ADRIANO PEDROSA

CURATOR OF THE 60th INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION OF LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA

FOREIGNERS EVERYWHERE

The title of the

60th International Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia is drawn from a

series of works made by the Paris-born and Palermo-based collective Claire

Fontaine since 2004. The works consist of neon sculptures in different colors

that render in a growing number of languages the expression “Foreigners

Everywhere”. The expression was in turn appropriated from the name of a

collective from Turin that in the early 2000s fought racism and xenophobia in

Italy: Stranieri Ovunque. There are currently some 53 languages in Claire

Fontaine’s series of neon scultpures, both western and non-western, including

several indigenous languages, some that are in fact extinct—they will be

exhibited at the Biennale Arte this year in a new, large-scale installation in the

iconic Gaggiandre shipyards in the Arsenale.

The backdrop for the work

is a world rife with multifarious crises concerning the movement and existence

of people across countries, nations, territories and borders, which reflect the

perils and pitfalls of language, translation, nationality, expressing

differences and disparities conditioned by identity, nationality, race, gender,

sexuality, freedom, and wealth. In this panorama, the

expression Foreigners Everywhere has several meanings. First of all,

that wherever you go and wherever you are you will always encounter

foreigners—they/we are everywhere. Secondly, that no matter where you find

yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner. In addition,

the expression takes on a very particular, site-specific meaning in Venice: a

city whose original population consisted of refugees from Roman cities, a city

that was at one point the most important centre for international trade and

commerce in the Mediterranean, a city that was the capital of the Republic of

Venice, dominated by Napoleon Bonaparte, and taken over by Austria, and whose

population today consists of about 50,000 residents that may reach 165,000 in a

single day during peak seasons due to the enormous number of tourists and

travelers—foreigners of a privileged kind—visiting the city. In Venice,

foreigners are everywhere. Yet one may also think of the expression

as a motto, a slogan, a call to action, a cry— of excitement, joy or

fear: Foreigners Everywhere! More importantly, it assumes a critical

signification today in Europe, around the Mediterranean and in the world, when

the number of forcibly displaced people hit the highest in 2022, at 108.4

million according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and is

expected to have grown even more in 2023.

Artists have always

traveled and moved about, under various circumstances, through cities,

countries and continents, something that has only accelerated since the late

20th century—ironically a period marked by increasing restrictions

regarding the dislocation or displacement of people. The Biennale Arte 2024’s

primary focus is thus artists who are themselves foreigners, immigrants,

expatriates, diasporic, émigrés, exiled, or refugees—particularly those who

have moved between the Global South and the Global North. Migration and

decolonization are key themes here.

…………………………..

………………..

…………………..

A CELEBRATION OF THE

FOREIGN, THE DISTANT, THE OUTSIDER, THE QUEER, AS WELL AS THE INDIGENOUS

On a personal level, I

myself feel implicated in many of the Exhibition’s themes, concepts, and motifs

and in its framework. I have lived abroad and have been fortunate to travel

extensively during my lifetime. Yet, I have often experienced treatment typically

reserved for a Third World foreigner—although I’ve never been a refugee, and in

fact, I hold one of the highest-ranking passports from the Global South,

according to the Henley Passport Index. I also identify as Queer—the first

openly Queer curator in the history of the Biennale Arte. Moreover, I come from

a context in Brazil and in Latin America where the Indigenous artist and the

artista popular play important roles; although they have been marginalised in

art history, they have recently come to receive more recognition. Brazil is

also home to many diasporas; it is a land of foreigners as it were: besides the

Portuguese who invaded and colonised the country, it is home to the largest

African, Italian, Japanese, and Lebanese diasporas in the world.

Biennale Arte, an international event with so many official participating countries, has always been a platform for the exhibition of works by foreigners from all over the world. In this long and rich tradition, the 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, will be a celebration of the foreign, the distant, the outsider, the Queer, as well as the Indigenous.

In conclusion, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the board of La Biennale di Venezia and to former president Roberto Cicutto, who appointed me the Artistic Director of the Visual Arts Department in December 2022, in charge of curating Biennale Arte 2024. His only request was for me to construct an exhibition full of beauty. I gather we are delivering a foreign, strange, uncanny, and Queer sort of beauty.

LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 60th INTERNATIONAL

ART EXHIBITION

STATEMENT BY PIETRANGELO BUTTAFUOCO PRESIDENT OF LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA

This 60th edition of the International

Art Exhibition is all there in the title Foreigners Everywhere – Stranieri

Ovunque. Strong words, explosive when paired that evoke both current scenarios

and possible universes, on whose borderline the curator’s line of thought is

constructed, sharp in its longer focus and vibrant with complex contrasts

nearer to hand.

Adriano Pedrosa has

curated a Biennale Arte that reflects his personal approach to study and

research, which is free of any prejudice in favour of the already established –

where the vertigo of the unknown is an integral part of the process of

exploration and enjoyment, and disorientation becomes a potent instrument for

identifying new compass points.

And the compass is

important to understanding this paradigm shift. Pedrosa is the first South

American curator of the Biennale Arte and he is well aware that the compass

points themselves are anthropized symbolic forms, with the North at the head –

complete with a tall hat – and the South at the foot, a bare foot needless to

say.

A stranger among strangers is the (barefoot) wanderer making his way along the most daunting of goat tracks, the beggar under whose rags a God may be hiding, that deity unknown to himself from whom the renewal of dynasties springs. He is Aeneas quitting the flames of Troy to found – as a foreigner – a universalising civilization where no one is a barbarian and all are citizens. This is the principle guiding the selection of the artists, privileging those who have never previously participated in the Exhibition. Casting unaccustomed light on the paths of Modernism outside the Anglosphere. Foregrounding overlooked geographies on the margins of current dictates, albeit clear enough on the mappa mundi. Giving substance to voids that were never such – akin to what is going on in Rachel Whiteread’s sculptures – and coming back, finally, to auroral thinking, to that nostalgia for things that never had a beginning – as we see in language too, as the flatus vocis acquires meaning.

Pedrosa explains, with explicit reference to Oswald de Andrade’s Manifesto antropófago, how it was necessary for the ‘Modernisms’ of the global South to cannibalise hegemonic postcolonial cultures in order to establish themselves. A form of artistic resistance that in the case of Brazil recalls the pre-invasion cannibalistic rituals of the Tupinambá people. De Andrade was in fact inspired to write his Manifesto by a painting of Tarsila do Amaral entitled ‘Abaporu’, which in the Tupi language means “the man who eats people.” And it is eating, nourishing oneself, that constitutes for him a sacred root – and certainly not a mere anthropological phenomenon – as in the familiar Mediterranean example of those two provocateurs, Dionysus and, later, Jesus the Nazarene. Two versions of the resurrected ‘slain God’, two banquets attended by people eating other people: Dionysus – born from the thigh of his father Zeus, torn to shreds, chewed up and swallowed by the Maenads – and Jesus, son of Mary the Chosen One, become eucharistically the host in the liturgy, a presence in the rite and the embodiment of the Almighty’s promise, food for all.

