaps, exceptions in the case of artists

such as Pat Steir who, for her part, was influenced by sojourns in China and

who likewise works with the gravitation of flowing paint, or as she herself

says, with the “nature of painting.” But Pat Steir17 works in front of vertical

canvasses and with the clear awareness of creating a pictorial illusion. What

is similar, however, is the fact that Pat Steir as well sees her own painting

as a touchstone and a teacher for both her art and her life discipline. Her own

role model was Agnes Martin; the two were linked in a lifelong friendship.

Agnes Martin as well was able to realize complex observations and sentiments

with regard to nature in a few bands of color, to create compositions that

resemble orchestral scores and certainly have nothing to do with minimalism,18

but instead with a highly personal search for an essence. A generation younger,

Fabienne Verdier extends this search even further, in as much as she radically

elevates the unison of her consciousness with the energies of the cosmos into a

criterion for her painting. She compares her own breath, which accompanies each

of her gestures, with the breath of the space, with its flowing energy. It is

crucial for her that these movements harmonize. Every deviation is not only

visible for the artist, but palpable. Up to ninety percent of her paintings are

filtered out. For Fabienne Verdier, an archaic purification belongs to the

painting process: She burns the sorted-out pictures. A special place is set up

for this purpose on the grounds of her studio; from her perspective, the

failure of an unbalanced brushstroke is negative energy which, in her

understanding of the world, could have a disturbing effect on her own further

work and on the viewer. Here, in spite of all formal differences with the world

of Fabienne Verdier, a connection seems to be established to Shirazeh

Houshiary, who paints from Islamic psalms, which she inscribes onto her

canvasses while singing them aloud, and by so doing creates pictorial

intensities that are based above all on a contemplatively balanced rhythm of

the breath.19 What is comparable is, on the one hand, the highly developed

awareness of the fragility of concentration upon an absolute harmony and the

great risk of its disturbance; and on the other hand the belief that the breath

flows, not just through the human body, but likewise through the cosmos. In the

worldview of Fabienne Verdier, the essence of all things lies in this flowing

breath. The artist has in mind here the breath of matter itself, which in

movement and in flight actually renders visible air, space, and emptiness, as

if the forms were intended only as a pretext, a stage setting as it were, for

these blancs volants, 20 the flying void that is a vital part of matter and the

main theme of this manner of painting. At the same time, however, the artist

also makes reference to sound here, often that of her own voice, which

imitatively follows great pieces of choral music and accompanies her painting

as rhythmic, breathed music. It is characteristic of only a few artists, most

of whom are sculptors, not only to contemplate the correspondence between

cosmos and body, but to develop out of this awareness a conception of space

that in fact includes the vastness of the heavenly expanses in artistic

creation. Were one to select from among these artists, the individuals who

actually make telluric energies an element of their work, a small group would

emerge which, if one leaves behind the borders of formal categories and instead

dares a transversal contemplation of art, has strong similarities with Fabienne

Verdier.

To be cited from this perspective, as we have already

seen in one example, are the energetic conceptions of Beuys. Fred Sandback’s

œuvre [fig. 4], with its woolen threads, which are stretched freely in the air

and whose intermediate spaces induce in us the experience of immaterial walls,

could be revealingly set alongside the painting of Fabienne Verdier.

Comparative aspects could emerge in the sculptures of Richard Serra when we

become aware of our being-in-space through such works as the Torqued Ellipses

,21 [fig. 5] which he began in 1997, or when, as in the work Promenade [fig. 6]

from 2008,22 he causes the space within us to resonate with the thin,

vertically standing steel panels through which he measures out the rhythmic

accents of a specific space. In this quite free correlation of a spatial

awareness, analogies may be seen between the extreme presence of the strokes of

the brush in the paintings of Fabienne Verdier and The Lightning Field [fig.

7a-b] of Walter De Maria, who ushers into experience not only the impossibility

of grasping hold of the present, but also the charged energy of space itself.

