LA CITE DU VIN: WINE MUSEUM IN BORDEAUX DESIGN BY XTU ARCHITECTURE

AUDACIOUS

CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE BY XTU

The

architecture and scenic design of La Cité du Vin are the fruit of a close

partnership between two firms: Parisian architects XTU and English museum

design experts Casson Mann. Their project – which combines a bold, poetic

interpretation of the spirit and intangible cultural power of wine with a raft

of immersive digital technologies – wowed the judging panel during the call for

tenders launched by commissioning authority the City of Bordeaux in late 2010.

This tender procedure required candidates to form architect-designer

partnerships to ensure that the structure and its content were part of a

single, cohesive project. A total of 114 submissions were received, 5 projects

were short-listed and 1 winner was ultimately chosen: XTU and Casson Mann, in

association with Canadian engineering form SNC Lavalin. GTM Bâtiment Aquitaine,

a subsidiary of Vinci Construction France, was then selected as the project’s

designated construction partner.

AUDACIOUS

CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE

The

architects from Parisian agency XTU, Anouk Legendre and Nicolas Desmazières,

have imagined a structure replete with symbolic echoes: the swirl of wine

moving in a glass, the coiled movement of a grapevine, the ebb and flow of the

Garonne... Their design captures the spirit of wine and its fluid essence: ‘a

seamless curve, intangible and sensual’ (XTU Architects) which addresses its

multiple environment. Horizontal and vertical lines are linked in a unique

continuous motion growing out of the soil along a large boardwalk ramp. More a

movement than a shape, it releases and reveals itself as it rises, creating an

event amid the landscape that connects with the bridge and river.

AN

INNER ‘ SOUL ‘

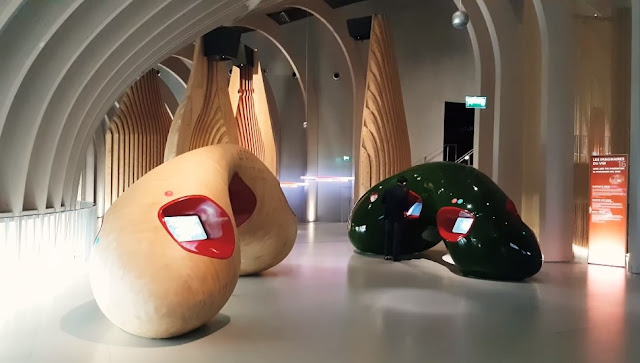

This

curve, matching the curve of the Garonne, is also reflected in the interior

volumes, spaces and materials. La Cité du Vin houses a major space in the shape

of the permanent tour on the second floor, an immersive voyage of discovery

into the world of wine. It winds around a central courtyard, allowing visitors

to enjoy a flowing visit to the full. The area is framed by a spectacular and

immersive wooden structure: 574 curving arches, all individually made,

constructed of laminated timber. These wooden arches continue up the tower to

the belvedere level in 128 spines, culminating at a height of 55 metres and

tying the whole space together by interlacing the different floors. They

accompany the visitor’s path at different levels, emerging on the outside of

the building as they rise up the tower. The iconic indoor spaces all have their

own particular identities, from the Thomas Jefferson Auditorium with its

ceiling of suspended wooden tubes and the belvedere with its mirrored bottle

ceiling to the immersive multi-sensory room with its curved glass walls printed

with large wine-based designs.

A

CONSTANTLY CHANGING APPEARANCE

Once

fully grown, La Cité du Vin will be a dazzling display of golden reflections,

reminiscent of the white stone of Bordeaux facades and in dialogue with the

lights of the Garonne. This design and the twists it incorporates capture a

fluid essence. Its outer structure consists of custom-printed glass panels

(both flat and curved) in a variety of colours, and lacquered, iridescent

aluminium panels in a single colour. The different, constantly changing shades

and angles of these panels give the building an appearance which develops with

the Bordeaux sky: reflections of the clouds, the city and the water enhance La

Cité du Vin’s evocative appearance. Set a distance away from the structure,

this shell offers shade from the sun and effective thermal protection.

Innovative

tools to achieve an aim

The XTU

agency’s use of innovative design tools to develop the geometry and complex

shell helped to perfectly capture the architects’ mental image of La Cité du

Vin and transform it into a sensational project.

https://www.laciteduvin.com/en?gclid=Cj0KCQjwxvbdBRC0ARIsAKmec9apKto_MeUwCKiu4C_x00QY8TMG46crd8_OmMmqDXEICG0Dr1hE3jgaAr5tEALw_wcB

THE

PERMANENT TOUR

VÉRONIQUE

LEMOINE

Director

of the permanent tour of

the

Fondation pour la culture et les civilisations du Vin

At the

heart of the visitor experience and the identity of La Cité du Vin, the

immersive, multi-sensory permanent tour occupies some 3,000 m² and features 19

different themed spaces, the majority of which are interactive. Visitors are

free to wander around the exhibition space as they see fit, with no fixed,

compulsory route. The permanent tour is an invitation to a voyage of discovery,

a journey through time and space exploring the evolution of wine and its

civilisations. Young and old alike will get to grips with the very rich

imaginary world of wine and how it has affected the societies and regions of

the globe for millennia, from 6,000 BC to the present day. From legends,

terroirs and landscapes to graphic arts, architecture and literature, the

culture of wine is an extraordinary epic which has inspired and shaped the

lives of humans for centuries.

The

permanent tour allows the visitor to wander freely. Visitors can browse around

at will, depending on their interests and the time at their disposal. As a

participant or a spectator, sitting or standing, they can alternate between

experiences which may be individual, collective, informative, fantasy or

multi-sensory. Everyone is free to organise their own individual visit.

Visitors

are joined on this odyssey by their personal handheld guide, connected to an

innovative device which detects the wearer’s position within the exhibition

space and sets of the appropriate multimedia content. The digital guide

delivers the explanatory dialogue in real time in the user’s selected language

(8 languages available), ensuring that as much of the material as possible is

available to visitors with (visual, auditory or cognitive) disabilities. The

guide also features a specially-designed programme for younger visitors.

Visitors can also use the personal digital guide to highlight their favourite

moments in the exhibition experience, and at the end of their visit they will

be presented with a personalised information booklet filled with opportunities

to learn more about their chosen subjects.

CHATEAU MARGAUX

CHATEAU

MARGAUX

PRUNING

Pruning

is essential. That is what the production quality and the longevity of the

plots depends on. Indeed, the number of buds per plant determines the delicate

balance of the vigour; pruning that leaves too many buds leads to a harvest

that is too abundant and unable to ripen sufficiently. Conversely, pruning that

is too severe leaves vines that are too vigorous, encouraging excessive growth

to the detriment of the maturity of the grapes.

There is, not only for each plot, but for each grape variety, an optimal balance that only winegrowers understand with experience.

Winter pruning extends into the spring by a green pruning and bud-thinning. This means avoiding a build-up of vegetation that is harmful to the exposure of future grape clusters to the sun and as well to concentrating the nutrients produced by the leaves towards the branches that support the grapes, which encourages ripening. Lastly, bud-thinning enables the winegrowers to select future branches for thinning in advance.

There is, not only for each plot, but for each grape variety, an optimal balance that only winegrowers understand with experience.

Winter pruning extends into the spring by a green pruning and bud-thinning. This means avoiding a build-up of vegetation that is harmful to the exposure of future grape clusters to the sun and as well to concentrating the nutrients produced by the leaves towards the branches that support the grapes, which encourages ripening. Lastly, bud-thinning enables the winegrowers to select future branches for thinning in advance.

PLANTING

Great

wines are always produced from vines that are at least twenty years old. So the

main objective of our wine-growing practices is to maintain the old vines in

production for as long as possible. But their life expectancy doesn’t always

fulfill our hopes... In particular, the Cabernet Sauvignon variety, the heart

of our vineyard and the soul of our wine, has a very high mortality rate.

The main solution is to replace the plants, one by one, as and when they die. This is called “complantation”. This practice, as old as the vineyard, occupies all our winegrowers for two months just after the winter pruning. We replace between 10,000 and 15,000 plants per year! But it’s only at the price of this lengthy work that we’re able to maintain the high density of planting in our plots (10,000 plants per hectare); this allows the harmonious management of the vigour of the vines.