This edition of the

Biennale Arte features both a contemporary and a historical nucleus, with a

large presence of Italian artists from the 20th-century diaspora, whose works

are displayed on the glass easels originally designed by architect Lina Bo

Bardi for the São Paulo Museum of Art. For the first time, an indigenous

Amazonian art collective – MAHKU (Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin) – also

takes centre stage, with a large-scale work on the facade of the Central

Pavilion. Seven hundred square metres of hallucinatory visions inspired by

sacred ayahuasca-based rituals, experiences mirrored by those – no less sacred

– that the Old Continent has experimented through, for example, Ernst Jünger’s

Annäherungen.

Two constant threads run

through the curator’s selection: an explicit desire to focus on works that

adopt the language of textiles; and the blood kinship that connects several of

the artists on show. A return, then, to the corporeal res extensa and to

visceral human relationships, understood as a repository of tradition and the

transmission of knowledge, in an age dominated by the immaterial and the

depersonalisation of form and content.

This Biennale Arte, then,

hosts samples of marginalised, excluded, oppressed beauty, erased by the

dominant matrices of geo-thinking. The interlacing themes of Pedrosa’s

Exhibition – the different, the foreigner, the journey, integration – will

reverberate nowhere better than in the calm and everrenewed waters of the lagoon

city. Once again Venice - over the centuries an open cradle of knowledge and

communication between peoples, ethnicities, religions - is the natural forum in

which to marshal new points of view and Fare Mondi (‘Making Worlds’) - to adopt

the local lexicon of an earlier Biennale Arte 2009.

The city that as many as

129 years ago had the idea of staging the first International Art Exhibition

thus renews its commitment to curiosity and the love of knowledge. That same

impulse that drove Marco Polo – the 700th anniversary of whose death will be

celebrated in this same 2024 – to meet and explore cultures seen as distant and

threatening: finding acceptance, as a foreigner in those lands, by virtue of a

sincere openness to human and equal exchange. Those were times when the Rialto

market teemed with languages, ethnicities, styles and vitality. And many

countries had Fondeghi – trade centres in modern terms – in Venice: Turks,

Syrians, Germans… showcasing their goods and expertise. Biennale Arte – with

its National Pavilions, artefacts, artists and visitors from all over the world

– was already there in embryo.

For Venice, in fact,

diversity has stood from the outset as a basic condition of normality. A

process of mirroring and confrontation with the Other, never perceived in terms

of denial or rejection. Pedrosa has been on an elevenmonth-long physical and

mental journey, taking in Chile, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, Puerto Rico,

Guatemala, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Angola, South Africa, Singapore, Indonesia, the

Middle East, before landing here in the lagoon to construct his own Fable of

Venice, his Sirat al Bunduqiyyah. Venice is the only European city to have had,

since 1000 AD, a name in Arabic. A constellation of meanings that functions as

a fine counterpoint to the 60th International Art Exhibition. Bunduqiyyah:

different, mestizo, mixture of peoples, foreigner.

THE TÜRKİYE PAVILION

PRESENTS HOLLOW AND BROKEN: A STATE OF THE WORLD

BY GÜLSÜN KARAMUSTAFA AT THE 60TH INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION OF LA BIENNALE

DI VENEZIA

Arsenale, Sestiere

Castello Campo della Tana 2169/F Venice 30122

April 20, 2024 – November 24, 2024

The Türkiye Pavilion

presents Hollow and Broken: A State of the World, a site-specific

installation by Gülsün Karamustafa, one of Türkiye’s most influential and

outspoken artists, at the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di

Venezia.Situated in the Arsenale’s historic Sale d’Armi, the exhibition runs

from 20 April to 24 November, with its pre-opening on 17, 18 and 19

April.Karamustafa’s installation invites viewers to consider the tragic and

tumultuous realities of a world impacted by wars, earthquakes, migration and

nuclear peril. Comprising an interconnection of sculptural works that champion

her use of disparate materials, the premiere of a new film, and a sound

installation, these works reflect her perception of the world as broken and

empty.

Space plays a central

role in the exhibition, with Karamustafa drawing inspiration from the

rectangular shape of the Sale d’Armi, reminiscent of the dimensions of the

historical Hippodrome of Constantinople in Istanbul, and the building’s former

history, reinforcing her connection with the surroundings. Upon entering the

Pavilion, visitors encounter three striking chandeliers suspended from above,

crafted from discarded Venetian glass, each representing a monotheistic faith:

Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. These luminous symbolic objects are shrouded

in a web of barbed wire – conveying the historic tensions and quarrels between

each religion and serving as a lens through which she explores the state of our

world today.

This concept echoes

Karamustafa’s 1998 artwork, Trellis of My Mind, a 20-metre frieze composed

of 300 colourful religious illustrations from Islamic, Christian, and Jewish

manuscripts. The artwork portrays the intersection and coexistence of these

religions, drawn from her experiences living in Istanbul. Despite their shared

narratives, Karamustafa acknowledges these religions have endured perpetual

conflict throughout history and continue to be shaped by her personal memories

of past wars.

Hollow, plastic moulds

that resemble concrete columns are scattered throughout the space, the choice

of materials starkly contrasting the traditional associations to glory,

artillery and power. The column moulds, supported only by propping devices,

embody the artist’s feelings of emptiness and brokenness in the current world –

their vacant nature is accentuated by lighting, contrasting the ‘force’ of

columns inherent in architecture – stability, prowess, durability, and victory.

Shattered Venetian glass

emerges as a recurring motif within the installation as a material that

resonates deeply with Karamustafa’s feelings. Situated within the Pavilion are

four dismantled wheeled carts – with their ends cut off on either side – loaded

with discarded remnants of Murano glass shards, evoking the transportation of

heavy cargo. Propped up solely by rails, the carts give the impression that

they’re floating, albeit constrained by their restricted movement. These works

establish a direct link to the historical significance of the Sale d'Armi, once

Venice’s largest production centre during the pre-industrial era and a potent

symbol of military power.

Premiering for the first

time is a new film by the artist, comprising black and white images from found

propaganda footage depicting migration, war, and demonstrations from around the

globe. Originally screened in cinemas, these images have been reimagined by

Karamustafa, devoid of the cameraman’s original viewpoint, to spotlight the

human condition. By reframing this material, the film delves deeper, shedding

light on the suffering of the individuals captured in the footage. The film

interweaves all elements of the artist’s installation into an impactful

statement. An accompanying sound composition both envelopes and shadows the

movement of visitors, where a deep, resonant tone fills the air, fluctuating in

intensity as it traverses the exhibition space.

