FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: UNPACKING THE ARCHIVE AT MOMA NEW YORK

June 12, 2017 – October 1, 2017

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT:

UNPACKING THE ARCHIVE AT MOMA NEW YORK

June 12, 2017 – October

1, 2017

Major retrospective of

Frank Lloyd Wright delves into archives to present fresh perspectives on the

renowned architect’s practice.

Exhibition Presents

Nearly 400 Objects from the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives in New York to Mark the

150th Anniversary of Wright’s Birth

The Museum of Modern Art

presents a major exhibition that critically engages the multifaceted practice

of Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867– 1959), one of the most prolific and

renowned architects of the 20th century. A radical designer and intellectual,

Wright embraced new technologies and materials, pioneered do-it yourself

construction systems and avant-garde experimentation, and advanced original

theories with regards to nature, urban planning, and social politics. Marking

the 150th anniversary of the American architect’s birth on June 8, 1867, the

exhibition comprises nearly 400 works made from the 1890s through the 1950s,

including architectural drawings, models, building fragments, films, television

broadcasts, print media, furniture, tableware, textiles, paintings,

photographs, and scrapbooks, along with a number of works that have rarely or

never been publicly exhibited. Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive

is presented by MoMA in collaboration with the Avery Architectural & Fine

Arts Library, Columbia University, New York, and organized by Barry Bergdoll,

Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art, and

the Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia

University; with Jennifer Gray, Project Research Assistant, Department of

Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art.

In a career spanning

seven decades, Wright designed more than 1,000 buildings and realized over 500.

Ever concerned with posterity, Wright preserved most of his drawings—despite

some tragic losses to fires—to form an archive that he hoped would perpetuate

his architectural philosophy, first as a tool in the production of architecture

in the Taliesin Fellowship, an apprenticeship program he founded in the 1930s

at his studio-residences in Wisconsin and Arizona, and subsequently as an

academic resource for outside researchers. Progressively catalogued and opened

to specialists by The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, the archive was jointly

acquired by The Museum of Modern Art and Avery Architectural & Fine

Arts Library at Columbia

University in 2012. This exhibition celebrates this pioneering collaboration

and the new accessibility of the collection to both scholars and the

public.

Unpacking the Archive

refers to the monumental task of moving 55,000 drawings, 300,000 sheets of

correspondence, 125,000 photographs, and 2,700 manuscripts, as well as models,

films, building fragments, and other materials. It also refers to the work of

interpretation and the close examination of projects that in some cases have

received little attention. For this exhibition, a group of scholars and a

museum conservator were invited to “unpack”— contextualize, ask questions

about, and otherwise explore—an object or cluster of objects of their choosing.

Their processes of discovery are recorded in a series of short films that

introduce the thematic sections of the exhibition. The questions posed

illuminate the complex historical periods through which Wright lived, from the

late 19th century, marked by optimism, through the Great Depression of the

1930s, to the decades following World War II, when the United States experienced

great demographic and economic growth. Each scholarly inquiry offers insights

at once historical and contemporary in resonance, touching on issues that

include landscape and environmental concerns, the relationship of industry to

daily life, questions of race, class, and social democracy, and the expanding

power of mass media in forming reputations and

opinions.

Frank Lloyd Wright at 150

is organized around a central chronological spine highlighting many of Wright’s

major projects, which will be illustrated with some of his finest drawings and

include key works such as Unity Temple (1905–08), Fallingwater (1934–37), the

Johnson Wax Administration Building (1936–39), and the Marin County Civic

Center (1957–70). Unfolding from this orienting spine are 12 subsections,

covering themes both familiar and little explored, that highlight for visitors

the process of discovery undertaken by invited scholars, historians,

architects, and art conservators.

REFRAMING THE IMPERIAL

HOTEL

KEN OSHIMA ( UNIVERSITY

OF WASHINGTON )

The Imperial Hotel in

Tokyo (1913–23) was one of Wright’s most ambitious projects, a monumental

building with Western services, Japanese protocol for Imperial visits, and

integrated gardens, which famously survived the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

The central object in this section is Wright’s personal copy of a very rare

illustrated book on the Imperial Hotel building published shortly after its

completion, which Wright annotated with sketches and visual enhancements. It is

an unparalleled opportunity to see this now demolished masterpiece as it

originally stood. It is displayed alongside a dozen of the nearly 1,100

drawings of the Imperial Hotel that exist in the archive, as well as original

furniture, textiles, and tableware from the hotel, which together demonstrate

the attention Wright paid to every detail of the hotel design in an attempt to

make an integrated work of art.

