BAUHAUS

ARCHIVE' PERMANENT EXHIBITION AT MUSEUM FUR GESTALTUNG

BAUHAUS ARCHIV / MUSEUM FUR GESTALTUNG: PROFILE TEXT

Berlin’s Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung

researches and presents the history and influence of the Bauhaus (1919–1933),

the 20th century’s most important school of architecture, design and art. It

was founded in Darmstadt in 1960 by the art historian Hans Maria Wingler, with

the support of Walter Gropius, the first director of the Bauhaus. Its goal has

always been to provide a new home for the material legacy of the Bauhaus, which

was scattered around the world in 1933. In 1979, after multiple relocations, it

finally moved into the distinctive Berlin building designed by Gropius. The

Bauhaus-Archiv has since continued its work as both a research facility and an

innovative design museum holding the world’s largest collection related to the

Bauhaus. In its permanent exhibition, the BauhausArchiv presents the visionary

character of the Bauhaus as an avant-garde design school: it exhibits student

works created in classes and in the workshops in the fields of architecture,

furniture, ceramics, metalwork, photography, theatre and in the preliminary

course as well as works of the renowned teachers Walter Gropius, Johannes

Itten, Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Vassily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, Oskar

Schlemmer, László Moholy-Nagy and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The

Bauhaus-Archiv’s rich holdings have grown continuously since its foundation –

through purchases, but above all, through donations. Walter Gropius’s donation

of his extensive private archive on the history of the Bauhaus in Weimar and

Dessau still forms the indispensable core of the collection. Important groups

of works by individual artists have entered the collection as bequests,

donations or permanent loans – for example, a substantial part of the oeuvre of

Georg Muche, the artistic estate of Lothar Schreyer, the painted oeuvre of

Bauhaus student Hans Thiemann and the graphic design oeuvre of Herbert Bayer.

In addition to historical topics related to the context of the Bauhaus, the

Bauhaus-Archiv now devotes increasing attention to questions related to

contemporary architecture and current developments in design. To celebrate the

100th anniversary of the Bauhaus’s founding in 2019, the Bauhaus-Archiv will be

receiving a new museum building in the years to come.

Bauhaus Collection In an exhibition space of around

550 square metres, the permanent exhibition “The Bauhaus Collection” provides a

glimpse into the holdings of the largest and most diverse collection related to

the Bauhaus. The entire spectrum of the school’s activity can be seen:

architecture, furniture, ceramics, metal objects, textiles, photography,

advertising, painting, graphic art and theatre. One focus of the exhibition is

on Bauhaus pedagogy. Alongside works by famous teachers, such as Walter

Gropius, Johannes Itten, Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Vassily Kandinsky, Josef

Albers, Oskar Schlemmer, László Moholy-Nagy or Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the

exhibition also presents student works from the preliminary course and the

workshops. Today, products designed by Bauhaus students, such as Marianne

Brandt’s “Bauhausleuchte” (Bauhaus lamp) and Marcel Breuer’s “Wassily Sessel”

(Vassily armchair) are considered classics of modern design.

BAUHAUS – ARCHIV / MUSEUM FUR GESTALTUNG: COLLECTION

& ARCHIVE

The collection of the Bauhaus-Archiv is the world’s

largest and most diverse collection related to the Bauhaus, its history and its

influence. Supported by and with the approval of Bauhaus founder Walter

Gropius, the Bauhaus-Archiv began gathering its Bauhaus collection as early as

1961. It contains works by students and teachers. The holdings of the

collection and archive can be grouped according to the main themes of

“Collection of Graphic Art”, “Workshop Projects: Product Design and Industrial

Design” as well as “Fine-Art Photography”, “Document Collection”, “Photo

Archive” and the research library, with its focus on the Bauhaus. In the permanent exhibition “The

Bauhaus Collection ─ Classic Modern Originals”, the Bauhaus-Archiv uses its

museum space to exhibit essential key works from its collections.

THE COLLECTION OF GRAPHIC ART

The collection of graphic art comprises over 12,000

sheets, consisting of drawings, watercolours, other works on paper and prints

by Bauhaus masters and students. These include the world’s only complete

sequence of all of the cycles and portfolios of prints created by Lyonel

Feininger, Vassily Kandinsky, Gerhard Marcks, László Moholy-Nagy, Georg Muche

and Oskar Schlemmer during the Weimar period as well as each of the “Bauhaus

Prints” series. Many artists are represented by examples of their work before

or after their Bauhaus period, for example, Vassily Kandinsky through early

monochrome woodcuts or Josef Albers and Georg Muche through individual sheets

and series from the 1930s to the 1960s. The collection of graphic art also

includes works of graphic design, such as posters and other printed matter,

advertising designs, typographical designs and also a unique wealth of

materials from every area of education at the Bauhaus: from the preliminary

course of Johannes Itten, Georg Muche, László MoholyNagy and Josef Albers as

well as from the courses of Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Joost Schmidt, Oskar

Schlemmer and Lothar Schreyer. The prehistory of the Bauhaus is documented

through drawings by Adolf Hölzel, studies by his student Lily Hildebrandt from

his classes at the Stuttgart academy and by numerous works created between 1902

and 1912 by Maria Strakosch-Giesler, a student of Kandinsky in Munich. Works

from the successor institutions, the New Bauhaus and the Ulmer Hochschule für

Gestaltung, are also to be found in the collection of graphic works.

The Collection of Workshop Projects: Product Design

and Industrial Design

THE COLLECTION OF WORKSHOP PROJECTS: PRODUCT &

INDUSTRIAL DESIGN

The focus of the collection of workshop projects on

the area of product design and industrial design offers a comprehensive look at

product development at the Bauhaus. In addition to designs, realisations of

products created at the Bauhaus are present in the form of unique objects,

prototypes and examples from their industrial mass production. The extensive

holdings of furniture, lamps, metalwork, ceramics and textiles include design

classics, such as the well-known furniture of Marcel Breuer, the teapot of

Marianne Brandt and the lamp of Wilhelm Wagenfeld.

THE ARCHITECTURAL COLLECTION

The architectural collection comprises around 14,000

sheets, accompanied by numerous architectural models. The most prominent piece

is the original Bauhaus model of 1930. The core of the architectural collection

is formed by 200 works from classes at the Bauhaus. Particularly for the period

under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, these holdings cover every area of teaching –

from technical instruction to the use of ground plans for training

three-dimensional thinking to interior design. The architecture of Walter

Gropius is represented comprehensively in the form of documentary photographs,

which are also supplemented by a selection of drawings and blueprints.

Particular emphasis is to be placed on the holdings related to the Fagus-Werk, the

Bauhaus founder’s early factory design, which was added to the World Heritage

List in 2011. A total of 700 blueprints from the Fagus-Werk archive as well as

photo series by Albert RengerPatzsch, one of the main protagonists of the New

Objectivity in photography, provide a detailed documentation of this early

architectural work by Walter Gropius. In addition, the Bauhaus-Archiv has taken

responsibility for the architectural estates of Wils Ebert, Helmut Heide,

Gustav Hassenpflug, Fritz Kaldenbach, Karl Keller, Franz Singer, Hans Soeder,

Philipp Tolziner, Pius Pahl and Gerhard Weber.

THE COLLECTION OF FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHY

The collection “Fine-Art Photography” comprises a

total of around 6000 prints (including c.4000 vintage prints and 2000 modern

prints) by 117 photographers from the Bauhaus, as well as around 1500 original

negatives taken by Lucia Moholy, Herbert Schürmann and Eugen Batz. The heart of

the collection is formed by fine-art photography from the 1920s and early 1930s

by the Bauhaus teachers László MoholyNagy and Walter Peterhans. The

collection’s spectrum encompasses experiment and snapshot, composition and

portrait, still life and architectural photography. The largest group of works

is formed by the estate of Lucia Moholy, featuring her documentary photographs

of Bauhaus buildings and products. Photographic works by Herbert Beyer,

Marianne Brandt, Erich Consemüller and Pius Pahl as well as by Lyonel, T. Lux

and Andreas Feininger also form a part of the collection. The Bauhaus-Archiv

also holds a collection – the only of its kind in Europe – of around 500

photographs related to the New Bauhaus, including prints by György Kepes,

Nathan Lerner and Henry Holmes Smith.

THE DOCUMENT COLLECTION

The central task of the Bauhaus-Archiv is the

collecting of “all documents related to the activity and the cultural

intellectual heritage of the Bauhaus”. Letters, manuscripts and other written

documents, but also printed texts, are gathered together in the collection of

documents. Walter Gropius’s extensive private archive related to the history of

the Bauhaus during the Weimar and Dessau periods forms the core of the

collection of documents. The complete estates or portions of the estates of

numerous Bauhaus students and staff, such as Georg Muche, Lucia Moholy or Adolf

Behne and Bauhaus-Archiv founder Hans M. Wingler have been added to this, so

that the archival holdings of the document collection has now expanded into a

group of files stretching 140 metres in length. It contains materials dealing

with the prehistory of the Bauhaus and its foundation, an extensive

documentation of the political conflicts surrounding the school, a part of the

minutes of the sessions of the Council of Masters from the years 1919–1923 as

well as documents related to everyday life at the school. A collection of

newspaper cuttings from the years 1917–1934 provides additional information

regarding the history of the Bauhaus’s reception.