“What I am dealing with” Karamustafa

says of this work, “is the state of a world hollowed out to the core by

wars, earthquakes, migration and nuclear peril unleashed at every turn,

threatening humankind while nature is ceaselessly scathed and the environment

made sick. I attempt to physically and emotionally summon into existence this

phenomenon: the emptiness, the hollowness, the brokenness produced by the

devastation that has become commonplace, whose pace becomes ever more

impossible to keep up with, by the unimaginable grief that keeps on striking

again and again at relentless intervals, by empty values, identity struggles

and brittle human relationships.”

ABOUT GÜLSÜN KARAMUSTAFA

Gülsün Karamustafa

(b.1946) is one of the most influential artists for younger generations.

Through her art practice, spanning the course of over fifty years, she focuses

on such topics as the modernisation of Türkiye, uprooting and memory,

migration, locality, identity, cultural difference and gender from an array of

perspectives. Within her works, which stem from both personal and historic

narratives, she champions the use of disparate materials and methods. Through

media as diverse as painting, installation, photography, video and performance,

she calls into question historical injustices in the social and political

fields.

Karamustafa has

participated in numerous international biennials, including Istanbul, TR; São

Paulo, BR; Gwangju, KR; Kyiv, UA; Singapore, SG; Havana, CU; Thessaloniki, GR;

Sevilla, ES. She has presented solo exhibitions at major institutions and

galleries worldwide, including Salt Beyoğlu and Salt Galata, Istanbul, TR;

Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum fürGegenwart, Berlin, DE; Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven,

NL; IVAM InstitutValenciàd’Art Modern, Valencia, ES; EMST National Museum of

Contemporary Art Athens, GR; Kunstmuseum Bonn, Bonn, DE; LundsKonsthall, Lunds,

SE; SalzburgerKunstverein, Salzburg, AT; KunsthalleFridericianum, Kassel, DE;

Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, DE, among others.

Her works have been

included in the permanent collections of Centre Pompidou, Paris, FR; Tate

Modern, London, GB; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, US; Museum of

Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago, US; Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris, FR; Van

Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, NL; Ludwig Museum, Cologne, DE; MUMOK, Vienna, AT; Wien

Museum, Vienna, AT; Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, PL; Neues Museum

Nürnberg, Nuremberg, DE; EMST National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens,

Athens, GR; Istanbul Modern Art Museum and Arter, Istanbul, TR.

She received the

RoswithaHaftmann Prize in 2021 and Prince Claus Award in 2014.

The artist lives and

works in Istanbul and Berlin.

EDITH KARLSON: HORA LUPI, ESTONIAN PAVILION AT

THE 60th INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION – LA BIENNALE

DI VENEZIA

Church of Chiesa di Santa

Maria delle Penitenti, Cannaregio, 893–894

April 20, 2024 – November

24, 2024

Edith Karlson will present Hora lupi for the Estonian Pavilion at the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia from 20 April 2024 until 24 November 2024. Presented at the church of Chiesa di Santa Maria delle Penitenti, the exhibition explores primitive human urges in their banality and solemnity and questions the possibility of redemption in a world that is never worthy of it. Located in Cannaregio overlooking the district’s canal, the arresting interior of the church, which dates back to the 18th century, helps to build the emotional atmosphere of the exhibition. Here, everything is left unchanged, even the dust of the centuries past remains. Lying in abandonment, Karlson uses the space as a metaphor for being human, equally sad, and incomplete. Full of cracks and fissures, through which eventually, perhaps, a redeeming light will shine. The exhibition spaces are filled with clay and concrete sculptures that evoke the inevitable misfortune of being born, and the always-endeavouring nature of being human. The title of the exhibition Hora lupi (hour of the wolf) refers to a mythical time before dawn, when things arise and disappear – an hour of deep darkness but also of transformation. It is believed to be the time of night, when the most people are born and die. The exhibition centres around a vast series of handcrafted clay self-portraits created by people who surround the artist: children and elderly people, state officials and common workers – a gallery of contemporary faces that will someday become their memorial. The sculptures are inspired by the 14th century terracotta sculptures in St. John’s Church in Tartu, Estonia, most likely depicting townspeople of the time. It has been suggested that the sculptures are a memorial ensemble commemorating the victims of the plague. Sculptures by Karlson reside in the remaining rooms of the church, including the artist’s recognisable anthropomorphic figures inspired by folklore and mythology: as waves from passing vaporetti gently crash through a gaping hole in the collapsed floor, we see weremermaids perched on the verge of its opening. For Hora lupi, Karlson presents an existential narrative of the animalistic nature of humans. Depicting that the sincerity and bluntness of instinct can sometimes take a brutal and violent form, but also poetic and at times a little absurd, gentle, and melancholy. So, by and large, the theme of the exhibition for the Estonian Pavilion at La Biennale Arte 2024 could be concluded as “our world today”.

ABOUT EERO EPNER

Eero Epner is an art historian, dramaturge and writer who has worked for the avant-garde theatre NO99 as well as with many Estonian artists. He worked with Edith Karlson for her last large-scale show Return to Innocence (Estonian Contemporary Art Museum, 2021). He was granted the Estonian Cultural Endowment’s award for researching and introducing the works of Konrad Mägi, an Estonian artist from early 20th century in 2017. Participating since 1997, this is the 14th time Estonia is exhibiting at the Venice Biennale. The Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art is the official representative of the Estonian exposition, and it is financed by Estonian Ministry of Culture.

ABOUT EDITH CARLSON

Edith Karlson is a sculptor who often presents her work as installation, using an entire exhibition space. Her works tackle the most inexplicable feelings and sensations in the current world: fear, melancholy, brutality and joy, which she transforms into material form, often in clay, concrete or found materials. Frequently working with animal forms and anthropomorphic figures, she approaches humans as animalistic beings whose impulses, wants, and desires are hidden just under the surface of their wellpressed suits. Karlson studied installation and sculpture at the Estonian Academy of Arts (BA, 2006; MA, 2008). She was awarded the EAA Young Artist’s Prize (2006) and Köler Prize People’s Choice Award (2015). Karlson is among the recipients of the national artists’ salary between 2018-2020 and 2022-2024 and was granted the Estonian Cultural Endowment’s main award (2020).

