LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY’S RETROSPECTIVE: FUTURE PRESENT AT

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM NEW YORK

May 27, 2016 - September 7, 2016

LASZLO

MOHOLY-NAGY’S RETROSPECTIVE: FUTURE PRESENT AT

SOLOMON

R. GUGGENHEIM NEW YORK

May 27,

2016 - September 7, 2016

The

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum will present the first comprehensive retrospective

in the United States in nearly fifty years of the work of pioneering artist and

educator László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946). Organized by the Solomon R. Guggenheim

Foundation, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Los Angeles County Museum of

Art, Moholy-Nagy: Future Present examines the full career of the utopian

modernist who believed in the potential of art as a vehicle for social

transformation, working hand in hand with technology. Despite Moholy-Nagy’s

prominence and the visibility of his work during his lifetime, few exhibitions

have conveyed the experimental nature of his work, his enthusiasm for

industrial materials, and his radical innovations with movement and light. This

long overdue presentation, which encompasses his multidisciplinary methodology,

brings together more than 300 works drawn from public and private collections

across Europe and the United States, some of which have never before been shown

publicly in this country. After its debut presentation in New York, the

exhibition will travel to the Art Institute of Chicago (October 2, 2016–January

3, 2017) and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (February 12–June 18,

2017).

Moholy-Nagy:

Future Present is co-organized by Carol S. Eliel, Curator of Modern Art, Los

Angeles County Museum of Art; Karole P. B. Vail, Curator, Solomon R. Guggenheim

Museum; and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Richard and Ellen Sandor Chair and Curator,

Department of Photography, Art Institute of Chicago. The Guggenheim

presentation is organized by Vail, with the assistance of Ylinka Barotto,

Curatorial Assistant, and Danielle Toubrinet, Exhibition Assistant.

Moholy-Nagy:

Future Present provides an opportunity to examine the full career of this influential

Bauhaus teacher, founder of Chicago’s Institute of Design, and versatile artist

who paved the way for increasingly interdisciplinary and multimedia work and

practice. Among his radical innovations were his experiments with cameraless

photographs (which he dubbed “photograms”); use of industrial materials in

painting and sculpture that was unconventional for his time; researching with

light, transparency, and movement; his work at the forefront of abstraction;

and his ability to move fluidly between the fine and applied arts. The

exhibition is presented chronologically up the Guggenheim’s rotunda and

features collages, drawings, ephemera, films, paintings, photograms,

photographs, photomontages, and sculptures. The exception to the sequential

order is Room of the Present (Raum der Gegenwart) in the High Gallery, a

contemporary fabrication of a space originally conceived by Moholy-Nagy in 1930

but never realized in his lifetime. Constructed by designers Kai-Uwe Hemken and

Jakob Gebert, the largescale work contains photographic reproductions, films,

slides, documents, and replicas of architecture, theater, and industrial

design, including a 2006 replica of his kinetic Light Prop for an Electric

Stage (Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne, 1930). Room of the Present

illustrates the artist’s belief in the power of images and his approach to the

various means with which to view them- a highly relevant paradigm in today’s

constantly shifting and evolving technological world. Room of the Present will

be on display at all three exhibition venues and for the first time in the

United States. The Guggenheim installation is designed by Kelly Cullinan,

Senior Exhibition Designer, and is inspired by Moholy-Nagy’s texts on space and

his concept of a “spatial kaleidoscope” as applied to the experience of walking

up the ramps.

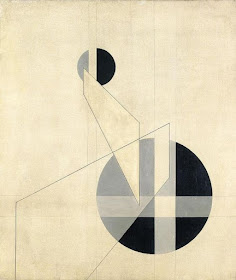

A 19, 1927

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 80 x 95.5 cm

Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, MI

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, MI

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York

“ For a

new ordering of a new world the need arose again to take possession of the

simplest elements of expression, color, form, matter, space. ”

László Moholy-Nagy, “On the Problem of New

Content and New Form” (1922)

Born

into a Jewish family in rural Hungary, Moholy-Nagy began to publish poetry and

short stories at a young age. In 1915, he left the University of

Budapest, where he had enrolled as a law student, to serve as an artillery

officer in the Austro-Hungarian army. While enlisted, he made numerous

drawings and sketches. After convalescing from a hand wound he suffered

on the Russian front, he continued to publish poems, stories, and reviews for

the Hungarian literary journal Jelenkor (Present age). After his discharge from

the army in 1918, he attended classes at a free art school in Budapest,

where he studied the works of old masters, particularly Rembrandt, as

well as those of Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and practitioners of

Cubism and Futurism. He frequented the city’s lively café scene and came into

close contact with Magyar Aktivizmus (Hungarian Activism), the influential

avant-garde artistic and antimilitary movement headed by the artist and

writer Lajos Kassák, who also founded the short-lived association MA

(Today) and the eponymous magazine.

In

autumn 1919, Moholy-Nagy moved to Vienna for a brief period before settling in

Berlin in early spring 1920, where he became the correspondent for MA. There he

met his future wife, Lucia Schulz, a socially and politically engaged

photographer and editor. He also met Dada artists—whose works had already

influenced his own—and encountered Constructivism, which had a formative impact

on his developing style and aesthetics

A 19, 1927 (DETAIL )

PHOTOGRAM, 1924 (PRINTED 1929)

Gelatin Silver Print (Enlargement From a Photogram)

Dimensions: 95.5 x 68.5 cm - Frame: 126.2 x 98.7 x 4

cm

Galerie Berinson, Berlin

PHOTOGRAM,

( MOONFACE ) ( SELF-PORTRAIT IN PROFILE ), 1926, PRINTED 1935

Collection

of Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, Michigan

CH B3, 1941 (PART FROM PAINTING)

CH B3, 1941

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 127 x 203 cm

Private Collection

PHOTOGRAM, 1941

Gelatin Silver Photogram

Gelatin Silver Photogram

Dimensions: 28 x 36 cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Sally Petrilli, 1985

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Sally Petrilli, 1985

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York

ADVERTISEMENT FOR LONDON UNDERGROUND, 1936

Color Lithograph

Dimensions: 101.5 x 62.9 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Philip

Johnson 1950

ADVERTISEMENT FOR LONDON UNDERGROUND, 1937

Color Lithograph

Dimensions: 101 x 63 cm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The London Underground underwent remarkable growth in the early 1930s, with the new stations and platforms adhering to a distinctive architectural style. Moholy-Nagy designed visually compelling posters for the city’s sophisticated transportation system that laud it as an example of scientific progress and modern proficiency.

