TRACEY EMIN: I FOLLOWED YOU TO THE END AT WHITE CUBE BERMONDSEY

September 19, 2024 – November 10, 2024

TRACEY EMIN: I FOLLOWED

YOU TO THE END AT WHITE CUBE BERMONDSEY

September 19, 2024 –

November 10, 2024

Tracey Emin returns to

White Cube Bermondsey with her solo exhibition, ‘I followed you to the end’, a

presentation of new paintings and sculptures that journey through love and

loss, mortality and rebirth. Drawing from a recent, transformative experience,

Emin continues her exploration of life’s most profound and intimate moments,

with renewed intensity.

The exhibition celebrates

Emin’s expressive painterly vocabulary, focusing on the medium that has

occupied and engaged the artist in recent years. Deft, impulsive strokes

capture figures in the throes of becoming, while a palette of carmine, ivory,

deep blues and black temper the volatility of physical and emotional states

with intervals of contemplation and stillness. Serving as a fulcrum for the

exhibition’s psychical journey, the titular painting I Followed you to the

end (2024) elicits the plaintive anguish wrought from the complexities of

love. Bathed in a tempest of red and black, the outline of a solitary female

figure is framed by a handwritten exhortation to the lovers that have

mistreated her: ‘You made me like this. All of you – you – you men that I so

insanely loved so much. You are the ones that made me feel so alone. All of you

– each of you in your individual way. I – I – I – was at fault to keep loving

you. Like a fool I followed love to the end. Like the sad haunted soul that I

am, I followed you to the end’.

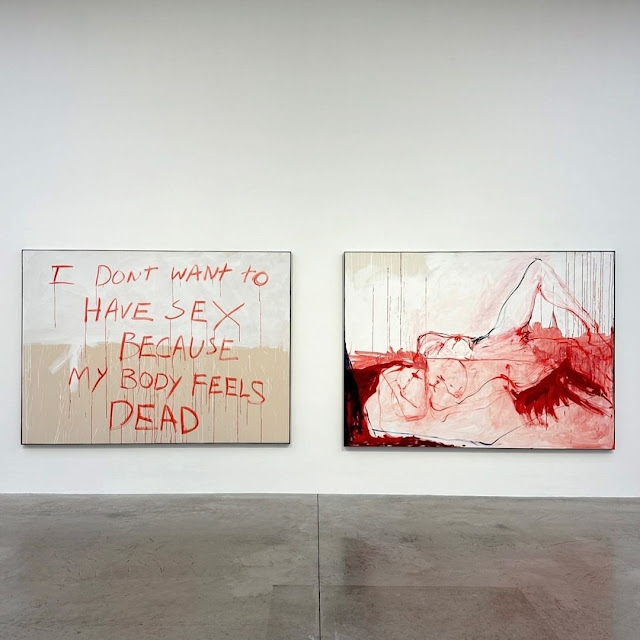

From this wounded indictment, tensions emerge in other works, where the

mourning of lost love is countered by a visceral drive for self-preservation.

In the diptych My Dead Body – A Trace of Life (2024), the female subject lies

supine, her pelvis thrust upward while her head founders beneath a crimson

tide. This horizon line extends to the second canvas, where a passage avows: ‘I

don’t want to have sex because my body feels dead’. Informed, in no small

measure, by the artist’s recent confrontation with life-threatening illness,

the work also speaks frankly of Emin’s personal reckoning with mortality. The

private spaces that Emin’s subjects inhabit – beds and baths – transform into

sepulchral vessels, securing the figure within. In I Kept

Crying (2024), the figure, shrouded in a cascade of red paint, reclines in

a bath that might also be read as a burial ground, with the taps transfiguring

into crucifixes. Elsewhere, allusions to Charon, the ferryman of the Greek

underworld, emerge in the red sails of Time to Go (2024) – a motif

that, like many others, surfaced from the subconscious during the creative act.

In several of the works, the veil between life and death is thin and permeable,

a diaphanous threshold through which the artist’s figures appear to make

contact with the Beyond. Likewise, Emin’s instinctive process involves veiling

and unveiling: she often paints an image on canvas only to obscure it later

with additional layers of white, leaving behind a spectral impression of the

over writ form, as can be seen in Take me to Heaven (2024). Here, the

subject assumes a tranquil repose, as if drifting into another realm. To the

left, a pale lavender presence – conjured through this technique – appears

beside the protagonist, serving as a proxy for the artist’s deceased mother.