PAVILION OF THE UNITED STATES 60TH INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION –

LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA - THE SPACE IN WHICH TO PLACE ME BY JEFFREY GIBSON

April 20, 2024 – November

24, 2024

Presented by Portland Art

Museum, Oregon, and SITE Santa Fe, New Mexico Commissioners: Louis Grachos,

Executive Director, SITE Santa Fe; Kathleen Ash-Milby, Curator of Native

American Art, Portland Art Museum; Abigail Winograd, Independent Curator

Curators: Kathleen

Ash-Milby, Abigail Winograd

Portland, OR and Santa

Fe, NM – April 17, 2024 – The United States Pavilion at the 60th International

Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia presents a multidisciplinary

exhibition by Jeffrey Gibson, an artist recognized for a hybrid visual language

that employs abundant color, complex pattern, and text to articulate the

confluence of American, Indigenous, and Queer histories and imagine new

futures. Gibson’s exhibition for the U.S. Pavilion, the space in which to place

me, engages concepts that have shaped the artist’s practice over his 20-year

career. Bringing together sculpture, multimedia paintings, paintings on paper,

and video, the exhibition explores the dimensions of collective and individual

identity and the forces that shape its perception across time.

The 2024 U.S. Pavilion is

presented by Portland Art Museum in Oregon and SITE Santa Fe in New Mexico, in

cooperation with the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and

Cultural Affairs. The Pavilion is commissioned by Kathleen Ash-Milby, Curator

of Native American Art at the Portland Art Museum and a member of the Navajo

Nation; Louis Grachos, Phillips Executive Director of SITE Santa Fe; and

Abigail Winograd, independent curator. The exhibition is curated by Winograd

and Ash-Milby, who is the first Native curator to organize a U.S. Pavilion.

Gibson joins an esteemed group of contemporary artists who have represented the

United States on the Biennale Arte’s global stage and, as a member of the

Mississippi band of Choctaw Indians and of Cherokee descent, he is the first

Indigenous artist to represent the country with a solo exhibition.

the space in which to

place me considers Indigenous histories within an American and international

context, expanding upon the varied materials and forms that Gibson has employed

over the past two decades. The title references Oglala Lakota poet Layli Long

Soldier’s Ȟe Sápa, a poem whose geometric shape parallels Gibson’s meditation

on the physicality of belonging. Gibson often draws influence from poetry and

literature, as well as music, fashion, and theory, which materialize in his

intuitive use of text. This long-held engagement continues throughout the space

in which to place me. Gibson incorporates language from foundational American

documents from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including constitutional

amendments, legislation, speeches, and official correspondence, as well as song

lyrics and musical references. Often pointing toward moments in history that

were meant to spark change, Gibson’s use of text encourages viewers to examine

our past when considering the present.

“This exhibition extends

the timeline of Indigenous histories,” said Ash-Milby. “Jeffrey combines

ancient aesthetic and material modalities with early 19th and 20th century

Native practices to propose an Indigenous future of our own determination. I’m

honored to be a part of this historic project, and I especially look forward to

seeing how Native communities and students engage with the work as a tool for

innovation and healing.”

“Few artists working

today are so expert in engaging our hearts and our collective conscience.

Operating within and beyond the constructs of the contemporary canon, Jeffrey

proposes alternate worlds that embrace our shared humanity and create space for

joy while acknowledging hardship,” said Winograd. “I’m so proud to bring

Jeffrey’s worldview to the Venice Biennale, where he activates the U.S.

Pavilion in a manner truly unlike anything that’s come before it.”

“It’s been a privilege to

witness how this exhibition has come together over many months and across

multiple states. Seeing the murals, which were created in Santa Fe, installed

in Venice is a particularly resonant moment that encapsulates, for me, the

collaborative experience of this project,” said Grachos. “Helping to realize

Jeffrey’s vision for this monumental exhibition has been a great joy, and it’s

the kind of work that is core to SITE Santa Fe’s mission of supporting artistic

innovation.”

“This exhibition will

introduce an international audience to Jeffrey’s powerful work for the first

time, and, in turn, to the complex histories of our country and of Native

people,” said Brian Ferriso, Director of the Portland Art Museum. “We are

grateful to be a part of such a significant global moment, and to help provide

opportunities for access and education that are so essential to Jeffrey’s work

and the values of the Portland Art Museum.”

In conjunction with the

presentation at the U.S. Pavilion, Gibson and the commissioning institutions

are collaborating with two educational partners, the Institute of American

Indian Arts (Santa Fe, NM) and Bard College (Annandale-on-Hudson, NY) to realize

programming that connects Indigenous, Native American, and international

undergraduate humanities students, graduate art students, and the public.

ABOUT THE SPACE IN WHICH

TO PLACE ME

For the U.S. Pavilion,

Gibson has created an exhibition of new and recent work that invites viewers to

examine collective history and its capacity to prescribe a societal center and

periphery. With the space in which to place me, Gibson reorients this

established framework and creates a new nexus that makes room for generations

of marginalized voices.

The exhibition begins in

the pavilion’s forecourt with the titular work: a large-scale, site-specific

sculpture that combines a series of classical bases in a multi-level platform

painted in a singular, vibrant red. Encouraging public interaction, the

installation offers a site for celebration, respite, and gathering. On opening

day, a dance program featuring members of the Colorado Inter-Tribal Dancers and

Oklahoma Fancy Dancers will inaugurate the space.

Beyond the forecourt, Gibson

wraps the neoclassical building in hand-painted murals that explode with his

signature expression of color, pattern, and text. Extending across the eastern

and western facades of the building are two introductory phrases: the title of

the exhibition on the left is joined on the right by “We hold these truths to

be self-evident,” an opening line from the United States’ Declaration of

Independence, which preludes Gibson’s integration of foundational American

documents throughout the exhibition.

Surrounding the exterior

facade is a series of eight flags, each mounted on twenty-foot-tall teepee

poles and patterned in their own unique design. Flags have been a part of

Gibson’s practice since 2012 when he first constructed them from recycled army

blankets and painted directly on the wool. Often a marker of territory or a

signal of affiliation, here Gibson’s vibrant, geometric flags represent

inclusivity, welcoming visitors to a space that acknowledges collective memory

alongside individual experience.

Entering the pavilion’s

first gallery, visitors encounter two towering figures, The Enforcer (2024) and

WE WANT TO BE FREE (2024). Standing approximately 10 feet high, the figures

take their shape from beads, ribbon, fringe, and tin jingles—elements inspired

by traditional Native regalia. Their heads, rendered imperfect and asymmetrical

in glazed ceramic, reference Mississippian effigy pots, an ancient tradition

from the American Southeast. Their bodies bear beaded text on each side: The

Enforcer’s chest refers to the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the U.S.

Constitution, known as the “Reconstruction Amendments,” which abolished slavery

and intended to protect the civil rights of Black American citizens. Also

referenced is the Enforcement Act of 1870, which established penalties for

interfering with a person’s right to vote. WE WANT TO BE FREE is emblazoned on

the front of the adjoining figure, whose additional text refers to the Indian

Citizenship Act of 1924, a law granting basic rights to Indigenous people within

U.S. boundaries, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the first federal law to

define citizenship and claim all citizens equal under the law. On a mural

behind the figures are the words of Martin Luther King Jr.: “We are made by

history,” a phrase employed by King in 1954 to urge his congregation to take an

active role in their futures, and one that Gibson borrows here to emphasize how

our reality is shaped by our past.

