PAUL KLEE: THE THINKING EYE

PAUL KLEE: THE THINKING

EYE BY GIULIO CARLO ARGAN

The writings

which compose Paul Klee’s theory of form production and pictorial

form have the same importance and the same meaning for modern art as

had Leonardo’s writings which composed his theory of painting for

Renaissance art. Like the latter, they do not constitute a true and proper

treatise, that is to say, a collection of stylistic and technical rules, but

are the result of an introspective analysis which the artist engages in during

his work and in the light of the experience of reality which comes to him in

the course of his work. This analysis which accompanies and controls the

formation of a work of art is a necessary component of the artistic process,

the aim and the finality of which are brought to light by it. This explains too

how the experience of reality which is acquired in seeking aesthetic value is

no less concrete or less conclusive than that which is acquired in scientific

or philosophic research.

It is

well-known that Klee, more than any other artist of our century, was

consciously detached from the main stream of modern art and its theoretical

assumptions. In the same way, Leonardo, more than any other artist of the

Renaissance, consciously detached himself from the central features of the

historical tradition. In their creative thought both Leonardo and Klee are not

so much concerned with the art object, as with the manner in which it is

produced. They are concerned not with form as an immutable value, but with

formation as a process. Both are aware that the artist’s approach or creative

manner is an independent and complete way of existing in reality and of understanding

it; and as they are not unaware that there are other speculative methods, they

are led to investigate that particular character which is the distinctive

feature of the artistic approach, always bearing in mind, however, that this

must develop over the whole field of experience. For this reason Leonardo’s

mode of thought, like that of Klee, covers every aspect of being; it takes in

the entire universe. Since art brings into being, albeit only through what is

termed the visible, a cosmic awareness of reality, there is no moment or aspect

of being which can be considered foreign or irrelevant to the experience which

is acquired in artistic creation.

Historically

speaking, Klee’s poetics can be linked to what might be called the poetics of

contradiction, that is to say, poetics from Mallarme to Rilke. Klee was a

friend of the latter; and Klee’s thoughts on art were linked by at least two

sources of common interest to the poetics of Mallarm: Wagner, whom as a

passionate lover of music he knew very well, and Poe, who certainly was one of

the sources of his pictorial inspiration.

The

fundamental themes are always those of non-positivity, of elusiveness, of the

uncertainty of existence, of the emptiness of reality, and the need to fill

that void by human endeavour and artistic creation. Nor are these born of an

imperious creative will, but of the contradiction which exists between an

understanding of the anguished uncertainty of everything and our

indestructible awareness of existing, and of existing by necessity in one time,

in one space, and in one world.

Everything

that we know of reality (and this reality includes ourselves, the clear world

of our consciousness and that murky and crepuscular world of the unconscious)

comes to us through this tormented paradox. Nor is it a single and grandiose

image which imposes itself on us by the logical system of its eternal values,

but a hasty sequence of images, often dissociated and enigmatic, and always

fragmentary throughout the full cycle of our existence. In turn, our existence

is no more in its time-space reality than that self-same succession of images:

and there is no moment of our existence which is not an experience of reality.

These ambiguous images, then, are formed by ourselves. It is almost as if we evoke

them from the darkness of a lost dimension, and reanimate them by the rhythm of

our actions, giving them meaning and form. For the threat does not come from

the vitality of the unconscious, but on the contrary, from carrying within us

something, that is dead, which, being corrupted, corrupts us. This endeavour,

therefore, and this , endeavour alone, is the subject of a speculation on art.

Perhaps, like

Mallarme, Klee too dreamt of the absolute work of art, ’l’oeuvre’, and did not

achieve it; his real work must be found in the mass of evidence testifying to

his life of research, in his development by way of a vast number of fragments,

in his rapid sequence of paintings, in page after page of sketches and notes,

in the restless technical experiments (since every technique is an attempt at

‘trying’, a ‘coup de des’ that may even succeed in eliminating ’le

hasard’).

The writings

which compose Klee’s theory of form are, in fact, an attempt to fix the moments

of that unaccomplished creative work, which unwinds with the devouring rapidity

of time; to give meaning to arbitrary images, releasing them from the

changeability of events and from shapelessness. These writings, therefore, more

than any commentary, are a live and necessary part of the artist’s ceuvre . Since

they cannot be separated from the drawings which accompany them they cannot be

separated either from his other pictorial and graphic works, from the various

planes on which his works were being simultaneously developed, from

the inevitable irregularity of his progress or from the coherence, no less

severe for being full of the unexpected, of his intellectual adventure. Klee’s

poetics, however, have this special quality, that in a large measure they are

born and are formulated as didactics, like a well-prepared course of teaching

given in a school with syllabuses and purposes precisely defined, as was the

Bauhaus of Weimar and of Dessau. Of all the artists of this century, Klee is

perhaps the one who has most purposefully penetrated into the enchanted realm

of fantasy. It is as if he were seeking, whilst exploring the unconscious, the

manifestation of an absolutely authentic and unique experience in which he

would find himself alone in the suffering of the lonely ego, even reaching out

to that ultimate and finally truthful manifestation of the ego which only comes

to us at the moment of death. It cannot therefore be wondered at that his most

constant preoccupation was to be able to communicate his own experience so that

it could be repeatable and ‘utilisable’ and finally productive. Nor is this

all: this man who looks upon nothingness with such a candid and dauntless eye,

who ‘toys' with death like Schiller’s artist ’toys’ with life, employs his own

poetics and his own didactics in a school which not only has a social and

somewhat revolutionary syllabus, and sees In technology the new strict

spirituality of the modern world, but proposes to intervene effectually in the

existing state of affairs by forming a class of technical executives and

planners capable of solving problems arising from industrial production and

capitalist economy.

Klee always wanted to

teach and he dedicated himself to the school with an almost apostolic fervour.

Conscious that art should be a means of human communication, he saw in teaching,

in the exactness of the didactic method, a strict means of human communication.

It is a matter of teaching others how to walk along thin invisible wires,

stretched out in the darkness, trying to penetrate an unknown dimension. There

can be no other way than that of going forward together along the uncertain

road. There is the need not to be alone, to hold hands, to make a human chain:

this is still the human basis, sentimental perhaps, of Klee’s didactics.

But other and

more serious reasons impel his poetics to become didactic and to assume a

methodological character. According to Klee, the manner in which the artist

creates implies, above all, a didactic requirement, for it is through creation

that the artist learns to recognise the world in which he exists and acts,

shaping it according to the extent of his own experience. Reading the pages of

his theory of form it would appear that Klee desired to penetrate to the very

depths of his knowledge of the universe; he speaks of space and time, of forces

of gravity, of centrifugal and centripetal forces, of creation and destruction

of the being, of the individual and the cosmos. Side by side with strangely

happy

intuitions, with par&scientific propositions, with paradoxical postulates

and with a vast quantity of very valuable annotations relating to the daily

routine of pictorial work, one finds recollections of readings, passages

revealing knowledge (which is neither superficial nor second-hand) of

contemporary currents of thought, psychology of form, theory of visibility,

psychoanalysis, the philosophy of phenomenology. Certainly all this does not

constitute a system, but it does reveal a complicated construction in which

everything seems to find its proper place.

Nothing is

further from the artist’s mind than the assumption that he is producing a

scientific work, what is important to him is to specify a dimension or a

perspective, to recognise the limits of space and time in which one’s own

existence manifests itself, to reweave the weft of the universe, from the

starting point of one’s own ego, with its will to make or to shape.

