GERHARD RICHTER: REAL & TANGIBLE ACCOMPLISHMENTS

A

GERHARD RICHTER: REAL & TANGIBLE ACCOMPLISHMENTS

AS A YOUNG MAN

While the years immediately following the end of World

War II were in many ways difficult, Richter also has fond memories of this

time, not least because he found he had access to books that had previously

been forbidden under Nazi control. Speaking to Robert Storr, Richter explained:

"It was very nasty, [but] when the Russians came to our village and

expropriated the houses of the rich who had already left or were driven out,

they made libraries for the people out of these houses. And that was fantastic."1 In

a later conversation with Jan Thorn-Prikker, Richter elaborated, "Cesare

Lombroso's Genius and Madness, Hesse, Stefan Zweig, Feuchtwanger, all that

middle-class literature. It was a wonderful, care-free time … made it easy to

forget the dark side of things."2 Dietmar Elger, having

described Richter's mother Hildegard's role in encouraging her son's interest

in Nietzsche, Goethe, Schiller and others, notes that it was an "endless

supply of illustrated books that prompted his own first drawings."3 In

an interview with Jeanne Anne Nugent, Richter recalls studying art "from

books and from the little folios with art prints that you used to get then – I

remember Diego Velázquez, Albrecht Dürer, Lovis Corinth […] It was simply a

matter of what was around, what we saw and bought for ourselves."4

It was around this time, at the age of 15 or 16, that Gerhard's passion for art

began in earnest, having an early epiphany during an eight-week summer camp

organized by the Russian-controlled State, where "for the first time he

spent a lot of time drawing."5 One of the first drawings

that Richter recalls and acknowledges producing6 as a young man

in 1946 was a nude figure copied from a book, which his parents are said to

have reacted to with both pride and embarrassment.7 He recalls

also having made landscapes and self-portraits, and perhaps more unusually,

often working in watercolours. In a 2002 interview with Storr, Richter

describes a watercolour drawing he produced whilst living in the village of

Waltersdorf of a group of people dancing. "Automatically I was an

outsider. I couldn't speak the dialect and so on. I was at a club, watching the

others dance, and I was jealous and bitter and annoyed. So in the watercolor,

all this anger is included, at 16. It was the same with the poems I was writing

– very romantic, but bitter and nihilistic, like Nietzsche and Hermann

Hesse."8

In 1947, while still studying stenography, accounting and Russian at college in nearby Zittau, Richter began attending evening classes in painting. Little has been documented about these first painting lessons, although Elger records that before completing the course, Richter realized that he had learnt all that he was likely to from the teachers there.9 A year later, Richter moved into a hostel for apprentices in Zittau, leaving his family home in Waltersdorf.

While clearly passionate about art, on completing his studies in Zittau in 1948, Richter did not assume his career would be as a painter, and for a while considered an eclectic array of professions, including forestry, dentistry and lithography. Looking for openings that would use his artistic skills for trade and commercial purposes if not in the fine art arena, his first position was as a member of a team producing banners for the German Democratic Republic government. Storr recounts that during his five months in this post, Richter never had the opportunity to actually paint any of the banners himself, instead being charged with the task of taking the old banners and cleaning them up ready for his colleagues to paint.10 In February 1950 he was taken on as an assistant set painter for the municipal theatre in Zittau. Richter had recently been involved with an amateur theatre group11, so it was perhaps through this, or even, as Storr proposes, through friends from his evening classes, that he was aware of and disposed to the role at the theatre. During his few months here, Elger notes that he enjoyed working on the sets for productions including Goethe's Faust and Schiller's William Tell among others. His career in the theatre came to an abrupt end, however, when the young Richter refused to do wall painting work on the theatre's staircases, and was promptly dismissed.12

Soon after leaving the theatre, he applied to study painting at the Dresden Art Academy [Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden]. It is unclear whether he had already been planning to do so whilst at the theatre, or whether his dismissal prompted fresh consideration of his future. But it was clearly an idea to which he was committed, as having had his first application rejected, he was advised by the examiners to find a job with a state-run organization in order to increase his chances of being accepted, which he duly did. As Elger explains, State employees tended to receive preferential treatment at that time, and the recommendation must have worked, as following eight months working as a painter at the Dewag textile plant in Zittau, he reapplied and was accepted onto the course.13 He returned to his birth city of Dresden in the summer of 1951, ready to begin his formal studies to be a painter.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 1947, while still studying stenography, accounting and Russian at college in nearby Zittau, Richter began attending evening classes in painting. Little has been documented about these first painting lessons, although Elger records that before completing the course, Richter realized that he had learnt all that he was likely to from the teachers there.9 A year later, Richter moved into a hostel for apprentices in Zittau, leaving his family home in Waltersdorf.

While clearly passionate about art, on completing his studies in Zittau in 1948, Richter did not assume his career would be as a painter, and for a while considered an eclectic array of professions, including forestry, dentistry and lithography. Looking for openings that would use his artistic skills for trade and commercial purposes if not in the fine art arena, his first position was as a member of a team producing banners for the German Democratic Republic government. Storr recounts that during his five months in this post, Richter never had the opportunity to actually paint any of the banners himself, instead being charged with the task of taking the old banners and cleaning them up ready for his colleagues to paint.10 In February 1950 he was taken on as an assistant set painter for the municipal theatre in Zittau. Richter had recently been involved with an amateur theatre group11, so it was perhaps through this, or even, as Storr proposes, through friends from his evening classes, that he was aware of and disposed to the role at the theatre. During his few months here, Elger notes that he enjoyed working on the sets for productions including Goethe's Faust and Schiller's William Tell among others. His career in the theatre came to an abrupt end, however, when the young Richter refused to do wall painting work on the theatre's staircases, and was promptly dismissed.12

Soon after leaving the theatre, he applied to study painting at the Dresden Art Academy [Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden]. It is unclear whether he had already been planning to do so whilst at the theatre, or whether his dismissal prompted fresh consideration of his future. But it was clearly an idea to which he was committed, as having had his first application rejected, he was advised by the examiners to find a job with a state-run organization in order to increase his chances of being accepted, which he duly did. As Elger explains, State employees tended to receive preferential treatment at that time, and the recommendation must have worked, as following eight months working as a painter at the Dewag textile plant in Zittau, he reapplied and was accepted onto the course.13 He returned to his birth city of Dresden in the summer of 1951, ready to begin his formal studies to be a painter.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Cited in Storr, Forty Years of Painting,

p.20.

2 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.467.

3 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.7.

