THE FONDATION BEYELER: A PASSION FOR ART

THE PERMANENT COLLECTION

THE

FONDATION BEYELER: A PASSION FOR ART

THE

PERMANENT COLLECTION

Hildy

and Ernst Beyeler’s collection of around 300 works by more than 70 artists

provides an extensive overview of classic modern and contemporary art. Starting

with late and Post-Impressionist works by Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh and

Claude Monet, it continues via Cubism with Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque to

other characteristic groups of works by Joan Miró, Piet Mondrian, Vasily

Kandinsky, Henri Matisse, and Paul Klee. American Expressionism is represented

by artists like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman. The collection’s time-frame

comprises works by Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer and Neo Rauch. Among the new

acquisitions are works by Louise Bourgeois, Lucio Fontana, Franz West, Philippe

Parreno, Felix González-Torres, Gerhard Richter and more. A number of

sculptures from Africa, Alaska and Oceania provide an exciting counterpoint to

the works of European and American origin.

The

collection was built up over more than fifty years, in parallel to the activities

of the Galerie Beyeler. Early on, Hildy and Ernst Beyeler started setting aside

works they could not or did not wish to sell. They held their first exhibitions

at the Galerie Beyeler in the 1940s with Japanese woodcuts, drawings by

Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists, and graphic works by

Toulouse-Lautrec. The gallery soon became known as a leading specialist in

modern art. The Beyelers’ successful activities as art dealers, for example

their purchase of Improvisation 10 , which Vasily Kandinsky painted in 1910,

laid the foundation stone for the present collection. Another important factor

was their personal relationship with a number of artists, for example their

friendship with Picasso, several of whose masterpieces can now be seen in one

of the main exhibition rooms at the Fondation Beyeler. Works by Picasso and a

group of works by Paul Klee are among those that determined the collection’s

character from the outset.

The

idea of setting up a non-profit-making foundation emerged in the 1970s, but did

not at first take concrete shape. All that Hildy and Ernst Beyeler wished to do

initially was to adorn their home with art and to keep some of their favourite

works for themselves rather than selling them. In 1989, at the invitation of

the Spanish Ministry of Culture, the previously unknown collection was publicly

displayed for the first time in the Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, where

it attracted international attention. Since then, the Beyelers have extended it

through carefully selected acquisitions.

The

Beyeler Collection’s distinctive character derives from its concentration on a

particular period. Thanks to its selectiveness and the high quality of the

exhibits, it represents more than merely the subjective viewpoint of a

collector, providing an impressive survey of 20th-century art.

Most of

the works in the Beyeler Collection are paintings but it also includes a few

sculptures. It ends with works by Baselitz, Kiefer and Rauch. Conceptual art,

the second main development in modern art, and more recent trends are

intentionally not represented in the permanent collection. Instead, they are

dealt

with in the context of temporary exhibitions designed to create a dialogue with

contemporary art and to make the museum a dynamic forum for the presentation of

artists’ ideas.

Another

priority of the Fondation Beyeler, alongside its permanent collection, its

architecture and its temporary exhibitions, is to teach visitors more about

art. Private and public guided tours and viewings of individual works are

organized. Events involving other artistic disciplines also serve to enhance

visitors’ appreciation of art. These events, which are very popular, add a

further facet to the comprehensive range of activities offered by the Fondation

Beyeler.

https://www.fondationbeyeler.ch/en/museum/

HENRI MATISSE

Nu Bleu I, 1952

Gouache Painted Paper Cut-Outs onPpaper on Canvas

Dimensions: 106.3 x 78.0 cm

Dimensions: 106.3 x 78.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Henri Matisse / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

HENRI MATISSE

Algue Blanche Sur Fond Rouge et Vert, 1947

Gouache Painted Paper Cut-Outs, Verso: Pencil Drawing

Dimensions: 52.5 x 40.5 cm

Dimensions: 52.5 x 40.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Henri Matisse / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

HENRI MATISSE

Nu Bleu, la Grenouille, 1952

Gouache Painted Paper Cut-Outs on Paper on Canvas

Dimensions: 141.0 x 134.5 cm

Dimensions: 141.0 x 134.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Henri Matisse / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

HENRI MATISSE

Océanie, le Ciel, 1946-1947

Screen Print on Unbleached Linen, Piece 4/30

Dimensions: 173.0 x 364.0 cm

Dimensions: 173.0 x 364.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Henri Matisse / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

SARAH MORRIS

Damselfly [Origami], 2009

Household Gloss Paint on Canvas

Dimensions: 289.0 x 289.0 cm

Dimensions: 289.0 x 289.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

© Sarah Morris / Foto: Robert Bayer

SARAH MORRIS

SARAH MORRIS

Banco Aliança [Rio], 2013

Household Gloss Paint on Canvas

Dimensions: 214.0 x 214.0 cm

Dimensions: 214.0 x 214.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

© Sarah Morris / Foto: Robert Bayer

FRANCIS BACON

Portrait of George Dyer Riding a Bicycle, 1966

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 198.0 x 147.5 cm

Dimensions: 198.0 x 147.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, BeyelerCollection

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved /

ProLitteris, Zürich /

Foto: Peter Schibli

FRANCIS

BACON: THE LOGIC OF SENSATION BY GILLES DELEUZE

Author’s

Preface to the English Edition:

Francis

Bacon's painting is of a very special violence. Bacon, to be sure, often

traffics in the violence of a depicted scene: spectacles of horror,

crucifixions, prostheses and mutilations, monsters. But these are overly facile

detours, detours that the artist himself judges severely and condemns in his

work. What directly interests him is a violence that is involved only with

color and line: the violence of a sensation (and not of a representation), a

static or potential violence, a violence of reaction and expression. For

example, a scream rent from us by a foreboding of invisible forces: "to

paint the scream more than the horror ..." In the end, Bacon's Figures are

not racked bodies at all, but ordinary bodies in ordinary situations of

constraint and discomfort. A man ordered to sit still for hours on a narrow

stool is bound to assume contorted postures. The violence of a hiccup, of the

urge to vomit, but also of a hysterical, involuntary smile Bacon's bodies,

heads, Figures are made of flesh, and what fascinates him are the invisible

forces that model flesh or shake it. This is the relationship not of form and

matter, but of materials and forces making these forces visible through their

effects on the flesh. There is, before anything else, a force of inertia that

is of the flesh itself: with Bacon, the flesh, however firm, descends from the

bones; it falls or tends to fall away from them (hence those flattened sleepers

who keep one arm raised, or the raised thighs from which the flesh seems to

cascade). What fascinates Bacon is not movement, but its effect on an immobile

body: heads whipped by the wind or deformed by an aspiration, but also all the

interior forces that climb through the flesh. To make the spasm visible. The

entire body becomes plexus. If there is feeling in Bacon, it is not a taste for

horror, it is pity, an intense pity: pity for the flesh, including the flesh of

dead animals ....

There

is another element in Bacon's painting: the large fields of color on which the

Figure detaches itself - fields without depth, or with only the kind of shallow

depth that characterizes post-cubism. These large shores are themselves divided

into sections, or crossed by tubes or very thin rails, or sliced by a band or

largish stripe. They form an armature, a bone structure. Sometimes they are

like a ship's rigging, suspended in the sky of the field of color, upon which

the Figure executes its taunting acrobatics.

These

two pictorial elements do not remain indifferent to one another, but instead

draw life from one another. It often seems that the flat fields of color curl

around the Figure, together constituting a shallow depth, forming a hollow

volume, determining a curve, an isolating track or ring at the core of which

the Figure enacts its small feats (vomiting in a sink, shutting the door with

the tip of its foot, twisting itself on a stool). This kind of situation finds

its equivalent only in theater, or in a Beckett novel such as Le Depeupleur -

"inside a flattened cylinder .... The light .... Its yellowness"2 —

or else it is found in visions of bodies plunging in a black tunnel [44]. But

if these fields of color press toward the Figure, the Figure in turn presses

outward, trying to pass and dissolve through the fields. Already we have here

the role of the spasm, or of the scream: the entire body trying to escape, to

flow out of itself. And this occurs not only in Bacon's sinks, but through his

famous umbrellas which snatch part of the Figure and which have a prolonged,

exaggerated point, like vampires: the entire body trying to flee, to disgorge

itself through a tip or a hole. Or else, on the contrary, it will flatten

itself and stretch itself into a thick mirror, lodging its entirety into this

width until it separates and dissipates like a lump of fat in a bowl of soup.