Thus, he

thinks, must the world appear to those who do not stand apart from it and

contemplate it from outside; to those who see it from the inside, with its

infinite prospects, its diverging paths which cross, wheel round, then open

slowly along the apparently capricious curves of life's parabola; a world ever

eccentric and peripheral, ‘irregular’ , yet nevertheless secretly obedient to

certain laws, and ever striving to develop in order to find its path and break

through to reality.

Thus space

(and here we may note the similarity with the thought of Husserl and Heidegger)

will no longer be a logical sequence of planes but above-below-in front-behind-

Ieft- right in relation to the ‘l’ in space; time will no longer be a uniform

progression, but in a before and after relation to the ‘l’ in time; and as

nothing is static, that which is now in front, soon will be behind, and that

which is now before will be after.

Space and

time are simultaneously subjective and objective; for this reason the sequence

of values is endless and each value is not permanently bound to the object, but

to the existence of the object in this or that point of space and time. It is

bound to the recollection of its having been, to the possibility of its future

being, under completely different conditions of space and time. The object

itself has no certainty; it might have been and might be no longer; it might

not be, but might be going to be. Since it is, ultimately, only a meeting of

co-ordinate lines, a luminous point in the dark expanse of possible space and

time, it could change into another object, whose trajectory may come to pass

through that point. Should the unforeseeable parabola of our life pass through that

point it could be that we might ‘become’ that object. Reality is a never-ending

metamorphosis; this is a thought Klee had inherited from Bosch, and shared with

Kafka.

There is,

however, something which differentiates man’s being and his actions,

which differentiates cyclic changes of history from the unconscious

changes and happenings in reality, something which, in the formal instability

of metamorphosis, succeeds in isolating and defining forms and in making

definite points of light.

It is the aim

and the will of humanity somehow to control its own destiny, to know itself and

clearly to establish its position in the confusion of chaos. Finally to ‘save

itself’, if this expression still means something when confronted with an empty

void. Nothingness, which stretches beyond the horizons of life, impels man

ineluctably to find a solution here and now, within the uncertainty of the

particular state of his society and of the individual within society.

The main

thread which unravels itself throughout the whole of Klee’s theory is the

search for quality; it is in the search for quality, namely the search for

one’s own absolute authenticity, that mankind (as Kierkegaard would say)

desires desperately to find in order to justify itself, and, perhaps, to save

itself.

But it is not

enough to desire this; to do or to become is life itself and it is only by

acting consciously, and methodically, that one can attain some

quality or value, which is also the value of existence, a full consciousness of

each moment of it.

It may be

said that Klee’s art and theory represent an attempt to reconstruct the

world according to values of quality; and since these values are not

given and are embedded in layers of false experience, it becomes necessary to

distil these values by a transformation, a 'reduction to quality’ of the

quantities. In other words, it becomes necessary to reduce progressively the

conglomeration of quantitative phenomena which fill the universe and human

existence, to the point of that irreducible and immutable minimum, which in

fact represents quality, and which is to be found in all things which are real,

although revealed only in meditation and in the production of works of art.

Notice how

perspective, which is the typical quantitative construction of space, is

elaborated in both Klee's painting and theory: or note the almost alchemistic

treatment through which the chromatic scores emerge from the quantitative

graduation of chiaroscuro, seeking in each note not just purity of tone, but

the critical point of the passage from tonal volume to quality of timbre. The

true meaning of this unceasing metamorphosis is therefore this: quantities are

continually being raised to the level of qualities; and since this level is the

level of consciousness, this last transformation can only take place in the

mind of man. This is the humanistic foundation of Klee’s art and

doctrine.

The quality value will

only be reached finally when the form produced, or the art object, contains

within itself all human experience, the sum of human experience since the

beginning ,of time. The work of art will be, even so, an object closed within

its own finality, but it will project itself upon the spatial horizon of the

universe and the temporal horizon of humanity. The work of art, since quality

possesses individual character, must be elaborated by the individual, but it

will acquire a collective meaning; its power will be incommensurable, its

active presence will never be erased from the world. The artist’s work, though

it proceeds according to his own rhythm, will intertwine itself with the work

of all mankind. ‘ We wish to be exact, but without limitations’; limitation is

logic and calculation which determine the mechanism of modern productive

techniques, the techniques of industry. We do not wish to destroy these

techniques which possess almost unlimited possibilities: we want to develop

them into more subtle and penetrating techniques harnessing both action and

knowledge, manual and mental activity.

The Bauhaus

had a definite programme: to restore production, which industrial techniques

had developed only in a quantitative sense, to the search for quality values,

in this way preserving autonomy, the creative possibility of a real existence,

and, finally, the freedom of the individual in a society which was tending more

and more to become a compact and uniform mass. But what are these quality

values? The attitude of the Bauhaus on this point was ambiguous: in the first

period at Weimar, following in the wake of the Werkbund, themes and procedures

characteristic of ancient craftmanship were re-elaborated in an attempt to

reduce traditional aesthetic values to a schematic system which could be

applied to new industrial techniques. In the second period at Dessau, following

the example of the Dutch group De Stijl, quality was sought in formal abstract

concepts, in a mathematical rationalisation of the form selected as the image

of the supreme rational quality of the human being.

Research,

however, remained dialectically linked with the question of quantities; in the

first instance attention was concentrated on an attempt to preserve certain

traditional aesthetic values, whilst increasing the quantity of production; in

the second instance, quality was transposed to the level of conceptual

abstraction, leaving to production the task of mass-producing the model. It was

precisely on this point - whether to conceive quality as a mere model or as a

value which manifests itself and remains inherent in the object - that there

arose the famous conflict between Walter Gropius and Theo van

Doesburg:

this was one of the factors which caused the Bauhaus to change its programme to

a more constructive level.

Klee was in

fact the man who gave the search for quality a completely new basis, and made

it a search for an autonomous and absolute value, which, though derived from

quantity, is irrelevant to quantity itself. Quality for him was the ultimate

product of the individual’s unrepeatable and unique experience; one achieves it

by descending into the depths and by progressively clarifying the secret

springs of one's actions, the myths and recollections lurking in the

unconscious which strongly influence consciousness and action.

One must

reach out for the point of prefiguration, the agony of death already suffered,

without which there can be no completeness of existence or experience. The

world we leave behind in this descent (which is also an ascent to superior

spiritual forms) is the world of quantities, the dead world of forms already

used, the world of logic, of positive science, of the masses, of politics, the

three-dimensional world, in which everything assumes proportional and

quantitative relations, the world of social classes characterised by degrees of

power.

The world of

qualities which opens out the more one descends into the unconscious depths, is

not the world of forms already dead and established, but the world of nascent

form, of formation, of Gestaltung: it is the world of unending organic

relations which are born of real encounters and are measured by the effective

strength which each image develops in its particular condition of space and

time.

And since it

is no longer admissible to draw any distinction between an object which is real

and one which is imaginary, each image, being a moment of experience and of

existence, is no longer a fixed and detached representation but preserves

almost physical vitality. The transition from lower or passive forms,

traditions or habits or remembrances which hamper man’s freedom (Husserl calls

them 'So-sein'), to superior forms, in which freedom has its highest

expression, that is to say creation, is accomplished in the image.

The image will continue

to live in the world as a representation of the moment of the individual’s

authentic existence, of his existence in the world. It will be the password

among individuals, a vital link amongst the members of a community.

Klee never

loses sight of other men, the community; he always tries to consider society as

a single and multiform individual, with its own life story, its own ‘Erlebnis’.

Unlike Mondrian he does not conceive of an idea! society, which finally and

peacefully settles down into a common acceptance of incontrovertible rational

truths; he prefers to seek the reasons for common understanding in living

experience, in the history and pre-history of humanity, of the ‘people’,

instead of in utopian plans for the future.

