MODERN PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE THOMAS WALTHER COLLECTION 1909 - 1949

MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK

December 13, 2014 - April 19, 2015

MODERN

PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE THOMAS WALTHER COLLECTION 1909 - 1949

MUSEUM OF

MODERN ART NEW YORK

December 13,

2014 - April 19, 2015

The Edward Steichen

Photography Galleries, third floor

Exhibition

Coincides with the Culmination of the Thomas Walther Collection Project, a

Four-Year Research Collaboration Between MoMA’s Curatorial and Conservation

Staff

Explores

photography between the First and Second World Wars, when creative

possibilities were never richer or more varied, and when photographers

approached figuration, abstraction, and architecture with unmatched imaginative

fervor. This vital moment is dramatically captured in the photographs that

constitute the Thomas Walther Collection, a remarkable group of works presented

together for the first time through nearly 300 photographs. Made on the street

and in the studio, intended for avant-garde exhibitions or the printed page,

these objects provide unique insight into the radical intentions of their

creators. Iconic works by such towering figures as

The exhibition

coincides with Object:Photo. Modern Photographs: The Thomas

Walther

Collection 1909–1949, the result of a four-year collaborative project between

the Museum’s departments of Photography and Conservation, with the

participation of over two dozen leading international photography scholars and

conservators, making it the most extensive effort to integrate conservation,

curatorial, and scholarly research efforts on photography to date. That project

is composed of multiple parts including a website that features a suite of

digital visualization research tools that allow visitors to explore the

collection, a hard-bound paper catalogue of the entire Thomas Walther

collection, and an interdisciplinary symposium focusing on ways in which the

digital age is changing our engagement with historic photographs.

Modern

Photographs from the Thomas Walther Collection, 1909–1949, is organized

thematically

into six sections, suggesting networks between artists, regions, and objects,

and highlighting the figures whose work Walther collected in depth, including

André Kertész, Germaine Krull, Franz Roh, Willi Ruge, Maurice Tabard, Umbo, and

Edward Weston. Enriched by key works in other mediums from MoMA's collection,

this exhibition presents the exhilarating story of a landmark chapter in

photography’s history.

http://www.moma.org/visit/calendar/exhibitions/1496

A BASIS

FOR COMPARISON: THE THOMAS WALTHER COLLECTION AS RESEARCH COLLECTION BY

JIM CODDINGTON

What is it? What is an object, a particular work of

art? This question, which lies at the heart of art-historical inquiry, is

itself comprised of others: who made this object? When? Where? What is it made

of? The study of archival materials that relate to an artwork, such as

provenance, exhibition records, and written accounts by contemporaries and

historians, is vital to such investigation, but initially, how the

arthistorical object is defined by these questions is an empirical problem,

which is derived from observation of the object itself. Once we start to answer

these basic questions, we can begin to place the object in the larger

art-historical narrative and scholarship—a process that is the result of

comparing these answers to those derived from other objects, other artists,

other periods. Indeed, the reflexive use of comparisons seems as fundamental to

art-historical inquiry as the description and analysis of objects, even when it

is not explicitly recognized as such.1 Comparative analysis is thus central

to art-historical inquiry, and it is a core methodological principle as well

for conservation and conservation science, both of which play a significant

role in characterizing the art object itself and in classifying it relative to

its place in the art-historical context, as is evident here in the collective

research conducted as part of the Walther project. These qualitative and

quantitative analyses not only help us to better understand the specific

artworks themselves (in this case, photographs [fig. 1]), they also form a

basis for comparisons with other works by the same artist, other works within

the collection, and works across multiple collections as well.

Conservation and conservation science often bring particular methods and sets

of data to the task of arthistorical investigation. For instance, observation

of works by the same artist reveals patterns of material use as well as

technique in using those materials, while deeper research on the particular

object can include direct analysis of its materials to establish their chemical

composition and physical performance. Knowing what paint Jackson Pollock used

is critical to identifying his works, for example, and also to the

understanding of his development of a distinctive style that placed him well

outside the norms of historical painting practice.2 More subtly, a better

knowledge of the white pigments employed by Piet Mondrian can enhance our

insight into the effects one sees in his paintings by understanding the

fundamental properties of those pigments.3 Such information is derived from

instrumental analysis of microscopic samples taken from the work or,

increasingly, using instruments that collect data directly from the work

without sampling.4 Material comparison can be critically important in the

medium of photography, where original artworks often exist as multiples that

are sometimes created years apart using the same negative but printed with

different materials and artistic intentions, such as is evident in examining

Edward Weston’s switch from platinum to gelatin silver printing, a key

transition in his artistic development. Essential to such analysis is, once again, the use of

comparative data, not only from works by the specific artist but also from

reference collections of materials, which are a fundamental and invaluable

resource. Reference collections of art materials are, by definition, material

samples of known provenance. Often the reference collection, the material

archive, will also contain analytical data of some kind for comparison by other

researchers analyzing similar material samples.

Material

archives have long been a part of conservation research, one of the first being

the Forbes Collection. Begun around 1910 as a collection of historical artists’

materials to support Edward Waldo Forbes’s course on Italian painting at

Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum, today samples from the Forbes pigment collection

reside not only at Harvard but at numerous other institutions; taken as a

whole, the collection represents an essential attribute of all truly valuable

reference collections, which is a provenance of the sources of the samples

themselves.5 Although the Forbes Collection is known principally as a pigment

collection, it is in fact broader than that, comprising samples of artists’

materials such as historic paint media and varnishes as well. In addition, the

collection of pigments has come to serve other research uses beyond its initial

purpose as a reference to study Renaissance Italian painting. Because the

collection was built during the first half of the twentieth century, it can

also be viewed and used as an archive of pigment manufacture during that time.

It thus offers comparative data for the history of pigment making and a

resource for comparing pigment samples from objects made during that period,

demonstrating that material archives can often find applications beyond the

vision of their original creators. Particularly useful have been those

reference collections dedicated to paper, such as the one at the National

Gallery of Art. A prime value of such paper collections is the identification

of watermarks as a means to date the paper as well as the maker. The material

constituents of a paper collection, such as the fiber content of the individual

papers (fig. 2), have become increasingly valuable as analytical equipment and

techniques to aid such characterization have become more commonly available to

the conservation field, as demonstrated here in the work of Hanako Murata and

Lee Ann Daffner.

Indeed, this increased analytical capacity and

sophistication have expanded the idea of the reference collection to include

not only materials of well-documented provenance but data collections of

well-documented provenance as well. The Infrared & Raman Users Group (IRUG)

is one of the oldest and most widely used of such collections, in which the

material sources and analytical protocols for deriving the data are both

clearly detailed.6 The IRUG collection of reference data is not deposited in a

single place but rather is a searchable database from which members can compare

their analytical results to the reference materials and the data in the

database. For instance, if there is an adhesive or coating on a work, a sample

can be analyzed via infrared spectroscopy, and similar spectra are then called

up for comparison to identify the closest match. This would be one of the approaches to identifying the

paint Pollock used in the example above. It is worth noting that such analysis

is not simply a mechanical process or computational result but one that

requires a degree of judgment. Differences in results can be due to an unknown

element in the sample, deterioration or aging of the material of interest, as

well as differing protocols, sampling techniques, or sensitivity of the

detection method itself, all further evidence of the critical role of data

interpretation by experienced scientists in rigorous material studies.