THE PHOTO ARCHIVE

With 65,000 photographs, the photo archive of the

Bauhaus-Archiv forms a unique archive of images related to the history of the

Bauhaus and the people, workshops and products involved with it. Consisting

half of originals and half of reproductions, the photo archive material may be

divided up into portrait photos, photographs of student works from classes and

the workshops, the architecture and design of the Bauhaus as well as related

directions. There are 4000 photographs documenting exclusively the person and

work of Walter Gropius. There are also extensive holdings of photographic

material related to the life and work of Bauhaus masters and students, such as

Josef Albers, Herbert Bayer, Marianne Brandt, Marcel Breuer, Adolf Meyer,

Hannes Meyer, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, László Moholy-Nagy, Georg Muche, Oskar

Schlemmer, Joost Schmidt, Franz Singer and Hans Thiemann.

THE LIBRARY

The research library of the Bauhaus-Archiv contains

more than 33,000 items, including secondary literature on the Bauhaus, its

context and also the artists, architects and designers connected with it. This

includes secondary literature on 20th-century art, architecture, photography

and design as well as a generous array of current architecture and design

journals.

COMMERCIAL GRAPHICS

It was Moholy-Nagy who introduced the ideas of the New

Typography to the Bauhaus starting in 1923. From then on, typography began to

play a decisive role in the Bauhaus’s publicity work and in the development of

an unmistakable look for the college. At the Bauhaus in Dessau, Moholy-Nagy’s

student Herbert Bayer took over the workshop for typography and advertising

that was then set up. Within a very short period, he was able to develop it

into a professionally working studio for graphic design that increasingly

received orders from outside the college. From 1928, his successor Joost

Schmidt introduced a systematic course in type design and commercial graphic

design, which he also extended to include the field of exhibition design. This

led to experimental forms of presentation using architecture, sculpture,

photography and typography, which were to decisively shape the image of the

Bauhaus at travelling exhibitions and trade fairs.

JOOST SCHMIDT – DESSAU C. 1930

Letterpress

Dimensions: 23

x 23.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Jan Tschichold Collection, Gift of Philip Johnson

LYONEL FEININGER ( DESIGN ) / OTTO DORFNER (

PRODUCTION ),

BAUHAUS PRINTS. NEW EUROPEAN GRAPHICS. FIRST ISSUE:

MASTER OF THE STAATLICHE BAUHAUS IN WEIMAR

1921

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

Dimensions: 57,5 x 46,5 x 2 cm

© Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin / VG

Bild-Kunst,

Bonn 2015; Foto Markus Hawlik

JOOST SCHMIDT - POSTER FOR THE 1923 BAUHAUS EXHIBITION

1922 - 1923

Lithograph on Paper

Dimensions: 68.6 x 48.3 cm

Collection Merrill C. Berma

MARIANNE BRANDT – TEMPO – TEMPO, PROGRESS, CULTURE 1927

Cut-and-Pasted Newspaper Clippings With Ink

Dimensions: 52 x 39.8 cm

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen

Dresden

LASZLO MOHOLY NAGY – DUST COVER FOR LASZLO MOHOLY –

NAGY

( THE NEW VISION, FROM MATERIAL TO ARCHITECTURE ) 1929

MOSES BAHELFER, BAUHAUS ADVERTISEMENT ‘’ BAUHAUS

TAPETEN ‘’ NO: 5

Finished Artwork / Montage For Printing Plate

Production, 1930

Class of Joost Schmidt, Advertising / Print Workshop

Estate Hannes Meyer, Archiv der Moderne – Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Estate Hannes Meyer, Archiv der Moderne – Klassik Stiftung Weimar

HERBERT BAYER – DESIGN FOR A NEWSPAPER STAND 1924

Tempera and Cut-and-Pasted Print Elements on Paper

Dimensions: 64.5

x 34.5 cm

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

HERBERT BAYER – DESIGN FOR A CIGARETTE PAVILLION 1924

Ink, Tempera, Pencil, and Cut-and-Pasted

Photomechanical

Elements on Cardboard 19

Dimensions: 50.5

x 38 cm

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

HERBERT BAYER – DESIGN FOR A MULTIMEDIA BUILDING 1924

Gouache, Cut-and-Pasted Photomechanical Elements,

Charcoal, Ink, and Pencil on Paper

Dimensions: 54.6

x 46.8 cm

Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of

the Artist

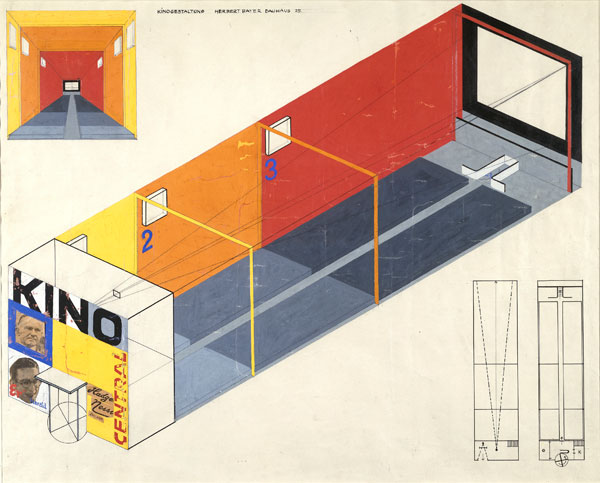

HERBERT BAYER - DESIGN FOR A CINEMA 1924-1925

Gouache, Cut & Pasted Photomechanical and

Print Elements,

Ink, and Pencil on Paper Dimensions: 54.6 x 61 cm

Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of

the Artist

FRIEDL DICKER (?) DRAFT OF A POSTER

" Werkstätten Bildender Kunst G.m.b.H. "

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

HERBERT BAYER – KANDINSKY ZUM 60. GEBURTSTAG 1926

Letterpress and Gravure

Dimensions: 48.2 x 63.5 cm - 48.3 x 63.5 cm

Printer: Bauhausdruck

Credit: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred H. Barr, Jr.

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG

Bild-Kunst, Bonn

OSKAR SCHLEMMER – TWO DESIGNS FOR

THE BAUHAUS SIGNET, 1922

Bauhaus Archive, Berlin

OSKAR SCHLEMMER – POSTER FOR UNREALIZED PERFORMANCE OF

THE TRIADIC

BALLET AT THE LEIBNIZ – AKADEMIE, HANNOVER FEBRUARY 19

AND 26, 1924

Lithograph on Paper

Dimensions: 82.6 x 56.2 cm

Collection Merrill C. Berma

View of the New Presentation of the Bauhaus Collection

Bauhaus-Archiv

HERBERT BAYER - “ SECTION ALLEMANDE ‘’

POSTER FOR THE WERKBUND EXHIBITION IN PARIS 1930

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Photo: Atelier Schneider © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

JOOST SCHMIDT – OFFSET: BOOK & ADVERTISING ART NO:

7

SPECIAL ISSUE ON THE BAUHAUS 1926

Offset on Cardboard

Dimensions: 30.8

x 23.3 cm

Collection Merrill C. Berman

HERBERT BAYER ( COVER DESIGN ) LASZLO MOHOLY – NAGY (

TYPOGRAPHY ),

‘’ STAATLICHES BAUHAUS IN WEIMAR, 1919-1923"

Cover of the Bauhaus Exhibition Catalogue, 1923

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin (4510)

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin (4510)

Print in Red and Black

Dimensions: 25,5 x 26,0 cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2015

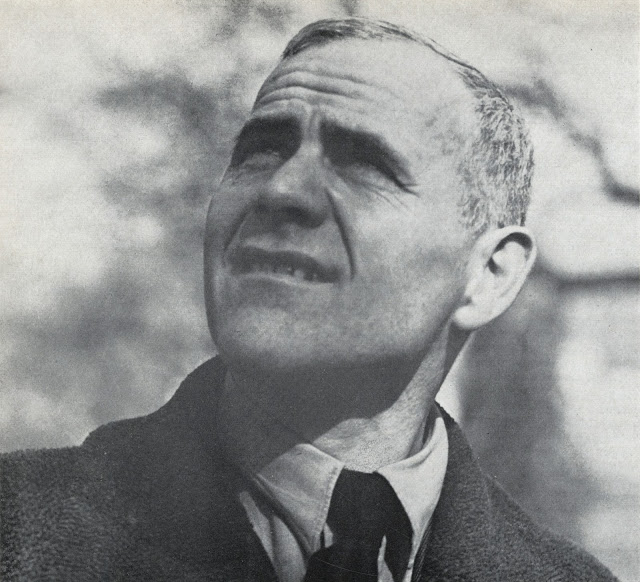

WALTER GROPIUS

‘’ We want to create the purely organic building,

boldly emanating its inner laws, free of untruths or ornamentation.” (Walter

Gropius)

Walter Gropius was the founder of the Bauhaus and

remained committed to the institution that he invested in throughout his life.