In society,

individuals appear to him to be bound together by old ties, by the spirit of

clan and tribe, by a host of beliefs and terrors, of myths, magical rites,

superstitions and taboos; these are the ties which unite them organically to

nature and the cosmos.

By

understanding his own motives, the individual does not isolate himself in his

own monad; on the contrary, he re-discovers in the myths of the unconscious the

common roots of man’s being and his existence. Not only does he discover the

relationship, but the unity of the one with the whole. In the world of quality,

the mythical images shed all nocturnal shadows and become as clear as platonic

ideas. The passive genesis (as Husserl would say), which collides with memory

and matter, becomes active genesis. A new solidarity is established,

independent of the objective rationality of certain accepted rules, but

dependent on the discovery of a common origin and common ancestors; an origin

which renews itself each moment, transmuting death into birth and giving to

action a genuine creative meaning.

The vast

cosmological vision evolved in Klee’s theory does not supply the key to the

symbolic or semantic interpretation of the images and signs which appear in his

paintings: it rather explains how each one of those images, each of those

signs, contains a truth which each man will read according to his own

experience and will find a place for in the rhythm of his own existence, and

yet retains the same value of truth for everyone. Klee anticipates Adorno’s thesis

of ‘Alienation’ and seeks the maximum ‘alienation’ or ‘consumption’ of artistic

value in a maximum of quality and purity, in the elimination of all formal

schemes, in the conquest of value which possesses both clarity of form as well

as multiplicity and transmutability of meanings, the vitality, the capacity to

associate itself with everyday life, which are characteristic of the image. The

association with everyday life, the possibility of the work of art existing on

a practical plane: this is another theme which links Klee’s poetics with the

Bauhaus didactics.

It was Marcel

Breuer who perceived the real significance of Klee’s teaching at the Bauhaus;

to Breuer we owe the fact that Klee’s world of images has become an essential

component of what is known as industrial design. The tubular furniture invented

by Breuer in 1925, thread-like, suspended in improbable yet faultless

equilibrium, precise and mechanical gadgets animated by a silent and vaguely

ambiguous vitality, as if from one moment to another they might re-enter and

dissolve into the space which they do not occupy, is certainly born of Klee's

nervous and intense graphics, and the currents of strength which he infuses

into his lines. This furniture inhabits man’s space like Klee’s images inhabit

the space of his slanting and oblique perspectives, and of the mobile depths of

his tonal layers. This furniture too is born of an invisible dynamic of space,

and whilst fulfilling its function with impeccable accuracy, traces a new

dimension in which relations are clarified, and values are brought to the

purity and transparency of quality.

The capacity

of the image or of the object-image (and every image is already an object) in

no way contradicts the rational faith of the Bauhaus. If rationality is not an

abstract formula, but the character of existence and human action, then the

final distillation of experience which is achieved in art, in the ultimate

analysis, is the work of a rational being. Klee’s didactic aim and, in a wider

sense, the exemplary educative meaning of ail his work is to show how, through

all the meditation and active creation which constitutes artistic activity,

experience performs ever widening circles until finally it touches the

furthermost limits of the universe and returns to the point of maximum

intensity, that is, the point of formation, of Gestaftung, where each sign

signifies at the same time the individual and the world, the present and all

time.

.......................................................................................

...................................

...............................................

.............................................................

Giulio Carlo

Argan

" New work is preparing itself; the demoniacal shall be

melted into simultaneity with the celestial, the dualism shall not be treated

as such, but in its complementary oneness. The conviction is al- ready present.

The demoniacal is already peeking through here and there and cant be kept down.

For truth asks that all elements be present at once. It is questionable how far

this can be achieved in my circumstances, which are only halfway favorable. Yet

even the briefest moment if it is a good one, can produce a document of a neiv

pitch of intensity. "

PAUL KLEE

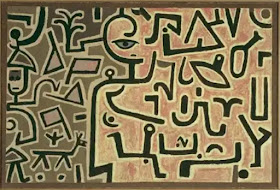

AND ASHAMED, 1939

Gouache and Watercolor on

Paper Mounted on Board

Dimensions: 22.7 ×

29.5 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

RED HOUSE, 1929

Oil on Canvas Mounted on

Cardboard

Dimensions: 25.4 ×

27.6 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

PAVILION

OF NUMBERS, 1918

Watercolour

and Pen and Ink on Paper

Dimensions: 16.3 x 8.9 cm.

© 2019 Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

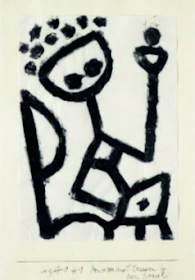

SIBLINGS, 1930

DAME DEMON, 1935

Oil and Watercolour on

Prepared Hessian Canvas on Card

Dimensions: 150 × 100 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

MUTTER & KIND, 1938

Aquarell auf Grundierung

auf Jute

Dimensions: 560 x 520 mm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

OR THE

MOCKED MOCKER, 1930

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 43.2 x 52.4 cm

Credit: Gift of J. B.

Neumann

© 2019 Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

A

YOUNG LADY’S ADVENTURE, 1922

Watercolour

on Paper

Dimensions: Support: 625 x 480 mm

Frame: 686 x 510 x 20 mm

Frame: 686 x 510 x 20 mm

Collection:

Tate

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

CONQUEST OF THE MOUNTAIN,

1939

Oil on Cotton

Dimensions: 95 × 70 cm

LA BELLE JARDINIERE, 1939

Oil and Tempera on

Hessian Canvas

Dimensions: 95 × 71

cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

MAGIC GARDEN, 1926

Oil on Plaster-Filled Wire Mesh in Artist's Frame

Dimensions: Plaster: 52.1 x 42.2 cm; Frame: 53 x 45.1 cm

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Peggy Guggenheim

Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn

Magic Garden was

executed in 1926, the year Paul Klee resumed teaching at the Bauhaus at its new location in Dessau. During his Bauhaus period

he articulated and taught a complex theoretical program that was supported and

clarified by his painting and drawing. Theory, in turn, served to elucidate his

art. Based on probing investigation and carefully recorded observation, his

work in both areas reveals analogies among the properties of natural, of

man-made, and of geometric forms.

Studies of plants

illustrating growth processes appear often in Klee’s notebooks as well as in

his paintings and drawings. He was also interested in architecture and combined

images of buildings with vegetal forms in Magic Garden and

several other works of 1926. Pictorial motifs often arise from geometric

exercises: the goblet shape that dominates the lower center of this composition

appeared also in a nonrepresentational drawing exploring the development from

point to line to surface to volume.

The surface Klee

creates with the medium of Magic Garden resembles that of a

primordial substance worn and textured by its own history. A cosmic eruption

seems to have spewed forth forms that are morphologically related but

differentiated into various genera. Although excused from the laws of gravity,

each of these forms occupies a designated place in a new universe,

simultaneously as fixed and mobile as the orbits of planets or the nuclei of

organic cells. Klee’s cosmic statements are gleefully irreverent; he writes of

his work: “Ethical gravity rules, along with hobgoblin laughter at the learned

ones.”̯

Lucy Flint

1. Quoted in W. Grohmann, Paul Klee, New York, 1954, p. 191.

INSULA DULCAMARA, 1938

Oil and ColourGlue Paint

on Paper on Hessian Canvas

Dimensions: 88 × 176 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

EXUBERANCE, 1939

Oil and ColourGlue Paint

on Paper on Hessian Canvas

Dimensions: 101 × 130 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

DAY MUSIC FROM ART

D’AUJOURD’HUI, ART OF TODAY, MASTERS OF

ABSTRACT ART: ALBUM 1953

( ORIGINAL COMPOSITION EXECUTED IN 1940 )

One From a Portfolio of

Sixteen Screenprint Reproductions

After Paintings and

Drawings

Dimensions: Composition

(irreg.): 35 × 52.4

cm); Sheet: 49 × 63.9 cm

cm); Sheet: 49 × 63.9 cm

Publisher: Édition Art

d'Aujourd'hui, Boulogne - Edition 300

Credit: The Louis E.