4 Interview with Jeanne Anne Nugent, 2006, Gerhard Richter: Text, p.510-11.

5 Jürgen Harten [Ed.], Gerhard Richter Bilder Paintings 1962-1985, p.9.

6 Richter does not consider the vast majority of his early works, including most of the work he went on to produce whilst a student in Dresden, to constitute part of his œuvre. When asked why during a conversation with Birgit Grimm in 2000 Richter replied, "Because I felt like I was a student until then – someone who didn't yet know what he wanted, artistically speaking." Gerhard Richter: Text, p.355

7 Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.20.

8 Interview with Richter by Robert Storr, Gerhard Richter: Text, p.375.

9 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.7.

10 Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.20. It is unclear whether this is the same job as described on p.10 of Elger's Life in Painting, which also refers to an early role preparing signs for colleagues to paint; Elger's account suggests Richter was working for a shop sign business rather than on State advertising, though Storr's account suggests he might have moved on to a second job as a sign painter.

11 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.467.

12 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.10; Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.20.

13 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.10; in Storr's account of Richter's second application to the Dresden Art School, he describes how the young artist presented a portfolio of drawings and water colours, "including a semi-abstraction that puzzled his examiners who gave it the title 'Volcano' to allay their discomfort". Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.20.

2 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.467.

3 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.7.

4 Interview with Jeanne Anne Nugent, 2006, Gerhard Richter: Text, p.510-11.

5 Jürgen Harten [Ed.], Gerhard Richter Bilder Paintings 1962-1985, p.9.

6 Richter does not consider the vast majority of his early works, including most of the work he went on to produce whilst a student in Dresden, to constitute part of his œuvre. When asked why during a conversation with Birgit Grimm in 2000 Richter replied, "Because I felt like I was a student until then – someone who didn't yet know what he wanted, artistically speaking." Gerhard Richter: Text, p.355

7 Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.20.

8 Interview with Richter by Robert Storr, Gerhard Richter: Text, p.375.

9 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.7.

10 Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.20. It is unclear whether this is the same job as described on p.10 of Elger's Life in Painting, which also refers to an early role preparing signs for colleagues to paint; Elger's account suggests Richter was working for a shop sign business rather than on State advertising, though Storr's account suggests he might have moved on to a second job as a sign painter.

11 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.467.

12 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.10; Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.20.

13 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.10; in Storr's account of Richter's second application to the Dresden Art School, he describes how the young artist presented a portfolio of drawings and water colours, "including a semi-abstraction that puzzled his examiners who gave it the title 'Volcano' to allay their discomfort". Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.20.

You may read Gerhard Richter biography under

highlighted of ‘’ Early Years ‘’, ‘’ The Dresden Years ‘’, to click above

link.

https://www.artsy.net/artist/gerhard-richter

You may visit Artsy's web page to find out more paintings and latest exclusive articles about Gerhard Richter, as well as solo & group exhibitions to click above link.

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 1991

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 cm x 200 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 747-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

BALLET DANCERS - 1966

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 160 cm x 200 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 123

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 2009

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 180 cm x 180 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 910-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

FOREST - 2005

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 197 cm x 132 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 892-4

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

WOODS 5-

2005

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 197.2 x 132.1 cm

Credit: Gift of Warren and Mitzi Eisenberg and

Leonard and Susan Feinstein

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

WOODS 2

- 2005

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 197.2 x 132.1 cm

Credit: Gift of Warren and Mitzi Eisenberg and

Leonard and Susan Feinstein

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

WOODS 6

- 2005

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 197.2 x 132.1 cm

Credit: Gift of Warren and Mitzi Eisenberg and

Leonard and Susan Feinstein

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 2009

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 180 cm x 180 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 910-1

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

SMALL CHURCH – 1965

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 50 cm x 50 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 48-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

WALL - 1994

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 240 cm x 240 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 806

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

BLATT F AUS DER EDITION: 9 OBJEKTE, 1969

Dimensions: 44.9 × 44.9 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING ( RED SCRATCHED ) - 1991

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 cm x 140 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 743-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 2000

Oil on Alu Dibond

Dimensions: 46 cm x 40 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 869-1

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING (RED) - 1991

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 cm x 140 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 743-4

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 1987

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 122 cm x 87 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 638-4

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING – 1987

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 cm x 140 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 643-3

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING – 2000

Oil on Alu Dibond

Dimensions: 46 cm x 40 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 869-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING – 1987

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 cm x 140 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 643-5

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

BLATT I AUS DER EDITION: 9 OBJEKTE, 1969

Dimensions: 44.9 × 44.9 cm

© 2016

Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 1991

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 cm x 200 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 747-4

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

MV. 232 – 2011

Lacquer on Colour Photograph

Dimensions: 10 cm x 15 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

MV. 20 – 2011

Lacquer on Colour Photograph

Dimensions: 10 cm x 15 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

MV. 203 – 2011

Lacquer on Colour Photograph

Dimensions: 10 cm x 15 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

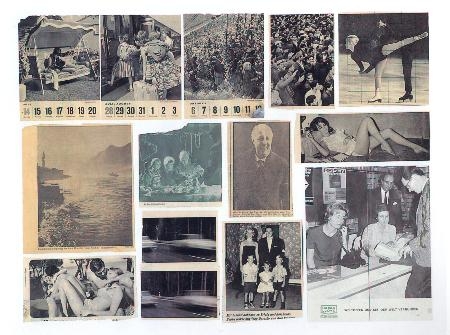

NEWSPAPER & ALBUM PHOTOS - 1962

Dimensions: 51.7 cm x 66.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 7

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

NEWSPAPER & ALBUM PHOTOS - 1962

Dimensions: 51.7 cm x 66.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 10

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

NEWSPAPER & ALBUM PHOTOS - 1962

Dimensions: 51.7 cm x 66.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 9

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

MV. 227 – 2011

Lacquer on Colour Photograph

Dimensions: 10 cm x 15 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

MV. 79 – 2011

Lacquer on Colour Photograph

Dimensions: 10 cm x 15 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

MV. 216 – 2011

Lacquer on Colour Photograph

Dimensions: 10 cm x 15 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2012

Digital Print on Paper Between Alu Dibond and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 210 cm x 230 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 927-3

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2012

Digital Print on Paper Between Alu Dibond and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 4 parts, in Total: 200 cm x 600 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 924-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2011

Digital Print on Paper Between Alu Dibond and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 220 cm x 220 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 919

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2011

Digital Print on Paper Between Alu Dibond and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 300 cm x 300 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 922-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2012

Dimensions: 3 Parts, in Total: 300 cm x 300 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 925-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2012

Digital Print on Paper Between Alu Dibond and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 110 cm x 250 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 926-3

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2012

Digital Print on Paper Between Alu Dibond and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 210 cm x 230 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 927-11

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

A

GERHARD RICHTER

1961 - 1964: THE DUSSELDORFACADEMY YEARS

On defecting to West Germany, Richter was considering moving to Munich, but made the significant decision to set up his new life in Düsseldorf following advice from Reinhard Graner, a friend already living in the city and with whom he stayed for the first few weeks.1 The city's art academy [Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf] was a hive of activity and progressive in its outlook, and despite having already completed his studies in Dresden, Richter decided to apply to study there, in part to become better informed about the current trends in the western art world, but also to find fellow artists with whom he could really engage. As a student, he was also guaranteed a stipend, which was vital for his survival during these first years in the west. Beginning his course in October 1961, he painted intensely (as he had done all summer): "I tried out everything I could".2 Starting off in the class of Ferdinand Macketanz, Richter later described his work of the time as "varying in style between Dubuffet, Giacometti, Tàpies, and many others."3 While he was unhappy with many of his paintings – and subsequently destroyed the majority of them – it was an important process of experimentation that demonstrated both his enthusiasm and commitment to his work, and certainly helped to establish his presence within the Academy.