ADVERTISEMENT FOR LONDON UNDERGROUND, 1937

Color Lithograph

Dimensions: 101.3 x 63.2 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Philip

Johnson 1950

“ New

creative experiments are an enduring necessity. ”

László Moholy-Nagy, “Production-Reproduction”

(1922)

Moholy-Nagy

began to move away from representational imagery as he became influenced

by the Constructivists, who believed art should reinforce social reform through

simple, minimal forms in order to reflect the modern industrial world. He began

to paint abstract geometric canvases in which diagonals, curves, circles,

half-moons, and bands of color form architectural structures in space. The

shapes seem to overlap, creating the illusion of a kind of glass architecture,

a nod to the value of transparency and light proclaimed by German writers and

modern architects in the early part of the twentieth century.

A

prolific writer, Moholy-Nagy began to collaborate with others on texts and

manifestos, including “Manifesto of Elemental Art” (1921), written with Hans Arp,

Raoul Hausmann, and Iwan Puni. He participated in his first exhibition at the

avant-garde gallery Der Sturm in Berlin in February 1922 with the Hungarian

artist László Péri. The presentation, which included abstract paintings as well

as assemblages and reliefs made of industrial materials, was successful,

earning him subsequent exhibitions and the

publication of his woodcut designs in the gallery’s periodical. This

recognition also spurred the publication of several important essays, including

“Production-Reproduction” (1922), in which the artist formulated his theories

for a new understanding of a person’s relationship to “creative activity” and

documented novel recording methods with respect to the phonograph, photography,

and film. In “Dynamic-Constructive Systems of Forces” (1922), coauthored

with Hungarian Alfred Kemény, he advocated “to replace the static principle of

classical art with the dynamic principle of universal life.”

Moholy-Nagy also began to experiment with photograms, cameraless photographs made by placing objects directly onto the surface of light sensitive paper. Enthused by the creative and reproductive possibilities of the photographic medium, he would also go on to make photographs with a camera as well as photomontages, composite images intended to create new forms and meanings.

Moholy-Nagy also began to experiment with photograms, cameraless photographs made by placing objects directly onto the surface of light sensitive paper. Enthused by the creative and reproductive possibilities of the photographic medium, he would also go on to make photographs with a camera as well as photomontages, composite images intended to create new forms and meanings.

PROSPECTUS FOR BAUHAUS BOOKS, 1-14, 1928

Letterpress

Dimensions: 14.8 x 21 cm

Getty Research Center, Los Angeles

SPACE MODULATOR, 1939 - 1945

Oil and Incised Lines on Plexiglas, in Original Frame

Dimensions: Plexiglas: 63.2 × 66.7 cm; Frame: 88.6 × 93 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Oil and Incised Lines on Plexiglas, in Original Frame

Dimensions: Plexiglas: 63.2 × 66.7 cm; Frame: 88.6 × 93 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York

SPACE MODULATOR, 1939 - 1945 ( DETAIL )

PHOTOGRAM, CA. 1925-28, PRINTED 1929

Gelatin Silver Print (Enlargement From Photogram)

From

The Giedion-Mappe (Giedion Portfolio)

Dimensions: 40 x 30 cm - Frame: 45.4 x 37.8 x 3.2 cm

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum Purchase

Funded by the

Mary Kathryn Lynch Kurtz Charitable Lead Trust, The

Manfred Heiting Collection

A

In

1929, Moholy-Nagy enlarged several of his photograms from different

periods and published them in an edition for his Giedion Mappe, a portfolio of

ten images. Art historian Siegfried Giedion was a close friend of Moholy-Nagy’s

and passionate about modernist photography and its reproductive possibilities.

Believing that the size of his photogram images could be variable,

Moholy-Nagy created socalled repro-negatives for some of his unique photograms

and then printed them very large for exhibition purposes, approximating a

painting’s format; two other such examples are on view nearby.

SPACE MODULATOR CH FOR Y, 1942

Oil and Incised Lines on Formica

Dimensions: 154 x 60.5 cm

Collection of Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor,

Michigan

I KNOW NOTHING ABOUT IT, 1927

Photomontage (Gelatin Silver Print)

Dimensions: 22.5 x 17.1 cm - Frame: 50.5 x 37.8 x 3.5

cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

CONSTRUCTIONS: KESTNER PORTFOLIO 6, 1923

Lithograph, Edition of 50

Dimensions: 60 x 44 cm - Frame: 73 x 57.8 x 3.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired Through

the Publisher, 1981

CIRCUS AND SIDESHOW POSTER [THE BENEVOLENT GENTLEMEN],

1924

Photomontage (Gelatin Silver Print)

Dimensions: 28.1 x 20.3 cm - Frame: 57.5 x 42.2 x 3.5

cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

SPACE MODULATOR CH FOR R1, 1942

Oil and Incised Lines on Formica

Dimensions: 158 x 65 cm

Collection of Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor,

Michigan

PHOTOGRAM, CA. 1928-29

Gelatin Silver Print (Enlargement From a Photogram)

Dimensions: 38.7 x 29.9 cm - Frame: 51.8 x 41.8 x 2.8

cm

Galerie Berinson, Berlin

CH BEATA I, 1939 ( DETAIL )

PHOTOGRAM, 1939

Gelatin Silver Photogram

50.2 x 40.1 cm - Frame: 71.1 x 55.9 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Anonymous Gift

Installation View: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present,

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, May 27 -

September 7, 2016

Photo:

David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

PHOTOGRAM, CA. 1939-40

Gelatin Silver Photogram

Dimensions: 50.1 x 40.2 cm - Frame: 73.3 x 58.1 cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of George and Ruth

Barford

CH BEATA I, 1939

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 118.9 × 119.8 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A

Many

paintings that Moholy-Nagy made in the United States are titled with the

designation “CH,” which indicates Chicago. “Beata” may refer to a state of

happiness or relief at having reached his adopted city and country. There,

Moholy-Nagy developed a loose, organic, and gestural style in his work, while

still retaining his distinctive vocabulary of overlapping shapes,

transparencies, and dotted patterns that allude to the motifs in Light Prop for

an Electric Stage (Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne, 1930; recreated

2006), emphasizing the relationships among the various mediums with which he

was constantly experimenting.