Stern Collection

© 2019 Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

SHIPS

IN THE DARK, 1927

Oil

Paint on Canvas

Dimensions: Support: 427 x 590 mm

Collection:

Lent From a Private Collection 2011

On Long Term Loan

On Long Term Loan

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

THE VASE, 1938

Oil on Burlap on Burlap

Dimensions: 88 ×

54.5 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

GRAPHIK. ERSTE MAPPE.

MEISTER DES

STAATLICHENBAUHAUSES IN WEIMAR, 1921

Lithograph in Colors, on

Stiff Wove Paper

Dimensions: 38.7 ×

26.4 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

CHANT D’AMOUR A LA

NOUVELLE LUNE, 1939

Watercolour on Hessian

Canvas

Dimensions: 100 ×

700 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

SENECIO, 1922

Oil on Canvas

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

SUNSET,

1930

Oil

on Canvas

Dimensions: 46.1 × 70.5 cm

Credit

Line: Gift of Mary and Leigh Block

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Paul Klee was an artist and teacher at

the Bauhaus for most of that famed school’s existence. Initially head of the

bookbinding department, Klee made his greatest contribution as a lecturer on

the theory of form in art for the basic design course. There, he developed his

ideas about the “polyphony” of painting—the simultaneous effect of formal

elements that produces “a transformed beholder of art.”

Klee was also a trained musician and

shared with many artists of the early twentieth century the idea that music was

the key to producing a new, abstract art. He was interested in the temporal

character of music and its possible translation into forms of art. Works like Sunset reflect

the principles of rhythm: linear structures, forms, and tonal values are

orchestrated into a measured, vibrating image. To produce such a harmonious

effect, Klee layered an intricate pattern of dots over a neutral background.

Abstract, geometric, and overlapping shapes balance with recognizable forms,

such as the schematic face in the upper left and the red sun and arrow in the

lower right. The resulting composition—balancing stillness and movement,

shallowness and depth—relates to Klee’s larger project of looking to music to

produce an art that “does not reproduce the visible, but makes visible.”

FOREST WITCHES, 1938

Oil on Paper on Burlap

Dimensions: 99 × 74

cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

RISING STAR, 1931

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 63 × 50

cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

UNTITLED, CAPTIVE /

FIGURE OF THIS WORLD – NEXT WORLD, CA. 1940

Oil and Coloured Paste on

Primed Burlap on Burlap

Dimensions: 55.2 ×

50.1 cm

Dimensions: Fondation Beyeler

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

MASQUE DE (JEUNE) =

COMEDIEN, 1924

Oil on Canvas on Card

Nailed to Wood

Dimensions: 36.7 ×

33.8 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

DER VERLIEBTE, 1923

Color Lithograph

Dimensions: 27.4 ×

19.1 cm

This is an Edition

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

FIGURE

OF THE ORIENTAL THEATER, 1934

The

Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

Courtesy of the Phillips Collection.

THEY'RE BITING, 1920

Watercolour

and Oil Paint on Paper

Dimensions: 311 x 235 mm

Collection:

Tate

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

DER EXKAISER, 1921

Oil Transfer, Watercolor

and Gouache on

Paper Laid on Artist's

Mount

Dimensions: 36.5 ×

28.6 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

THE BRIGHT

SIDE POSTCARD FOR

‘’

BAUHAUS EXHIBITION WEIMAR 1923 ‘’

Lithograph

Dimensions: 9.8 x 14.4 cm; Sheet: 10.4 x 15 cm

Cream,

Smooth, Wove (Board).

©

2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

IN THE CURRENT SIX

THRESHOLDS, 1929

Oil and Tempera on Canvas

An assiduous student of

music, nature, mathematics, and science, Klee applied this constellation of

interests to his art at every turn. Even his purely abstract works have their

own particular subject matter. In the Current Six Thresholds,

an austere composition of horizontal chromatic stripes divided into smaller

units and intersected by vertical bands, has been compared to landscape

painting. A late Bauhaus work,

it is part of a series of grid like canvases that Klee painted after he

returned from a trip to Egypt. His visual impressions of the Nile river valley

are represented here through a highly schematized, geometric analogy composed

of a square lattice motif and restrained tonal variations. Another geometric

painting, New Harmony, demonstrates the artist’s long-standing interest in

color theory. Such flat configurations of painted rectangles appeared in Klee’s

work as early as 1915 and evolved as expressions of his equation of chromatic

division with musical notation. This late canvas, painted in 1936, is the last

such composition and, in typical Klee fashion, looks toward the new and

innovative, rather than nostalgically backward. According to art historian

Andrew Kagan, the composition is based on the principle of bilateral inverted

symmetry (the right side of the canvas is an upside-down reflection of the left)

and the tonal distribution of juxtaposed, noncomplementary colors evokes the

nonthematic, monodic 12-tone music of Arnold Schönberg. Kagan notes, in

conjunction with this reading, that Klee used 12 hues in New Harmony, save

for the neutral gray and the black underpainting.

Klee revealed a more socially and politically relevant side in his 1937 painting Revolution of the Viaduct, of which the Guggenheim’s Arches of the Bridge Break Ranks is an earlier version. Created when Fascism was on the rise in Europe, the image of rebellious arches escaping from the conformity of a viaduct invokes public dissension while promoting individuality. It is a flippant but foreboding reference to Albert Speer’s monolithic Nazi architecture as well as to official Soviet imagery of workers marching forward in unison. There is a poignant postscript to Klee’s social critique: after the artist fled Germany in 1937 to his native Switzerland, 17 of his works were displayed in the Nazis’ Degenerate Art exhibition, a show of Modern painting and sculpture that they considered too free-spirited and libertarian.

Klee revealed a more socially and politically relevant side in his 1937 painting Revolution of the Viaduct, of which the Guggenheim’s Arches of the Bridge Break Ranks is an earlier version. Created when Fascism was on the rise in Europe, the image of rebellious arches escaping from the conformity of a viaduct invokes public dissension while promoting individuality. It is a flippant but foreboding reference to Albert Speer’s monolithic Nazi architecture as well as to official Soviet imagery of workers marching forward in unison. There is a poignant postscript to Klee’s social critique: after the artist fled Germany in 1937 to his native Switzerland, 17 of his works were displayed in the Nazis’ Degenerate Art exhibition, a show of Modern painting and sculpture that they considered too free-spirited and libertarian.

Nancy Spector

Etching

Dimensions: image: 12.4 x

13.7 cm; Plate: 15.2 x 16.5 cm;

Sheet: 15.9 x 17.5 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R.

Guggenheim Museum, New York Estate of

Karl Nierendorf, By

purchase

© 2018 Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

GAZE OF SILENCE, 1932

Oil on Burlap

Dimensions: 55.6 ×

70.5 cm

© Artists Rights Society

(ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

TROPICAL GARDEN, 1923

Watercolor and Oil

Transfer Drawing on Paper, with Watercolor on Cardboard Mount

Dimensions: Sheet: 17.9 x

45.5 cm; Mount: 24.5 x 56.5 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum,

New York Solomon R.