After his first semester Richter moved into the class of Karl Otto Götz, who was attracting some of the most interesting students at the Academy. Richter had recently met fellow student Konrad Fischer [known as Konrad Lueg at that time], who also transferred into the class of Götz.4 It was to be an important association. "I was incredibly lucky to find the right friends at the Academy: Sigmar Polke, Konrad Fischer and [Blinky] Palermo."5 In addition to being a bastion of Informel painting, the Academy was soon to become a hub for Fluxus, with Joseph Beuys appointed a professor soon after Richter's arrival. The art scene extended well beyond the walls of the Academy, with a vibrant community of artists, exhibitions and events around the city and in nearby Cologne, energized not least by Group ZERO, founded by Otto Piene and Heinz Mack in 1957.

Richter's first exhibition outside the Academy was a two-person show with Manfred Kuttner at the Junge Kunst (Young Art) gallery in Fulda, a town in the centre of Germany not far from the border with the GDR.6 Richter, Lueg, Polke and Kuttner exhibited together in May 1963 at an empty shop in Düsseldorf's old town center that they rented from the local civic administration, and in October of that year, Richter and Lueg organized an exhibition and event at a furniture store in the city. Entitled Living with Pop: A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism, the initiative involved presenting a number of their paintings around the showroom along with a happening that witnessed the artists performing as living sculptures, television footage, a variety of props and homemade effigies of (the then living) John F. Kennedy and the Düsseldorf gallerist Alfred Schmela. Also featured was an installation in a cupboard by Beuys, suggesting the influence Fluxus had on Richter and his circle. "I was very impressed with Fluxus. It was so absurd and destructive," Richter has commented.7 The furniture store exhibition generated a considerable amount of interest and was characteristic of the energy, curiosity, humour and spirit shared by Richter and his peers at the time.

1961 - 1964: THE DUSSELDORFACADEMY YEARS

On defecting to West Germany, Richter was considering moving to Munich, but made the significant decision to set up his new life in Düsseldorf following advice from Reinhard Graner, a friend already living in the city and with whom he stayed for the first few weeks.1 The city's art academy [Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf] was a hive of activity and progressive in its outlook, and despite having already completed his studies in Dresden, Richter decided to apply to study there, in part to become better informed about the current trends in the western art world, but also to find fellow artists with whom he could really engage. As a student, he was also guaranteed a stipend, which was vital for his survival during these first years in the west. Beginning his course in October 1961, he painted intensely (as he had done all summer): "I tried out everything I could".2 Starting off in the class of Ferdinand Macketanz, Richter later described his work of the time as "varying in style between Dubuffet, Giacometti, Tàpies, and many others."3 While he was unhappy with many of his paintings – and subsequently destroyed the majority of them – it was an important process of experimentation that demonstrated both his enthusiasm and commitment to his work, and certainly helped to establish his presence within the Academy.

After his first semester Richter moved into the class of Karl Otto Götz, who was attracting some of the most interesting students at the Academy. Richter had recently met fellow student Konrad Fischer [known as Konrad Lueg at that time], who also transferred into the class of Götz.4 It was to be an important association. "I was incredibly lucky to find the right friends at the Academy: Sigmar Polke, Konrad Fischer and [Blinky] Palermo."5 In addition to being a bastion of Informel painting, the Academy was soon to become a hub for Fluxus, with Joseph Beuys appointed a professor soon after Richter's arrival. The art scene extended well beyond the walls of the Academy, with a vibrant community of artists, exhibitions and events around the city and in nearby Cologne, energized not least by Group ZERO, founded by Otto Piene and Heinz Mack in 1957.

Richter's first exhibition outside the Academy was a two-person show with Manfred Kuttner at the Junge Kunst (Young Art) gallery in Fulda, a town in the centre of Germany not far from the border with the GDR.6 Richter, Lueg, Polke and Kuttner exhibited together in May 1963 at an empty shop in Düsseldorf's old town center that they rented from the local civic administration, and in October of that year, Richter and Lueg organized an exhibition and event at a furniture store in the city. Entitled Living with Pop: A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism, the initiative involved presenting a number of their paintings around the showroom along with a happening that witnessed the artists performing as living sculptures, television footage, a variety of props and homemade effigies of (the then living) John F. Kennedy and the Düsseldorf gallerist Alfred Schmela. Also featured was an installation in a cupboard by Beuys, suggesting the influence Fluxus had on Richter and his circle. "I was very impressed with Fluxus. It was so absurd and destructive," Richter has commented.7 The furniture store exhibition generated a considerable amount of interest and was characteristic of the energy, curiosity, humour and spirit shared by Richter and his peers at the time.

The young men were highly competitive but also incredibly supportive of one

another, all keen to move art forward and make their names by doing so. As well

as keeping abreast of developments in Germany, they were also paying close

attention to the Pop Art movement that was coming into being across the

Atlantic, each absorbing different elements into their own thinking and

practice, and to some degree – even whilst students – making their own

contributions to the European development of the movement.

Richter's own interest in current affairs, consumer society, the media and popular culture began to manifest itself increasingly in his paintings, with early examples including Party [Catalogue Raisonné: 2-1], 1963,8depicting a male television presenter accompanied by four glamorous women during a New Year's party on a German variety show typical of the time; Table [CR: 1], 1962, based on a reproduction of a modern table published in the Italian design magazine Domus; President Johnson consoles Mrs. Kennedy [CR: 11-2], 1963, inspired by a newspaper cutting; and Folding Dryer [CR: 4], 1962, depicting an advert – replete with text – for a clothes airer from a magazine. These works were the beginning of Richter's professional œuvre and it was the use of photographic images – something that had previously been inconceivable to him and to academic painting – that marked the pivotal breakthrough.