PHOTOGRAM, 1943

Silver Photogram

50.4 x 40.5 cm - Frame: 64.9 x 80 x 4 cm

Musée National d’art moderne/Centre de Création

Industrielle,

Centre Pompidou, Paris, Purchased 1994

PHOTOGRAM, 1943 ( DETAIL)

PHOTOGRAPH (BERLIN RADIO TOWER), CA. 1928 - 1929

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 36 x 25.5 cm - Frame: 58.1 x 47.9 cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Julien Levy Collection,

Special Photography Acquisition Fund

“ Not

against technical progress, but with it. ”

László Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision: From Material to

Architecture (1930)

In

1923, Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus school of art and design,

invited Moholy-Nagy to join the faculty. Until 1928, Moholy-Nagy taught the

school’s preliminary course, with Josef Albers, and directed the metal

workshop. Joining the ranks of established artists Vasily Kandinsky and Paul

Klee, Moholy-Nagy’s appointment emphasized a change in the school’s direction,

as stipulated by Gropius, who advocated for the connection between art and

technology. In 1924, Moholy-Nagy’s third exhibition at Der Sturm in Berlin

included his industrially made enamel paintings, which caused a sensation among

his contemporaries.

Moholy-Nagy

published, along with Gropius, the Bauhaus Books series, a total of fourteen

volumes that gave voice to leading artists of the day. He collaborated with

designer Herbert Bayer—who promoted a

streamlined, “universal” alphabet—on eye-catching typography for Bauhaus

stationery, programs, announcements, and various advertising materials,

combining text and photography in an effort to convey a clear and direct

message. He continued to paint variations on geometric and architectural

compositions of intersecting planes and floating shapes and published lithographs,

in which he sought a “genuine space system, a dictionary for space

relationships.” He also made photomontages in a nod to the political and

provocative imagery of Berlin Dada, collecting materials from magazines and

newspapers and reassembling them in surprising combinations and narratives rich

with humor, political satire, and often mysterious meanings.

COVER FOR PHOTO-QUALITY, SPECIAL

ISSUE OF QUALITY 9, NOS. 1-2, 1931

Letterpress

Dimensions: 29.7 x 21 cm

Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

COVER AND DESIGN FOR WILL GROHMANN (THE COLLECTION OF

IDA BIENERT),

(POTSDAM: MULLER & L. KIEPENHEUER), 1933

Bound Volume

Dimensions: 25.7 x 19.5 cm

Collection of Michael Szarvasy, New York

LOVE THY NEIGHBOR / MURDER ON THE TRACKS (FILM

POSTER), 1925

Photomontage (Gelatin Silver Print)

Dimensions: 37.5 x 27 cm - Frame: 72.7 x 57.5 x 3.5 cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

WORK OF THE BUILDING GUILDS,

(BERLIN: VORWARTS BUCHDRUCKEREI) 1928

Letterpress

Dimensions: 29.8 x 21 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Jan Tschichold

Collection,

Gift of Philip Johnson, 1999

LEDA AND THE SWAN, 1925

Photomontage (Photomechanical Reproductions, Ink, and

Graphite) on Paper

Dimensions: 65 x 47 cm - Frame: 88.9 x 68.6 cm

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York,

Purchase with Funds From Eastman Kodak Company

INVITATION CARD FOR L. MOHOLY-NAGY: PAINTINGS,

DRAWINGS, CONSTRUCTIONS, LONDON, DECEMBER 31, 1936 - JANUARY 27, 1937

Letterpress

Dimensions: 12.7 x 20.3 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Jan Tschichold

Collection,

Gift of Philip Johnson, 1999

COVER & DESIGN FOR VISION IN MOTION ( PAUL THEOBALD, 1947 )

Bound Volume

Bound Volume

Dimensions: 28.6 × 22.9 cm

The Hilla von Rebay Foundation Archive

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

The Hilla von Rebay Foundation Archive

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM NEW YORK

SOLOMON

R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM NEW YORK

FRANK

LLOYD WRIGHT • ESTABLISHED IN 1939 • BUILT IN 1959

An

internationally renowned art museum and one of the most significant

architectural icons of the 20th century, the Guggenheim Museum in New York is

at once a vital cultural center, an educational institution, and the heart of

an international network of museums. Visitors can experience special

exhibitions of modern and contemporary art, lectures by artists and critics,

performances and film screenings, classes for teens and adults, and daily tours

of the galleries led by museum educators. Founded on a collection of early

modern masterpieces, the Guggenheim Museum today is an ever-evolving institution

devoted to the art of the 20th century and beyond.

ARCHITECTURE

In

1943, Frank Lloyd Wright was commissioned to design a building to house the

Museum of Non-Objective Painting, which had been established by the Solomon R.

Guggenheim Foundation in 1939. In a letter dated June 1, 1943, Hilla Rebay, the

curator of the foundation and director of the museum, instructed Wright, “I

want a temple of spirit, a monument!”

Wright’s

inverted-ziggurat design was not built until 1959. Numerous factors contributed

to this 16-year delay: modifications to the design (all told, the architect

produced 6 separate sets of plans and 749 drawings), the acquisition of

additional property, and the rising costs of building materials following World

War II. The death of the museum’s benefactor, Solomon R. Guggenheim, in 1949

further delayed the project. It was not until 1956 that construction of the

museum, renamed in Guggenheim’s memory, finally began.

Wright’s

masterpiece opened to the public on October 21, 1959, six months after his

death, and was immediately recognized as an architectural icon. The Solomon R.

Guggenheim Museum is arguably the most important building of Wright’s late

career. A monument to modernism, the unique architecture of the space, with its

spiral ramp riding to a domed skylight, continues to thrill visitors and

provide a unique forum for the presentation of contemporary art. In the words

of critic Paul Goldberger, “Wright’s building made it socially and culturally

acceptable for an architect to design a highly expressive, intensely personal

museum. In this sense almost every museum of our time is a child of the

Guggenheim.”

Wright’s

original plans for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum called for a ten-story

tower behind the smaller rotunda, to house galleries, offices, workrooms,

storage, and private studio apartments. Largely for financial reasons, Wright’s

proposed tower went unrealized. In 1990, Gwathmey Siegel & Associates

Architects revived the plan with its eight-story tower, which incorporates the

foundation and framing of a smaller 1968 annex designed by Frank Lloyd Wright’s

son-in-law, William Wesley Peters.