The Figures themselves always present scrubbed zones and blurred ones which

attest to this dissipation. As of 1978-9, we can speak of a few paintings —

still rare with Bacon — in which the Figure has in effect disappeared, leaving

a trace or a geyser, a jet of water [82], of vapor, sand, dust, or grass [see

86, 88, 97]. This new period, which seems so rich in possibilities for the

future, is an abstraction which is purely Bacon's. It consummates the double

motion, of the fields of color toward the Figure, and of the Figure toward the

fields.

Bacon

is a very great colorist. And with him, color is related to many different

systems, two most importantly one of which corresponds to the Figure/flesh, and

the other to the color field/section. It is as though Bacon has reassumed the

entire problem of painting after Cezanne. Cezanne's "solution" -

basically a modulation of color by means of distinct touches that proceed

according to the order of the spectrum - in effect gave birth or rebirth to two

problems: how, on the one hand, to preserve the homogeneity or unity of the

background as though it were a perpendicular armature for chromatic

progression, while on the other hand also preserving the specificity or

singularity of a form in perpetual variation? This was the new problem for Van

Gogh as much as for Gauguin - a problem with two pressing dangers, since the

ground could not be allowed to remain inert, nor could the form become murky or

dissolve into grisaille. Van Gogh and Gauguin rediscovered the art of the

portrait, "the portrait through color," by restoring to the

background vast monochrome fields that are carried toward infinity, and by

inventing new colors for the flesh that are "far from nature" -

colors that seem to have been baked in a kiln, and which rival ceramics. The

first aspect has not ceased to inspire experiments in modern painting: those

great, brilliant monochrome fields that take life not in variations of hue, but

in very subtle shifts of intensity or saturation determined by zones of

proximity. This would be Bacon's path: where these zones of proximity are

induced either by sections of fields of color, or by virtue of a white

stretched band or large stripe which crosses the field (an analogous structure

can be found in Barnett Newman). The other aspect, the colors of the flesh, was

to be resolved by Bacon along lines that Gauguin presaged: by producing broken

tones [tons rompus], as though baked in a furnace and flayed by fire. Bacon's

genius as a colorist exists in both of these ideas at once, while most modern

painters have concentrated on the first. These two aspects are strict

correlates in Bacon: a brilliant, pure tone for the large fields, coupled with

a program of intensification; broken tones for the flesh, coupled with a

procedure of rupturing or "fireblasting," a critical mixture of

complementaries. It is as though painting were able to conquer time in two

ways: through color as eternity and light in the infinity of a field, where

bodies fall or go through their paces; and in another way as passage, as

metabolic variability in the enactment of these bodies, in their flesh and on

their skin (thus three large male backs with varying chasms in value [63]). It

is a Chronochromie, in the spirit in which the composer Olivier Messiaen named

one of his works.

The

abandonment of simple figuration is the general fact of Modern painting and,

still more, of painting altogether, of all time. But what is interesting is the

way in which Bacon, for his part, breaks with figuration: it is not

impressionism, not expressionism, not symbolism, not cubism, not abstraction

.... Never (except perhaps in the case of Michelangelo) has anyone broken with

figuration by elevating the Figure to such prominence. It is the confrontation

of the Figure and the field, their solitary wrestling in a shallow depth, that

rips the painting away from all narrative but also from all symbolization. When

narrative or symbolic, figuration obtains only the bogus violence of the

represented or the signified; it expresses nothing of the violence of sensation

— in other words, of the act of painting. It was natural, even necessary, that

Bacon should revive the triptych: in this format he finds the conditions for

painting and for color exactly as he conceives them to be. The triptych has

thoroughly separate sections, truly distinct, which in advance negate any

narrative that would establish itself among them. Yet Bacon also links these

sections with a kind of brutal, unifying distribution that makes them

interrelate in a way that is free of any symbolic undercurrent. It is in the

triptychs that colors become light, and that light divides itself into colors.

In them, one discovers rhythm as the essence of painting. For it is never a

matter of this or that character, this or that object possessing rhythm. On the

contrary, rhythms and rhythms alone become characters, become objects. Rhythms

are the only characters, the only Figures. The triptych's function is precisely

to this point to make evident that which might otherwise risk remaining hidden.

What a triptych's three panels distribute in various ways is analogous to three

basic rhythms - one steady or "attendant" rhythm, and two other

rhythms, one of crescendo or simplification (climbing, expanding, diastolic,

adding value), the other of diminuendo or elimination (descending, contracting,

systolic, removing value). Let us consider every Bacon triptych: in any given

case, where is the attendant-Figure, where is the adjunctive or the reductive

Figure? A 1972 Triptych [70] shows a Figure whose back is

"diminished," but whose leg is already complete, and another Figure

whose torso has been completed, but who is missing one leg and whose other leg

runs. These are monsters from the point of view of figuration. But from the

point of view of the Figures themselves, these are rhythms and nothing else,

rhythms as in a piece of music, as in the music of Messiaen, which makes you

hear "rhythmic characters." If one keeps in mind the development of

the triptych, and this way Bacon has of effecting relationships between

painting and music, then one can return to the simple paintings. No doubt one

would see that each of them is organized as though a triptych, that each

already encompasses a triptych, each distributes rhythms, at least three, as

though so many Figures resonating in the field, and that the field separates

and unites them, superposes them, of a piece.

Note:

You may have to read whole book of Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation by

Gilles Deleuze. This part quoted by Gilles Deleuze book Preface of the English

edition.

FRANCIS BACON

Lying Figure, 1969

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 198.0 x 147.5 cm

Dimensions: 198.0 x 147.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved /

ProLitteris, Zürich /

Foto: Robert Bayer

FRANCIS BACON

Sand Dune, 1983

Oil and Pastel on Canvas

Dimensions: 198.5 x 148.5 cm

Dimensions: 198.5 x 148.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All Rights Reserved /

ProLitteris, Zürich /

Foto: Peter Schibli

FRANCIS BACON

In Memory of George Dyer, 1971

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 198.0 x 147.5 x 2.5 cm Triptychon

Dimensions: 198.0 x 147.5 x 2.5 cm Triptychon

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved /

ProLitteris, Zürich /

Foto: Robert Bayer

EDGAR DEGAS

Trois Danseuses (Jupes Bleues, Corsages Rouges), Ca.

1903

Pastel on Paper on Cardboard

Dimensions: 94.0 x 81.0 cm

Dimensions: 94.0 x 81.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Robert Bayer

EDGAR DEGAS

EDGAR DEGAS

Le Petit Déjeuner Après le Bain (Le Bain), Ca.