Having found an inroad into his practice, he set about exploring the relationships between the photographic image and painting, producing some of his first works to use techniques of blurring in 1963, including Pedestrians [CR: 6] and Alster [CR: 10]. He began a series of paintings of military jets that continued into 1964, along with an increasing number of portraits, primarily in black and white, based on media images and found photographs, including some of his own family. By the time Richter left the Academy in the summer of 1964, he was already in his stride and ready to begin his career in earnest.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.472; Elger, A Life in Painting, p.32.

Richter's own interest in current affairs, consumer society, the media and popular culture began to manifest itself increasingly in his paintings, with early examples including Party [Catalogue Raisonné: 2-1], 1963,8depicting a male television presenter accompanied by four glamorous women during a New Year's party on a German variety show typical of the time; Table [CR: 1], 1962, based on a reproduction of a modern table published in the Italian design magazine Domus; President Johnson consoles Mrs. Kennedy [CR: 11-2], 1963, inspired by a newspaper cutting; and Folding Dryer [CR: 4], 1962, depicting an advert – replete with text – for a clothes airer from a magazine. These works were the beginning of Richter's professional œuvre and it was the use of photographic images – something that had previously been inconceivable to him and to academic painting – that marked the pivotal breakthrough.

Having found an inroad into his practice, he set about exploring the relationships between the photographic image and painting, producing some of his first works to use techniques of blurring in 1963, including Pedestrians [CR: 6] and Alster [CR: 10]. He began a series of paintings of military jets that continued into 1964, along with an increasing number of portraits, primarily in black and white, based on media images and found photographs, including some of his own family. By the time Richter left the Academy in the summer of 1964, he was already in his stride and ready to begin his career in earnest.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.472; Elger, A Life in Painting, p.32.

2 GR, Statement, 10 October 1973, Gerhard Richter: Text,

p.84.

3 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.472.

4 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.37.

5 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.473.

6 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.37.

7 Interview with Dorothea Dietrich, 1985. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.157.

8 Richter's catalogue raisonné is described by Elger as follows: "[In 1969 he began to devise] the first version of the catalogue raisonné, introducing the numbering system that he still uses today. Not every artwork is included. […] The catalogue raisonné is thus conceived not as an exhaustive record of everything he has painted but as a corpus of works established by the artist himself." Elger, A Life in Painting, p.169. Robert Storr asserts that the catalogue raisonné is "less a literal history of his production than an empirical narrative construct internally adjusted to account for the importance paintings had for him after he had studied them in the context of others of their generation." Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.29.

3 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.472.

4 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.37.

5 Interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker, 2004. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.473.

6 Elger, A Life in Painting, p.37.

7 Interview with Dorothea Dietrich, 1985. Gerhard Richter: Text, p.157.

8 Richter's catalogue raisonné is described by Elger as follows: "[In 1969 he began to devise] the first version of the catalogue raisonné, introducing the numbering system that he still uses today. Not every artwork is included. […] The catalogue raisonné is thus conceived not as an exhaustive record of everything he has painted but as a corpus of works established by the artist himself." Elger, A Life in Painting, p.169. Robert Storr asserts that the catalogue raisonné is "less a literal history of his production than an empirical narrative construct internally adjusted to account for the importance paintings had for him after he had studied them in the context of others of their generation." Storr, Forty Years of Painting, p.29.

You may read Gerhard Richter’s biography under

highlighted of ‘’ 1964-1970: Getting Established ’’, ‘’ The 1970s: Exploring

Abstraction ‘’, ‘’’ The 1980s: Rising to International Acclaim ‘’ to click

above link.

‘’ Pop art is

neither an American invention nor an import, yet the terms and names were

coined in the US, where they were popularised much faster than in Germany. This

kind of art has evolved organically and independently over here, yet at the

same time it becomes an analogy to American pop art due to certain

psychological, cultural and economical preconditions that are the same in

Germany as they are in the US. [...] For the first time we are showing paintings

in Germany that relate to those terms, representing pop art, junk culture,

imperial or capitalistic realism, new figuration, naturalism, German pop and

other comparable terms. ‘’

Letter

to the "Neue Deutsche Wochenschau", 29 April 1963

Gerhard Richter

ROOMS - 1970

Dimensions: 66.7 cm x 51.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 239

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ROOMS - 1971

Dimensions: 66.7 cm x 51.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 236

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

SKETCHES ( COLOUR CHARTS ) - 1966

Dimensions: 66.7 cm x 51.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 276

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

‘’ How

do you interpret your role as a painter in our society?

As a role that everyone has. I would like to try to understand what is. We know very little, and I am trying to do it by creating analogies. Almost every work of art is an analogy. When I make a representation of something, this too is an analogy to what exists; I make an effort to get a grip on the thing by depicting it. I prefer to steer clear of anything aesthetic, so as not to set obstacles in my own way and not to have the problem of people saying: 'Ah, yes, that's how he sees the world, that's his interpretation.'’

As a role that everyone has. I would like to try to understand what is. We know very little, and I am trying to do it by creating analogies. Almost every work of art is an analogy. When I make a representation of something, this too is an analogy to what exists; I make an effort to get a grip on the thing by depicting it. I prefer to steer clear of anything aesthetic, so as not to set obstacles in my own way and not to have the problem of people saying: 'Ah, yes, that's how he sees the world, that's his interpretation.'’

Interview

with Rolf-Gunter Dienst, 1970

Gerhard Richter

''

What does the word 'Informel' mean to you today?

As I see it, all of them – Tachists, Action Painters, Informel artists, and the rest – are only part of an Informel movement that covers a lot of other things as well. I think there's an Informel element in Beuys, as well; but it all began with Duchamp and chance, or with Mondrian, or with the Impressionists. The Informel is the opposite of the constructional quality of classicism – the age of kings, or clearly formed hierarchies.

So in this context you still see yourself as an Informel artist?

Yes, in principle. The age of the Informel has hardly begun yet. ''

As I see it, all of them – Tachists, Action Painters, Informel artists, and the rest – are only part of an Informel movement that covers a lot of other things as well. I think there's an Informel element in Beuys, as well; but it all began with Duchamp and chance, or with Mondrian, or with the Impressionists. The Informel is the opposite of the constructional quality of classicism – the age of kings, or clearly formed hierarchies.

So in this context you still see yourself as an Informel artist?