Gibson continues to

approach these ideas in the next gallery, where two beaded bird sculptures, we

are the witnesses (2024) and If there is no struggle there is no progress

(2024), perch atop stone pedestals. A consistent motif in Gibson’s practice,

the birds are inspired in part by “whimsies,” Victorian era Nativemade objects,

which were originally created to appeal to the taste and aesthetics of the

period. Once viewed as kitsch, the objects fell outside of culturally specific

definitions, which is what drew Gibson to them initially. More than just a

source of inspiration, Native-made objects are integrated in the paintings on

paper on view in the second and fourth galleries. Gibson sourced examples of

traditional Native beadwork, which includes bags, belts, and medallions from

websites and estate and garage sales. Applying them first to a felt base and

then to painted cotton rag paper, the objects are attached to the surface of

the paintings with care and kept intact in their original form. This method of

construction allows the objects, whose makers are unknown, to be easily removed

if a viewer is able to identify the object and maker. In the event that an

object is claimed, Gibson has committed to returning the work and commissioning

an Indigenous artist to create a replacement or to make one in his studio. The

objects introduce a physical dimension to the kaleidoscopic works on paper, as

seen in ACTION NOW ACTION IS ELOQUENCE (2024), which incorporates a vintage

beaded belt that still holds the curved shape of its original wearer.

Gibson has swathed the

walls of the rotunda in a deep red, reimagining the space as the beating heart

of the exhibition. At the center hangs one of the artist’s iconic punching

bags, created specifically for the U.S. Pavilion. Titled WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS

TO BE SELF-EVIDENT (2024), the bag’s multi-colored fringe cascades in diagonal

layers to the floor below. The beaded bag is precisely lit, while the rest of

the room remains dim, creating a space for respite and reflection at the

midpoint of the exhibition.

In the next gallery,

Gibson’s enduring exploration of hybridity takes a new form with I’M A NATURAL

MAN (2024), Be Some Body (2024), and Treat Me Right (2024) three busts elevated

to eye level on marble bases. Like many of Gibson’s figures, they are

intentionally indeterminate; their beaded skin and intricate hair cannot be

ascribed to any one specific culture or aesthetic. The busts also blur the

boundaries between historical eras—integrated among the swirling beads are

vintage pinback buttons with the language of advocacy groups and organizers,

such as the slogan “If we settle for what they’re giving us, we deserve what we

get!”. Surrounding the busts are related works on paper and large-scale

paintings, including THE RETURNED MALE STUDENT FAR TOO FREQUENTLY GOES BACK TO

THE RESERVATION AND FALLS INTO THE OLD CUSTOM OF LETTING HIS HAIR GROW LONG

(2024). The work’s title and its matching text draw from a 1902 letter from the

Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Superintendent of the school district of

Round Valley, California, in which a directive is given for male Indians to cut

their hair to “hasten their progress towards civilization.” Positioned in front

of these words are the three busts whose ribbon and beaded hair falls long past

their faces, a refusal rendered in defiant, electric color.

In the final gallery of

the exhibition, Gibson immerses viewers in a multi-channel video installation,

She Never Dances Alone (2020), a work originally shown in New York’s Times

Square. In the U.S. Pavilion, the video is projected simultaneously across nine

screens and features artist and dancer Sarah Ortegon HighWalking (enrolled

Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho) performing the Jingle Dress Dance, a

powwow dance that originated with the Ojibwe tribe. The centuries-old dance is

traditionally performed by women to call upon ancestors for strength,

protection, and healing. Dancing to the beats of First Nations electronic group

The Halluci Nation, Ortegon HighWalking performs in a series of her own dresses

adorned with jingles or rows of ziibaaska’iganan (metal cones). As the dance

progresses, her image multiplies within each screen and across the gallery,

representing generations of Indigenous women and acknowledging their

persistence for years to come. Inviting viewers to imagine a response to the

dance’s ancestral call, Gibson gestures toward a future that can be shaped by

acceptance and healing.

ABOUT JEFFREY GIBSON

Jeffrey Gibson (American,

born 1972) is the United States Representative to the 60th International Art

Exhibition in Venice. A member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and

of Cherokee descent, Gibson’s artistic practice combines Native art traditions

with the visual languages of modernism to explore the confluence of personal

identity, popular culture, queer theory, and international social narratives.

Across sculpture, painting, and collage, Gibson’s multi-disciplinary work

embraces ideas of hybridity and reveals intersections between contemporary

issues and past histories.

Gibson recently

collaborated with both commissioning institutions on presentations of his work.

Portland Art Museum commissioned Gibson’s site-responsive installation They

Come From Fire, which transformed the exterior windows of the façade as well as

its two-story interior Schnitzer Sculpture Court from October 2022 to April

2023. Gibson’s 2022 solo exhibition The Body Electric was organized by SITE

Santa Fe and debuted in Santa Fe before traveling to the Frist Art Museum in

2023.

Concurrent with the

opening of the Biennale Arte, Gibson’s work is on view in Jeffrey Gibson: no

simple word for time (Sainsbury Centre, Norwich) and Unravel: The Power and

Politics of Textiles in Art (Barbican Centre, London). A forthcoming solo

exhibition of the artist’s work will debut at The Massachusetts Museum of

Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) on October 13, 2024. A new mural by the artist,

created with MASS MoCA, will be on view in Boston's Dewey Square beginning June

1, 2024. Gibson has also been commissioned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in

New York to create new works for the Museum’s Fifth Avenue facade, which will

be unveiled in September 2025.

Recent solo exhibitions

and projects include Jeffrey Gibson: DREAMING OF HOW IT’S MEANT TO BE (Stephen

Friedman Gallery, London, 2024), Jeffrey Gibson: ANCESTRAL SUPERBLOOM (Sikkema

Jenkins & Co., New York, 2023), This Burning World: Jeffrey Gibson (ICA San

Francisco, 2022), Jeffrey Gibson: The Body Electric (SITE Santa Fe, 2022),

Jeffrey Gibson: They Come From Fire (Portland Art Museum, 2022), Jeffrey

Gibson: INFINITE INDIGENOUS QUEER LOVE (deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum,

2022), and Jeffrey Gibson: Like A Hammer (Denver Art Museum, 2018). In addition,

the artist was commissioned to create sets for the New York City Ballet’s

Copland Dance Episodes, which premiered in the fall 2023 season. Gibson’s work

was also exhibited in the 2019 Whitney Biennial.