He was a Bauhaus impresario in the best possible sense, a combination of

speaker and entrepreneur, a visionary manager who aimed to make art a social

concern during the post-war upheaval. After his departure as the Bauhaus’s

director, Gropius recommended his two successors: Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The conservation

of the Bauhaus’s legacy after its forced closure is another of Gropius’s

accomplishments. He was also able to continue his career in exile in America as

an avant-garde architect.

A native of Berlin, Gropius came from an upper

middle-class background. His great-uncle was the architect Martin Gropius, a

student of Karl Friedrich Schinkel, whose best-known work was the Königliche

Kunstgewerbemuseum (royal museum of applied art) in Berlin, which now bears his

name. In 1908, after studying architecture in Munich and Berlin for four

semesters, Gropius joined the office of the renowned architect and industrial

designer Peter Behrens, who worked as a creative consultant for AEG. Other

members of Behrens's practice included Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Le

Corbusier. Gropius became a member of the Deutscher Werkbund (German Work

Federation) as early as 1910.

The same year, Gropius opened his own company. He

designed furniture, wallpapers, objects for mass production, automobile bodies

and even a diesel locomotive. In 1911, Gropius worked with Adolf Meyer on the design of the Fagus-Werk, a factory in the Lower Saxony

town of Alfeld an der Leine. With its clear cubic form and transparent façade

of steel and glass, this factory building is perceived to be a pioneering work

of what later became known as modern architecture. For the 1914 exhibition of

the Deutscher Werkbund (German Work Federation) in Cologne, Gropius and Adolf

Meyer designed a prototype factory which was to become yet another classic

example of modern architecture.

Gropius served on the Western front in WW I and

experienced this war as a catastrophe. In 1918, he joined the November Group,

which aimed to incorporate the impulses of the revolution in art. From 1919,

Gropius was the head of the Work Council for Art, a radical group of

architects, painters and sculptors. In addition, he contributed to the Gläserne

Kette (crystal chain), a chain letter initiated by Bruno Taut that called for

the "dissolution of the previous foundations" of architecture and the

"disappearance of the personality" of the artist.

With the founding

of the Bauhaus, Gropius was able to translate various ideas from the

radical artists’ associations into reality. As the successor of the Belgian

artist Henry van de Velde, he became the director of the

Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstgewerbeschule (Grand Ducal Saxonian school of

arts and crafts) in Weimar, which he renamed Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar. Gropius

explained the idea of the Bauhaus in the founding Manifesto, a four-page booklet

with the famous Cathedral woodcut by Lyonel Feininger on its cover. The school’s most

innovative educational aspect was its dualistic approach to training in the workshops, which were codirected by a

craftsman (master of works) and an artist (master of form). The crafts-based work was

understood as the ideal unity of artistic design and material production.

According to Gropius’s curriculum,

education at the Bauhaus began with the obligatory preliminary course,

continued in the workshops and culminated in the building. Sommerfeld House in Berlin is considered to be the

first joint endeavour undertaken in the sense of the Bauhaus. It was designed

by Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer (1921/22), and it integrated

furnishings made by the students.

For Gropius the Bauhaus was a laboratory of the arts

where the traditional apprentice and master model was maintained, but where

diverse disciplines were interconnected in a completely new way. The outcome of

this approach was not established from the start but was to be discovered in

the spirit of research and experimentation, which Gropius called “fundamental

research” that was applied to all the disciplines and their products, from the

high-rise to the tea infuser.

In Weimar itself, Gropius left very few traces as an

architect and artist. In 1922, his controversial design for the monument Denkmal der Märzgefallenen was unveiled at Weimar’s main

cemetery. Destroyed by the NSDAP, it was rebuilt after WW II. The director’s

office of the Bauhaus,

which was furnished by Gropius in 1923/24, was also reconstructed.

In 1923, Gropius initiated a change of course at the

Bauhaus with a major exhibition under the motto "Kunst und Technik – Eine

Neue Einheit" (art and technology – a new unity). The school now turned

towards industrial methods of production. As a result, the highly influential

master, Expressionist painter and first director of the preliminary course, Johannes Itten, left the Bauhaus. Gropius

appointed the Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy as his successor.

With the politically motivated move to the industrial

city of Dessau in1925, a new era began for the Bauhaus.

During this period, which is seen as his best and most productive, Gropius

designed not only the Bauhaus Building (opened in 1926) but was also

intensively involved in the development of the large-scale residential building

and the rationalisation of the construction process. The buildings created in

Dessau included the Masters’ Houses (1925/26) that were built for the

Bauhaus masters, the Dessau-Törten housing estate (1926–1928) and the Employment Office.

In 1928,

Walter Gropius – unnerved by the quarrels in local politics about the Bauhaus –

handed the post of director over to the Swiss architect and urbanist Hannes Meyer, whom Gropius had brought to

the Bauhaus the previous year as the head of the newly founded architecture

class. After moving to Berlin, Gropius dedicated himself completely to his

architectural practice and the promotion of New Architecture. The most important

completed buildings of this period include the Dammerstock housing estate in

Karlsruhe (1928/29) and the Siemensstadt housing estate in Berlin (1929/30).

In 1934, Gropius emigrated to England and then on to

the USA in 1937. He worked there as a professor for architecture at the

Graduate School of Design of Harvard University. In 1938, he organised the

exhibition Bauhaus 1919–1928 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York together

with Herbert Bayer. From 1938 to 1941, Gropius maintained an office partnership

with Marcel Breuer. He became an American

citizen in 1944.

In 1946, Gropius founded the young architects’

association The Architects Collaborative (TAC), a manifestation of his

life-long belief in the significance of teamwork, which he had already

successfully introduced at the Bauhaus. One work produced by this office is the

Graduate Center of Harvard University in Cambridge (1949/50).

During the last years of his life, Gropius was once

again frequently active in Berlin. Among other projects, he built a nine-storey

residential building in the Hansa district in 1957 within the scope of the

Interbau exhibition. In 1964/65, Gropius designed plans for the Bauhaus

Archive in Darmstadt.

These were realised in a modified form in Berlin from 1976 to 1979 after

Gropius’s death.

Even beyond his official term as the Bauhaus director

from 1919 to 1928, Gropius was emphatically committed to the recognition and

dissemination of the Bauhaus idea. When he died in 1969 in

Boston, the Bauhaus was at least as famous as its founder.

http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/personen/walter-gropius

ARCHITECTURE

From the very start, the teaching of architecture was

regarded as the highest educational goal in the idea and programme for the

Bauhaus. However, a separate architecture department was only established in

1927 under its second Director, Hannes Meyer. Until then, Gropius had mainly

allowed his students to work on commissions in his own office. His aim was to

have all of the teaching areas collaborating in the ‘building of the future’.

By contrast, Meyer regarded previous Bauhaus work as a purely formal

development whose products had been designed for bourgeois circles. He wanted

to design things for broad sections of the population. The basis for the

architectural training that was provided thus consisted of identifying users’

needs; artistic concerns were made subordinate to this. Finally, under the

third Director, Mies van der Rohe, architecture became the predominant teaching

area. Under the influence of Mies’s own work, aesthetic issues moved strongly

to the fore. Ludwig Hilberseimer balanced this with exercises aimed at

practical aspects. The three Directors of the Bauhaus – all of whom were major

architects – thus each put their own personal stamp on the college’s teaching

work. Consequently, there was never a standard ‘Bauhaus architecture’.

http://www.bauhaus.de/en/ausstellungen/sammlung/211_architektur/

WALTER GROPIUS & ADOLF MEYER ( ARCHITECTS )

HANS WAGNER ( PHOTOGRAPHER )

FAGUS – WERK FACTORY CA. 1911

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin (4699)

BY HANNES MEYER

FARKAS MOLNÁR – PROJECT FOR A SINGLE FAMILY HOUSE (

THE RED CUBE ).

DESIGN FOR A MURAL: THE FABRICATOR / THE CONSUMER 1923

Gouache, Pencil, and Ink on Drawing Paper

Dimensions: 32.6 x 50.2 cm

Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Frankfurt

BAUHAUS DESSAU

View of the New Presentation of the Bauhaus Collection

Bauhaus-Archiv

WALTER GROPIUS ( DESIGN ) – HERBERT BAYER ( DRAWING ),

ISOMETRIC RENDERING OF THE DIRECTOR’S OFFICE IN BAUHAUS WEIMAR 1923

ISOMETRIC RENDERING OF THE DIRECTOR’S OFFICE IN BAUHAUS WEIMAR 1923

WALTER GROPIUS & ADOLF MEYER – CONTRIBUTION TO

THE

COMPETITION FOR THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE OFFICE BUILDING

1922

LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE – ENTRY ‘’ HONEYCOMB ‘’ FOR

THE HIGH-RISE

TOWER AT FRIEDRICHSTRASSE STATION, IDEAS COMPETITION 1922

ALFRED ARNDT – ( MASTERS’ DOUBLE HOUSES, SEEN FROM

BELOW )

COLOR SCHEME FOR THE EXTERIORS 1926

Ink and Tempera on Paper

Dimensions: 76 x 56 cm

© Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

LUCIA MOHOLY ( PHOTO ), WALTER GROPIUS ( ARCHITECT )

MASTERS’ HOUSES, DOUBLE HOUSE NORTWEST SIDE

( KANDINSKY – KLEE ) 1926

Bauhaus Archive, Berlin

JOSEF ALBERS – GRID PICTURE I; ALSO KNOWN AS GLASS

FRAGMENTS IN GRID PICTURE C. 1921

Glass, Wire, and Metal, in Metal Frame

Dimensions: 39 x 33.3 cm

The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Conn

JOSEF ALBERS WALL DETAIL 1949-50

METALL

WORKSHOPS

Sphere,

circle and cross: this is one of the best-known works produced at the Bauhaus.

