MOMA AT NGV: MORE THAN 200 WORKS FROM

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK COME TO MELBOURNE

June 9, 2018 – October 7, 2018

MOMA AT

NGV: MORE THAN 200 WORKS FROM

THE

MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK COME TO MELBOURNE

June 9,

2018 – October 7, 2018

May 1, 2018: In an international exclusive, the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV)

presents a major exhibition of modern and contemporary masterworks from New

York’s iconic Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in the world-premiere exhibition MoMA

at NGV: 130 Years of Modern and Contemporary Art, opened June 9, 2018 at NGV

International in Melbourne.

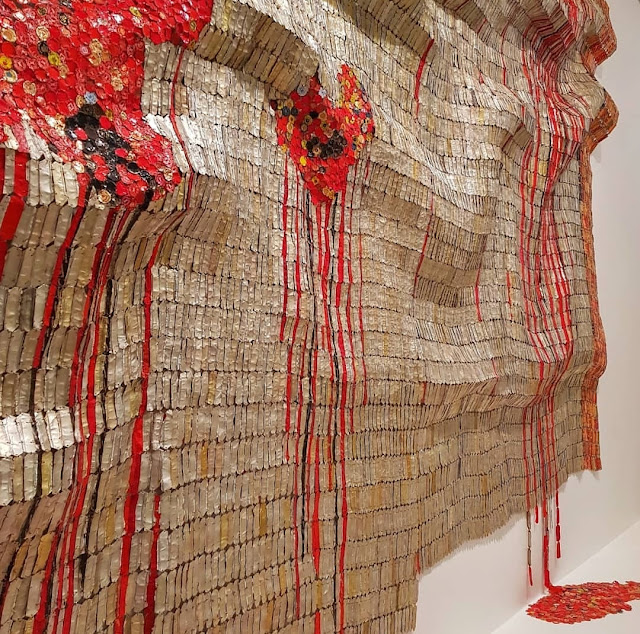

Co-organised

by the NGV and MoMA, the exhibition features more than 200 works – many of

which have never been seen in Australia – from a line-up of seminal nineteenth

and twentieth-century artists, including Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Pablo

Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Edward

Hopper, Louise Bourgeois, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Diane Arbus, Agnes

Martin and Andy Warhol. Bringing the exhibition up to the present are works by

many significant twenty-first century artists including Jeff Koons, Cindy

Sherman, Olafur Eliasson, Andreas Gursky, El Anatsui, Rineke Dijkstra, Kara

Walker, Mona Hatoum and Camille Henrot.

MoMA at

NGV is the largest instalment of the Melbourne Winter Masterpieces exhibition

series to date, for the first time encompassing the entire ground floor of NGV

International. Showcasing MoMA’s multidisciplinary approach to collecting and

the breadth of its collection, the exhibition display features works drawn from

the Museum’s six curatorial departments: Architecture and Design, Drawings and

Prints, Film, Media and Performance Art, Painting and Sculpture, and

Photography.

MoMA at

NGV will explore the emergence and development of major art movements, and

represent more than 130 years of radical artistic innovation. The exhibition

will also reflect the wider technological, social and political developments

that transformed society during this period, from late nineteenth century urban

and industrial transformation, through to the digital and global present. In

recognition of both MoMA and NGV’s long-standing dedication to the study and

presentation of architecture and design, the exhibition explores the

deep-seated connections between twentieth-century art and design practice, with

a particular focus on developments that shaped Europe in the 1920s and ’30s and

the globalised world of the 1960s and ’70s.

Unfolding

across eight loosely chronological thematic sections, the exhibition opens with

‘Arcadia and Metropolis’, examining how artists at the dawn of the 20th century

responded to the rise of cities. ‘The Machinery of the Modern World’ highlights

the simultaneity of foundational avant-garde movements (Futurism, Cubism,

Orphism, Dada) and references MoMA’s 1934 Machine Art exhibition, while ‘A New

Unity’ presents the cross-media manifestations of the Russian avant-garde, de

Stijl, the Bauhaus and Joaquín Torres-Garcia’s School of the South. In ‘Inner

and Outer Worlds’, iconic Surrealist paintings are seen alongside

contemporaneous works that negotiate the relationship between interior and

exterior landscapes. ‘Art as Action’ highlights key examples of Abstract

Expressionism and expands to include other forms of kineticism in the 1950s.

The exhibition’s largest section, ‘Things as They Are’, encompasses the varied

production of the 1960s and ’70s, from Pop art to Minimalism and

Post-Minimalism, followed by ‘Immense Encyclopedia’, focusing on gestures of

appropriation and reflections of identity from the 1980s and ’90s. The last

section of the exhibition, ‘Flight Patterns’, considers contemporary ideas of

movement, migration, and globalisation. Installation and performance works

(Olafur Eliasson’s Ventilator, Simone Forti’s Huddle, and Roman Ondak’s

Measuring the Universe) will also run throughout the course of the

exhibition.