Yes, in principle. The age of the Informel has hardly begun yet. ''

Interview

with Hans Ulrich Obrist, 1993

Gerhard Richter

ROOMS - 1971

Dimensions: 51.7 cm x 66.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 230

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

SKETCHES ( COLOUR FIELDS ) - 1971

Dimensions: 66.7 cm x 51.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 274

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

SKETCHES ( COLOUR CHARTS ) - 1966

Dimensions: 51.7 cm x 66.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 279

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

SKETCHES ( COLOUR FIELDS ) - 1971

Dimensions: 51.7 cm x 66.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 282

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

‘’ I

blur things to make everything equally important and equally unimportant. I

blur things so that they do not look artistic or craftsman like but

technological, smooth and perfect. I blur things to make all the parts a closer

fit. Perhaps I also blur out the excess of unimportant information. ‘’

Notes,

1964-65

Gerhard Richter

‘’

Your canvases always display perfect technique…

Unlike the period when one had to learn technique and train from the youngest age, today no one masters technique any more at all. Painting has become so easy – anyone can do it! – that it's often very bad. In this context, as soon as someone knows technique, it jumps out at the viewer. That said, for me technique is something obvious: it's never a problem. I've just remained extremely attached to a culture of painting. What's much more important to me is the attempt, the desire to show what I want, in the best way possible. That's why technique is useful for me. For me, perfection is as important as the image itself. ‘’

Unlike the period when one had to learn technique and train from the youngest age, today no one masters technique any more at all. Painting has become so easy – anyone can do it! – that it's often very bad. In this context, as soon as someone knows technique, it jumps out at the viewer. That said, for me technique is something obvious: it's never a problem. I've just remained extremely attached to a culture of painting. What's much more important to me is the attempt, the desire to show what I want, in the best way possible. That's why technique is useful for me. For me, perfection is as important as the image itself. ‘’

Conversation

with Henri-François Debailleux, 1993

Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 1991

Oil on Canvas

200 cm x 180 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 745-1

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

A

A

ABSTRACT PAINTING – 1978

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 28 cm x 40 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 432-7

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

WHITE - 2006

Dimensions: 30 cm x 44 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 899-4

Oil on Alu Dibond

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 1997

Oil on Alu Dibond

Dimensions: 55 cm x 48 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 843-8

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING (809-3) - 1994

Oil Paint on Canvas

Dimensions Support: 2300 x 2048 x 75 mm

Collection: Tate / National Galleries of Scotland

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 1995

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 92 cm x 82 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 828-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

SNOW WHITE (15.11.05) - 2005

Acrylic and Graphite on Offset Print

Dimensions: 22.5 cm x 32 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

RIVER – 1995

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 cm x 320 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 823

©

Gerhard Richter

FOR 48 PORTRAIT - 1971

Dimensions: 66.7 cm x 51.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 30

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

FOR 48 PORTRAIT - 1971

Dimensions: 66.7 cm x 51.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 34

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

FOR 48 PORTRAIT - 1971

Dimensions: 66.7 cm x 51.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 31

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

23.2.91 - 1991

Colored Ink and Watercolor on Paper With Pencil on

Board

Dimensions: 24.2 x 33.5 cm

Credit: Gift of The Patsy R. Taylor Family Trust

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

2.11.1989 - 1989

Graphite on Paper

Dimensions: 21 cm x 29.7 cm

Drawings CR: 89/5

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 2004

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 cm x 200 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 889-13

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

NEWSPAPER & ALBUM PHOTOS – 1963

Dimensions: 51.7 cm x 66.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 11

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

NEWSPAPER & ALBUM PHOTOS - 1962

Dimensions: 51.7 cm x 66.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 8

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

NEWSPAPER & ALBUM PHOTOS – 1963

Dimensions: 51.7 cm x 66.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 12

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 2009

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 60 cm x 50 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 908-7

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 2005

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 30 cm x 44 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 894-1

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

7.24.94 - 1994

Oil on Paper

Dimensions: 21 x 29.8 cm

Credit: The Judith Rothschild Foundation

Contemporary Drawings Collection Gift

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING – 2005

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 30 cm x 44 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 894-5

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

FLOW ( 933-3 ) - 2013

Lack Hinter Glas, Auf Alu-Dibond Montiert, 100 x 200 cm

© Gerhard Richter, Köln 2013

Lack Hinter Glas, Auf Alu-Dibond Montiert, 100 x 200 cm

© Gerhard Richter, Köln 2013

ABSTRACT PAINTING – 1991

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 112 cm x 102 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 748-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

EMA (NUDE ON A STAIRCASE) - 1966

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 cm x 130 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 134

CATHEDRAL SQUARE, MILAN - 1968

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 275 cm x 290 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 169

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

SKULL WITH CANDLE - 1983

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 100 cm x 150 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 547-2

ABSTRACT PAINTING – 1979

Oil Paint on Canvas

Dimensions: 90 cm x 95 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 449-2

BIRKENAU 2014

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 260 x 200 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 937-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

TRI-STAR (BUTIN 57) - 1981

Lacquer on Record

Dimensions: 17.5 cm diameter

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 2001

Oil on Aluminium

Dimensions: 57 cm x 52 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 875-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

WHITE - 2006

Oil on Paper

Dimensions: 120 cm x 89 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 898-9

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 1978

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 33 cm x 27 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 432-1

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 2000

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 147 cm x 102 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 868-6

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

VERKUNDIGUNG NACH TIZIAN, 1973

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 125 × 200 cm

© 2014 Gerhard Richter

MV. 18 - 2011

Lacquer on Colour Photograph

Dimensions: 10 cm x 15 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STAMMHEIM - 1994

Oil on Printed Paper

Dimensions: 19 cm x 11.6 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STAMMHEIM - 1994

Oil on Printed Paper

Dimensions: 19 cm x 11.6 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

MV.12, 2011

Lacquer on Color Photograph

Dimensions: 10.2 × 15.2 cm

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

GILBERT & GEORGE - 1975

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 125 cm x 150 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 383

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

ABSTRACT PAINTING - 2004

Oil on Alu Dibond

Dimensions: 70 cm x 60 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 889-1

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

FOR 48 PORTRAIT - 1971

Dimensions: 66.7 cm x 51.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 35

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

FOR 48 PORTRAIT - 1971

Dimensions: 66.7 cm x 51.7 cm

Atlas Sheet: 36

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2012

Digital Print on Paper Between Aluminium and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 150 cm x 300 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 926-7

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2011

Digital Print on Paper Between Aluminium and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 160 cm x 300 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 920-6

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2012

Digital Print on Paper Between Alu Dibond and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 120 cm x 300 cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 926-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

STRIP - 2011

Digital Print on Paper Between Aluminium and Perspex

(Diasec)

Dimensions: 2 Parts, in Total: 200 cm x 440

cm

Catalogue Raisonné: 921-2

© 2016 Gerhard Richter

GERHARD

RICHTER

THE

1990’S: CONSOLIDATION & EVOLUTION

As the

1990s began, Richter was busy with his Abstract Paintings, to which he

dedicated himself almost exclusively for the first year. After a hectic couple

of years in terms of his exhibitions schedule and increasing demands from the

art world, he was keen to try to keep things manageable, postponing several

exhibitions to which he had been committed.1 Richter's

consistently formidable productivity and prolific output can often mask the

sheer volume of administration, travel and communication needed to maintain a

top-flight career in the art world, not to mention the need for space to think

and to develop new ideas.