1895-1898

Pastel on paper on paper mounted on card

Dimensions: 82.5 x 79.0 cm

Dimensions: 82.5 x 79.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Robert Bayer

PAUL KLEE

Die Vase, 1938, 122 (J 2)

Coloured Paste on Jute on Second Jute Mounted on

Stretcher; Original Frame Strips

Dimensions: 88.0 x 54.5 cm

Dimensions: 88.0 x 54.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© Foto: Peter Schibli

PAUL KLEE

Wald-Hexen, 1938,

145 (K 5)

Oil on Paper on

Burlap

Dimensions: 99.0 x 74.0 cm

Dimensions: 99.0 x 74.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler,

Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© Foto: Robert

Bayer

PAUL KLEE

Aufgehender Stern, 1931, 230 (V 10)

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 63.0 x 50.0 cm

Dimensions: 63.0 x 50.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© Foto: Robert Bayer

PAUL KLEE

Ohne Titel [Gefangen, Diesseits - Jenseits/Figur], um

1940

Oil, Drawing With Coloured Paste on Burlap With a

Paste Ground Mounted on Burlap

Dimensions: 48.0 x 44.0 cm Originaler Bildträger; 55.2 x 50.1 cm Tiefe 2 cm

Dimensions: 48.0 x 44.0 cm Originaler Bildträger; 55.2 x 50.1 cm Tiefe 2 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© Foto: Peter Schibli

PAUL KLEE

Nach der Über Schwemmung, 1936, 7 (7)

Coloured Paste and Watercolour on Ingres Paper Mounted

on Cardboard

Dimensions: 47.9 x 62.6 cm

Dimensions: 47.9 x 62.6 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© Foto: Robert Bayer

PAUL KLEE

Zeichen in Gelb, 1937, 210 (U 10)

Pastel on Cotton on Coloured Paste on Jute Mounted on

Stretcher;

Original Frame Strips

Dimensions: 83.5 x 50.3 cm

Dimensions: 83.5 x 50.3 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

PAUL KLEE

Ein Weib für Götter, 1938, 452 (A 12)

Coloured Paste and Watercolour on Paper Mounted on

Cardboard

Dimensions: 44.3 x 60.5 cm

Dimensions: 44.3 x 60.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Robert Bayer

PAUL KLEE

O! die Gerüchte!, 1939, 1015 (CD 15)

Tempera and Oil-Colour on Jute

Dimensions: 75.5 x 55.0 cm

Dimensions: 75.5 x 55.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Peter Schibli

PAUL KLEE

MUMOM Sinkt Trunken in den Sessel, 1940, 301 (H 1)

Coloured Paste on Paper Mounted on Cardboard

Dimensions: 29.5 x 21.0 cm

Dimensions: 29.5 x 21.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Peter Schibli

PAUL KLEE

Schlamm-Assel-Fisch, 1940, 323 (G 3)

Coloured Paste and Chalk on Paper Mounted on Cardboard

Dimensions: 34.0 x 53.5 cm

Dimensions: 34.0 x 53.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Cantz Medienmanagement, Ostfildern

ROY LICHTENSTEIN

Girl With Tear III, 1977

Oil and Magna on Canvas

Dimensions: 117.0 x 101.5 cm

Dimensions: 117.0 x 101.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

ROY LICHTENSTEIN

Beach Scene with Starfish, 1995

Oil and Magna on Canvas

Dimensions: 300.5 x 604.0 cm

Dimensions: 300.5 x 604.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

ROY LICHTENSTEIN

MARK ROTHKO

Untitled (Plum and Dark Brown), 1964

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 236.5 x 212.5 cm

Dimensions: 236.5 x 212.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko /

ProLitteris, Zürich /

Foto: Robert Bayer

MARK ROTHKO

Untitled (Red-Brown, Black, Green, Red), 1962

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 206.0 x 193.5 cm

Dimensions: 206.0 x 193.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko /

ProLitteris, Zürich /

Foto: Peter Schibli

MARK ROTHKO

Untitled (Red, Orange), 1968

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 233.0 x 176.0 cm

Dimensions: 233.0 x 176.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko /

ProLitteris, Zürich /

Foto: Robert Bayer

MARK ROTHKO

Blue and Gray, 1962

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 193.0 x 175.0 cm

Dimensions: 193.0 x 175.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko /

ProLitteris, Zürich /

Foto: Robert Bayer

PAUL CÉZANNE

Sept Baigneurs, Ca. 1900

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 38.0 x 46.0 cm

Dimensions: 38.0 x 46.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Robert Bayer

PAUL CÉZANNE

PAUL CÉZANNE

La Route Tournante en Haut du Chemin des Lauves, 1904-1906

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 65.0 x 81.0 cm

Dimensions: 65.0 x 81.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Robert Bayer

CLAUDE MONET

La Cathédrale de Rouen: Le Portail (Effet du

Matin), 1894

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 107.0 x 74.0 cm

Dimensions: 107.0 x 74.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© Foto: Robert Bayer

CLAUDE MONET

Nymphéas, 1916-1919

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200.0 x 180.0 cm

Dimensions: 200.0 x 180.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© Foto: Robert Bayer

CLAUDE MONET

Nymphéas, 1916-1919 ( Detail )

CLAUDE MONET

Le Bassin aux Nymphéas, Ca. 1917-1920

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: Panel 3: 200.7 x 301.0 cm; Panel 2: 200.7 x 300.9 cm;

Dimensions: Panel 3: 200.7 x 301.0 cm; Panel 2: 200.7 x 300.9 cm;

Triptychon, je 200.7 x 301.0 cm; Panel 1: 200.6 x

300.7 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Robert Bayer

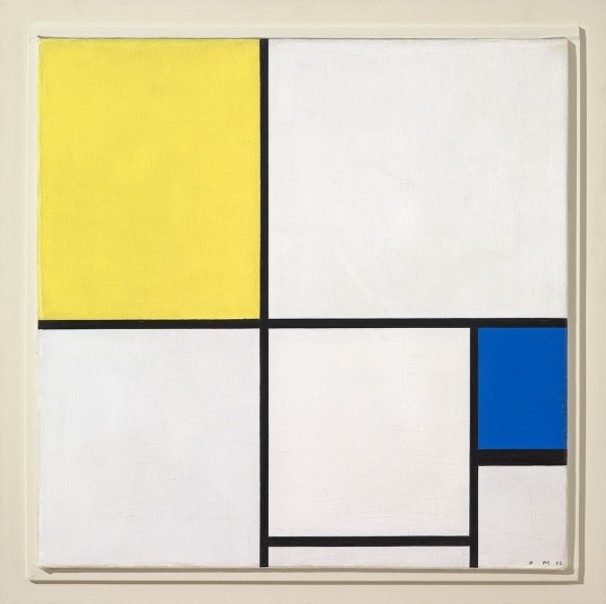

PIET MONDRIAN

Composition No. VI (Composition 9, Blue Façade), 1914

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 95.5 x 68.0 cm

Dimensions: 95.5 x 68.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

CH frei, © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR

International Warrenton,

VA USA / Foto: Peter Schibli

PIET MONDRIAN

Komposition mit Doppellinie und Blau, 1935

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 72.5 x 70.0 cm

Dimensions: 72.5 x 70.0 cm

Ohne Leisten und Grundplatte

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

CH frei, © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR

International Warrenton,

VA USA / Foto: Robert Bayer

PIET MONDRIAN

Rautenkomposition Mit Acht Linien Und Rot (Picture No.

III), 1938

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 100.5 x 100.5 cm; 103.0 x 103.0 cm

Dimensions: 100.5 x 100.5 cm; 103.0 x 103.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

CH frei, © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR

International Warrenton, VA USA /

Foto: Robert Bayer

PIET MONDRIAN

Komposition mit Gelb und Blau, 1932

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 55.5 x 55.5 cm

Dimensions: 55.5 x 55.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler;

Erworben Mit

Einem Beitrag von Hartmann P. und Cécile

Koechlin-Tanner, Riehen

CH frei, © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR

International Warrenton,

VA USA / Foto: Robert Bayer

PABLO PICASSO

Femme Assise (Dora), 1938

Pen and Ink, Gouache and Coloured Chalk on Paper

Dimensions: 76.5 x 56.0 cm

Dimensions: 76.5 x 56.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Peter Schibli

PABLO PICASSO

Femme Assise Dans Une Chaise (Dora), 1938

Pen and ink on Paper

Dimensions: 65.0 x 50.0 cm

Dimensions: 65.0 x 50.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Peter Schibli

PABLO PICASSO

Profil de Femme (Jacqueline), 1969

Linocut With Ink and Coloured Pen

Dimensions: 75.0 x 62.0 cm

Dimensions: 75.0 x 62.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

PABLO PICASSO

Mandoliniste, 1911

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 100.5 x 69.5 cm

Dimensions: 100.5 x 69.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

PABLO PICASSO

Le Sauvetage, 1932

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 130.0 x 97.5 cm

Dimensions: 130.0 x 97.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

PABLO PICASSO

La Femme Qui Pleure, 1937

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 55.0 x 46.0 cm

Dimensions: 55.0 x 46.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

PABLO PICASSO

Femme (Époque des "Demoiselles d'Avignon"), 1907

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 119.0 x 93.5 cm

Dimensions: 119.0 x 93.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

PABLO PICASSO

L'Enlèvement des Sabines, 1962

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 161.5 x 130.0 cm

Dimensions: 161.5 x 130.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

PABLO PICASSO

Vase de Fleurs Sur Une Table, 1969

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 116.0 x 89.0 cm

Dimensions: 116.0 x 89.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

PABLO PICASSO

2. PRIMITIVISM & CUBISM 1906

- 1915

Source: Oxford University Press

In his paintings immediately

prior to the early Cubist paintings of 1908, Picasso had initiated the

breakdown of illusionistic space that he was to pursue with an apparently

greater intellectual rigour through Cubism, a style that over the course of

a decade secured his prominent place in the history of 20th-century art. For

Picasso, however, the restraint of Cubism was preceded by works

exhibiting a raw intensity and violence in part stimulated by his reading of

non-Western art, and aligned with European currents of primitivism (see Primitivism, §2). This dialogue of apparently contrasting

positions, between the intellect and the emotions, between forms of classicism

and expressionism and between the conscious

and the unconscious, provided the dynamic of much of Picasso’s work.

