JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: BOOM FOR REAL AT THE SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT

FEBRUARY 16, 2018 – MAY 27, 2018

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: BOOM FOR REAL AT

THE SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT

THE SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT

FEBRUARY

16, 2018 – MAY 27, 2018

Jean-Michel

Basquiat (1960–1988) is acknowledged today as one of the most significant

artists of the 20th century. More than 30 years after his last solo exhibition

in a public collection in Germany, the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt is

presenting a major survey devoted to this American artist. Featuring more than

100 works, the exhibition is the first to focus on Basquiat’s relationship to

music, text, film and television, placing his work within a broader cultural

context.

In the

1970s and 1980s, Basquiat teamed up with Al Diaz in New York to write graffiti

statements across the city under the pseudonym SAMO©. Soon he was collaging

baseball cards and postcards and painting on clothing, doors, furniture and on

improvised canvases. Basquiat collaborated with many artists of his time, most

famously Andy Warhol and Keith Haring. He starred in the film New York Beat

with Blondie’s singer Debbie Harry and performed with his experimental band

Gray. Basquiat created murals and installations for New York nightclubs like

Area and Palladium and in 1983 he produced the hip-hop record Beat Bop with

K-Rob and Rammellzee.

Having

come of age in the Post-Punk underground scene in Lower Manhattan, Basquiat

conquered the art world and gained widespread international recognition,

becoming the youngest participant in the history of the documenta in 1982. His

paintings were hung beside works by Joseph Beuys, Anselm Kiefer, Gerhard

Richter and Cy Twombly. Basquiat’s raw, vibrant imagery is matched by a

startling erudition, seen in the extensive fragments of bold, capitalized text

that abound in his works. These bear witness to his encyclopedic interests and

his experience as a young artist with no formal training. Basquiat maintained a

playful approach to language and rebelled against political indifference

through his searching texts.

This

exhibition at the Schirn traces Basquiat’s journey from his beginnings as an

artist to his early death, aged 27, in 1988. Thematic sections illuminate the

context in which his works were made and the story of their reception. It

discusses questions such as the role of SAMO© and the influence of Downtown New

York scene on Basquiat’s artistic development and the significance of his

interdisciplinary art production, which has seldom been considered before. At

the Schirn, an outstanding selection of paintings, drawings, notebooks and

objects by Basquiat are presented from public and private collections, together

with rare films, photographs, music and archive material, which capture the

range and dynamism of his practice over the years.

The

exhibition Basquiat. Boom for Real is made possible by the Art Mentor

Foundation Lucerne.

“Basquiat’s

myth still overrides the scientific examination of his artistic oeuvre. And

frequently the historic and cultural context in which his unusual works were

created is neglected as well. The exhibition Basquiat. Boom for Real starts out

from this premise, demonstrating the vitality and diversity of the artist’s

entire oeuvre and telling of the wide-ranging influences. Because Jean Michel

Basquiat’s art is closely linked with life itself: social, political and

art-historical subjects flow together in his work. It is a mixture which

dissolves the boundaries of the disciplines and those of his own identity. More

than 30 years after Basquiat’s last solo presentation in a public collection in

Germany, the Schirn is dedicating a major overview exhibition to his oeuvre. It

is a unique event”, comments Dr. Philipp Demandt, the Director of the Schirn

Kunsthalle Frankfurt.

Lisane

and Jeanine Basquiat, the artist’s sisters, on the exhibition: “If you want to

know what there is to know about Jean-Michel, the place to go is to his work.

Presenting it now to the public both in London and Frankfurt in this major

survey is a great opportunity and very special to us”.

ARTWORKS

AND SUBJECTS OF THE EXHIBITION

At the

beginning of his artistic career, Basquiat created politically charged

graffiti. In 1978, at the age of seventeen, he and his high-school friend Al

Diaz operated under the pseudonym SAMO©, writing cryptic statements in black

capital letters on the walls of buildings in New York. The graffiti were

satirical attacks on the banality of American culture; their playful and

rhythmical use of language soon made them unmistakable. This exhibition at the

Schirn presents a large number of photographs by Henry Flynt, who documented

this period. The staging within what was then the new artists’ district of SoHo

was decisive for the success of SAMO©. Papers such as the SoHo Weekly News and

the Village Voice started campaigns to reveal the identity of SAMO©.

Basquiat

had a sense of humour about his status as an artist. He was an autodidact who

left school at the age of 16 and who never had any formal art training. Growing

up in a cultured Brooklyn family, he regularly visited the New York museums as

a child. He owned a comprehensive collection of artist’s monographs which he

used as sources. Even in his earliest paintings and drawings Basquiat showed

that he knew how to borrow from the visual vocabulary of twentieth-century

Western painting, while developing a style distinctively his own.

Basquiat

achieved his breakthrough with the presentation of his works in the group

exhibition at P.S. 1 New York/New Wave. Works such as Untitled (1980) – a sheet

of metal over two metres high with spray-painted text: NEW YORK NEWAVE – are

brought back together again at the Schirn for the first time since their

original display. The enthusiasm of his contemporaries and the encouragement

Basquiat received from his fellow-artists and critics can be experienced to

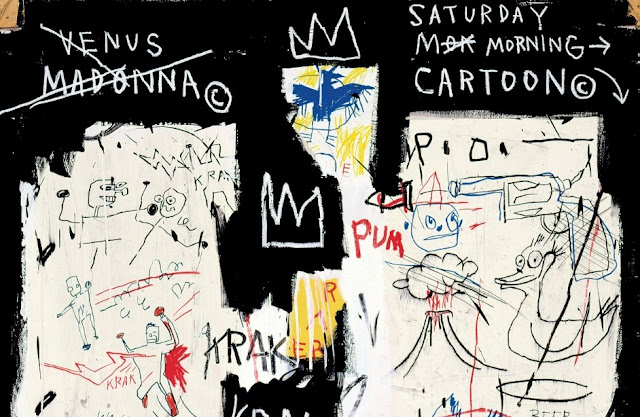

this day. The works from his first solo exhibition in 1982 were full of

explosive energy – layers of paint in intensive shades and scribbled, scratched

arcs which resemble the movement lines in action cartoons. The Schirn also

presents works from this period including Untitled (1982) showing a victorious

boxer with his fists raised and a thorny halo.

Basquiat

was not only a painter and graphic artist; he was also a performer, actor,

poet, musician and DJ. He was thus a direct disciple of the collective

tendencies of the international art scene of the 1970s and early 1980s to work

in a multidisciplinary way. Together with Michael Holman, Vincent Gallo and

Nicholas Taylor, Basquiat played clarinet and synthesizer in the band Gray.