In

1992, after a major interior renovation, the museum reopened with the entire

original Wright building now devoted to exhibition space and completely open to

the public for the first time. The tower contains 4,750 square meters of new

and renovated gallery space, 130 square meters of new office space, a restored

restaurant, and retrofitted support and storage spaces. The tower’s simple

facade and grid pattern highlight Wright’s unique spiral design and serves as a

backdrop to the rising urban landscape behind the museum.

In

2008, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum was designated a National Historic

Landmark; in 2015, along with nine other buildings designed by Frank Lloyd

Wright, the building was nominated by the United States to be included in the

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World

Heritage List.

https://www.guggenheim.org/about-us

ARCHITECT FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM RESTAURANT

ARCHITECT FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM NEW YORK

NUCLEAR II, 1946

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 126.4 x 126.4 cm - Frame: 130.2 x 130.2 x

5.7 cm

Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of Kenneth Parker

PHOTOGRAM, 1926

Gelatin Silver Photogram

Dimensions: 23.8 x 17.8 cm

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Ralph M. Parsons Fund

A

At the

beginning of the twentieth century, tactile sensorial activities received a

great deal of attention across Europe. The sense of touch––and its derived

perceptions–– was often utilized in education methods and art practices. In his

photograms, Moholy-Nagy would occasionally use his extremities as

fortuitous elements interfering with the objects arranged on the

photosensitive sheets. In other works on view on this level, his palm and

fingers are distinctly outlined, sometimes revealing the details of his skin

texture as a result of the pressure exerted against the paper. The “hands

photograms” seem to be a tribute to the paramount importance of the body

and its role in creating art.

CONSTRUCTION IN ENAMEL 1, 1923

Porcelain Enamel on Steel

Dimensions: 94 x 60 cm - Frame: 116.9 x 81.1 x 8.2 cm

Collection of Victor and Marianne Langen

SRHO 1, 1936

Oil and Incised Lines on Rhodoid, on Original Painted

Panel

Dimensions: Rhodoid: 78.9 x 64.1 cm - Panel: 91.4 x

86.4 cm

Private Collection

THE EDIFICE OF THE WORLD, 1927

Photomontage (Photomechanical Reproductions, Ink, and

Graphite) on Paper

Dimensions: 64.9 x 49.2 cm - Frame: 88.9 x 68.6 cm

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York,

Purchase with Funds From Eastman Kodak Company

YELLOW

CIRCLE & BLACK SQUARE, 1921

The

Riklis Collection of McCrory Corporation

HOW DO I STAY YOUNG AND BEAUTIFUL?, 1925

Photomontage (Gelatin Silver Print)

Dimensions: 17.4 x 12.5 cm - Frame: 37.8 x 33.3 x 2.7

cm

Collection of Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Q XX, 1923

Oil on Panel

Dimensions: 79 x 69 cm - Frame: 81.5 x 72 x 6 cm

Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal, Germany

Y, CA. 1920–21

Gouache and Collage on Paper

Dimensions: 27.5 x 21.5 cm - Frame: 57.2 x 50.5 cm

Private Collection

“ As in

painting so in photography we have to learn to see, not the ‘picture,’ not the

narrow rendering of nature, but an ideal instrument of visual expression. ”

László Moholy-Nagy, Vision in Motion (1947)

Moholy-Nagy

believed his abstract paintings should not refer to anything in the real world,

but he thought photography and film could include representational subject

matter, and thus advocated for the necessity of working in various mediums.

Throughout the 1920s, photography took on an increasingly important role for

the artist as he embraced the idea of a “new vision,” a means of expressive

power through photographs taken from unconventional perspectives and

exaggerated viewpoints that could foster a new understanding of art in a

fast-changing culture. Moholy-Nagy’s wide range of subject matter includes

striking architectural viewpoints and arresting studies in texture, shadow, and

light. These reveal formal compositional and organizational principles as the

artist sought “new experiences of space” in his photographic work, just as he

sought similar qualities in his paintings. In the latter, MoholyNagy

experimented with various industrial materials, including the plastics Trolit

and Galalith, but from around 1928, he did much less painting

for several years, temporarily considering the medium to be too restrictive,

and instead focused on photography, design, and film.

In 1929–31, Moholy-Nagy participated in the exhibition Film und Foto (Fifo) as both a curator and exhibited photographer. This landmark presentation, which traveled across Europe and to Japan, emphasized the relationship of photography and film to society. Fifo was emblematic of Moholy-Nagy’s “new vision,” whereby unusual methods and techniques were hailed as the new means of creating art in an increasingly technological world. In 1930, he created his abstract film Light Play: Black-White-Gray (Ein Lichtspiel schwarz-weiß-grau), which showcased his Light Prop for an Electric Stage (Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne, 1930, recreated 2006) as its subject, illustrating his efforts to move from static painting to kinetic light displays in his desire to link different mediums.

In 1929–31, Moholy-Nagy participated in the exhibition Film und Foto (Fifo) as both a curator and exhibited photographer. This landmark presentation, which traveled across Europe and to Japan, emphasized the relationship of photography and film to society. Fifo was emblematic of Moholy-Nagy’s “new vision,” whereby unusual methods and techniques were hailed as the new means of creating art in an increasingly technological world. In 1930, he created his abstract film Light Play: Black-White-Gray (Ein Lichtspiel schwarz-weiß-grau), which showcased his Light Prop for an Electric Stage (Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne, 1930, recreated 2006) as its subject, illustrating his efforts to move from static painting to kinetic light displays in his desire to link different mediums.

Z VII, 1926

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 95.3 x 76.2 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Richard

S. Zeisler

SPACE MODULATOR L3, 1936

Oil on Perforated Zinc and Composition Board, with

Glass-Headed Pins

Dimensions: 43.8 x 48.6 cm - Frame: 46.4 x 51.4 x 6.4

cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Purchase 1947

A

In

Space Modulator L3, Moholy-Nagy intensified the work’s spatial ambiguity by

combining tiny perforations in the zinc sheet with projecting glass-headed

pins. Both elements generate shifting shadows that intermingle with the zinc

and the painted forms above and below, fusing light effects with physical

mediums

PAPMAC, 1943

Oil and Incised Lines on Plexiglas, in Original Frame

Dimensions: Plexiglas: 58.4 × 70.5 cm; Frame: 91.1 × 101.9 cm

Private collection

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Oil and Incised Lines on Plexiglas, in Original Frame

Dimensions: Plexiglas: 58.4 × 70.5 cm; Frame: 91.1 × 101.9 cm

Private collection

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A

Moholy-Nagy

achieved extraordinary effects in at least three works on sheets of flawed

Plexiglas, all on display on this level. During the manufacturing process,

overheating of the plastic can form bubbles, distortions, and other

imperfections on its surface. The flawed materials may have been

factory discards that were embraced by Moholy-Nagy due to the difficulty of

obtaining materials like Plexiglas, which were needed for the war effort.