Guggenheim Founding Collection, By Gift

© 2018 Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

COMEDY, 1921

Watercolour

and Oil Paint on Paper

Dimensions: Support: 305 x 454 mm

Frame: 572 x 685 x 20 mm

Frame: 572 x 685 x 20 mm

Collection:

Tate

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

PAUL KLEE 1879 – 1940: A RETROSPECTIVE

EXHIBITION CATALOG

BLACK KNIGHT, 1927

INTENTION, 1938

Couloured Paste on Paper

on Burlap

Dimensions: 755 x 1123 mm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

HORSE AND MAN, 1925

Oil Transfer, Ink, and

Watercolor on Paper Mounted on Board

Dimensions: 34 × 50.2 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENTAL

PLAN FOR LATE FALL, 1922

Watercolor With Ink on

Paper

Dimensions: 18.9 × 30.6 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

ZENTRUM PAUL KLEE

ZENTRUM PAUL KLEE

With around 4'000 works at its disposal the Zentrum Paul Klee has the most significant collection of paintings, aquarelles and drawings world-wide and includes archive and biographical material from all the periods of Paul Klee’s work.

A principal task of the Zentrum Paul Klee is to ensure that the artistic, pedagogic and theoretical work of Paul Klee as well as its significance within the cultural and social context of its time, is scientifically developed and communicated through different channels and media.

By posing topical questions, new scientific interpretations and innovative forms of communication, the Zentrum Paul Klee aims to bring Paul Klee’s artistic potential into the present.

Visitors are able to gather stimulating experiences and discoveries. This should motivate to a more intense understanding of Klee’s work and personality, artistic insight in general and to each individual’s cultural life.

Through its activities the Zentrum Paul Klee is established as the competence centre worldwide for the research and the communication of the life and work of Paul Klee, the history of its effect and other culturally relevant themes. It maintains an efficient and modern research infrastructure and develops distinctive proposals for exhibition and communication programmes, in accordance with scientific demands as well as the expectations of visitors of different age groups, biographical backgrounds and cultural interests.

For this purpose

- Rooms of high aesthetic and functional quality for the presentation of temporary exhibitions are available,

- The open and public accessible zone of the Museumsstrasse encourages a critical look at art by means of various media as well as the encounter between art and art enthusiasts,

- A generously conceived activity area for children, young people and adults encourages the development of their own creativity,

- An auditorium with ideal conditions for musical experiences is maintained,

- Modern equipped rooms for events and seminars are available to deal with themes on subject matter from the most varied areas of culture, science and business,

- The building designed by architect Renzo Piano and its surroundings offer a unique symbiosis of nature and culture.

The Zentrum Paul Klee was made possible through the founder families Klee and Müller, the authorities and the sovereign power of the City, the Canton and Burgergemeinde Bern as well as partners from business.

The concrete activities of the Zentrum Paul Klee are derived from the statutes of the Foundation of the Zentrum Paul Klee and are orientated toward realising the subsidy agreement with the Canton Berne, the City of Berne and the communities of the Regional Conference of Bern-Mittelland, the guidelines of the International Council of Museums ICOM as well as internal business regulations. As an institution, only partially supported by public funds, the Zentrum Paul Klee adheres in its business activities, especially in the declaration of accounts, to the imperative principles of transparency and submits to regular controls through the subsidisers.

http://www.zpk.org/en/service-navigation/about-us/concept-104.html

ZENTRUM KLEE ARCITECTURE

The beautiful piece of land, with the Villa Schöngrün and

the Schosshalde graveyard with the grave of Paul Klee in the immediate

vicinity, seemed as though created for the construction of a museum which would

accommodate the complete work of the Paul Klee Foundation. The idea of

combining nature and architecture in an exciting relationship to one another,

met with the best premise here.

The idea

From the outset it was clear to Piano that the artist Paul

Klee has «a too broad, too large breath», for him to be locked up into a

«normal building». For the vision of his own work Renzo Piano allowed himself

to be inspired by the identity of the place, the gently curved line of the

terrain. That the motorway was also there, with a deep cut abruptly restricting

the building site, did not disturb him. As a «Life line» of our civilisation it

would be properly integrated into the project and find its aesthetic-functional

echo here. It is very different at the back of the building: in order that the

unity of nature and the architecture is not disturbed, it was also his explicit

wish that the area around the building should be used as farm land and not

converted into a park.

The hills

Renzo Piano noticed that the hills in the foreground stand

like scenery in front of the horizon of the wooded hills in the background. The

three hills blend as terrain contours with the ground and make the entire area

into a landscape sculpture. As an artistic structure in its own right it houses

the new cultural institution. Seen from the motorway the unusual roof structure

is only visible for about ten seconds. Coming from the park it is not

immediately clear whether the three curves are artificial or just natural. Only

when in front of the main facade are the dimensions apparent: the middle curve

is 12 metres high, the glass front to the motorway over 150 metres long.

The wish that the Zentrum should not only be a «Place of

remembrance», but also an interchange between encounter, relaxation and

enjoyment, Renzo Piano solved by spreading the Zentrum over three hills.

Starting from Klee’s numerous different activities as painter, musician,

teacher, writer and philosopher the aim of the Zentrum Paul Klee is to present

the artist comprehensively in this complexity. As a result each of the three

hills has its own task. The North Hill is used for the practice of art

education, for music, the conferences and the workshops, the Middle Hill for

displaying the collection and the changing exhibitions, the South Hill for

research and administration.

The exhibition rooms

The overall capacity and diversity of the collection make it

impossible to show all the works at one time. The particular sensitivity of

Klee’s works also prevents any classical type of exhibition, in which the same

works are always shown unchanged. Instead the Zentrum Paul Klee presents the

works which belong to it in a regularly changing selection of about 120 to 150

works, which each time stand under a changing theme. Two exhibition rooms

provide space for constantly new examinations of the works of Klee and the

presentation of differing manifestations of visual art.

The Museum Street

The construction of the Zentrum is at the same time

functional and highly technical. Directly behind the main facade of glass is

the public area, the so-called Museum Street. This back-bone zone runs parallel

to the motorway, is bright, sometimes noisy and for the visitors the only means

of connection between the three hills. On entering the exhibition rooms, the

noisy mood changes into quiet observation.

The lighting

Klee’s works are mostly pencil drawings and water colours,

which may only be exposed to a maximum of 50 to 100 Lumens. The main hall in

the Middle Hill is a pure artificially lit room, like the exhibition hall on

the lower floor of the building. The basic lighting is installed in the vault

of the steel girders, which shines indirectly onto the roof of the room. The

individual pictures are emphasised by spots. The day-light which comes in

through the whole glass facade is controlled and dampened by means of an

automatic sun protection system.

The façade

One consequence of the building’s unusual geometry is the

intricate design used for the 150 metre long glass façade. The façade is

divided into an upper and lower section along its entire length. The two façade

sections are marginally offset and connected by the canopy (the roof of the

Museum Street) at a height of 4 metres above the level of the ground floor. The

glass façade measures 19 metres at its highest points, and the largest panes of

glass weigh almost half a metric ton and measure 6 x 1.6 metres.

Earthworks

In spite of the impressive dimensions of the three hills

large sections of the Zentrum Paul Klee are actually situated on the

underground floors. This fact is made clear by the 180,000 cubic metres of

earth that have been moved since 15 October 2001, involving some 15,000 truck

movements on the site, and by the 1,100 tonnes of steel girders, 1,000 tonnes

of reinforcing steel and 10,000 cubic metres of concrete put into place.

RENZO PIANO BUILDING WORKSHOP

Renzo Piano Building Workshop company profile The Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW) is an international architectural practice with offices in Paris and Genoa.