The

Hon. Premier Daniel Andrews said: ‘Picasso, Van Gogh and Matisse: only in

Melbourne will you see this roll call of history’s most iconic art figures – it

will be an experience not to be missed. MoMA is one of the most prestigious

modern art galleries in the world and its partnership with the NGV is testament

to Victoria’s reputation as an international cultural destination.’

Tony

Ellwood, Director, NGV said: ‘This exciting exhibition will showcase an

unparalleled collection of modern and contemporary art and design. We are

delighted to be working with MoMA to bring such an extraordinary and diverse

selection of works to Melbourne. Our visitors will be able to experience

first-hand the momentous change and creativity in the development of modern

art, and consequently appreciate contemporary art and design with greater

understanding.’

Glenn

D. Lowry, Director, MoMA said: ‘MoMA’s mission is to share our story of modern

and contemporary art with the widest possible audience, to encourage the

understanding and enjoyment of the art of our time. We are thrilled to have

this opportunity to share these important works from nearly every area of our

collection with the NGV and the many visitors who will take advantage of this

rare opportunity.’

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/media_release/moma-at-ngv-more-than-200-works-from-the-museum-of-modern-art-new-york-come-to-melbourne-this-winter/

ARCADIA & METROPOLIS

As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth,

artists reacted to the new era’s industrial innovations in various ways. Some

embraced urbanisation and its technologies, making the metropolis the subject

of their work. Others retreated to Arcadian idylls, composing pictorial

sanctuaries of harmony and balance.

Post-Impressionist painters were among those who

continued to create within established academic genres, seen here in a portrait

by Vincent van Gogh, a landscape by Georges Seurat and a still life by Paul

Cézanne. But if these artists’ subjects were traditional, their techniques were

wholly inventive, including sinuous brushstrokes, divisionist dots and

flattening facets employed as methods to reject illusionism. Others mined

non-Western cultures for fresh inspiration; for example, paintings by Paul

Gauguin and Henri Matisse in this gallery look to Tahiti and Japan,

respectively, for their figures and forms.

At the same time, other artists revelled in portraying

the spectacle culture of rapidly growing cities: Eugène Atget’s photographs,

Jules Chéret’s posters, a painting by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and a film by

Auguste and Louis Lumière all capture the media and movement of a newly wired

Paris. The designs of Berlin-based Peter Behrens – industrial objects as well

as the branding conceived to promote them – similarly speak to the electricity

of the age.

ANDRE DERAIN

BATHERS 1907 (PART FROM PAINTING)

ANDRE DERAIN

BATHERS 1907

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 132.1 x 195 cm

Credit: William S. Paley and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Funds

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

HENRI MATISSE FRENCH 1869–1954

La Japonaise: Woman Beside the Water 1905

Oil and Pencil on Canvas

Dimensions: 35.2 x 28.2 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Purchase and

Anonymous Gift, 1983

© Succession H. Matisse / Succession H. Matisse.

Licensed by Copyright Agency, 2018

HENRI MATISSE FRENCH 1869–1954

La Japonaise: Woman Beside the Water 1905 (Detail)

ANDRE DERAIN

FISHING BOATS, COLLIOURE 1905

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 38.2 x 46.3 cm

Credit: The Philip L. Goodwin Collection

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

PETER BEHRENS

AEG. METAL FILAMENT LAMPS

Lithograph

Dimensions: 69.2 x 52.7 cm

Printer: Hollerbaum & Schmidt, Berlin, Germany

Credit: Arthur Drexler Fund

© 2018 Peter Behrens / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York /

VG Bild-Kunst, Germany

ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER GERMAN 1880–1938

STREET, DRESDEN 1908 ( REWORKED 1919, DATED ON PAINTING 1907) (DETAIL)

ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER GERMAN 1880–1938

STREET, DRESDEN 1908 ( REWORKED 1919, DATED ON

PAINTING 1907)

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 150.5 x 200.4 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Purchase, 1951

Digital Image

© The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018

ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER GERMAN 1880–1938

STREET, DRESDEN 1908 ( REWORKED 1919, DATED ON PAINTING 1907) (DETAIL)

PAUL GAUGUIN FRENCH 1848 - 1903

THE MOON & THE EARTH 1893

Oil on Burlap

Dimensions: 114.3 x 62.2 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Lillie P. Bliss

Collection, 1934 Digital Image

© The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018

HENRI MATISSE FRENCH 1869 - 1954

MUSIC ( SKETCH ) 1907

Oil and Charcoal on Canvas

Dimensions: 73.4 x 60.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of

A. Conger Goodyear in Honor of Alfred H. Barr, Jr.,

1962

© Succession H. Matisse / Succession H. Matisse.