He favored the defective materials and accentuated their ability to cast

shadows, exploiting the distortions and generating vibrating effects. The

evocative, playful title Papmac derives from the outmoded Hungarian

diminutive papmackska, a colorful tiger moth or caterpillar whose shape is

evoked by the defects in the plastic. In drawing attention to the

medium’s flaws, the title underscores their centrality to the work.

Installation View: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present,

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, May 27 -

September 7, 2016

Photo:

David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

PAPMAC, 1943 ( PAPMAC )

PHOTOGRAM, CA. 1925-28, PRINTED 1929

Gelatin Silver Print (Enlargement From Photogram)

From

The Giedion-Mappe (Giedion Portfolio)

Dimensions: 40 x 30 cm - Frame: 45.4 x 37.8 x 3.2 cm

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum Purchase

Funded by the

Mary Kathryn Lynch Kurtz Charitable Lead Trust, The

Manfred Heiting Collection

LEUK 4, 1945

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 124.7 x 124.7 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection

PHOTOGRAM, CA. 1925-28, PRINTED 1929

Gelatin Silver Print (Enlargement From Photogram)

From

The Giedion-Mappe (Giedion Portfolio)

Dimensions: 40 x 30 cm - Frame: 45.4 x 37.8 x 3.2 cm

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum Purchase

Funded by the

Mary Kathryn Lynch Kurtz Charitable Lead Trust, The

Manfred Heiting Collection

PHOTOGRAPH (BOATS), 1927

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 29.5 x 21.6 cm - Frame: 58.1 x 47.9 cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Julien Levy Collection,

Special Photography Acquisition Fund

NUCLEAR I, CH, 1945

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 96.5 x 76.2 cm - Frame: 116.8 x 96.5 x 7.6

cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Mary and Leigh

Block

PHOTOGRAPH (FROM THE RADIO TOWER, BERLIN), CA. 1928–29

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 34.7 x 26 cm - Frame: 52.1 x 44.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Anonymous Gift

B-10 SPACE MODULATOR, 1942

Oil and Incised Lines on Plexiglas, in Original Frame

Dimensions: Plexiglas: 42.9 × 29.2 cm; frame: 82.9 × 67.6 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Oil and Incised Lines on Plexiglas, in Original Frame

Dimensions: Plexiglas: 42.9 × 29.2 cm; frame: 82.9 × 67.6 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A

Moholy-Nagy

used the new material of Plexiglas—first introduced in the United States in

sheets in 1934—for his hybrids of painting and sculpture that he called Space

Modulators, of which there are several examples in this exhibition. The

reflective and transparent qualities of the material served his purpose to

modulate and activate light—his favorite medium—in order to create motion and

movement, often in unexpected ways. At times, he would manipulate the

Plexiglas, as with this work and others nearby, by heating the plastic sheets

(sometimes in his kitchen oven), and then shaping them by hand to enhance

their capacity to distort light and imply undulating movement.

“ An

education for personal growth. ”

László Moholy-Nagy, Vision in Motion (1947)

In

Berlin, where he had resettled in 1928 after having left the Bauhaus,

Moholy-Nagy turned to more commercial artistic pursuits, including advertising

design and typography, exhibition design for housing developments, and stage

design for the opera and theater, for which he created light projections.

In winter 1931, he met writer Sibyl Pietzsch, who became his second wife and

with whom he had two daughters. In 1934, because of the Nazis’ rise to power,

Moholy-Nagy left Berlin and found exhibition and advertising work in Amsterdam.

He collaborated there with De Stijl artists and architects, experimented with

color photography, designed for the magazine International Textiles, had

a solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, and lectured frequently.

In

spring 1935, Moholy-Nagy moved with his family to London, where he worked

mainly as a graphic designer, creating posters for the London Underground and

advertising materials for Imperial Airways and Isokon furniture. He continued

to create short, documentary-like films, explore the possibilities of color

photography, and experiment with industrial materials,

including aluminum and a range of plastics, as he pursued his research with

light and transparency. In July 1937, he sailed to the United States at the

invitation of the Association of Arts and Industries, which had been encouraged

by former Bauhaus director Walter Gropius to recruit him as the director of the

New Bauhaus in Chicago. The school was forced to close, for financial reasons,

after only one year. In February 1939, with the monetary and moral support of

Walter Paepcke, art collector and founder of the packaging company Container

Corporation of America, Moholy-Nagy reopened the school as the School of Design

(subsequently renamed the Institute of Design), which today is part of

the Illinois Institute of Technology. Alongside his work as an administrator

and fund-raiser, Moholy-Nagy continued to pursue his artistic practices,

including photograms, color photography, and the exploration of new materials,

such as Formica. Moholy-Nagy was especially intrigued by Plexiglas, whose

unique transparent properties would occupy him until the end of his life.

B-10 SPACE MODULATOR, 1942 (DETAIL)

PHOTOGRAM, 1943

Gelatin Silver Photogram

Dimensions: 25.5 x 20.4 cm - Frame: 66.2 x 51.2 x 2.5

cm

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

A II (CONSTRUCTION A II), 1924

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 115.8 × 136.5 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A

Moholy-Nagy

painted A II (Construction A II) soon after joining the faculty of the Bauhaus

school of art and design in Weimar, Germany. As if constructed around a mathematical

formula, the canvas is composed of two similar bodies of seemingly intersecting

planes and circles with a smaller structure hovering below a larger one, both

crossing through a white plane. Varying in degrees of perceived

transparency and color intensity, these shapes appear to overlap, forming an

architectural construction in space.