The complants themselves have a limited life expectancy... At the end of the day, it’s the whole plot that expires. So we then have to carry out a complete renewal. What a sacrifice! First, we have to pull up all the vine stocks and then let the soil rest for six years. Finally, we replant it and wait until these new vines grow and age in order to produce great wine.

The main solution is to replace the plants, one by one, as and when they die. This is called “complantation”. This practice, as old as the vineyard, occupies all our winegrowers for two months just after the winter pruning. We replace between 10,000 and 15,000 plants per year! But it’s only at the price of this lengthy work that we’re able to maintain the high density of planting in our plots (10,000 plants per hectare); this allows the harmonious management of the vigour of the vines.

The complants themselves have a limited life expectancy... At the end of the day, it’s the whole plot that expires. So we then have to carry out a complete renewal. What a sacrifice! First, we have to pull up all the vine stocks and then let the soil rest for six years. Finally, we replant it and wait until these new vines grow and age in order to produce great wine.

FROSTS

Among

all the risks that are the farmers’ lot in life, frost and hail are the two

most terrible and unfair. In just a few minutes they can reduce to nothing a

whole year, or even several years’ efforts. But by some sort of miracle, the

great terroirs more often than not, escape these misfortunes. Hail is almost

unknown at Château Margaux.

Why ? We really don’t know. On the one hand, if frost misses the greater part of our vineyard, it’s thanks to its particular situation, close to the river where the thermal inertia protects its surroundings from the cold and is sufficiently elevated to escape the accumulation of masses of icy air. Every rule has its exceptions… our white plot presents such a sensitivity to spring frosts that we decided, as of 1983, to install an anti-frost system. The principle is simple: we spray the vines with water for as long as the frost lasts, generally until dawn. The heat produced by the formation of ice enables the maintenance of the temperature above the limit below which the vegetation is destroyed. Before starting the sprinklers, we have to take into account the temperature, the wind and the air humidity, and all this at three o’clock in the morning! When the decision has been taken, in spite of fatigue, it’s a huge consolation to save the harvest and to be present at the fairy-like show given by the ice as it forms around the buds.

Why ? We really don’t know. On the one hand, if frost misses the greater part of our vineyard, it’s thanks to its particular situation, close to the river where the thermal inertia protects its surroundings from the cold and is sufficiently elevated to escape the accumulation of masses of icy air. Every rule has its exceptions… our white plot presents such a sensitivity to spring frosts that we decided, as of 1983, to install an anti-frost system. The principle is simple: we spray the vines with water for as long as the frost lasts, generally until dawn. The heat produced by the formation of ice enables the maintenance of the temperature above the limit below which the vegetation is destroyed. Before starting the sprinklers, we have to take into account the temperature, the wind and the air humidity, and all this at three o’clock in the morning! When the decision has been taken, in spite of fatigue, it’s a huge consolation to save the harvest and to be present at the fairy-like show given by the ice as it forms around the buds.

PLOUGHING

We

intentionally keep the work of the land traditional, although a great part of

it is carried out by high-clearance tractors and equipment that is of

ever-increasing efficiency. Our four ways of ploughing: surfacing and

desurfacing, surfacing, desurfacing rhythmically throughout the farming year is

done in an almost unchanging way. It’s true that our soils, generally light and

well-structured thanks to regular addition of manure, lend themselves well to

this superficial work.

More strangely perhaps, we continue, twice per year, to remove the “cavaillons” by hand. This consists of loosening the coating of soil left around the vine stocks by the ploughs.

Our interest in research doesn’t only apply to new techniques, but also the old, traditional ones. For that reason, we are currently conducting some ploughing experiments with a horse. We would like to be able to draw on years of experience before returning to that method of ploughing, should that be the case.

More strangely perhaps, we continue, twice per year, to remove the “cavaillons” by hand. This consists of loosening the coating of soil left around the vine stocks by the ploughs.

Our interest in research doesn’t only apply to new techniques, but also the old, traditional ones. For that reason, we are currently conducting some ploughing experiments with a horse. We would like to be able to draw on years of experience before returning to that method of ploughing, should that be the case.

PROTECTION

OF THE VINES

Obtaining

grapes that are ripe enough presupposes a perfect control of the phyto-sanitary

condition of the vineyard. During the last thirty years, the quality of

treatment products, their efficiency and their ease of use, hasn’t stopped

improving. The power and precision of the new spraying equipment have also

contributed a great deal to this success.

Mildew, powdery mildew, black-rot, excoriation, almost all fungal diseases, with the notable exception of the wood diseases, esca and eutypiose, that particularly affect the Cabernet Sauvignon variety, are now well controlled. Powdery mildew is controlled by sulphur and mildew by spraying copper sulphate, the famous “Bordeaux mixture”.

The case of grey rot (Botrytis cinerea) is certainly more delicate, but the low instance of vigour in our vines and their traditional behaviour create rather unfavourable conditions for the development of this disease.

The problem presented by parasites, insects and spiders is complex in a different way. In the nineteen eighties we questioned all of our vineyard protection policy with the objective of finding an alternative method to chemicals to preserve the balance of the spider and insect populations. After a few years of work, we were able to stabilise the situation. Since then, all these populations cohabit and autoregulate themselves without us having to take any action, or only in an organic way. At the end of the nineteen nineties, sexual confusion was developed in order to stop the grape worms reproducing. Not one insecticide is now used in our vineyards.

Mildew, powdery mildew, black-rot, excoriation, almost all fungal diseases, with the notable exception of the wood diseases, esca and eutypiose, that particularly affect the Cabernet Sauvignon variety, are now well controlled. Powdery mildew is controlled by sulphur and mildew by spraying copper sulphate, the famous “Bordeaux mixture”.

The case of grey rot (Botrytis cinerea) is certainly more delicate, but the low instance of vigour in our vines and their traditional behaviour create rather unfavourable conditions for the development of this disease.

The problem presented by parasites, insects and spiders is complex in a different way. In the nineteen eighties we questioned all of our vineyard protection policy with the objective of finding an alternative method to chemicals to preserve the balance of the spider and insect populations. After a few years of work, we were able to stabilise the situation. Since then, all these populations cohabit and autoregulate themselves without us having to take any action, or only in an organic way. At the end of the nineteen nineties, sexual confusion was developed in order to stop the grape worms reproducing. Not one insecticide is now used in our vineyards.

THINNING

In 1986, Château Margaux was the first vineyard in the Médoc to practise thinning, which consists of removing a certain number of clusters before the start of the ripening period. In most of the young vines, the harvest in practice is too abundant to produce a quality wine; by reducing them at their mid-term, that is to say just before they change colour about the beginning of August, we encourage the ripening of the other clusters left on the vine, without increasing the vigour of the plant.

In 1986, Château Margaux was the first vineyard in the Médoc to practise thinning, which consists of removing a certain number of clusters before the start of the ripening period. In most of the young vines, the harvest in practice is too abundant to produce a quality wine; by reducing them at their mid-term, that is to say just before they change colour about the beginning of August, we encourage the ripening of the other clusters left on the vine, without increasing the vigour of the plant.

This technique also allows us to select the best clusters and to eliminate

those that are badly placed on the vine, or that are already late compared to

the others. It is work that is really meticulous and differs for each vine,

grape by grape, which gives a good idea of the increasingly precise and

rigorous attention given to the care of the vineyard.

YIELD

The

yield from the vines, expressed by their production (kilos of grapes or

hectolitres of wine) is a key factor in the quality of the grapes. Too abundant

a harvest never ripens because the vines become exhausted for no other reason

than trying to feed too many clusters at once. In order to protect the quality

of the wine and the longevity of the vines, the Margaux appellation has fixed a

limit that is in general the most restrictive in the Médoc.

TRELLISING

The

very high density of the plantation in our vineyard (10,000 plants per hectare)

would lead very quickly to an impossible tangling of the branches if we didn’t

provide a good trellising. Primary objectives are to allow free circulation

between the rows, on foot or by tractor, and to maximize the exposure of the

clusters to the sun, a factor so necessary to their optimal ripening.