Marianne

Brandt already created this tea infuser at the end of her first year of studies

in the Metals Workshop. In programmatic terms, it is constructed from

elementary shapes typical of the Weimar period: the body of the vessel consists

of a hemisphere, and the handle is a segment of a circle. Instead of the

traditional ringed base, it sits on a cross, which emphasizes the pot’s main

axes and also gives it a certain quality of weightlessness.

The

pot, only 7.5 cm high, thus looks like a sculptural implementation of

compositions by László Moholy-Nagy, who headed the Metals Workshop at the

Bauhaus from 1923 to 1928. His aim was to make the former ‘Gold-, Silver- and

Coppersmiths’ Workshop’ more industrial and he was open to materials such as

nickel and glass, which did not traditionally belong in the field. This made

possible, for example, the creation of the legendary Bauhaus Lamp by Carl Jakob

Jucker and Wilhelm Wagenfeld. Like several other products of the Weimar period,

however, it was to remain an expensive hand-made item. In Dessau, the Metals

Workshop then became a regular design laboratory for new lighting fixtures.

After several lamp manufacturers had put the models into serial production, the

Metals Workshop ultimately became one of the most productive and successful

workshops at the Bauhaus.

MARIANNE BRANDT, TEA INFUSER (MT 49), 1924

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Photo: Gunter Lepkowski © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

MARIANNE BRANDT ( DESIGN ) – LUCIA MOHOLY ( PHOTO )

COFFEE & TEA SET 1924

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

PHOTOGRAPHY

In 1923, Moholy-Nagy provided the decisive impetus

that led to the Bauhaus’s engagement with photography.

László Moholy-Nagy introduced the ‘New Seeing’ to the

Bauhaus in Dessau. His photographs of the Dessau Bauhaus building, for example,

are in no sense mechanical reproductions of reality. Instead, they approach it

actively using unconventional and even daring perspectives – and thus define a

new relationship between people and architecture. The progressive sense of life

this expressed was quickly taken up by other Bauhaus photographers. Their

photos reflect the life, utopianism and spirit of fresh departures of a new

era. Not least through his photograms, collages and multiple-exposure shots,

Moholy-Nagy inspired the Bauhaus members to a new way of looking that provided

the basis for experimentally exploring and making use of the medium’s potential.

Before this, photography had only played a minor role.

Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius used it mainly for purposes of documentation and

publicity for the objects and architecture developed at the Bauhaus. Lucia

Moholy became the official documentary photographer and despite the objectivity

required she soon developed her own quite individual style of depiction. A

separate photography course was only introduced in 1929, as a special

department of the Typography and Advertising Workshop. It was headed by Walter

Peterhans, who taught the students not only photographic theory and practice,

but also how to see with precision. The shapes and textures of the arranged

objects were now captured down to their last nuances using meticulous lighting

and given an almost magical effect. This emphasis on technical perfection was

owed not least to the development of new professional specialties in commercial

and applied photography. It ended the experimental phase of photography at the

Bauhaus, with institutionalized teaching taking its place.

KURT SCHWERDTFEGER, REFLECTING LIGHT GAMES, 1922 -

1923

Bauhaus University Weimar, Archiv der

Moderne (BA XI/9)

Bauhaus University Weimar, Archiv der

Moderne (BA XI/9)

Photo: Fotoatelier Hüttich & Oemler, Weimar

© Bauhaus University Weimar, Archiv der Moderne

EDMUND COLLEIN – EXTENSION TO THE PRELLERHAUS. FROM 9

YEARS BAUHAUS:

A CHRONICLE, A SET OF WORKS MADE FOR WALTER GROPIUS ON

HIS DEPARTURE FROM THE SCHOOL 1928

Cut-and-Pasted Photographs and Photomechanical

Reproductions,

With and Written Stickers on Paper

Dimensions: 41.5 x 55 cm

© Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

EDMUND COLLEIN – EXTENSION TO THE PRELLERHAUS. FROM 9 YEARS BAUHAUS:

A CHRONICLE, A SET OF WORKS MADE FOR WALTER GROPIUS ON

HIS DEPARTURE FROM THE SCHOOL 1928 ( DETAIL )

HERBERT BAYER – IRON WINDING STAIR 1928

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 35.6 x 24.4 cm

Credit: Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG

Bild-Kunst, Bonn

LASZLO MOHOLY NAGY – BERLIN, RADIO TOWER 1928

Gelatin silver print

Dimensions: 38.1 x 27.8 cm

Credit: Thomas Walther Collection. Gift of Thomas

Walther

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG

Bild-Kunst, Bonn

HERBERT BAYER – LONELY METROPOLITAN 1932

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: Image: 26.8 x 34 cm, Frame: 47 x 57.2

cm

Classification: Photographs

Credit Line: Herbert Bayer Collection and Archive,

Denver Art Museum,

Gift of BP Corporation

ELSA THIEMANN, FORKS C. 1930

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

© Margot Schmidt

HEINZ LOEW ( CONSTRUCTION ) / EDMUND COLLEIN (

PHOTOGRAPHS ), FROM

LINE & CIRCLE ( ROD AND RING ) TO HYPERBOLOID AND

SPHERE C.1930

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Photo: Markus Hawlik

© Ursula Kirsten-Collein / Irmgard Loew

© Ursula Kirsten-Collein / Irmgard Loew

KURT KRANZ, BUTTON EYE 1970

Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

Photo: Uwe Jacobshagen

© Ingrid Kranz

© Ingrid Kranz

KURT KRANZ – THE SINKING ONES 1931

Cut & Pasted Gelatin Silver Prints & Photomechanical

Reproductions on Paper 19

Dimensions: 50 x 63 cm

Galerie Berinson, Berlin

JOOST SCHMIDT – COVER OF THE FUTURE BELONGS TO BAUHAUS

WALLPAPER 1931

Letterpress on Paper ( With Cut-Outs )

Dimensions: 14.8

x 21 cm

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

OSKAR SCHLEMMER

IRENE BAYER, ANDOR WEININGER DRESSED AS A CLOWN C.1927

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

© Unknown

MARIANNE BRANDT – OUR UNNERVING CITY 1926

Cut-and-Pasted Newspaper Clippings on Gray Cardboard

Dimensions: 63.5 x 48.6 cm

Private collection, Chicago

HERBERT BAYER

– HUMANLY IMPOSSIBLE 1932

Gelatin Silver

Print

Dimensions:

38.9 x 29.3 cm

Credit: Thomas

Walther Collection. Acquired through the generosity of Howard Stein

© 2016 Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

WALTER PETERHANS – OPHELIA

( STILL LIFE WITH LEMON SLICE, TULLE AND FEATHERS ) C.

1929

View of the New Presentation of the Bauhaus Collection

Bauhaus-Archiv, Photo: Hans Glave

LUCIA MOHOLY NAGY – UNTITLED ( LASZLO MOHOLY –

NAGY ) 1925-1926

Gelatin Silver Print, Probably Printed 1928-30

Dimensions: 25.6

x 20 cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ford Motor

Company Collection,

Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell

THEATRE

Oskar

Schlemmer described his Triadic Ballet as a ‘party in form and colour’. Form,

colour and abstraction began to define the way in which the human figure was

depicted in the work of painter and sculptor Oskar Schlemmer from an early

stage. The Triadic Ballet was his first major theatrical work, already created

in Stuttgart in 1922 before his time at the Bauhaus. Here again, he reduced the

human figure to basic geometric shapes: abstract costumes made of rigid,

movement-inhibiting pieces determined the peculiar quality of the ‘ballet’.

Schlemmer regarded the work as a form of ‘artistic metaphysical mathematics’.

In three dance sequences, he intensified the drama from humorous and farcical

to mystical and heroic qualities, without following any specific plot.

Schlemmer’s Ballet thus became an anti-dance, a kind of ‘choreographic

constructivism’ – and was extremely successful at its first performance at the

Bauhaus in 1923.