Jazz and blues play an important role in his oeuvre. In many paintings he

studied the history of black jazz musicians – as, for example, in the work King

Zulu (1986). He was an early protagonist of the hip-hop movement alongside Fab

5 Freddy, Toxic and Rammellzee. Under his own label Tartown he produced the

record Beat Bop (1983), for which he also designed the cover. In the

independent film New York Beat written by Glenn O’Brien (later released as

Downtown 81), Basquiat was chosen for the main role and played the artist he

would later become. The exhibition in the Schirn brings this era to life once

more with the films New York Beat (1980-81), excerpts of Basquiat’s appearances

in the programme TV Party (1979–1982) as well as photographs of key figures

from the Downtown scene such as Madonna, Debbie Harry, Grace Jones, Maripol and

Andy Warhol. In the early 1980s Basquiat produced numerous collages, postcards

and objects together with Keith Haring, Jennifer Stein, John Sex and others.

The exhibition also shows a refrigerator Untitled (Fun Fridge) (1982) and a

vase – also Untitled from 1982. On the initiative of Bruno Bischofberger,

Basquiat made the acquaintance of Andy Warhol; they would create a series of

joint works with Francesco Clemente. Basquiat and Warhol continued to cooperate

between 1984 and 1985. The Schirn presents their collaborative piece Arm and

Hammer II (1984) as well as and the double portrait Dos Cabezas (1982), which

Basquiat painted immediately after his first meeting with Warhol.

Basquiat

drew from his surroundings and experimented with different supports and

materials. In the style of copying and pasting foreign content he took over

material he had found and changed it to suit his sense of aesthetics. His

approach was based on the cut-up technique of the Beat authors who experienced

a revival during the early 1980s. He structured the picture surface with the

conventions of quotations – footnotes, numbers, indexes – as well as grids,

lines and vectors which recall mind maps and flow diagrams. His particular

preference lay in the schematic representation of complex interconnections –

from Leonardo da Vinci’s codices to star charts to illustrations from

encyclopaedias and reference works. It was here that Basquiat found the raw

material for his art. He referred repeatedly in his works to those of famous

artists, including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Titian and Leonardo da Vinci.

The Schirn is also presenting his works Untitled (Pablo Picasso) (1984) and

Leonardo da Vinci’s Greatest Hits (1982). Basquiat recorded his thoughts and

ideas in lined notebooks. The exhibition has assembled a selection of these

books with poems, sketches, quotations, text fragments and addresses which

served as both diaries and sources of inspiration. Exhibition curated by

Barbican Centre, London, in cooperation with the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

http://www.schirn.de/en/exhibitions/2018/basquiat/

JEAN MICHEL BASQUIAT & ANDY WARHOL, ARM &

HAMMER II, 1984

Acrylic on Canvas

Guarded by Bischofberger, Männedorf-Zurich,

Switzerland,

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 & The Estate of

JeanMichel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar,

New York, Courtesy Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Männedorf-Zurich, Switzerland

New York, Courtesy Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Männedorf-Zurich, Switzerland

The

joint work “Arm and Hammer II” was created in 1984. Warhol began with two

reproduced logos of “Church & Dwight”, an American manufacturer of

household consumer products. This logo was developed in the early 1960s and

took up the traditional manner of depicting Vulcan with the motif of a muscular

arm: The Roman god of fire, metalworking and the forge was frequently portrayed

in visual arts as a blacksmith with a hammer. In the same way that “Church

& Dwight” had appropriated this motif for marketing purposes, Warhol

removed it from its customary context. Greatly enlarged, it perhaps symbolizes

the strong influence of large corporations on American consumer culture.

Basquiat responded to Warhol’s initial work by placing the black censured strip

across the brand name of the left-hand logo. He covered the arm-and-hammer

symbol in the center with the depiction of a black saxophonist. The musical

instrument thrusts itself over the logo into the empty picture space, followed

by large blue dots – a sign that the pulsating energy of Jazz would not be

halted. The number “1955” alludes to the legendary Jazz musician Charlie

Parker, who died in that year. In this manner Basquiat confronted his hero with

Vulcan, effectively making them equals. Simultaneously, this juxtaposition can

be read as criticism of the commercialization of Jazz.

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/collaborations

GLENN, 1984 ( DETAIL )

FIVE FISH SPECIES 1983

BASQUIAT. BOOM FOR REAL, EXHIBITION VIEW,

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2018, Photo: Norbert

Miguletz,

Artworks: © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 & The Estate of Jean-Michel

Basquiat,

Licensed by Artestar, New York.

GLENN, 1984

Acrylic, Oil Stick and Photocopy, Collage on Canvas

Private collection, © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, MOSES AND THE EGYPTIANS, 1982

© The Estate of Jean Michel Basquiat. Licensed by

Artestar, New York.

Courtesy FMGB Guggenheim Bilbao Museo, 2018 Photo by

Erika Ede

SUBSTITUTE

RELIGION

The

very title of the piece “Moses and the Egyptians” addresses one of the

best-known scenes from the Old Testament. The form of the twin rounded tops

brings to mind the classic depiction of the stone tablets that Moses brought

back down with him from Mount Sinai. Lines of text reference the Ten Plagues

and the meeting between Moses and the Pharaoh, which occurred prior to the

Israelites’ “Exodus from Egypt”. The religious context in this piece is not an

isolated case; indeed, in his notebooks Basquiat additionally termed some of

his poems “Prayers” or “Psalms”. This might be an expression of religiosity,

but Basquiat also associated psalms and prayers in his notebooks with music and

singing.

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/an-open-book

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2018, Photo: Norbert

Miguletz, Artworks: ©VG Bild-Kunst

Bonn, 2018 & The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Bonn, 2018 & The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Pablo

Picasso was a great source of inspiration for Basquiat. Here he portrayed the

Spanish artist in angular shapes, with a youthful face and wearing a

red-and-white striped pullover. He painted the name “Pablo Picasso” in capitals

seven times on the canvas. While the Spaniard’s face appears youthful, the red

striped pullover evokes associations with the photos of Picasso as an old man –

a reference to the artist’s long career. Picasso’s wild hair and facial

features bear a certain similarity to Basquiat himself. Did the young black

artist want to compare his own success with that of Picasso? The portrait can

be seen as a kind of self-assertion by Basquiat and refers to the position he

sought to occupy in an art world dominated by white artists.

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/place-to-be

UNTITLED ( PABLO PICASSO ), 1984

Oil, Acrylic and Oil Stick on Metal

Private Collection, Italy,

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 & The Estate of

Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Licensed by Artestar, New York

BASQUIAT. BOOM FOR REAL, EXHIBITION VIEW,

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2018, Photo: Norbert

Miguletz, Artworks:

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

This painting

with its numerous splashes and stains seems to have been realized quickly.