The trellising consists of two successive steps: first, lifting of the branches. That is done thanks to a set of mobile wires that we pick up as and when the vine grows. Then the cutting, or “topping”, of the tips of the branches, carried out mechanically by a piece of equipment on the overhead clearance tractors.

The trellising consists of two successive steps: first, lifting of the branches. That is done thanks to a set of mobile wires that we pick up as and when the vine grows. Then the cutting, or “topping”, of the tips of the branches, carried out mechanically by a piece of equipment on the overhead clearance tractors.

RIPENING

The

acquisition of the grapes in a perfect state of ripeness is the precondition

for producing a great wine; consequently, all our winegrowing practices are

directed toward this objective. But by far and away the most important factor

is the terroir: it’s their aptitude to enable the wine varietal to ripen well

that distinguishes the greatest growths. To enable a grape to ripen “well” is

to ensure that its components, that is to say sugar, acidity, aromas and

tannins, evolve together at the same pace. In the Bordeaux region, we’re lucky

enough to enjoy a temperate climate and a moderately rich soil, allowing the

vines to accompany the grapes in this effort to create the perfect balance.

MANURE

The

objective of manure is to bring to the vine the nutrition that it needs,

without excess that would increase the vigour to the detriment of the quality

and in respect to the environment.

A manuring process known as “deep manuring” can also sometimes be applied as a preamble to a new plantation. Its objective is to restore structure and life to the soil. In all cases, we only use organic fertilisers that integrate naturally into the environment. A large part of this is brought in the form of bovine manure, produced by our herd and composted for at least a year.

A manuring process known as “deep manuring” can also sometimes be applied as a preamble to a new plantation. Its objective is to restore structure and life to the soil. In all cases, we only use organic fertilisers that integrate naturally into the environment. A large part of this is brought in the form of bovine manure, produced by our herd and composted for at least a year.

HARVEST

At the

end of the year’s work comes, at last, harvest time. Everything is finished, or

nearly finished: the ripening is completing “August develops the must”, the

great balances are happening, or not, in the grapes. However, a bit of suspense

remains, because it’s in these last days that a good vintage still has a chance

of becoming great. First, we have to choose the date, examine the grapes and

analyse them, squeeze them, feel under our fingers and our tongue the softness

of the pulp and the firmness of the tannins; ignore the big clouds rolling

around in the sky in order to gain several more days and allow the Cabernet

Sauvignon to finally reach perfect ripeness. In the meantime, we’ve formed our

two hundred pickers into five teams, each made up of wine growers, and a

majority of young students, who, instead of experience, bring us their

willingness and their good humour. The pickers, more than half of whom come

back year after year, receive training.

Here they are now, working hard in our plots. First, the Merlot, always earlier, then the Cabernet Franc, and finally the Cabernet Sauvignon and Petit Verdot, always later. The thinning operations in the summer have already allowed us to dispose of the unwanted clusters but a last rigorous sorting is imperative. The responsibility comes back directly to each picker and then to a specialist team for a final sorting before the grapes are destemmed.

Here they are now, working hard in our plots. First, the Merlot, always earlier, then the Cabernet Franc, and finally the Cabernet Sauvignon and Petit Verdot, always later. The thinning operations in the summer have already allowed us to dispose of the unwanted clusters but a last rigorous sorting is imperative. The responsibility comes back directly to each picker and then to a specialist team for a final sorting before the grapes are destemmed.

http://www.chateau-margaux.com/en/savoir-faire/travail-vigne/gerbaude

CHATEAU MARGAUX

WINE

AND MUSIC, HARMONY AND DISSONANCE ( 16th - 19th CENTURY

)

( PASR EXHIBITION NEWS )

For its

second major artistic exhibition, La Cité du Vin reveals the richness of the

links between music and wine through a sensitive, audiovisual journey, which in

turn calls to mind the arts of painting, music and the stage. From the Renaissance

to the end of the 19th century, reminders of the association between wine and

music, inspired by antiquity, are numerous and appear in renewed forms in all

circles, whether princely, bourgeois or popular. Dionysus (Bacchus for the

Romans) is the god of wine and of creative inspiration. In its allegorical

forms, music is itself frequently associated with wine, love and sensuality.

Based on the custom of amorous meals in songs and the conviviality of banquets,

taverns and cabarets, the alliance of wine and music goes back centuries and

finds expression in all social strata. We find these mythical and symbolic

references at the heart of great pictorial works, but also in popular imagery,

the decoration of everyday objects, in ballets and operas as well as in

repertoires of songs, either published or in the oral tradition. The exhibition

reflects this profusion through six themed sections and nearly 150 works from

French and European collections. Recordings of operas, excerpts of ballets and

unpublished drinking songs are offered for listening and form musical

interludes along the journey.

DIONYSUS:

TRIUMPHS & BACCHANALIAN PROCESSIONS

Dionysus

was the fruit of the illicit love between Zeus and Semele, daughter of the king

of Thebes. Brought up in secret, after lengthy wandering in the East, he

returned to Greece to be recognised. An ambivalent god, he was a benefactor

when he gave men the gift of the vine, but he also had a wild and even violent

dimension. Relief sculptors and painters of ancient drinking vessels largely

chose the joyous and beneficent character of the young god. In his festive

procession (thiasus), he is usually portrayed wearing a long chiton (long linen

tunic) and a panther skin, holding a kantharos (vase with high handles to drink

the wine) in one hand, and in the other a thyrsus (long stick covered with ivy

leaves or topped with a pine cone). He is accompanied by maenads (bacchantes

for the Romans) who personify the trance and the orgiastic spirits of nature.

Dressed in panther skin, equipped with a thyrsus and tambourine, they perform

convulsive dances with satyrs who are often musicians. These triumphs were of

great inspiration to the painters of the Renaissance, who give sensual,

exuberant and sometimes parodic interpretations. The decoration of refined

objects, but especially the official processions of princes, court spectacles

(Lully in the 17th century), those of the elite (Massenet late 19th and early

20th century), but also those of the street, have been inspired by them over the

centuries.

https://www.laciteduvin.com/en/experience-la-cite-du-vin/temporary-exhibitions/wine-and-music-harmony-and-dissonance

DANCE:

BACCHANALIA, BALLETS, POPULAR DANCES

The

very spirit of dance is embodied in the ambivalent figure of Bacchus, the god

of feasting, transgression, excessive and indecent joy provoked by drunkenness.

Dance is a symbol of lasciviousness, but it is also an initiatory ritual both

in its ancient and mythological reference and in its later social uses: in

modern times, the ideal aristocratic education could not do without dance.

Carnival and the seasonal festivals during which most ballets and masquerades

were danced, are based on features of the ancient cult (bacchanalia and

saturnalia): processions, floats, dressing up and masks hold a

large place in them. Here we transgress the established order, the hierarchies,

the social rules and decorum through acclamations of joy and excesses. The

heroic ballet, of which Rameau was the champion in the 18th century, continued

with the elite tradition in Paris at the Académie royale de musique, and later

at the opera with Massenet in the early 20th century. Across the centuries, the

branles, popular urban or village dances that celebrated royal events such as re-found

peace, have associated the consumption of wine with the use of instruments

suitable for dancing outdoors.

LOVE

& DRUNKENNESS

Wine

associated with love exalts sensuality and pleasure. The gods were the first to

succumb to it, as illustrated by many representations blending wine consumption

and eroticism, sometimes coming close to the image of the brothel. The story of

Dionysus, god of wine, consoling Ariadne, abandoned by her lover Theseus on the

island of Naxos, has also known great success in painting and in music. In the

17th century, entertainments in the court of the young Louis XIV exploited this

vein, that makes wine the auxiliary of love. Through the feast of Bacchus, it

is Love that is celebrated. The success of these creations can be measured by

the number of popular parodies that circulated afterwards. Licentious love is

omnipresent in pictorial works showing the effects of drunkenness in small

cafés and low-life places, especially among the painters of the North such as

Dirck van Baburen or Gerrit van Honthorst. Among the engravers, popular scenes

show urban entertainment in which intemperance and transgressions are hardly

repressed by the authorities.