To be mentioned in this con - text are Rebecca Horn, who gives consideration in

her entire œuvre to the flowing energies of the cosmos and its dimensions, or

Anish Kapoor, who knows that the high precision of geometrical forms and of

physical laws are capable of inducing a contemplative stillness in the viewer,

as in the work At the Hub of Things [fig. 8] from 1987. The artist Kimsooja

causes this precision to be felt when, in her performances, as for instance A

Laundry Woman, she turns her own body into a seismograph; in channeling these

energies she compares herself to a “needle,” a vertical axis space [fig. 9].

Max Neuhaus [fig. 10] likewise works with an awareness that his invisible sound

sculptures are embedded within a cosmic space and cosmic time. He brought this

insight to expression with a work from 200723 that makes it possible to

experience the contrast of different temporal calculations inside and outside

the synagogue, and thereby takes as its actual theme the incomprehensible time

between individual divisions of the day. This surrounding field of sculptors

seems to me to be far more suitable for finding resonances with the work of

Fabienne Verdier than a comparison with other painters.

The logic of my comparison lies beyond the formal

perspectives of aesthetics and instead pertains to the consciousness with which

the a fore mentioned artists work—namely the awareness of being directly

positioned in the energy field between earthly ground and heavenly dome, and of

integrating the viewer into the transcendent expanse of this experience.

Precisely this is the event in the painting of Fabienne Verdier. When her

corporeal brushstrokes all at once rip apart the dynamic flow of the plexus of

space and time, the artist awakens with an abrupt shock our awareness of

ourselves as embodying this sort of present, an existence amid constant

becoming that changes at every instant, which itself flows and is thus a part

of the ceaseless current of cosmic evolution. Like a mighty sound or a blow to

the forehead, the painting impacts the viewer, who gradually comes to feel its

effect—if he allows himself to.

http://fabienneverdier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/essay_doris_von_drathen.pdf

FABIENNE VERDIER NOTEBOOK

FABIENNE VERDIER'S STUDIO

I .THE WORLD IN A SINGLE POINT

When Leibniz, who with no little pride considered

himself to be a “painting mathematician,”24 was commissioned by his ducal

sponsor to design a signet ring, he was confronted with a crucial challenge.

What was required was the representation of a cosmogony in a formulaic diagram.

His deliberations were accompanied for years by an exchange of ideas through

lively discussions and regular letters. The drawing that Leibniz ultimately

submitted in the year 1697 as the final version was nothing less than the beginning

of the Enlightenment. His diagram [figs. 12a and 12b] showed two concentric

circles and a distinctly marked point in the center. In the emptiness between

the rings, he had written the sentence Unum ex nihilo omnia bene fecit (The One

made everything well out of nothing.) By changing one single letter, Leibniz

had taken leave of the centuries-old tradition of religious worldviews. Valid

up to then in the Europe of the Renaissance, general assent had been granted to

the motto: Unus ex nihilo omnia bene fecit, namely “One (i.e. a divine creative

principle) made everything well out of nothing.” Leibniz, on the other hand,

replaced the grammatical subject with Unum, the number One, i.e. the rationally

experienciable.

In the commentary to his diagram, Leibniz had

explained that in his eyes, the void and the point in its middle best expressed

One and Zero.25 The cosmogony he proposed was nothing less than a formula for

the universe of the dyad, the binary system that even today is the basis for

computer programs. With his shifting of Unus to Unum, however, Leibniz remained

circumspect and declared the number One to belong to the “things created by

God.”26

The Inquisition was still active; the execution of

Giordano Bruno was a little less than a hundred years past. For Leibniz it was

dangerous enough to claim that he saw the essence of all things in the numbers

One and Zero.27

But with the shift from Unus to Unum, in other words

from a creative principle to something created, to something that could be

comprehended by human understanding, which could be considered as a principle

of the origin, Leibniz conceived of a connection, astounding even today,

between mythic and scientific thought. Implicit in this tiny diagram is a

bridge between the religious and the rational world. But did Leibniz know how

closely his diagram is related to the Chinese tradition of the bi? These

ancient, flat jade discs with a circular hole in the center have possessed, for

thousands of years and in a surprisingly comparable manner, the meaning of

cosmogonies at whose center are at work forces of change that maintain space

and living beings in states of constant transformation.28

http://fabienneverdier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/essay_doris_von_drathen.pdf