It is

fortunate that reference collections that make use of sophisticated analytical

tools have been incorporated at roughly the same time that the range of artist

materials has started to increase exponentially. Synthetic polymers, singly and

as constituents in complex formulations or as composites, have been present in

the work of artists for much of the twentieth century. The task of

characterizing this huge universe of materials is daunting, and conservators

and conservation scientists routinely turn to industrial literature to acquire

key data and research information. Industrial paint literature has been central

to characterizing the paints used by many modern artists, for example.7 The

photographic film and paper industry, a truly modern phenomenon as well, was

for many decades one of the most extensively researched and recorded, due to

the size of the market for these materials and their general penetration not

just into fine-art collections but into the culture at large. Certainly

when it comes to furthering our materials based understanding of the history

and development of the photograph as an artistic medium, the Messier Collection

of photographic papers is critical, a fact amply illustrated by Paul Messier’s

contribution to this project. Consisting of more than 5,000 paper samples, this

material archive offers researchers the opportunity to probe in numerous ways

the complex medium of photographic papers, from early in its commercial history

to the late twentieth century, thus providing an incomparable resource to

better establish how, when, where, and by whom fine-art photographs were made.8

The Messier Collection has been a fundamental tool for the research conducted

on the Walther Collection, both directly and through the utilization of past

research based on the collection. Protocols from that prior research, as well

as other protocols, have been incorporated into the examination and

instrumental analysis of the photographs in the Walther Collection. These

include elemental analysis of the baryta and emulsion layers using X-ray

fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF; fig. 3), thickness measurements (fig. 4),

Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), texture imaging (fig. 5), gloss

assessment, and UV fluorescence of the photos. The Museum of Modern Art’s

film stills archive represents another material collection that has greatly

benefited efforts to better characterize photographs. Consisting of more than 4

million individual stills and promotional materials from the United States,

England, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Asia, and from the earliest days

of the film industry to the present, the collection is another example of one

that was originally acquired for historical and documentation purposes (in

this case, surrounding the history of movies) but is now valued for its

material information as well. This collection, with well-documented printing

dates for the photos, has been used to refine a methodology for dating

photographs, and these research methods have also been central to the

characterization of the photographs in the Walther Collection.9 Such deep

characterization of the material constituents of the entire collection thus

brings the Walther Collection, in addition to its art-historical importance,

into the realm of the kinds of material archives and research collections

outlined above. The research methods are clearly detailed and public. The

photos themselves are well documented, with substantial provenance and

historical research supporting them.10 The collected data, both art historical

and scientific, can be a source of comparison for other researchers who have

derived their own data through their study of similar photographs or other

works by the same photographer. More broadly, the methodologies from this

research can be applied to other photographs and photography collections, which

in turn will further extend the field’s global set of data so that new comparisons

leading to new characterizations and classifications of photographs can be

made. And, like other such collections, the research on the Walther Collection,

both material and arthistorical, will be extended and expanded in the future,

offering ever more comprehensive understanding of the collection itself, its

photographers, and the vital period of photography it represents—in sum, what

each of these photographs is.

t

https://www.moma.org/interactives/objectphoto/assets/essays/Coddington.pdf

https://www.moma.org/interactives/objectphoto/the_project.html

You may reach above link to see all the photographs

under fig. with photographs information and notes under numbers related to

essay for your research. You would like to research exhibition web page to read

and find out more essay and photographs to click above link.

1- THE MODERN

WORLD

Even before

the introduction of the handheld Leica camera in 1925, photographers were

avidly exploring fresh perspectives, shaped by the unique experience of

capturing the world through a lens and ideally suited to express the tenor of

modern life in the wake of World War I. Looking up and down, these photographers

found unfamiliar points of view that suggested a new, dynamic visual language

freed from convention. Improvements in the light sensitivity of photographic

films and papers meant that photographers could capture motion as never before.

At the same time, technological advances in printing resulted in an

explosion of opportunities for photographers to present their work to

ever-widening audiences. From inexpensive weekly magazines to extravagantly

produced journals, periodicals exploited the potential of photographs and

imaginative layouts, not text, to tell stories. Among the photographers on view

in this section are Martin Munkácsi (American, born Hungary, 1896–1963), Leni

Riefenstahl (German, 1902–2003), Aleksandr Rodchenko (Russian, 1891–1956), and

Willi Ruge (German, 1882–1961).

WILLI RUGE ( GERMAN 1882–1961 )

WITH MY HEAD

HANGING DOWN BEFORE THE PARACHUTE OPENED… 1931

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions Image: 14

× 20.3 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

ALEKSANDR RODCHENKO ( RUSSIAN 1891–1956 )

DIVE 1934

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions Image: 29.7

x 23.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by Exchange

WILLI RUGE ( GERMAN 1882 - 1961 )

SECONDS BEFORE LANDING SECONDS BEFORE LANDING

From the Series – I Photograph Myself during a Parachute

Jump 1931

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions Image: 20.4

× 14.1 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

LENI RIEFENSTAHL ( GERMAN 1902–2003 )

UNTITLED 1936

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions Image: 23.4

x 29.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection funds, by Exchange

WANDA WULZ (

ITALIAN 1903 - 1984 )

EXERCISE 1932

Gelatin Silver Print - Print Date 1932- 1939

Dimensions Image: 29.2 × 21.9 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection Funds, by Exchange

© Fratelli Alinari Museum Collections-Studio Wulz Archive,

Florence

ROBERT PETSCHOW (

GERMAN 1888 – 1945 )

LINES OF MODERN INDUSTRY: COOLING TOWER 1920 - 1929

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1920 - 1932

Dimensions Image: 8.5 × 11.5 cm - Sheet: 8.8 × 11.9 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Gift of Albert Renger-Patzsch, by Exchange

2- PURISM

The question

of whether photography ought to be considered a fine art was hotly contested

from its invention in 1839 into the 20th century. Beginning in the 1890s, in an

attempt to distinguish their efforts from hoards of Kodak-wielding amateurs and

masses of professionals, “artistic” photographers referred to themselves as

Pictorialists. They embraced soft focus and painstakingly wrought prints so as

to emulate contemporary prints and drawings, and chose subjects that

underscored the ethereal effects of their methods. Before long, however, most

avant-garde photographers had come to celebrate precise and distinctly

photographic qualities as virtues. On both sides of the Atlantic, photographers

were making this transition from Pictorialism to modernism, while occasionally

blurring the distinction. Exhibition prints could be made with precious

platinum or palladium, or matte surfaces that mimicked those materials. Perhaps

nowhere is this variety more clearly evidenced than in the work of Edward

Weston, whose suite of prints in this section suggests the range of appearances

achievable with unadulterated contact prints from his large-format negatives.

Other photographers on view include Karl Blossfeldt (German, 1865 - 1932),

Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902–2002), Jaromír Funke (Czech, 1896 - 1945),

Bernard Shea Horne (American, 1867 - 1933), and Alfred Stieglitz (American,

1864 - 1946).

JAROSLAV ROSSLER (

CZECH 1902 – 1990 )

UNTITLED 1923

- 1925

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1923 - 1935

Dimensions Image: 22.1 × 21.8 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Horace W.

Goldsmith Fund

Through Robert B. Menschel

© 2014 Sylva Vitove-Rösslerova

BERNARD SHEA HORNE (

AMERICAN 1867 – 1933 )

UNTITLED 1916

- 1917

Platinum Print

Print Date 1916 - 1917

Dimensions Image: 20.3 × 15.5 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

EDWARD WESTON ( AMERICAN 1886 – 1958 )

ATTIC 1921

Palladium Print

Dimensions: 18.9

× 23.9 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Grace M. Mayer Fund and gift of Mrs. Mary Donant and Carl

Sandburg, by Exchange

BERNARD SHEA HORNE (

AMERICAN 1867 – 1933 )

UNTITLED 1916

- 1917

Platinum Print

Print Date 1916 - 1917

Dimensions Image: 20.5 × 15.5 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

Grace M. Mayer Fund and gift of Mrs. Mary Donant and Carl

Sandburg, by Exchange

JAROMÍR FUNKE ( CZECH 1896–1945 )

PLATES 1923 -

1924

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions Image: 21.5

× 29.3 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by Exchange

EDWARD WESTON (

AMERICAN 1886 – 1958 )

STEEL: ARMCO, MIDDLETOWN, OHIO - 1922

Palladium Print - Print Date 1922

Dimensions Image: 23 × 17.4 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© 1981 Center for Creative Photography,

Arizona Board of Regents.