Installation View: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present,

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, May 27 - September 7, 2016

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

LOOK BEFORE YOU LEAP/SPORT MAKES YOU HUNGRY, 1927

Photomontage (Gelatin Silver Print)

Dimensions: 12.2 x 17.5 cm - Frame: 37.8 x 50.5 x 3.5

cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

DER STURM, VOLUME 14, NO 1, JANUARY 1923

Linocut Closed:

Dimensions: 20 x 14.4 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Library, New York

A

The

German art and literary magazine Der Sturm was the brainchild of the

multifaceted art critic and composer Herwarth Walden, who not only

established the influential Berlin gallery of the same name and this

periodical showcasing Expressionism, Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, and other modern

art movements, but also published artist portfolios and organized a forum for

lectures and experimental theater. Moholy-Nagy exhibited several times at

Der Sturm and published texts and woodcuts for the periodical.

PHOTOGRAPH (ELLEN FRANK), 1929

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 37 x 27.7 cm - Frame: 68.6 x 58.4 cm

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York,

Purchase with Funds From Eastman Kodak Company

DER STURM, VOL. 13, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 1922

Linocut

Dimensions: Closed: 17.3 x 16.5 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Library, New York

TYPOGRAPHIC COLLAGE, 1922

Collage on Paper

Dimensions: 27.2 x 38.1 cm - Frame: 39.7 x 59.7 x 2.7

cm

Collection of Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, Michigan

A

Typographic

Collage makes reference to Moholy-Nagy’s early Dada works that incorporate

letters and numbers. Here, however, he subverts legibility, placing letters

upside down and backward in a mysterious equation that––with its crisply

outlined sans-serif letters––appears as if it were readily comprehensible. This

collage also anticipates the distinctive book and letterhead designs

Moholy-Nagy would create at the Bauhaus, at times in collaboration with

director Walter Gropius and designer Herbert Bayer.

PHOTOGRAPH (SAILLING [HILDE HORN]), 1928

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 37.4 x 27.2 cm - Frame: 68.6 x 53.3 cm

George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York,

Purchase With Funds From Eastman Kodak Company

ADVERTISEMENT FOR ISOKON, CA. 1935 - 1936

Letterpress

Dimensions: 17.1 x 25.1 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Jan Tschichold

Collection,

Gift of Philip Johnson, 1999

OUR SIZES / OUR BIG MEN, 1924

Photomontage (Gelatin Silver Print)

Dimensions: 14 x 19.6 cm - Frame: 37.8 x 50.5 x 3.5 cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Installation View: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present,

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, May 27 - September 7, 2016

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

RADIO AND RAILWAY LANDSCAPE, 1919 - 1920

Oil on Burlap

73 x 50 cm - Frame: 77 x 52 cm

Private Collection

THE SHATTERED

MARRIAGE, 1925

Photomontage

(Gelatin Silver Print)

Dimensions:

16.5 x 12.1 cm - Frame: 50.5 x 37.8 x 3.5 cm

The J. Paul

Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Z VIII, 1924

Distemper and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 114 x 132 cm

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie

Desk Set with Parker 51 pen, 1939/46 Desk Set: Satin-Finished, Chrome-Plated

Brass, Magnetic Ball Holder, Designed by László Moholy-Nagy, 1946; Parker 51

pen:

Lucite Body with Gold Point and Small Components, Designed

by Kenneth

Parker and Marlin Baker, and Patented in 1939

23.6 x 15.4 x 4.3 cm

Collection of Susan M. Wirth, Milwaukee, LLC

A.XX, 1924

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 135.5 x 115 cm - Frame: 143.5 x 123 x 8 cm

Musée National D’art Moderne/Centre de Création

Industrielle, Centre Pompidou,

Paris, Gift of the Société des Amis du Musée National

D’art Moderne in 1962

CONSTRUCTION, 1922

Oil and Graphite on Panel

Dimensions: 54.3 x 45.6 cm - Frame: 70.8 x 62.2 x 10.8

cm

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of

Lydia

Dorner in Memory of Dr. Alexander Dorner

Installation View: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present,

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, May 27 - September 7, 2016

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

“ If

the unity of art can be established with all the subject matters taught and

exercised, then a real reconstruction of this world could be hoped for—more

balanced and less dangerous. ”

László Moholy-Nagy, “The Contribution of the Arts

to Social Reconstruction” (1943)

In his

final years, Moholy-Nagy continued to create art in various mediums and to

exhibit widely while he simultaneously pursued design work and shouldered the

manifold duties demanded of him to run his design school, which he called a

“laboratory for a new education.” He made some of his most original work

during this time, remaining faithful to his longtime fascination with the

mysteries of light, shadow, and transparency. He also explored the scientific

advances of the day, experimenting with 35 mm Kodachrome color film—still

in its infancy—and with plastics, as well as continuing his work with

photograms.

He

produced an array of explicitly autobiographical or narrative canvases—his Leuk

and Nuclear paintings—that allude to the cancer that would eventually

take his life in 1946 and to the horrors of the atomic bombings in Japan in

1945. Especially prominent in his late work are Plexiglas hybrids of painting

and sculpture, which he titled Space Modulators,

objects to be perceived as “vehicles for choreographed luminosity” that cast

special shadow effects.

Moholy-Nagy was always in pursuit of the “whole man,” seeking out new materials and methods in the steadfast belief that what mattered most were intellectual awareness and the necessity for the assimilation of art, technology, and education. From Europe, he brought his reputation and intellectual authority as well as his faith in humanity. Having arrived in America at a critical time between two world wars and on the cusp of significant artistic developments, he remained true to his vision as he paved the way for an increasingly interdisciplinary and multimedia age. The body of work on view in this exhibition exemplifies Moholy - Nagy’s commitment to the Gesamtwerk, or the total work, which he sought throughout his life, advocating for “the specific need of our time for a vision in motion.” These last three words became the title of his influential culminating text, which was published posthumously in 1947.

Moholy-Nagy was always in pursuit of the “whole man,” seeking out new materials and methods in the steadfast belief that what mattered most were intellectual awareness and the necessity for the assimilation of art, technology, and education. From Europe, he brought his reputation and intellectual authority as well as his faith in humanity. Having arrived in America at a critical time between two world wars and on the cusp of significant artistic developments, he remained true to his vision as he paved the way for an increasingly interdisciplinary and multimedia age. The body of work on view in this exhibition exemplifies Moholy - Nagy’s commitment to the Gesamtwerk, or the total work, which he sought throughout his life, advocating for “the specific need of our time for a vision in motion.” These last three words became the title of his influential culminating text, which was published posthumously in 1947.