ORNAMENT

SPYROS PAPAPETROS

(PRINCETON UNIVERSITY)

Famously, modernist

architects advocated the elimination of decoration from buildings, yet

ornamentation persists throughout Wright’s design work in a great variety of

forms. Beginning with Midway Gardens (1913–14), an elaborately decorated

entertainment complex in Chicago, this section traces the transformation of

ornament across decorative artifacts and architectural relics, including a

copper urn, textiles, mosaics, murals, stained glass doors, and concrete

blocks. Wright envisioned these fragments as parts of an integrated whole, as

demonstrated in projects such as the V.C. Morris Store in San Francisco

(1948–49) and the Greek Orthodox Church in Milwaukee (1955–61). He also

experimented with commercial designs, including a line of glassware for the

Dutch firm Leerdam Glasfabriek, covers for Liberty magazine, and a “Taliesin

Line” of fabrics for F. Schumacher and Co.

ECOLOGIES &

LANDSCAPES

THERESE O’MALLEY

(NATIONAL GALLERY, WASHINGTON, DC) &

JENNIFER GRAY (MOMA)

From his early

celebration of the prairie landscapes of the Midwest to his experiments with

living in harmony with the Sonoran desert of the Southwest, Wright explored the

most varied terrains and ecosystems. Two rarely studied drawings in the

exhibition offer new insights. A planting plan, called the “Floricycle,” for

the Darwin Martin House in Buffalo, New York (1903–06), reveals a surprising

mixture of native and exotic plants, raising questions about Wright’s

dedication to regional landscapes and indigenous plants. While an undated

graphic design for the Friends of Our Native Landscape, an environmentalist

group founded by prominent landscape designer Jens Jensen, invites reflection

on Wright’s views on the conservation versus transformation of sites. Following

from these provocations is a selection of projects in which Wright attempts to

integrate architecture and the natural world, including an estate for Sherman

Booth that negotiated deep ravines and escarpments, and his monumental project

for San Marcos-in-the-Desert, represented in the exhibition with presentation

drawings and a large-scale watercolor depicting the complex from the air.

LITTLE FARMS UNIT

JULIET KINCHIN (MoMA)

A little-known model of

an experimental farm that Wright designed in 1932–33 reveals how the architect

utilized back-to-the-land strategies during the Great Depression, with the goal

of allowing people to lead independent, productive lives and derive

sustenance—both physical and spiritual—from nature. Photographs, cropping

plans, and drawings demonstrate that these “Little Farms” were part of an

ambitious farm-to-market system. Poster designs and films complement these

materials and draw connections between Wright’s ambitions and New Deal programs

initiated by President Roosevelt, as well as Soviet programs for

industrializing agricultural production.

Nakoma Country Club Elizabeth

Hawley (CUNY Graduate Center) Wright was keenly interested in American Indian

culture, especially in the opening decades of the 20th century, when native

culture was widely celebrated as an authentic expression of American identity.

This section centers on an unrealized project for the Nakoma Country Club near

Madison, Wisconsin (1923), in which Wright appropriated native architectural

forms, such as wigwams and tipis, and also designed figurative sculptures

depicting American Indians. Archival photographs reveal that he collected

native artifacts and even designed and built a totem pole, now lost, at

Taliesin West, his residence and studio in Arizona. Together, the projects

demonstrate how Wright’s interest in American Indian imagery existed in tension

with prevailing racial stereotypes and imperialist strategies.

ROSENWALD SCHOOL

MABEL WILSON (COLUMBIA

UNIVERSITY)

While Wright explored the

relationship between learning and educational spaces throughout his career,

this section of the exhibition explores a little-known design Wright drew up in

1928 for the Rosenwald Foundation, for a model school building for African

American children. Created by Julius Rosenwald, a co-owner of Sears, Roebuck

& Company in Chicago, the Rosenwald Foundation’s focus on arts and

education among African Americans included an ambitious project to subsidize

the construction of rural schools throughout the South. Wright’s design

reoriented this program of schools for the segregated South from traditional

clapboard schoolhouses to innovative buildings that the students were intended

to help build, making hands-on labor an integral part of education. The

project, begun in 1928, never progressed beyond the schematic stage.

DRAWING IN THE STUDIO

JANET PARKS (AVERY

DRAWINGS & ARCHIVES, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY)

Wright’s architectural

drawings, some of the most renowned of the 20th century, are remarkable for

their artistic quality and signature style. Yet most of them were produced by

the ever-changing cast of draftsmen, students, and apprentices working in his

studios, many of whom left their own imprint on Wright’s legacy. This section

analyzes Wright’s drawings for clues to how his practice operated, the

personalities involved, and the processes and materials employed at various times.

Before Wright established

an independent practice, early work shows him drawing in the style of his

mentor, Louis Sullivan. The Japanese-inspired compositions of Marion Mahony,

one of the first licensed female architects in the US and Wright’s most talented

renderer in the Oak Park studio, is seen in a rare drawing that bears her

signature.