Three simply sketched mask-like heads dominate the picture surface. Basquiat

drew his inspiration for this work from many different sources: Next to the

head on the left, the name “ARRON” is scribbled, which is repeated as “ARON”

next to a crown in the center of the picture. In this we can see a reference to

the legendary baseball player Hank Aaron, whom Basquiat so admired. Presumably,

the artist was also alluding to the figure of Aaron from the Old Testament:

Moses’ brother, who played an important role in freeing the Israelites from

Egypt. The biblical reference is reinforced by there being three heads, which

could be a symbol of the Trinity. In this context the “A” and “O” letters

strewn here and there could be read as a reference to the famous verse from

Revelations in the New Testament: “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the First and

the Last, the Beginning and the End” (Rev. 22:13).

BASQUIAT. BOOM FOR REAL, EXHIBITION VIEW,

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2018, Photo: Norbert

Miguletz, Artworks:

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, UNTITLED, 1981 ( DETAIL )

BASQUIAT. BOOM FOR REAL, EXHIBITION VIEW,

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2018, Photo: Norbert

Miguletz, Artworks:

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, UNTITLED, 1981 ( DETAIL )

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, UNTITLED, 1981

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Rammellzee vs. K-Rob, produced and with cover artwork

by

Jean Michel Basquiat, ‘Beat Bop’, 1983

Vinyl Record and Slip Cover

Collection of Jennifer Von Holstein, © VG Bild-Kunst

Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New

York

BEBOP

MEETS HIP-HOP

A defining music style in the 1980s in New York was

Hip-Hop, which originated in African-American Funk and Soul music. Basquiat

worked regularly as a DJ and was one of the early actors in the Hip-Hop

movement. In 1983 he produced a Rap single with musicians Rammellzee and K-Rob:

Not only was “Beat Bop” released under Basquiat’s own label “Tartown”, but he

also designed the cover. The allusion to Bebop and its influence on the music

scene of the time could not be clearer. Some 500 records were initially

pressed, and today they are considered to be collector’s items amongst Hip-Hop

LPs.

YOU MAY LISTEN MILES DAVIS & MARCUS MILLER ''SIESTA'' ALBUM

You May Visit Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt Web Page to Explore

Jean Michel Basquiat's Individual Music Selection ....

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, UNTITLED (ESTRELLA), 1985

© The Estate of Jean Michel Basquiat. Licensed by

Artestar, New York.

Foto: Kent Pell. Courtesy Aquavella Galleries

This picture shows how Basquiat explored his fascination with

Bebop in his own works. Several simply sketched record outlines with the word

“DIAL” refer to Charlie Parker’s sessions at the eponymous record label between

1946 and 1947. The lists on the left-hand side of the work consist of titles

from the famous Savoy Studio recordings of 1945, including “NOW’S THE TIME” and

“THRIVING ON A RIFF”. There are also other musical references, for instance to

Jazz drummer “MAX ROACH”, the record label “SAVOY” and the record speed “78”.

The recurring expression “SO BE IT” may be a reference to the Blues song with

that title by Dean Elliott, who composed the music for Basquiat’s favorite

cartoon series “Tom and Jerry”.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, King Zulu, 1986, Acrylic, wax and

felt-tip pen on canvas, MACBA Collection. Government of Catalonia long-term

loan. Formerly Salvador Riera Collection, © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 & The

Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York, Photo: Gasull

Fotografia

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/the-colors-of-jazz

UNTITLED ( CROWN ), 1982

Acrylic, Ink and Paper Collage on Paper

Private Collection, © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, UNTITLED (CHARLES DARWIN), 1983

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

AN OPEN

BOOK

Basquiat

was an avid reader. The floor of his studio was strewn with books. Every visit

to the Strand Bookstore on Broadway brought new additions to his extensive

collection.

In

particular, it was in encyclopedias and reference books that Basquiat found the

raw material for his art. Like a sponge he soaked up the elements and symbols

he found in the knowledge they contained. In “Untitled (Charles Darwin)” he

processes scientific knowledge: the surface temperature of the sun, the theory

developed by Charles Darwin on the evolutionary descent of the various species,

and Gregor Mendel’s Laws of Heredity. Both scientists are represented in the

portrait and surrounded by several sets of text that allude to their

discoveries. Overall, the image resembles a mind map. It illustrates, through

the many crossings out, Basquiat’s thought and work process. He repeatedly made

references to the work of famous artists such as Picasso, Matisse, Titian or

Leonardo.

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/an-open-book

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT IN

COLLABORATION WITH FAB 5 FREDDY, FUTURA,

KEITH HARING, ERIC HAZE, LA

2, TSENG KWONG CHI,

KENNY SCHARF UND WEITEREN

KÜNSTLERN, UNTITLED, 1982

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by

Artestar, New York.

BASQUIAT. BOOM FOR REAL, EXHIBITION VIEW,

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2018, Photo: Norbert

Miguletz, Artworks:

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: LEONARDO DA VINCI’S GREATEST

HITS, 1982

© THE ESTATE OF JEAN-MICHEL

BASQUIAT. LICENSED BY ARTESTAR, NEW YORK.

phOTO: BRUCE M. WHITE. COURTESY ACQUAVELLA GALLERIES

phOTO: BRUCE M. WHITE. COURTESY ACQUAVELLA GALLERIES

In the picture Basquiat assembles views of bodies that can also be found in Leonardo da Vinci’s scientific studies. The individual elements have a sketched quality. One piece of writing on the work reveals that the drawing was inspired by Leonardo's study of the bone of leg in man and horse. Other sets of text describe body fragments and comment on individual elements of the picture.

UNTITLED, 1980

Enamel, Spray Paint and Oil Stick on Enamelled Metal

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Gift of an

Anonymous Donor,

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 & Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP,

Paris & The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat,

Licensed by Artestar, New York,

Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art

Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art

This work hung in P.S.1 right in front of the entrance

to the main exhibition. It took up the show’s slogan as its central theme with

its deliberately misspelt graffiti “

NEW YORK NEWAVE ”. Basquiat sprayed his work on a

metal panel. The picture shows a passing car and a plane in the

yellow sky – subjects that evoke acoustic associations and seem to transfer the

noise and energy of a city into the gallery. The scribbled letters “A”and “O” –

frequently employed by Basquiat – lend rhythm to the composition.

Hovering alongside the airplane, they resemble a blanket bomb

raining down on the car, possibly a reference to the air raids of World War II.

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, UNTITLED (ALICE IN WONDERLAND),

1983

©The Estate of Jean Michel Basquiat. Licensed by

Artestar, New York

IN

WONDERLAND

Alice

wanders through a world between reality and dream. Together with the surreal

figures, the young girl hears incredible stories. The animated world served

Basquiat as a source of inspiration and a projection surface for his own cosmos.