ROOM OF THE PRESENT

Constructed in 2009 From Plans and Other Documentation Dated 1930. Mixed Media, Dimensions: 442 x 586.8 x 842.8 cm

Constructed in 2009 From Plans and Other Documentation Dated 1930. Mixed Media, Dimensions: 442 x 586.8 x 842.8 cm

Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven.

Foreground: Light Prop For an Electric Stage, 1930. Exhibition Replica, Constructed in 2006, Through the Courtesy of Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Foreground: Light Prop For an Electric Stage, 1930. Exhibition Replica, Constructed in 2006, Through the Courtesy of Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Metal, Plastics, Glass, Paint, and Wood, With Electric

Motor,

Dimensions: 151 x 70 x 70 cm.

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Hildegard

von Gontard Bequest Fund

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Installation view: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Installation view: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Photo:

David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

NICKEL SCULPTURE WITH SPIRAL, 1921

Nickel - Plated Iron, Welded

Nickel - Plated Iron, Welded

Dimensions: 35.9 x 17.5 x 23.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy 1956

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy 1956

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Installation view: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, Solomon R. Guggenheim

Installation view: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, Solomon R. Guggenheim

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

A

Moholy-Nagy

believed new materials called for a new kind of art. The metal construction of

Nickel Sculpture with Spiral, which was included in the artist’s first exhibition

at the Berlin gallery Der Sturm in 1922, gave it a specifically modern nature

that appealed to artists and critics for its connection to industry. A

nod to Constructivism, the work exemplifies Moholy-Nagy’s dedication to

industrial materials, and its outwardly spiraling form embodies dynamic

energy and motion.

PHOTOGRAPHS

Moholy-Nagy

photographed several iconic modern structures, including the Eiffel Tower

in Paris, the intricate steel transporter bridge in Marseille, and the Berlin

Radio Tower. Shot variously from exaggerated angles, dramatic viewpoints, and

plunging perspectives, the images of the radio tower and bridge are

emblematic of the artist’s “new vision,” a way of looking at photography as an

independent means of artistic expression, offering multiple sensorial and

aesthetic possibilities, as an embodiment of modernity. These photographs

also appear to be exercises in abstraction and line drawing, as

well as explorations of the interplay between light and shadow.

PHOTOGRAPH ( LIGHT PROP ), 1930

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 24 x 18.1 cm - Frame: 50.5 x 37.8 x 3.5 cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

ROOM OF THE PRESENT

Constructed in 2009 From Plans & Other

Documentation Dated 1930. Mixed Media

Dimensions: 442 x 586.8 x 842.8 cm.

Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Installation View: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Installation View: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

A

ROOM OF

THE PRESENT

Based

on the few existing plans, drawings, and related correspondence Moholy-Nagy

left behind, Room of the Present—unrealized in the artist’s lifetime—was

constructed in 2009 by designers Kai-Uwe Hemken and Jakob Gebert for presentation

in several European museums.

Room of

the Present exemplifies Moholy-Nagy’s desire to achieve the Gesamtwerk, or the

total work, unifying art, technology, science, and film with life itself.

Alexander Dorner, the ambitious young director of the Provincial Museum

in Hannover, Germany, was inspired by MoholyNagy’s contribution to the annual

salon of the Société des artistes décorateurs (Society of Decorative Artists)

in Paris in 1930. For the German section of the salon, Moholy-Nagy designed

Room 2 (Salle 2), which served as the model for Room of the Present, along with

other exhibition designs. Dorner was keen on devising a new concept for the

modern museum by rearranging art collections into “atmosphere rooms” in an

effort to break from traditional installation practices and challenge the

viewer with an appreciation for contemporary art. Intrigued by Moholy-Nagy’s

use of photography, film, and light effects, Dorner invited him to design

a comparable room for his museum.

Room of

the Present would have included the most recent cultural developments in

photography reproductions, films, slides, documents, and replicas of

architecture, theater, and industrial design. Only one original object would

have been included, Moholy-Nagy’s motor-driven light display apparatus Light

Prop for an Electric Stage (Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne, 1930;

recreated 2006), as the vehicle for the projection of fluctuating luminous

effects. Also on view would have been films by Viking Eggeling, Sergei

Eisenstein, and Dziga Vertov.

Though

Room of the Present was never realized due to logistical and financial

difficulties and the increasingly unstable political climate in Germany, it

represented, in concept, Dorner and Moholy-Nagy’s thinking about the power of

images and of the broad dissemination of knowledge and information. Intended as

a hybrid between a museum gallery and a work of art, it would have served as

what Moholy-Nagy described as an “arena of mass communication that would

transform modern life.” Here, Room of the Present includes photographic

panorama boards and loops, slide and film projection screens, movable panels

with examples of typography, design objects, an educational text, and a replica

of Light Prop for an Electric Stage placed inside a box in the center of the

gallery, as originally envisaged by the artist.

TILLED FIELDS PAINTING, CA. 1920–21

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 64.5 x 75.5 cm - Frame: 71.5 x 81.2 x 6 cm

Albertina, Vienna, on Permanent Loan From the Forberg

Collection

G5: 1923–26, 1926

Oil and Graphite on Galalith

Dimensions: 42 x 52.7 cm - Frame:.2 x 66 x 6.7 cm

Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Collection

Société Anonyme

PHOTOGRAM, 1922

Gelatin Silver Photogram on Printing - Out Paper

Dimensions: 13.7 x 8.7 cm

Private Collection

A

While

Moholy-Nagy explored form, light, and transparency in his “glass architecture”

paintings that reflected his interest in modern German architecture, he began

to create photographic images without a camera, producing what he called

“photograms.” On view here are some of his earliest photograms, created

by superimposing materials in a variety of shapes, textures, and translucencies

on photographic paper and then exposing the paper to light. As he

described it, the technique allowed him to “sketch with light in the same way

the painter works in a sovereign manner on the canvas with his own instruments

of paintbrush or pigment,” creating weightless images rich in their interplay

of light, shadow, and tonal variety. Moholy-Nagy considered light to be “a new

plastic medium just as color in painting and tone in music.”

