HENRY MOORE: MAGNIFICENT IMPACT IN CONTEMPORARY ART

HENRY

MOORE’S LEGACY

A giant of twentieth century art, today Henry Moore is

considered as the catalyst of the British sculptural renaissance that followed

his rise to fame in his own lifetime. Moore came to represent the post-war

optimism that was manifest in the rebuilding of Britain but this came at a

price, as many became disillusioned at the sculptor’s omnipresence.

Contemporary artists that followed were particularly critical of their

sculptural forefather but many have since acknowledged their debt to Moore who

brought British sculpture into the international spotlight.

MOORE’S SERVICE TO

THE ARTS

At the time of his death Moore had created just over 1,000

sculptures, over 700 graphics and almost 5,500 drawings leaving an incredible

wealth of material to remember him by. To a certain extent Moore secured his

own legacy with great acts of generosity, particularly through gifts to public

collections. In the UK alone these included 36 sculptures and a complete set of

graphics to Tate; a wide array of prints and drawings to the British Museum and

further works to the Victoria & Albert Museum and the British Council.

Moore was also generous with his time and resources to support the arts. He

served as a Trustee of the Tate from 1941 until 1956 and of the National

Gallery from 1955 until 1974. He championed free entry and early Sunday opening

hours at the National Gallery and encouraged the controversial purchases of

works of art accused of being expensive; paintings by Renoir and Cézanne are

today considered to be crucial parts of the gallery’s collection. The impact of

Moore’s patronage and work as a Trustee ensures that his legacy quietly reaches

far beyond the works which bear his name. By establishing the Henry Moore

Foundation before his death, Moore secured the protection of his own works

which would continue to be exhibited internationally. Our grants scheme allows

his legacy to be truly wide-reaching through the funding of sculpture research

and exhibitions.

MOORE & PUBLIC SCULPTURE

After the Second World War,

Britain was rebuilt with a utopic modernist vision. In 1946 the Labour

government passed the New Towns Act prompting the creation of 11 new towns. As

the most prominent sculptor of the day, the work of Moore was called upon to

enhance these towns and other modernist sites. Stevenage was the first new town

to be built, where Family Group, 1948-49 was placed at the entrance of the

Barclay Secondary School, setting a precedent for art in educational

institutions. The second town was Harlow where its master planner Sir Frederick

Gibberd pioneered the commissioning of sculptures for its public spaces. Moore

was the first chosen artist, carving a family group in Hadene stone in response

to the young families who had moved there. A proliferation of international

acquisitions and commissions and his humanist language of family groups and

reclining figures confirmed Moore’s status as a symbol of post-war optimism.

R

‘’ Sculpture is an art of the open air. Daylight,

sunlight is necessary to it, and for me its best setting and complement is

nature. I would rather have a piece of my sculpture put in a landscape, almost

any landscape, than in, or on, the most beautiful building I know. ‘’

Henry Moore in Sylvester 1951: Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore

Tate

1951

Despite architects choosing the work of Moore again and again,

the artist preferred his sculptures to be seen in natural landscapes. Whether

natural scenery or the built environment, Moore’s works have peppered

landscapes around the world since the 1950s. He was the first to publicly

declare that sculpture was best viewed in the outdoors. He sat on the committee

of the first ‘ Open Air Exhibition of Sculpture ' at Battersea Park in 1948

where he showed two sculptures; then a new model, the display proved to be a

catalyst for the emergence of many other open air exhibitions. Moore’s impact

therefore resonates beyond his own work to the way that sculpture continues to

be presented and considered as part of the landscape.

CONTEMPORARY

ARTISTS

‘’ The landscape as subject in sculpture almost enjoyed a

renaissance due to the work of Moore. The work has at times an almost

geological quality. Having been hewn out and eroded, the work often emerges out

of the ground or from a plinth-like device that holds different elements

together, giving the appearance of rock formations. This reference gives the

work an almost geological time-scale, usually unobtainable by human beings.

Moore placed his work outdoors, often directly in the landscape, more than any

other sculptor previously had done. As a result, the landscape, which had been

neglected for many years, became the focus of attention for artists. ‘’

Tony

Cragg, Body and Void: Echoes of Moore in Contemporary Art

Henry Moore

Foundation 2014

A

teaching career spanning 1925 to the early 1950s produced a generation of

artists who were directly touched by Moore’s example. Many of his assistants

such as Anthony Caro and Bernard Meadows became established artists in their

own right. Caro wrote “for me, working as his assistant opened up a whole new

visual world. He loved to talk about art, and despite the age difference we had

a good dialogue. Sculpture was his life. He was in touch with his feelings,

very direct.

Despite Moore’s direct contact with, and support of, many

contemporary artists his reputation amongst the younger generation suffered.

Moore was widely considered an establishment artist, probably due to the

prominence of his works in institutions and public spaces over the world.

However, this opinion doesn’t acknowledge the fact that Moore had refused to

become a member of the Royal Academy and turned down a knighthood in 1950. Many

artists preceding Moore sought to escape his shadow by taking a completely

different aesthetic and even publicly deriding the artist

When Moore first announced a gift of works to the

Tate, 41 contemporary artists signed a letter in the Times arguing that this

would leave no room for the display of other contemporary artists. To the

dismay of Moore, signatories included his prior assistants Caro and Phillip King.

Moore was hurt by public criticism, but he had similarly condemned his own

sculptural forefather, Auguste Rodin, early in his career. Like many of the

artists who followed Moore, later in his career Moore admitted his debt to

Rodin.

‘’ But you know, if you like something tremendously you may react and

think you’re against it, but inside you can’t get away from it. This is what

happened to me over Rodin. Gradually, I began to realise that a lot of things

one might be using and being influenced by – Negro sculpture for example, which

gives you a simplified programme to work on – are, compared with Rodin, too

easy, so as time has gone on, my admiration for Rodin has grown and grown.'

Henry Moore, Rodin: Sculpture and Drawings, the Hayward Gallery

London, 1970

If many artists remain hesitant to acknowledge a stylistic debt to Moore, most

do admit that he gave them the ambition to strive for similar heights.

‘’ If it

hadn’t been for him I don’t believe English sculptors would have had half the

confidence which is apparent today, half a century after Henry. Henry gave

English sculptors who followed him the confidence to feel they could be as good

as the best, could take themselves seriously and be taken seriously. ‘’

Anthony

Caro, Celebrating Moore

The Henry Moore Foundation 2006

‘’ Moore was a

bit the elephant in the room for my generation, something so big you couldn’t

see him. Or didn’t want to. However, I do think that when, in the mid-1960s,

the Observer could run a cover article titled The Greatest Living Englishman

about Henry Moore, then it did both licence a degree of ambition and signified

a level of aspiration for young men and young women that would be hard to

overstate. ‘’

Richard Deacon, Body and Void: Echoes of Moore in Contemporary

Art

The Henry Moore Foundation 2014

In 2014 the Henry Moore Foundation staged ‘ Body and

Void: Echoes of Moore in Contemporary Art ‘, an exhibition which celebrated the

debt of contemporary artists to Moore’s aesthetic. The exhibition included

works by Joseph Beuys, Tony Cragg, Antony Gormley, Damien Hirst, Anish Kapoor,

Sarah Lucas, Bruce Nauman and Rachel White read amongst others. The influence

of Moore can be discerned in these artists and much further afield.