Basquiat’s

drawing “Untitled (Alice in Wonderland)” shows various characters from the

eponymous Japanese anime of 1983, e.g. the Cheshire Cat, the little blue Caterpillar

and the Mad Hatter. The artist brings the figures from the illusionistic TV

world into reality and assembles them again in a new context within his

picture. He originally created each sectionon a separate fragment of paper,

subsequently taping the various pieces together. The work illustrates a further

aspect of his working method, namely recombining existing elements.

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/the-screens

SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT

SCHIRN

KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT

The SCHIRN

KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT is one of most important exhibition venues in

Europe. Since opening in 1986, it has presented more than 200 exhibitions on

around 2,000 m² of floor space and can boast a total of more than 8 million

visitors. The SCHIRN focuses on art-historical and historico-cultural themes,

discourses, and trends from a contemporary perspective. Its range of offers

is multifaceted, international, and progressive; it attempts to open up

new points of view and to break open traditional patterns of reception. The

exhibitions are devoted in equal measure to contemporary stances in art and

art of the modern era.

PLACE OF EXCITING DISCOVERIES

The

SCHIRN strives to offer visitors an original, sensory exhibition experience

and opportunities for active involvement with the works on

display. This calls for modern and targeted education and communication

measures geared toward all age groups, such as a permanent games and learning

circuit, the MINISCHIRN, or the digitorial, an innovative way to prepare

oneself for visiting an exhibition. For years, the SCHIRN has also been a

pioneer in digital communication in the area of culture with its comprehensive SCHIRN MAGAZINE as well as with its multifaceted

activities on all of the social media channels.

The SCHIRN pushes space- and time-related boundaries, time

and again rethinks things, extends the exhibition space to include the

Internet, and provides exhaustive WIFI and progressive digital communication

offers free of charge. As one of the most outstanding art institutions in all

of Europe, it has also been a constant in Frankfurt’s cultural life, a place

were interested citizens, patrons and partners, young or established

artists, committed friends, as well as people from throughout the world come

together. The SCHIRN is not a temporary museum—not in terms of its

content-related orientation, presentation design, or its art-historical

approach. As an institution without a collection it is the SCHIRN's responsibility

to develop well-founded suggestions from a contemporary perspective. This

promotes a discourse that can be taken up again by museums.

The SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT has presented major surveys

dedicated to radical turn-of-the-century Austrian art, to pioneering artistic

positions ranging from Expressionism and Dadaism to the Surrealist object

art by Dalí and Man Ray, as well as dealt for the first time with female

artists of the Impressionist movement. The world of bohemian life in Paris

became visible in “Esprit Montmartre,” and “German Pop” demonstrated how

surprising the specifically German version of Pop Art is. Light was also shed

on sociohistorical and historico-cultural subjects such as “Shopping—A

Century of Art and Consumer Culture,” “Privacy,” the visual art of the Stalin

period, or New Romanticism in contemporary art; other presentations

revealed the influence of Charles Darwin’s theories on art of the nineteenth

and twentieth centuries, or the intriguing causalities between artists of

the modern era and self-proclaimed “prophets” of this period. Large-scale solo

exhibitions dealt with the oeuvres of artists such as Carsten Nicolai, Odilon

Redon, Edward Kienholz and Nancy Reddin-Kienholz, Edvard Munch, Jeff Koons,

Gustave Courbet, Yoko Ono, Théodore Géricault, Philip Guston, and Helene

Schjerfbeck. Jan De Cock, Jonathan Meese, John Bock, Mike Bouchet, Tobias

Rehberger, and Doug Aitken developed new exhibitions especially for the

SCHIRN.

http://www.schirn.de/en/m/schirn/

KIDS

JUST LOVE THE CHILDREN’S ART CLUB

Co-hosted

by the SCHIRN, Städel and Liebieghaus museums, the Children’s Art Club offers

children and youngsters aged between 6 and 13 the chance to explore these

museums, their exhibitions and not least their own artistic talents.

For just 20 euros a year club members enjoy unlimited

free admission to the SCHIRN and MINISCHIRN, the Städel and the Liebieghaus

and can take part in all public events, such as children’s and family guided

tours. In addition, the three museums will inform them in good time about

important dates and exciting activities on offer. And four times each year,

they get to take a peek behind the scenes at the SCHIRN, Städel and

Liebieghaus, finding out how paintings are attached to the wall, where the

lights are switched on, how artists go about their work, where the director’s

office is located and how a sculpture is restored. Exclusive events and

school sponsorships round out the program. Kindly sponsored by Fraport AG.

http://www.schirn.de/en/m/engagement/

SCHIRN

KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT

HISTORY AND FOUNDING

The

SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT was built at the edge of the historical path

between the Römer and the cathedral that future emperors ceremoniously

paced down on their way to their coronation in the Middle Ages. Butchers sold

their goods here at open stands, so-called “schrannen” or “schirnen”, to which

the SCHIRN owes its name. After World War II and the destruction of the historical

city in center 1944, the ensemble had disappeared. The area lay fallow for

nearly forty years until the SCHIRN complex, which was designed by the architects

Bangert, Jansen, Scholz & Schultes, filled the vacant lot between the Römer

and the cathedral. It is 140 meters long and only 10 meters wide and tall.

The

foyer of the SCHIRN is characterized by luminous walls that immerse the

space in alternating colors with the aid of RGB technology. Along with other

modernization measures, this design was developed in 2002 in collaboration

with the architectural office Kuehn Malvezzi in Berlin. The luminous walls

and the exhibition lighting were converted to LED in 2016 subject to

current climate

protection requirements and thus meet the newest standards.

OPENING OF THE SCHIRN

The

opening of the Kunsthalle coincided with a fertile period in terms of cultural

policy. “Culture for everyone” was the motto of Hilmar Hoffmann, who had a

formative influence on the city’s cultural life from 1970 to 1990 as its head

of cultural affairs. The foundation of the Museumsufer and the SCHIRN was a

result of his enthusiasm and creative drive. The latter was initiated for the

purpose of also being able to present “major exhibitions” in Frankfurt. The

SCHIRN’s founding director, Christoph Vitali, who served from 1986

to 1994, quickly understood to focus this vague purpose, which was as

open to interpretation as it was malleable. From the very beginning, Vitali

presented an extraordinary program radiating far beyond the city. From 1994

to 2001, Hellmut Seemann, Christoph Vitali’s successor, demonstrated how to

maintain the Kunsthalle’s independence in an economically difficult situation.