Licensed by Copyright Agency, 2018

HENRI MATISSE FRENCH 1869 - 1954

MUSIC ( SKETCH ) 1907 (DETAIL)

EUGENE ATGET

FLEURS C.1896

Gelatin Silver Printing - Out - Paper Print

Dimensions: Approx. 22 x 18 cm

Credit: Abbott-Levy Collection. Partial gift of Shirley C. Burden

HENRI DE TOULOUSE - LAUTREC, FRENCH 1864–1901

LA GOULUE AT THE MOULIN ROUGE 1891–92

Oil on Cardboard

Dimensions: 79.4 x 59.0 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Mrs. David

M. Levy, 1957

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art, New York,

2018

VINCENT VAN GOGH DUTCH 1853 - 1890

PORTRAIT OF JOSEPH ROULIN 1889

VINCENT VAN GOGH DUTCH 1853 - 1890

PORTRAIT OF JOSEPH ROULIN 1889

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 64.4 x 55.2 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Mr. and

Mrs. William A. M. Burden,

Mr. and Mrs. Paul Rosenberg, Nelson A. Rockefeller, Mr. and Mrs. Armand P. Bartos,

Mr. and Mrs. Paul Rosenberg, Nelson A. Rockefeller, Mr. and Mrs. Armand P. Bartos,

The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection, Mr. and Mrs.

Werner E. Josten,

and Loula D. Lasker Bequest (all by exchange), 1989

Digital Image

© The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018

VINCENT VAN GOGH DUTCH 1853 - 1890

PORTRAIT OF JOSEPH ROULIN 1889 (DETAIL)

JULES CHERET

FOLIES – BERGERE, LA LOIE FULLER 1893

Lithograph

Dimensions: 123.2 x 87.6 cm

Publisher: Folies-Bergère, Paris

Printer: Chaix

Credit: Acquired by Exchange

© 2018 Jules Chéret / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

JULES CHERET

THEATER PHONE 1890

Lithograph

Dimensions: 124.2 x 87.4 cm

Printer: Imp. Chaix (Ateliers Chéret), Paris

© 2018 Jules Chéret / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

AUGUSTE LUMIERE FRENCH 1862–1954

LOUIS LUMIERE FRENCH 1864–1948

DANSE SERPENTINE 1897–99 ( STILL )

Digital File, Transferred From Original 16mm

Handcoloured Film,

Silent, 59 Sec © Institut Lumière

EINSTEIN

AND 20TH-CENTURY ART: A ROMANCE OF MANY DIMENSIONS

Linda

Dalrymple Henderson

A

century after Einstein’s annus mirabilis of 1905, much research remains to be

done on the impact of Einstein and Relativity Theory on 20th-century art as a

whole. For the scientist whom Time magazine declared the “Person of the

Century” in December 1999 and whose effect on 21st-century culture is

unquestioned, this situation may seem rather surprising.1 In large part, it is

the result of a misidentification—that of Einstein’s theories with Pablo

Picasso’s Cubism—which began to be made widely in the 1940s and which came to

dominate the question of Relativity’s relationship to modern art. Typical of

this view is painter Philip Courtenay’s essay “Einstein and Art” for the volume

Einstein: The First Hundred Years, published in 1980 to mark the centennial of

the scientist’s birth. “Cubism attempted to incorporate Einstein’s fourth

dimension to gain ‘realism of conception,’” Courtenay asserts, concluding, “how

much modern art was aided by Einstein’s ideas is an open question; that it was

aided is not.”2 As recently as 2004, Mary Acton’s Learning to Look at Modern

Art declared, “two years before Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,

Einstein had published his Theory of Relativity. A central idea in the theory

was that our view of the world cannot be understood in a purely

three-dimensional way because of the existence of the fourth dimension, which

is time.”3

Such

vague associations of Cubism and Relativity, usually on the grounds of

references to the “fourth dimension” in Cubist literature, had first been

promulgated widely in Sigfried Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture of 1941

and were given their fullest exposition in the writings of Paul Laporte in the

late 1940s. For both Giedion and Laporte, connecting modern architecture and

Picasso’s Cubism to Einstein was a means to validate new forms of artistic

expression and to argue for their grounding in culture at large.4 Having

observed this development firsthand, prominent art historian Meyer Schapiro

reacted strongly to these claims, and at the Jerusalem Einstein Centennial

Symposium in 1979, he delivered what Gerald Holton has described as “an

extensive and devastating critique of the frequently proposed relation between

modern physics and modern art.”5

Schapiro’s

specific target was the purported Cubism-Relativity link. Unfortunately, he

never reworked the talk into an essay for the 1982 publication of the

conference proceedings, and thus his arguments reached a larger audience only

in 2000, with the posthumous publication of his book The Unity of Picasso’s

Art.6 In the meantime, other scholarship on this subject had begun to appear,

including my 1983 book The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in