THE FUTURE

OF MOORE’S LEGACY

The legacy of Moore continues to develop. At the Henry Moore

Foundation, we persist in working towards achieving his goals of promoting his

work and supporting sculpture

through his legacy. Critical theory sheds new light on

Moore and contemporary artists continue to respond to his work in new ways. The

vitality of Moore’s works that he left behind in public and private spaces

encourages belief that they will be enjoyed for generations to come.

https://www.henry-moore.org/about-henry-moore/henry-moores-legacy

You may reach to read Henry Moore's past exhibition news at Rijksmuseum and museum architecture information to click below link.

https://mymagicalattic.blogspot.com.tr/2013/08/henry-moore-exhibition-at-rijksmuseum.html

TWO RECLINING FIGURES WITH RIVER BACKROUND - 1963

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 305 x 629 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Five Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 52

© The Henry Moore Foundation

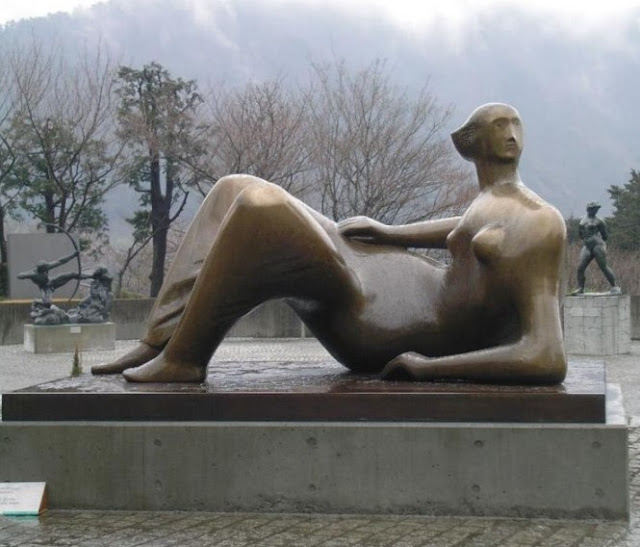

RECLINING FIGURE – 1959/64

Royal Academy

© The Henry Moore Foundation. Gift of

Irina Moore

MULTICOLOURED RECLINING FIGURE - 1967

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 140 x 197 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Four Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 99

© The Henry Moore Foundation

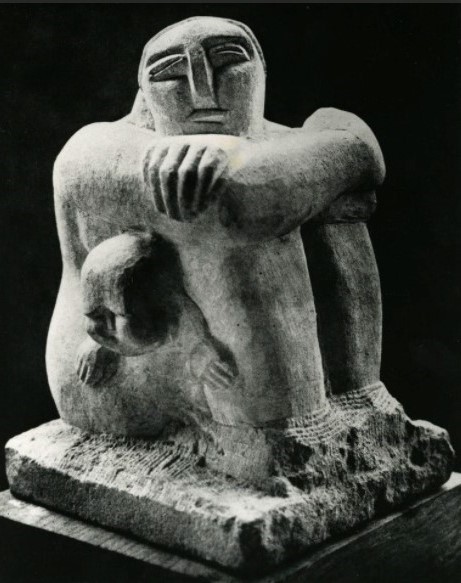

RECLINING FIGURE - 1929

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 54 × 82 × 37 cm

Material: Brown

Hornton Stone

Catalogue Number: LH 59

Credit Line: Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art

Gallery).

Bought With the Aid of a Grant From the Board of

Education and

The Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund,

1941

EIGHT RECLINING FIGURES - 1967

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 260 x 229 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Four Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 97

© The Henry Moore Foundation

EIGHT RECLINING FIGURES WITH ARCHITECTURAL BACKGROUND

- 1963

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 432 x 330 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Five Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 44

© The Henry Moore Foundation

EIGHT RECLINING IN YELLOW, RED & BLUE - 1966

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 317 x 286 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Six Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 58

© The Henry Moore Foundation

TWO STANDING

FIGURES (HENRY MOORE FOUNDATION TEX. 20), 1948

Screenprint

in Colors,

Signed

in Ink, Dated and Numbered 15/30, on Irish Linen

Dimensions: Overall: 2565 by 1781 mm

Dimensions: Overall: 2565 by 1781 mm

© The

Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

WOMAN HOLDING

CAT (CRAMER 10)

Colograph

Printed in Colors, 1949, Signed in Pencil, Dated and Numbered 74/75, on English

Cartridge Paper, Printed and Published by Ganymed Original Editions Ltd.,

London, Framed

Dimensions: Image: 298 by 488 mm

Sheet: 355 by 532 mm

Dimensions: Image: 298 by 488 mm

Sheet: 355 by 532 mm

© The

Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

RECLINING FIGURE - 1975

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 213 x 283 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Six Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 366

© The Henry Moore Foundation

FOUR RECLINING FIGURES - 1973

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 419 x 622 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Four Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 282

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

FIGURES WITH SKY BACKGROUND II - 1981

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 257 x 346 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Eight Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 609

© The Henry Moore Foundation

DRAPED RECLINING FIGURE - 1978

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: Artwork (Published Dimension): 182 cm

Material: Roman

Travertine Marble

Catalogue Number: LH 706

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Acquired 1986

RECLINING FIGURE - 1967

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 114 x 168 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Four Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 100

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING FIGURE – 1959/64

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: Artwork: 114.5 x 261.5 x 91 cm

Material: Elmwood

Catalogue Number: LH 452

SIX RECLINING FIGURES WITH BUFF BACKGROUND - 1963

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 457 x 585 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Two Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 50

© The Henry Moore Foundation

SILHOUTTE FIGURES WITH BORDER DESIGN - 1973

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 482 x 451 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Two Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 297

© The Henry Moore Foundation

SIX RECLINING FIGURES - 1973

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 317 x 381 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Four Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 298

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECUMBENT FIGURE - 1938

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: Artwork: 139.7 cm

Material: Green

Hornton Stone

Catalogue Number: LH 191

Credit Line: The Trustees of the Tate Gallery, London:

Presented by

the Contemporary Arts Society, 1939

RECUMBENT FIGURE - 1938

STONE RECLINING FIGURE - 1979/80

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 985 x 1835 mm

Material: Etching,

Aquatint & Drypoint in Black

Catalogue Number: CGM 568

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING FIGURE – 1945/6

Dartington Hall, Devon

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: The Henry Moore Foundation Archive

EVE - 1980

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 267 x 356 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Eight Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 575

© The Henry Moore Foundation

GROUP OF RECLINING FIGURES - 1973

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 457 x 397 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Eight Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 241

© The Henry Moore Foundation

TWO RECLINING FIGURES - 1976

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 240 x 290 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Four Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 440

© The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation

SEVEN SCULPTURAL IDEAS - 1973

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 336 x 258 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Two Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 296

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING FIGURE - 1974

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 160 x 238 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Five Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 387

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RHINOCEROS - 1981

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 213 x 277 mm

Material: Etching

in Black

Catalogue Number: CGM 634

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING FIGURE: ARCH LEG – 1969/1970

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 260 x 466 cm

Material: Bronze

Catalogue Number: LH 610 cast 0

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Acquired 1987

LIFE

FORMS: HENRY MOORE, MORPHOLOGY & BIOLOGISM IN THE INTERWAR YEARS BY EDWARD

JULER

New images of microscopic life and theories of

biological development impacted profoundly upon Moore’s practice, leading him

to adopt in the 1930s a biomorphic sculptural idiom that echoed the forms of

living nature.

In his polemical introduction to modern painting and sculpture,

Art Now (1933), the British critic Herbert Read identified two ‘methods’, which

he felt best described the approaches to art taken by contemporary artists. The

first of these was an ‘empirical’ approach, which aimed to reproduce appearances.

For Read, such dumb fidelity to surface appearances rendered the artist as

little more than a slave to ‘the physiological mechanism of his sight’, and

represented an aesthetic dead end.1 The second method – and in his opinion, the

most productive – he labelled ‘scientific’. This approach required the artist

to interrogate the structural nature of objects, in effect, playing the role of

a scientist. The artist, Read wrote, ‘realises that the outward appearance of

objects depends on their inner structure: he becomes a geologist, to study the

formation of rocks; a botanist, to study the forms of vegetation; an anatomist,

to study the play of muscles, and the framework of bones’.2

No modern artist

embodied more fully Read’s scientistic ideal than Henry Moore.3 In a monograph

on the artist, published in 1934, Read saw the preponderance of natural forms

in Moore’s work as symptomatic of biologistic sympathies:4

[The] artist makes

himself so familiar with the ways of nature – particularly the ways of growth –

that he can out of the depth and sureness of that knowledge create ideal forms

which have all the vital rhythm and structure of natural forms ... Henry Moore

has ... sought among the forms of nature for harder and slower types of growth,

realizing that in these he would find the forms natural to his carving

materials. He has gone beneath the flesh to the hard structure of bone.5

Indeed,

Moore, made no secret of his interest in natural history, peppering his

statements with allusions to biological principles and organic form in the

1930s and later.6 Interviewed by Arnold Haskell in 1932, he spoke of the

importance of morphology to his practice, explaining, in particular, his joy at

discovering new biological precepts to apply to his art: ‘I have studied the

principles of organic growth in the bones and shells at the Natural History

Museum and have found new form and rhythm to apply to sculpture’.7 This essay

will thus explore Moore’s biologistic leanings in relation to contemporary

theories of morphology, biomorphism, neo-vitalism and organicism.