STRIKE OUT IN NEW DIRECTIONS

Under

the directorship of Max Hollein, the years after 2001 were marked by the

development of a stringent profile for the SCHIRN. The program now came to

center on nineteenth- and twentieth-century and contemporary art. The character

of the presentation also changed, aimed at clearly distinguishing the

Schirn’s range of offers from those of the museum. The Schirn’s exhibitions

address a large public. The goal of being the region’s most popular institution

in terms of attendance has repeatedly been more than achieved, and especially

so in recent years. However, the SCHIRN’s success is not measured by visitor

numbers alone, but likewise by its ambitious program and the resonance it

leaves behind in the art world and in the public.

SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT

JAZZ,

BEBOP AND BASQUIAT

Entire series of reference works study which artist influenced

whom and how, and conversely who was influenced by what thing or person(s).

While English film composer John Powell responded to the question of whether

he listened to other film music with a simple “Ooh God, no!”, others have a

much more casual attitude when it comes to giving themselves over to foreign

influences. Like Jean-Michel Basquiat: Music was one of his most important

sources of inspiration. He is said to have had some 3,000 LPs in his record

collection alone. In fact, friends relate that he constantly had music playing

in his studio – and anyone who visits the exhibition “Basquiat. Boom for

Real” at the SCHIRN will, before entering the exhibition rooms, have heard

Jazz music and seen a film excerpt showing Basquiat dancing happily.

In

countless of his works one can discern direct references attesting to

Basquiat’s fascination for literature, the visual arts and science,

inviting to trace the source of these influences. In several works

explicit references can be found both to Jazz and famous musicians, which

point to Basquiat’s intensive occupation with this new style of American

music that emerged in the 20th century, and whose influence on subsequent

music must not be underestimated.

THE ORIGINS OF JAZZ

The

origins of Jazz date back to the end of the 19th and the early 20th century,

when above all musicians in the south of the United States created a new type

of music that drew on the Blues and Ragtime. With its special rhythmic and

harmony elements Jazz is often seen as the American pendant to European classical

music, although it cites both the European and African history of music. Similarly

to Blues and Ragtime, Jazz music was largely played, defined and advanced by

African-American musicians. New Orleans Jazz was followed by Dixieland Jazz,

then in the 1920s by Swing, whose typical beat can be specifically traced

back to African rhythm techniques. Louis Armstrong provided the definition

when stating: “If you don’t feel it, you’ll never know it.”

It was

through the dance music played by the large Swing orchestras of the 1930s and

1040s that Jazz finally came of age: Several musicians, amongst them Charlie

Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, Thelonious Monk and Max Roach,

who were bored with the ever identical sounds of swing music experimented

with more sophisticated rhythms. The harmonies became more complex, there was

greater emphasis on improvisation, the music ensembles became smaller.

Bebop was born, the main basis for Modern Jazz.

BASQUIAT'S HEROES

While

Jean-Michel Basquiat also hauled the heroes of the old Jazz onto his canvases

like Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke as in his work “King Zulu”, the

protagonists of Bebop feature repeatedly in his works. And although he

asserted that Miles Davis was his favourite musician, there is another

great artist cropping up again and again in his works: Charlie “Bird”

Parker. The special relationship Basquiat had to Parker also emerges in a

different context: In her book “Widow Basquiat” Jennifer Clement quotes the

artist as saying he would go mad if he didn’t hear Parker’s music every day. At

that time a whole crate full of Ross Russell’s biography on Charlie Parker

“Bird lives!” stood in Basquiat’s studio, and he happily gave his friends

copies.

It is also possible to draw interesting parallels between

Modern Jazz, in the styles of Bebop, Hardbop, Modal Jazz und Free Jazz, and

Basquiat’s preferred method: on the one hand, free improvisation and trying

out new means of articulation starting with an existing song or melody structure

and on the other the references to existing “facts”, as Basquiat called the

inspiration he took from books and then placed in a new context. Or there was

the conscious focus on the intellect: Bebop, which distanced itself clearly

from the danceability of Swing and whose more complex harmonies demanded more

careful listening, and no longer had anything in common with the “feeling”

Armstrong believed Swing hinged on.

On the other hand, we have Basquiat’s collages and works with

a heavy emphasis on text and symbols, works that can evidently never be

completely deciphered and often place at their centre the head, separated

from the body as a symbol for the reactionary. Or, as American author Greg

Tate asserted: “He belongs to a black tradition, well established by our musicians,

of making work that is heady enough to confound academics and hip enough to

capture the attention span of the Hip-Hop nation.” Not least of all, one

reason Basquiat felt so close to young Bebop musicians is that they were among

the first Afro-Americans to also receive recognition and admiration from

whites, even though this did not prevent them from being subject to constant

racist discriminations or animosities, a situation he was also familiar

with.

You may

watch ‘’ Radiant Child ‘’ movie of Jean Michel Basquiat and reach more articles

to read to click above link.

CABEZAS, 1982

Acrylic and Oil Stick on Canvas With Wooden Supports

Private collection, © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by

Artestar, New York

COLLABORATIONS

Basquiat

collaborated closely with other artists. With this approach he took up the

collective trends within the international art scene in the 1970s and early

1980s.

Artist

Jennifer Stein got to know Basquiat in April 1979 at the Canal Zone party in

the loft of British artist Stan Peskett. Basquiat and Stein quickly became

friends and began, at Basquiat’s suggestion, to produce postcards together.

They arranged four compositions on a sheet measuring 27.9 x 21.6 cm. Then they

photocopied it multiple times, used a spray adhesive to stick the sheets onto

card, and cut out the postcards for sale. The collages they created were

inspired by the rough atmosphere of New York: street refuse, newspaper

headlines, advertising and cigarette butts. Basquiat and Stein sold their

postcards on the street for one dollar each. They often stood directly in front

of the Museum of Modern Art, even though the security staff constantly chased

them away. In 1979 they met Andy Warhol as he was eating lunch in the WPA

restaurant in SoHo. Basquiat sold him one of his postcards depicting

sunglasses. He later recalled that it had taken 15 minutes for him to summon up

the courage to go in.

FRIENDS

LIKE ANDY

Basquiat

admired Andy Warhol. From 1983 the two were close friends and began a fruitful

collaboration.

When

the two artists met for the first time, Andy Warhol had long since been an icon

of the international art scene – he was one of the founders of Pop Art. He took

his motifs from everyday culture, the consumer world, and the mass media. In

addition, from the 1960s Warhol constantly widened his repertoire and ignored

traditional divides between the various disciplines. His spectrum ranged from

painting, graphic art, drawing, photography, sculpture and film through to

fashion, television, performance, theater, music, and literature.