PEINTURE DU 2 SEPTEMBRE 2014

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 150 × 365 cm

Dimensions: 150 × 365 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

SERIE WALKING – PAINTING, SOLO N° 04, 2013

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 134 cm

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 134 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

SERIE WALKING – PAINTING, QUADRIPTYQUE N° 01, 2013

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 536 cm

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 536 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

SERIE WALKING – PAINTING, TRIPTYQUE N° 05, 2013

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 402 cm

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 402 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

SERIE WALKING – PAINTING, TRIPTYQUE N° 07, 2013

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 402 cm

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 402 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

SERIE WALKING – PAINTING, SOLO N° 02, 2013

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 134 cm

Ink on Paper "Moulin du Gué"

Dimensions: 198 × 134 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

POLYPHONIE, ASCESE, 2013

Les Vitraux de "La Vierge au Chanoine Van der Paele"

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 7,35 × 4,07 m

Les Vitraux de "La Vierge au Chanoine Van der Paele"

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 7,35 × 4,07 m

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

POLYPHONIE, ASCESE,

INSTALLATION IN MEMLING MUSEUM 2013

Les Vitraux de "La Vierge au Chanoine Van der Paele"

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 7,35 × 4,07 m

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 7,35 × 4,07 m

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

POLYPHONIE 2011

Les Vitraux de "La Vierge au Chanoine Van der Paele"

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 183 × 408 cm

Les Vitraux de "La Vierge au Chanoine Van der Paele"

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 183 × 408 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

FENETRE SUR L’INFINI N° 2, 2012

Oil Pastel on Dyed Arches Vellum

Dimensions: 54 × 38 cm

Oil Pastel on Dyed Arches Vellum

Dimensions: 54 × 38 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

FENETRE SUR L’INFINI N° 3, 2012

Oil Pastel on Dyed Arches Vellum

Dimensions: 54 × 38 cm

Oil Pastel on Dyed Arches Vellum

Dimensions: 54 × 38 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

FRESQUE TORLONIA, OPUS I -

2010

Installation of Two Frescos in The Palazzo Torlonia, Rome

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 407 × 763 cm

Installation of Two Frescos in The Palazzo Torlonia, Rome

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 407 × 763 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

FRESQUE TORLONIA, OPUS II -

2010

Installation of Two Frescos in The Palazzo Torlonia, Rome

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 407 × 757 cm

Installation of Two Frescos in The Palazzo Torlonia, Rome

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 407 × 757 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

L’HOMME EN PRIERE I -

2011

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 181 × 121 cm

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 181 × 121 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

L’HOMME EN PRIERE II -

2011

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 181 × 121 cm

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 181 × 121 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

INTENTION III ANDANTE - 2004

Pigments and Ink on Canvas in Linen - Cotton

Dimensions: 136 × 160 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

BLACK CIRCLE 2006

Serigraphy Printed in 8 Colours

Dimensions: 111 × 76 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

PELERINAGE AUX MONTS DES INTENTIONS 2006

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 135 ×160 cm

Musée National d’art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 135 ×160 cm

Musée National d’art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

BRANCHE D’EVEIL 2004

Série : "Essence Végétale"

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 109 × 46 cm

Série : "Essence Végétale"

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 109 × 46 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

CHARPENTE D’ARBRE 2004

Série : "Essence Végétale"

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 45 × 40 cm

Série : "Essence Végétale"

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 45 × 40 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

MATURARE N°16, 2009

Ink on Chinapaper

Dimensions: 42 × 56 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

SAINT CHRISTOPHE TRAVERSANT LES EAUX I - 2011

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 244 × 135 cm

Dimensions: 244 × 135 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

SAINT CHRISTOPHE TRAVERSANT LES EAUX III - 2011

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 180 × 365 cm

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 180 × 365 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