SHAPES IN

TRANSITION: MOORE, MORPHOLOGY & D’ARCY WENTWORTH THOMPSON

No project more

eloquently conveyed Moore’s biological interests than a series of experimental

drawings he produced in the early 1930s, which would come to be known as his ‘

Transformation Drawings ‘. Seeking to disclose the ‘principles of form and

rhythm from the study of natural objects’, Moore suggested that these sketches

of bones, tree-roots and lobster claws – pictured in various stages of rotation

– were graphic studies of the morphological laws that

underpinned the construction of form in nature.8 The most conspicuous aspect of

his ‘ Transformation Drawings’ is the way in which the angle of vision

drastically changes the form of the object represented. One study of a pelvic

bone, for instance, dynamically illustrates a section of a pelvic girdle

variously viewed head-on, sideways, from the bottom and from a bird’s eye view

(fig.1).

Here Moore’s familiarity with biology is evinced by the way in which

the Transformation Drawings subtly echo the principles of organic form laid out

in D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s morphological masterpiece, ‘ On Growth and Form

‘ (1917).9A scholar of natural history, Thompson steadfastly believed that the

laws of mathematics could be used to explain the principles of growth and form

in living matter and spent many years developing a theory to elucidate how

every biological object was effectively a ‘diagram of forces’, shaped in time

and space by quantifiable physical energies.10 Thompson’s book was heralded by

scientists as making a substantial contribution to the field of experimental

morphology. On the one hand, his thesis presented evolution in novel terms, as

a sudden and mercurial force, rather than (as was traditionally contended by

Charles Darwin and his nineteenth-century disciples) something slow and steady.

On the other, Thompson’s rigorous adherence to mathematical law proffered a

timely riposte to the mysticism that had begun creeping into early twentieth-century

biology.11 In the long run, Thompson’s work helped birth the science of

biomathematics and, to this day, has influenced a wide array of disciplinary

fields, including art, architecture, anthropology (his morphology possessed

great resonance for the nascent structuralism of Claude Lévi-Strauss),

geography and cybernetics, to name but a few.12

Thompson’s eloquent

descriptions of living form sprouting, ballooning and metamorphosing into

mathematically harmonious shapes particularly appealed to those artists who

looked to nature for evidence of universal form values and for a re-vivifying

alternative to contemporary abstraction’s mechanistic bias.13 For his part,

Moore claimed to have first encountered ‘ On Growth and Form ‘ while a student

at Leeds College of Art in the early 1920s,14 but, in truth, his interest

formed part of a larger wave of modernist enthusiasm for the book which began

during the 1930s and saw figures such as Read and the constructivist artist,

Naum Gabo, introducing Thompson’s ideas to their close-knit circle of artistic

and intellectual friends in London.15

Over and above its importance as a

canonical work of morphology, ‘ On Growth and Form ‘ attracted non-specialists

because of its apparent accessibility and Thompson’s tendency to launch into

contemplative, lyrical discussions of the aesthetic and philosophical

implications of ‘form’. Indeed, Thompson’s poetic style of exposition and

fondness for literary and philosophical references encouraged non-specialist

reviewers to applaud ‘ On Growth and Form’s ‘ artistic flair, proclaiming it to

be as much a great work of literature as it was of science.16 In a review of

the 1942 edition of On Growth and Form, Read enthused that Thompson was ‘of the

same ‘blood and marrow’ as Plato and Pythagoras, and [had] something of the

geniality of a Goethe or a Henri Fabre’ and, as such, his book should

become ‘layman’s property and be given general currency’. Indeed, Read was in no doubt as to the volume’s importance to artistic practice, claiming that he felt ‘confidence in pointing out the significance which this science of form has for the theory of art’. ‘Never before has such a range of specific natural forms been shown to possess the harmony and proportion we usually ascribe only to works of art.’17

Fascinated by the psychology of

beauty, Read’s interest in morphology had been piqued during the early 1930s

when he first began researching ‘the motives that lead man to prefer one shape

to another’.18 Describing the course of this research in his semiautobiographical

text, ‘ Annals of Innocence and Experience ‘ (1940), he explained that: ‘It was

a short and obvious step to recognise at least an analogy and possibly some

more direct relation, between [the] morphology of art and the morphology of

nature. I began to seek for more exact correspondences, first by making myself

familiar with the conclusions reached by modern physicists about the structure

of matter, and then by exploring the quite extensive literature on the

morphology of art’.19 These studies (which began as analyses of proportion in

the BBC weekly, the Listener, in 1931) soon developed into a much bigger

project in which Read sought to clarify how the Golden Section had played so

‘preponderant [a] part in the morphology of the natural world’ as well as

art.20 Thus, ‘ On Growth and Form ‘ resonated particularly loudly for Read as

Thompson, more than any other science writer, seemed to demonstrate ‘that

certain fundamental physical laws determine even the apparently irregular forms

assumed by organic growth’ and, in so doing, provided the grounds for

analogizing between the morphologies of art and nature.21 Even though it is

imaginable that his relationship with artists such as Moore and Gabo

highlighted Thompson’s artistic significance for Read,22 his wider

preoccupation with creating an ‘empirical’ theory of aesthetics stretched back

a good deal further – to his previous incarnation as a literary critic and

curator in the mid-1920s, when he acknowledged the role that physics and

psychology had jointly performed in discrediting ‘transcendental reasoning’

while simultaneously shedding light on the ‘material origins of art’.23

Read’s

engagement with morphology formed part of a wider current of enthusiasm for

morphology which had begun, in 1914, with the publication of the British art

critic, Theodore Cook’s ‘ The Curves of Life ‘ and which, arguably, reached its

apogee with the publication of the Romanian mathematician and writer, Matila

Ghyka’s 1931 aesthetic thesis, ‘ The Golden Number ‘. Both of these

publications were hugely important to Read’s developing morphological

aesthetic; yet whereas Ghyka was cited as providing the ‘best up-to-date

summary’ of the morphology of art it was ‘ On Growth and Form ‘ that Read

recommended the reader consult to obtain ‘a more fundamental work,

investigating the laws under which organic life evolves’.24

Within ‘ On Growth and Form ‘, it was arguably

Thompson’s chapter on ‘The Theory of Transformations’ that had the greatest

impact upon Moore’s artistic practice.25 Utilising a grid-like system of

mathematical co-ordinates to plot the shape of an organism, Thompson contended

that any bodily deformation could ultimately be used to demonstrate a

morphological kinship between species (fig.2). In addition, Thompson’s method

of ‘transformation’ made it possible to hypothesise the intermediary but as yet

undiscovered forms through which an organism had to pass before it evolved into

another species:

'' [It] is obvious ... that this [method] may also be employed

for drawing hypothetical structures, on the assumption that they have varied

from a known form in some definite way. And this process may be especially

useful, and will be most obviously legitimate, when we apply it to the

particular case of representing intermediate stages between two forms which are

actually known to exist, in other words, of reconstructing the transitional

stages through which the course of evolution must have successively travelled

if it has brought about the change from some ancestral type to its presumed

descendant.26 ''

The relevance of Thompson’s hypothesis to Moore’s

practice can be judged by the simple fact that his ‘ Transformation Drawings ‘

formed the basis for many of his largescale sculptures in wood and stone. One

sketch, for example, shows a jawbone imaged from a bewildering array of

viewpoints (fig.3). Resting on its bottom edge in the central image, the

mandible is at its most recognisable; the deep hollow on the upper left-hand

side of the jaw and the jutting row of teeth signalling its corporeal origins.