Picasso and Fernande Olivier

spent the summer of 1906 in Gosol, a remote Catalan village in the Pyrenees

where he came to terms with his experience of Iberian sculptures from Osuna,

which he had seen in the Louvre in the spring. He began in his work to make

reference to forms of archaic art and to make expressive use of distortion with

insistently rhythmical repetitions and contrasts. In Gosol, Picasso made his first

carved sculptures. The resistance of wood produced simplified forms akin to

those in his paintings. Gauguin’s work in the same medium, the most immediate

European precedent available to Picasso, had been known to him through Paco

Durio, a previous tenant in the Bateau-Lavoir; its primitivism had been given

authority by the retrospective held at the Salon d’Automne in 1906, and it

offered access to another major stimulus, the art of the Pacific Islands. At

the same Salon ten paintings by the recently deceased Cézanne were exhibited.

Resolving his response to the achievements of these two artists preoccupied

Picasso over the next year and helped define his later work. On his return to

Paris, Picasso quickly completed his portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906;

New York, Met.; for illustration see Stein, (3)), which had

been left partly obliterated in the spring after over 80 sittings, giving her a

mask-like visage of monumental chiselled forms compressed within a shallow

space. The Stein portrait stands as a crucial shift from observation to

conceptualization in Picasso’s practice.

(I) ' LES DEMOISELLES D'AVIGNON '

The primitivism of Les

Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907; New York, MOMA) was more shocking still.

While it gestated from a series of preparatory drawings and underwent major

overpaintings during its production, it does not so much summarize Picasso’s

previous work as reframe his understanding of painting; he called it his ‘first

exorcism picture’. This radical picture, seen by friends in his studio and designated

by various appellations, was put aside and shown publicly only in 1916, when it

was given its present title by Salmon. It was purchased by the couturier

Jacques Doucet in 1924 and acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in

1939 at the time of Picasso’s retrospective. Embedded in its matrix are the

vestiges of Picasso’s encounters with 19th-century artists: Ingres, Manet,

Delacroix, Cézanne and Gauguin. Initially conceiving it as a narrative brothel

scene, Picasso changed it to a vertical format, adopted a more discontinuous

sense of space for the setting, removed the male visitors and reorientated the

women to confront the (implicitly male) viewer. Controversy surrounded its

stylistic disjunctures, confused by Picasso’s own equivocal statements. Rubin

(1984) has argued that Picasso reworked the painting in late June and early

July after a visit to the African and Oceanic collections in the Musée

d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. Although the painting has defeated most

efforts to specify African or Pacific sources, it records Picasso’s

reassessment of Gauguin’s primitivism and attests to the revelations accorded

by forms of non-Western carving in terms of conceptual principles of

representation and an emotively powerful evocation of magic and ritual. Linking

eroticism and the fear of death, the Demoiselles fixed an image that

was savage in style and violent in its dismemberment of the female body.

In paintings such as Mother

and Child (1907; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 19) and wood-carvings such

as Figure (1907; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 238), Picasso probed the

fetishistic and conceptually simplifying aspects of primitivism. Although the

juxtaposition of discordant elements in the Demoiselles gave way to

internal pictorial coherence, in general his work of the following year

displays an astonishing diversity of handling. Picasso sundered and isolated

illusionistic conventions, using bright hues contrasted with subdued greys and

earth colours, striated hatchings against angular crumpled planes, and rhythmic

repetitions paired with bar-like outlines. In still-lifes painted in spring and

summer 1908 and landscapes executed in August at La Rue-des-Bois, Picasso

continued to reflect on the work both of Cézanne, which he had studied in depth

at the retrospective held at the Salon d’Automne of 1907, and of Henri

Rousseau, whom Picasso and Olivier fêted with a banquet in November.

By October 1907, and probably

earlier in the spring of that year, Apollinaire had introduced Georges Braque

to Picasso. In the winter of 1908–9 Picasso repainted his monumental Three

Women (St Petersburg, Hermitage). Possibly in response to Braque’s

Cézanne-influenced landscapes from the summer, in this work and a number of

still-lifes Picasso imposed a more consistent control both on the surface and

on illusions of space, after the example of Cézanne but with a greater concern

for physicality. In contrast to Picasso’s usual assertive individualism, the

invention of Cubism was such a joint effort

that even he and Braque sometimes had difficulty in distinguishing each other’s

work; Braque later described their relationship as that of mountaineers roped

together.

You may

visit to read and see whole news to click above link about Pablo Picasso.

PABLO PICASSO

Nu Couché Jouant Avec un Chat, 10.5./11.5. 1964

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 114.0 x 194.5 cm

Dimensions: 114.0 x 194.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Succession Picasso / ProLitteris, Zürich

/ Foto: Robert Bayer

THE FONDATION BEYELER

THE

FONDATION BEYELER

THE

ARCHITECTURE

The

Fondation Beyeler consists of three parts: the Berower Park, acquired by the

Riehen authorities in 1976, the 18th-century Berower Villa, which houses the

restaurant and offices, and the museum recently built by Renzo Piano. In 1991,

the Genovese architect Renzo Piano–who was awarded the renowned Pritzker Prize

in 1998– was invited to develop an architectural concept for the Fondation.

Piano described the assignment as follows: “A museum should attempt to

interpret the quality of the collection and define its relationship with the

outside world. This means taking an active, but not an aggressive role.” Two

years later following a referendum held in Riehen, permission was given to

build the museum. Construction work began the following year and continued

until autumn 1997.

THE

MUSEUM BUILDING

The

elongated building covers the whole breadth of the narrow plot of ground

situated between a busy main road and a protected area of farmland. It combines

two contrasting motifs: long, solid walls and a light, apparently floating

glass roof. All the external walls are clad with red porphyry from Argentina.

The

building is supported by four 127 metre-long parallel load-bearing walls placed

at intervals of about seven metres. The two end façades are made of glass and

look out over the park. On the road side, the museum is completed by a

windowless wall that protects the building and on the inside of which the Art

Shop, cloakroom, toilets, etc. are located. Piano has described this wall as a

kind of “backbone” or “formative zone” from which the architecture of the whole

building develops. On the opposite wall there is a winter garden with a view of

the surrounding countryside.

Located

between the longitudinal walls, the exhibition rooms dedicated to the permanent

collection are arranged in a well-proportioned pattern that can be altered if

necessary. The rooms are not organised in any strict linear order, but visitors

feel a natural inclination to move in a certain direction. Another distinctive

characteristic of the Fondation Beyeler is the absolute serenity of the

exhibition rooms, which is unmarred by any technical or design details and is

enhanced by the sensitive interplay between the walls, the ceiling and the

light-coloured French oak floor.

About

one-third of the total exhibition space is reserved for temporary exhibitions

that are presented directly beside the permanent collection. A staircase in the

adjacent winter garden leads down to the museum’s lower level, where there is a

311 square metres multi-purpose room that can also be used for temporary

exhibitions.