Modern Art. That text pointed up the absence of accessible literature on

Relativity Theory in France in the pre–World War I era and established, on the

contrary, the Cubists’ focus on the spatial “Fourth Dimension” that had been

the subject of intense popular interest in the early decades of the century.7

Instead

of the fourth dimension as time in the four-dimensional spacetime continuum

Minkowski had formulated in 1908 for Relativity Theory, Cubist painters and

theorists were stimulated by the notion of a suprasensible fourth dimension of

space that might hold a reality truer than that of visual perception. An

outgrowth of the mid-19th-century development of n-dimensional geometry, the

spatial fourth dimension had first been popularized widely in E. A. Abbott’s

1884 Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by a Square, a cautionary tale

about refusing to believe that one’s world was merely a section of the next

higher dimensional space. A massive amount of popular writing on the subject

followed, including a 1909 Scientific American essay contest on the question,

“What is the fourth dimension?” with entries received from all over the world.8

Beginning

with the Cubists in pre–World War I Paris, artists in almost every modern movement

engaged the spatial fourth dimension in one way or another during the first

three decades of the century. In both Picasso’s Portrait of Ambroise Vollard

(Fig. 8.1) and French geometer E. Jouffret’s 1903 rendering of a “see-through”

view of a four-dimensional solid, transparent, multiple views of an object as

well as shifting, shaded triangular facets create an ambiguous space that

cannot be read as three dimensional (Fig. 8.2). “I paint objects as I think

them, not as I see them,” Picasso declared, and—along with his engagement with

the art of Cézanne and African sculpture (as well as the science discussed

below)—contemporary interest in a higher dimension of space encouraged his

increasingly conceptual approach to the visible world.9 Cubist theorists Albert

Gleizes and Jean Metzinger drew directly on Henri Poincaré’s ideas on tactile

and motor sensations in his 1902 La Science et l’hypothèse, in which he

asserted that “motor space would have as many dimensions as we have muscles”

and suggested that one might represent a four-dimensional object by combining

multiple perspectives of it.10

Whereas

Schapiro had argued correctly against the Cubism-Relativity myth, his treatment

of “science” in this period solely as Einstein and Relativity led him to argue

against any sort of art-science connection in the early 20th century. In fact,

Picasso and his fellow Cubist Georges Braque—as well as virtually all artists

before the later 1910s—actually were responding to certain ideas in physics.

However, it was the exhilarating discoveries of the 1890s redefining the

layperson’s understanding of matter and space (e.g., X-rays, radioactivity, the

electron, and the Hertzian waves of wireless telegraphy)— and not Relativity

Theory—that excited artists and writers in the first two decades of the new

century.11 In addition, the ether of space and its model of continuity and

interpenetration had been embraced by the general public and were not to be

dislodged easily, even after the popularization of Einstein’s theories in the wake

of the 1919 eclipse expedition that confirmed his prediction of the curvature of

light by the mass of the sun.12 Rather than Relativity Theory, then, Picasso’s

Vollard portrait gives visual form to the contemporary conception of space as

suffused with ether and matter as transparent and continually dematerializing

into the ether on the model of radioactivity. If Gustave Le Bon’s 1905

bestseller L’Evolution de la matière was the primary French popularization of

this view, American science writer Robert Kennedy Duncan captured its essence

in his 1905 book The New Knowledge: “How much we ourselves are matter and how

much ether is, in these days, a very moot question.”13 Marcel Duchamp,

Picasso’s counterpart in the early 20th century, was the artist most fully

engaged with both late Victorian ether physics and the geometrical fourth

dimension—a prowess manifested in his extensive notes for his nine-foot-tall

work on glass, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even of 1915–23

(Fig.8.3).

The

Large Glass, as it is known, is a scientific and mathematical allegory of

frustrated desire rooted in the insuperable contrasts Duchamp created between

the realm of the Bride above and the domain of the Bachelors below. Here

Duchamp’s organic Bride hangs, gravity-free, in an ethereal, indeterminate

space he defined as four-dimensional, forever beyond the reach of the three

dimensional, perspectival gravity-bound Bachelor Machine below.14 The rising

acclaim for Einstein and Relativity Theory after 1919, however, would alter the

terrain for Duchamp and other early 20th-century artists, gradually displacing

the popular spatial fourth dimension and inaugurating the conception of time as

the fourth dimension that would characterize the public’s view for much of the

century. Only in the 1960s and 1970s would the spatial fourth dimension begin

to be recovered in popular literature, and it would re-emerge full-blown only

in the 1980s with the rise of string theory and computer graphics.15

Duchamp,

who died in 1968, lived through this metamorphosis and, as a result, waited

until 1966 to publish his playfully inventive Large Glass notes on

four-dimensional geometry and space in his White Box or A l’infinitif, issued by

the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in early 1967.16

Duchamp

had published facsimiles of others of his notes in two earlier artist’s boxes,

and Einstein’s status as cultural hero by century’s end was made clear in the

deluxe publication of his 1912 manuscript on Special Relativity.Advertised as

“the book of the century,” the manuscript was published with a slipcase and

marketed as if it, too, were a deluxe artist’s book.17 From the 21st century we

can now observe the waxing and waning of the two competing traditions

represented by these individuals and objects: the spatial fourth dimension

engaged by Duchamp and others in the early 20th century versus Einstein and

Relativity Theory.