CHARACTER

FIGURES & ALLEGORIES

Many

artists represent wine and music in allegorical or moralising compositions. The

isolated figure of the intoxicated musician or the Drinking musician is a motif

that is very popular among northern painters in the early 17th century. The

most prolific are Gerrit van Honthorst, Dirck van Baburen and Hendrick ter

Brugghen. Their characters, represented at half-length, are always of humble

extraction. They hang out in taverns and lowlife places. They can sing along

with a lute, or hold a violin in one hand and a full or upturned glass in the

other. The feathered hat, an attribute of love, frivolity and sensuality,

characterises their clothing. To express the Five Senses painters also offer

individual human figures bearing an attribute, or a series of five subjects in

the most sought-after staging. Another proposal is to portray the Five Senses

by skilfully using the excuse of a banquet to associate the stereotypes of a

musician (Hearing), a wine drinker (Taste), an admirer caressing a courtesan

(Touch), a coquettish woman (Sight) and a smoker (Smell). The Still life allows

a more restrained approach, less immediately sensual, but more meditative. It

may seem at first glance to praise the pleasures of life, but with subtlety it

reveals a more complex message, ambivalent and often moralistic. The border

between still life and vanity thus appears very tenuous.

https://www.laciteduvin.com/en/experience-la-cite-du-vin/temporary-exhibitions/wine-and-music-harmony-and-dissonance

PHILIPPE JAROUSSKY: '' SOVENTA IL SOLE '' - VIVALDI

CONCERTS

& AMOROUS MEALS

Music

and wine are frequently associated in scenes involving couples around a table.

The meal is almost finished but still visible. The music books have just been

opened, the couples intertwine and serve each other wine while others play and

sing in perfect harmony. From the end of the Renaissance, these scenes have

inspired painters, engravers and also the master decorators of keyboard

instruments. They evoke shared sensual pleasures, temperance, but sometimes

also, in an elegant and restrained vein, the parable of the Prodigal Son with

the fallen women. It was around these tables that a considerable repertoire of

serious music and drinking songs circulated in the educated circles of the

aristocracy and the wealthy bourgeoisie. They were either collected in

handwritten form, with amateurs recording their own favourites, or printed.

They were a flourishing speciality of both composers and printers in the 17th

and 18th centuries.

BANQUETS,

TAVERNS & CABARETS

Other

sociability exists around the table: that of the tavern, joyful or melancholy,

that of the inn, with consumption in the open air, or that of places devoted to

regulars who formed societies like the Chambers of rhetoric in Flanders or the

singing societies that developed in the 18th and 19th centuries. Some were

relatively closed, ritualised and literary (such as the famous Caveau which

flourished for two centuries), while others were more democratic, feminised and

popular, like the workers’ goguettes. A crucible for many literary creations in

the first case, home of a social and political identity in the other, these

places had in common the song and the consumption of wine around variously

laden tables. Here, the repertoire circulated in the form of very inexpensive

collections where the lyrics are associated with well-known tunes called

timbres. Their conscientious collection built up a repertoire that continued to

be practised until the Second World War. The stereotypes and the imagination of

these places are echoed skilfully in many operas and comic operas, where they

contribute to the drama and the entertainment.

https://www.laciteduvin.com/en/experience-la-cite-du-vin/temporary-exhibitions/wine-and-music-harmony-and-dissonance

VISITER

LA CITÉ DU VIN

Located

in Bordeaux, La Cité du Vin is a unique cultural facility dedicated to the

universal, living heritage of wine. It offers a spectacular journey around the

world, throughout the ages across countless cultures and civilisations. La Cité

du Vin has become an essential feature in the Bordeaux tourist circuit, but is

also a lively social venue for the inhabitants of Bordeaux and its surrounding

area. La Cité du Vin is a place to see, visit and experience.

The

architecture and scenic design of La Cité du Vin are the fruit of a close

partnership between two firms: Parisian architects XTU and English museum

design experts Casson Mann. Their project combines a bold, poetic

interpretation of the spirit and intangible cultural power of wine, with a raft

of immersive digital technologies.

At the

heart of the visitor experience and the identity of La Cité du Vin, the

immersive, multisensory permanent tour occupies some 3,000 m² and features 19

different themed spaces, the majority of which are interactive. Visitors are

free to wander around the exhibition space as they see fit, with no fixed,

compulsory route. Located on the eighth floor of La Cité du Vin, the belvedere

is perched at a height of 35 meters. The culmination of a visit to the

permanent tour, it invites visitors to discover the Gironde city and surrounding

area with a 360° perspective and taste a glass of wine from the very best wine

regions of the world.

In

addition to this tour, visitors can take advantage of wine culture workshops to

learn about the art of tasting with a cultural approach, or a journey through

the terroirs and know-how of the world in the multi-sensory area to awaken the

five senses. A true cultural facility, La Cité du Vin offers two major

temporary exhibitions per year as well as a varied cultural programme.

Encounters and debates, shows and festivities, terroir weekends, screenings,

and colloquia, La Cité du Vin is the cultural crossroads of the city of

Bordeaux.

A venue

open to all, La Cité du Vin offers numerous public areas hosting life and

exchange. Visitors can discover the building, take advantage of the landscaped

garden next to the Garonne, have a bite to eat, head to La Boutique, or spend a

while in the reading room perusing the various books and multimedia items for

reference use.

La Cité

du Vin is run by the Foundation for Wine Culture and Civilisations. An

accredited charitable organisation since December 2014, the primary purpose of

the Foundation for Wine Culture and Civilisations is to protect, celebrate and

transmit the cultural, historic and intellectual dimensions of wine. The

Foundation depends entirely on takings from La Cité du Vin and patronage

donations, which thus play a crucial role in the economic model.

https://www.laciteduvin.com/en/experience-la-cite-du-vin/temporary-exhibitions/wine-and-music-harmony-and-dissonance

CHATEAU MOUTON ROTHSCHILD

THE

MOUTON STYLE

The ambition of making Mouton a place of art and beauty can be seen everywhere. Outside, in the harmonious arrangement of buildings and open space, in the subtle play of perspectives, in the zen-raked pathways, in the peaceful symmetry of the two end-walls that frame the château, in the contrast between the vertical lines of Petit Mouton, a modest, ivy-covered, mansard-roofed Victorian residence built in 1885, and the horizontal lines of Grand Mouton, constantly enhanced and redesigned since the 1960s.

The ambition of making Mouton a place of art and beauty can be seen everywhere. Outside, in the harmonious arrangement of buildings and open space, in the subtle play of perspectives, in the zen-raked pathways, in the peaceful symmetry of the two end-walls that frame the château, in the contrast between the vertical lines of Petit Mouton, a modest, ivy-covered, mansard-roofed Victorian residence built in 1885, and the horizontal lines of Grand Mouton, constantly enhanced and redesigned since the 1960s.

Grand Mouton symbolises a whole art of living, and hence of

receiving guests. It contains several large rooms: the Column Room and its Old

Master paintings celebrating the vine and wine; the Dunand Room, in tribute to

the famous lacquer artist, who around 1930 created a harvest dance for the

liner Normandie; the Ramp Room with its sloping ceiling, its

statues and its tapestries. After the Grand Chai and its precious casks,

the Museum of Wine in Art, situated in a former

barrel hall, is a sight of splendour, containing exceptionally rare items of 17th-century German gold- and silverware, jugs, cups

and goblets from the fabulous treasure of the kings of Naples, antiques,

mediaeval tapestries, paintings, ivories, glassware, Chinese, Japanese and

Persian porcelain and much more. An unforgettable experience, it is a magical

place where so many artists and art forms, cultures and religions bear

resounding witness to the eternal and fruitful dialogue between art and wine.

https://www.chateau-mouton-rothschild.com/the-house/the-mouton-style

PABLO

PICASSO

We have to approach art as immediate as that of Picasso in a

way that is entirely direct, honest, spontaneous and innocent… What we

absolutely must not do is put him on a pedestal like some horror in a cemetery

and talk about him as “a great man”: everything about him is alive, in constant

movement, refusing to be confined in a lifeless statue. One of the grossest

errors propagated about Picasso, and one we hear most often, is the idea that

he is something to do with the Surrealists. In fact, in the majority of his

paintings, the subject is almost always completely down to earth, never drawn

from the dim world of dreams, never capable of being turned into a symbol, in

other words not in any way Surrealist. Human limbs, human subjects in human

surroundings; that is first and foremost what we find in Picasso.