ETUDE II MARGARETA 2011

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 85 × 111 cm

Dimensions: 85 × 111 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

MELODIE DU REEL I - 2014

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 183 × 135 cm

Ink, Pigments and Varnish on Canvas

Dimensions: 183 × 135 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

BRANCHES ER BOURGEONS ‘’ETUDEDUVEGETAL‘’ - 2010

Serigraphy Printed in 9 Colours

Dimensions: 150 × 124 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

LE MONT DES IMMORTELS 1993

Cobalt Ink and Cinnabar Seals on Silk Canvas

Dimensions: 38 × 25 cm

Cobalt Ink and Cinnabar Seals on Silk Canvas

Dimensions: 38 × 25 cm

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

MEDITATIONS EN COBALT 1997

Homage to Variations Without a Theme of Yehudi Menhuin

Cobalt Ink, Pigments, Varnish and Cinnabar Seals on Silk Canvas

Dimensions: 180 × 260 cm

Musée Cernuschi Collection, Paris

Homage to Variations Without a Theme of Yehudi Menhuin

Cobalt Ink, Pigments, Varnish and Cinnabar Seals on Silk Canvas

Dimensions: 180 × 260 cm

Musée Cernuschi Collection, Paris

© 2014 Fabienne Verdier

1. THE CIRCLE AS AN OPEN QUESTION

This empty center fascinates the viewer in a long,

constantly expanding series of paintings that have long accompanied the œuvre

of Fabienne Verdier. The concentrated space, which is indicated here by the

rotation of a brushstroke and is almost but not completely enclosed, is charged

with such dynamic energy that all at once every reference to minimalism or

classical abstraction is rescinded.

Fabienne Verdier entitles this work from 2007 Cercle

blanc (White Circle) [fig. 11]. The painting measures 1.85 meters by 1.5

meters. For this format, the artist works with Chinese brushes whose shafts are

almost as tall as she is. She stands in the middle of the canvas and executes

the rotational movement with the strength of her entire body. The heavy impact

of the brush is evident in the thickening of the black ink; spray marks running

across the empty center of the circle give clear testimony to the entry of the

large, vertical brush into the space of the white canvas. The speed of the

sweeping brush is attested to by the tearing away of the painterly gesture, and

by the abruptly gaping hatchings modeling the void when the ink could not

adhere amid its flight. Like a gust of wind, these blancs volants streak

through the paint material. These manifestations of space belong to the act of

painting in a form-constituting manner. What is more, the void—or in the

language of Fabienne Verdier, the breath—is an element of this painting, just

as are brush, paint, and the dialogue with the telluric forces.

The openness of the circle, however, allows the void

and the space to flow further, as if the question concerning this space had to

remain unanswered, as if the mystery of this question could not be permitted to

be reduced. Two lengths of the arm constitute the diameter of the trace of ink,

which has lost its materiality in the dynamism of its flowing movement, so that

the white space comes to define the form more and more. Just as its title says:

Cercle blanc.

This event of a circle in space could evoke the light

sculptures of Anthony McCall when, for instance, he causes a circular line to

grow out of a point of light upon a dark projection surface. In contrast to the

vehement statement of Fabienne Verdier, Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone

[fig. 13] from 1973 grows with extreme slowness. But the emergence of this

projected circular line forms a substantial, conic volume that arises out of

fog-enriched rays of light and through which the viewer can pass. This light

sculpture by Anthony McCall is cited here for comparative purposes, for it

allows the visual, even haptic experiencing of the spatiality of a line. The

viewer experiences this spatiality in the painting of Fabienne Verdier, when

the trace of its flight overcomes the heaviness of its materiality and is only

wind, only hovering emptiness and rotation that manifests in the instant of its

embodiment in space. Automatically the viewer senses the energy-charged void

that is held by this furious, scattering brushstroke. Automatically we sense

that here the manifestation of the circular movement ushers the space itself

into presentness.

For Fabienne Verdier, the mystery of this space and

its all encom - passing vitality seems to be too profound to be designated with

names or images. In contrast to the great tradition of philosophers,

scientists, artists, poets, and sages who endeavor to fill this gap, this limit

of human understanding, with mystical and religious concepts, she causes the

void itself to appear in her painting. The emptiness of Cercle blanc could be

equivalent to a silence, a non-utterance, possibly a question. In accordance

with this logic, it makes sense that a complex of works with the title Cercle

ascèse I–IX (Asceticism Circles I–IX) is designated by the term Silencieuse

coïncidence [fig. 14] (Silent Coincidence). The actual reality is omitted. The

question as to the vitality, the breath of the space remains open, just like

the circling track of the brush itself.