EDWARD WESTON ( AMERICAN 1886 – 1958 )

STEEL: ARMCO, MIDDLETOWN, OHIO - 1922

DESCRIPTION

In Edward

Weston’s journals, which he began on his trip to Ohio and New York in fall

1922, the artist wrote of the exhilaration he felt while photographing the

“great plant and giant stacks of the American Rolling Mill Company” in

Middletown, Ohio. He then went to see the great photographer and

tastemaker Alfred Stieglitz. Were he still publishing the magazine Camera Work, Stieglitz told him, he would have

reproduced some of Weston’s recent images in it, including, in particular, one

of his smokestacks. The photograph’s clarity and the photographer’s frank awe

at the beauty of the brute industrial subject seemed clear signs of advanced

modernist tendencies.

In moving

away from the soft focus and geometric stylization of his recent images, such

as Attic of

1921 (MoMA 1902.2001), Weston was discovering a more straightforward approach,

one of considered confrontation with the facts of the larger world much like

that of his close friend Johan Hagemeyer, who was photographing such modern

subjects as smokestacks, telephone wires, and advertisements. Shortly before

his trip east, Weston had met R. M. Schindler, the Austrian architect, and had

been excited by his unapologetically spare, modern house and its implications

for art and design. Weston was also reading avant-garde European art magazines

full of images and essays extolling machines and construction. Stimulated by

these currents, Weston saw that by the time he got to Ohio he was “ripe to

change, was changing, yes changed.”

The visit to

Armco was the critical pivot, the hinge between Weston’s Pictorialist past and

his modernist future. It marked a clear leave-taking from his bohemian circle

in Los Angeles and the first step toward the cosmopolitan connections he made

in New York and in Mexico City, where he moved a few months later to live with

the Italian actress and artist Tina Modotti. The Armco photographs went with

him and became talismans of the sea change, emblematic works that decorated his

studio in Mexico, along with a Japanese print and a print by Picasso. When he

sent a representation of his best work to the Film und Foto exhibition in Stuttgart in 1929,

one of the smokestacks was included.

In the midst

of such transformation, Weston maintained tried-and-true darkroom procedures.

He had used an enlarger in earlier years but had abandoned the technique

because he felt that too much information was lost in the projection. Instead

he increasingly favored contact printing. To make the smokestack print, Weston

enlarged his 3 ¼ by 4 ¼ inch (8.3 by 10.8 centimeter) original negative onto an

8 by 10 inch (20.3 by 25.4 centimeter) interpositive transparency, which he

contact printed to a second sheet of film in the usual way, creating the final

8 by 10 inch negative. Weston was frugal; he was known to economize by

purchasing platinum and palladium paper by the roll from Willis and Clements in

England and trimming it to size. He exposed a sheet of palladium paper to the

sun through the negative and, after processing the print, finished it by

applying aqueous retouching media to any flaws. The fragile balance of the

photograph’s chemistry, however, is evinced in a bubble-shaped area of cooler

tonality hovering over the central stacks. The print was in Modotti’s

possession at the time of her death in Mexico City, in 1942.

—Lee Ann

Daffner, Maria Morris Hambourg

JAROSLAV RÖSSLER ( CZECH 1902–1990 )

UNTITLED 1924

Pigment Print

Dimensions Image: 23

× 23 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Horace W. Goldsmith Fund Through Robert B. Menschel

3- REINVENTING

PHOTOGRAPHY

In 1925,

László Moholy-Nagy articulated an idea that became central to the New Vision

movement: although photography had been invented 100 years earlier, it was only

now being discovered by

the avant-garde circles for all its aesthetic possibilities. As products of

technological culture, with short histories and no connection to the old

fine-art disciplines—which many contemporary artists considered

discredited—photography and cinema were seen as truly modern instruments that

offered the greatest potential for transforming visual habits. From the

photogram to solarization, from negative prints to double exposures, the New

Vision photographers explored the medium in countless ways, rediscovering

known techniques and inventing new ones. Echoing the cinematic experiments of

the same period, this emerging photographic vocabulary was rapidly adopted by

the advertising industry, which appreciated the visual efficiency of its bold

simplicity. Florence Henri (Swiss, born America, 1893 - 1982), Edward Quigley

(American, 1898 - 1977), Franz Roh (German, 1890 - 1965), Franciszka Themerson

and Stefan Themerson (British, born Poland, 1907 - 1988 and 1910 - 1988), and

František Vobecký (Czech, 1902 - 1991) are among the numerous photographers

represented here.

EDMUND KESTING (

GERMAN 1892 – 1970 )

PHOTOGRAM LIGHTBULB 1927

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1927 - 1939

Dimensions Image: 29.6 × 39.7 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection funds, by Exchange

© 2014/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst,

Germany

EL LISSITZKY ( RUSSIAN 1890 – 1941 )

KURT SCHWITTERS 1924

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 10.8

× 9.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by Exchange

ISTVAN KERNY (

HUNGARIAN 1879 – 1963 )

NEPTUNE 1916

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1916–35

Dimensions Image: 16 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Robert

Capa, by Exchange

FRANCIS BRUGUIERE (

AMERICAN 1879 – 1945 )

VIOLENT INTERVENTION 1925

- 1929

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1925 - 1929

Dimensions Image: 24 x 18.9 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection Funds, by Exchange

© 1991 Kenneth H. Bruguière and Kathleen Bruguière Anderson

ALVIN LANGDON COBURN ( AMERICAN 1882 – 1966 )

VORTOGRAPH 1916 - 1917

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 28.2

x 21.2 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Grace M. Mayer Fund

ADOLF NAVARA (

CZECH, ACTIVE C. 1930S)

UNTITLED C.

1930

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date c. 1930–35

Dimensions Image: 29.5 x 22.8 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection Funds, by Exchange

HANS RICHTER ( AMERICAN, BORN GERMANY 1888 – 1976 )

UNTITLED STILL FROM FILM STUDY ( 1928 ) 1927

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 7.3

x 9.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

UNTITLED - FEBRUARY

1931

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1931–39

Dimensions Image: 33.5 x 23.4 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of James N.

Rosenberg, by Exchange

© 2014 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White/Licensed by

VAGA, New York

HANNES MEYER (

SWISS 1889 – 1954 )

FILM 1926

Two Gelatin Silver Prints Mounted on White Cardboard

Print Date 1926

Dimensions Image: 21.2 × 3.4 cm - Mount: 29.6 × 21 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

OSKAR NERLINGER ( GERMAN 1893 – 1969 )

MOTORCYCLE IN THE RACE 1925

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 22

× 17.4 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection Funds, by Exchange

STEFAN THEMERSON (

BRITISH, BORN POLAND 1910 – 1988 )

FRANCISZKA THEMERSON (

BRITISH, BORN POLAND 1907 – 1988 )

UNTITLED, FROM MOMENT MUSICAL 1933

Gelatin Silver Prints on White Cardboard

Print Date 1933 - 1935

Dimensions Mount: 37.8 × 39 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Abbott-Levy

Collection funds, by exchange

© 2014 Themerson Estate

FRANZ ROH (

GERMAN 1890 – 1965 )

UNTITLED 1928

- 1933

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1928 - 1935

Dimensions Image: 10.1 × 23.3 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© Estate Franz Roh, Munich

MODERN

PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE THOMAS WALTHER COLLECTION 1909 - 1949

THE COLLECTION

In the 1920s

and ’30s photography underwent a period of exploration, experimentation,

technical innovation, and graphic discovery so dramatic that it generated

repeated claims that the true age of discovery was not when photography was

invented but when it came of age, in this era, as a dynamic, infinitely

flexible, and easily transmissible medium. The Thomas Walther Collection

concentrates on that second moment of growth. The Walther Collection’s 341

photographs by almost 150 artists, most of them European, together convey a

period of collective innovation that is now celebrated as one of the major

episodes of modern art.