The Workshop is led by 13 partners, including founder and Pritzker Prize laureate, architect Renzo Piano. The company permanently employs nearly 130 people. Our 90-plus architects are from all around the world, each selected for their experience, enthusiasm and calibre.

The company’s staff has the expertise to provide full architectural design services, from concept design stage to construction supervision. Our design skills also include interior design, town planning and urban design, landscape design and exhibition design services.

Since its formation in 1981, RPBW has successfully undertaken and completed over 120 projects across Europe, North America, Australasia and East Asia. Among its best known works are: the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas; the Kansai International Airport Terminal Building in Osaka; the Kanak Cultural Center in New Caledonia; the Beyeler Foundation in Basel; the Rome Auditorium; the Maison Hermès in Tokyo; the Morgan Library and the New York Times Building in New York City; and the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. Recently completed works include the Shard in London, and the new Whitney Museum in New York.

The quality of RPBW’s work has been recognised by over 70 design awards, including major awards from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

In all our work we aim to address the specific features and potential of a particular situation, embracing them into the project while responding to the requirements of the program. We continue to push the limits of building technology – innovating, refining and experimenting – to come up with the very best solution for each situation.

Our method of working is highly participatory, with clients, engineers and specialist consultants all contributing from the beginning of a project and throughout the design process.

Our approach to design is not strictly conventional and involves the use of physical models and one-to-one scale mockups to help test and develop our proposed design concepts. We also believe that the design process is not linear and that it requires architects to think and draw on different scales at the same time, considering each finished detail in the development of the overall design.

ZENTRUM PAUL KLEE

BLUMENMYTHOS

( FLOWER MYTH ), 1918 - 1982

Watercolour on a Pastel Sketch on Gauze on

Watercolour on a Pastel Sketch on Gauze on

Newspaper

on Silver-Bronze Paper on Cardboard

Dimensions: 29 x

15.8 cm

© Sprengel

Museum Hannover

PORTRAIT AN EQUILIBRIST

1927

Oil and Collage on Cardboard Over Wood With Painted Plaster Border

Dimensions: 63.2 x 40 cm

Credit: Mrs. Simon

Guggenheim Fund

© 2019 Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

THE

SUBLIME SIDE POSTCARD FOR

‘’

BAUHAUS EXHIBITION WEIMAR 1923 ‘’

Lithograph

Dimensions: Composition: 14.3 x 7.4 cm; Sheet: 15 x 10.5 cm

Cream,

Smooth, Wove (Board).

©

2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

PAUL

KLEE TO LILY KLEE, 1932

Oil

and Paste Paint on Paper on Jute

Orginal

Frame Strips

Dimensions: 100 x 70 cm

©

2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

DISPUTE, 1929

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 670 x 670 mm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

A PRIZE CREEP, 1939

Colored Crayon on Paper

Dimensions: 21 × 34.9 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Ink and Watercolor on

Paper, with Watercolor on Cardboard Mount

Dimensions: sheet: 16.2 x

17.4 cm; Mount: 27.4 x 27.4 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum,

New York Estate of Karl

Nierendorf, By Purchase

© 2018 Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

SCHERZO

WITH THIRTEEN, 1922

Oil

Transfer Drawing, Watercolor, Ink, and

Pencil

on Paper on Board

Dimensions: 27.9 x 35.9 cm

Laid

Paper Mounted on Board

©

2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

SEILTANZER, 1923

Color Lithograph on Laid

Paper With Deckle Edges

Dimensions: 43.4 × 26.9 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

BURDENED CHILDREN, 1930

Graphite,

Crayon and Ink on Paper on Board

Dimensions: 650 x 458 mm

Collection:

Tate

Bequeathed

by Elly Kahnweiler 1991 to Form Part of the Gift of

Paul Klee worked on

small scale, creating microcosmic worlds in drawings, watercolours and oils.

Frequently creations of the imagination and often childlike in their apparent

simplicity and directness, his pictures were nonetheless rooted in acute

observations of the natural world, human behaviour and an appreciation of the

small, unremarked incidents of everyday life.

Klee’s appointment in 1921 as a teacher at

the Bauhaus in Weimar

introduced a new phase in his art. He began to formulate a more theoretical

approach, giving his art a rational basis as a counterweight to the power of

intuition. His pedagogical notebooks formed the basis of lectures and of

several essays he wrote in the early 1920s, in which he explored the

fundamental components of his creative process: line, tone-value and colour.

However, Klee still believed that theory was but a means to an end.

Burdened Children illustrates the manner in

which Klee elaborated elements of these fundamental principles. ‘I begin where

all pictorial form begins: with a

point that sets itself in motion.’ (Quoted in Spiller 1961, p.24.) This drawing

demonstrates the movement from a point to a line, which in turn creates planar

forms. It consists of an almost unbroken line that forms a series of

round-cornered, interlocking boxes. Klee then added stick legs and eyes to give

the shapes a human character. It was unusual for Klee to have given the two

figures such heavy outlines, a feature chiefly associated with his work in the

later 1930s. However, the heavy black might have been one reason for giving the

drawing its title. Klee clearly found something unusual in this composition, because he made five

different variants in different media. Of these, the closest

in compositional elements to this work is Twins, 1930 (present location

unknown), although Klee filled the inner planes of the figures with a

combination of shading, hatching and dots.

HERO MOTHER, 1927

Watercolor, Ink, and

Graphite on Paper Mounted on Board

48.6 × 31.3 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

RUNNER AT THE GOAL, 1921

Watercolor and Graphite

on Paper, Mounted on

Cardboard with Gouache

Border

Dimensions: 39.4 x

30.2 cm overall

Solomon R. Guggenheim

Museum, New York Estate of Karl Nierendorf, By purchase

© 2018 Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

THE PRINCE & HIS

TOWN, 1925

Watercolour and Pen in

Ink, Partially Sprayed on

French Ingres Paper

Mounted on Backing Cardboard.

Dimensions: 49.5 ×

34.5 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

RAYÉ DE LA LISTE, 1933

Oil on Paper on Card

Dimensions: 31.5 × 24 cm

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

/ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

PRESENTATION DE MIRACLE,

1916

Gouache, Pen and Ink on

Prepared Fabric, Mounted on Card

Dimensions: 29.2 ×

23.6 cm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

ANIMALS

MEET, 1938

Oil

and Color With Glue on Cardboard on Polywood

Dimensions: 420 x 505 mm

©

2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

A POLYPHONIC PAINTING:

PAUL KLEE & RHYTHM BY ELIANE ESCOUBAS

In an article

from 1912, Klee situates himself in the context of expressionism as opposed to

impressionism:

‘’ Both

invoke a decisive moment in the genesis of the work: for impressionism this is

the instant in which the impression of nature is received, whereas for

expressionism, it is the subsequent instant, that in which the received

impression is rendered. Impressionism stops with the observation of form,

rather than rising to its active construction. ‘’

And he adds a

few lines later:

‘’ One

particular branch of expressionism is represented by cubism. 1 ‘’

Thus for

Klee, a painting will not depict states of feeling, but rather will be an

active construction. But what does this notion of "construction"

imply? It essentially adds a sense of temporal unfolding that the impressionist

painting lacks, as the famous " Schopferische Konfession " of 1918

makes clear:

‘’ Is a

painting ever born in a single moment? Certainly not! It is built up little by

little, no differently than a house. And does the spectator make a tour of the

work in an instant?