On the initiative of art dealer Bruno Bischofberger, Basquiat

visited his great idol on October 4, 1982 in the “Factory”, Warhol’s studio and

meeting place for the artistic avant-garde. After the encounter Basquiat

hurried back to his own studio and painted the double portrait “Dos Cabezas”.

It depicts the two artists’ heads with an ironizing similarity – Warhol with

the disheveled wig, and Basquiat with shaggy dreadlocks. Simultaneously, the

young artist expresses his desire to be on a level with his role model. He had

the work sent over to Andy Warhol that same afternoon before it had even dried.

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/collaborations

BASQUIAT. BOOM FOR REAL, EXHIBITION VIEW,

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2018, Photo: Norbert

Miguletz, Artworks:

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

KING ZULU, 1986,

Acrylic, Wax and Felt-Tip Pen on Canvas

MACBA Collection. Government of Catalonia Long-Term

Loan.

Formerly Salvador Riera Collection, © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

Formerly Salvador Riera Collection, © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The

Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Licensed by Artestar, New York, Photo: Gasull

Fotografia

Seven elements hover against a blue background. On the left

we see a trombone player. In the center is a mask labeled “KING ZULU”, and

below it a large ornate “G” and the information “5542-A”. To the right we can

make out a trumpeter, a small saxophone player and an elegant male figure

wearing a hat. The final element is easily overlooked: Basquiat first painted

the sentence “DO NOT STAND / IN FRONT OF / THE ORCHESTRA” on the canvas and

then painted over it in blue. However, this sentence is crucial to understanding

the painting. The mask refers to American Jazz trumpeter and singer Louis

Armstrong riding on a float as “King of Zulu” during the Mardi Gras

celebrations in New Orleans in 1949. The letter “G” is the logo of record label

Gennett Records, which was hugely instrumental in disseminating Jazz music. In

the seated trumpeter the artist has combined the figure of two black musicians:

the body of Bunk Johnson and the head of Howard McGhee. The number “5542-A” by

contrast refers to the record “Sensation” by the American Jazz band “Wolverine

Orchestra”. If the key to the painting lies in the inscription painted over in

blue, then the section that is not painted over can be read as calling on the

viewer to look below the picture’s “surface” and embark on his own

investigation of the history of American Jazz music.

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT,

SELF-PORTRAIT, 1981

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

a

Basquiat

reduced this double self-portrait to the silhouettes of two black heads, both

sporting dreadlocks. He used bright red oil stick to outline the mouth and eyes

of the left head. By contrast, the mouth is missing altogether on the head on

the right. This self-portrait poses many questions. Does it show a split

personality searching for himself? While the name of tenor saxophone player Ben

Webster can be seen several times on the left side of the picture, on the right

side Basquiat placed song titles by composer and pianist Thelonious Monk. These

elements provide the key to understanding the self-portrait: Basquiat placed

himself alongside his heroes from the music world, but simultaneously alluded

to the poor recognition given to African-American artists.

Basquiat

painted this football helmet with white and blue paint and stuck his own hair

on it. He may have been inspired by the readymades of Marcel Duchamp. The

French artist declared everyday objects to be artworks after making minor

changes to them or simply placing them on a pedestal. In doing so, he offered

up for discussion mass-produced items as readymades, and opened up completely

new ways of understanding art. Duchamp’s influence on the post-1945 generation

of artists was ubiquitous. Basquiat created a series of football helmets which

he wore as performance props and which simultaneously referenced his interest

in the history of famous black athletes. On one of the helmets Basquiat wrote

the name “AARON” – a reference to baseball player Hank Aaron, as made

previously in “Untitled, 1981”.

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/place-to-be

UNTITLED, 1982

Acrylic and Oil on Linen

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, © VG

Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York,

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York,

Courtesy Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam,

Foto: Studio Tromp, Rotterdam

THE

COLORS OF JAZZ

There

are numerous references in Basquiat’s oeuvre to his comprehensive Jazz and

Blues collection. The artist owned over 3,000 records and even swapped his own

works for rare vinyl pressings. It was also his custom to listen to loud music

and dance while he painted.

In his

paintings Basquiat frequently addressed the history of black Jazz musicians,

such as his idol Charlie Parker. He greatly admired the musician’s biography

“Bird Lives! The High Life and Hard Times of Charlie ‘Yard bird’ Parker” (1973)

by Ross Russell, and even kept several copies of it in a box in his studio to

give to friends.

Parker’s

musical style was trailblazing for the development of Bebop, which replaced

Swing as the main style in the early 1940s and was the foundation for modern

Jazz. With Bebop, Jazz increasingly morphed from light music to an art form.

Moreover, Bebop put the spotlight clearly on black musicians, who played

brilliantly even though they had no musical training – for the self-taught

Basquiat surely an interesting aspect.

Typically,

the fundamental elements of Bebop are considered to be greater rhythmic freedom

for drums and bass, as well as a quick tempo. However, it was the so-called

cutting contests that really set it apart. One of the musicians would improvise

a solo and another musician would respond to it. Such exchanges were either of

a competitive nature or took the form of a dialog.

Among

those who frequented New York clubs to listen to the musical experiments of

Bebop were representatives of Abstract Expressionism such as Willem de Kooning

and Jackson Pollock. The defining elements of this art genre, emotion,

spontaneity and free expression, had a lot in common with the transient and

spontaneous improvisations of Bebop music. It also had a far-reaching influence

on the poets of the Beat generation. The musical liberty of Bebop and the

“speed” of modern life inspired representatives of this literary genre to

experiment with language and style.

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/the-colors-of-jazz

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT,

UNTITLED (FOOTBALL HELMET), CA. 1981–84

© The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York

BASQUIAT. BOOM FOR REAL, EXHIBITION VIEW,

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2018, Photo: Norbert

Miguletz, Artworks:

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 &

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York.

A PANEL OF EXPERTS, 1982

Acrylic, Oil Stick and Paper Collage on Canvas with

Exposed Wooden Supports & Twine

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Gift of Ira Young,

© VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 & The Estate of

Jean-Michel Basquiat,

Licensed by Artestar, New York,

A PANEL OF EXPERTS, 1982 ( DETAIL )

SELF – PORTRAIT, 1983

Oil on Paper and Wood

Collection Thaddaeus Ropac, © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018

&

The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by

Artestar, New York.