OSKAR SCHLEMMER – COSTUME DESIGNS FOR THE TRIADIC BALLET 1926

Ink, Gouache, Metallic Powder, and Pencil, With Adhered

Typewritten Elements on Paper, Mounted on Card

Dimensions: 38.6 x 53.7 cm

Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Museum Purchase

OSKAR SCHLEMMER – GROUP PHOTO OF TRIADISCHES BALLETT

1927

OSKAR SCHLEMMER 1922

OSKAR SCHLEMMER – STUDY FOR ‘’ THE TRIADIC BALLET ‘’ C. 1924

Gouache, Ink, and Cut-and-Pasted Gelatin Silver Prints on Black Paper

Dimensions: 57.5 x 37.1 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Lily Auchincloss

EBERHARD SCHRAMMEN, MASCOT C. 1924,

Oak and Miscellaneous Exotic Woods, Turned, Coated in

Places With Colored and Gold Lacquer,

Dimensions: Height: 14-9/16

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Photo: Gunter Lepkowski, ©

Estate Eberhard Schrammen

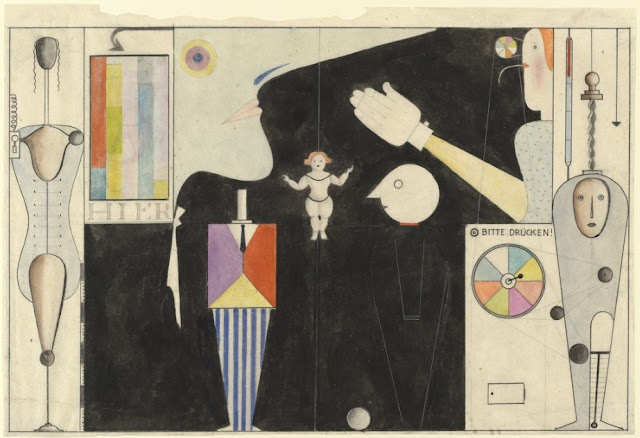

OSKAR SCHLEMMER – THE FIGURAL CABINET 1922

Watercolor, Pencil, and Ink on Tracing Paper

Dimensions: 30.8

x 45.1 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Joan and

Lester Avnet Collection

BAUHAUS ARCHIV - MUSEUM FUR GESTALTUNG

BAUHAUS ARCHIV - MUSEUM FUR GESTALTUNG

The building is the largest exhibition facility at the

Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung, and was designed by the first Director

of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius. Planning for it began in 1964 for a site in

Darmstadt, but a modified version of it was then built in Berlin in 1976–1979.

Gropius’s former employee Alex Cvijanovic carried out the replanning needed,

along with Berlin architect Hans Bandel. Although the adaptation process proved

to be difficult and time-consuming and was affected by political and financial

problems, the building’s memorable silhouette with the shed roofs survived,

along with the general ground plan arrangements designed by Gropius. The

building was listed as a protected monument in 1997 and it is today one of

Berlin’s landmarks.

The relative alteration in the status of the

Bauhaus-Archiv in the centre of the city that followed the fall of the Berlin

Wall in 1989 led to new challenges. Rapidly increasing numbers of visitors are

a sign of the tremendous – and international – interest in the institution,

which only has 700 square metres of exhibition space available. The aim is to

supplement the building with a new building in Klingelhöferstrasse in time for

the centenary of the founding of the Bauhaus in 2019.

NEW BUILDING PROJECT

In 2019, the Federal Republic of Germany will be

celebrating the centenary of the founding of the Bauhaus, the twentieth

century’s most important college of architecture and design. To coincide with

the Bauhaus anniversary, the Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung in Berlin

is to be given the spatial facilities it needs to meet the requirements of

running a museum and archive in the 21st century. The existing building,

designed by Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, is to be renovated in accordance

with historic monument requirements and will be extended with the addition of a

new building. The Bauhaus-Archiv/Museum für Gestaltung holds the world’s most

extensive collection of materials on the history of the Bauhaus. The building,

opened in 1979, has now become too small and is no longer able to do justice to

the increased demands on a museum that also serves as an archive. Visitor

numbers have doubled during the last 10 years; in 2014, a total of 115,000

people interested in the Bauhaus visited the building. In the future, the

functions of the Bauhaus-Archiv/Museum für Gestaltung are to be distributed

across two buildings. The intention is to use the existing building for the

archive, while the annexe building will be used as the museum.

http://www.bauhaus.de/en/neubau/

MANIFESTO BY WALTER GROPIUS APRIL 1919

“The ultimate goal of all art is the building!

The ornamentation of the building was once the main purpose of the visual arts,

and they were considered indispensable parts of the great building. Today, they

exist in complacent isolation, from which they can only be salvaged by the

purposeful and cooperative endeavours of all artisans. Architects, painters and

sculptors must learn a new way of seeing and understanding the composite

character of the building, both as a totality and in terms of its parts. Their

work will then re-imbue itself with the spirit of architecture, which it lost

in salon art.

The art schools of old were incapable of producing

this unity – and how could they, for art may not be taught. They must return to

the workshop. This world of mere drawing and painting of draughtsmen and

applied artists must at long last become a world that builds. When a young

person who senses within himself a love for creative endeavour begins his

career, as in the past, by learning a trade, the unproductive “artist” will no

longer be condemned to the imperfect practice of art because his skill is now

preserved in craftsmanship, where he may achieve excellence.

Architects, sculptors, painters – we all must return

to craftsmanship! For there is no such thing as “art by profession”. There is

no essential difference between the artist and the artisan. The artist is an

exalted artisan. Merciful heaven, in rare moments of illumination beyond man’s

will, may allow art to blossom from the work of his hand, but the foundations

of proficiency are indispensable to every artist. This is the original source

of creative design.

So let us therefore create a new guild of craftsmen,

free of the divisive class pretensions that endeavoured to raise a prideful

barrier between craftsmen and artists! Let us strive for, conceive and create

the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture

and sculpture and painting, and which will one day rise heavenwards from the

million hands of craftsmen as a clear symbol of a new belief to come."

http://www.bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/das-bauhaus/idee/manifest

BAUHAUS ARCHIV - MUSEUM FUR GESTALTUNG

TEXTILES

It was mainly women who completed their training in

the Textiles Workshop – partly because the Bauhaus Council of Masters reserved

the few other workshop places for allegedly better-suited men. Gunta Stölzl

headed the workshop starting in 1927, as the successor to Itten and Muche. She

developed an eight-semester training course which from 1929 onwards could be

completed with a Bauhaus Diploma. She divided the course work into two areas:

‘Developing Basic Materials for Interior Decoration (Types for Industry)’, and

‘Speculative Examination of Materials, Form, and Colour in Gobelin and

Tapestry’. By contrast, Stölzl’s successors Lilly Reich and Otti Berger focused

from 1931 onwards on stronger collaboration with industry. However, the three

textile pattern-books published during the last two years of the Bauhaus came

too late for profitable industrial manufacturing to be achieved.

GUNTA STOLZL RED GREEN SLIT TAPESTRY 1927-1928

ANNI ALBERS – PIANO CIVER OR TAPESTRY ( YELLOW )

WE 493/445, 1926 ( NEW WEAVING OF 1964)

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Photo: Gunter Lepkowski © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

View of the New Presentation of the Bauhaus Collection

Bauhaus-Archiv

ANNI ALBERS 1926-1964

OTTI BERGER ( TOUCH PANEL ) MADE FOR PRELIMINARY

COURSE TAUGHT

BY LASZLO MOHOLY NAGY 1928

Threads and Board on Wire Backing With Loosely Attached

Multicolored Square Paper Cards

Dimensions: 14 x 57 cm

© Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

FURNITURE

By his own account, it was bicycle handlebars that

inspired Breuer to create his tubular steel chair.

Marcel Breuer headed the Furniture Workshop at the

Bauhaus from 1925 to 1928. During that time, he designed the first tubular

steel chair in the history of design: the B3 chair (later also known as

Wassily). Up to that time, steel tubing had mainly been used for hospital

furniture. Breuer developed it into a ‘club chair’ for the living-room – not

the kind of heavy, upholstered chair previously seen, but a light seat designed

for industrial production. Although it was some time before industrial

manufacturing of the tubular steel armchair followed and the later versions

were welded and inserted, making them difficult to dismantle, its open

construction reduced to only a few elements perfectly matched the Bauhaus’s

functional aesthetic.

The Furniture Workshop was thus one of the first

workshops to accept the need for standardization for the purposes of industrial

production. After Breuer had left the Bauhaus, its character shifted more

strongly under Hannes Meyer towards furniture that had been developed to

production stage and towards multifunctional furniture items made of simple

materials, such as Josef Pohl’s so-called ‘Bachelor’s Wardrobe’. ‘People’s

necessities, not luxuries’ [‘Volksbedarf statt Luxusbedarf’] was now the motto,

after the tubular steel furniture had become fashionable among intellectuals.

Under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, finally, the workshop was attached to the

Interior Finishing department – partly because the link between production

operations and college work appeared contradictory to him. In fact, many of the

famous classics of modernism that are today regarded as ‘Bauhaus models’ were

created outside of college work. However, none of the workshops shaped the

image of the Bauhaus as much as the Furniture Workshop did.