THE PROJECT

Our research

is based on the premise that photographs of this period were not born as

disembodied images; they are physical things—discrete objects made by certain

individuals at particular moments using specific techniques and materials.

Shaped by its origin and creation, the photographic print harbors clues to its

maker and making, to the causes it may have served, and to the treatment it has

received, and these bits of information, gathered through close examination of

the print, offer fresh perspectives on the history of the era.

“Object:Photo”—the title of this study—reflects this approach.

In 2010, the

Andrew W. Mellon Foundation gave the Museum a grant to encourage deep scholarly

study of the Walther Collection and to support publication of the results. Led

by the Museum’s Departments of Photography and Conservation, the project

elicited productive collaborations among scholars, curators, conservators, and

scientists, who investigated all of the factors involved in the making,

appearance, condition, and history of each of the 341 photographs in the

collection. The broadening of narrow specializations and the

cross-fertilization between fields heightened appreciation of the singularity

of each object and of its position within the history of its moment. Creating

new standards for the consideration of photographs as original objects and of

photography as an art form of unusually rich historical dimensions, the project

affords both experts and those less familiar with its history new avenues for

the appreciation of the medium. The results of the project are presented in

multiple parts: on the website, in a hard-bound paper catalogue of the entire

Thomas Walther Collection (also titled Object:Photo),

and through an interdisciplinary symposium focusing on the ways in which the

digital age is changing our engagement with historic photographs.

http://www.moma.org/interactives/objectphoto/the_project.html#intro

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK

Founded in 1929 as an educational institution, The Museum of

Modern Art is dedicated to being the foremost museum of modern art in the world.

Through the leadership of its Trustees and staff, The Museum

of Modern Art manifests this commitment by establishing, preserving, and

documenting a collection of the highest order that reflects the vitality,

complexity and unfolding patterns of modern and contemporary art; by presenting

exhibitions and educational programs of unparalleled significance; by

sustaining a library, archives, and conservation laboratory that are recognized

as international centers of research; and by supporting scholarship and

publications of preeminent intellectual merit.

Central to The Museum of Modern Art’s mission is the

encouragement of an ever-deeper understanding and enjoyment of modern and

contemporary art by the diverse local, national, and international audiences

that it serves. You may read more about MoMA’s entire information to click

below link.

http://press.moma.org/about/

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK

DIRECTOR DR. GLENN D. LOWRY

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK

DIRECTOR DR. GLENN D. LOWRY

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK

MODERN

PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE THOMAS WALTHER COLLECTION 1909 - 1949

HISTORICAL

CONTEXT

The Walther

Collection is particularly suited to such a study because its photographs are

so various in technique, geography, genre, and materials as to make it a mine

of diverse data. The revolutions in technology that made the photography of

this period so flexible and responsive to the impulse of the operator threw

open the field to all comers. The introduction of the handheld Leica

in 1925 (a small camera using strips of 35mm motion-picture

film), of enlargers to make positive prints from the Leica’s little negatives,

and of easy-to-use photographic papers—each of these was respectively a

watershed event. Immediately sensing the potential of these tools, artists

began to explore the medium; without any specialized training, painters such as

László Moholy-Nagy and Aleksandr Rodchenko could become photographers and

teachers almost overnight. Excitedly and with an open sense of possibility,

they freely experimented in the darkroom and in the studio, producing negative

prints, collages and photomontages, photograms, solarizations, and combinations

of these. Legions of serious amateurs also began to photograph, and

manufacturers produced more types of cameras with different dimensions and

capacities: besides the Leica, there was the Ermanox, which could function in

low light, motion-picture cameras that could follow and stop action, and many

varieties of medium- and larger-format cameras that could be adapted for easy

transport. The industry responded to the expanding range of users and equipment

with a bonanza of photographic papers in an assortment of textures, colors, and

sizes. Multiple purposes also generated many kinds of prints: best for

reproduction in books or newspapers were slick, ferrotyped glossies, unmounted

and small enough to mail, while photographs for exhibition were generally

larger and mounted to stiff boards. Made by practitioners ranging from amateurs

to professional portraitists, journalists, illustrators, designers, critics,

and artists of all stripes, the pictures in the Walther Collection are a true

representation of the kaleidoscopic multiplicity of photography in this period

of diversification.

CONSERVATION

SCIENCE

The

conservation objectives were manifold: to determine the manner of the

photographs’ construction—the material constituents of both the image and its

paper— and to test a new methodology, previously applied only to smaller sets

of pictures. To this end the conservation team gathered literature, magazines,

advertisements, and broadsides of the period—tracking the appearance and

history of once familiar products and techniques, so many now given up to

history—and launched into a suite of technical analyses for each photograph in

the collection. Chris McGlinchey, the Museum’s Sally and Michael Gordon

Conservation Scientist, who had pioneered the use of handheld X-ray

fluorescence (XRF) devices on photographs in 2001, set to work, and Ana

Martins, Associate Conservation Scientist, statistically evaluated the immense

data sets that the research had produced. Surface texture, a special line of

investigation for Paul Messier, independent conservator, and Jim Coddington,

the Museum’s Chief Conservator, drew on a body of research in imaging systems

built up by, among others, the Cultural Heritage Imaging group in San

Francisco, using techniques of polynomial mapping and reflectance

transformation imaging. Messier’s modifications of these methods enabled the

study, documentation, and sharing of the surfaces of photographs by the same

artists in other museum collections. The success of documenting photographs

from different collections with these kinds of reproducible results not only

raised the bar for standards of collaboration but made possible future

comparisons that adhere to these published methods and procedures. MoMA was

thus positioned not only to synthesize and mine the largest body of raw data on

a group of photographs ever gathered, but to extend that effort beyond its own

walls.

http://www.moma.org/interactives/objectphoto/the_project.html#intro

You may visit

a comprehensive web page that prepare for the exhibition of Modern Photographs

From the Thomas Walther Collection at Moma to read all the essays, artist’s

information and to see all the photographs with there knowledge to click below

special link.

http://www.moma.org/interactives/objectphoto/#home

THE ARTIST’S

LIFE

Photography

is particularly well suited to capturing the distinctive nuances of the human

face, and photographers delighted in and pushed the boundaries of portraiture

throughout the 20th century. The Thomas Walther Collection features a great

number of portraits of artists and self-portraits as varied as the individuals

portrayed. Additionally, the collection conveys a free-spirited sense of

community and daily life, highlighted here with photographs made by André

Kertész and by students and faculty at the Bauhaus. When the

Hungarian-born Kertész moved to Paris in 1925, he couldn’t afford to purchase

photographic paper, so he would print on less expensive postcard stock. These

prints, whose small scale requires that the viewer engage with them intimately,

function as miniature windows into the lives of Kertész’s bohemian circle of

friends. The group of photographs made at the Bauhaus in the mid-1920s, before

the medium was formally integrated into the school’s curriculum, similarly

expresses friendships and everyday life captured and printed

in an informal manner. Portraits by Claude Cahun (French,

1894 - 1954), Lotte Jacobi (American, born Germany, 1896 - 1990), Lucia Moholy

(British, born Czechoslovakia, 1894 - 1989), Man Ray (American, 1890 - 1976),

August Sander (German, 1876 - 1964) and Edward Steichen (American, born

Luxembourg, 1879 - 1973) are among the highlights of this gallery.