A large

glass roof lets daylight into the whole building. Unlike conventional top

lighting, this roof allows the zenithal daylight to filter into the building’s

interior in its natural state instead of homogenising it and making it diffuse

and milky. There are also three systems with artificial light sources that

illuminate the rooms when there is insufficient light from outside. With his

museum for the Fondation Beyeler, Renzo Piano has created a building of

restrained elegance that serves art without being self-effacing. This

characteristic is discussed in detail in the book “Renzo Piano–Fondation

Beyeler. A Home for Art,” which places the building in the context of

international museum architecture. Basel’s international reputation as a centre

of fine architecture is considerably enhanced by the Fondation Beyeler.

THE

EXTENSION

Less

than two years after the Fondation Beyeler’s inauguration, the museum was

extended by 12 metres (between September 1999 and May 2000). The total

exhibition space was increased by 458 square metres to 3,764 square metres,

offering more flexibility for the organisation of exhibitions. Additional space

was created on the lower level for events, seminars, new media and offices. At

the same time, the museum’s grounds were extended to the north so that the

building now stands in the centre of them geographically as well as in other

respects.

http://www.fondationbeyeler.ch/en/Museum/Impressions/Architecture

THE FONDATION BEYELER

DIRECTOR SAM KELLER

THE FONDATION BEYELER

DIRECTOR SAM KELLER & ARVO PART

YOU MAY LISTEN ARVO PART - FRATRES

THE FONDATION BEYELER

ERNST BEYELER

THE FONDATION BEYELER DESIGN BY RENZO PIANO

THE FONDATION BEYELER

JOHN MIRO

1. LIFE & WORK - (I) CHILDHOOD AND WORK, TO 1919

Miró came from a family of craftsmen. His father

Miquel, the son of a blacksmith, was a goldsmith from the vicinity of Tarragona

in southern Catalonia; his mother, Dolors Ferrà, was the daughter of a

carpenter from Mallorca. He initially obeyed his family’s wishes that he follow

a business career by studying at the Escuela de Comercio in Barcelona from 1907

to 1910, but in 1911 an attack of typhus, coupled with nervous depression,

enabled him to abandon the course. He recuperated in his parents’ country house

at Montroig, south of Tarragona, a peaceful place to which he often returned in

later life and in which his artistic vocation and devotion to nature were

confirmed. Plants, insects, simple forms of life; the stars, sun, moon and sea,

especially the Mediterranean; the cultivated countryside itself, together with

elements of rural existence, all later found their way into his work.

In 1907 Miró began his artistic training in Barcelona

at the Escuela de Artes y Oficios de la Lonja, where Picasso had studied 12

years earlier; his teachers were Modest Urgell (1839–1919) and Josep Pascó

(1855–1910). In 1912 he entered the escuela de arte run by the great teacher

Francesc Galí (1880–1965), and there met the potter Josep Llorens Artigas, with

whom he formed a lifelong friendship. Galí noticed that Miró had an aptitude

for colour but difficulty in delineating shapes, and therefore blindfolded him

so that he would acquaint himself with the forms by touching them before

drawing them or modelling them in clay. Miró’s first paintings date from this

period, for example The Peasant (1914; Paris, Gal. Maeght, see 1981

exh. cat., p. 49). In 1915 Miró left the Escuela Galí and began attending

drawing classes at the Círculo Artístico de Sant Lluc, where Artigas was again

a fellow student and where he met Joan Prats (1891–1970), who became another

great friend. In 1918 Miró became one of the first members of the Grupo

Courbet, an association of artists founded by Artigas with other students from

Sant Lluc.

Between 1915 and 1918 Miró briefly painted in a manner

that he himself described as Fauve, using strong, bright colours. His

tendencies, however, to geometry, broad brushwork and a clarity of construction

distanced his work from the earlier movement. During this period he painted

figures, as in his portrait of V. Nubiela (1917; Essen, Mus.

Flkwang), as well as landscapes and views of villages in the province of

Tarragona, for example The Road from En Güell (1917; New York, MOMA).

1918 was a decisive year: Miró held his first one-man show in the Barcelona

gallery run by Lluís Dalmau, a key figure in the Catalan avant-garde, who in

1912 had dared to exhibit the Paris Cubist painters. It was vital to Miró’s

development that Barcelona was then a very lively cultural centre that attracted

foreign artists seeking refuge from World War I.

Miró remained faithful to the brilliance of colour of

his early work, but under the influence of Paul Cézanne and Cubism he

continued to emphasize the underlying construction of his pictures. In his

works of 1918 to 1922 he introduced a meticulousness and precision of drawing,

not out of an interest in illusionism or

in a slavish adherence to perceived reality but as a means of concentrating

attention on particular details. This new tendency is especially evident in

paintings such as Vegetable Garden with Donkey (1918; Stockholm, Mod.

Mus.) and Montroig, the Church and the

Village (1919; Spain, priv. col., see 1986 exh. cat. by R. S. Lubar and

others, no. 16). The self-portrait sometimes known as Young Man in Red

Shirt (1919; Paris, Mus. Picasso) and subsequent works, such

as Standing Nude (1921; Chicago, IL, Alsdorf Found.), display

a stylization and flatness, which can perhaps be traced to the Romanesque

paintings that had greatly impressed him in the Museu d’Art de Catalunya in

Barcelona. The general sense is of containment, as opposed to the almost

uncontrolled colour and violence of the previous period.

You may

visit to read and see more painting from John Miro to click above link.

JOAN MIRÓ

Peinture (Personnage: Les frères Fratellini), 1927

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 130.0 x 97.5 cm

Dimensions: 130.0 x 97.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Successió Miró / ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto:

Robert Bayer

JOAN MIRÓ

L'Étreinte du Soleil à L'amoureuse, 1952

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 22.0 x 16.0 cm

Dimensions: 22.0 x 16.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Successió Miró / ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto:

Peter Schibli

JOAN MIRÓ

Peinture, 1930

Oil, Charcoal and Plaster on Canvas

Dimensions: 231.0 x 150.2 cm

Dimensions: 231.0 x 150.2 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Successió Miró / ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto:

Robert Bayer

JOAN MIRÓ

Composition (Petit univers), 1933

Gouache on Card

Dimensions: 39.5 x 31.5 cm

Dimensions: 39.5 x 31.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Successió Miró / ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto:

Robert Bayer

JOAN MIRÓ

Danseuse Espagnole, 1945

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 146.5 x 114.5 cm

Dimensions: 146.5 x 114.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Successió Miró / ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto:

Robert Bayer

KASIMIR MALEWITSCH

Suprematistische Komposition, 1915

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 80.4 x 80.6 cm

Dimensions: 80.4 x 80.6 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Robert Bayer

MAX ERNST

Naissance D'une Galaxie, 1969

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 92.0 x 73.0 cm x 2 cm

Dimensions: 92.0 x 73.0 cm x 2 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Robert Bayer

SAM FRANCIS

Round the World, 1958-1959

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 276.5 x 321.5 cm

Dimensions: 276.5 x 321.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Peter Schibli

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

Isaku Yanaihara, 1961

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 100.0 x 81.0 cm

Dimensions: 100.0 x 81.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Peter Schibli

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

Grande Femme IV, 1960

Bronze, Piece 3/6; Inscription: "Susse Fondeur

Paris, Cire perdue"

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

Grande Femme III, 1960

Bronze, Piece 6/6; Inscription: "Susse Fondeur

Paris"

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

L'Homme Qui Marche Sous la Pluie, 1948

Bronze, piece 1/6; Alexis Rudier Fondeur, Paris

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

Femme Assise, 1949 - 1950

Bronze, Piece 2/6;

Inscription: "Susse Fondeur Paris"

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

Femme de Venise VIII, 1956

Bronze, Piece 6/6; Inscription: "Susse Fondeur

Paris"

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

Aïka, 1959

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 92.0 x 72.8 cm

Dimensions: 92.0 x 72.8 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Peter Schibli

VINCENT VAN GOGH

Champ Aux Meules de Blé, 1890

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 50.0 x 100.0 cm

Dimensions: 50.0 x 100.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Robert Bayer

VINCENT VAN GOGH

Champ de Blé Aux Bleuets, 1890

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 60.0 x 81.0 cm

Dimensions: 60.0 x 81.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© Foto: Peter Schibli

JEAN DUBUFFET: METAMORPHOSES OF LANDSCAPE

Landscape runs like a defining leitmotif throughout

Jean Dubuffet’s multifarious oeuvre. From his earliest phase right up to his

late period he constantly developed it in unexpected but consistent ways. The

retrospective at the Fondation Beyeler focuses on Dubuffet’s innovative concept

of landscape, which also served him as a springboard for addressing many other

subjects.