Michel Leiris, Document 2, 1930.

Nothing can be done without solitude. I have created solitude

for myself no-one ever dreams exists. It’s very difficult to be alone nowadays

because we have wristwatches. Have you ever seen a saint with a wristwatch?

I’ve looked everywhere and I haven’t been able to find a single one, not even

on saints who are meant to be the patron saints of clockmakers

Picasso to Tériade, 1932.

GEORG

BASELITZ

CHATEAU MOUTON ROTHSCHILD

LA CITE DU VIN: WINE MUSEUM IN BORDEAUX DESIGN BY XTU ARCHITECTURE

LA CITE

DU VIN BOUTIQUE

The

Boutique is a modern, stylish 250m² space which mirrors the golden reflections

of the façade of La Cité du Vin, with tailored designer fittings. The store can

be accessed without an admission ticket, and offers a selection of items from

all around the world: decorative objects made from materials used in the world

of wine, such as barrel staves or corks, a range of beauty products showcasing

the benefits of vine products, edible treats, candles and lights, a wide

selection of books, comics, and mangas on the theme of wine, stationery, and a

selection of crockery and wine tasting items.

NIETZSCHE’S

DIONYSOS

DIETER

MERSCH ZURICH UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS

In his

considerations on an aesthetic of erscheinen1, which also incorporate Dionysus

in the title, Karl Heinz Bohrer asserts his thesis that Nietzsche’s figuration

of the Dionysian advances an aesthetic of In-Erscheinung-treten2—and that, if

anything, Dionysus is in actuality first and foremost in representing the god

of erscheinen (appearance). He combines two further theses with that as well:

First, that Nietzsche conceptualizes his work on the tragic—in which he

introduces the opposition between the Dionysian and Apollonian as the polar

struggle of artistic forces—not principally as a theory of the aesthetic but

instead as a “life doctrine” (Lebenslehre), which at its core is, as he puts

it, “the elementary, materialistic celebration of the life impulse (Lebensimpuls)

and [the] undermining of idealistic presuppositions such as rationality,

substance, subject” (Bohrer 2013,13).3 Secondly, Bohrer continues, wherever

this life doctrine is applied to the aesthetic, it primarily represents an

“aesthetic of the sublime,” without ever making clear whether it should be

understood “in terms of the theory of reception or the aesthetics of

production” (rezeptionstheoretisch oder produktionsästhetisch) (Bohrer 2013,

15).4 It is not my wish to contradict this, at least not completely, but rather

to effect a shift or re-accentuation of the basic underlying motif—whereby it

is important to recall once again that Nietzsche’s Dionysus, admittedly,

represents a direct provocation and an attack on the interpretation of the classics

accepted since Winckelmann, an interpretation that elevates the Apollonian to

its central point of focus; Nietzsche’s introduction of another principle to

oppose it, rather than representing a genuine invention, in actuality bridges

the small gap between Hegel and Hölderlin. If, namely, the Hegelian aesthetic

from the very beginning points to Schein and Erscheinung—as necessary

conditions of truth, for the truth would not exist if it were not to

“superficially appear” (scheinen) and “make its appearance” (erscheinen),

writes Hegel—Schein and Erscheinung would still nonetheless be bound up

everywhere with the criterium of the absolute; after all, the untruth of the

aesthetic rests squarely in the fact that it cannot do other than to draw upon

the language of Erscheinung. For Hölderlin, on the other hand, the Dionysian

advances to become a metapoetic symbol combining itself—the enigmatic and

continually transforming—with the practice of art.

Nietzsche

continues along these very same lines even while giving the metaphor a

thoroughly different twist. For if one wishes to express a formula describing

the dichotomy or the shift I am seeking to highlight, one would have to say

that, while Bohrer has a Romantic understanding of Nietzsche—or, to be more

exact, understands him to be the high point and peak of the Romantic, which

encompasses the aesthetic of the sublime and the “celebration of the life

impulse (Lebensimpuls)” and, most notably, the criticism of idealism, the

subverting of any accolades of the rational—Nietzsche still, however,

implements a number of characteristic conversions into the terminological

context that transport his art theory into an utter anti-Romanticism. With

that, the question arises as to ‘what’ Nietzsche means with Dionysus—who ‘his’

Dionysus is—and to what extent art even unfolds within him, within his form—as

opposed to his “beautiful appearance” (schönen Schein). In that, it will be

revealed that the key to the upheaval associated with this figure rests in

disaggregating a whole arsenal of terms constituting an exact, one-to-one

correspondence with the traditional art theory of the day, revolving around the

metaphor of the dream, the imagination and their dissolution, their

negation—something associated with a thoroughly other metaphoricity, namely,

that of violence, destruction and what one could call the “imposition of

differentiation” (Differenzsetzung). And if the former conceptualization proves

to be connected to a series of methods of form and process, the latter is

satisfied to avail itself of the figure of the caesura, of “dis-formation”

(Entstaltung) or resistance, whereupon the aesthetic concurrently discovers its

reflective principle. Nietzsche hardly implements this; rather, he just

indirectly insinuates it. As I hope to demonstrate, his art philosophy

discovers its anti-Romantic leanings in that, rather than bring to its zenith

something already applied long ago, it points to something in the future,

something other, something encompassing the innate need to break with tradition.

As is

well known, the Apollo/Dionysus coupling appears prominently in Nietzsche’s

work from 1871, dedicated to Richard Wagner and entitled The Birth of Tragedy.

Around the same time, in 1870, he penned his work The Dionysian Vision of the

World, in it reexamining the problem of aesthetic representation, which Hegel’s

aesthetic placed at the center of his art philosophy and which Romantic art

drove (trieb) to the very fringes of portraying what is impossible to

portray—and beyond (übertrieb5), recalling in particular the paintings of Henry

Füssli and William Turner—in a reversion to the approaches of the antique,

particularly the question of mimesis. Nietzsche broached the mimesis problem

not explicitly but rather masked within the dichotomous opposition of the

Apollonian and Dionysian. Both concepts, their complementarity as well as their

continual interplay, supersede that which, in terms of the aesthetics of

production, could be described as the actual core of the artistic process: the

genesis of something or, quite literally, its exposition (Darstellung6). And

that, according to Nietzsche, encompasses as a “double source” or “stylistic

opposition” (Nietzsche 1999a, 119, 46) both of the “artistic drives”

(Kunsttriebe) that “interweave” and “differ in their highest goals” (Nietzsche

1999a, 76, see also 14–15, 25–26, 59)— namely, the Dionysian and Apollonian, a

complex of leitmotifs that persist throughout Nietzsche’s entire philosophical

oeuvre even as they undergo numerous reinterpretations. He continues treating

them in Twilight of the Idols (i.e. Nietzsche 1998b, 185–187) as well as in

countless passages in his unpublished writings, especially those which stem

from the mid-1880s and are on the periphery of what he calls the “will to

power” (Willen zur Macht), whereby an increasing radicalization also becomes

apparent. At the very beginning of The Birth of Tragedy, we encounter the

expression “duplicity,” denoting what is still undecided (I will return to this

later). What is decisive, however, is that aesthetic representation, rather

than crumbling in its idea and Erscheinung as seemed immanent after Hegel,

emerges—to adapt Heidegger’s formulation—from a ‘struggle,’ a polemos or

polemic, chiefly encompassing form on the one hand while belonging to an excess

on the other, whereby “excess,” superficially speaking, signifies the Rausch7

or, in a Platonic sense, “mania” (creative madness) and, specifically speaking,

addresses the obsession of genius—or, to go even deeper, as is my aim,

addresses the “ecstasy,” a word evoking a slew of associations from the

protrusions of ‘Ex-istence’ (the very same word) through the budding of

materiality to that which we could, in a still highly abstract way, call ‘the

event.’