Gibson has received many

distinguished awards, including a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

Fellowship Award (2019) and a Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors

Grant (2012). Gibson also conceived the landmark volume, An Indigenous Present

(2023), which showcases diverse approaches to Indigenous concepts, forms, and

mediums. He collaborated with Pavilion cocurator Abigail Winograd on their

co-edited monograph, Jeffrey Gibson: Beyond the Horizon (2022) which

accompanied the exhibition, Beyond the Horizon (2021-2022).

The artist’s work is

included in many permanent collections, including the Museum of Modern Art,

Whitney Museum of American Art, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Smithsonian

National Museum of the American Indian, National Gallery of Canada, Denver Art

Museum, and Portland Art Museum.

Gibson lives and works

near the Hudson Valley region of New York State. The artist holds a MFA from

the Royal College of Art, London (1998), a BFA from the School of the Art

Institute of Chicago (1995) and was awarded honorary Doctorates from the Institute

of American Indian Arts (2023) and Claremont Graduate University (2016). Gibson

is currently an artist-in-residence at Bard College.

ARCHIE MOORE: KITH AND KIN, AUSTRALIA PAVILION AT THE 60th INTERNATIONAL

ART EXHIBITION – LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA, CURATED BY ELLIE BUTTROSE

ARCHIE MOORE: KITH AND KIN, AUSTRALIA PAVILION AT THE 60th INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION – LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA, CURATED BY ELLIE BUTTROSE

April 20, 2024 – November

24, 2024

the phrase ‘kith and kin’

now simply means ‘friends and family’. however, an earlier old english

definition that dates from the 1300s shows kith originally had the added

meanings of ‘countrymen’ and also ‘one’s native land’, with kin meaning ‘family

members’. many indigenous australians, especially those who grew up on country,

know the land and other living things as part of their kinship systems — the

land itself can be a mentor, teacher, parent to a child. this sense of

belonging involves everyone and everything, and for first nations peoples of

australia, like most indigenous cultures, is deeply rooted in our sacred

landscapes from birth until death. i was interested in the phrase as it aptly

describes the artwork in the pavilion, but i was also interested in the old

english meaning of the words, as it feels more like a first nations

understanding of attachment to place, people and time.

when i was younger, i had

little interest in discovering my first nations roots and history — there was a

shame and embarrassment in being known as aboriginal. i once had to attain a

certificate of aboriginality for approval of a loan from a first nations

organisation — they asked for the surnames of my family and where they were

from, and that’s all they needed to confirm my status. this proof may be

required for employment in indigenous-identified positions, enrolling in

schools, for government loans and assistance, and for land rights claims, where

a continuous and unbroken connection to country since colonisation needs to be

proven. now, it is with pride i identify as aboriginal, and i see those

feelings of shame and embarrassment as a product of racism and the colonialist

project.

i became interested in

genealogy six years ago and started looking in the archives for information on

my mother’s kamilaroi and bigambul side, and my father’s british and scottish

side. when my mother had a stroke in 2016, i started to realise how much

information would be lost if she died. she also became more open about discussing

family history, and more lucid too. i have come across material in archives and

museums, on the national library of australia’s search engine trove, and i have

3484 people in the family tree on the genealogical website ancestry.

the family tree in kith

and kin is limited by recorded information — how far back written records go,

which is much sooner on my aboriginal side than my european side. i referenced

the genealogical chart from anthropologist norman tindale’s visit to

boggabilla, when he interviewed my maternal great-grandmother, jane clevin, in

1938. what tindale recorded from my great grandmother seems accurate and

correlates with what my mother has said, but it reflects a western idea of how

people are interconnected as a family. in indigenous kinship, there are several

people that you call ‘mother’ or ‘father’, and cousins are called ‘brothers’.

many researchers have traced descent as a way to categorise and document

aboriginal people, without necessarily understanding indigenous family

structures.

my artwork also

historicises terms now considered highly derogatory to mark a time in australia

when these terms were more commonly used in the language of cultural conflict.

the words ‘black’, ‘full blood’, ‘halfcaste’, and ‘quadroon’ were common descriptions

on government records, which seems to reaffirm the racist myth of a ‘dying

race’, as if first nations peoples could be bred out. ‘gin’ and ‘lubra’ are

indigenous words for woman/wife but have come to be used as pejorative terms,

often in connection with the sexual exploitation of aboriginal women by

colonisers. this shows how language can become weaponised, and also the

european settlers’ need for classification. i found these racist words in

archival documents about my family — often about members, like my grandparents,

who couldn’t read or write. i don’t believe the inclusion of the words in kith

and kin reinstates their usage, as indigenous peoples refuse to occupy and

entertain the terms’ denigrated meanings

some of the names i’ve

used in the family tree have anglo first and surnames. there are also joke

nicknames from the 19th century, like ‘one eyed jack’ and just a singular first

name that is a shortened version of the proper name, like ‘bobby’ instead of ‘robert’.

if a surname exists, sometimes it was assigned by the pastoralists who were

putting their surname or the property’s name on indigenous people. higher up on

the family tree, i use singular traditional aboriginal names. i’ve tried to

write as many kamilaroi names as i can.

over 550 first nations

people have died in the state’s care in the years since the royal commission

into aboriginal deaths in custody 1987-1991. the redacted coroners’ reports and

archival material of my family members hover above a pool of water, facing

their ancestors at the furthest reaches of the family tree — in and between the

stars. with no one held accountable for any death in custody, and many of the

339 recommendations of the commission yet to be acted upon, the volume of cold

administrative documents visualises the scale of inaction. the stillness and

quiet of the space serve as a memorial or shrine — a place for reflection and

remembrance of all of those who have come before us.

the family tree shows a

65,000+ year scope of time. i wanted to show how long aboriginal cultures have

existed and — in spite of invasion, massacres, and systemic over-incarceration

— continue to exist into the now. the drawing begins as a representation of

genealogical descendancy and time in a western linear sense, but as we go back

a few hundred years it resembles more of a first nations notion of kinship and

time, where the present, past and future share the same space in the here and

now. the australian anthropologist william edward stanner conveyed the idea in

his germinal 1956 essay the dreaming, in which he coined the term ‘everywhen’:

‘one cannot “fix” the dreaming in time: it was, and is, everywhen’.

ELLIE BUTTROSE ON KITH

AND KIN

I. historiography

first nations peoples of

australia are among the oldest continuous living cultures on earth. archie

moore’s kith and kin is both evidence and reminder of this fact, tracing the

artist’s aboriginal relations from the kamilaroi and bigambul nations over

65,000+ years up the walls and across the ceiling of the australia pavilion. it

is a continuation of archie’s ongoing assertion of the sovereignty (and

reflections on the subjectivity) of indigenous australians in his artistic

practice. in school, archie was taught that australia’s history started with

british colonisation in 1770, founded on the principle of terra nullius (land

belonging to no one), without reference to indigenous peoples who cared for the

continent for millennia. the artist’s choice of materials for this celestial

map of names — fragile chalk on blackboard — invokes the transmission of

knowledge and how what is taught within, and what is left out of, the

prevailing education system reverberates into the future with consequence.