READING ‘’MILE- HILE’’

BARRY BERGDOLL (MoMA

& COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY)

Wright’s proposal for a

mile-high skyscraper—for which there was neither commission nor

client—commanded headlines when he released his design in a press conference at

Chicago’s Sherman Hotel on October 16, 1956. Despite his unprecedented

ambitions—even today, the tallest building in the world, in Dubai, is only a

half-mile high—Wright’s “mile-high” proposal has never occupied a large place

in architectural history. Nor has the possible meaning of the inscriptions that

occupy the upper half of one of Wright’s super-tall drawings of the project

been “unpacked.” This drawing is shown in the exhibition alongside archival

photographs, brochures, letters, and telegrams documenting the 1956 press

conference and the public’s reaction to it.

The proposed tower culminated

in seven stories of television studios, even as Wright was himself becoming

something of a TV personality, first as a mystery guest on the What’s My Line?

game show (June 3, 1956) and then as a guest on The Mike Wallace Interview

(September 1 and 2,

1957). Clips from these appearances are included in the galleries. This section

explores how Wright was aiming for a place in the new media of publicity, and a

place in history.

URBANISM

NEIL LEVINE (HARVARD

UNIVERSITY)

This section is anchored

by Wright’s Skyscraper Regulation project for a nine-block area of downtown

Chicago (1926), which reveals the broad reach of his ideas about the city and

serves as a window into his career-long efforts in urban design. Intended to

relieve the congestion caused by unchecked skyscraper development and by

massive increases in vehicular traffic, the city grid is opened up to create

internal courtyards with underground parking, while raised sidewalks separate

pedestrians from cars and trucks. Between 1896 and 1913, Wright conceived

a radically new method of subdivision allowing groupings of houses to preserve

an unprecedented degree of privacy while creating a sense of community. In the

final decades of his career, he turned to the design of civic centers, cultural

centers, and mixed-use development that revitalized the heart of the city in an

era dominated by the automobile and suburb. The exhibition includes several of

these large projects, often megastructures incorporating roadways and parking,

designed for Madison, Pittsburgh, Washington, DC, and Baghdad.

BUILDINGS SYSTEMS

MATTHEW SKJONSBERG (SWISS

FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY) &

MICHAEL OSMAN (UNIVERSITY

OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES)

Though Wright’s name is

often equated with spectacularly singular residential designs, this section

examines his engagement with industry in various ways to design lower-cost

houses that would be affordable to middle-class Americans. The American

System-Built Houses designed in 1915–17 utilized a wood-based system that

relied on factory-produced components, mail-order distribution techniques, and

licensed contractors to ensure an affordable, high-quality product. By the

early 1950s, Wright developed a do-it-yourself process called the Usonian

Automatic system that enabled individuals to build their own houses using

self-cast concrete blocks. The competing systems, which used entirely different

materials and modes of production, bracket decades in which Wright responded to

the shifting economic and labor conditions of the Depression and postwar

periods by alternatively embracing mass production and handicraft to advance

both his architectural brand and his democratic vision.

CIRCULAR GEOMETRIES

MICHAEL DESMOND

(LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY)

Wright was continually in

search of systems of design that could both control all elements of structure

and space harmonically and serve as a generator of form. From the 1930s, he

moved from orthogonal grids of angular forms to more dynamic organizational

systems based on circles and arcs to engage and shape perceptions of the

landscape. Starting from the unusual approach of laying out a suburban division

of land for residential development with a series of tangent circles in a

project for Galesburg, Michigan (1946–49), this section traces the evolution of

the architect’s circular planning. These experiments culminated in Wright’s

residential designs for Raúl Baillères, a circular house that engaged the broad

sweep of Acapulco Bay in Mexico, and V.C. Morris, a spiral structure clinging

to a precipice overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

NEW YORK MODELS

CONSERVED

ELLEN MOODY (MoMA)

Wright often used

meticulously detailed building models as publicity tools to persuade clients

and as props in staged photographs, and they were central to his organization

of museum exhibitions of his work. Made of light wood and cardboard painted in

bright colors, the models were easy to transport but inherently fragile. They

were frequently repaired and bear traces of their travels and travails. The

exhibition features two newly restored models for projects for Manhattan: St.

Mark’s Tower (1927–29) and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1943– 59). MoMA

conservator Ellen Moody conducted extensive archival research and closely

investigated the models’ physical fabric through discussions with experts and

curatorial staff, X-rays, paint analysis, and the employment of various digital

technologies. These conservation processes are documented in videos in the

galleries, demonstrating the spectrum of approaches possible in contemporary conservation

practice and revealing new insights into the working methods of the architect

and his studio.

https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1660?locale=en

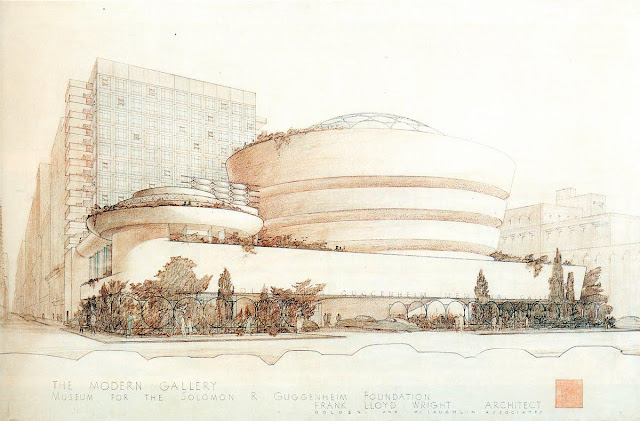

SOLOMON R.

GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, NEW YORK 1943–1959

Perspective

from Fifth Avenue

Ink, pencil,

and colored pencil on tracing paper

Dimensions:

65.7 × 101 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

NAKOMA COUNTRY CLUB

Wright was keenly

interested in American Indian art and architecture, especially in the early

decades of the twentieth century, when native culture was widely celebrated by

many people as an authentic expression of American identity, even as native

peoples were being colonized and displaced from their lands. In addition to

believing that indigenous imagery and designs could free American

architecture of the baggage of European historical models, Wright

was associated with several clubs and groups that incorporated native-inspired rituals

into their programs, and his circle included prominent supporters of American

Indian rights. In an unrealized project for the Nakoma Country Club

(1923–24), near Madison, Wisconsin, Wright appropriated native architectural

forms, such as wigwams and tipis, using them interchangeably despite the fact

that they belong to distinct indigenous cultures. The design demonstrates how,

like most of his contemporaries, Wright tended to romanticize and

generalize American Indian culture. The complex picture that emerges is one in

which Wright’s interest in American Indian imagery exists in tension with

prevailing racial stereotypes and imperialist strategies.

NAKOMA COUNTRY CLUB

IMPERIAL

HOTEL, TOKYO 1913–1923

IMPERIAL

HOTEL, TOKYO 1913–1923

STONE CARVING

AND POLYCHROME DECORATIONS FOR THE NORTH PARLOR

Gold Paint,

Pencil, and Colored Pencil on Tracing Paper

Dimensions:

55.6 × 91.1 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

REFRAMING THE IMPERIAL

HOTEL

The Imperial Hotel in

Tokyo took over a decade to build—its earliest designs date from 1913 and it

was completed in 1923—and exerted a profound influence on both

Wright’s designs and the architecture of a modernizing Japan. From

his first encounter with the Ho-o-den, a Japanese pavilion at the

1893 Chicago World’s Fair, Wright had been inspired by traditional Japanese art

and architecture. He began collecting Japanese woodblock prints during his

first visit to Japan in 1905, subsequently mounting exhibitions of

them and becoming an important dealer. Now he was called upon to

build a modern hotel adjacent to the Imperial Palace, at the very heart of the

Japanese capital—a monumental building with western services, Japanese protocol

for imperial visits, and integrated gardens. Alongside nearly 800

drawings of the project, the archive also contains Wright’s personal copy of

Teikoku Hoteru (Imperial Hotel), a very rare illustrated book on the

building published in 1923, shortly after its completion. The publication

allowed Wright, who had returned to the United States before the hotel opened,

not only to see the finished results of his work but to continue reworking,

adding notations, adjustments, and even landscaping details in pencil. The

photographs in the book, as well as others displayed here, frame the building

in highly aestheticized ways, while the building’s vertical windows create

meticulously controlled views of the garden and of Tokyo, not unlike the

compositions of the Japanese prints Wright admired. The architecture of the

Imperial Hotel together with its representation suggests the varied ways Wright

endeavored to engage and reframe cultural exchanges between East and West.

IMPERIAL HOTEL,

TOKYO 1913–1923

CROSS SECTION

LOOKING EAST

Ink, Pencil,

and Colored Pencil on Drafting Cloth

Dimensions:

38.1 × 101.6 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

JOHN STORRER

HOUSE

JOHN STORRER

HOUSE

UNITY TEMPLE, OAK PARK, ILLINOIS 1905-1908

UNITY TEMPLE,

OAK PARK, ILLINOIS 1905-1908

Perspective

Watercolor and Ink on Paper

30.5 × 63.8

cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

UNITY TEMPLE,

OAK PARK, ILLINOIS 1905-1908

THE MILE-HIGH

ILLINOIS, CHICAGO PROJECT 1956

PERSPECTIVE

WITH THE GOLDEN BEACON APARTMENT BUILDING PROJECT (1956–57)

Pencil,

Colored Pencil, and Gold Ink on Tracing Paper

Dimensions:

266.7 x 76.2 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

LUDWIG MIES

VAN DER ROHE (AMERICAN, BORN GERMANY 1886–1969)

FRIEDRICHSTRASSE

SKYSCRAPER PROJECT, BERLIN-MITTE, GERMANY 1921

Exterior

Perspective From North

Charcoal and

Graphite on Paper Mounted on Board

Dimensions:

173.4 x 121.9 cm

Mies van der

Rohe Archive, Gift of the Architect

THE MILE-HIGH

ILLINOIS, CHICAGO PROJECT 1956

ELEVATION AND

PLAN

Pencil and

Colored Pencil on Tracing Paper

Dimensions:

92.1 × 98.4 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

THE MILE-HIGH

ILLINOIS, CHICAGO PROJECT 1956

ENNIS HOUSE,

LOS ANGELES. 1924 – 1925

ENNIS HOUSE,

LOS ANGELES. 1924 - 1925

PERSPECTIVE

FROM THE SOUTHWEST

Pencil,

Colored Pencil and Ink on Tracing Paper

Dimensions:

51.1 x 99.4 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

ENNIS HOUSE,

LOS ANGELES. 1924 - 1925

V. C. MORRIS

GIFT SHOP, SAN FRANCISCO 1948–1949

V. C. MORRIS

GIFT SHOP, SAN FRANCISCO 1948–1949

SOUTH - NORTH

SECTION

Ink, Pencil,

and Colored Pencil on Tracing Paper

Dimensions:

74.9 × 88.9 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

V. C. MORRIS

GIFT SHOP, SAN FRANCISCO 1948–1949

MUSEUM OF

MODERN ART NEW YORK

MUSEUM

OF MODERN ART NEW YORK

Founded

in 1929 as an educational institution, The Museum of Modern Art is dedicated to

being the foremost museum of modern art in the world.

Through

the leadership of its Trustees and staff, The Museum of Modern Art manifests

this commitment by establishing, preserving, and documenting a collection of

the highest order that reflects the vitality, complexity and unfolding patterns

of modern and contemporary art; by presenting exhibitions and educational

programs of unparalleled significance; by sustaining a library, archives, and

conservation laboratory that are recognized as international centers of

research; and by supporting scholarship and publications of preeminent

intellectual merit.

Central

to The Museum of Modern Art’s mission is the encouragement of an ever-deeper

understanding and enjoyment of modern and contemporary art by the diverse

local, national, and international audiences that it serves. You may read more

about MoMA’s entire information to click below link.

http://press.moma.org/about/

MIDWAY GARDENS

MIDWAY GARDENS

FALLINGWATER

(KAUFMANN HOUSE), MILL RUN, PENNSYLVANIA 1934–1937

PERSPECTIVE

FROM THE SOUTHWEST

Pencil and

Colored Pencil on Paper

39.1 × 69.2

cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

ST. MARK’S

TOWER, NEW YORK PROJECT 1927 - 1929

Model Painted

Wood and Cardboard

Dimensions:

134.6 x 40.6 x 40.6 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

ST. MARK’S

TOWER, NEW YORK PROJECT 1927 - 1929

Plans,

Section, and Cutaway Perspective

Ink, Pencil,

and Colored Pencil on Cloth

Dimensions:

118.1 × 90.2 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

ST. MARK’S

TOWER, NEW YORK PROJECT 1927 - 1929

DARWIN D.

MARTIN HOUSE, BUFFALO, NEW YORK 1903 - 1906

FLORICYCLE

Ink on

Drafting Cloth

Dimensions:

81.6 × 101 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

DARWIN D.

MARTIN HOUSE, BUFFALO, NEW YORK 1903 - 1906

JOHNSON WAX

ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, RACINE, WISCONSIN 1936–1939

JOHNSON WAX

ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, RACINE, WISCONSIN 1936–1939

AERIAL

PERSPECTIVE

Ink, Ink

Wash, Pencil, and Colored Pencil on Paper

Dimensions:

EST.: 48.3 × 97.5 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

JOHNSON WAX

ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, RACINE, WISCONSIN 1936–1939

"MARCH

BALLOONS" 1955 DRAWING BASED ON A C. 1926

DESIGN FOR

LIBERTY MAGAZINE

Colored

Pencil on Paper

Dimensions:

62.2 × 71.8 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York

AMERICAN

SYSTEM-BUILT (READY-CUT) HOUSES.

PROJECT, 1915

- 17. MODEL OPTIONS Lithographs

Dimensions:

Each: 27.9 x 21.6 cm

The Museum of

Modern Art, New York. Gifts of David Rockefeller, Jr,. Fund,

Ira Howard

Levy Fund and Jeffrey P. Klein Purchase Fund

SIDE CHAIR

FOR THE C. IMPERIAL HOTEL, TOKYO, C. 1922

Oak and

Caning

Dimensions:

95.9 × 40 × 43.8 cm

The

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of

Dr. and Mrs.