Moore, however – in a ‘ tour de force ‘ of artistic extemporisation – inverts

the object, turns it upside down, rotates it and subtly alters its profile. In

one image he adds the slightest hint of a face (three mere pinpricks for the eyes

and mouth) while, in another, he exaggerates the contours of the jawbone to

suggest the bulging forms of arms, legs and head. Thus transmogrified, the

resulting images powerfully recall the turgescent, reclining forms that typify

Moore’s sculpture of the period.

Many of Moore’s morphological drawings include

pencilled annotations scribbled across the page. These notes were used as a

sort of creative shorthand for the sculptural process, enabling Moore to

visually ad-lib upon the morphology of natural objects and imagine hypothetical

forms, connected to the form depicted and yet part of a new and unique artistic

configuration. Scrawled across the jawbone sketch, for example, is the legend:

‘In transferring studies into stone – harden & tighten, stiffen, taughten

[sic] them up’.27 In a statement published in 1934 Moore summed-up the

morphological properties of various natural objects in terms strikingly

redolent of Thompson’s opus:28 ‘Bones’, he wrote, for example, ‘have marvellous

structural strength and hard tenseness of form, subtle transition of one shape

into the next and great variety in section. Trees (tree trunks) show principles

of growth and strength of joints, with easy passing of one section into

the next.

They

give the ideal for wood sculpture, upward twisting movement. Shells show

Nature’s hard but hollow form and have a wonderful completeness of a single

shape.’29 Here Moore’s comment on the formation of bones closely echoes

Thompson’s elegant account of the morphological forces to which bones are

subject during their growth cycles:

'' [We] have no difficulty in seeing that the

anatomical arrangement of the trabeculae follows precisely the mechanical

distribution of compressive and tensile stress ... The lines of stress are

bundled close together along the sides of the shaft, and lost or concealed

there in the substance of the solid wall of bones; but in and near the head of

the bone, a peripheral shell of bone does not suffice to contain them, and they

spread out and through the central mass in the actual concrete form of bony

trabeculae.30 ''

Given Read’s own deep knowledge of Thompson’s morphology, it is

possible that this passage inspired his extraordinarily Thompsonian reading of

Moore’s nature-centric practice. In his 1934 monograph on the artist he spoke

of the natural forms that served as models for Moore’s work using Thompson’s

language of tensile stress and strain: ‘Bones combine great structural strength

with extreme lightness; the result is a natural tenseness of form. In their

joints they exhibit the perfect transition of rigid structures from one variety

of direction to another. They show the ideal torsions which a rigid structure

undergoes in such transitional movements’.31 Conceptualised within a

morphological framework, Moore’s practice thus symbolised the quintessence of

Read’s ‘scientific’ method, in which the artist realised ‘that the outward

appearance of objects depend[ed] on their inner structure: [becoming] an

anatomist, to study the play of muscles, and the framework of bones’.32 ‘

THE BIOMORPHIST PRODUCING VIABLE WORK ’: MOORE

& BIOMORPHISM

Biology’s centrality to Moore’s practice was discussed

most fully by the English critic Geoffrey Grigson in his 1943 monograph titled

simply Henry Moore. ‘Biology must be acknowledged’, he pleaded, as a wellspring

of inspiration for the contemporary artist and nowhere was this more evident

than in Moore’s turgescent, fluid shapes. These ‘may be related to a breast, or

a pear, or a bone, or a hill ... But they might also relate to the curves of a

human embryo, to an ovary, a sac, or to a single-celled primitive organism.

Revealed by anatomy or seen with a microscope, such things are included now in

our visual knowledge’.33

A poet by profession, Grigson founded the literary

review New Verse in 1933 and, in the pages of the modernist art magazine ‘ Axis

‘, formulated the term ‘biomorphism’ to describe the sort of organic,

semi-abstracted forms favoured by Moore and some other contemporary artists.34

Drawing upon the nineteenth-century anthropology of Alfred Court Haddon and the

biologistic criticism of the German art historian, Wilhelm Worringer, he coined

the term to describe artworks that were neither representational nor wholly

abstract but rather appeared to owe their origins, symbolically as much as,

or

more than, visually, to living things.35 In a couple

of essays published in 1935, Grigson spelt out the aesthetic implications of

the biomorphic idiom:

'' They are [artworks] in which an organic-geometric tension

is very well obtained. Many of their forms are almost certainly ‘degraded’, as

orthodox anthropologists would say, from organic forms which came nearer to

nature. Some forms are further from any originals, and those have been

described as ‘biomorphic’, which is no bad term for the paintings of Miro,

Hélion, Erni and others, to distinguish them from the modern geometric

abstractions and from rigid Surrealism.36 ''

Within this critical framework

Grigson left no doubt that it was Moore who most closely met his biomorphic

ideals:

'' Product of the multiform inventive artist, abstraction-surrealism

nearly in control; of a constructor of images between the conscious and the

unconscious and between what we perceive and what we project emotionally into

the objects of our world; of the one English sculptor of large, imaginative

power, of which he is almost master; the biomorphist producing viable work,

with all the technique he requires.37 ''

While the appellation ‘biomorphic’ could

refer to natural form in the widest possible sense – encompassing objects as

diverse as, nuggets of bone and the shapes of animals – it nevertheless relied

upon the findings of biology to articulate fully the range of meanings to which

it was subject.38. Artworks that conveyed a sense of vitality – such as

sculptures by Constantin Brancusi, Hans Arp and Moore – were discussed by

Grigson in biological terms, as abstract ciphers of vital energies or

microscopical forms: ‘It is Brancusi whose polished unicellular forms have been

the basis for such different figures, more complex, more ‘impure’, as those of

Mr Henry Moore’, he wrote in 1935.39 Yet while the fluid, protoplasmic forms of

Arp and other biomorphic modernists evoked what Alfred Barr, director of the

Museum of Modern Art in New York, would characterise as ‘the silhouette of an

amoeba’,40 it was Moore’s swollen, pullulating shapes in wood and stone that –

in Grigson’s eyes at least – most fully testified to biology’s influence on

modernist art.41 ‘When I look at [Moore’s] carvings’, he wrote in 1943, ‘I

sometimes have to reflect that so much of our visual experience of the

anatomical details and microscopical forms of life comes to us, not direct, but

through the biologist’.42

THE SMALLEST UNITS OF CREATION: PHOTOMICROGRAPHY,

BIOROMANTICISM & MOORE Photographic technology advanced enormously in the

1920s and 1930s.43 New methods of lens manufacturing better enabled the

scientific visualisation of microscopic forms and tissue samples, while better

lighting and staining techniques helped enhance the quality of the increasing

number of micrographic images that found their way into the pages of the

popular press.44The photography critic G.H. Saxon Mills, writing in 1931,

hinted at the artistic importance of these technological innovations by

speaking of

In tandem with photomicrography, microcinematography also

developed rapidly as a field as early film pioneers such as Jean Painlevé and

Jean Comandon thrilled European cinema audiences with speeded-up and slow

motion films of aquatic life, single-celled organisms and sprouting

plant-life.48 Despite the scientific community’s dismissive attitude towards

the use of such films as 'entertainment', the new genre boomed in popularity,

particularly delighting avant-garde viewers who saw, especially in Painlevé’s

films, evidence of an aesthetic sensibility skilfully choreographing the

wonders of nature.49 ‘The science films of Jean Painlevé’, wrote the French

critic Elie Faure, ‘in showing the dancing and glittering life of a mosquito,

bring to mind the enchantment of Shakespeare and allow one to glimpse the

exhilaration of the mathematician lost in the silent music of infinitesimal

calculations’.50 Nature-centric modernist artists – such as László Moholy-Nagy

– championed the birth of these photographic technologies, claiming that a new

age of mechanical objectivity would purify the aesthetic sensibility and

destroy pictorialism’s bankrupt artistic pretensions. Indeed, for Moholy-Nagy,

photography had dramatically revolutionised vision by optically re-framing

humanity’s understanding of the visible world and allowing modern artists to

engage anew with visual reality. His highly influential book of 1925, Painting

Photography Film, gave visual form to the objective bent of the new

photography. Using examples drawn from a wide range of photographic

technologies (including illustrations of scientific photography, such as

photomicrography and X-rays), Moholy-Nagy urgently demonstrated the new

photography’s decisive break with pictoralist art and the dazzling range of

vision that modern lens technology offered the artist. 51

In Britain the

emergence of the documentary cinema movement significantly enhanced

microcinematography’s presence in the public eye. By the end of 1929 almost a

hundred natural history films had been produced by the company British

Instructional under the series title of ‘ Secrets of Nature ‘ and shown to

popular acclaim. An influential contributor to this series was Percy Smith, who

had experimented successfully with making time-lapse films of plant life, which

sped-up the process of growth by up to 96,000 times.52 While ‘ Secrets of

Nature ‘ represented a diverse cinematic portfolio, ranging from feeding time

at the zoo to meteorological documentaries, a significant number of its

‘shorts’ were microcinematographic films tackling topics like pond life,

germination and insect life. ‘ Magic Myxies ‘ (1931),

for example, revealed the magnified life cycle of a slime fungus, sped-up to

take place within a ten minute time-span.