II. kinship

the vast drawing traces

the artist’s personal history from himself, close kin, distant relatives,

segueing through racist slurs, and extending to countless generations of

ancestors. anthropologist norman tindale’s linear genealogical diagram that

professed to document archie’s aboriginal relations is exceeded by the greater

complexity of first nations kinship systems. kinship is the organising

principle for indigenous social relations and responsibilities, and

incorporates all living things including plants, animals, land and waterways.

archie’s drawing reaches so far into time that it captures the common ancestors

of all humans, a timely reminder that every person on the planet has kinship

duties to one another.

III. archives

the words that appear in

this linguistic taxonomy are taken from archives, newspapers and government

documents, and include names, racist slurs, and gamilaraay (the kamilaroi

nation’s language) and bigambul kinship terms. the inclusion of archie’s

ancestors’ languages enacts indigenous language maintenance. derogatory terms

and diminutive names attest to how language has been used to classify and

disempower first nations peoples. speculative names appear amongst the

ancestors to redress omissions in the written records on oral indigenous

cultures. holes occur throughout the family tree, these absences signal the

severing of familial ties through colonial invasion, massacres, diseases,

displacement and the deliberate destruction and suppression of archival

records. while archie represents his lived experience and his family’s history,

these chronicles resonate worldwide.

IV. memorialisation

another black void

occupies the centre of the pavilion. this reflective pool is a memorial for the

first nations individuals who have died in police custody since 1991.

indigenous australians are one of the most incarcerated people globally; they

comprise 3.8% of the australian population yet are 33% of prison inmates.1

above the water hover stacks of coronial inquests that date back to the royal

commission into aboriginal deaths in custody 1987–1991. appointed by the

australian government, it found that self-determination and addressing health,

schooling, employment, and housing inequality would contribute to a lower

incarceration rate.2 more than 30 years later, many of its recommendations have

yet to be implemented, and deaths continue unabated. the volume of coronial

inquests makes visible the vast scale of this preventable horror. by placing

this publicly available information at arm’s length archie articulates the gap

between knowledge and action. names have been redacted out of respect for the

deceased. reports that are not publicly accessible are represented with a blank

ream of paper, with these white voids expressing breaches in the record. the

administrative reports are cradled by the reflection of the family tree in the

water below, commemorating that each of the deceased belongs to this expansive

web of relations.

V. carceral

legacies australia’s

history is inextricably linked with the carceral system. british colonisation

was established with penal colonies from 1788. archie’s genealogy is

illustrative of this, with his british and scottish great-greatgrandfather

arriving as a convict in 1820; while his kamilaroi and bigambul great uncle was

imprisoned in the notorious boggo road gaol after accidentally killing his

father during a fight over their paltry wages. within the sea of coronial

inquests, archie incorporates archival records referencing his kin that

evidence how punitive laws and government policies have long been imposed upon

first nations peoples. these include reports by the protector of aboriginals

denying his grandparents exemption from the queensland government’s aboriginal

protection and restriction of the sale of opium act 1897, and subsequent

amendments that would have enabled them to access rights that non-indigenous

citizens enjoyed — such as freedom of movement, the ability to control their

money and the right to marry without approval. archie uses his family history

to make the systemic issues imposed upon first nations peoples uncomfortably

tangible

VI. time

kith and kin is an

extensive account of history — a vast abyss of time — yet it is a statement

told from one point of view. the fragility of archie’s perspective is reflected

in the impermanence of chalk that could seemingly be wiped away without a

trace. while his voice is singular, the vertiginous volume of names is

confirmation that archie’s position draws upon the knowledge of hundreds of

thousands of his forebears. in kamilaroi astronomy the ancestors reside in the

sky, including the dark patches between stars, and archie’s white drawing on a

black background resembles an astronomical chart. the artwork reaches into the

deep time of space and simultaneously into the future through the suggestion of

endlessly reproduced kinship connections. in the kamilaroi understanding of

time, the past, present and future co-present (a view shared by other first

nations in australia). by placing 65,000+ years of family on a single

continuum, kith and kin immerses audiences in the co-presence of ancestors and

the co-existence of time, and by doing so archie enfolds each of us into the

everywhen.

1. thalia anthony,

‘factcheck: are first australians the most imprisoned people on earth?’, the

conversation, 6 june 2017, , viewed 1 february 2024. australian bureau of

statistics. ‘estimates of aboriginal and torres strait islander australians.’

abs, 30 june 2021, , viewed 1 february 2024. australian bureau of statistics.

‘prisoners in australia’, abs, 2023, , viewed 1 february 2024.

2. ‘recommendations’,

national report volume 5, royal commission into aboriginal deaths in custody,

australasian legal information institute: indigenous law resources, , viewed 1

february 2024.

NUCLEO CONTEMPORANEO BY

ADRIANO PEDROSA

The Italian stranieri, the Portuguese estrangeiro,

the French étranger, and the Spanish extranjero, are all etymologically connected to the strano, the estranho, the étrange, the extraño, respectively, which is

precisely the stranger. Sigmund Freud’s Das Unheimliche comes

to mind—the uncanny in English, which in

Portuguese has indeed been translated as “o estranho”–the

strange that is also familiar, within, deep down side. According to the

American Heritage and the Oxford Dictionaries, the first meaning of the word

queer is strange, and thus the Exhibition unfolds and

focuses on the production of other related subjects: the queer artist, who has moved within different

sexualities and genders, often being persecuted or outlawed; the outsider artist, who is located at the margins of

the art world, much like the self-taught artist, the folk artist and the artista popular; as well as the indigenous artist, frequently treated as a

foreigner in his or her own land. The productions of these four subjects are

the interest of this Biennale Arte, constituting the International

Exhibition’s Nucleo Contemporaneo, and although

their work is often informed by their own lives, experiences, reflections,

narratives and histories, there are also those who delve into more formal

issues with their own strange, foreign or indigenous accent.

Indigenous artists have

an emblematic presence in the International Exhibition, and their work greets

the public in the Central Pavilion, where the Makhu collective from Brazil will

paint a monumental mural on the building’s façade, and in the Corderie in the

Arsenale, where the Maataho collective from Aotearoa—New Zealand will present a

large-scale installation in the first room, two other iconics locales in the

exhibition. Queer artists appear throughout the exhibition, and are also the

subject of a large section in the Corderie, which gathers works by artists from

Canada, China, India, Mexico, Pakistan, the Philippines, South Africa, and the

USA, and one devoted to queer abstraction in the Central Pavilion, with works

by artists from China, Italy, and the Philippines. From Europe, three of its

most remarkable female outsider artists are presented: Madge Gill, from the

United Kingdom, Anna Zemánková, from the Czech Republic, and Aloïse, from

Switzerland.