Courtesy Collection Thaddaeus Ropac, London

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT IN

COLLABORATION WITH FAB 5 FREDDY, FUTURA 2000,

KEITH HARING, ERIC HAZE, LA2, TSENG KWONG CHI,

KENNY SCHARF UND WEITEREN KÜNSTLERN, UNTITLED (FUN FRIDGE), 1982

KEITH HARING, ERIC HAZE, LA2, TSENG KWONG CHI,

KENNY SCHARF UND WEITEREN KÜNSTLERN, UNTITLED (FUN FRIDGE), 1982

©The Estate of Jean Michel Basquiat. Licensed by

Artestar, New York

a

Painted everyday items repeatedly crop up in Basquiat’s

oeuvre, such as refrigerators, shelves, stools and tables. He produced “Fun

Fridge” in 1982. Originally it belonged to the Fun Gallery, which was

opened in 1981 by Bill Stelling and actress Patti Astor. The refrigerator bears

the signatures of artists from the graffiti, Hip-Hop and downtown scene.

Basquiat can be identified as SAMO©, while Patti Astor stylized her name with a

star. We also find depictions of figures from popular children’s shows. Another

joint product of this cooperation was the impressive blue vase bearing a series

of drawings and lettering.

http://www.schirn.de/basquiat/digitorial/en/place-to-be

YOU MAY LISTEN MILES DAVIS ''SOLEA'' ALBUM BY SKETCHES OF SPAIN

You May Visit Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt Web Page to Explore

Jean Michel Basquiat's Individual Music Selection ....

THE FASCINATION OF UNKNOWN

WHAT LINKS JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, ALIAS SAMO©, AND

BANKSY? SCHIRN MAG ON THE TRAIL OF STREET ART IN NEW YORK AND LONDON. ( DECEMBER 2017 )

BY MARTHE LISSON

Jean-Michel Basquiat – or rather his oeuvre – is

currently on display in London’s Barbican Centre before coming to the SCHIRN in

February 2018. His images are hugely influenced by the graffiti aesthetic,

which is hardly surprising given that he started out with his Writings in the

New York of the 1970s, where graffiti was as much a part of the city as the

empty municipal coffers. Nevertheless, Basquiat did not produce complex (text-)images

like Lee, Futura2000, Fab5Freddy and other greats of that time. His were

plainly design aphorisms.

During the early 1980s graffiti spread from New York

City across the world, and now street art (graffiti is a form of street art)

is more popular than ever. Book stores stock volumes about street art alongside

monographs of Van Gogh and Monet. Similarly, street photography is now

afforded the same significance as Brassai and Bresson. We harbor a yearning

for what is raw, supposedly authentic – we want street credibility, in

contrast to that which is dictated by powerful institutions and media channels.

And – something that has not changed since Basquiat’s time – we also want a

touch of the mysterious.

ANARCHY AND REBELLION

One of the most popular, fascinating and mysterious

street artists of recent years is Banksy. His Pieces and Writings have made

headlines not only in London, but all over the world. To this day, it is still

not certain who is behind the pseudonym Banksy, and that makes him – anonymously

– and his works even more popular. After all, in the age of iPhones, etc.,

surreptitiously hanging one’s own work in the Tate Gallery, as Banksy did in

2003, has a touch of anarchy and rebellion. But a background in graffiti is

not the only thing that links Banksy and Basquiat.

In the late 1970s Basquiat teamed up with his friend

Al Diaz, and from 1977 they started working under the pseudonym SAMO© (a wordplay

on ‘same old shit’), spray-painting aphorisms on the walls of SoHo and the

Lower East Side. These were tough times for the city: New York itself was on

the brink of ruin and US President Gerald Ford refused to provide state aid

to save the city from bankruptcy. The crime rate had doubled.

THE SPRAY CAN AS A KIND OF WEAPON

Buildings burned nightly in the Bronx, set alight by

their owners who were no longer able to let or maintain them. New York was

full of graffiti – there was barely a train that was not coated in color.

Primarily these were Writings, whereby the text functiones as the central

motif of the picture, and often it would be the artist’s own name or pseudonym

that was spray-painted as artfully as possible. Many graffiti artists saw the

spray can as a kind of weapon. With their Pieces, they were able to draw attention

to themselves without standing directly in the limelight as a person. Their

images represented them in the public sphere. Artists like Lee then developed

their Writings further, away from the narcissistic spraying of their own names,

tackling political themes instead.

In this chaotic, graffiti-covered city, the aphorisms

of Basquiat and Al Diaz appeared reduced and minimalistic, and thus touched a

nerve. SAMO© became a sensation. The tone of SAMO© was different, incorporating

witty statements: SAMO© AS AN END 2 THE NEON FANTASY CALLED ‘LIFE’ or ANOTHER

DAY, ANOTHER TIME, HYPER COOL, ANOTHER WAY 2 ------------. The curiosity

surrounding SAMO© eventually become so great that on September 21, 1978, the

SoHo Weekly News launched an appeal for the artist to make himself known.

SAMO© IS DEAD

In the newspaper The Village Voice, which resonated

far beyond Greenwich Village, the author Philip Faflick wrote about SAMO©,

saying that New York had stopped paying any attention to its walls until something

new had appeared that fall. This article also revealed the identities of the

two artists Jean and Al. The collaboration between Jean and Al fell apart

shortly afterwards, Keith Haring gave a eulogy in Club 57, and SAMO© IS DEAD

appeared on the walls of SoHo in the aftermath.

Undoubtedly it is not only since Basquiat and SAMO©

that people have been captivated by the anonymous, the unknown and the mysterious.

These days it is particularly fascinating, since it is far from easy to

remain anonymous. Nevertheless, Banksy has managed it very well for years; a

master of this very art of anonymity. He is the internationally popular

street art artist of recent years, and that is undoubtedly not only down to

his creativity, but also because his identity has still not been revealed. He

became known for his black-and-white Stencils (graffiti spray-painted with

the help of a stencil), primarily in London and Bristol. Over the last few

years, however, Australia, Germany, the USA and many other countries have also

got “their” Banksy.

AN (UNOFFICIAL) COLLABORATION

After a new work of Banksy graffiti appeared in

Dover in May (the EU flag, from which a worker is chiseling out a star),

Banksy returned to London in September with two works – in time for the opening

of the Basquiat exhibition. Both works are painted directly on the external

walls of the Barbican Centre itself which, according to Banksy’s Instagram

account, has always been careful to remove graffiti immediately.

The first, smaller piece of graffiti shows a Ferris

wheel on which the seats or cars are replaced by the crowns that Basquiat so

frequently painted. Underneath the wheel people stand in line waiting for a

ride – a little sideswipe at the exhibition, perhaps? The second, life-size

picture is based on one of Basquiat’s best-known paintings, “Boy and Dog in a

Johnnypump”. Banksy has the figure searched by the city’s police and labels

the work as a portrait of Basquiat. Perhaps it’s a critical comment on the

fact that Basquiat was the first black artist in an art market otherwise dominated

by whites and that black people are still far more frequently victims of police

discrimination and violence – subjects that Basquiat tackled in many of his

works.

The motifs of Banksy’s street art are easy to understand,

and the social criticism or criticism of current politics is often bold.