The proliferation of

photomicrographic imagery led to frequent comparisons between modernist

sculpture and microscopical form. In his photo-album of magnified natural

structures, ‘ World beneath the Microscope ‘ (1935), W. Watson Baker

accompanied the photograph of a sea-urchin shell, shot in extreme close-up,

with the caption: ‘The modern sculptor must envy the massiveness of form, the

grandeur of contour, of this small shell, whose dovetailing makes a strange and

interesting pattern’.53In turn, the modernist painter and critic John Piper

felt that such photomicrographic enlargements revealed an underlying affinity

between scientific photography and modern art: ‘It is amusing in fact to turn

the pages and notice the artists suggested by the photographs: Klee (anchors

and plates of Synapta), Ernst (a great many times), Miró (sponge spicules),

Giacometti (chemical crystals), and so on’.54 Similarly, in an essay –

published in Apollo in 1930 – the Scottish documentary film-maker, John

Grierson, provocatively suggested that the ‘organic’ qualities of modernist

sculpture stemmed from the influence of microcinematography on the optical

unconscious: '' It comes from a quickened consciousness of organic life which I am

apt to think is the special stock-in-trade of a new generation. It may be that

cinema has done something to open our eyes in this respect, with its power of

revealing the constructions of plant life, animal life, and all life together

in motion. It would still be more accurate to say that biology is getting into

our blood. Certainly we become more conscious of the sculptural relations

between these different worlds.55 ''

On the question of artistic modernism’s

relationship to scientific imaging technology Moore was just as forthright. In

a text published in ‘ Unit One ‘ (1934), a book of artist statements edited by

Herbert Read, he recognised that the evolution of scientific technologies had

impacted upon his practice: ‘There is in Nature a limitless variety of shapes

and rhythms (and the telescope and microscope have enlarged the field) from

which the sculptor can enlarge his form-knowledge experience’.56

Visually,

Moore’s sculpture bore all the hallmarks of a biologist’s awareness of nature’s

microscopical structures. Artworks such as the amoebic ‘ Two Forms ‘ of 1934

(fig.4) powerfully convey the impression of swollen, cellular forms, gently

distended by the dynamic flux and flow of internal fluids. The protuberant ‘

Composition ‘ 1932 (fig.5) correspondingly recalls the bulging asymmetry of

microorganisms – as revealed in Watson Baker’s photomicrograph of Vorticella

(fig.6) – and gives iconographic credence to Grigson’s claim that ‘[Moore] is

interested in the round, solid shapes into which life builds itself’.57 That

photomicrography offered artistic modernists, like Moore, a form vocabulary

that artfully blurred the boundaries between representation and abstraction was

a refrain that echoed loudly within the pages of modernist magazines and

reviews.58

'' Even the most

impassive observer would be thrilled to see that the enlargement of parts of

plants visible to the eye could be as extraordinary as plant cells glimpsed

through a microscope. When we remember that Klee and, even more, Kandinsky

worked for so long on the elaboration of forms which only the intervention of

the microscope could – brusquely and violently reveal to us, we notice that

these enlargements of plants also contain original stylistic forms.60 ''

In

Britain the publication of Blossfeldt’s macrophotographs caused something of a

media sensation, leading to an editorial in the Times, three pages of coverage

in the Illustrated London News and a flurry of reviews in the arts pages of newspapers

and journals such as the Listener, the Architectural Review and the Times

Literary Supplement.61 This was accompanied by an exhibition, curated by Robert

Wellington, at the Zwemmer Gallery (the exhibition space of Blossfeldt’s

English publisher, Zwemmer), which daringly juxtaposed Blossfeldt’s close-up

photographs of seed-heads, burs and blossom with examples drawn from industrial

design and the applied arts.62 For those of a neo-romantic

disposition,63Blossfeldt’s close-ups provided evidence of photography’s ability

to furnish artists with motifs drawn from the organic world (fig.7).64 Thus,

the painter, photographer and critic, Paul Nash, commented in a review of

Blossfeldt’s book in 1932 on the camera’s prodigious capacity for transforming

the artist’s world view:

'' Obviously, in certain cases, natural forms have

supplied a motif, but in many it would have been impossible to detect the

significance of natural design without the aid of a mechanical process. This is

where the camera’s ‘eye’ proves its incalculable power, but not as an

archaeological, botanical or merely curious discoverer of ‘interesting’

comparisons between art and nature; its importance lies, surely, in the wealth

of matter it places at the disposal of the modern sculptor or painter.65 ''

Blossfeldt’s photographs also provided the basis for the critic Reginald

Wilenski’s critique of modernist sculpture, ‘ The Meaning of Modern Sculpture ‘

(1932). The apparent orderliness and symmetry of Blossfeldt’s close-ups gave

the lie to claims that the abstract prejudices of modernist sculpture were a

rejection of ‘life’ and ‘nature’. On the contrary, noted Wilenski:

'' It is

impossible to sustain the Romantic notion of a wild, free, ragged, ‘nature’

when we examine the enlarged photographs of plant forms in Professor

Blossfeldt’s [books]. These photographs transform the apparently ragged

constituents of a tangled hedgerow into a series of structures informed with a

most definite shape, with most evident order and most evident logic. The study

of these photographs makes it quite clear that ... the artist who gives us

truth to form is the artist who symbolises the forms contained

in the hedgerow by geometric forms.66 ''

Although Wilenski, in championing an

ordered and geometric form of artistic modernism, diverged from Grigson’s

biomorphic middle-ground between ‘the new preRaphaelites of ‘ Minotaure ‘ and

the unconscious nihilists of extreme geometric abstraction’, like Grigson, he

was convinced of the contemporary impact of biological form on modernist practice