GERRIT RIETVELD – RED BLUE CHAIR C. 1923

Painted Wood

Dimensions: 86.7 x 66 x 83.8 cm, Seat h. 33 cm

Credit: Gift of Philip Johnson

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York /

Beeldrecht, Amsterdam

GERRIT

RIETVELD – RED BLUE CHAIR C. 1923

In the

Red Blue Chair, Rietveld manipulated rectilinear volumes and examined the

interaction of vertical and horizontal planes, much as he did in his

architecture. Although the chair was originally designed in 1918, its color

scheme of primary colors (red, yellow, blue) plus black—so closely associated

with the de Stijl group and its most famous theorist and practitioner Piet

Mondrian—was applied to it around 1923. Hoping that much of his furniture would

eventually be mass-produced rather than handcrafted, Rietveld aimed for

simplicity in construction. The pieces of wood that comprise the Red Blue Chair

are in the standard lumber sizes readily available at the time.

Rietveld

believed there was a greater goal for the furniture designer than just physical

comfort: the well-being and comfort of the spirit. Rietveld and his colleagues

in the de Stijl art and architecture movement sought to create a utopia based

on a harmonic human-made order, which they believed could renew Europe after

the devastating turmoil of World War I. New forms, in their view, were

essential to this rebuilding.

MARCEL BREUER – WASSILY CHAIR / 1927 - 1928

Dimensions: 28-1/4 x 30-3/4 x 28"

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Herbert

Bayer

MARCEL BREUER – WASSILY CHAIR / 1927 - 1928

PETER KELER – WIEGE 1922

Weimar Classics Foundation

MARCEL BREUER – CHILDREN’S CHAIR, DESIGN 1924

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Photo: Fotostudio Bartsch

MARCEL BREUER & GUNTA STÖLZL - "AFRICAN" OR "ROMANTIC" CHAIR 1921

Oak and Cherrywood Painted With Water-Soluble Color,

and Brocade

of Gold, Hemp, Wool, Cotton, Silk, and Other Fabric

Threads,

Interwoven by Various Techniques With Twined

Hemp Ground

Dimensions: 179.4

x 65 x 67.1 cm

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Acquired with Funds Provided by

Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung

JOSEF ALBERS - ARMCHAIR DESIGNED 1926

This Example Produced 1928 Solid Mahogany and

Mahogany Veneer on Beech, Solid

Maple, Upholstery on Beech Frame, and

Nickel-Plated Slotted Screws With Round Heads

Dimensions: 61.6 x 67.6 cm

© Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

JOSEF ALBERS SET OF STACKING TABLES C. 1927

JOSEF ALBERS - ARMCHAIR DESIGNED 1926

View of the New Presentation of the Bauhaus Collection

Bauhaus-Archiv, Photo: Hans Glave

BARCELONA CHAIR 1929 BY LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE

BARCELONA CHAIR 1929 BY LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE

ZIG ZAG CHAIR BY GERRIT RIETVELD

ZIG ZAG CHAIR BY GERRIT RIETVELD

CERAMICS

The Ceramics Workshop only existed during the Weimar

period. Located 30 km (18 miles) away from the Bauhaus in the little town of

Dornburg, it was still being set up when Bogler started his training there

together with Otto Lindig in 1920. Lindig’s work in particular shows an

engagement with sculptural form that is typical for this early period. Max

Krehan trained the students in craft aspects, Gerhard Marcks was responsible

for their artistic training and encouraged his students to treat the individual

components of the vessels in a free and combinatory way. This delight in

experimentation had a formative influence on them; after the workshop was

closed in 1925, inspiration from Dornburg continued to influence the potters

who had been trained there. The workshop, which only existed for five years,

thus became a nucleus for the development of twentieth-century ceramics.

THEODOR BOGLER – COMBINATION TEAPOT

WITH BRAIDED METAL

HANDLE (L6) 1923

GERHARD MARCKS – STOVE TILE WITH

A PORTRAIT OF OTTO LINDIG CA. 1921

Weimar Classics Foundation

HANNES MEYER

‘’ Building is just organisation: social, technical,

economic and physical organisation.”

Hannes Meyer

Hannes Meyer was one of the most important architects

of New Architecture movement of the 1920s. During his brief term in office as

the second Bauhaus director, he gave the institution new impulses that had a

lasting influence on important aspects of the Bauhaus’s reception and animated

the topical debates. His theory, which emphasised the social aspects of design,

was widely criticised and poorly received.

Hannes Meyer, the son of an architect, began his

architectural career in 1905 with training as a mason and construction

draughtsman in Basel. He also attended construction courses at the vocational

school there. This was followed by sojourns in Berlin, staying with the

architects Albert Fröhlich and Johann Emil Schaudt. He then studied housing

construction in the English town of Bath. In 1916, he became the office manager

for the Munich architect Georg Metzendorf, for whom he worked on the planning

of the Krupp Margarethenhöhe housing estate in Essen.

From 1919, Hannes Meyer headed his own architecture

office in Basel. Based on his plans, the Freidorf communal housing estate near

Muttenz was built from 1919 to 1921. In 1924, he joined the Basel group

associated with the magazine ABC Beiträge zum Bauen ( ABC contributions to

building). Mart

Stam, El Lissitzky and Hans Schmidt also belonged to this group.

Together with Hans Wittwer, with whom he later built the ADGB school ( Federal School for the German Trade

Unions ) in Bernau near Berlin, he experimented in 1926/27 with constructivist

forms and functionalist methods. These also formed the basis for their

competition designs for the Petersschule ( St. Peter’s school ) in Basel and

the League of Nations Building in Geneva, neither of which was

actually built.

In 1927,

Hannes Meyer arrived at the Bauhaus Dessau with his business partner Hans Wittwer

and assumed a post as director of the newly established building department. On

1st April 1928, Walter Gropius appointed him to be his successor as

the director of the Bauhaus. Despite reaching a broad conceptual consensus –

for both of them, building meant the “ organisation of life processes ” –

Hannes Meyer moved away from artistic intuition towards building theory. He

separated the sciences from the arts and introduced new subjects related to

technology, natural science and the humanities. He also reorganised the

workshops to meet the requirements of industry and an egalitarian social ideal.

An important goal for Meyer was to “ curtail the influence of the artist ”.

Starting in the winter semester of 1927/28, the school offered free painting

classes. The Bauhaus now aspired to two educational objectives: to educate the

production or construction engineer and the artist. Instead of Gropius’s

“exploration of the principles of design”, Meyer called on the students to base

their designs strictly on the given requirements and to study the “life processes”

of the future users. He promoted the expansion of the workshops on a

cooperative basis and set up vertical brigades that united the students of

various academic years in the implementation of projects such as the ADGB school building. The curriculum now

included photography ( in a photography workshop which was part of the

advertising department ) and lessons in urban planning.

For Hannes Meyer, building, as the design of the human

environment, was “based on society”. The goal, the “ harmonious organisation of

our society ”, was therefore to be achieved through “ life-supporting design ”.

Meyer represented the standpoint that the Bauhaus had abandoned its idea of

designing “ for the people ”: most of the Bauhaus products were already

expensive and therefore reserved for an exclusive group of buyers. As a result,

Meyer‘s new slogan was: “ The people’s needs instead of the need for luxury! ”

In his urban development plans, Hannes Meyer was

committed to the cooperative movement and called himself a Marxist. From 1928

to 1930, he built the school building for the ADGB in Bernau near Berlin and

the Nolden House in the Eifel region in 1928. From 1929 to 1930, he extended

the Dessau-Törten housing estate designed by Gropius with the Laubenganghäuser ( Balcony Access Houses ).

Meyer’s continued critique of the direction in which

the Bauhaus had developed caused increasing tensions with Walter Gropius, who

had lost nothing of his power base even after his resignation. In addition, the

Bauhaus’s students became increasingly politicised and radicalised as the

communist influence grew. Because Meyer did not prohibit these tendencies in

his role as director, Gropius – together with the Lord Mayor of Dessau, Fritz

Hesse, and Bauhaus teachers such as Wassily Kandinsky – ultimately pleaded to have Meyers

fired in order to protect the school from political repercussions. On 1st

August 1930, Meyer was dismissed summarily by the city of Dessau due to “

Communist machinations ”. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who had also been

recommended by Gropius, became his successor as director.

As early as 1930, Meyer emigrated to the Soviet Union

with a group of former Bauhaus students. In the same year, he taught at WASI,

an academy for architecture and civil engineering, in Moscow. In the following

years, he also acted as an advisor for urban development projects at Giprogor,

the Russian Institute for Urban and Investment Development. From 1932, he

participated in the Standardgor Project and was the director of the scientific

committee for residential and public buildings at the academy of architecture

founded in 1934. Among other things, Hannes Meyer designed plans for universities

and academies, for the development of “ Greater Moscow ” and for settlements in

the Far East. On lecture tours in Europe, which took him to Germany,

Czechoslovakia, Sweden, Switzerland and other countries, he reported on urban

development and architectural projects in the Soviet Union and discussed what

he believed to be the great perspectives that were opening up there for

architects. Hannes Meyer actively participated in the discourse that began in

1929 on the suppression of the “ bourgeoisie ” concept in architecture and

revised some of his radical theoretical approaches, coming more into line with

the concept of socialist realism. In the course of the Stalinist purges, to

which some of the Bauhaus’s members also fell victim, Meyer returned to Switzerland

in 1936. In 1937, the cooperative children’s holiday home Mümliswil was built

under his direction.