ANDRE KERTESZ ( AMERICAN, BORN HUNGARY 1894 –

1985 )

MONDRIAN'S GLASSES AND PIPE 1926

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1926–c. 1928

Dimensions Image: 7.9 × 9.3 cm - Sheet: 8.5 × 13.6 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer

Fund

© Estate of André Kertész

GEORG MUCHE (

GERMAN 1895 – 1987 )

REFLECTION: THE WEAVING WORKSHOP IN THE BALL 1921

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1921–25

Dimensions Image: 15.9 × 11.9 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

EL LISSITZKY (

RUSSIAN 1890 – 1941 )

SELF-PORTRAIT - 1924

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1924

Dimensions Image: 13.9 × 8.9 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Shirley

C. Burden, by exchange

© 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn

GERMAINE KRULL ( DUTCH, BORN GERMANY 1897 – 1985 )

JEAN COCTEAU 1929

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 22.3

× 16.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

GUSTAV KLUTSIS ( LATVIAN 1895 – 1938 )

UNTITLED 1926

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 8.9

× 6.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection Funds, by Exchange

IWAO YAMAWAKI ( JAPANESE 1898 – 1987 )

UNTITLED 1931

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 22

x 16.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection Funds, by Exchange

WALTER A. PETERHANS (

AMERICAN, BORN GERMANY 1897 – 1960 )

ANDOR WEININGER, BERLIN 1930

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1955–86

Dimensions Image: 21.7 × 15.6 cm - Sheet: 22.5 × 16.4 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© Estate Walter Peterhans, Museum Folkwang, Essen

GERTRUD ARNDT ( GERMAN 1903 – 2000 )

AT THE MASTERS’ HOUSES 1929 - 1930

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 22.6

x 15.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

LORE FEININGER ( GERMAN 1901 – 1991 )

ERICH SALOMON 1929

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 23.2

x 16.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

ANDRE KERTESZ ( AMERICAN, BORN HUNGARY 1894 –

1985 )

LÉGER STUDIO - 1927

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1927 - 1929

Dimensions Image: 10.3 × 7.9 cm - Sheet: 10.5 × 8.1 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© Estate of André Kertész

ANDRE KERTESZ ( AMERICAN, BORN HUNGARY 1894 –

1985 )

GÉZA BLATTNER 1925

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1925–35

Dimensions Image: 7.7 × 8.2 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© Estate of André Kertész

5- BETWEEN

SURREALISM & MAGIC REALISM

In the

mid-1920s, European artistic movements ranging from Surrealism to New

Objectivity moved away from a realist approach by highlighting the strange in

the familiar or trying to reconcile dreams and reality. Echoes of these

concerns, centered on the human figure, can be found in this gallery. Some

photographers used anti-naturalistic methods—capturing hyperreal, close-up

details; playing with scale; and rendering the body as landscape—to challenge

the viewer’s perception. Others, in line with Sigmund Freud’s definition of

“the uncanny” as an effect that results from the blurring of distinctions between

the real and the fantastic, offered visual plays on life and the lifeless,

the animate and the inanimate, confronting the human body with surrogates in

the form of dolls, mannequins, and masks. Photographers influenced by

Surrealism, such as Maurice Tabard, subjected the human figure to distortions

and transformations by experimenting with photographic techniques either while

capturing the image or while developing it in the darkroom. Additional

photographers on view include Aenne Biermann (German, 1898 - 1933),

Jacques-André Boiffard (French, 1902 - 1961), Max Burchartz (German, 1887 -

1961), Helmar Lerski (Swiss, 1871 - 1956), and Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz

(Polish, 1885 - 1939).

ANDRE KERTESZ ( AMERICAN, BORN HUNGARY 1894 –

1985 )

DISTORTION #126 - 1933

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1933 - 1939

Dimensions Image: 20.3 × 34 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© Estate of André Kertész

HERBERT BAYER ( AMERICAN, BORN AUSTRIA 1900 - 1985)

HUMANLY IMPOSSIBLE 1932

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 38.9

× 29.3 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Acquired Through the Generosity of Howard Stein

MAX BURCHARTZ ( GERMAN 1887 – 1961 )

EYE 1928

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 30.2

x 40 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Acquired Through the Generosity of Peter Norton

MAURICE TABARD ( FRENCH 1897 – 1984 )

SOLARIZED FILM 1936

Gelatin Silver Print - Print Date 1936 - 1955

Dimensions Image: 24.1 x 12 cm - Mount: 24 × 18 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Gift of Robert Shapazian, by Exchange

MAURICE TABARD ( FRENCH 1897 – 1984 )

UNTITLED 1928

( HAND ON WALL WITH SHADOW )

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 17.7

x 22.9 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

RAOUL HAUSMANN

UNTITLED - FEBRUARY

1931

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1931-1933

Dimensions Image: 13.7 × 11.3 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© 2014 Raoul Hausmann/Artists Rights Society (ARS),

New York/ADAGP, Paris

RAOUL HAUSMANN

UNTITLED - FEBRUARY 1931

DESCRIPTION

As a key

member of the Berlin-based Dadaists, between 1918 and 1922 Raoul Hausmann

exhibited assemblage sculptures, collages, and photomontages made with

magazines and newspaper clippings. Being a Dadaist, he dissociated himself from

photography— considered a positivist medium—in a 1921 unpublished manifesto

titled “Wir sind nicht die Photographen” (We are not the photographers), but by

the late twenties he had taken up photography in earnest, making

straightforward images of landscapes and plants before turning to more

experimental works on light and optics.

Hausmann made

this untitled image in February 1931, during his intensive years of

experimental photography and prior to his departure from Berlin in 1933. The

model is his second wife, Hedwig Mankiewitz-Hausmann, who is pictured in other

of his photographs from early that year. This print is among Hausmann’s more

modest small formats from the early 1930s. He enlarged the image onto double

weight paper with a semireflective surface and later trimmed the print;

Hausmann printed on a range of paper types but favored German Agfa-Brovira

papers. On the verso, the presence of adhesive residues along the top and

a faint dark spot at the top center, possibly due to adhesive

residue, indicates that this print was previously attached to a support,

perhaps as part of a photomontage or other presentation.

Hausmann took

at least two other images of this model and mirror, most likely at the same

time. He used one in an untitled photomontage exhibited

in Fotomontage,a show organized by his friend César

Domela-Nieuwenhuis and mounted in April–May 1931 at the Staatliche

Kunstbibliothek in Berlin. Hausmann published this image in the Cologne-based

review A bis Z, in May 1931. In 1946 he included another version in

two other photomontages: L’Acteur (now in the collection

of Institut Valencià d’Art Modern) and an untitled work

in which he kept only a part of the enlarged eye. In all the images, the

reflection in the shaving mirror magnifies the organ of vision, the eye, in

line with many avant-garde photographic works of that period. The round mirror

becomes a metaphor for the camera’s mechanical lens, which enables the operator

to see the world literally larger than life. In another untitled work (MoMA

1689.2001), Hausmann used a lens instead of a mirror to achieve a similar

magnification.