and singled-out Moore’s abstract semi-figurations as symbolising ‘the formal

principles of life’.67 ‘I have done my work badly’, he claimed, ‘if [the

reader] does not regard ... Moore’s ‘ Composition ‘ ... as an enlargement of

experience by imaginative organisation of form symbolic of

human-animal-vegetable life’ (fig.8).68

The impression that there was a

powerful relationship between photographic technology and modernist art was

hypothesised by the Hungarian art theorist Ernö Kállai during the late 1920s.69

Motivated by Benjamin’s critique of Blossfeldt and Moholy-Nagy’s 1929 ‘ Film

und Foto ‘ exhibition, which aestheticised the new scientific photography,

Kállai theorised that technology, especially microscopy and x-ray photography,

had revealed the ‘deep structure’ of the world in ways that paralleled the

aesthetic intuitions of artistic modernists.70 The type of art which appeared

as a result of this biological insight – what perhaps might be termed

biomorphic modernism – Kállai labelled ‘bioromanticism’ and saw, in

quasi-mystical, neo-romantic terms, as a technological return to nature.71

Kállai’s biologistic speculations formed part of a larger wave of neo-romantic

thought which emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a

philosophical response to the perceived shortcomings of materialism, positivism

and mechanism and which included ‘a belief in the primacy of life and life

processes, of biology as the paradigmatic science of the age, as well as an

anti-anthropomorphic worldview’.72 This biologistic wellspring of neo-romantic

sentiment held common cause against reductionist ideologies, preferring instead

those philosophies – such as vitalism, holism and monism – which championed a

pantheistic, holistic or biophilic attitude towards life.73

In Britain the

impact of biologistic philosophies on thinking about the direction and values

of contemporary art was evident not only in Grigson and Wilenski’s art

criticism but also in the statements of Read and Moore, both of whom regularly

espoused a biologistic viewpoint in their writings on art. Read, in particular,

was inspired by the neovitalist theories of the French philosopher, Henri

Bergson, whose vision of an incorporeal ‘vital’ impulse – the élan vital –

which creatively shaped evolutionary development achieved widespread popular

acclaim upon its publication in 1907.74 As late as 1955, Read maintained that

‘the inspiration I continue to receive from the only metaphysics that is based

on biological science [is] the metaphysics of Henri Bergson’.75

In

essence, neo-vitalism – from which Bergson’s philosophy derived – profoundly

rejected the materialist idea that living organisms were simply complex

machines and that ‘mind’ itself was little more than a by-product of

biochemical processes. Instead, neo-vitalists recognised ‘life’ and ‘mind’ as

dynamic, immaterial forces that actively intervened in the biological

development of organic matter; yet, in so doing, flouted the accepted laws of

chemistry and physics.76 Arguably, the greatest contemporary ally to the cause

of neo-vitalism was the German biologist, Hans Driesch (1867–1941), whose

experiments with sea-urchin embryos led him to think of organisms as dynamic

selfadjusting bio-systems, the development of which was, to some extent, independent

of physico-chemical forces.77 Translated by C.K. Ogden into English in 1914,

Driesch’s work – like Bergson’s – was a catalyst for the emergence of the

neo-vitalist movement in Britain and spurred writers and philosophers as

diverse as D.H. Lawrence, George Bernard Shaw and C.E.M. Joad to introduce a

vitalist, pantheistic viewpoint to their work.78In the case of Read, the effect

of neo-vitalism on his aesthetic is perhaps most evident in an early piece of

writing on Moore – published in The Meaning of Art in 1931 – in which Moore’s

‘greatest success’ was defined as his ability to visualise form within the

unshaped block of stone:

'' We cannot see all round a cubic mass; the sculptor

therefore tends to walk round his mass of stone and endeavour to make it satisfactory

from every point of view. He can thus go a long way towards success, but he

cannot be so successful as the sculptor whose act of creation is, as it were, ‘

a four-dimensional process growing out of a conception which inheres in the

mass itself ‘.79 ''

Here neo-vitalism is incorporated into an aesthetic that

privileges the immaterial, creative agency of the artist. By likening the act

of artistic creation to an élan vital which – like the kernel of a sprouting

seed – implants within the block of stone or wood the germ of aesthetic

vitality, Read equates Moore to a god-like creator ‘who [does] not replicate

given objects, but adds new ones to the repertory of nature’ – an opinion that,

as the art historian Rosalind Krauss has shown, was common within biocentric

modernist circles in the 1930s.80 A neo-vitalist sensibility is similarly

evident in Moore’s artistic philosophy. Just as an incorporeal life force

animated inert matter in neo-vitalist dogma so Moore, in 1934, portrayed the

expressivity of sculpture as a quality that was innate and not dependent upon

mere similitude: ‘For me a work must first have a vitality of its own. I do not

mean a reflection of the vitality of life, of movement, physical action,

frisking, dancing figures and so on, but that a work can have in it a pent-up

energy, an intense life of its own, independent of the object it may

represent’.81 This neo-vitalist impression of ‘pent-up energy’ was deeply

connected to the spatial disposition of the object, how it kinaesthetically enlivened

the visual field. Asymmetry was central to this aesthetic for Moore as it

greatly increased the number of viewpoints from which a sculpture could be

apprehended, compelling the viewer to actively move around the object:

‘Sculpture fully in the round has no two points of view alike. The desire for form completely realized is connected with

asymmetry. For a symmetrical mass being the same from both sides cannot have

more than half the number of different points of view possessed by a

non-symmetrical mass’.82

Importantly, asymmetry was recognised by modernist

artists and critics as a morphological quality inherent to living organisms and

powerfully illustrative of nature’s formative principles. Indeed Moore often

spoke of how irregularity of form was a quintessential aspect of organic life:

‘Asymmetry is connected with the desire for the organic (which I have) rather

than the geometric. Organic forms though they may be symmetrical in their main

disposition, in their reaction to environment, growth and gravity, lose their

perfect symmetry’.83 Moore derived this opinion from experimental morphology in

which physical energies were seen to dynamically warp organic matter, like the

amorphous shapes of wind-carved sandstone, into lop-sided or asymmetrical forms.

D’Arcy Thompson wrote of how the distinct curvature of living form was the

product of surface tensions and the contractility of cytoplasmic structures

under the pressure of gravity or thermodynamic energies. This was particularly

evident in the case of the amoeba – a primitive, single-celled organism – which

he understood to be ‘the very negation of rest or of equilibrium [as the]

creature [was] always moving, from one protean configuration to another; its

surface tension [being] never constant, but continually [varying] from here to

there’.84 As the surface tension of the amoeba’s watery, protoplasmic membrane

was dynamically fluid, the tiny creature could never acquire symmetry; but,

instead, passed rapidly from one distended, bulbous shape to another. Indeed,

Thompson argued that, subject to extreme molecular forces, microscopic

structures were always in a state of disequilibrium, producing forms that ‘are

in continual flux and movement, each portion of the surface constantly changing

its form, passing from one phase to another of an equilibrium which is never

stable for more than a moment’.85 Owing to its perpetually mutable form, the

amoeba – and other cytoplasmic, unicellular beings – embodied for biophilic

modernists a dynamic process of vital activity or metamorphosis that, like the

creeping tendril of a germinating seed, powerfully symbolised life’s generative

energies.86 Bergson, for his part, testified to the value of the amoebic form

to neo-vitalist philosophy, remarking that its very volatility singled it out

as the living embodiment of the élan vital: ‘The amoeba deforms itself in

varying directions; its entire mass does what the differentiation of parts will

localise in a sensorimotor system in a developed animal’.87 Naturally enough,

the ballooning, asymmetrical swell of the unicellular form was a key component

of biomorphic modernism, forming an integral component of what Alfred Barr

described – in decidedly amoebic terms – as ‘a soft, irregular, curving

silhouette half-way between a circle and the object represented’.88 He dubbed

this undulating, disproportionate contour the ‘Arp shape’, after the biomorphic

style of the German-French sculptor Hans Arp, which, he described as ‘a kind of

sculptural protoplasm, half-organic, half the water-worn white stone’ (fig.9).89 Among the modernists who Barr claimed

exploited Arp’s biomorphic idiom, Moore was prominent, representing a

biomorphic style that was ‘organic in form’.90 Developing this theme in 1943,

Grigson saw in Moore’s biomorphic semifigurations evidence of a deep interest

in the kind of single-celled or microscopic life that existed beneath the level

of consciousness, in the ‘rounded limbs of a human foetus, a fertilized egg, or

the heart of a water-flea, or even the pneumococcus that chokes and ruins the

lungs’.91

Throughout his life, Moore testified to the importance of science to

his practice and enjoyed the friendship of internationally renowned scientists

and engineers, such as the physicist Desmond Bernal and the zoologist Solly

Zuckerman.92 Of these relationships, perhaps the most telling was his

friendship with the evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley who, Moore claimed,

would ‘often drive out here [with his wife Juliette] with little bits of bones

or information. I mean they knew that I was very keen on bone structure, and

Julian asked me to go and see on one occasion the skull of an elephant, which

was the most wonderful sculptural object’.93 First broadcast in 1967, this

statement – made on the occasion of Huxley’s eightieth birthday – demonstrates

just how keenly biological theory and organic form continued to influence

Moore’s aesthetic philosophy until late into his career. Enthused by the

current of interest in biology and photomicrography that emerged within British

and European modernist circles in the 1930s, Moore revealed deep bioromantic

sympathies that enlivened his work from the 1930s onwards with vital rhythms

and organic imagery.94

B

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/edward-juler-lifeforms-henry-moore-morphology-and-biologism-in-the-interwar-years-r1151314