In 1939, Hannes Meyer was appointed by the Mexican

government as the director of the newly founded Institute for Urban Development

and Planning at the National Polytechnic Institute in Mexico City. For

political reasons, Hannes Meyer was dismissed from this post in 1941. Hannes

Meyer designed plans for residential homes and developments, for hospital

developments and schools. He supported working groups of artists such as the

Taler de Grafica Popular (TGP), organised exhibitions and dedicated himself to

the few building contracts that he acquired.

In 1949, he returned to Europe. His hopes of

participating in the reconstruction of the war-torn cities were dashed, and he

returned to his homeland of Switzerland, where he was unable to realise any

further projects.

Hannes Meyer, who is also referred to as the “ unknown

Bauhaus director ”, was always too Communist for some and too bourgeois for

others. Only in retrospect does it become clear that he probably had a stronger

influence on the Bauhaus than Gropius may have wanted to believe.

Literature:

Merten, Britta: Der Architekt Hannes Meyer und sein Beitrag zum Bauhaus. Ein Vergleich mit Walter Gropius und Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008;

Verein Baudenkmal Bundesschule Bernau e.V. (Hg.): Weltkulturerbe vor den Toren Berlins. Hannes Meyer (1889-1954), Bernau 2004.

Merten, Britta: Der Architekt Hannes Meyer und sein Beitrag zum Bauhaus. Ein Vergleich mit Walter Gropius und Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008;

Verein Baudenkmal Bundesschule Bernau e.V. (Hg.): Weltkulturerbe vor den Toren Berlins. Hannes Meyer (1889-1954), Bernau 2004.

http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/personen/hannes-meyer

SCULPTURE

This is the only stone sculpture that has survived

from the sculpture workshop. Otto Werner’s work has the programmatic title

Construction Sculpture: its blocky structure with a complex spatial layering of

individual cubic shapes is borrowed from the New Architecture advocated by the

Bauhaus and others. At the same time, Werner’s abstract sculpture also suggests

associations with a human figure. The models for it were sculptures and reliefs

by Oskar Schlemmer that work with overlays of architectural and figurative

elements.

Schlemmer succeeded Johannes Itten as Form Master in

the sculpture workshops for wood and stone in 1922. In the following period,

the two workshops departed from their programmatic focus on architecture. Due

to a lack of actual commissions from the field of architectural sculpture, free

sculptural works were increasingly produced. When the Bauhaus moved to Dessau,

a reorientation took place; in the ‘Sculpture Workshop’ established in 1925

under Joost Schmidt, elementary training in sculpture was given that had

parallels in the teaching work of Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. The aim was

to ‘arouse, develop and intensify the spatial imagination, conscious experience

of spatial sense perceptions and implementation of spatial ideas’, as one of

the students, Heinz Loew, described it. Practical applications were available

in the areas of stage design, model-making and exhibition architecture.

OSKAR SCHLEMMER, FREE SCULPTURE G, DESIGN 1921– 1923,

CAST 1963

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Photo: Gunter Lepkowski

View of the New Presentation of the Bauhaus Collection

Bauhaus-Archiv

OSCAR SCHLEMMER – ARCHITECTURAL SCULPTURE R, 1919

OSKAR SCHLEMMER & JOSEF HARTWIG - GROTESK I

- 1923

Walnut and Ivory, With Metal Shaft

Dimensions: 56

x 23.5 x 10 cm

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Neue Nationalgalerie,

Berlin

ILSE FEHLING, DESIGN OF A FIGURINE FOR THE MARIONETTE

PLAY

‘’ FIVE WANDERERS BETWEEN THE WORLDS ), 1922

Bauhaus-Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

Bauhaus-Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

© Gaby Fehling, Munich

OTTO WERNER – ARCHITECTURAL SCULPTURE 1922

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Photo: Markus Hawlik © Hansgeorg Werner

TEACHING

During the Bauhaus’s teaching work, a very wide

variety of pieces were thus produced that approached the subject of design in

new and independent ways. The aim of the courses was to produce a universal

designer who would be able to work creatively in architecture, craft work or

industry. Courses given by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee

supplemented the Preliminary Course. In ‘Analytic Drawing’ and in Kandinsky’s

courses on colour, the students addressed questions of composition, abstraction

and colour; with Klee, they engaged with colour, line and form. From the very

start, the majority of the students also did exercises in painting and drawing.

Kandinsky regarded free artistic analysis, particularly in painting, as acting

as a ‘force helping to organize’ students on their way to becoming designers.

The extent to which the students were free to choose their own means of

artistic expression is evident from the astonishing stylistic breadth of the works

produced.

BALANCE STUDY FROM LASZLO MOHOLY NAGY’S

PRELIMINARY COURSE, UM 1924 ( REPLICA 1967 )

LOTHAR SCHREYER OR STUDENT FROM HIS CLASS, BAUHAUS

WEIMAR CURRICULUM FOR WINTER SEMESTER OF 1921- 1922

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin (9077)

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin (9077)

Aquarell, Tempera und Tusche, Uber

Bleistiftvorzeichnung,

Dimensions: 16,5 x 33 cm, halbkreisförmig

© Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

PAUL KLEE COLOUR CHART 1931

EXERCISE FROM PAUL KLEE’S COLOUR CLASS 1925

Karl Peter Röhl Foundation, Weimar

MOSES MIRKIN ( DESIGN ), ALFRED ARNDT ( RECONSTRUCTION ),

CONTRAST STUDY IN VARIOUS MATERIALS 1920,

RECONSTRUCTION 1967

WALTER GROPIUS, SCHEMA ZUM AUFBAU DER LEHRE AM BAUHAUS

1922,

VEROFFENTLICHT IN: STAATLICHES BAUHAUS WEIMAR,

1919-1923

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2013

ALFRED ARNDT, COLOUR CIRCLE FROM GERTRUD GRUNOW’S

COURSE, CA. 1921

Water Colour, Tusche, Pencil and Silver Paper

Assembled on Brown Hand-Made Paper

Dimensions: 52,6 x 45,5 cm

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2015

PAINTING

It was no accident that Walter Gropius appointed

artists as lecturers at the Bauhaus: he regarded the creative potential of

avant-garde art as a basis for living, forward-looking work at his new college.

He hoped through this to ‘stimulate the students from two sides … from the

artistic side, on the one hand, and from the craft side on the other’. The

artists thus worked as so-called ‘form masters’ in the workshops, which they

were in charge of along with the ‘work masters’ – trained crafts specialists. In

addition, they were able on their own initiative to explore new ways of

teaching the foundations of art. They were responsible for giving the

preliminary course – as did Johannes Itten, George Muche and László Moholy-Nagy

– or developed their own individual course topics and teaching methods, as did

Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Oskar Schlemmer. The courses also influenced

their own artistic work. Pure painting classes were only introduced during the

late Dessau period; in Weimar and in the early years in Dessau, the Bauhaus

wanted to finally leave behind that type of academic teaching structure and

follow new, more integrated paths in art training.

JOHANNES ITTEN, COLOUR SPHERE IN 7 LIGHT VALUES AND 12

TONES IN:

BRUNO ADLER, UTOPIA. DOKUMENTE DER WIRKLICHKEIT, WEIMAR 1921

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin (10741)

BRUNO ADLER, UTOPIA. DOKUMENTE DER WIRKLICHKEIT, WEIMAR 1921

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin (10741)

Lithograph on Cardboard

Dimensions: 47,3 x 32,2 cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2015

PAUL KLEE – SOLUTION ‘’EE’’ FOR THE BIRTHDAY TASK,

FROM THE PORTFOLIO FOR WALTER GROPIUS 1924

PETER KELER – DE STIJL 1, 1922

Weimar Classics Foundation

WASSILY KANDINSKY, KLEINE WELTEN, 1922

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin (258/1-2)

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin (258/1-2)

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2015

WASSILY KANDINSKY, BLACK RELATIONSHIP 1924

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Drawings (341.1949)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Drawings (341.1949)

Watercolour and Ink on Paper

Dimensions: 36.9 x 36.2 xm / 14 1/2 x 14 1/4"

© The Museum of Modern Art, New York; VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn 2015

WASSILY KANDINSKY, GESPANNT IM WINKEL 1930

Kunstmuseum Bern, Othmar Huber Foundation

Kunstmuseum Bern, Othmar Huber Foundation

Oil on Cardboard

Dimensions: 48,5 x 53,5 cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2015