Dubuffet has often been quoted to the effect that

“Everything is landscape,” and landscape does indeed dominate his artistic

practice and ideas: in both, anything can metamorphose into landscape at any

time. It is this special capacity for metamorphosis, together with an intense

delight in experimentation, that singles out the multi-faceted character of

Dubuffet’s work. In his paintings, the shapes and textures of landscape can

emerge even from bodies and faces. His art is governed by a unique interaction

between nature and creatures that can even transform objects into landscape.

With Dubuffet a landscape is not, therefore, a faithful depiction of actual

appearances but their translation into mental images: landscape gives visible

form to the immaterial world inhabited by the human mind. Instead of seeking

beautiful idyllic landscapes, Dubuffet explores raw, naked earth, occasionally

reaching down into its geological substructure. Sometimes he will fashion his

landscapes and figures from actual natural elements, such as sand and gravel,

making them the real material of his pictures. Natural landscape becomes a free

and open field for artistic practice.

You may

visit to read and see more painting from Jean Dubuffet Exhibition news at

Fondation Beyeler to click above link.

JEAN DUBUFFET

Automobile à la Route Noire, 1963

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 195.0 x 150.0 cm

Dimensions: 195.0 x 150.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Peter Schibli

JEAN DUBUFFET

Ponge Feu Follet Noir, 1947

Oil on Canvas on Pavatex

Dimensions: 132.5 x 99.5 cm

Dimensions: 132.5 x 99.5 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Peter Schibli

JEAN DUBUFFET

Argument et Contexte, 1977

Acrylic on Glued Paper Mounted on Canvas (66 Sections)

Dimensions: 201.0 x 249.0 cm

Dimensions: 201.0 x 249.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

JEAN DUBUFFET

Site Avec Trois Personnages, 1974

Vinyl Paint on Cut-Out Pressed Wood

Dimensions: 269.5 x 446.7 cm

Dimensions: 269.5 x 446.7 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

JEAN DUBUFFET

Incitations Divergentes, 1976

Acrylic on Glued Paper on Canvas (28 Sections)

Dimensions: 173.0 x 291.0 cm

Dimensions: 173.0 x 291.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

JEAN DUBUFFET

Corps de Dame - Pièce de Boucherie, 1950

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 116.0 x 89.0 cm

Dimensions: 116.0 x 89.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

JEAN DUBUFFET

Chassé Croisé, 1961

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 81.0 x 100.0 cm

Dimensions: 81.0 x 100.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Sammlung Beyeler

© ProLitteris, Zürich / Foto: Robert Bayer

PHYSIOGNOMIC

ILLEGIBILITY

JEAN

DUBUFFET’S POSTWAR PORTRAITS BY KENT MITCHELL MINTURN

From

the summer of 1946 to the fall of 1947, Jean Dubuffet produced a series of

comical, irreverent portraits depicting some of the most important literary

figures of his day, including Antonin Artaud, Joë Bousquet, Marcel Jouhandeau,

Henri Michaux, Jean Paulhan, Francis Ponge, and Jules Supervielle. While many

of these individuals are not widely known by AngloAmerican readers, at the time

they constituted—to borrow the title of Gaëtan Picon’s canonical postwar

study—a veritable Panorama of New French Literature.1 Some were former

Résistant figures being lauded as heros, while others were coming under fire in

the postwar period for having contributed to German publications during the

Occupation. Jean-Paul Sartre, for reasons that will become clear, represents

perhaps the most conspicuous absence from Dubuffet’s panthéon. In October of

1947, Dubuffet exhibited his portraits in Paris at the Galerie René Drouin

under the sardonic title, Les gens sont bien plus beaux qu’ils croient: vive

leur vraie figure [People Are Much More Beautiful Than They Think: Long Live

Their True Face].2

According

to most accounts, Dubuffet’s foray into the genre of portraiture was the direct

result of the elaborate weekly lunches he attended, along with an array of

other artists and literati, at the home of the wealthy American expatriate and

patron of the arts, Florence Gould. Dubuffet himself seems to be the source of

this oft-repeated origin story. In a letter to Gould dated August 4, 1946, he

confesses, “What an adventure you have thrown me into! Nothing was farther from

my thoughts than doing portraits! Now it’s all I think about . . . and it’s all

your handiwork . . .”3 In hindsight, however, Dubuffet’s statement to Gould rings

hollow for two reasons. First, because portraiture was on the artist’s mind

long before he began attending Gould’s lunches. Several academic and highly

naturalistic portraits from Dubuffet’s prewar (or “pre-history,” as he

preferred to call it) period still exist—e.g., one of his father, Georges

Dubuffet, 1919, another of his maternal Grandmother, 1919, and one of his

lifelong friend, the surrealist novelist Georges Limbour, 1920 [Fig. 18].

During the thirties, Dubuffet coupled his interest in portraiture with his

passion for theater and created life-sized paper maché portrait-masks of his

friends René Ponthier (a local musician), André Claude (the manager of

Dubuffet’s wine business), and Robert Polguère (an antique dealer), 1935 [Fig.

19], as well as whimsical puppets and portraits of his wife, Lili Carlu. And

secondly, because in his statement to Gould cited above, Dubuffet fails to

admit that his postwar portraits are closely related to the large number of

anonymous figures and “personnages” he painted during the Occupation and in the

months immediately following the Liberation, many of which were displayed at

Mirobolus, Macadam, et Cie., his second solo show at the Galerie René Drouin in

May of 1946. These earlier figures demonstrate Dubuffet’s interwar and

immediate postwar interest in what might be called the illegible, immensurable,

or de-standardized body—in short, the body that resists classicizing

anthropomorphism, anthropocentrism, and anthropometry.

THE

ILLEGIBLE, IMMENSURABLE, DE-STANDARDIZED BODY

Dubuffet’s

rejection of the legible, standardized body is readily apparent in several

paintings he finished just before he embarked on his Portraits series,

including: Volonté de puissance [Will to Power], 1946 [plate 9], and Archétypes

[Archetypes], 1945 [Fig. 20]. In my estimation these heavily impastoed “haute

pâte” [thick paste] works, which introduce base materials (e.g., sand, asphalt,

and pebbles) into high art, are not simply attempts to shock, or to achieve

succès de scandale, by returning figuration to a more “primitive” or infantile

state (as many of Dubuffet’s early critics and detractors claimed). They also

reflect, albeit negatively, an historically specific phenomena—namely, the

classicizing “rappel à l’ordre” and nationalistic “retour à la terre”

mentalities rampant in France at the time.4 Dubuffet’s writings from this

period are replete with explicit and implicit denunciations of this return to

classicism via the Renaissance. For instance in “Causette” [“Little Chat”], the

text that he wrote to accompany his portrait show, Dubuffet lambastes this

return of “Greekeries, post-Greekeries, and neo-Greekeries” in contemporary

art, and elsewhere describes himself as staunchly “anti-Humanist.”5

These

sentiments are expressed visually in Dubuffet’s Volonté de puissance [Will to

Power], a painting from the Mirobolus, Macadam, et Cie. series, which not

incidently takes its title from the Nietzschean phrase appropriated by the

Third Reich. When juxtaposed with one of Nazi artist Arno Breker’s sculptures,

Der Sieger [The Victor], 1939 [Fig. 21], which exemplifies the neo-classical

body officially sanctioned by the Third Reich, and by extension Vichy, during

the war, the target of Dubuffet’s attack becomes clear. The figure’s rough,

hirsute body is the polar opposite of the polished, intact body depicted by

Breker. In place of wholeness and perfection, Dubuffet presents us with a

grotesquely flattened, disproportionate, and incomplete figure. It is difficult

to discern if he is missing arms, or if they have been tied behind his back.