—Quentin

Bajac, Hanako Murata

JOHAN NIEGEMAN (DUTCH 1902 – 1977 )

UNTITLED 1926

- 1929

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 7.5

× 10.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

UMBO ( OTTO UMBEHR ) (

GERMAN 1902 – 1980 )

WARRIORLIKE FACE 1926

- 1927

Gelatin Silver Print - Print Date 1926–27

Dimensions Image: 17.3 × 12.2 cm - Sheet: 17.7 × 12.9 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© 2014 Umbo/Gallery Kicken Berlin/Phyllis Umbehr/VG

Bild-Kunst, Bonn

HARRY LACHMAN ( AMERICAN 1886 – 1975 )

UNTITLED STILL FROM THE MAGICIAN ( 1926 ) 1925

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 22.7

x 28.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

6- DYNAMICS

OF THE CITY

In his 1928

manifesto “The Paths of Contemporary Photography,” Aleksandr Rodchenko

advocated for a new photographic vocabulary that would be more in step with the

pace of modern urban life and the changes in perception it implied. Rodchenko

was not alone in this quest: most of the avant-garde photographers of the 1920s

and 1930s were city dwellers, striving to translate the novel and shocking

experience of everyday life into photographic images. Equipped with newly

invented handheld cameras, they used unusual vantage points and took photos as

they moved, struggling to re-create the constant flux of images that

confronted the pedestrian. Reflections in windows and vitrines, blurry images

of quick motions, double exposures, and fragmentary views portray the visual

cacophony of the metropolis. The work of Berenice Abbott (American, 1898

- 1991), Alvin Langdon Coburn (American, 1882 - 1966), Germanie Krull

(Dutch, born Germany, 1897 - 1985), Alexander Hackenschmied (Czech, 1907 -

2004), Umbo (German, 1902 - 1980), and

Imre Kinszki

(Hungarian, 1901 - 1945) is featured in this final gallery.

http://www.moma.org/visit/calendar/exhibitions/1496

ANDRE KERTESZ ( AMERICAN, BORN HUNGARY 1894 –

1985 )

GRANDS BOULEVARDS 1926

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1926 - 1935

Dimensions Image: 7.8 x 10.9 cm - Sheet: 8.4 × 12.9 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© Estate of André Kertész

ANTON BRUEHL (

AMERICAN, BORN AUSTRALIA 1900 – 1982 )

UNTITLED 1929

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1929–55

Dimensions Image: 25.3 × 20.2 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© 2014 Anton Bruehl Estate

CHARLES SHEELER( AMERICAN 1883 – 1965 )

FORD PLANT, RIVER ROUGE, BLAST FURNACE AND DUST CATCHER 1927

Gelatin Silver Print - Print

Date 1927 - 1944

Dimensions Image: 24.1 × 19.2 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Horace W.

Goldsmith Fund through Robert B. Menschel and gift of Lincoln Kirstein, by

Exchange

© 2014 The Lane Collection

CESAR DOMELA –

NIEUWENHUIS ( DUTCH 1900 – 1992 )

HAMBURG, GERMANY'S GATEWAY TO THE WORLD 1930

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1930–32

Dimensions Image: 40.3 × 41.9 cm - Mount: 48.5 × 49.9 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection funds, by exchange

© 2014 César Domela/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

/ ADAGP, Paris.

WALKER EVANS ( AMERICAN 1903 – 1975 )

VOTIVE CANDLES, NEW YORK CITY 1929 - 1930

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 21.6

x 17.7 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection. Gift of Willard Van Dyke and Mr. and Mrs. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., by

Exchange

FLORENCE HENRI ( SWISS, BORN AMERICA 1893 – 1982 )

UNTITLED 1928 - 1930

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 9.1

× 12 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Eulabee Dix, by Exchange

J. JAY HIRZ ( AMERICAN )

BROOKLYN BRIDGE IN RAINY WEATHER 1927

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 24.2

× 19.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

LEE MILLER ( AMERICAN 1907 – 1977 )

UNTITLED 1929

- 1932

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1929–39

Dimensions Image: 21.3 × 24.8 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. The Family of

Man Fund

© 2014 Lee Miller Archives, England

MARJORIE CONTENT (

AMERICAN 1895 – 1984 )

STEAMSHIP PIPES, PARIS

Winter 1931

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1931–65

Dimensions Image: 9.7 × 6.8 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Andreas

Feininger, by exchange

© Estate of Marjorie Content

JAROSLAV ROSSLER (

CZECH 1902 – 1990 )

UNTITLED 1924

Gelatin Silver Print With Pencil and Black Ink

Dimensions Image: 24.1

x 22.8 cm

Medium Gelatin Silver Print With Pencil and Black Ink

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Robert B.

Menschel Fund, by exchange

© 2014 Sylva Vitove-Rösslerova

UMBO ( OTTO UMBEHR ) (

GERMAN 1902 – 1980 )

MYSTERY OF THE STREET 1928

Gelatin Silver Print - Print Date 1928- 1932

Dimensions Image: 29 x 23.5 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by Exchange

© 2014 Sylva Vitove-Rösslerova

UMBO ( OTTO UMBEHR ) ( GERMAN 1902 – 1980 )

MYSTERY OF THE STREET 1928

DESCRIPTION

Trained at

the Bauhaus under Johannes Itten, a master of expressivity, Berlin-based

photographer Umbo (born Otto Umbehr) believed that intuition was the source of

creativity. To this belief, he added Constructivist structural strategies

absorbed from Theo Van Doesburg, El Lissitzky, and others in Berlin in the

early twenties. Their influence is evident in this picture’s diagonal, abstract

construction and its spatial disorientation. It is also classic Umbo,

encapsulating his intuitive vision of the world as a resource of poetic, often

funny, ironic, or dark bulletins from the social unconscious.

After he left

the Bauhaus, Umbo worked as assistant to Walther Ruttmann on his film Berlin, Symphony of a Great

City 1926. In 1928, photographing from his window

either very early or very late in the day and either waiting for his “actors”

to achieve a balanced composition or, perhaps, positioning them as a movie

director would, Umbo exposed three negatives. He had an old 5 by 7 inch (12.7

by 17.8 centimeter) stand camera and a 9 by 12 centimeter (3 9/16 by 4 ¾ inch)

Deckrullo Contessa-Nettle camera, but which he used for these overhead views is

not known, as he lost all his prints and most negatives in the 1943 bombing of

Berlin. The resulting images present a world in which the shadows take the

active role. Umbo made the insubstantial rule the corporeal and the dark

dominate the light through a simple but inspired inversion: he mounted the

pictures upside down (note the signature in ink in the lower right).

In 1928–29,

Umbo was a founding photographer at Dephot (Deutscher Photodienst), a seminal

photography agency in Berlin dedicated to creating socially relevant and

visually fascinating photoessays, an idea originated by Erich Solomon. Simon

Guttmann, who directed the business, hired creative nonconformists, foremost

among them the bohemian Umbo, who slept in the darkroom; Umbo in turn drew the

brothers Lore Feininger and Lyonel Feininger to the agency, which soon also

boasted Robert Capa and Felix H. Man. Dephot hired Dott, the best printer in Berlin,

and it was he who made the large exhibition prints, such as this one, ordered

by New York gallerist Julien Levy when he visited the agency in 1931. Umbo showed thirty-nine works, perhaps also printed by

Dott, in the 1929 exhibition Film und Foto, and

he put Guttmann in touch with the Berlin organizer of the show; accordingly,

Dephot was the source for some images in the accompanying book, Es

kommt der neue Fotograf! (Here comes the new photographer!).

Levy introduced Umbo’s photographs to New York in Surréalisme (January

1932) and showcased them again at the Julien Levy Gallery, together with images

by Herbert Bayer, Jacques-André Boiffard, Roger Parry, and Maurice Tabard, in

his 1932 exhibition Modern European Photography.

—Maria Morris

Hambourg, Hanako Murata

RAOUL HAUSMANN (

GERMAN, BORN AUSTRIA 1886 – 1971 )

UNTITLED C.

1930

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1960 - 70

Dimensions Image: 18.2 × 22.6 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Horace W.

Goldsmith Fund through Robert B.