KURT KRANZ, GROUP OF FOUR, BLACK & WHITE 1968

Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

Photo: Uwe Jacobshagen

© Ingrid Kranz

© Ingrid Kranz

KURT KRANZ - UNTITLED PICTURE SERIES

( PROJECT FOR AN ABSTRACT COLOR FILM ) 1930

32 Drawings in Watercolor, Gouache, and Ink on Paper,

Mounted on Canvas

Credits: Kunsthalle Bielefeld

KURT KRANZ, OSTINATO OR RHYTHMIC ORDER, 1957

Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

Photo: Uwe Jacobshagen

© Ingrid Kranz

© Ingrid Kranz

OSCAR SCHLEMMER – BAUHAUS STAIRWAY, 1932

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 162.3 x 114.3 cm

Credit: Gift of Philip Johnson

©The Museum of Modern Art, New York

ALFREDO BORTOLUZZI – LA PALUCCA 1935

BAUHAUS – ARCHIV BERLIN

LASZLO MOHOLY NAGY – UNTITLED

( FROM THE PORTFOLIO FOR WALTER GROPIUS ) 1924

KATJA ROSE – COLOUR WHEEL WITH GRADATIONS OF BLACK AND

WHITE

( Colour Exercises From the Bauhaus Dessau ),

1932

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin,

Photo: Markus Hawlik © Hannes Rose, Munich

FRANZ SCALA – THE DREAM 1919

Oil on Burlap

Dimensions: 100 x 190 cm

© Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

PAUL KLEE, DIE HEILIGE VOM INNERN LICHT, 1921

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design, Berlin

© Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

PAUL KLEE –

SCHERZO WITH THIRTEEN, 1922

Oil Transfer

Drawing, Watercolor, Ink, and Pencil on Paper on Board

Dimensions:

27.9 x 35.9 cm

© 2016 Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

During his tenure at the Bauhaus,

Klee explored distinctive ways of image–making, including transfer drawings.

This work was executed by tracing the lines of a pencil drawing through a

black-inked surface onto another clean sheet of paper. The clean sheet received

the outline of the drawing in black as well as additional smudges of excess

pigment, to which Klee then directly added motifs in watercolor and ink. The

arching and angled arrows, before which whimsical figures appear to dance,

indicate motion and spatial depth. The reference to music, a mainstay in Klee's

life and in his Bauhaus activities, is underscored by the word

"scherzo," referring to a vigorous and playful composition, in the

work's title.

http://www.moma.org/collection/works/34652?locale=en

LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE

“Architecture epitomises the human being’s spatial

confrontation with his environment; it expresses how he asserts himself in it

and how he manages to master it.”

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

The leading German avant-garde architect Ludwig Mies

van der Rohe was the third and last Bauhaus director. Appointed by the founding

director of the school, Walter Gropius, he replaced the previous

director Hannes Meyer, who was dismissed for

political reasons in1930. Both the school and the city of

Dessau had hoped that Mies van der Rohe’s authority would have a calming

influence on the school’s radicalised student body. However, because of the

balance of power in Dessau, which was dominated by the National Socialists,

even Mies van der Rohe was unable to maintain the school’s location. He

attempted to continue the school’s teaching activities in Berlin until its enforced

closure in 1932.

Like Walter Gropius before him, who was the dominant

German avant-garde architect when appointed as the founding director of the

Bauhaus in 1919, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was the leading architect in Germany

when he became the third director of the Bauhaus in 1930. A year earlier, his

architectural designs for the spectacular Barcelona Pavilion successfully

represented the achievements of the Weimar Republic at the World Exhibition in

the Spanish metropolis. He did not need the school in order to make a name for

himself or to win commissions. Instead, Mies van der Rohe took on his first

academic teaching post at the Bauhaus. He had been recommended, just like his

predecessor Hannes Meyer, by Walter Gropius, who had retired from his directorial

post in 1928. After Meyer’s dismissal by the city of Dessau, which Gropius had

backed to prevent further Communist radicalisation among the Bauhaus’s

students, the members of the Bauhaus masters’ council and Dessau’s municipal council

believed that a person of Mies van der Rohe’s authority would have a

stabilising effect on the school.

Mies was born in Aachen to a Catholic family of

stonemasons. After completing an apprenticeship as a bricklayer, he was quickly

recommended to various architecture offices due to his extraordinary drawing

talent. He worked for the prestigious architects John Martens and Bruno Paul in

Berlin before starting work with the architect and AEG designer Peter Behrens

in 1908. Here, he met Walter Gropius, likewise an employee, for the first time.

Mies had already built his first house, the art nouveau-influenced Riehl House

in Potsdam-Babelsberg, one year before. In 1911, he built the Perls’ House in

Berlin-Zehlendorf. The Villa Urbig, which he constructed in 1917 in the

neoclassic Schinkel style, is now known as the Churchill Villa. These first

buildings tended to follow more conventional role models.

In autumn of 1915, Mies was conscripted into the army

and commanded to serve in various construction units in Frankfurt am Main,

Berlin and Eastern Europe. In early 1919, he returned to Berlin. With the

revolution of November 1918, some artists had come together in Berlin to

discuss their concepts of modern art and wanted to stimulate the public’s

interest with exhibitions. They founded the so-called November Group and

organised meetings on a regular basis where they discussed and played music.

These evenings were known as the November Group Evenings. Mies van der Rohe

joined the group in 1921, and until 1925, he organised the group’s

architectural entries for the annual Große Berliner Kunstausstellung (great

Berlin art exhibition).

In 1921, Mies van der Rohe also participated in a

competition for a high-rise office building on Friedrichstraße in Berlin. His

unusual – and promptly rejected – design for the block was probably intended as

a programmatic study, which he presented to the public at this opportunity.

From the current perspective, the design is visionary because, for first time,

all of the main floor space was designed for flexible use and the façade was

completely glazed. It is the first example of Mies van der Rohe’s

“skin-and-bones” architecture that was to dominate his later designs.

In 1922, Mies changed his last name with the addition

of “van der” and the maiden name of his mother to “Mies van der Rohe”.

In 1923, Mies van der Rohe constructed his first

building using the modern formal vocabulary: The Ryder House in Wiesbaden is a

cubic residence with light-coloured plaster and a flat roof, which comes close

to the Bauhaus in terms of style. His most extensive project to date followed

in 1927 when Mies realised four multi-family dwellings on the Afrikanische

Straße in Berlin-Wedding. Here, he used prefabricated standard components to

lower construction costs and, with the open grouping of the buildings,

attempted to ensure good illumination and ventilation for the apartments. As a

member of the Association of German Architects (BDA) Mies van der Rohe founded

the progressive and thoroughly controversial collective, Der Ring, in 1924.

That same year, he was invited to join the Deutscher Werkbund (German Work

Federation). Two years later, he was appointed as its vice president. In this

function, he directed the Werkbund’s exhibition Die Wohnung (the flat) held in

Stuttgart in 1927, which resulted, among other projects, in the Weißenhof Estate. At this juncture, Le

Corbusier, who in collaboration with his brother had designed two buildings for

the estate, invited Mies van der Rohe to the founding congress of CIAM (Congrès

Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne). A separate part of the exhibition was

displayed in Stuttgart’s city centre and dealt with modern furnishings. This

was curated by the interior designer Lilly Reich.

In mid-1928, Mies van der Rohe and Reich were

commissioned as artistic directors of the German section of the World

Exhibition in Barcelona. This was probably mainly due to the great success of

the Werkbund exhibition in Stuttgart. Here too, they jointly designed a number

of exhibition areas. Mies van der Rohe also designed an official reception building

for the exhibition – the Barcelona Pavilion. The Barcelona Pavilion, which was demolished

after the 1929 World Exhibition, was not reconstructed until 1986.

In late 1928, Mies van der Rohe began to work on the

design for theTugendhat House in the Czech city of Brno, which was

completed in 1930. In 2001, it became a designated UNESCO World Cultural

Heritage site as an outstanding major work of modern architecture in the

International Style. Although Mies van der Rohe had realised his ideal of “less

is more” here, this “less” was in fact a luxury. Alongside the exorbitant

original construction costs of 1930, just as the impact of the world economic

crisis was starting to be felt, the most recent restoration of this “little”

world heritage site consumed more than 3.5 million euros. In the same year,

Mies van der Rohe also built the Lange

House in Krefeld and

the neighbouring Esters House.

In 1930,

Mies van der Rohe became the director of the Bauhaus Dessau and began his academic teaching

activities. In his brief period at the Bauhaus, Mies van der Rohe was compelled

to make more and more concessions to the political circumstances: Pressured by

the risk of closure, the curriculum became more conventional, the experimental

work was reduced, the workshops were combined and the preliminary course was

eliminated. The duration of the studies was shortened and the tuition fees

increased. The students’ studios remained closed and the Bauhaus GmbH was

dissolved.

The Bauhaus Dessau was closed in 1932 by a newly elected city council with a

National Socialist majority. After complex negotiations in relation to the

dissolution of the city of Dessau’s financial obligations towards the Bauhaus

and its personnel – including the accrued revenues for licensing contracts such