Thus when in the same year Fabienne Verdier actually

paints a polyptych that she calls L’Un (The One, 2007) [fig. 16], a title that

in French does not define the difference between Unus and Unum, it would

contradict her working logic to introduce into the painting that which she

explicitly conceals there as Silencieuse coïncidence .

In a single stroke, the track of a brush, almost half

a meter wide and two-and-a-half meters long, traverses the space vertically. In

its radical dynamism, the gesture is reminiscent of Fontana. Here as well, a

breach seems to have been made; the constancy of the energetically charged,

flowing texture of time and space seems to have been slashed open; a current

coming into existence seems to emerge radically as a painful event of piercing

through this continuum. But in contrast to the incision with which Fontana

[fig. 15] transforms the canvas into three dimensionality, Fabienne Verdier

creates the three-dimensionality of her brushstroke through a sculpturally

haptic application of paint whose edges bear witness to the movements of the

brush in irregular vitality, whose surface is pervaded by tiny fissures, as if

this mode of painting, tantamount to a global landscape, were subject to

geological evolution and were continuing to change in constant movement.

The title of this single painted track, which

traverses a pictorial space of six canvasses in a 50-by-116-centimeter format,

indicates precisely this—the trace of a brush which, as a single stroke,

embodies with instantaneous intensity the presence of its emergence.

The weight of this stroke clearly lies at the upper

end. The movement of the brushstroke proceeds from this impact of the brush,

which initially gathers all the energetic impulses into a moment of rest: first

powerfully, then dwindling away. With scarcely a further visual echo when the

ink reservoir of the brush is emptied, its cluster of hairs causes the flow of

material to be disrupted and to thin into transparent hatchings, and the

dynamism of this stroke ultimately fades away in the space.

The painting L’Un was created on the day when the

cellist Rostropovich died, on April 27, 2007. As is so often the case, Fabienne

Verdier dedicated her painterly act to a certain moment. Observations of

nature, contemplations of pictures, words of a philosopher, poet, or scientist

that impart joyous or dramatic movement: these can be the inducement for

exploring the complexity of an impression or a thought and transferring it as a

“tribute” into a single, jubilant stroke of the brush. Thus the individual

brushstroke is also a contemporary witness.

The viewer, above whom this polyptych of a single line

towers by nearly the height of his own body, automatically raises and lowers

his head when he follows the movement of the pictorial trajectory. With his

body, he automatically traces out the actual force of this painted track, not

only the vertical movement of the spatial axis, but above all a vigorous,

liberating exhalation.

Indeed, this movement of the breath, which as a

flowing column streams vertically through the human body and thereby through

the space, seems to be manifested in this line. This becomes evident upon

closer inspection. Two elements refer directly to the process of creation. The

segmentation of the canvas points to the intermediate spaces that play just as

important a role during the painting process as the corresponding, empty inner

space of the large brush. Its interior is shaped so as to create an actual

tank, a reservoir that can hold up to one hundred liters of paint material.

Important empty spaces are created by the distances between the segments of

canvas, which are stretched across reinforced wooden-frame constructions and

lie raised somewhat upon the floor, so that excess material can drain away. The

geometrical arrangement of the canvas segments—which, as measured-out,

controlled, and controlling lines, impart a regular rhythm to the freely set

brushstrokes, painted traces, and their accompanying flight of

drops—accordingly has a purely functional significance.

The radical presentness of this corporeal trace of the

brush requires a powerful vehemence in the painterly gesture. The paint

material, however, which is transported by a fully soaked horsehair brush, has

so massive a weight that the sharpest control could scarcely keep it from

spreading spontaneously across the entire surface. Thus the intervening spaces

of the canvas segments support the physical resistance of the handling of the

brush. For its part, the reinforced wooden structure guarantees that the artist

can stand or run upon this painting surface, as well as fight against the

dynamism of the massive material with the entire, erect power of her body

without bursting apart the canvas. The purpose of this detailed description of

the actual painting procedure is not to emphasize the process of creation itself

as a theme, but to show the radical pragmatism of a way of thinking.