From

its earliest days, the popular fourth dimension had quickly acquired a variety

of nongeometric associations—from mystical higher consciousness and infinity to

science fiction usages—that made it attractive to a wide range of artists.

Einsteinian Relativity, by contrast, represented a much more specifically

scientific or mathematical source, which was also less immediately suggestive to

the visual imagination of artists. Nonetheless, a good many artists took up the

challenge of addressing Einstein and/or Relativity, and we can begin here to

trace the shape of those responses during the 20th century and even propose an

initial typology of reactions to them. Their varied form reflects, in part, the

changing attitudes toward and understanding of Einstein and his physics during

the course of the century. With Einstein standing as the single cultural icon

of science for much of this period, any examination of his impact necessarily

ranges beyond painting, sculpture, architecture, and experimental film to

include the broader field of visual representations— cartoons, popular

photographic images, book and magazine covers, and specific scientific

illustrations—that served as vehicles for the art world’s “romance of many

dimensions” with the scientist and his theories.

The

cover of the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung for December 14, 1919 (Fig.

8.4),documents Einstein’s sudden rise to celebrity that year, declaring,“ a new

great in world history: Albert Einstein, whose researches, signifying a

complete revolution in our concepts of nature, are on a par with the insights

of a Copernicus, a Kepler, and a Newton.”

As

might be expected, the first widespread artistic response to Einstein and his

ideas occurred in his home city of Berlin, which during the early 1920s became

a crossroads for the international artistic avant-garde. Soon after this cover

photo appeared, Berlin Dadaist Hannah Höch incorporated it into her monumental

(over a meter tall) photomontage, Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knifethrough the

Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, dated 1919–20 (Fig.8.5).

In her

commentary on postwar Weimar culture, Höch places Einstein in the upper left

quadrant with other signs of revolution—literal and figurative—in opposition to

the German military and Kaiser Wilhelm and in league with the Dadaists at lower

right. Höch’s disjunctive and cacophonous technique of photomontage shouts

Dada’s critique of values held sacred in art and culture—just as Einstein’s

Relativity Theory had undercut the absolutes of Newtonian science.18 No

knowledge of the new physics was necessary for Höch’s message—the face of

Einstein sufficed for her purposes, as it would for a number of artists,

designers, and cartoonists later in the century.

Predating

Höch’s exposure to Einstein, the first major attempt in Germany to embody any

aspect of Relativity physics was actually Erich Mendelsohn’s Einstein Tower

(Fig. 8.6), built in 1920–21, but designed between 1917 and 1920.Mendelsohn was

unique in having a direct connection to Einstein’s theories well before his

1919 emergence as a celebrity—in this case through the astronomer Erwin Finlay

Freundlich. Mendelsohn had met Freundlich in 1913, when he was already in

contact with Einstein about conducting experimental observations to test

General Relativity. Freundlich conceived the Einstein Tower project with this

goal in mind, and as Kathleen James has documented, Mendelsohn’s design was

clearly stimulated by the astronomer’s exposition of Einstein’s theories.19

Seeking to express the new awareness of the energies inherent in mass, the

architect chose reinforced concrete (ultimately replaced with brick in key

places) to create a “dynamic...and rhythmic condition” in architecture.

Mendelsohn was also particularly struck by the discussion in Special Relativity

of the contractions of form that would be observed at the speed of light, and

such deformations of distance and time would subsequently become one of the

visual signs of Relativity Theory.20 Rooted in Jugendstil and Expressionist

architectural styles, the Einstein Tower—like the Italian Futurism to which Mendelsohn

also looked— interpreted science and technology in organic terms. Here his

building surges forward as if its internal energies and formal distortions were

those of muscles of the human body.