Depicted within a room adorned with blue floral-patterned wallpaper, the

serenity of the scene is abruptly ruptured by a violent gush of red from the

subject’s torso, wrenching the transcendent moment back to the immediacy of the

present.

Similar decorative motifs appear in works such as The End of

Love, More Dreaming and Our World (all 2024), which draw

inspiration from the intricate designs of Turkish rugs collected by the artist,

who is of Turkish heritage herself. This patterning represents a different form

of mark-making, one led by a meditative impulse as opposed to the frenetic and

urgent fervour that often characterises her paintings. Influenced by the

evocative interior domestic scenes of Edvard Munch, the settings within these

compositions become as integral to the narrative as the figures themselves.

Autobiographical markers are woven throughout, as in The

Bridge (2024), where an undulating landscape – insinuated by the

silhouette of a sofa – symbolically connects the artist’s two hometowns of

Margate and London, with the sofa posts evoking the structural supports of the

Medway Bridge. Throughout the exhibition, the artist’s faithful familiars – her

cats – reappear across both the large canvases and small-scale paintings,

either gathered around the solitary figure or standing as stoic sentinels,

silently keeping watch. In The End of Love, they serve as surrogate

subjects, filling the void left by the stained silhouette of the two lovers,

now erased and absent from the bed.

Emin approaches her paintings without preliminary sketches or a predetermined

vision, engaging with the canvas as though it were a medium of divination,

coaxing hidden truths to the surface through the process of painting. The

images that emerge function as an interface, to resurrect former versions of

the self; to revisit defining events from her life; to weave together the

spectrum of her experience into an ever-present moment. A recurring motif in

Emin’s recent work is intimately tied to the artist’s bodily reality. Following

a diagnosis of aggressive bladder cancer in 2020, Emin underwent major surgery

to remove the affected organ and a substantial portion of the surrounding

abdominal organs. During the procedure, her ureters were rerouted to a

surgically constructed passage in her abdomen. A candid video, filmed by the

artist herself and displayed in the gallery’s auditorium, reveals in vivid

detail the stoma she now lives with – a pulsing, sunset-red orifice that may be

variously identified in the surgent valves, halos and potent reds that

punctuate Emin’s paintings.

Though painting has become increasingly central to Emin’s practice in recent

years, she has continued to create sculpture, as evidenced by the two new

bronze works featured in this exhibition. The smaller

counterpart, Ascension (2024), presents a female torso in repose and

echoes the figure depicted in My Dead Body – A Trace of Life, although

mounted on the wall in a manner reminiscent of a crucifixion. The monumental

sculpture, I Followed You To The End (2024), commands the central

space of the South Galleries. At first glance, its form appears abstract, with

textured ridges and dimpled impressions suggestive of a rugged landscape.

Navigating around and drawing back from the work, the lower anatomy of a figure

reveals itself, with sprawled legs ambiguously parted as tender invitation or

brutal subjugation. With its deeply worked surfaces directly capturing the

imprints from moulding by the artist’s hand, the sculpture evokes a sensuous

intimacy that belies its vast scale.

I FOLLOWED

YOU TO THE END, 2024

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

182.2 x 120.1 cm | 71 3/4 x 47 5/16 in.

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights

Reserved, DACS 2024.

I FOLLOWED

YOU TO THE END, 2024

Patinated

Bronze

Edition 1 of

3

Dimensions:

690 x 393 x 260 cm | 271 5/8 x 154 3/4 x 102 3/8 in.

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024.

TAKE ME TO HEAVEN, 2024

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

203.1 x 280.3 cm | 79 15/16 x 110 3/8 in.

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024.

ANOTHER PLACE

TO LIVE, 2024

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

203.1 x 280.3 cm | 79 15/16 x 110 3/8 in.

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024.

NOT FUCKABLE, 2024

Acrylic on

Canvas

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024.

I DID NOTHING WRONG, 2024

ASCENSION,

2024

Patinated

Bronze

Edition 1 of

3

Dimensions:

72.5 x 36 x 23.5 cm | 28 9/16 x 14 3/16 x 9 1/4 in.

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024.

MORE LOVE

THAN I CAN REMEMBER, 2024

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

182 x 214.2 cm | 71 5/8 x 84 5/16 in.

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights

Reserved, DACS 2024.