I will

now return once again to Nietzsche’s text on tragedy in order to unearth the

key characteristics. On the one hand, we see written there that the artwork is

“as equally Dionysian as it is Apollonian,” whereby Nietzsche speaks of “the

common goal of both drives (Triebe) […]” (Nietzsche 1999a, 28) and disparate

“ways to the creation of art” (Nietzsche 1999a, 128) so that the impression

arises that he is discussing an alternative—two fundamentally different

artistic processes yielding different kinds of works. Thus it literally attests

to an “opposition” (Nietzsche 1999a, 19), to artistic stances “which differ in

their deepest essence and highest goals” (Nietzsche 1999a, 76). On the other

hand, Nietzsche still emphasizes in the 1880s that both elements must first of

all come together in order to bring art into existence at all, though the way

they actually come together still remains unclear. Now the oppositional

dichotomy of the two forces—which never, of course, exist purely as forces or

urges on their own but instead foster energies allowing something to

emerge—owes its existence to a number of conceptual differentiations that

ascribe specific attributes to both the Apollonian and the Dionysian. In

reference to Apollo, talk centers on the illusion—the old mimesis problem as

discussed by Plato—as well as on the Traumbild or “dream-images” (Nietzsche

1999a, 15)—as classic metaphor for the phantasm, the imaginarium— and on the

“mask” (Nietzsche 1999a, 46), while in reference to the Dionysian it accords a

characteristic “ecstatic” celebration and “unmeasurable excess” (Nietzsche

1999a, 27, 128). In later years, these are positioned in even clearer

referential relationship to each other and delineated as subspecies of the very

same eccentricity; Nietzsche asks in Twilight of the Idols, “What is the meaning

of the conceptual opposition I introduced into aesthetics, between Apollonian

and Dionysian, both conceived as types of intoxication (Rausch)?” (Nietzsche

1998b, 48), whereby the answer to his question leaves no room for doubt that

dissociation or displacement distinguishes the Dionysian ecstasy as the primary

“basic aesthetic condition,” while the imaginary simply builds its corollary, a

corollary only defined upon the artistic nature (Kunsthaftigkeit) of art.

What

the Apollonian-Dionysian principle actually means, however, can only be

clarified in a juxtaposition of the two. For example, Apollo’s Telos—as we read

in the shorter text The Dionysian Vision of the World—is the form, the picture,

the statue (Nietzsche 1999a, 127), and its Gestaltung faithfully obeys the

“lovely semblance” (schönen Schein) (Nietzsche 1999a, 15) and its “law”

(Nietzsche 1999a, 26) of “measured limitation” (maassvolle[n] Begrenzung)

(Nietzsche 1999a, 16), as Nietzsche continues to maintain in The Birth of

Tragedy. In contrast, Nietzsche describes the Dionysian art or art

energy—initially deriving it, very true to Schopenhauer, from the “imageless

art of music” (Nietzsche 1999a, 14, also 21, 28–31, 76)—as emerging from the

“Spiel8 with the Rausch” (Nietzsche 1999a, 119–121, 130). But let us inquire as

to the meaning of Rausch—which, incidentally, is the attribute classically

assigned to Dionysius in the character of Bakchos: Rausch entails an

eccentricity, leaving the sphere of that which we could, along with

Schopenhauer, call the “principium individuationis”—the ability to

differentiate, accompanied by its embodiments of representation (Nietzsche

1999a, 120–122), whereupon things are, as it were, in their place; trees are

trees, houses are houses and people are subjects who make their decisions

autonomously and in the capacity of their own responsibility. By contrast, the

Rausch reveals the erupting force “of the general element in nature” (Nietzsche

1999a, 120). Going far beyond Schopenhauer—who nevertheless granted music a special

status inasmuch as it does not depict or represent anything but rather

manifests the “will” itself—Nietzsche accounts for the experience of the

Dionysian with the experience of chaos, in which distinctions no longer hold

any validity whatsoever and things blur together indiscriminately. It is for

that reason that Nietzsche, in examining the Dionysian, speaks of the

“‘barbaric’” (Nietzsche 1999a, 27), the “horror” (Nietzsche 1999a, 17) and

“terror” or “shock” (Nietzsche 1999a, 21), whereby it can be added that

“shock”—as Plato put it, that “freefall into the darkness”—belongs as much as

the Aristotelian “self-astonishment” does to the “primeordial” philosophical

feelings, that is to say, to those emotions that first teach us to

philosophize. What does this astonishment, this shock effectuate? Certainly,

the latter can be tied to the experience of the sublime à la the traditional

schools of pseudo-Longinus and Edmund Burke— but first, at the onset, this

shock creates a rupture, a shift, a catastrophë. Nietzsche, too, speaks of the

“tearing apart” (Zerreissung) (Nietzsche 1999a, 20), a dis-rupture of all ties

and points of reference as well as the destruction of the “usual barriers and

limits of existence” (Nietzsche 1999a, 40). The special thing about Nietzsche

is, however, that the “unsettling” nature of this rupture is not the kind to be

avoided at all costs, the destruction of an order prerequisite to life, but is

rather— also assuming the literal meaning of “unsettling” (entsetzlich)—that

which “re-settles” (versetzen) us into another place, through that very process

opening up something “never before perceived.” In short, it is the negativity

of the rupture that first serves as prerequisite of the other, the new. As a

result, what is decisive about the Dionysian is the wholehearted negation

(Nietzsche 1999a, 138), through which—as stated in Nietzsche’s work on the

tragedy—the “principle of sufficient reason […] appears to suffer an exception”

and the human being will, “suddenly become confused and lose faith in the

cognitive forms of the phenomenal world” (wenn er plötzlich an den

Erkenntnisformen der Erscheinung irre wird) (Nietzsche 1999a, 17) but, through

that very fact, stumble near to the “truth” of nature and of “life” (cp.

Nietzsche 1999a, 39): “Apollo stands before me as the transfiguring genius of

the principium individuationis, through whom alone release and redemption

in semblance can truly be attained, whereas under the mystical, jubilant shout

of Dionysos the spell of individuation is broken, and the path to the Mothers

of Being, to the innermost core of things, is laid open” (Nietzsche 1999a, 76).

One

must slightly mitigate the pathos of the formulation in order to reach the core

of what is meant; for if Apollo represents the language of form—whose

traditional principle is identity, whose Romantic criticism is the fragment,

whose irresolvability nevertheless holds to its basic tenet because the seal of

“measure” (Nietzsche 1999a, 27) applies even in those places where only the

frail appears (erscheint)—then Dionysus signifies the language of

differentiation, grounded in negation and only allowing itself to be spelled

out in the negative. It is for that reason that a note from Nietzsche’s

unpublished writings dating to 1885 combines the divinity with diabolos (cf.

Nietzsche, 1999b, KSA 11, 473); the word here, used in the singular, is not

meant to denote seduction—the diabolical as negative principle par

excellence—but rather should be read in light of the ancient contradistinction

between symbolon and diabolon, “throwing together” (Ger.: Zusammenwerfen) and

“throwing into disarray”9 (Ger.: Durcheinanderwerfen)—order and chaos as the

corresponding moments of interplay in a game (Spiel).

The

negativity of the Dionysian makes a decided appearance (Erscheinen) here as

indispensable moment of creativity. Nietzsche conceives of the creative much

less as emerging from creatio than from the Riss (“fissure”) or

differentiation. For this reason, I speak of the transition of an aesthetic of

representation or of form to an “aesthetic of difference,” as is characteristic

of the avant-garde throughout the transition from the art of the classical to

modernity, particularly at the beginning of the 20th century. One could say

that Nietzsche, within the emphatic language of the 19th century, premonished

the avant-garde. Moreover, this dramatically points to an elementary

“experience of difference” that also allows itself to be expounded as the

Aufscheinen (“dawning appearance”) of “ex-istence;” (cf. Lyotard 1994 and Mersch

2004) and that drama rests in its definitions of a higher truth, a higher truth

itself later revealed to be an illusion just as it is heralded with fanfare and

as it indicates a further dichotomy tracing a path throughout Nietzsche’s

work—namely, the polarity of “reflection” and “true knowledge” (Nietzsche

1999a, 40), or analysis, method and determination on the one hand and

revelation on the other. Put differently, the Dionysian means the very moment

of that Riss so literally tantamount to the Aufriss10 of presence—that

primordial tremor, to quote Heidegger, “that there are beings, rather than not”

(cp. e.g. Heidegger 1994, 3).