CIRCLE SEGMENTS, 1921

Tempera on Canvas

Dimensions: 78 x 60 cm

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

A

The

influence of Constructivism’s emphasis on simple geometric shapes is

evident in the paintings seen here; all three illustrate how Moholy-Nagy

achieves an equilibrium of forms and colors and creates innovative spatial

relationships. Around this time, his paintings also began to assume

enigmatically short and impersonal titles composed of combinations of letters

and numbers. Circle Segments was once owned by the German art collector

and patron Ida Bienert, whose collection also included works by Marc Chagall,

Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Kazimir Malevich, and Piet Mondrian. A copy of the

catalogue of her private collection, designed by Moholy-Nagy, is on view on

Rotunda Level 4.

K VII,

1922

PHOTOGRAM, 1922 (DETAIL)

COVER AND DESIGN FOR LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY,

OSKAR SCHLEMMER, AND FARKAS MOLNAR

(The Theater of the Bauhaus), Bauhaus Books , 4

(Munich: Albert Langen Verlag), 1925

Bound Volume

Dimensions: 23 x 18 cm

Collection of Richard S. Frary

A

Distinguished

by their font and imagery, the fourteen books published by the Bauhaus were

written, for the most part, by the school’s staff and aimed to bring

architecture, pedagogy, theater, design, photography, and art to a broad and

international public. In The Theater of the Bauhaus, produced with Oskar

Schlemmer and Farkas Molnár, Moholy-Nagy proposed ideas for a new form of total

theater in which light plays a central role and “must undergo even greater

transformation in this respect than sound.” Particularly influential, Painting

Photography Film identifies the new role of photography and its relationship to

painting that was considered to be outmoded, conveying how technological

developments created

new forms of creativity and advocating for artists to work with the current

means available. Published after MoholyNagy left the Bauhaus, and the last in

the series, From Material to Architecture spells out his pedagogical program

for painting, sculpture, and architecture, and discusses how light can be used

as a formal medium.

CH 7, 1941 CHICAGO SPACE 7, 1941

Oil and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 120 x 120 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection

CONSTRUCTION AL6, 1933–34

Oil and Incised Lines on Aluminum

Oil and Incised Lines on Aluminum

Dimensions: 60 × 50 cm

IVAM, Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Generalitat

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

IVAM, Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Generalitat

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A

Moholy-Nagy

wrote that when unfiltered light penetrates through perforations—in

conjunction with painted effects—“a kind of spatial kinetics also begins to

play its part,” because the work appears to move as the viewer walks past. The

layering of painted shapes that mimic the contours of the shifting shadows of

the holes creates a dynamic visual experience that blurs the distinction

between material and immaterial; “light and pigment . . . [become] fused into a

new unity.”

DUAL FORM WITH CHROMIUM RODS, 1946

Plexiglas and Chrome - Plated Brass

Plexiglas and Chrome - Plated Brass

Dimensions: 92.7 × 121.6 × 55.9 cm

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst,

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Installation View: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, Solomon R. Guggenheim

Installation View: Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, Solomon R. Guggenheim

Photo:

David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

PHOTOGRAPH (STUDIO WING OF THE BAUHAUS BUILDING/

BAUHAUS BALCONIES) 1927

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 24.6 x 17.9 cm - Frame: 51.8 x 41.8 x 2.8

cm

Galerie Berinson, Berlin

A

Photograph

(Studio Wing of the Bauhaus Building/Bauhaus Balconies) is a negative print

from a series of iconic images of the balconies of the Bauhaus

school in Dessau, where Moholy-Nagy taught from 1925 to 1928. The

black-and-white contrast––inherent to the effect of the negative print––and the

drastic bottom-up perspective enhance the Constructivist composition. The

architectural elements as well as the human figure silhouetted on the top

of the balconies create intersecting diagonals, recalling the artist’s

abstract paintings.

COVER & DESIGN FOR VISION IN MOTION ( PAUL

THEOBALD, 1947 )

Bound Volume

Bound Volume

Dimensions: 28.6 × 22.9 cm

The Hilla von Rebay Foundation Archive

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

The Hilla von Rebay Foundation Archive

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/

Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York

PHOTOGRAPH (STUDIO WING OF THE BAUHAUS BUILDING/

BAUHAUS BALCONIES) 1927 (DETAIL)

CURATOR KAROLE P. B. VAIL

LASZLO

MOHOLY - NAGY

László

Moholy-Nagy (b. 1895, Borsód, Austria-Hungary; d. 1946, Chicago) believed in

the potential of art as a vehicle for social transformation, working hand in

hand with technology for the betterment of humanity. A restless innovator,

Moholy-Nagy experimented with a wide variety of mediums, moving fluidly between

the fine and applied arts in pursuit of his quest to illuminate the

interrelatedness of life, art, and technology. An artist, educator, and writer

who defied categorization, he expressed his theories in numerous influential

writings that continue to inspire artists and designers today. Walter Gropius

invited him to join the faculty at the Bauhaus school of art and design, where

Moholy-Nagy taught in Weimar and Dessau in the 1920s. In 1937, he was appointed

to head the New Bauhaus in Chicago; he later opened his own School of Design

there (subsequently renamed the Institute of Design), which today is part of

the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Among

Moholy-Nagy’s radical innovations were his experiments with cameraless

photographs (which he dubbed “photograms”); his unconventional use of

industrial materials in painting and sculpture; experiments with light,

transparency, space, and motion across mediums; and his work at the forefront

of abstraction, as he strove to reshape the role of the artist in the

modern world. Moholy-Nagy: Future Present features paintings, sculptures,

collages, drawings, prints, films, photograms, photographs, photomontages,

projections, documentation, and examples of graphic, advertising, and stage

design drawn from public and private collections across Europe and the United

States.

On

display in the museum’s High Gallery is Room of the Present (Raum der

Gegenwart), a contemporary fabrication of an exhibition space conceived of by

Moholy-Nagy in 1930, but not realized in his lifetime. On view for the

first time in the United States, the large-scale work contains photographic

reproductions and design replicas as well as his kinetic Light Prop for

an Electric Stage (Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Bühne, 1930;

recreated 2006). Room of the Present illustrates Moholy-Nagy’s belief in the

power of images and the significance of the various means with which to

view and disseminate them—a highly relevant paradigm in today’s constantly

shifting and evolving technological world.

Moholy-Nagy

is a central figure in the history of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. In

1929, Solomon R. Guggenheim and his advisor, German-born artist Hilla

Rebay, began collecting his paintings, works on paper, and sculpture in

depth for the Guggenheim’s growing collection of nonobjective art. His work

held a special place at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting—the

forerunner of the Guggenheim Museum—where a memorial exhibition was

presented shortly after his untimely death in 1946.