BLOOD – BLOOD

AND MORE BLOOD, 2024

Acrylic on

Canvas

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024.

THE END OF

LOVE, 2024

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

202.9 x 280.2 cm | 79 7/8 x 110 5/16 in.

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024.

I KEPT

CRYING, 2024

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

122.3 x 122.3 cm | 48 1/8 x 48 1/8 in.

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights Reserved,

DACS 2024.

I WAITED SO

LONG – TOO LONG, 2024

Acrylic on

Canvas

Dimensions:

152.2 x 152.2 cm | 59 15/16 x 59 15/16 in.

Image Credit: © Tracey Emin. All Rights

Reserved, DACS 2024.

ABOUT TRACEY EMIN

Tracey Emin looks to her

life for her primary material. With soul-searching candour, she probes the

construct of the self but also the very impulse to create. Unfiltered,

irreverent, raw, she draws on the fundamental themes of love, desire, loss and

grief in works that are disarmingly and unashamedly emotional. ‘The most

beautiful thing is honesty, even if it’s really painful to look at’, she has

remarked.

Self-portraiture and the

nude run throughout her practice, which Emin has described as being about

‘rites of passage, of time and age, and the simple realisation that we are

always alone’. Her earliest works refer to her family, childhood and chaotic

teenage years, growing up in the seaside town of Margate and leaving home at

the age of fifteen. What happened next is explored, in a manner that is neither

tragic nor sentimental, in drawing, painting, film, photography, sewn appliqué,

sculpture, neon and writing, as the vicissitudes of relationships, pregnancies

and abortions intersect with her commitment to the formal disciplines of art.

Most recently, the artist has experienced her body as a battleground, through

illness and ageing, on which she reports with characteristic fearlessness.

The playful title of Emin’s first solo exhibition, My Major

Retrospective 1963–1993, suggests the artist felt, despite being at the

beginning of her career, significant things had already happened. Her obsessive

assemblage of personal memorabilia included tiny photographs of her art school

paintings that she’d destroyed, a ‘photographic graveyard’ that revealed an

admiration for paintings by Egon Schiele and Edvard Munch. She details this

‘emotional suiside’ in Tracey Emin’s CV Cunt Vernacular (1997), among

several early video works that give further insight into her formation as an

artist, highlighting moments of epiphany through the use of first-person

narrative. ‘I realised there was the essence of creativity, that moment of

conception,’ she says in How It Feels (1996), a pivotal film in which

she tells the story of her abortion. ‘The whole being of everything… it had to

be about where it was really coming from’. Speaking to camera while walking

through the streets of London, she concludes that conceptual art, as an act of

reproduction, is inseparable from the artist’s inner life. Developing this

connection, the haunting film Homage to Edvard Munch and All My Dead

Children (1998) shows the artist on the pier near Munch’s house, naked and

prostrate in the foetal position, the dawn rising over the water as she lifts

her head and screams – a guttural response to great painter’s iconic image.

In 1998, Emin created My Bed, an uncensored presentation of her most

personal habitat. The double bed has become abstracted from function as it sits

on the gallery floor, in conversation with art history and a stage for life

events: birth, sleep, sex, depression, illness, death. The accumulation of real

objects (slippers, condoms, cigarettes, empty bottles, underwear) on and around

the unmade bed builds a portrait of the artist with bracing matter-of-factness,

defying convention to exhibit what most people would keep private. The work

gained international attention as part of the Turner Prize, entering Emin into

public consciousness. Another work that became a byword for her art of

disclosure was the sculpture Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963−1995 (1995,

destroyed 2004), where the names of all those she had ever shared a bed with –

friends, lovers and family – were sewn on the inside of a tent, a crawl-space

that invites the viewer to reflect on their own inventory.

Explicitly feminist, and acknowledging the influence of her friend and

collaborator Louise Bourgeois, Emin’s choice of medium is integral to the story

she tells. In hand-embroidered blankets and quilts, traditionally associated

with women’s work, she pierces the visual field with words, combining scraps of

different material with uneven stitching to spell out statements whose syntax

and spelling remain uncorrected. With titles such as Mad Tracey from

Margate. Everyone’s been there, (1997) or Hellter Fucking Skelter (2001),

they register the artist’s acute sensitivity to the views of those around her

and give a riposte, just as the medium is a riposte to the classification of

fine art, for centuries dominated by male artists. As she herself became

newsworthy, both nationally and internationally, Emin used the publicity to

prick other forms of decorum in the professional art world – such as never

over-explaining. In longer form, her memoir, Strangeland (2005)

offers an account of her journey to becoming ‘a fucked, crazy, anorexic-alcoholic-childless,

beautiful woman. I never dreamt it would be like this.’ The text is riddled

with spelling mistakes that challenge the form and carry through a sense of

unfiltered process, as was also the case with her long-running newspaper column

for The Independent (2005–09), in which she narrated her weekly

goings-on under the title ‘My Life in a Column’.