In 1991 he returned to the medium of mirrors, which he had first explored a decade earlier in four pieces [CR: 470/1-2, 485/1-2]. These had developed out of the glass works first executed back in 1967 [4 Panes of Glass, CR: 160] and in 1977 [Pane of Glass, CR: 415/1-2 and Double Pane of Glass, CR: 416]. A private commission in 1989, which had seen Richter bring together his colour chart works with his interest in glass, resulted in a sizeable domestic stained glass window made up of many squares of colours [Glass Window, 625 Colours, CR: 703]. The combination of glass, mirror and colour was something that still offered fertile terrain for Richter to exploit, and the works of 1991 provided an opportunity to present the culmination of his thinking about minimalist abstraction. According to the catalogue raisonné, three rectangular works entitled Mirror, Grey [CR: 735/1-3] were produced first, using glass coated with grey pigment. The grey works were immediately followed by eight works entitled Mirror, Blood Red [CR: 736/1-8] and then by two pairs intended to be sited in the corner of a room: Corner Mirror, Brown-Blue [CR: 737-1] and Corner Mirror, Green-Red [CR: 737-2]. Almost 20 more grey mirrors then followed before the end of 1992.

In 1991 he returned to the medium of mirrors, which he had first explored a decade earlier in four pieces [CR: 470/1-2, 485/1-2]. These had developed out of the glass works first executed back in 1967 [4 Panes of Glass, CR: 160] and in 1977 [Pane of Glass, CR: 415/1-2 and Double Pane of Glass, CR: 416]. A private commission in 1989, which had seen Richter bring together his colour chart works with his interest in glass, resulted in a sizeable domestic stained glass window made up of many squares of colours [Glass Window, 625 Colours, CR: 703]. The combination of glass, mirror and colour was something that still offered fertile terrain for Richter to exploit, and the works of 1991 provided an opportunity to present the culmination of his thinking about minimalist abstraction. According to the catalogue raisonné, three rectangular works entitled Mirror, Grey [CR: 735/1-3] were produced first, using glass coated with grey pigment. The grey works were immediately followed by eight works entitled Mirror, Blood Red [CR: 736/1-8] and then by two pairs intended to be sited in the corner of a room: Corner Mirror, Brown-Blue [CR: 737-1] and Corner Mirror, Green-Red [CR: 737-2]. Almost 20 more grey mirrors then followed before the end of 1992.

In his

Abstract Paintings of 1992, stripes and grids were to dominate. Dozens of

related canvases produced in a relatively short period of time suggested that

Richter was experimenting but looking for something specific. What he was

looking for he had touched upon at various points throughout his career, but as

is often the case with Richter, his painterly research often results in things

that only come to make sense to him much later on, at which point he takes them

up again in order to develop them.2 Several

Abstract Paintings of 1987 such as CR: 621 and CR:

643/1-5 had sown the seeds for what Richter was striving for in

1992, in which horizontal and vertical striations could be unified within the

complex dimensional planes of an abstract composition and the flatbed picture

plane. The challenge equally seemed to involve unifying bright colours with the

more muted, melancholy palette to which Richter is periodically drawn. It was a

subject he had addressed back in 1972 with his Red-Blue-Yellow works

[CR: 327-339] in which he had investigated the processes and

stages of the muddying of primary colours through the mixing of paint. Coming

back to this topic with the experience of over twenty years of abstract

painting now under his belt, Richter's first significant works to really

synthesise these elements in this way was a cycle of four paintings he

titled Bach [CR:

785-788], 1992. Each canvas was three by three metres and while he

had worked on even larger canvases in the past, these were in many ways the new

benchmark for Richter's Abstract Paintings, paving the way for future major

cycles, and in particular, the Cage paintings

[CR: 897/1-6] of 2006, alongside which they were displayed at

the Museum Ludwig in Cologne in 2008.

Apart from being the year of another major touring retrospective exhibition, this time starting with the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1993 was a year in which Richter's private world was undergoing considerable change once again. His marriage to Isa Genzken was coming to an end. A sequence of paintings from that year in which she posed for Richter as a model as if in a life-drawing class are strangely bleak and detached, suggesting the emotional distance that had grown between them [CR: 790/1-5]. A year later, Richter met the artist Sabine Moritz, fell in love with her and settled down for good. The warmth and affection he has for Sabine Moritz was immediately apparent in two of just a handful of photo-paintings Richter made in 1994, both entitled Reader [CR: 799-1, 804]. With a charm and joyfulness comparable to his painting Betty of 1988, the paintings depict Sabine Moritz in profile, illuminated from behind, reading a German magazine. A series of eight paintings from 1995 of Sabine Moritz with newborn baby son Moritz [CR: 827/1-8] are among the most intimate and personal of Richter's oeuvre, described by Storr as having "an almost palpable tenderness"3 and by Elger as depicting "domestic bliss".4 With daughter Ella Maria born a year after Moritz, in the summer of 1996 the family moved into their newly built home in Hahnwald in the south of Cologne.5

Apart from being the year of another major touring retrospective exhibition, this time starting with the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1993 was a year in which Richter's private world was undergoing considerable change once again. His marriage to Isa Genzken was coming to an end. A sequence of paintings from that year in which she posed for Richter as a model as if in a life-drawing class are strangely bleak and detached, suggesting the emotional distance that had grown between them [CR: 790/1-5]. A year later, Richter met the artist Sabine Moritz, fell in love with her and settled down for good. The warmth and affection he has for Sabine Moritz was immediately apparent in two of just a handful of photo-paintings Richter made in 1994, both entitled Reader [CR: 799-1, 804]. With a charm and joyfulness comparable to his painting Betty of 1988, the paintings depict Sabine Moritz in profile, illuminated from behind, reading a German magazine. A series of eight paintings from 1995 of Sabine Moritz with newborn baby son Moritz [CR: 827/1-8] are among the most intimate and personal of Richter's oeuvre, described by Storr as having "an almost palpable tenderness"3 and by Elger as depicting "domestic bliss".4 With daughter Ella Maria born a year after Moritz, in the summer of 1996 the family moved into their newly built home in Hahnwald in the south of Cologne.5

Richter

continued primarily producing abstract works interspersed with the occasional

photo painting throughout the late 1990s. Speaking about this in 1999, Richter

commented, "I love figurative painting and find it very interesting. I've

not done a lot of figurative work because I lack subjects. Abstract is

something everyday for me, as natural as walking or breathing".6 Photo-painting highlights

of the last years of the decade included the site at Hahnwald on which their

house had been built [Hahnwald, CR: 840-1], 1997, Orchid [CR: 848-9], Seascape [CR:

852-1], 1998, and Summer Day [CR: 859-1], 1999. Richter's output

during this time was lower than usual due to the artist having suffered a

stroke in late summer of 1998, from which he made a swift recovery.7

Since at least as early as 1986, Richter had been developing another medium within his practice, namely painting over the top of photographs. The earliest recorded is Untitled 23.3.86, 1986. From looking at this and the subsequent image, it would be difficult to discern that there was a photographic image buried beneath the otherwise abstract oil painting, but this was soon to change with Untitled Toronto from 1987, in which the photographed cityscape was left clearly visible. He has since produced in excess of 700 Overpainted

Since at least as early as 1986, Richter had been developing another medium within his practice, namely painting over the top of photographs. The earliest recorded is Untitled 23.3.86, 1986. From looking at this and the subsequent image, it would be difficult to discern that there was a photographic image buried beneath the otherwise abstract oil painting, but this was soon to change with Untitled Toronto from 1987, in which the photographed cityscape was left clearly visible. He has since produced in excess of 700 Overpainted

Photographs,

including a substantial series produced in 2000 entitled Firenze,

which consisted of 100 parts. These works offer another way for Richter to

negotiate the languages of figuration, abstraction and the photograph, often

with considerable impact and striking effect.

One

significant commission at the end of the millennium came from the German

government, which was in the process of commissioning works by a number of

German artists for its new buildings in Berlin. Richter and Polke were invited

to devise works for the entrance hall of the Reichstag building. Elger's

account documents Richter's original hope to address the subject of the

Holocaust with this commission, but the artist eventually decided that

something more apolitical would be more appropriate, opting to make a work

based on the German national colours of black, red and gold.8 The final work [Black,

Red and Gold, CR: 856, 1999], took the form of six large, thin

rectangular glass panels, coloured with black, red and gold enamel. Two black

panels were on the top, two red panels were in the middle, and two gold panels

were at the bottom, as if the flag in the format of a long vertical strip. The

combined length of the panels was over 20 metres. A natural evolution of his

mirror works with which he had begun the decade, this simple concept was a

perfect response to both the commission and its architectural context.

GERHARD RICHTER IN THE 21 ST CENTURY: REAL & TANGIBLE ACCOMPLISHMENTS

"Well, after this century of grand proclamations and terrible illusions, I hope for an era in which real and tangible accomplishments, and not grand proclamations, are the only things that count."

At the turn of the millennium, Richter was increasingly focussed on his Abstract Paintings, with three paintings of his young son Moritz [ CR: 863/1-3 ] notable exceptions to this trend. Transparency, translucency, opacity and reflection were still clearly subjects with which the artist was engaging at this time, almost a decade since his last concerted period to have addressed them. Eight Grey [CR: 874/1-8] in 2001 heralded a number of works the following year that brought glass to centre stage. Works such as Pane of Glass [ CR: 876-1 ], 4 Standing Panes [ CR: 877-1 ] and 7 Standing Panes [ CR: 879-1 ] demonstrated an interest in pushing wall-based works into the realm of the sculptural.

2002 was also a significant year for Richter due to his major retrospective exhibition Forty Years of Painting at MoMA in New York. Curated by Robert Storr, the exhibition featured 190 works, and accompanied by a seminal catalogue, was one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of Richter's works of his career. It was also the exhibition that confirmed Richter's status as one of the leading artists in the world, and was described by Storr in his introduction as "long overdue" in the United States.2

In 2003 Richter embarked on a small but substantially sized series of paintings entitled Silicate [ CR: 885/1-4 ] inspired by an article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from 12 March 2003 about the shimmering qualities of certain insects' bodies.3 The resulting four large paintings are perhaps the most overtly biological of the abstract works in Richter's oeuvre, suggestive of cell formations and genetic sequences seen under the microscope.

Richter's next significant – and in some ways unexpected – departure came in the form of a single work depicting the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York of September 11, 2001, entitled simply September [ CR: 891-5 ], 2005. In a 2010 publication about the painting written by Robert Storr, the author asks: "what is the meaning of a single, small, almost abstract depiction of one of the most consequential occurrences in recent world history?

At the turn of the millennium, Richter was increasingly focussed on his Abstract Paintings, with three paintings of his young son Moritz [ CR: 863/1-3 ] notable exceptions to this trend. Transparency, translucency, opacity and reflection were still clearly subjects with which the artist was engaging at this time, almost a decade since his last concerted period to have addressed them. Eight Grey [CR: 874/1-8] in 2001 heralded a number of works the following year that brought glass to centre stage. Works such as Pane of Glass [ CR: 876-1 ], 4 Standing Panes [ CR: 877-1 ] and 7 Standing Panes [ CR: 879-1 ] demonstrated an interest in pushing wall-based works into the realm of the sculptural.

2002 was also a significant year for Richter due to his major retrospective exhibition Forty Years of Painting at MoMA in New York. Curated by Robert Storr, the exhibition featured 190 works, and accompanied by a seminal catalogue, was one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of Richter's works of his career. It was also the exhibition that confirmed Richter's status as one of the leading artists in the world, and was described by Storr in his introduction as "long overdue" in the United States.2

In 2003 Richter embarked on a small but substantially sized series of paintings entitled Silicate [ CR: 885/1-4 ] inspired by an article in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from 12 March 2003 about the shimmering qualities of certain insects' bodies.3 The resulting four large paintings are perhaps the most overtly biological of the abstract works in Richter's oeuvre, suggestive of cell formations and genetic sequences seen under the microscope.

Richter's next significant – and in some ways unexpected – departure came in the form of a single work depicting the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York of September 11, 2001, entitled simply September [ CR: 891-5 ], 2005. In a 2010 publication about the painting written by Robert Storr, the author asks: "what is the meaning of a single, small, almost abstract depiction of one of the most consequential occurrences in recent world history?