This is another element of his popularity, as his works are not cryptic.

Banksy is there for all to see, and has something in his creative bag of

tricks for everyone. His approach is a stroke of genius, since regardless of

whether his works are big or small, he has still never been seen creating them

in the public space. Everything immediately finds its way onto YouTube and

Facebook, but not Banksy. This leads time and again to speculation that

Banksy is not acting alone and perhaps even has an entire workshop. Maintaining

anonymity was undoubtedly easier for Jean and Al.

The SAMO© aphorisms have long since

disappeared from the walls of New York, but they are not forgotten, since the

avant-garde artist Henry Flynt promptly began documenting them. Many of these

photographs, which number 57 in total, feature in the exhibition Basquiat.

Boom for Real. Although they are considerably younger, most of Banksy’s

London works have largely disappeared already too. Transience is the fate of

street art. There are still 15 Banksys to be seen, however, and a map shows

exactly where. And anyone wanting to experience more of the “Banksy spirit”

can now add the “Walled Off Hotel” in Bethlehem to their itinerary.

http://www.schirn.de/en/magazine/context/basquiat_banksy_the_fascination_of_the_unknown/

NEW YORK’S NEW WAVE

Jean-Michel Basquiat and the curator Diego Cortez met for the

first time at the Mudd Club in Downtown Manhattan in 1979. Two years later,

Cortez curated the group exhibition New York/New Wave at the city’s P.S.1.

The opening night saw the writing of art history: The exhibition was a blockbuster

success and opened up the New York art scene to the then 20-year-old Basquiat.

In its exhibition Basquiat. Boom for Real, the SCHIRN has reconstructed the

arrangement of the works from that time, true to the original.

Long

Island City, Queens, 1981. On February 15 the P.S.1, Institute for Art and

Urban Resources, Inc. – now the MoMA PS1 directed by Klaus Biesenbach –

launched the group exhibition New York/New Wave, curated by Diego Cortez. The

large rooms were full of people, the rush of visitors overwhelming, as people

waited in line for two blocks to see Cortez’s portrait of the underground art

and post-Punk scene of New York City. The exhibition drew more than 100 established

and less established artists, musicians, writers and filmmakers from the No

Wave scene, including Andy Warhol, Keith Haring and Nan Goldin, now well-known

greats in the art world. It also included Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was then

just 20 years old.

A FASCINATING PORTRAIT OF NEW

YORK CITY’S POST-PUNK PERIOD

The

walls were hung from ceiling to floor with works. Different media and styles

hung side by side, photography alongside graffiti, alongside drawings,

alongside objects. Basquiat was the sole artist to be prominently presented

with paintings. His works adorned the final exhibition room and captivated

the New York public with their new visual language.

The New

Wave, the experimental downtown culture of Manhattan, a symbiosis of music,

film, performance and art, reflected the pulse of the time, charging Cortez’s

exhibition with energy. The avant-garde movement was formed of a group of

creative, rebellious and self-taught artists – qualities that Basquiat was

also happy to use in describing himself. The interest in this frenetic and

socially critical art of the mid-1970s and early 1980s spilled over from the

streets into the galleries of New York.

DIEGO CORTEZ AND JEAN-MICHELS

BASQUIATS FIRST ENCOUNTER:

ON THE DANCE FLOOR OF THE MUDD

CLUB

It was

a time of rebellion, of experimentation and of artistic freedom. New York

may have been heading for bankruptcy, but the underground scene didn’t let

this spoil the mood. On the contrary: From this dearth it drew a creative

energy that captivated Diego Cortez, too. At that time the young curator was

spending a lot of time among the circles of No Wave filmmakers and musicians,

such as John Lurie, Scott and Beth B and Lydia Lunch. As a co-founder of the Mudd Club, which was originally intended as a Punk

club but whose rooms later served as exhibition spaces and gallery areas for

artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, Cortez met Basquiat on the

dance floor in 1979.

Fascinated

by his SAMO© works and convinced by his talent, he encouraged the penniless

young man, who was already popular within the scene, to paint and draw, to

create works of art and sell them. This gave Basquiat money to then be able to

afford the materials he needed. Cortez’s idea for his popular group exhibition

goes back to another exhibition, "The Times Square Show" in June

1980, which earned gushing praise on the title page of the Village Voice as

“the first radical art show of the eighties.” Inspired by the success of the

Punk portrait show, in which Basquiat had taken part along with Keith Haring,

among others, the curator decided to organize his own exhibition entitled

New York/New Wave.

ALWAYS WHITE WALLS WITH

WHITE PEOPLE DRINKING WHITE WINE

In the

documentary "The Radiant Child" made by Basquiat’s former girlfriend

Tamra Davis in 2010, Cortez explains his interest in the show, saying he was

tired of seeing white walls with white people drinking white wine. Inspired by

the idea and reliant on the money, Basquiat prepared for New York/New Wave by

producing more than 20 drawings and paintings in a very short space of time,

using a wide variety of surfaces: metal, rubber, paper, canvas and wood. He

made the entire exhibition space his own, using the full height and breadth

of the exhibition walls and positioning his 23 works in a syncopal rhythm,

with the aim of challenging visitors’ viewing habits and sharpening their

sense for something new.

In the

same breath, Basquiat also created the promotional signs for the exhibition.

These included the prominent Jimmy Best and the graffiti “NEW YORK NEWAVE”

sprayed onto a metal plate, which hung in the corridor close to the exhibition

entrance. He not only replaced the poster advertising, but ultimately even

advanced to the point of being the defining statement and trademark of the

event.

AN EXPLOSIVE SUCCESS WITH

RESONANCE

During

the exhibition period, one after another gallery owners and collectors like

Annina Nosei, Emilio Mazzoli and Bruno Bischofberger became aware of the young

Jean-Michel Basquiat, as the news spread like wildfire. At the time Nosei, a

gallery owner, was known for representing international contemporary

artists like Francesco Clemente, David Salle and Sandro Chia. She signed a

contract with Basquiat, donating not only paint and canvases, but also

providing the artist with the cellar of her gallery at 100 Prince Street in

SoHo so he could use it as a studio.

In

1982, in his first US solo exhibition at the Annina Nosei Gallery, Basquiat’s

works sold out in one night. This was followed shortly afterwards by a

successful solo exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles, West Hollywood,

as well as the ARTFORUM cover story The Radiant Child by writer and art critic

Rene Ricard. It was from that point that Basquiat’s career really took off. A

year later the painter went down in history as the youngest participating

artist in Documenta 7, and during the course of his life he became a cult

figure.

You may

watch ‘’ Radiant Child ‘’ movie of Jean Michel Basquiat and reach more articles

to read to click above link.