Roger G. Gerry, 1968

MADISON CIVIC

CENTER (MONONA TERRACE), MADISON,

WISCONSIN

PROJECT 1938–1959

Night

Perspective From the West, 1955

Ink and

Pencil on Paper Mounted on Plywood

Dimensions:

81.3 × 101.6 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

TALIESIN WEST

TALIESIN WEST

V. C. MORRIS

HOUSE, SAN FRANCISCO PROJECT 1944 – 1946

V. C. MORRIS

HOUSE, SAN FRANCISCO PROJECT 1944 - 1946

PERSPECTIVE

FROM BELOW

Ink, Pencil,

and Colored Pencil on Tracing Paper

Dimensions:

101.9 × 106.4 cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

GORDON STRONG

AUTOMOBILE OBJECTIVE & PLANETARIUM,

SUGARLOAF

MOUNTAIN, MARYLAND PROJECT 1924–1925

GORDON STRONG

AUTOMOBILE OBJECTIVE & PLANETARIUM,

SUGARLOAF

MOUNTAIN, MARYLAND PROJECT 1924–1925

Perspective

Pencil and Colored Pencil on Tracing Paper

50.2 × 78.1

cm

The Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |

Avery

Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

MARIN COUNTY

CIVIC CENTER

MARIN COUNTY

CIVIC CENTER

WAINWRIGHT

TOMB

WAINWRIGHT

TOMB

PALMER HOUSE

PALMER HOUSE

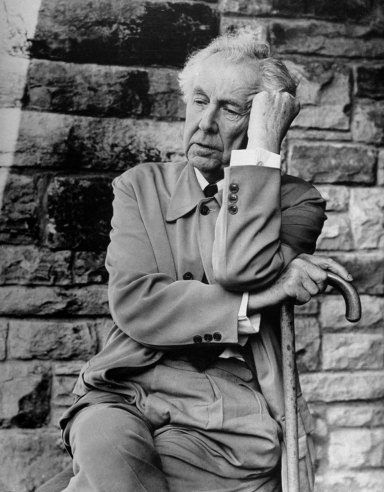

THE LIFE OF FRANK LLOYD

WRIGHT

EARLY LIFE

The experiences of

Wright’s upbringing were crucial in forming Wright’s unique aesthetic.

Frank Lloyd Wright was

born in Richland Center, Wisconsin, on June 8, 1867, the son of William Carey

Wright, a preacher and a musician, and Anna Lloyd Jones, a teacher whose large

Welsh family had settled the valley area near Spring Green, Wisconsin. His

early childhood was nomadic as his father traveled from one ministry position

to another in Rhode Island, Iowa, and Massachusetts, before settling in

Madison, Wis., in 1878.

Wright’s parents divorced

in 1885, making already challenging financial circumstances even more

challenging. To help support the family, 18-year-old Frank Lloyd Wright worked

for the dean of the University of Wisconsin’s department of engineering while

also studying at the university. But, he knew he wanted to be an architect. In

1887, he left Madison for Chicago, where he found work with two different firms

before being hired by the prestigious partnership of Adler and Sullivan,

working directly under Louis Sullivan for six years.

EARLY WORK

As Wright explored his

personal interests, his work ushered in brand new styles of design.

In 1889, at age 22,

Wright married Catherine Lee Tobin. Eager to build his own home, he negotiated

a five-year contract with Sullivan in exchange for the loan of the necessary

money. He purchased a wooded corner lot in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park and built

his first house, a modest residence reminiscent of the East Coast shingle style

with its prominent roof gable. It also reflected Wright’s ingenuity as he

experimented with geometric shapes and volumes in the studio and playroom he

later added for his ever-growing family of six children. Remembered by the

children as a lively household, filled with beautiful things Wright found it

hard to go without, it was not long before escalating expenses tempted him into

accepting independent residential commissions. Although he did these on his own

time, when Sullivan became aware of them in 1893, he charged Wright with breach

of contract. It is not clear whether Wright quit or was fired, but his

departure was acrimonious, creating a rift between the two men that was not

repaired for nearly two decades. The split, however, presented the opportunity

Wright needed to go out on his own. He opened an office and began his quest to

design homes that he believed would truly belong on the American prairie.

The William H. Winslow

House was Wright’s first independent commission. While conservative in

comparison to work of a few years later, with its broad sheltering roof and

simple elegance, it nonetheless attracted local attention. Determined to

create an indigenous American architecture, over the next sixteen years he set

the standards for what became known as the Prairie Style. These houses

reflected the long, low horizontal prairie on which they sat with low-pitched

roofs, deep overhangs, no attics or basements, and generally long rows of

casement windows that further emphasized the horizontal theme. Some

of Wright’s most important residential works of the time are the Darwin D.

Martin House in Buffalo, New York (1903), the Avery Coonley House in Riverside,

Illinois (1907), and the Frederick C. Robie House in Chicago (1908). Important

public commissions included the Larkin Company Administration Building in

Buffalo (1903, demolished 1950) and Unity Temple in Oak Park (1905).