( Often yes,

alas... ) On the side of the spectator also, the principal activity is

temporal.... The artwork is movement, it is itself a fixed movement, and is

perceived in movement

( the eye-muscles

). 2 ‘’

If time is a

fundamental principle of the pictorial work, then its proximity to the musical

work is evident. And Klee specifies:

‘’ The

musical work has the advantage of being perceived in the exact order of

succession in which it had been conceived, whereas the plastic work presents

the uninformed with the difficulty of not knowing where to begin. To the

informed spectator, however, it presents the advantage of being able to vary

the order of its reading and thus to become aware of its multiple meanings. 3 ‘’

The pictorial

work is thus not an object but an event. It does not have the fixity of an

object; and to look at it is to allow oneself to be taken along varied and

often unknown paths, that are " set up " in the work. This is why Klee

declares: " The singular optical path no longer responds to today's needs.

" 4

There would

be, then, a difference between the optical eye and the pictorial eye. If the

optical eye is insufficient, then what kind of eye is at issue in painting? Is

it the haptic eye, a vision touching, as Riegl defines it in Questions of

Style? Not this either. Let us, for the moment, designate it as the "

musical eye. " We will encounter this again and again in the course of our

analyses.

This is why

Klee speaks of a " plastic polyphony, " 5 in " Schopferische

Konfession, " describing it as follows: " The separation of the

elements of form, and their arrangement in subdivisions; the dislocation of

this order and the reconstruction of a totality on all sides simultaneously;

plastic polyphony, the achievement of repose through the equilibrium of

movement, so many questions decisive for the science of forms, but not yet art

in the supreme sense, " adding that " polyphonic painting is superior

to music in the sense that the temporal element is present in it as a spatial

given. " 6

If, as he

writes in 1928, " to draw and to paint is to learn to see behind a facade,

to grasp something underlying, to recognize the underlying forces, to unveil,

" 7 then we shall hypothesize that it is "rhythm," as movement

and time, as subjacent force, that is to be unveiled and produced. Rhythm would

be this arch-sensibility, this implication of time and of movement, whose

fundamental determination we find in Henri Maldiney's analyses in " The

Aesthetics of Rhythm ": " Art is the truth of the sensible because

rhythm is the truth of aisthesis. "

In order to

define rhythm, Maldiney appeals to the analyses of the Greek ruth mos as

Benveniste elaborates it:

‘’ The Greek

ruth mos does mean form in the sense of schema, but a particular kind of form

that is different from the schema. Whereas the schema is fixed, realized form,

posited as an object, ruthmos designates form in the instant in which it is

taken up by that which is moving, fluid. It is improvised, momentary,

modifiable form. 8 ‘’

In addition

to Maldiney's analyses, we shall also refer to Pierre Sauvanet's studies in his

two-volume work Le rythme et la raison. There, the author elaborates three

criteria of analysis which he presents as "combinatorial criteria":

structure (or schema ), periodicity ( periodos ), and movement [metabole):

"The rhythmical, in the strong sense, is both discontinuous and regular

(periodicity), while allowing for a margin of irregularity (movement), and

presenting itself globally as a continuity (the ensemble

structure-periodicity-movement)." He then calls rhythm " any

perceived phenomenon to which one can attribute at least two of these three

criteria." 9

CONSTRUCTION: TECTONIC

FORMS AND ENERGETIC FORMS

To construct,

for Klee, is to produce a structure. For our part, we shall speak of

"

tectonic " and " energetic " forms. In a painting, we shall

suggest, two sorts of forms are articulated, juxtaposed, mixed or opposed. The

tectonic forms are lines of construction ( folds, breaks, frames, dislocations,

interlacings, stratifications, etc. ); the others, the energetic forms, are

lines of force ( weights, attractions, contractions, elevations, shocks, stops,

and suspensions ). And these forms are not figurative forms: they are not

necessarily the outlines that delimit figures or that streak across their

surfaces. They are not necessarily objectival lines, but lines along which the

gaze is led lines that thereby " construct " the gaze.

What then is

to be understood by " construction," and by " structure " ?

Klee's first

works are drawings and engravings: from 1901 to 1905, he creates a cycle of

eleven etchings entitled Inventions, which are a sort of deconstruction of

natural structures. These are the famous caricatures, deformed figures—almost

monstrously so—the " de-figured, " so to speak, such as the Two Men

Meet, Each Supposing the Other to Be of Higher Rank ( Zwei Manner, einander in

hoherer Stellung vermutend, begegnen sich ), Winged Hero ( Held m. Flugel ), or

Aged Phoenix ( Greiser Phonix ). Here we find dislocation and deformation at

the same time as construction. A construction that de-forms, a de-formation

that constructs. For Klee, the issue is one of abandoning the re-production of

the object. And what is more evident in caricature than the abandonment of this

reproduction? Grimacing figures, disproportions, contortions, different kinds

of anamorphosis, or as he writes: " the exaggeration of the ugly parts of

the model. " Seemingly arbitrary deformations of natural reality; in his

journal he mentions

Bocklin and

Goya as his inspirations.

This is also

why Klee recognizes his proximity to cubism, which, according to him, is (as we

have seen) " a branch of expressionism." However, that in cubism to

which he is attached, that which will become important later, is what he will

call " numerical determination ":

‘’ The

cubists for their part push numerical determination to the smallest details....

Cubist reflection rests essentially on the reduction of all proportion and

culminates in primordial forms, like the triangle, rectangle, and the circle. 10

Of course,

with the etchings entitled Inventions, Klee has not yet arrived at the "

primordial forms " of the cubists—but he will discover them. And the

statement so often repeated since that time, " art does not reproduce the

visible, it renders visible, " could, on a first reading (although this is

not the only one possible), refer back to these deformations, these numerical

determinations, reductions, and distortions.

No doubt, the

superb series of drawings of angels from1939, from the end of Klee's life, can

also be classified under this genre of " deformation. "

Yet these

caricatures, like the later Angels, are not static, deformed forms, but rather

what Klee calls dynamical forms. They are what Klee, in his Bauhaus lectures,

calls

"

structural rhythms ": "the most primitive structural rhythms based on

repetition of one sole unity in the sense of left-right or up-down." This

is a remarkable formulation insofar as it concerns precisely the notion of

structure as " dividual assemblage, " which is to say as divisible

assemblage—which is precisely the situation with numerical elements. 11 But

what are we to understand by " structural rhythms "? We must go back

to the Bauhaus course and " On Modern Art, " which

concentrates the advances the course makes.

We can

reconstitute the unfolding of structure in pictorialterms. Klee writes: "

I begin logically from chaos." 12

Now, chaos is

represented by the point, the point without breadth (geometrically defined as

the intersection of two lines). If I place the tip of my pencil on the point

then it becomes a line: " From the dead point, the initiation of the first

act of mobility (line). " 13 The exit from chaos is by definition a "

movement. " If I prolong the line and produce other lines, I have a

surface. Point, line, surface: " the specific elements of graphical art

are points and energies, linear, planiform and spatial. " 14

Are we

re-discovering, here, a Cartesian space, defined by " figure and movement

"? Perhaps, and yet Klee's lines and sur faces have a number of very

different aspects. Thus, in a sort of dream narrated a little after having

described these " acts of mobility, " he writes:

‘’ The most

diverse lines. Stains, blurred strokes, smooth, striated, blurred surfaces.

Undulating movement. Inhibited movement. Articulated, counter movement.

Braiding, weaving, masonry. Imbrication. Solo. Multiple voices. Disappearing

lines in the process of being reactivated (dynamism). 15 ‘’

This will be

an " orchestra of forms " for the eye. In this space, " The eye

must graze the surface, absorb it piece by piece. " 16 Thus, the

horizontal and the vertical are set in place:

‘’ The

vertical is the right path, the upright position or the balance of the animal.