VIOLET TORSO ON ORANGE STRIPES - 1967

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 165 x 197 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Four Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 86

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING MOTHER & CHILD – 1974/76

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 213 cm

Material: Plaster

Catalogue Number: LH 649 primary

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation:

Gift of the Artist 1977, on Long Loan to the Dallas

Museum of Art

RECLINING FIGURES

WITH BLUE CENTRAL COMPOSITION - 1967

Artwork Type:

Graphics

Dimensions: Image:

283 x 197 mm

Material: Lithograph in Six Colours

Catalogue Number:

CGM 84

©

The Henry Moore Foundation

THREE RECLINING FIGURES - 1980

Artwork Type: Drawings

Dimensions: Paper: 231 x 180 mm

Paper/Support: Off - White Medium - Weight Wove

Catalogue Number: HMF 80(97)

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Acquired 1997

TWO RECLINING FIGURES IN YELLOW & RED - 1967

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 343 x 298 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Seven Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 73

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING FIGURE: ANGLES - 1979

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 218 cm

Material: Bronze

Catalogue Number: LH 675 cast a

Credit Line: Hakone Open-Air Museum, Japan

IDEAS FOR SCULPTURE: RECLINING MOTHER & CHILD -

1982

Drawings

Dimensions: Paper: 307 x 234 mm

Material: Charcoal,

Ballpoint Pen

Paper/Support: Cream Lightweight Wove

Catalogue Number: HMF 82(301)

Inscription: Ballpoint Pen l.l. Reclining Mother

& Child

Credit Line: HMF Enterprises

RECLINING FIGURE WITH CLIFF BACKGROUND - 1976

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 244 x 338 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Seven Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 436

© The Henry Moore Foundation

IDEAS FOR SCULPTURES - 1975

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 254 x 350 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Three Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 365

© The Henry Moore Foundation

PRELIMINARY IDEAS FOR UNESCO SCULPTURE, 1956

Gelatin Silver Print Mounted on Stock Card, Printed

Dimensions: 40 × 50.2 cm

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING WOMAN III - 1980/81

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 524 x 590 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Nine Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 593

© The Henry Moore Foundation

STONE RECLINING FIGURE WITH ARCHITECTURE BACKGROUND -

1979/80

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 991 x 1311 mm

Material: Etching,

Aquatint & Drypoint in Black

Catalogue Number: CGM 569

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING WOMAN I - 1980/1981

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 524 x 590 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Nine Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 591

© The Henry Moore Foundation

TWO PIECE RECLINING FIGURE NO:5 - 1963-64

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 243 x 373 x 165 cm

Material: Bronze

Catalogue Number: LH 517 cast 3

Credit Line: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek

THREE RECLINING FIGURE - 1975

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 130 x 188 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Six Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 420

© The Henry Moore Foundation

THREE RECLINING FIGURES - 1975

Artwork Type: Drawings

Dimensions: Paper: 263 x 217 mm

Paper/Support: Blotting Paper

Catalogue Number: HMF 75(8)

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Gift of the Artist

1977

THREE RECLINING FIGURES - 1976

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 462 x 385 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Six Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 438

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING FIGURE - 1966

Artwork Type: Drawings

Dimensions: Paper: 292 x 238 mm

Catalogue Number: HMF 3165

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Gift of the

Artist 1977

MOTHER &CHILD WITH DARK BACKGROUND - 1976

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 337 x 343 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Seven Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 434

© The Henry Moore Foundation

MAQUETTE FOR MTHER & CHILD: BLOCK SEAT - 1981

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 17.8 cm

Material: Plaster

With Surface Colour

Catalogue Number: LH 836

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Acquired 1993

RECLINING FIGURE - C.1972

Artwork Type: Drawings

Dimensions: Paper: 105 x 210 mm

Paper/Support: Cream Lightweight Wove

Catalogue Number: HMF 3448

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Gift of the

Artist 1977

RECLINING FIGURE - 1945

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 16.5 cm

Material: Bronze

Catalogue Number: LH 250 Cast hm

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Gift of the

Artist 1979

HALF FIGURE - 1930

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 49.4 x 35 x 23 cm

Material: Ancaster

Stone

Catalogue Number: LH 91

Credit Line: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne:

Felton Bequest 1948

STUDY FOR ‘ GROUP OF DRAPED FIGURES IN A SHELTER ‘ -

1941

Artwork Type: Drawings

Dimensions: Frame: 529 x 428 x 31 mm

Paper/Support: Cream Lightweight

Catalogue Number: HMF 1672

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Gift of Irina

Moore 1977

RECLINING FIGURE - 1939

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 27.9 cm

Material: Bronze

Catalogue Number: LH 202 Cast hm

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Acquired by

Exchange

With the British Council 1991

TWO RECLINING FIGURES - 1977/78

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 302 x 225 mm

Material: Etching

in Black

Catalogue Number: CGM 467

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING MOTHER & CHILD WITH BLUE BACKROUND - 1982

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 546 x 753 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Three Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 654

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RECLINING FIGURE 1945/1946

Private Collection

© Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore

Foundation

Tate Modern

THE OBSERVERS - 1981

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 225 x 251 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Six Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 626

© The Henry Moore Foundation

RED & BLUE STANDING FIGURES - 1950

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 305 x 235 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Two Colours

Catalogue Number: CGM 36

© The Henry Moore Foundation

THE THREE MARYS - 1981

Artwork Type: Graphics

Dimensions: Image: 225 x 251 mm

Material: Lithograph

in Eight Colours

Catalogue number: CGM 627

© The Henry Moore Foundation

MAQUETTE FOR RECLINING FIGURE: PROP - 1975

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 27.9 cm

Material:plaster

Catalogue Number: LH 676

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Gift of the

Artist 1977

RECLINING FIGURE - 1976

Artwork Type: Drawings

Dimensions: Paper: 176 x 254 mm

Paper/Support: Cream Lightweight Wove

Catalogue Number: HMF 76(19)

Inscription: Pencil u.l. Not in Artist's Hand 12

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Gift of the

Artist 1977

RECLINING WOMAN: ELBOW - 1981

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: Artwork: 221 cm

Material: Bronze

Catalogue Number: LH 810 cast 0

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Acquired 1986

SEATED FIGURE: ARMLESS - 1949

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 23 cm

Material: Bronze

Catalogue Number: LH 272a Cast hm

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Gift of the

Artist 1977

RECLINING FIGURE: SMALL HEAD - 1980

Artwork Type: Sculptures

Dimensions: 13.7 cm

Material: Bronze

Catalogue Number: LH 794 cast 0

Credit Line: The Henry Moore Foundation: Acquired 1986

ERICH

NEUMANN ON HENRY MOORE: PUBLIC SCULPTURE & THE COLLECTIVE UNCONSCIOUS BY

TIM MARTIN

The psychoanalyst Erich Neumann applied Carl Jung’s concepts about

the unconscious mind in his book on Moore’s sculpture, The Archetypal World of

Henry Moore (1959), in which he described the artist’s imagination as

essentially feminine. Although original and for a period influential, Neumann’s

ideas about sculpture remain today largely unexamined. The psychoanalytically

informed nature of many of the concepts we use today to discuss the aesthetics

and function of sculpture can be traced back to early and mid-twentieth century

critical debates that, inevitably given his stature, coalesced in some measure

around the work of Henry Moore. From the 1930s to the 1980s his sculptures were

the subject of discussion by a number of critics who, reflecting a widespread

fascination with such matters, took an active interest in psychoanalysis and

its application to art. These included such well-known figures as George

Wingfield Digby, Herbert Read, Adrian Stokes, David Sylvester and Peter Fuller.