Between the figure’s squat legs genitals dangle unceremoniously, like a cow’s

udder.

Macadam

connotes the idea of the horizontal vector of the ground, or, more precisely,

an asphalt road, which is normally seen from above. Here that ground has

been raised to a fronto-parallel viewing position. Dubuffet’s “return to the

soil” is diametrically opposed to the Nazis’; it no longer takes the form of a

glorified sublimated Teutonic body rooted in the soil of the German Motherland—or

the French, Vichy equivalent, an autochthonous Greco-Roman Mediterranean body.

Rather, Dubuffet’s return to the soil is nothing more than, as he put it at the

time, “a rehabilitation of mud” for its own sake.6 Mud, soil, and sand are

non-precious substances materially speaking, but also semantically; in

Dubuffet’s hands they prevent his figures from taking on any higher symbolic

value. Further, the opacity of these base materials block both visual

penetration and interpretation, and undermine the observer’s attempts to read

anything “into” the figures. At the same time, when viewing this painting, it

is nearly impossible to miss the accidental “face” formed by the hair on the

figure’s chest and abdomen. By including this detail, Dubuffet emphasizes the fact

that faces are arbitrary, rather than transparent entrees into a figure’s true

inner character. As is evinced by his later objet trouvé driftwood sculpture,

Le vieux de la plage [The Old Man of the Beach], 1959 [plate 51], accidental

faces continued to intrigue the artist throughout his career.

Dubuffet’s

interwar and immediate postwar figures resist those classical Vitruvian ideals,

passed down through the Renaissance and resuscitated in France after World War

II, which seek to describe the human body as a perfectly proportioned,

measurable, and quantifiable constant. In many ways, Dubuffet’s figures are the

opposite of architect Le Corbusier’s contemporaneous neo-classicizing Plan of

the Modulor, 1945 [Fig. 22], based on the time-honored Golden Section ratio of

1:1.618. Somewhat surprisingly, Dubuffet and the architect were friends at the

time; the former gave the latter Danseuse de corde [Jump Roper], 1943 [plate

1], as a gift shortly after he painted it.7 Dubuffet’s Archetypes nullify Le

Corbusier’s “gold standard” of proportion and undermine the notion of the human

figure as an ideal form or universally recognized sign. The viewer cannot help

but ask: Of what are these figures archetypes? For what archetypical ideal do

they stand? And, if they are generalized archetypes, why do they contain

obvious particularities, such as the wrinkles around both figures’ eyes? This

oscillation between the general and the particular will be a defining strategy

of Dubuffet’s postwar portraits. Indeed, Dubuffet once admitted to Max Loreau,

the scholar in charge of editing the artist’s multi-volume catalogue raisonné,

that Archetypes was a direct predecessor to his Portraits series:

‘ ‘The

word archetype evokes for me something like a simplistic generic prototype

where any individual particularity is omitted. It should be noted that the

first painting of my series Mirobolus, Macadam et Cie., done in 1945, carries

the title Archetypes . . . This character of depersonalization is certainly a

constant of all my personages . . .The charm of my Portraits enterprise

consisted exactly in undergoing a treatment of depersonalization of the

effigies of the persons designated. This persistent drive to

depersonalize the persons seems to me to precede the paintings (and is

more or less conscious in my mind throughout their execution).8 ‘’

Dubuffet

was quick to add that his technique of depersonalization requires “imagination

from the viewer to recognize and complete the portrait.”9

PHYSIOGNOMIC

ILLEGIBILITY

“These

pleasantries signify nothing.”10 —CRITIC MICHEL ARVILLE, 1947

Dubuffet’s

postwar portraits, or “anti-portraits” as he preferred to call them, similarly

resist typification, standardization, and legibility. His goal, he explicitly

declared in 1947, was to “block any likeness,” and to “multiply the obstacles”

between the viewer and the portrayed individual, in hopes that his effigies

would remain “open to multiple interpretations.” “Those who have spoken about

my Portraits as an endeavor of psychological penetration,” he claimed,

“have understood nothing.”11

Given

Dubuffet’s stated goals, the crisis in legibility that accompanied his

Portraits show at the Galerie René Drouin comes at no surprise. Contemporary

critics were completely baffled, especially when discussing the role of mimesis

in Dubuffet’s series. Their reactions range from one end of the spectrum to the

other. Whereas one critic, René Guilly, felt Dubuffet’s portraits “resembled

the living individuals too much,” another declared that the paintings

“absolutely do not evoke the person represented.”12 Dubuffet’s sitters

similarly had mixed reactions. Francis Ponge, for example, was pleasantly

amused with his likeness, Francis Ponge, jubilation [Francis Ponge,

Jubilation], 1947 [Fig. 23], while Paul Léautaud, on the other hand, became so

enraged upon seeing his effigy he attempted to destroy it with the end of his

cane.13

Yet, if

we look at the critical reception as a whole there is one word that perennially

resurfaces in the writings of detractors and supporters alike: “physiognomy.”14

Commonly understood, physiognomy refers to the art or pseudo-science of

determining an individual’s temperament or character from his or her outward

facial features. It presupposes that the face is a text or code which can be

read or deciphered; as such, physiognomy can be thought of as a kind of applied

semiotics of the body. Although the idea of physiognomy dates to antiquity, it

was not systematized and codified until the publication of Giovanni Battista

Della Porta’s Della Fisionomia dell’Uomo in 1586; in the following centuries,

Della Porta’s work was refined and augmented, most notably, by Charles Le Brun

and Johann Caspar Lavater.15

While

it might be argued that there is nothing inherently remarkable about the word

“physiognomy” resurfacing in the critical literature surrounding Dubuffet’s

show—it is, after all, a term inextricably intertwined with the genre—we should

not lose sight of how loaded the word had become at this specific historical

moment in postwar Europe. In the second half of the 19th century, thanks to the

photographic travails of Alphonse Bertillon, Duchenne de Boulogne, and Francis

Galton among others, physiognomy was elevated to the status of a positivist

epistemology.16 And as the all-too-familiar story goes, 50 years later the

Nazis hijacked the idea of “scientific” physiognomy, combined it with dubious

notions about race and eugenics, or inherited characteristics, and used it for

their own reprehensible ends.17 Dubuffet’s rejection of physiognomy at this

particular moment, then, should not be taken lightly, nor should it be treated

as an isolated case. It is part of a wider phenomenon in postwar European

painting that extends beyond the scope of this essay. Indeed, a more complete

analysis of this issue would include a further consideration of postwar

portraits by Francis Bacon and Alberto Giacometti, and those by Dubuffet’s

friends, Jean Fautrier, Tal Coat, Henri Michaux, and Antonin Artaud, as well as

an investigation into the profound role the human face played in postwar

philosophical, literary, ethical, and cultural debates.18

BLOCKING

LIKENESS

In his

postwar Portraits, Dubuffet creates obstacles between the material signifier of

the painting and the signified sitter in three main ways. First and foremost,

Dubuffet blocks likeness by purposefully emphazing the materiality and opacity

of his painted surfaces. Physiognomic opacification in portaiture and the

deconstruction of the genre’s monopoly on mimesis and verisimilitude via this

strategy is nothing new in the history of modern art, in fact it very well may

be an essential facet of it—we need look no further than Paul Cézanne’s

portraits of his wife Mary-Hortense Fiquet, or Pablo Picasso’s 1906 Portrait of

Gertrude Stein. Yet, Dubuffet clearly takes things much further with his

heavily impastoed, monochromatic “pâte.” This “paste,” “dough,” or “pasta,” (as

it can be alternately translated) acts like a culinary substance which engages

senses other than the visual; the viewer must “devour” these paintings corporally,