© 2014 Raoul Hausmann/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New

York/ADAGP, Paris

PAUL CITROEN ( DUTCH, BORN GERMANY 1896 – 1983 )

METROPOLIS 1923

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 20.3

× 15.3 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

© 2014 Paul Citroen/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New

York/Pictoright, Amsterdam

IMRE KINSZKI ( HUNGARIAN 1901 – 1945 )

UNTITLED C. 1930

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 8.5

x 11.6 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Thomas Walther

ALEKSANDR RODCHENKO ( RUSSIAN 1891 – 1956 )

DEMONSTRATION 1932

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 29.6

× 22.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Shirley C. Burden, by Exchange

FRED KORTH (AMERICAN, BORN GERMANY 1902 – 1983 )

UNTITLED C. 1928

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 5.5

× 7.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of Robert and Joyce Menschel, by Exchange

DZIGA VERTOV (

RUSSIAN, 1895 – 1954 )

UNTITLED 1927

- 1928

Gelatin Silver Print - Print Date 1927 - 1932

Dimensions Image: 13.4 × 8.9 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection Funds, by Exchange

LASZLO MOHOLY - NAGY (

AMERICAN, BORN HUNGARY. 1895 – 1946 )

BERLIN, RADIO TOWER 1928

Gelatin Silver Print

Print Date 1928–36

Dimensions Image: 38.1 × 27.8 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn

SASHA STONE (

AMERICAN, BORN RUSSIA 1895 – 1940 )

THE EINSTEIN TOWER IN POTSDAM (THE COELOSTAT IN THE UPPER

DOME

THAT CATCHES AND PROJECTS THE LIGHT OF THE STARS INTO THE LABORATORY) 1928

Gelatin Silver Print - Print

Date 1928 - 1935

Dimensions Image: 23.1 × 17.4 cm

Credit Line Thomas Walther Collection.

Abbott-Levy Collection Funds, by Exchange

GERMAINE KRULL ( DUTCH, BORN GERMANY 1897–1985)

UNTITLED 1926 - 1928

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 16.9

x 22.9 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Thomas Walther

Collection.

Gift of David H. McAlpin, by Exchange

FACE

TIME BY MATTHEW S. WITKOVSKY

LOOKING FOR WORK

Photography came into circulation

around 1840, in the grand age of the bourgeoisie, and before it could be

accepted as art, it had to be shown to be honorable work. According to literary

historian Franco Moretti, “The creation of a culture of work has been,

arguably, the greatest symbolic achievement of the bourgeoisie as a class.”1

In his compactly sweeping study The Bourgeois (2013), Moretti traces the

rise and fall of this class, which he asserts has lately disappeared from

discourse, though its standards and aspirations remain everywhere embedded in

popular consciousness. Near the start of his chronology Moretti places Daniel

Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719), whose protagonist, Moretti points out, puts in

far more hours tending to his abundantly wellprovisioned castaway’s

domain than the average English wage laborer did in the factory — even in

Defoe’s time of capitalism without fetters.2 Although the novel’s plot is

predicated on the total otherness of its solitary, uncivilized setting, Crusoe

demonstrates his continuing social value through over-compensation,

presumably to avoid the appearance that he is enjoying an endless island vacation.

Such a dilemma would confront photographers repeatedly across photography’s

first century, for their traffic in “instantaneously” completed likenesses

could seem unearned.3 The enduring Pictorialist movement, which began in

Victorian England in the 1880s and soon spread internationally among the middle

classes, explained the art value of photography largely in terms of expen

diture (of time and money), whether on complex printing processes or on

matting, calligraphic adornment, and other presentational devices. To be art,

it had to be serious effort: Camera Work, as Alfred Stieglitz called his

leading Pictorialist journal. The Pictorialists declared they were

striving for imagination, and in their love of soft focus and vague contours

they may have in fact unwittingly provided one of the more imaginative

analyses of their artistic inheritance: “many perspicuous details, adding up to

a hazy whole,” as Moretti terms the work of prose in Defoe’s great

novel.4 Pictorialism performed a cultural service by putting the haze on view.

Photographic modernism of the 1910s and ’20s overturned Pictorialist

compositional habits, to be sure, but its American contingent, in a sad cliché,

perpetuated the absolute insistence on effort as an index of artistic achievement.

The Europeans, by contrast, struck a remarkable balance between work and its

denial. At the Bauhaus, entire careers were made in photography taken during

“off hours,” such as group portraits of students perched on the dormitory

balcony or relaxing on the sand. These portraits emanate a lightness and

portability that applies as much to the personal relationships memorialized as

to the handheld cameras that memorialized them. Leisure scenes abound: the

repertory of Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy’s photographic subjects, for

example, stretches from dolls, children, and house pets to foreign towns,

activities like bathing and sailing, and viewing platforms at tourist sites

such as the Berlin Radio Tower (MoMA 1793.2001) and the

Rothenburg cathedral. Modernist photographic portraiture in Europe — at the

Bauhaus and elsewhere — brought playfulness into the art world at an

unprecedented scale. Whether capturing the mock seriousness of Claude Cahun and

Gertrud Arndt costumed as mash-ups of respectable citizens with outcasts — the

soldier meets the vamp for Cahun; the mademoiselle meets the madam for Arndt

(fig. 1) — or the outright laughter of Czech surrealist Václav Zykmund holding

a light bulb with his teeth (fig. 2), (self-) portrait photography in Europe in

the 1920s and ’30s became an expression of the irrepressible.

“Irrepressibility” stands opposite to the bourgeois keywords that Moretti so

brilliantly analyzes, including “utility,” “seriousness,” “comfort,” and

“precision.” The opposition is so perfect that one could argue for European

modernist photography as a mere safety valve in an otherwise thoroughly

repressive civilization. “Containing one’s immediate desires is not just

repression: it is culture,” Moretti observes, offering as example an analysis

of Crusoe’s contorted narration as he reluctantly kills a mother goat and

her kid to ease his hunger.5 Not denial, but containment. In an analogous

fashion, leisure and even sleep — another great occasion for Moholy-Nagy and

many others to make portraits (e.g., MoMA 1688.2001) — have long been

understood as necessary but limited escapes from the otherwise all encompassing

world of work.

In that sense, no amount of fooling around could

seriously challenge the work a day life of the bourgeoisie. Only photography as

redolent of labor as labor itself might perform this analysis — and not

by imitating high art, which was itself conventionally understood as a

refuge or escape. August Sander’s life project, People of the Twentieth Century

(Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts), gives such an analysis in exemplary

form. The very model of a bourgeois professional, Sander also turned his

thousands of sitters into citizens of an upstanding, thoroughly bourgeois

nation. Yet the signal feature of his great project was its necessary

incompleteness, a thoroughly sober form of irrepressibility. There could and

must always be more types of citizens to portray and add to the

infinitely expanding archive. This challenge to containment lay in the

very structure of Sander’s project. In addition, his encyclopedic undertaking

nuanced the terms by which the bourgeoisie typically made creativity into

labor, through close management and control. Products of an unstoppable

tradesman, Sander’s photographs hyperbolize the terms of Moretti’s analysis and

thus induce a reflection on those terms akin to Moretti’s own.

Sander gradually formulated his proposal to “map” the German character in portrait photographs, beginning at the start of the 1920s, some two decades into his career. The exceedingly ambitious plan to group all his existing and future portraits according to heteronomous portfolios of “types,” such as farmers, intellectuals, and women, depended on the outright incompatibility of its constituent subjects. This project would take shape as “a mosaic picture,” as the photographer later characterized it to fellow artist Peter Abelen.6 Sander pointedly displayed his photographs two per frame, and in

two rows, at the first public showing of his work-in-progress, in a Cologne group exhibition in 1927. Each portrait could be seen only alongside others. In the foreword to Sander’s 1929 book, Antlitz der Zeit (The face of our time), subtitled 60 Fotos deutscher Menschen (60 photos of German people), novelist Alfred Döblin pointed up the value of this approach, calling it “comparative photography.”7

One can

argue the other side, too: a mosaic is made of differently colored

pieces, but it does typically form a unified picture. Sander may be said to

have contained, not heightened, conflicting social truths in his portraiture by

assimilating his multicolored subjects to a graying bourgeois nation. To return

to Moretti’s keywords, one sees that it is work above all that unites the many

citizens portrayed by Sander, just as it is a bourgeois ideal of work that

defines Sander’s project, and arguably the general ethos of Neue Sachlichkeit

(New Objectivity), the movement to which his photographs are generally assigned

by art historians.