Of all such writers, however, the Israeli psychoanalyst Erich Neumann

(1905–1960) provided perhaps the most thoroughgoing application of

psychoanalytic concepts to Moore’s work. In his lavishly illustrated book ‘ The

Archetypal World of Henry Moore ‘, published in 1959, Neumann (fig.1) hailed

Moore as a paragon of healthy modern psychical development and as an artist who

deserved the worldwide adulation he was receiving at the time. According to

Neumann, Moore was remarkable for being in touch with his ‘anima’, the feminine

side of his unconscious, and for heralding a new age based on a collective

archetype he called the ‘Great Mother’. Of Moore’s psychoanalytically

influenced critics Neumann was the most extensive in his claims and yet he

never met Moore. Read, Stokes and Sylvester knew Moore and shared a circle of

friends centred on the London art world; by contrast, Neumann’s views on the

artist were inspired by the writings of the Swiss psychiatrist and

psychotherapist Carl Jung (1875–1961). Despite being one of Jung’s most gifted

students, Neumann is a figure whose history is relatively little known,

particularly in art historical circles. This essay seeks to contextualise

Neumann’s views on Moore’s work in relation to his earlier writings on art and

the unconscious, and it traces his subsequent connections with the British art

world through Herbert Read. It then examines Neumann’s book in detail,

recording the responses to it by Moore and critics of the period, as well as

more recent authors. In conclusion, it reviews Neumann’s basic understanding of

sculpture and examines how it was adapted and modified by sculptors in the

1960s and 1970s in ways that demystified some of its more romantic claims.

ERICH NEUMANN & CARL JUNG

Seven years younger than Henry Moore, Erich

Neumann was born in Berlin in 1905 into a non-practicing Jewish family. He

attended university in Nuremberg, studying philosophy and psychology, including

the work of Freud and Jung. Neumann went on to

study medicine in Berlin but on completion of his

studies was denied an internship because of the race laws introduced by the

Nazi government.1 Neumann spent time writing poetry and a novel, and developed

his understanding of contemporary art and literature, notably the novels of

Franz Kafka. Married and with Nazis policing the streets of Berlin, Neumann

decided in 1933 to emigrate to Palestine. However, he travelled first to Zürich

where he met Jung, the founder of what was called analytic psychology (which

was distinct from the school of psychoanalysis established by Freud). Neumann

was twenty-eight years old, and Jung was thirty years his senior. Neumann

decided to stay in Zürich and enter analysis with Jung, while his wife Julia

entered analysis with Jung’s wife Emma.

In Zürich the Neumanns studied Jung’s

descriptions of the unconscious as a field of autonomous patterns of thought

and images, or ‘archetypes’. Variously framed by individuals and their

cultures, archetypes included, for example, the figures of the great mother and

the great father, events such as birth and death, and motifs such as the flood

or the apocalypse. In search of evidence to support his theories, Jung trawled

freely through a wide range of ethnographic and historical records, including

Sir James George Frazer’s ‘The Golden Bough ‘ (1890), the ancient Chinese

text I Ching and the esoteric teachings of the Kabbalah. In these he found what

he described as remarkable consistencies in human culture due to the

commonality of human instincts and received experience. Jungian therapy

involved identifying a person’s archetypes and helping them emerge through a

process of transformation, maturation and unification in the ‘self’ archetype,

the inner godhead.

After nearly a year of Jungian analysis and study, Erich and

Julia Neumann qualified as analysts. But he disagreed with his mentor on two

topics: the best way to resist antisemitism and the value of modern art. In

1932 Jung had criticised the work of Picasso, writing:

‘’ It is the ugly, the

sick, the grotesque, the incomprehensible, the banal that are sought out – not

for the purpose of expressing anything, but only in order to obscure; an

obscurity, however, which has nothing to conceal, but spreads like a cold fog

over desolate moors; the whole thing quite pointless, like a spectacle that can

do without a spectator. ‘’

He had continued by condemning

‘’ the man in

him [Picasso] who does not turn towards the day-world, but is fatefully drawn

into the dark; who follows not the accepted ideals of goodness and beauty, but

the demoniacal attraction of ugliness and evil. It is these antichristian and

Luciferian forces that well up in modern man and engender an all-pervading

sense of doom, veiling the bright world of day with the mists of Hades,

infecting it with deadly decay, and finally, like an earthquake, dissolving it

into fragments, fractures, discarded remnants, debris, shreds, and disorganised

units.2 ‘’

Perhaps

under Neumann’s influence, Jung backpeddled in a later version of the essay in

1934, the year Newmann finally emigrated to Palestine, but the damage was

done.3 To Neumann’s dismay, Jung’s comments were used to tar modern art with

the brush of psychosis.4 In 1937 – the year Neumann, then running a busy

practice in Tel Aviv, heard that his father had been beaten to death by the

Nazis – the German government organised an exhibition called ‘ Entartete Kunst

‘ (Degenerate Art), which sought to demonstrate that avant-garde art was a

product of sick minds and an unhealthy culture. During the war years Neumann

developed independent theories while maintaining a regular correspondence and

close intellectual rapport with Jung.

Published in 1948, Neumann’s first book,

‘ Depth Psychology and a New Ethic ‘ marked the beginning of his longstanding

interest in ethical matters. Mindful of the lessons of fascism and the war, he

argued that the individual can combat collective evil but, for this to happen,

the ego must give up its pretensions of innocence and facile victim psychology

and recognise its ‘shadow’ evil side. In particular, the book warned of the

dangers of projecting an inner unconscious evil onto others. Contemporary

utopian ideologies (Nazism, communism or Zionism) promised an ultimate good but

in pursuit of this good projected evil onto others (Jews, capitalists or Arabs)

and sanctioned horrible crimes. Newman, by contrast, called for new ethics that

would accept and explore the darker side of human beings and then seek to unify

the good and the bad aspects of the psyche. Jungians in Zürich and London criticised

the book but Jung himself invited Neumann to speak at the annual Eranos

lectures, held in the Swiss town of Ascona. (Eranos is a Greek word for an

un-hosted, egalitarian banquet to which every guest brings a different

contribution.) The series brought together speakers on psychology, philosophy,

mythology, comparative religion and science, and papers were published in the

Eranos Jahrbuch.5

Neumann followed his Eranos debut with a book that attempted

no less than the history of man’s psychological development. ‘ The Origins and

History of Consciousness ‘ (1949) suggested that the consciousness of

individuals and of the collective developed in parallel. Drawing on a range of

myths, Neumann found that most cultures produced a succession of archetypes intended

gradually to enhance individual self-awareness and maturity. Cultures also

developed psychologically, evolving from a collective tribal maternal archetype

to a paternal archetype, embodied in a prophet. This archetype eventually

became repressive and was replaced by a higher and more modern archetype based

on individual responsibility. Jung greatly approved of his colleague’s attempt

to explain the evolutionary significance and relationship of different

archetypes, and after his retirement in 1951, Neumann became the leading figure

of the Eranos group, speaking at every conference from 1950 to 1960.6 Neumann

became interested in how past historical archetypes might be understood and

used to encourage modern individual and collective maturation. His 1953 paper

‘The Importance of Earth Archetypes for Modern Times’ examined the

changing meanings of the Earth archetype from the

middle ages onwards.7 Neumann concluded that the recent re-emergence of the

Earth archetype, an image of one’s bond with the land, was crucial to the

religious sentiments of modern man. He noticed, for example, how his own

growing love of the Palestinian desert had matured his Zionist convictions.

Neumann later used ideas from this paper in his book on Henry Moore but even

more important ideas emerged in his next and most ambitious book,

THE GREAT

MOTHER: ANALYSIS OF THE ARCHETYPE ( 1955 )

Richly illustrated with hundreds of

photographs and drawings taken from the ethnographic collection of the Eranos

archivist Olga Frobe-Kapteyn, this study compared Neolithic, Egyptian, Greek,

Medieval and Renaissance myths and images of the feminine. For Neumann the

archetype of the feminine and the Great Mother were elemental images arising

from the unconscious, signalling, positively, release and growth, inspiration

and wisdom, and, negatively, retention and devouring, or expulsion and

rejection, as charted in a diagram (fig.2).8 Although the great mother was a

dangerously dual figure, Neumann argued that western monotheist cultures needed

to rediscover this archetype to counterbalance the dominant patriarchal

consciousness that, left unchecked, could descend into a brutal masculine

ethos, as seen in Hitler’s Germany. Briefly he mentioned Moore as an example of

a contemporary artist who invoked the mother and child archetype in his

sculptures. Neumann’s book on the great mother was well received at Eranos and,

in 1957, when Neumann and Jung determined the theme of ‘man and sense’ for the