rather than look at them from a cerebrally-detached distance. Dubuffet

encourages associations of this sort when, in the subtitle to his show, he

describes his Portraits as “cuite et confite dans la mémoire” or “cooked and

preserved in memory.” “Confite,” suggests conservation, but also something

gelatinous, and non-transparent. Likewise, culinary metaphors pepper the

artist’s introductory essay for the show. Critics, in turn, were inspired to

use similar metaphors when commenting on his portraits.19

The

French word for “material,” matière, can mean either the physical substance one

would use to build something, or the “contents” or “subject matter” (as in the

phrase Table des matières, a “Table of Contents”). At the formal level,

Dubuffet conflates these two ideas so that the materiality of the paint

confounds our attempts to look into the “contents” or “substance” of the

depicted individual. To the same ends, through his painterly process Dubuffet

combines the two meanings of the French word trait, which connotes both a mark,

such as a brushstroke or a drawn line, and a feature of someone’s personality

(in the same sense that the word is used in English to refer to a personality

“trait”). In Dubuffet’s portraits the incised trait remains at one with the thick

surface of the canvas, it no longer relates to any imagined internal

characteristic.20

Second,

as in his earlier Archetypes, Dubuffet oscillates back and forth between the

general and the particular.21 He includes the “accidental” and “insignificant”

in order to cancel out any trait “others might quite rightly have judged more

significant.”22 In each case Dubuffet begins with a very rudimentary plan, and

then adds just enough information to suggest the individual identity of the

sitter. For example, in Antonin Artaud aux houppes [Antonin Artaud with Tufts

of Hair], 1947 [Fig. 24], he adds the actor’s recognizable wild tufts of hair

and a careful line tracing his emaciated jawline, ruined by the electroshock

therapy he received in a psychiatric hospital in Rodez during the war. This

oscillation between general and particular prevents Dubuffet’s portraits from

becoming “caricatures” or theatrical “masks” that aim to fix a face in time. As

Benjamin Buchloh has observed, “ . . . both caricature and mask conceive of a

person’s physiognomy as fixed rather than a fluid field: in singling out

particular traits, they reduce the infinity of differentiated facial

expressions to a metonymic set.”23

Lastly,

in his portraits Dubuffet blocks likeness through a lively game of nominalism.

The artist often claimed that the act of titling a work was itself an essential

part of the artistic process, and once praised critic Renato Barilli for

rightly stressing the nominaliste side of his overall enterprise.24 As Norman

Bryson has argued, the practice of physiognomy traditionally relies on certain

“syllogisms” which seek to embed it within common language and “naturalize”

otherwise tenuous connections, as can be seen in the “Similarities Between the

Head of an Ox and a Man” illustration included in Charles Le Brun’s Conférence

sur l’expression générale et particulière, 1688 [Fig. 25].25 This kind of logic

was unfortunately alive and well in France in the postwar period [Fig. 26]. In

Dubuffet’s praxis, Michaux becomes a spider, René Bertele a wild cat, and

Georges Limbour is equated to a crustacean or chicken droppings [plate 11].

However, in contrast to the example from Le Brun’s book, or the more recent

page from a widely-read Parisian newspaper, Dubuffet’s animal-human connections

are obviously contrived and over the top, and accordingly, strike the viewer as

strange, unnatural, and even preposterous. He uses this effect of estrangement

to emphasize the schism that exists between the painted portrait and the actual

person.26 In the same manner, Dubuffet’s creative titling disrupts the genre of

portraiture’s long-standing promise of illuminating a connection between the

sitter’s image and his or her class, vocation, or ethnicity. For example, at

one point, he nominates Paul Léautaud the “Général d’Empire” even though

everyone knew he was, in fact, a writer. Georges Limbour becomes a “Mexican”

king, Edith Boissonnas a “Tibetan” demon, Henri Michaux a “Japanese” actor, and

Léautaud an “Indian” sorcerer, when, once again, audiences knew they were not

Mexican, Tibetan, Japanese, or Native American, respectively. This

enthnographic confusion was purposefully compounded by Dubuffet’s choice to

also exhibit six “L’Arbi” paintings, done in early 1947 during his first of

three trips to the Sahara, along with his portraits.27

You may

read whole essay from New York University web page writing by Kent Mitchell

Minturn to click above link.

WILHELM SASNAL

Anka, 2012

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 40.0 x 35.0 cm

Dimensions: 40.0 x 35.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

© Wilhelm Sasnal / Foto: Robert Bayer

WILHELM SASNAL

Kacper, 2012

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 40.0 x 35.0 cm

Dimensions: 40.0 x 35.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

© Wilhelm Sasnal / Foto: Robert Bayer

WILHELM SASNAL

Partisans, 2005

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 40.0 x 50.0 cm

Dimensions: 40.0 x 50.0 cm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

© Wilhelm Sasnal / Foto: Robert Bayer

GERHARD RICHTER: REAL & TANGIBLE ACCOMPLISHMENTS

AS A YOUNG MAN

While the years immediately following the end of World

War II were in many ways difficult, Richter also has fond memories of this

time, not least because he found he had access to books that had previously

been forbidden under Nazi control. Speaking to Robert Storr, Richter explained:

"It was very nasty, [but] when the Russians came to our village and

expropriated the houses of the rich who had already left or were driven out,

they made libraries for the people out of these houses. And that was fantastic."1 In

a later conversation with Jan Thorn-Prikker, Richter elaborated, "Cesare

Lombroso's Genius and Madness, Hesse, Stefan Zweig, Feuchtwanger, all that

middle-class literature. It was a wonderful, care-free time … made it easy to

forget the dark side of things."2 Dietmar Elger, having described Richter's mother

Hildegard's role in encouraging her son's interest in Nietzsche, Goethe,

Schiller and others, notes that it was an "endless supply of illustrated

books that prompted his own first drawings."3 In

an interview with Jeanne Anne Nugent, Richter recalls studying art "from

books and from the little folios with art prints that you used to get then – I

remember Diego Velázquez, Albrecht Dürer, Lovis Corinth […] It was simply a

matter of what was around, what we saw and bought for ourselves."4

It was around this time, at the age of 15 or 16, that

Gerhard's passion for art began in earnest, having an early epiphany during an

eight-week summer camp organized by the Russian-controlled State, where

"for the first time he spent a lot of time drawing."5 One

of the first drawings that Richter recalls and acknowledges producing6 as

a young man in 1946 was a nude figure copied from a book, which his parents are

said to have reacted to with both pride and embarrassment.7 He

recalls also having made landscapes and self-portraits, and perhaps more

unusually, often working in watercolours. In a 2002 interview with Storr, Richter

describes a watercolour drawing he produced whilst living in the village of

Waltersdorf of a group of people dancing. "Automatically I was an

outsider. I couldn't speak the dialect and so on. I was at a club, watching the

others dance, and I was jealous and bitter and annoyed. So in the watercolor,

all this anger is included, at 16. It was the same with the poems I was writing

– very romantic, but bitter and nihilistic, like Nietzsche and Hermann

Hesse."8

In 1947, while still studying stenography, accounting and Russian at college in nearby Zittau, Richter began attending evening classes in painting. Little has been documented about these first painting lessons, although Elger records that before completing the course, Richter realized that he had learnt all that he was likely to from the teachers there.9 A year later, Richter moved into a hostel for apprentices in Zittau, leaving his family home in Waltersdorf.

While clearly passionate about art, on completing his studies in Zittau in 1948, Richter did not assume his career would be as a painter, and for a while considered an eclectic array of professions, including forestry, dentistry and lithography. Looking for openings that would use his artistic skills for trade and commercial purposes if not in the fine art arena, his first position was as a member of a team producing banners for the German Democratic Republic government. Storr recounts that during his five months in this post, Richter never had the opportunity to actually paint any of the banners himself, instead being charged with the task of taking the old banners and cleaning them up ready for his colleagues to paint.10 In February 1950 he was taken on as an assistant set painter for the municipal theatre in Zittau. Richter had recently been involved with an amateur theatre group11, so it was perhaps through this, or even, as Storr proposes, through friends from his evening classes, that he was aware of and disposed to the role at the theatre. During his few months here, Elger notes that he enjoyed working on the sets for productions including Goethe's Faust and Schiller's William Tell among others. His career in the theatre came to an abrupt end, however, when the young Richter refused to do wall painting work on the theatre's staircases, and was promptly dismissed.12