Mendelsohn’s

organic vision of Relativity Theory was soon to be replaced by an emphasis on

geometric form in the context of the Berlin avant-garde’s links to Dutch De

Stijl and Russian Constructivism. Not until French Surrealism in the 1930s and

1940s would the organic again become a preferred language for Relativity-oriented

art.Although in the 1940s the Surrealists’ focus would be on imaginative

renderings of the space-time continuum, as discussed below, Salvador Dalí’s

1931 The Persistence of Memory (see Plate 1) engages the distortions of space

and time in Special Relativity that had also struck Mendelsohn. Among the

Surrealists, Dalí was one of the artists most engaged with science, and he drew

on both psychoanalysis and recent developments in science to support his theory

of Paranoic-Critical Activity intended to “contribute to a total discrediting

of the world of reality.”21 Dalí’s interest in Einstein and Special Relativity

is clear in a seminal essay of 1930,in which he compares the paranoic “psychic

dilation of ideas”to Einstein’s “physical dilation of measures.” In The

Persistence of Memory, Dalí, inspired by a plate of melting cheese, gives

visual form to the temporal and spatial distortions in Special Relativity,

producing, as he later described it, “the soft, extravagant, and solitary

paranoic-critical Camembert of time and space.”22

Given

the variety of these three initial images, it is useful to categorize such

responses in order to begin to characterize the ways in which 20thcentury

artists have engaged Einstein and Relativity Theory. Höch’s collage (Fig. 8.5)

is the first of the genre that would dominate visual representations of Einstein

and Relativity—the image of Einstein himself.23 Formal distortion or specific

contraction of forms in the work of artists aware of Einstein such as

Mendelsohn or Dalí—or graphic designers of book covers like David Cassidy’s

1995 Einstein and Our World—would be second on the initial list of eight

approaches this essay will suggest.24 That sign of Relativity, however, has

been rarer than the primary artistic response to Einstein that emerged in the

early 1920s—the incorporation of time into art. As noted earlier, the new

definition of time as the fourth dimension was rooted in Minkowski’s 1908 four

dimensional space-time continuum that provided a framework for the viewpoints

of all observers after Einstein had made them relative in 1905.25 Whereas

Gottfried Ephraim Lessing in the 18th century defined painting as the spatial

art and music as the temporal art, Einstein’s and Minkowski’s theories now

encouraged artists to claim time as their domain as well. This infusion of time

and motion into art, which stands as a third type of response, was by far the

most prevalent among artists throughout the 20th century.

No

other German artist enjoyed Mendelsohn’s front-row seat on developing

Relativity physics during the 1910s.After 1919, however, Einstein’s presence in

Berlin and popular fascination with his theories made the city a locus for

avant-garde innovation in response to the newest science.26 Moreover, because

of the much greater scientific interest in Relativity Theory in Germany and

Russia in the 1910s (in contrast to France, England, and the United States),

German and Russian artists who gathered in Berlin were more likely than others

to have heard something of Relativity Theory before the 1919 eclipse.27 Indeed,

the two major Russian artists who participated in the Berlin milieu, Naum Gabo

and El Lissitzky, had both spent time studying in Germany: Gabo pursued

medicine, science, and art history in Munich, and Lissitzky studied

architectural engineering in Darmstadt before earning a diploma as

“engineer/architect” in Moscow. Gabo later recalled first hearing of Relativity

Theory in 1911 or 1912, when he was taking physics classes in Munich.28 Rather

than physics, though, it was Gabo’s engineering skill that prepared him to

create the first time-based work of art.

While

still in Moscow in 1920, Gabo had produced his Kinetic Construction (Standing

Wave) (Tate Gallery, London), a vertical steel rod mounted on a base containing

an electromagnet and springs that set the rod into the vibratory pattern of a

standing wave.29 When Gabo exhibited the work in Berlin in 1922, he highlighted

the sculpture’s temporal quality with the title Kinetic Construction (Time as a

New Element of Plastic Art).Already in their Realist Manifesto of 1920, Gabo

and his brother Antoine Pevsner had alluded to the newly popular space-time of

Relativity Theory: “Space and time are re-born to us today....The realization

of our perceptions of the world in the forms of space and time is the aim of

our pictorial and plastic art.”30 As the first sculpture in the history of art

to incorporate motorized motion, Gabo’s Kinetic Construction is a milestone in

the development of the tradition of kinetic art that would reach its height in

the 1950s and 1960s. In a 1957 interview, Gabo affirmed his continued commitment

to the temporal fourth dimension: “Constructive sculpture...is four-dimensional

in so far as we are striving to bring the element of time into it.”31

By 1922

the Berlin studio of the Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy had become a

central gathering point for avant-garde artistic discussion. In that year

Moholy conceived the kinetic work he called a Light Prop for an Electric Stage,

which he filmed in 1930 as it produced its moving patterns of reflected light

(Fig.8.7).The Light-Space Modulator, as the work came to be known after his

death in 1946, would become the single most important icon of the “space-time”

world the artist subsequently promoted in his books such as The New Vision

(1928, 1946) and Vision in Motion, first published in 1947 and in print into the

1970s.32 Instrumental in establishing the curriculum at the Bauhaus, Moholy

actually met with Einstein in 1924 to discuss the possibility of his writing a

popular book on Relativity for the Bauhaus buch series.