Nietzsche both attempted to capture and mystified this extraordinary moment in ever-new turns of phrase and formulations. I quote: “The Olympian magic mountain (Zauberberg) now opens up, as it were, and shows us its roots” (Nietzsche 1999a, 23). At the same time, he speaks of the “salvation” (Erlösung) into or within the “mystical sense of oneness” (Nietzsche 1999a, 19), of the “truly existing (Wahrhaft-Seiende) and primal unity (Ur-Eine)” and the gaze into “the true essence of things” (Nietzsche 1999a, 40), which the “ecstatic vision” of rapture necessitates (Nietzsche 1999a, 26). Nietzsche himself appears to be literally hingerissen (“enraptured”) and mitgerissen (“swept away”) by his formulations, but even in the medium of language itself we find ourselves dealing with a delirium, a futility, one that seeks less to evoke the disparity between forces or between aesthetics of form and of event than it does to demonstrate a historical disparity—the dichotomy between the legacy of tradition and that which is expressible, future, that which presages something only later to be taken up by the avant-garde of modernity: an ongoing practice of the “destructive” or “deconstruction,” which presupposes the positives of the form, the medium and the representation, and therefore the elements of the classical aesthetic, in order to break with them and to chronicle within them the difference (Differenzpunkt) of their dissolution. At the same time, two dichotomous forms of knowledge are allocated to them. The first is the law of selflimitation and self-knowledge, which conceptualizes the artist as author and subject of his work, which bring to expression his/her intentio, his/her inspirations and his/her will. The second is the experience of a scar, an injury incurred upon time and its literal unheilen,11 a scar stylizing the artist as an anomaly, stigmatized and rejected—a scar that, as it is furnished with the insignia of its victim and his madness, is nonetheless, according to the auto-descriptions of Arthur Rimbaud, Lautréamont and also Antonin Artaud, able to articulate by name a higher “truth.” If Nietzsche—at least at the point in time at which he composed The Birth of Tragedy—appears caught within the radicalization of the late Romantic and continual formulation of its internal prolongations, it is my thesis that a deeper dichotomy is already rooted in the confrontation between the Apollonian and Dionysian, one that “ex-hibits” the breaking of the new epoch, its inescapable caesura that will simultaneously transport artistic practice into new terrain. Nietzsche only suggests this possibility without further explication. His reference to the Dionysian power of negation thus eases up the extreme Romantic fixation on the subject of the artist and his/her extraordinary genius, something Nietzsche himself doubtless always idealized; at the same time, however, he discards the “previous” expressive media in order to unleash that which has no endemic representation and does not tolerate symbolization—for the Other, the extraordinary, the not-yet-conceived, only “exists” in the sense of a giving, a gifting, where the language, the picture and, along with that, the forms of representation are destroyed, where the “difference” thus cleaves the medial in order to uncover in and through it a heterogeneity, an entity as invisible as it is unable to be represented.

Nietzsche both attempted to capture and mystified this extraordinary moment in ever-new turns of phrase and formulations. I quote: “The Olympian magic mountain (Zauberberg) now opens up, as it were, and shows us its roots” (Nietzsche 1999a, 23). At the same time, he speaks of the “salvation” (Erlösung) into or within the “mystical sense of oneness” (Nietzsche 1999a, 19), of the “truly existing (Wahrhaft-Seiende) and primal unity (Ur-Eine)” and the gaze into “the true essence of things” (Nietzsche 1999a, 40), which the “ecstatic vision” of rapture necessitates (Nietzsche 1999a, 26). Nietzsche himself appears to be literally hingerissen (“enraptured”) and mitgerissen (“swept away”) by his formulations, but even in the medium of language itself we find ourselves dealing with a delirium, a futility, one that seeks less to evoke the disparity between forces or between aesthetics of form and of event than it does to demonstrate a historical disparity—the dichotomy between the legacy of tradition and that which is expressible, future, that which presages something only later to be taken up by the avant-garde of modernity: an ongoing practice of the “destructive” or “deconstruction,” which presupposes the positives of the form, the medium and the representation, and therefore the elements of the classical aesthetic, in order to break with them and to chronicle within them the difference (Differenzpunkt) of their dissolution. At the same time, two dichotomous forms of knowledge are allocated to them. The first is the law of selflimitation and self-knowledge, which conceptualizes the artist as author and subject of his work, which bring to expression his/her intentio, his/her inspirations and his/her will. The second is the experience of a scar, an injury incurred upon time and its literal unheilen,11 a scar stylizing the artist as an anomaly, stigmatized and rejected—a scar that, as it is furnished with the insignia of its victim and his madness, is nonetheless, according to the auto-descriptions of Arthur Rimbaud, Lautréamont and also Antonin Artaud, able to articulate by name a higher “truth.” If Nietzsche—at least at the point in time at which he composed The Birth of Tragedy—appears caught within the radicalization of the late Romantic and continual formulation of its internal prolongations, it is my thesis that a deeper dichotomy is already rooted in the confrontation between the Apollonian and Dionysian, one that “ex-hibits” the breaking of the new epoch, its inescapable caesura that will simultaneously transport artistic practice into new terrain. Nietzsche only suggests this possibility without further explication. His reference to the Dionysian power of negation thus eases up the extreme Romantic fixation on the subject of the artist and his/her extraordinary genius, something Nietzsche himself doubtless always idealized; at the same time, however, he discards the “previous” expressive media in order to unleash that which has no endemic representation and does not tolerate symbolization—for the Other, the extraordinary, the not-yet-conceived, only “exists” in the sense of a giving, a gifting, where the language, the picture and, along with that, the forms of representation are destroyed, where the “difference” thus cleaves the medial in order to uncover in and through it a heterogeneity, an entity as invisible as it is unable to be represented.

The

distinction thus made virulent correspondingly straddles on the one hand the

Schein and the Erscheinung in terms of the significance of the “what,” which

draws its execution and determination from its individuation, and on the other

the “Erscheinung of the Erscheinung” in the sense of the “which” (quod), that

eventfulness of a presence which never “makes its appearance” (erscheinen) in

the positive but rather can only be grasped in the negative (cp. Mersch 2002,

355ff.).12 This also means that as long as art is working with form,

representation or technē, it remains media-bound and proceeds as Apollonian;

but as soon as these are dethroned and traversed by art, that which lacks

conceptualization and fails in purpose is allowed to emerge. This, and none

other, is the meaning of the Dionysian: The medium constitutes, shapes and

makes sensory; its fracture or breaking, on the other hand, confronts with a

gap, a Durchriss (“a rupture, having been torn through”), whereby the

“unfitting”—unfitting in the sense of something stepping “outside itself”—

reveals itself. We are then dealing with “another” present time, not one whose

presence is already hidden in its Zeichen (“sign”) or Auszeichnung

(“distinction; sketching or characterization”), its framing or staging, one

which Jacques Derrida designated as “deferred action” and the unavoidable

a-presence (Derrida 1978, esp. 310–311), but rather one in which the experience

of the negative and of alterity intersect, one which only exists where a

contradiction, an aporia occurs. It is for that reason that Nietzsche speaks of

the “detonation” of the principium individuationis as well as—in easily

misunderstood adherence to terminology from the philosophy of subjectivity—of

the “grow in intensity, [which] cause[s] subjectivity to vanish to the point of

complete self-forgetting (Steigerung des Subjectiven zu völliger

Selbstvergessenheit)” (Nietzsche 1999a, 17), the “being-drivenoutside-oneself”

state of “ecstasy” (Nietzsche 2009, 10), as he later describes it, which can

only appear beyond the medial while still existing through media, undermining

and subverting its mediality; the aesthetic of difference supposes the

aesthetic of form in the same measure as it shatters it. Hence, we can only

speak of an “grow in intensity, [which] cause[s] subjectivity to vanish to the

point of complete self-forgetting” where the subjectivity of the subject as

well as the mediality of the medium are as equally salvaged as they are shaken

and transcended. The transition from the aesthetic of form to that which I call

the aesthetic of difference thus implies the desubjectification of creativity;

“subjectivity disappears entirely before the erupting force of the general

element in human life (Generell-Menschlichen), indeed of the general element in

nature (Allgemein-Natürlichen)” (Nietzsche 1999a, 120). As stated in The

Dionysian Vision of the World, “The artistic force of nature, not that of an

individual artist, reveals itself here” (Nietzsche 1999a, 121). With that,

Nietzsche anticipates with equal intensity that dictum of the “death of the author,”

which only later came to actuation via the theories of poststructuralism and

intertextuality. At the same time, however, he holds to a systematic ambiguity

or indeterminacy, because overcoming and being “sanctified” (geheiligt) are

possible for the subject only on the basis of the subjectivity of “life” and

for the artist only within the disempowerment of the Rausch. It is in the

Dionysian principle, thus, that a foreshadowing becomes apparent and, even as

the time and its expressive possibilities are not yet ripe for such an

emergence, we see Nietzsche steering his thoughts toward that end. The question

arises as to what can serve as a replacement where the subject is missing—and,

equally, what art and the artistic process can mean in those places where the

medial has tumbled right through its fracture, its Riss.