The Nucleo Contemporaneo will feature a special section in

the Corderie devoted to the Disobedience Archive, a project by Marco Scotini,

which since 2005 has been developing a video archive focusing on the

relationships between artistic practices and activism. In the Biennale Arte

2024, the presentation of the Disobedience Archive is designed by Juliana

Ziebell, who also worked in the exhibition architecture of the entire

International Exhibition. The section is divided into

two parts especially conceived for our framework, diaspora activism and gender

disobedience, and will include works by 39 artists and collectives

made between 1975 and 2023.

THE TAKAPAU INSTALLATION BY MATAAHO COLLECTIVE

Te Atiawa Ki Whakarongotai, Ngāti Toa Rangātira, Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Pūkeko, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi, Rangitāne Ki Wairarapa

Founded in Aotearoa, New Zealand, 2012

Based in Aotearoa, New Zealand

The Mataaho Collective, consisting of Māori women artists Bridget Reweti, Erena Baker, Sarah Hudson, and Terri Te Tau, has collaboratively worked for a decade on large-scale fibre-based installations delving into the intricacies of Māori lives and knowledge systems. The term takapau denotes a finely woven mat, traditionally employed in ceremonies, particularly during childbirth. In Te Ao Māori, the womb holds sacred significance as a space where infants connect with the gods. Takapau marks the moment of birth, signifying the transition between light and dark, Te Ao Marama (the realm of light), and Te Ao Atua (the realm of the gods). The tie-downs used in their installation embody a meticulous material selection, serving as tools of security and support for moving cargo, while also being affordable and accessible. This deliberate choice seeks to recognise often-overlooked labourers, emphasising the strength derived from interdependence and honouring a legacy that deserves acknowledgement. The Takapau installation, observable from multiple perspectives, unveils its intricate construction with the interplay of light and shadows on woven patterns offering a multisensorial experience.

This is the first time the work of Mataaho Collective is presented at Biennale Arte.

—Amanda Carneiro

MATAAHO COLLECTIVE

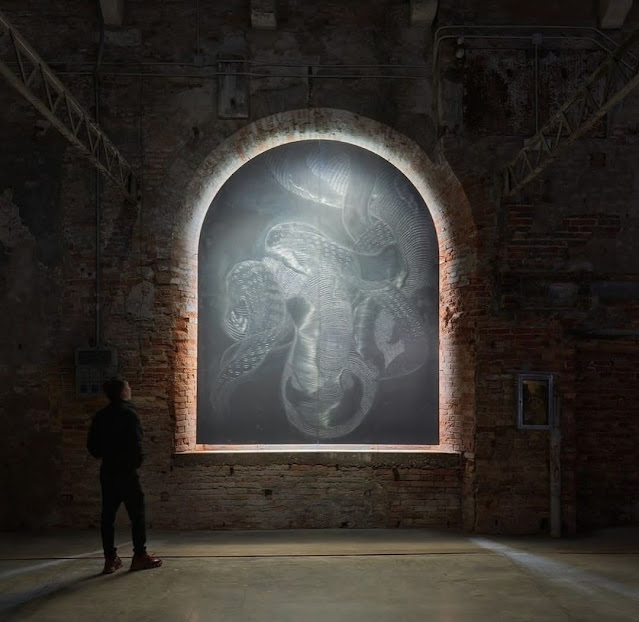

LIPID MUSE BY WANG SHUI

April 20, 2024 – November

24, 2024

Dallas, USA, 1986

Lives in New York, USA

WangShui’s practice is

driven by a desire to dematerialise identity. With the same fluidity, they work

across video, installation, and painting to inhabit shifting states of

materiality and consciousness. Deepening their investigation of liminality,

WangShui presents a newly commissioned installation comprising three

large-scale aluminium paintings and an LED video sculpture. Exploring the

migration of matter and form between Latin America, Asia, and Europe, the

installation builds on the artist’s interest in the transnational interpolation

of form. Each work integrates haptic and mechanical processes to blur the line

between mind and machine. For this new suite of paintings, WangShui manually

anodised aluminium panels with cochineal – a globally traded Mexican red

pigment made by grinding up parasitic insects. The multichannel video sculpture

is assembled with interwoven LED mesh screens, another transmutation of image

and light. The video sculpture’s pulsing lights both attract and disorient its

viewers – the artist’s reminder that consciousness is formed in the latent

spaces between nodes of legibility.

This is the first time

the work of WangShui is presented at Biennale Arte.

—Wong Binghao

BIOGRAPHY CURATOR ADRIANO

PEDROSA

Adriano Pedrosa (Brazil)

has a degree is Law from the Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro and

masters’ degree in Art and Critical Writing from the California Institute of

the Arts. He has published in Arte y Parte (Santander), Artforum (New York), Art

Nexus (Bogotá), Bomb (New York), Exit (Madri), Flash Art (Milan), Frieze

(Londres), Lapiz (Madri), Manifesta Journal (Amstersdã), Mousse (Milano),

Parkett (Zurich), The Exhibitionist (Berlin), among others.

Pedrosa has been the

artistic director of Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand - MASP

since 2014.

Prior to that he was

adjunct curator of the 24th Bienal de São Paulo (1998), curator in charge of

exhibitions and collections at Museu de Arte da Pampulha, Belo Horizonte

(2000-2003), co-curator of the 27th Bienal de São Paulo (2006), curator of

InSite_05 (San Diego Museum of Art, Centro Cultural Tijuana, 2005), artistic

director of the 2nd Trienal de San Juan (2009), curator of 31st Panorama da

Arte Brasileira-Mamõyaguara opá mamõ pupé (Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo,

2009), co-curator of the 12th Istanbul Biennial, and curator of the São Paulo

pavilion at the 9th Shanghai Biennale (2012).

At MASP Pedrosa has

curated many exhibitions, including solo shows dedicated to the work of Tarsila

do Amaral, Anna Bella Geiger, Ione Saldanha, Maria Auxiliadora, Gertrudes

Altschul, Beatriz Milhazes, Wanda Pimentel, and Hélio Oiticia, as well as the

ongoing series devoted to different Histories: Histories of Childhood (2016),

Histories of Sexuality (2017), Afro Atlantic Histories (2018), Women’s

Histories, Feminist Histories (2019), Histories of Dance (2020), Brazilian

Histories (2022).

He is the recipient of

the 2023 Audrey Irmas Award for Curatorial Excellence, given by the Central for

Curatorial Studies at Bard College, New York.

%20copy_1600_1066.jpg)

.png)