Although

Einstein did not write the book, he lent his name to the school’s Circle of

Friends.33 For Moholy, Relativity Theory was emblematic of a fundamental

cultural shift toward a more dynamic worldview to which artists must respond by

replacing the static methods of the past with an art of motion and time.

PABLO PICASSO SPANISH 1881 - 1973

THE ARCHITECT’S TABLE 1912

Oil on Canvas on Panel

Dimensions: 72.6 x 59.7 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York The William S.

Paley Collection, 1971

© Succession Picasso / Licensed by Copyright Agency,

2018

The first artists to write extensively about the new

importance of time to art were the Dutch De Stijl artist Theo van Doesburg and

the Russian Constructivist El Lissitzky, who were both drawn to Berlin in this

period. Having heard of the experiments in film by Hans Richter and Viking

Eggeling, van Doesburg visited Berlin in December 1920 and ultimately stayed on

in Berlin and Weimar from 1921 through early 1923.34 In a lecture of 1921 or

1922 entitled The Will to Style, van Doesburg addressed the pioneering experiments

of Eggeling and Richter:

‘’ As a result of the scientific and technical widening

of vision a new and important problem has arisen in painting and sculpture

beside the problem of space, and that is the problem of time. [Noting the need

to incorporate time in painting, sculpture and architecture, he suggests that

the synthesis is already being achieved in film.] Here... new artistic form is

being created from the combining of the impetus of space and time (example: V.

Eggeling and Hans Richter). . . . Using film technique in the painting of pure

form gives the art a new ability: the artistic solution of the dichotomy of

static and dynamic, of spatial and temporal elements, a fitting solution to the

artistic needs of our time.35 ‘’

Eggeling and Richter had been so confident in the

relevance of their new “universal language” of abstract forms in motion that in

1920 they had solicited from Einstein, among others, letters of support for

their application to Universum-Film AG for technical assistance. The film studio

granted their request, although there is no evidence that Einstein wrote such a

letter.36

Van Doesburg, like a number of more established

artists by the 1920s,had actually explored the spatial fourth dimension before

Einstein’s emergence in 1919,and those ideas remained with him as he

contemplated the implications of Relativity Theory for art. After his initial

enthusiasm for Eggeling’s and Richter’s direct incorporation of time in

abstract film, van Doesburg, who died in 1931, spent much of the rest of his

career seeking in his architecture and painting to merge the earlier, spatial

fourth dimension with Relativity Theory’s emphasis on time. His most successful

efforts were in architecture, where drawings such as those in his 1924 Color

Construction in the Fourth Dimension of Space-Time (Fig. 8.8) served

as models for his designs for houses. Van Doesburg argued that architecture

must break out of the traditional “box,” and he compared the space of his new

anticubic architecture to the hypercube of four-dimensional geometry.37 He

further added color to his buildings to emphasize the necessity of movement in

time to viewing the new architecture. Along with Moholy-Nagy, van Doesburg was

an important source for Sigfried Giedion’s theory of modern architecture as the

expression of Einstein’s space-time world in his 1941 Space, Time and

Architecture.38

Before considering the role of time and space-time in

the work of van Doesburg’s fellow visionary Lissitzky, a final aspect of the De

Stijl artist’s film theory reveals a fourth vehicle for artists responding to

Einstein in this period and later: light—either alone or in relation to time

and/or filmmaking. Echoing the argument he had made for an anti cubic

architecture, van Doesburg utilized the four-dimensional hypercube in a 1929

essay on film to suggest that the film projection surface should be broken open

to create a new “light-space continuum.”39 Van Doesburg’s terminology, in fact,

may well have been a source for the later usage of Light-Space Modulator as the

title for Moholy’s Light Prop. Both Moholy’s emphasis on the role of light in

the new space-time world in the New Vision and Giedion’s Space, Time, and

Architecture were critical stimuli in the 1940s for American painter Irene Rice

Pereira. Like van Doesburg, Pereira was grounded in the tradition of the

spatial fourth dimension as well as the new world of Relativity, which she

embraced.40 As she declared in a 1940 lecture,

‘’ In abstract art, space-time is the dominant

concept. . . . [T]he abstract artist seeks, by using contemporary knowledge, to

create new forms to express the new age. Space-time is his medium, and

substances of modern science the material with which he works. In its own

right, abstract art seeks plastic equivalents for the revolutionary discoveries

in mathematics, physics, biochemistry, radio-activity...41 ‘’

In works such as Transversion (Fig.8.9), Pereira

painted on the back of the newest types of corrugated and textured glass (i.e.,

“substances of modern science”) and then mounted these panes in front of

painted panels to incorporate light as energy directly into the work of art.