Creatively exhausted and

emotionally restless, late in 1909 Wright left his family for an extended stay

in Europe with Mamah Borthwick (Cheney), a client with whom he had been in love

for several years. Wright hoped he could escape the weariness and discontent

that now governed both his professional and domestic life. During this European

hiatus Wright worked on two publications of his work, published by Ernst

Wasmuth, one of drawings known as the Wasmuth Portfolio, Ausgeführte

Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright and one of photographs, Ausgeführte

Bauten, both released in 1911. These publications brought

international recognition to his work and greatly influenced other architects.

The same year, Wright and Mamah returned to the States and, unwelcome in

Chicago social circles, began construction of Taliesin near Spring Green as

their home and refuge. There he also resumed his architectural practice

and over the next several years received two important public commissions: the

first in 1913 for an entertainment center called Midway Gardens in Chicago; the

second, in 1916, for the new Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan.

In August 1914, Wright’s

life with Mamah was tragically closed as she, her two children and four others

were killed in a brutal attack and fire, intentionally started by an angry

Taliesin domestic employee. Emotionally and spiritually devastated by the

tragedy, Wright was able to find solace only in work and he began to rebuild

Taliesin in Mamah’s memory. Once completed, he then effectively abandoned it

for nearly a decade as he pursued major work in Tokyo with the Imperial Hotel,

which was demolished 1968, and Los Angeles with the Hollyhock House and Olive

Hill for oil heiress Aline Barnsdall.

TALIESIN FELLOWSHIP

Wright sought to teach

others by having them become active in each aspect of his projects

The years between 1922

and 1934 were both architecturally creative and fiscally catastrophic. Wright

had established an office in Los Angeles, but following his return from Japan

in 1922 commissions were scarce, with the exception of the four textile block

houses of 1923–1924 (Millard, Storer, Freeman and Ennis). He soon abandoned the

West Coast and returned to Taliesin. While only a few projects went into

construction, this decade was one of great design innovation for Wright. Among

the unbuilt commissions were the National Life Insurance Building (Chicago,

1924), the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective (Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland,

1925), San Marcos-in-the-Desert resort (Chandler, Arizona, 1928), and St.

Mark’s-in-the-Bowerie apartment towers (New York City, 1928).

In 1928, Wright married

Olga Lazovich (known as Olgivanna), daughter of a Chief Justice of Montenegro,

whom he had met a few years earlier in Chicago. She proved to be the partner

and stabilizing influence he needed in order to refocus on “the cause of

architecture” he had begun decades earlier.

With few architectural

commissions coming his way, Wright turned to writing and lecturing which

introduced him to a larger national audience. Two important publications came

out in 1932: An Autobiography and The Disappearing

City. The first received widespread critical acclaim and would

continue to inspire generations of young architects. The second introduced

Wright’s scheme for Broadacre City, a utopian vision for decentralization that

moved the city into the country. Although it received little serious

consideration at the time, it would influence community development in

unforeseen ways in the decades to come. At about this same time, Wright and

Olgivanna founded an architectural school at Taliesin, the “Taliesin

Fellowship,” an apprenticeship program to provide a total learning environment,

integrating not only architecture and construction, but also farming,

gardening, and cooking, and the study of nature, music, art, and dance.

Wright’s apprenticeship

program lives on today through the Frank Lloyd Wright

School of Architecture.

LATER LIFE

For Wright, creation

continued until the very end

REMARKABLE RETURN

With this larger

community to take care of, and Wisconsin winters brutal, the winter of 1934

found the Wrights and the Fellowship in rented quarters in the warmer air of

Arizona where they worked on the Broadacre City model, which would debut in

Rockefeller Center in 1935. Wright was by this time still considered a great

architect, but one whose time had come and gone. In 1936, Wright proved this

sentiment wrong as he staged a remarkable comeback with several important

commissions including the S.C. Johnson and Son Company Administration Building

in Racine, Wisconsin; Fallingwater, the country house for Edgar Kaufmann in

rural Pennsylvania; and the Herbert Jacobs House (the first executed “Usonian”

house) in Madison.

At this same time, Wright

decided he wanted a more permanent winter residence in Arizona, and he acquired

some acreage of raw, rugged desert in the foothills of the McDowell Mountains

in Scottsdale. Here he and the Taliesin Fellowship began the construction

of Taliesin West as a winter camp, a bold new endeavor for desert living where

he tested design innovations, structural ideas, and building details that

responded to the dramatic desert setting. Wright and the fellowship established

migration patterns between Wisconsin and Arizona, which the Frank Lloyd Wright

School of Architecture continues to this day.

Acknowledging Wright’s

stunning reentry into the architectural spotlight, the Museum of Modern Art in

New York staged a comprehensive retrospective exhibition that opened in 1940. In

June 1943, undeterred by a world at war, Wright received a letter that

initiated the most important, and most challenging, commission of his late

career. Baroness Hilla von Rebay wrote asking him to design a building to house

the Solomon R. Guggenheim collection of non-objective paintings. Wright

responded enthusiastically, never anticipating the tremendous amount of time

and energy this project would consume before its completion sixteen years

later.