"4 Depicting the explosion of United Airlines Flight 175 as it hit the South Tower, Storr's essay describes how Richter's painting raises and encapsulates many of the complex geo - political issues that the attacks provoked, as well as the horrendous realities of those whose lives were taken away or affected by them. The painting, whilst it carries an overwhelming sense of the enormity and significance of the event, avoids spectacularizing it, instead evoking an existential numbness, sadness and incomprehension. Described by critic Bryan Appleyard for The Sunday Times as " the closest you will get to a great 9/11 work " he goes on to assert that " It reclaims the day, leaving it exactly where it was, exactly when it happened. "5

The following year, 2006, saw the creation of one of Richter's most significant cycles of Abstract Paintings, Cage [ CR: 897/1-6 ]. These six, large-scale canvases, described by Sir Nicholas Serota as " magisterial "6 were named after the American avant-garde composer John Cage, whom Richter had never personally met but whose work had long held a resonance with his own. In a conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist – one of the leading interlocutors of Richter's work since the 1990s – Richter said that he had been listening to the music of Cage whilst working in his studio at the time.7 In an interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker in 2004, Richter stated, " That's roughly how Cage put it: 'I have nothing to say and I am saying it.' I have always thought that was a wonderful quote. It's the best chance we have to be able to keep on going. "8 The concluding line in Robert Storr's 2009 publication devoted to the series, Cage – Six Paintings by Gerhard Richter, references the Cage quote, stating: "In his own idiom, and for his own reasons, [ the Cage paintings ] are Richter's beautiful way of saying nothing, and as such, of once more declaring his uncompromising independence. "9 Having been shown alongside the Bach paintings at the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, in 2008, the Cage paintings have since been exhibited at Tate Modern, London.

In 2007 Richter completed arguably his largest commission – a major stained glass window for Cologne Cathedral to replace a window that had been destroyed during World War II. He had been invited to undertake the commission back in 2002 and had devoted considerable time to developing and completing the project in the following five years. In notes prepared for a conference in July 2006, Richter wrote:

The following year, 2006, saw the creation of one of Richter's most significant cycles of Abstract Paintings, Cage [ CR: 897/1-6 ]. These six, large-scale canvases, described by Sir Nicholas Serota as " magisterial "6 were named after the American avant-garde composer John Cage, whom Richter had never personally met but whose work had long held a resonance with his own. In a conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist – one of the leading interlocutors of Richter's work since the 1990s – Richter said that he had been listening to the music of Cage whilst working in his studio at the time.7 In an interview with Jan Thorn-Prikker in 2004, Richter stated, " That's roughly how Cage put it: 'I have nothing to say and I am saying it.' I have always thought that was a wonderful quote. It's the best chance we have to be able to keep on going. "8 The concluding line in Robert Storr's 2009 publication devoted to the series, Cage – Six Paintings by Gerhard Richter, references the Cage quote, stating: "In his own idiom, and for his own reasons, [ the Cage paintings ] are Richter's beautiful way of saying nothing, and as such, of once more declaring his uncompromising independence. "9 Having been shown alongside the Bach paintings at the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, in 2008, the Cage paintings have since been exhibited at Tate Modern, London.

In 2007 Richter completed arguably his largest commission – a major stained glass window for Cologne Cathedral to replace a window that had been destroyed during World War II. He had been invited to undertake the commission back in 2002 and had devoted considerable time to developing and completing the project in the following five years. In notes prepared for a conference in July 2006, Richter wrote:

In early 2002, the master builder of the cathedral suggested that I develop a glass design for the southern window. The guiding principle was the representation of six martyrs, in keeping with the period. I was, of course, very touched to have such an honour bestowed upon me, but I soon realised I wasn't at all qualified for the task. After several unsuccessful attempts to get to grips with the subject, and prepared to finally concede failure, I happened upon a large representation of my painting with 4096 colours. I put the template for the design of the window over it and saw that this was the only possibility.10

Several months later, Richter began work on a model with test patterns and a number of design concepts. He settled on a design in which 11,000 mouth-blown squares measuring 94 x 94 millimetres each were to be used, with half of these selected randomly by a computer programme, and the other half a mirror image of these. As well as an evolution of his Colour Charts and Colour works of the 1960s and 70s, the Cologne Cathedral Window [ CR: 900 ] was also informed by his Glass Window, 625 Colours [ CR: 703 ] of 1989. The resulting window is a remarkable accomplishment, both real and tangible, and has been documented extensively in a film by Corinna Belz released in 2007.11

In 2008, Richter embarked on a significant body of colourful abstract work entitled Sinbad [ CR: 905 ]. Comprising 100 small paintings in enamel on the back of glass, Sinbad is the first series of works by Richter to allude to The Book of One Thousand and One Nights ( Arabian Nights ) and was followed in 2010 by Aladdin [ CR: 913 ]. That the artist was clearly thinking a lot about the Middle East is illustrated by the related series Baghdad [ CR: 914 ], 2010 and Abdallah [ CR: 917 ], 2010. Taking up some of the brighter palettes he had explored in the abstract works of the late 1970s and early 1980s, Sinbad is a rich, joyous journey through colour and abstraction.

One of Richter's most recent new avenues for the exploration of abstraction and colour takes the form of stripes. A work entitled Strip [ CR: 920 ], 2011, consisting of a digital print on paper mounted between aluminium and Perspex, presents dozens of long horizontal stripes of varying thickness spanning a width of three metres. It is a tantalising taste of what is still to come from one of the world's most prolific and respected living artists, whose insatiable desire to explore the languages and possibilities of painting and image-making continues to keep him at the forefront of developments in contemporary art today. To coincide with Richter's 80th birthday, in October 2011 a major retrospective entitled Gerhard Richter: Panorama opened at Tate Modern, London, before touring to the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, and the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in 2012.

Prepared for www.gerhard-richter.com by Matt Price with assistance from Carina Krause, 2010-11. The text would not have been possible without the scholarship and guidance of Dietmar Elger.

In 2008, Richter embarked on a significant body of colourful abstract work entitled Sinbad [ CR: 905 ]. Comprising 100 small paintings in enamel on the back of glass, Sinbad is the first series of works by Richter to allude to The Book of One Thousand and One Nights ( Arabian Nights ) and was followed in 2010 by Aladdin [ CR: 913 ]. That the artist was clearly thinking a lot about the Middle East is illustrated by the related series Baghdad [ CR: 914 ], 2010 and Abdallah [ CR: 917 ], 2010. Taking up some of the brighter palettes he had explored in the abstract works of the late 1970s and early 1980s, Sinbad is a rich, joyous journey through colour and abstraction.

One of Richter's most recent new avenues for the exploration of abstraction and colour takes the form of stripes. A work entitled Strip [ CR: 920 ], 2011, consisting of a digital print on paper mounted between aluminium and Perspex, presents dozens of long horizontal stripes of varying thickness spanning a width of three metres. It is a tantalising taste of what is still to come from one of the world's most prolific and respected living artists, whose insatiable desire to explore the languages and possibilities of painting and image-making continues to keep him at the forefront of developments in contemporary art today. To coincide with Richter's 80th birthday, in October 2011 a major retrospective entitled Gerhard Richter: Panorama opened at Tate Modern, London, before touring to the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, and the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in 2012.

Prepared for www.gerhard-richter.com by Matt Price with assistance from Carina Krause, 2010-11. The text would not have been possible without the scholarship and guidance of Dietmar Elger.