With

that, Nietzsche is aiming at every turn for something threatening in the

selfsame moment to slip out of control; only the radicalization to come later

will resolve the ambiguities between the Apollonian and the Dionysian as

artistic forms and aesthetic principles. “[I] was […] the first to understand

the marvelous phenomenon of the Dionysian,” he writes in Ecce homo (Nietzsche

2007, 46); it was he who, in utter furtiveness and solitude, presented a

“victim” in his debut work. “I found no one who understood what I was doing

then,” he adds in Beyond Good and Evil (Nietzsche 1998a, 176). Nietzsche

himself thus discarded The Birth of Tragedy as “Romantic”—not only in the

“SelfCritique” he appended to it later, which particularly castigates

“linguistic kitsch,” but also, more importantly, in his notes between 1885 and

1886 under the heading “Regarding ‘The Birth of Tragedy,’” where we find the

following remark: “A book […] with a metaphysics of the artiste in the

back-ground. At the same time the confession of a Romantic” (Nietzsche 2003,

80). It sought to pin down the Erlösung of illusion and Schein as the classic

goals of art through the force of becoming, whereby the “anihiliation of even the

most beautiful illusion (schönen Schein)” signifies the peak of “Dionysian

happiness” (Nietzsche 2003, 82). A commensurate dichotomy is constructed here

between classical and Romantic art on the one hand and Dionysian (Nietzsche

2003, 80–83) on the other, the latter endowed with the flora of a practice as

destructive as it is life-giving, as equally creative as it is destructive, one

which leaves behind the conventional aesthetic of form and representation. What

is to take its place? Just what is the meaning of “aesthetic of difference”?

I will

make a cautious attempt at accessing this. Nietzsche first removes the artist

from the art and thus thinks his way toward an understanding of art requiring

as little of the self-sufficient “intention to form”—the principle of all art

until the Romantic—as it does of the anticipatory inspiration. “The work of art

where it appears without an artist, e.g., as body […],” reads a fragment from

Nietzsche’s unpublished writings, “[h]ow far the artist is only a preliminary stage.

What does ‘subject’ mean— ?” (Nietzsche 2003, 82) Both purposes belong

together: the Dionysian as the negative—and the Dionysian as

desubjectification, as withdrawal of self-sufficiency. The notations cited

above are made around the same time that the Rausch reaches its emphatic peak

as aesthetic principle in Twilight of the Idols. If Nietzsche still spoke in

the Dionysian Vision of the World of the “Spiel with the Rausch,” for example,

he says from now on, “[f]or there to be art, for there to be any kind of

aesthetic doing and seeing, one physiological precondition is indispensible:

intoxication (Rausch)” (Nietzsche 1998b, 46–48). And what he sees as the most

important thing about the Rausch is the delimitation, the negation of the will,

which on the flip side corresponds to an “feeling of increased power

(Kraftsteigerung)” (Nietzsche 1998b, 47); one could add that “force” here is

used in the sense of an “overabundance of life.” Accordingly, Nietzsche’s

entire later philosophical body of work characterizes itself via extension of

the Dionysian principle; Heidegger tied into this in his interpretation of

Nietzsche, construing the “fill” and “feeling of increased power” as the “will

to power,” and art as its “distinctive form” (Heidegger 1991, 92), one that

designates the exact “opposite” of Kant’s “disinterested pleasure”—in two ways,

in fact: once in view of the aesthetic judgment that binds the experience of

art to receptivity, and once in view of the passivity of the perception and the

“release” (Freigabe) of that “which is” (Heidegger 1991, 109). The first, thus,

is desubjectification, or better, disempowerment of the subject; the second,

its correlate, is the centering of the aesthetic on the body. The a priori of

the lived-body (Leibapriori) does not mean that precedence is assumed by

intensity, surplus, or that which Nietzsche again and again accounts for with

the expression “force” (Kraft) but, rather, that “eccentricity” of a

positionality outside one’s self, which Heidegger, in turn, connects with a

“being embodied” (Leiben) of a “body” (Leib) (Heidegger 1991, 99). One could

say the body here induces a productivity from affect, an unintentional dynamic

touching on the phatic autonomy of an “obsession,” that is to say, on the

passivity of alterity (Mersch 2006).

Thus—as

Heidegger also emphasizes—Nietzsche asks not about the work as a result, as

place of reception, but rather, primarily, about procedures and their

implementation, their impact, about that which is not an intention and its

embodiment but instead signifies an aesthetic thinking in and through deed, as

it were—thinking not set in dichotomous opposition to action and interrupting

it but rather springing from it as its own form of recognition, a knowledge

that is non-discursive and unable to be made discursive. Thirdly—in the literal

sense of meta hodos (following a path), or perhaps even better, in the sense of

poros (a passage always traversing the material and bodily) or of metaporos or

even diaporos (which demands permeability)—a vital method for this, besides

desubjectification and the consummate pathicism seeping through every single

pore (the same word!), is what I have attempted multiple times already to

delineate as a break or interruption, the literally unfathomable depths of a

Riss. This Riss follows from the artistic production just as it passes through

it and comes to pass from it. The correlation Nietzsche draws between art and

event, established upon the aesthetics of production, is based on this

“imposition of difference” (Differenzsetzung). The aesthetic event is the

difference and follows it just as, conversely, the difference proceeds from the

innards of the aesthetic process, as it were, after a Riss has been made within

it. How can this be made comprehensible? With Nietzsche, much remains too

undefined—because, as Heidegger also states in his commentary, for Nietzsche,

“all [is] proper to art. But then art would only be a collective noun and not

the name of an actuality grounded and delineated in itself” (Heidegger 1991,

122). Clearly, the problem rests in the fact that the creative productivity

thus avouched cannot actually be understood; rather, it resembles life, the

presence of the body and its mystification, attributing to it a “will to power”

and thereby arguing no less metaphysically than the artistic concept it is

battling—especially when it comes to the artistic concepts of Plato and Hegel.

Nietzsche, in opposing both, totalizes the fill of life and stylizes its

unfolding as an artistic deed. Contrary to that, the ability to even posit any

given “event of difference” would depend on an appropriate reconstruction of

the particular strategies of artistic production—that is to say, the concrete

underlying figures of difference.

In

closing, allow me to sketch out a few further thoughts. I will use the term

‘aesthetic strategy’ in doing so. This catchword concerns artistic work and the

artistic working method and can— although it does not necessarily exhausted

itself in it—also mean working with the body; if anything, I use it with the

intention of calling to mind the conceptualization of a combination of

practices that play a central role in Adorno’s aesthetic and that initially, at

the very moment of con stellare—that is to say, a scattering or “foreordaining”

(Fügung) of positions (Stellungen)—do nothing other than to reveal their

unfitting mismatch, their gaps or (again quite literally in the German) their

“dislocated faultlines” (lit. Verwerfungen 13 ) and “misrepresentation” (lit.

Entstellungen14). For this, it is necessary to enable the experience of an

‘in-between.’ This “betwixt” happens in the performative by virtue of those

clefts and “chiasms,” which posit an event of difference just as the unfitting

mismatch of those foreordinations (Unfügliche der Fügungen), their self-denial,

and even the force of synthesis are opened up, eased and rent asunder