The second element giving an indication of the

developmental process is the airy track of splashes and drops that begins in

the lower area of the canvas, disappears behind the brushstroke, reappears on

the side describing a parabolic flight, and joins the upper heaviness of the

line. The beauty of these merrily dancing splatters is in turn simply an

unavoidable inclusion of the process of creation.

http://fabienneverdier.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/essay_doris_von_drathen.pdf

You may read whole essay to click above link.

FABIENNE VERDIER

by Doris von Drathen

Fabienne Verdier is a border-crosser between several worlds:

Chinese old masters and painters of the Italian and Northern

Renaissance; at the same time however she emphasizes a radical pragmatism

which, shows similarities to the twenty years older Post-Minimalist generation.

Born in 1962, the artist is one of the youngest abstract

painters working today. Inasmuch as she has created a sculptural mode of

painting, it is nearly impossible to compare her oeuvre with that of other

painters. But one could say that Fabienne

Verdier’s attitude basing her life on Asian discipline

inscribes her in the field of thinking and painting of the American artists

Agnes Martin and Pat Steir.

Although Fabienne Verdier studied painting and philosophy in

China for ten years, she developed her own, radically new abstraction. Her

painting does not represent anything, but instead creates a manifestation of

telluric forces. With the method of the single brushstroke which is the center of her

work, she searches for more than abstraction, seeks out the essence of all

things. In this same logic, the space of the canvas does not represent a

pictorial space, but is real space, influenced by the same

cosmic forces as is our own vital space.

Thus the painting with which she achieved her breakthrough

in the international art world is titled L´Un (“The One,” 2007). In fact,

this title alludes to nothing else than the uniqueness of that brushstroke

which, in its deepest enigma, is similar to the enigma of the essence of all

things. This painting was placed next to works by Rothko, Pollock, and Richter

during the exhibition Art of Deceleration at the Museum Wolfsburg in

Germany.

A crucial painting in that same year of 2007 was Cercle Blanc (“White Circle”), which showed

the importance of the void and the

energies of breathing: those of the painter herself during her act of painting, and those of

space, which she transverses with the

brush. Evidence is provided here that Fabienne Verdier transforms the material into a

support of the void.

A series of paintings were the turning point in Fabienne

Verdier’s oeuvre: Ligne

Espace-Temps – Line through Time- Space (2009). These were paintings

which, for the first time, made it necessary to traverse huge spaces with one

“tank” of ink, without interrupting the line. With the radical pragmatism of

these new conditions, Fabienne Verdier cut the handle of one of her biggest

brushes composed of 35 horse tails and had it mounted under the ceiling of her

12 meter high studio. To break this taboo and severe that handle, as tall as

herself, was her definitive liberation from the Chinese tradition, even though

she states that the vertical axis and its philosophical

discipline will always be alive in her mind and body.

This was the basis for giving birth to a new dimension of

painting. Celebrated in Italy in 2010 were two walls of “frescoes” in the

Palazzo Torlonia in Rome: Two polyptychs each 4 m in height and 7m50cm in

length had been created with this newly mounted brush, which offered much more

mobility “in space.” Another polyptych of 2m50cm x 6m33cm was dedicated to the

drama of the tsunami and in fact showed our

helplessness in facing the forces of nature.

This radical work of a condensed complexity―which could be a

thought, an observation of nature, a piece of music, or a drama of

humanity―found its limit in confronting the highly detailed paintings of the

northern Renaissance at the museum

of Bruges, where Fabienne Verdier will exhibit a dialogue

with her paintings in March 2013. Sometimes a detail like tiny, leadframed

windows could inspire the artist to amazing polyptychs of huge dimensions: Polyphonie is one of them which gave rise

to a new mode of thought, transforming the void, the

breathing into the energy of voice.

All the paintings of Fabienne Verdier have this in common:

Even though they might appear to be spontaneous gestures, the act of painting

is very slow and highly premeditated, prepared by hundreds of elaborate

drawings and by a reflection mirrored in series of notebooks. And they all have

this in common: Being a manifestation of telluric forces, they―in spite of

their abstraction―are a cosmic reality of their own, an absolute presence which

awakens in us the consciousness of our own presence in space.

www.fabienneverdier.com