It is a constitutive fact of Sander’s photographs that

everyone, even intellectuals and the unemployed, has a job to do. Furthermore,

Sander shows service professions but no servants — each sitter appears in his

portraits as master of his or her occupation. Sander did not exempt himself

from these bourgeois values. Why should he? Photography was a respected part of

industrial labor and had been since the later nineteenth century. Portrait

photography was a trade, not a form of fine art, and Sander, like so many

others looking to be modern, explicitly distanced himself from colleagues who

strove for the qualities of fine art: “Nothing is more hateful to me than

sugarcoated photography with tricks, poses, and special effects.”8 Contempt for

Kunstphotographie was widely shared among progressive photographers as well as

avantgarde artists. What is surprising, in retrospect, is not that these

modernists disliked banalizing a potentially useful profession (photography)

with the trappings of fine art, but that, in Neue Sachlichkeit, not just photographers

but also so many modern artists — inheritors of a great tradition of

anti- bourgeois, anti-careerist bohemianism — depicted themselves

demonstratively as professionals. Painter Georg Scholz, in his selfportrait of

1926 “in front of an advertising column” (fig. 3), might be mistaken for a

banker, protectively overcoated as he fronts for a small universe of consumer

goods and advertisements that he could as well have financed or purchased as

painted. Scholz the creator carries no association with bohemians in this

canvas; he could even be an ad man or a product or graphic designer, a

maker of useful images, pictures that serve a purpose for capital.

Painting and photography of the Neue Sachlichkeit are aligned, beyond any

question of form or facture, in their shared assimilation to the bourgeoisie.

To this point, Sander’s chosen settings unprecedentedly conflate working and

living space. Although his subjects are identified by occupation, the spaces of

Sander’s portraiture emanate a comfort and intimacy typically associated with

the domestic interior, the single most vaunted bourgeois location. White-collar

professionals pose in their studies; painters sit

in chairs or stand in their studios; women of leisure

sway or relax in living rooms. Sander rarely photographed in a larger

work environment, such as a factory, a street, or an office building. Most

sitters are pictured against a warmly neutral background that suggests a

spatial refuge. Coming close for his exposure, and softening the focus around

their bodies, Sander made all his subjects look at home. Even a setting clearly

associated with gatherings away from home, such as the restaurant kitchen in

which the famous pastry chef greets the photographer (as one professional

to another), appears as a home away from home (fig. 4). The chef fills this

workspace with his bulk and solidly takes possession of it. His surroundings

dissolve from focus, as in a painting by Vermeer, so that the workplace becomes

a space of comfort. Comfort — cum plus forte, or “with strength” — is a word

that once meant succor but came to mean well-being: a state finely balanced

between necessaries and luxuries. Moretti observes that comfort is a key term

of desire for that class of humanity that need not worry over basic survival

but does fret at ostentation. “Comfort is no longer what returns us to a

‘normal’ state from adverse circumstances,” he writes, “but what takes

normality as its starting point and pursues well-being as an end in

itself.”9

What in Sander’s photographic project could disturb that

well-being? Only its state of perpetual incompletion. Scholar Susanne Lange has

asserted that Sander was aware from the start that his project must remain

forever partial, or what one could call, following Marcel Duchamp,

“definitively unfinished.” She cites as evidence his earliest written

announcement of People of the Twentieth Century, made in a letter to

photography historian and collector Erich Stenger in 1925: “As soon as my work

is completed, if one can even speak of completion in this context, I am

thinking to publish the entire oeuvre in an exhibition tour through various

cities.”10 The quixotic nature of Sander’s oft-expressed hope of publishing the

full series is of a piece with the inherent infinitude of his chosen task. He

persevered after the Nazis destroyed the printing plates for Antlitz der Zeit;

and he continued to make some new photographs as well as to promote his older

ones even after losing twenty-five to thirty thousand glass negatives in a fire

that consumed the basement of his Cologne studio in January 1946.11 (This after

the photographer had spent years secreting his life’s work around the

Westerwald countryside, to avoid its destruction by Allied bombs.) Nothing

would stop him — nor could the project ever find an end.

Sander repeatedly expanded an original list of seven portfolio headings that he had typed up in the mid-1920s, adding categories that addressed, for example, National Socialism. A true encyclopedist, he also wished to update and extend those subjects that had formed his earliest interest, creating subgroupings like “Farmers in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century.”12 The point of origin is clear, while the end point cannot even be imagined. It is only fitting that Sander’s son, grandson, and great-grandson have all continued to tend to his life project.13 The creator of a colossal monument to work creates more work even from beyond the grave.

At the same time, there can be no new photographs by Sander himself; his descendants are handling a mosaic to which further tesserae will not be added. Its incompleteness remains, perversely, its greatest promise, that of society as a montage without end. “Description as a form was not neutral at all,” Moretti writes, referring to the advent of realism in nineteenth-century literature and art: “Its effect was to inscribe the present so deeply into the past that alternatives became simply unimaginable.”14 Not so when the picture was conceived as a necessarily incomplete inscription. In that case there must always be more to write.

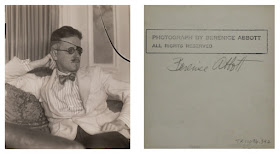

MACHINE

WORK

Sander was far from the only artistically ambitious

photographer attracted to portraiture in the 1920s and ’30s. To work in

photography and consider oneself an artist took a strong degree of

self-consciousness, which manifested itself most directly in portraits or

self-portraits in which the sitters are depicted alongside cameras. Such images

proliferated in the 1920s and ’30s; photographers, historically the

greatest advocates for their profession in print, now seemed delighted to

recommend it through pictures as well. Following in the lineage of mid-

nineteenth-century views of photographers standing surrounded by

assistants, chemistry vials, or other signs of mastery and knowledge, such

pictures would traditionally have been classed in the genre of the occupational

portrait. A self-portrait by Edward Steichen from around 1917 (fig. 5) is one

such modern example. Steichen, a protean character whose one life constant was

an unflagging hold on power, projects a confi- dence in his ability to connect

that was indispensable to a career spent taking portraits of the rich and

famous, from Auguste Rodin or J. P. Morgan to actresses such as Gertrude

Lawrence (MoMA 1869.2001). In his self-portrait (one of a few that he composed

just prior to joining the United States military as Commander of Aerial

Photography), the camera itself, shrouded in marginal shadow, is notably

insignificant compared to its artificially illumined operator.

It is the

machine that dominates its operator, by contrast, in many of the most

progressive portraits or selfportraits with cameras made in the early twentieth

century — again, principally in Europe. For one, the deference of the typical

occupational portrait toward its subject, which equates (as in the Steichen) to

a sense of distance, is replaced in these more progressive works by a

sense of proximity that can seem either intimate or claustrophobic. In

addition, the proud ego feci of artistic selfportraiture, which has a grand

lineage in painting traceable to Velázquez and Dürer, falters when the brush is

replaced by an imaging device that has its own, impersonal stare. As Paul

Citroen looked into a mirror to make his self-portrait in 1930, the camera on

its tripod looked with him (MoMA 1653.2001); and though he clearly pressed the