The horizontal designates its extent, its horizon. Each one is an entirely

terrestrial affair, static. 17 ‘’

Furthermore,

the upright human position is represented by the plumb line—oriented toward the

center of the earth, for weight is the fundamental law of the terrestrial:

everything falls. In order to avoid falling, there is only movement: an upright

person will advance a foot, offset a leg in order not to stumble, not to lose

balance. 18 Walking is the only way of not losing balance: it is a balancing

that is constantly wavering and being re-established.

A slight nudge

to the plumb line and it begins to oscillate like a pendulum. 19

Whence a

fundamental law for Klee (as well as for cubism): balance is not symmetry. Nor

is it only alternation: the tightrope walker with his balancing rod is an

example of the constant conquest of equilibrium. These are what Klee calls

"non-symmetrical balances" made of dissemblance and difference. It is

necessary to insist on this: the fundamental notion of balance or equilibrium

that is not symmetry. This is what underlies not only the critique of

perspectival painting (geometrical perspective founded on symmetry), but it is

also what becomes the central notion of modern painting. Again: the fundamental

law of modern painting is expressed thus: balance is not symmetry—this law, as

we shall see, will be crucial to the understanding of the notion of rhythm.

Turning now

to what Klee calls the " dimensions " of the painting, we arrive at

the basis for the entire theory of pictorial " construction " and of

its overcoming in pictorial

" composition,

" as explained in "On Modern Art." The " dimensions "

of the paintingare line, tonality of chiaroscuro, and color. As Klee explains:

‘’ The most

limited of the givens is the line solely a matter of measure.... The tonalities

or the values of chiaroscuro and the numerous gradations between white and

black are a question of weight.... The colors offer other characteristics, for

neither rule nor balance al low for complete mastery. I would call colors

qualities.... These three guiding ideas are like three domains encapsulated in

each other. 20 ‘’

Therefore,

line, tonality (chiaroscuro), and color are measure, weight, and quality. No

doubt this is why after the first caricatures and deformations or distortions

in the drawings and engravings, Klee gives himself over to tonalities around

1907-08: " I construct landscapes in black and white, painted on

glass." 21 The tonalities black white, lightening - darkening are

dynamical forms.

For Klee,

pictorial space is not an extension related to measure, it is an energy. It is

a space of stretchings, slidings, straddlings: not a state but a process.

Tonalities too are an energy from which the forms we have called "

energetic " take their starting point. Where then is the distinction

between what we have called " tectonic forms " and

"

energetic forms " ? It is tonality, and above all color, that for Klee

will be the true revelation of energetic forms. If there is, however, a

tectonic dynamic then it is always subject to the inflexible law of free fall.

It is thus purely " terrestrial " because the tectonic is the

terrestrial. For the painter, the tectonic dynamic must accede to a superior

form, to pure energetic form. This is where the painter moves from construction

to " composition. "

" We

would like henceforth to give it the musical name of com position " and he

adds: " In this received form, the world is not the only world possible.

" 22

There are,

thus, other " possible worlds. " These are the worlds that painting

will offer us. These are the "possible worlds" for which, with Klee,

we shall now search.

APPEARING: THE

TERRESTRIAL AND THE COSMIC

What does it

mean to speak of multiple " possible worlds " ? The " world

" is not, nor has it ever been for Klee, a world of substance, determined

once and for all and filled with beings themselves objectively determined. On

the contrary, that which is painted in the painting is the insubstantiality of

the world; it is the appearing of that which appears. An appearing that itself

does not appear.

The appearing

of that which appears is varied and multiple and it has nothing to do with the

notion of semblance that has always accompanied the thesis of the

substantiality of the world. What the painter tries to make " manifest

" is this " appearing. "

" In

this point of conjunction (of the inner and outer vision of things) are rooted

the forms created by the hand, completely distinct from the physical aspect of

the object but which—on the other hand, from the point of view of totality—do

not contradict it. " It is also a matter of " freely creating

abstract forms.... These forms achieve a new nature, the nature of the work.

"23

Earlier, Klee

had spoken of a " resonance between You (the object) and Me, transcending

all optical relation. " Is this not, again, the distinction we had proposed

between the pictorial eye and the optical eye? Is this not what Klee is

declaring in the famous phrase " art does not reproduce the visible but

makes visible " ? Is this not what Merleau-Ponty will call " the

concentration and advent to itself of the visible " ? 24

As is well

known, toward 1911 - 1912 Klee came into contact with the Blaue Reiter group;

thus with Kandinsky, Kubin, Franz Marc, and Macke among others he collaborated

on the second issue of the group's journal. 25

It is above

all with color that Klee will paint appearing, but never without construction.

It is on the occasion of a trip to Tunisia in April 1914, with two friends from

the Blaue Reiter (Moilliet and Macke), that Klee has a revelation concerning

color. He writes, in his journal, on April 16, in Kairouan:

‘’ It

penetrates so deeply and so gently into me, I feel it and it gives me

confidence in myself without effort. Color possesses me. I don't have to pursue

it. It will possess me always, I know it. That is the meaning of this happy

hour: Color and I are one. I am a painter. 26 ‘’

Also worth

mentioning are the watercolors from 1914 - 1915, such as Before the Gates of

Kairouan (vor den Toren v. Kairuan ), View of St. Germain ( Ansicht v. St.

Germain; plate 58), Garden in St. Germain, the European Quarter of Tunis (

Garten in der tune sischen Europaer Kolonie St. Germain)—all of which display

an almost Cezanne-like technique 27—or In the Kairouan Style ( im Stil v.

Kairouan ) with its more marked geometrism.

Let us return

to Klee's theoretical writings and in particular to the Bauhaus course

( Walter

Gropius invited Klee to teach, beginning in 1921, in Weimar and then in Dessau

). Having named the three characters - the linear, the tonal, and the chromatic

- and having established the terrestrial as the domain of the massive, it

becomes necessary for Klee to interrogate what he calls the " intermediary

milieu " of air and water. This interrogation of intermediary milieu

allows him to distinguish quite pertinently between " rigid rhythms "

and " unbounded rhythms. " Rigid rhythms, such as a man climbing a

staircase, a falling stone bouncing down an incline, and unbounded rhythms,

such as a rising balloon, a meteor.

Thus

pictorial " composition, " which is to hold together construction and

phenomenon, is itself the combination of rigid and unbounded rhythms. This is

how, what Klee calls a " superior polyphony " is formed, and it is

how the painting becomes a " superior organism, " a " synthesis

of dissemblances " 28 and an " organization of multiplicity in a

unity. " 29

But what does

this mean? It will suffice for us to continue the investigation of movement.

Klee picks up the analysis of the pendulum where he had left off: " Let us

free the pendulum from weight. " In giving to it a strong impetus, the

pendulum is put into a continual circular motion until it is stopped. It thus

logically describes a never-ending circle. The circle is " the purest of

dynamical forms. " 30

Circular

movement - the purest of movements - frees us from pendulum movement and from

the earth that dominated the theory of lines and of surfaces. 31 With circular

movement ( for example that of a spinning top when it encounters no obstacle or

resistance, or that of the spiral ) we penetrate into the " cosmic, "

infinite, movement freed from terrestrial weight. On the contrary, terrestrial

movements are finite movements with a beginning and an end. The analyses of the

circle and of its theoretically infinite rotation also introduce us to the

superb analyses of color that occupy two of the last Bauhaus courses ( numbers

ten and eleven, those from November 28 and December, 12, 1922 ). Here, Klee

elaborates what he calls a " topography of color " in accordance with