Emin’s ongoing series of neons features snatches of text in her recognisable

slanted handwriting, elevating fleeting thoughts and feelings as aphorisms: You

touch my Soul (2020), I Longed For you (2019) or I don’t

Believe in Love but I believe in you (2012). Her formulation of statements

in the second person has the effect of placing the viewer squarely in the

situation, and can encapsulate an entire romance in a pithy phrase, as

in I want my time with You (2018), a twenty-metre-wide neon that

greets passengers at London’s St Pancras Station. A critical part of her

practice since the 1990s, the neons evoke the seafront lights of Margate, latent

with the sense of dusk and faded glamour. Her birthplace is an abiding subject;

it resurfaces in large-scale sculptures, where reclaimed wood and found

materials are assembled in jagged structures that allude to the beach, pier,

huts and tide markers. Margate’s famous theme park ‘Dreamland’ is referred to

in several works, among them Self-Portrait (2001), which recreates the

pleasure ground’s helter-skelter, and It’s Not the Way I want to

Die (2005), which recalls the undulating roller-coaster in rickety, worn wood,

fragile to the point of collapse. Margate is ‘part of me’, Emin says, and while

looking back she is now looking to the future with the establishment of TKE

Studios, a new art school and artists’ studios.

Questions of mortality and the centrality of the female reproductive body

drive The Mother (2021), one of Emin’s most significant public sculptures.

Permanently sited next to the new Munch Museum, Oslo, it marks the death of her

own mother, and brings her lifelong admiration for Munch full circle. Fifteen

tonnes of bronze standing nine metres high, this woman with ‘her legs open to

the Fjord’ is visible from afar over land and water, a monument to the female

figure as protector without compromising on her vulnerability or eroticism. By

contrast, Baby Things, Emin’s accurate rendering of children’s tiny lost

shoes and clothes in bronze, was installed as if by chance outside the British

Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2007) and around Folkestone Triennial (2008),

intimate tokens that might inadvertently provoke a range of reactions, from

fear for those we love most, to the indifference with which we treat a

discarded object.

Most recently, Emin’s work has been charged by the seriousness of her medical

situation, since in 2020 she was diagnosed with bladder cancer. Self-portraits

taken on her camera phone in bed find the artist facing her ‘crippling’

insomnia in the small hours, and in recovery from extensive surgery. Her

paintings of the nude figure have a tempestuous energy. Emin’s graphic line, by

turn delicate or vigorous, imparts a sense of urgency; with each abandoned and

assertive gesture, she is flaying herself open. Drips and obliterations point

to the fluidity of the body, as it fluctuates between joy and suffering on its

journey between birth and death. Explosions of colour allude to a self that is

overcome by feeling and triumphing in sheer sensuality.

Tracey Emin was born in 1963 in London. She currently lives and works between

London, the South of France, and Margate, UK. Emin has exhibited extensively

including major exhibitions at Royal Academy of Arts, London (2020); Musée

d’Orsay, Paris (2019); Château La Coste, Aix-en-Provence, France (2017);

Leopold Museum, Vienna (2015); Museum of Contemporary Art, Miami (2013); Museo

de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (2012); Turner Contemporary, Margate,

UK (2012); Hayward Gallery, London (2011); Kunstmuseum Bern (2009); Scottish

National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (2008); Centro de Arte Contemporáneo,

Malaga, Spain (2008); Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (2003); and

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2002).

In 2007 Emin represented Great Britain at the 52nd Venice Biennale and her

installation My Bed has been included in ‘In Focus’ displays at Tate

Britain with Francis Bacon (2015), Tate Liverpool with William Blake and also

at Turner Contemporary, Margate alongside JMW Turner (2017). In 2011, Emin was

appointed Professor of Drawing at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, and in

2012 was made Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for

her contributions to the visual arts.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)