THE LAST DECADES

With the end of the war

in 1945, many apprentices returned and work again flowed into the studio.

Completed public projects over the next decade included the Research Tower for

the SC Johnson Company, a Unitarian meeting house in Madison, a skyscraper in Oklahoma,

and several buildings for Florida Southern College. Other, ultimately unbuilt,

projects included a hotel for Dallas, Texas, two large civic commissions for

Pittsburgh, a sports club for Hollywood, a mile-high tower for Chicago, a

department store for Ahmedabad, India, and a plan for Greater Baghdad.

Wright

opened his last decade with work on a large exhibition, Frank Lloyd

Wright: Sixty Years of Living Architecture, which was soon on an

international tour traveling to Florence, Paris, Zurich, Munich, Rotterdam, and

Mexico City, before returning to the United States for additional venues.

Impressively energetic for man in his eighties, he continued to travel

extensively, lecture widely, and write prolifically. He was still actively

involved with all aspects of work including frequent trips to New York to

oversee construction of the Guggenheim Museum when, in April of 1959, he was

suddenly stricken by an illness which forced his hospitalization. He died April

9, two months shy of his ninety-second birthday.

STYLE & DESIGN

Wright’s style and design

changed as he responded to the needs of American society,

Wright

opened his last decade with work on a large exhibition, Frank Lloyd

Wright: Sixty Years of Living Architecture, which was soon on an

international tour traveling to Florence, Paris, Zurich, Munich, Rotterdam, and

Mexico City, before returning to the United States for additional venues.

Impressively energetic for man in his eighties, he continued to travel

extensively, lecture widely, and write prolifically. He was still actively

involved with all aspects of work including frequent trips to New York to

oversee construction of the Guggenheim Museum when, in April of 1959, he was

suddenly stricken by an illness which forced his hospitalization. He died April

9, two months shy of his ninety-second birthday.

USONIAN

Responding to the

financial crisis of 1929 and ensuing Great Depression that gripped the United

States and the rest of the world, Wright began working on affordable housing,

which developed into the Usonian house. Wright’s Usonians were a simplified

approach to residential construction that reflected both economic realities and

changing social trends. In the Usonian houses, Wright was offering a

simplified, but beautiful environment for living that Americans could both

afford and enjoy. Wright would continue to design Usonian houses for the rest

of career, with variations reflecting the diverse client budgets.

PHILOSOPHY

DESIGN FOR DEMOCRACY

Wright always aspired to

provide his client with environments that were not only functional but also

“eloquent and humane.” Perhaps uniquely among the great architects, Wright

pursued an architecture for everyman rather than every man for one architecture

through the careful use of standardization to achieve accessible tailoring

options to for his clients.

INTEGRITY &

CONNECTION

Believing that

architecture could be genuinely transformative, Wright devoted his life to

creating a total aesthetic that would enhance society’s well being. “Above all

integrity,” he would say: “buildings like people must first be sincere, must be

true.” Architecture was not just about buildings, but about nourishing the

lives of those within them.

NATURE’S PRINCIPLES &

SCULPTURES

For Wright, a truly

organic building developed from within outwards and was thus in harmony with

its time, place, and inhabitants. “In organic architecture then, it is quite

impossible to consider the building as one thing, its furnishings another and

its setting and environment still another,” he concluded. “The spirit in which

these buildings are conceived sees all these together at work as one

thing.” To that end, Wright designed furniture, rugs, fabrics, art glass,

lighting, dinnerware, and graphic arts.

MATERIAL & MACHINE

Wright embraced new

technologies and tactics, constantly pushing the boundaries of his field. His

fascination for the new and his desire to be a pioneer help explain Wright’s

tendency to test his materials—sometimes even to the brink of failure—in an

effort to achieve effects he could claim as uniquely his own.

ARCHITECTURE AS THE GREAT

MOTHER ART

Wright devoted his life

to promoting architecture as “the great mother art, behind which all others are

definitely, distinctly and inevitably related.” Seeking a consistent expression

of underlying unity, he drew inspiration from the Japanese idea of a culture in

which every object, every human, and every action were integrated so as to make

an entire civilization a work of art. Above all else, Wright’s vision served

beauty. He believed that every man, woman and child had the right to live a

beautiful life in beautiful circumstances and he sought to create an affordable

architecture that served that aspiration.

WRITINGS

Fundamental to

understanding Wright’s work, his writings allow readers to see into his

creative mind through an intimate lens.

Wright’s own texts are a

testament to the fact that his ability to articulate himself matched his genius

with brick, concrete and glass. His books offer readers an exclusive glimpse

into the life and work of the complex architect.

http://franklloydwright.org/frank-lloyd-wright/