The exploration of light— “light-space,” as this approach might be termed—was

reaffirmed as appropriate to the “century of Einstein” by sculptor Athena Tacha in

a 1967 article on Sculptured Light. In her text Tacha addresses both static

and kinetic light works by contemporary artists as well as by the pioneers of

the 1920s, including Gabo and Moholy-Nagy, whose description of light as

“time-spatial energy” she notes. Manifesting the continuity between the 1920s

and 1960s in the “century of Einstein,” Tacha concludes,“ Light-art is

intrinsically not just three- but four-dimensional, since time is also an

essential quality of it.”42

Returning to 1920s Berlin, in contrast to van

Doesburg’s initial advocacy of time in film as the appropriate expression of

Relativity Theory, the Russian Lissitzky only espoused time or motion in the

mid-1920s. Before that, in the paintings he termed “Prouns”(an acronym for

“project for affirmation of the new”), Lissitzky, who had been a pupil of the

Suprematist Kazimir Malevich, worked to extend his mentor’s investigations of a

cosmic spatial fourth dimension in relation to Relativity’s new conception of

space-time.43

Referring repeatedly to Einstein, Lissitzky declared

in his 1920 essay “Proun,” “Methods which were once employed in a particular

branch of art, knowledge, science, philosophy, are now being transferred into

other areas. This is happening, for example, to the four coordinates of

Minkovsky’s world: length, breadth, height, and the fourth one, time, are being

freely interchanged.”44 Lissitzky preserved Suprematism’s freedom from

orientation; however, in contrast to Malevich’s planes of color floating freely

in an absolute white space, Lissitzky in Proun 30T (Fig.8.10) figures a

relational space created and curved by the complex forms within it. In many of

his Prouns, the artist also achieved an unprecedented degree of ambiguous

spatial shifting through his use of Necker-reversing, axonometrically projected

three-dimensional forms.45

By the time of his 1924 essay A.[rt] and Pangeometry,

however, Lissistzky had rejected the possibility of effectively figuring

space-time in painting, declaring that “the multi-dimensional spaces existing mathematically

cannot be conceived, cannot be represented, and indeed cannot be materialized.”

Noting that “space and time are different in kind,” he concluded that “time

[itself] now becomes a factor of prime consideration as a new constituent of

plastic F[orm].”46 Lissitzky referred to the Prouns as a “interchange station

between painting and architecture,” and by 1923 he had already begun to move

beyond painting to incorporate time and motion directly into exhibition spaces,

such as his Proun Room of 1923 and subsequent designs.47 Here Lissitzky set his

viewer into motion in an environment of geometric shapes painted or mounted on

walls,creating a new kind of perceptual experience. Declaring his preference

for physical space versus mathematical spaces in A. and Pangeometry, Lissitzky

touted a new, motion-generated “imaginary” space that would produce a

“fundamental change” in the “apparatus of the senses.”48 Yet in 1924 Lissitzky

continued to celebrate non-Euclidean geometry’s “explod[ing] of the absoluteness

of Euclidean space,” as he had done in the 1920 “Proun” text, and the curved

elements present in many of the Prouns strongly suggest General Relativity’s

description of the non-Euclidean curvature of the space-time continuum in the

vicinity of matter.49 Lissitzky made this very point in a 1924 letter to De

Stijl architect J.J.P. Oud, arguing that the straight line “does not correspond

with the universe, where there are only curvatures and no straight lines.”50

Indeed, the non-Euclidean curvature of space-time would become an increasingly

important theme in the subsequent figurations of space-time, particular among

the Surrealists, whose form language itself was already organic and curvilinear.

“Imagining space-time” effectively designates this

fifth approach to Relativity Theory, beginning with Lissitzky and continuing

with the Surrealists in the 1940s (and occasionally in subsequent decades). In

his 1939 essay “Des tendances les plus récentes de la peinture surréaliste,”

reprinted in Le Surréalisme et la peinture in New York in 1945, Surrealism’s

founder André Breton discussed the artists Roberto Matta Echaurren, Gordon

Onslow Ford, and Oscar Dominguez as specifically concerned with the

“four-dimensional universe”of space-time. Of their works such as Matta’s 1944

The Vertigo of Eros (Fig.8.11), Breton explained,

‘’ Though, in their forays into the realm of science,

the accuracy of their pronouncements remain largely unconfirmed, the important

thing is that they all share the same deep yearning to transcend the three-dimensional

universe .Although this particular question provided one of the leitmotifs of

cubism in its heroic period, there is no doubt that it assumed a greatly

heightened significance as a result of Einstein’s introduction into physics of

the space-time continuum. The need for a suggestive presentation of the

four-dimensional universe is particularly evident in the work of Matta

(landscapes with several horizons) and On slow Ford.51 ‘

Note: You may scroll down page to read whole essay under headline of the INNER & OUTER WORLD ....

UMBERTO BOCCIONI ITALIAN 1882 - 1916

UNIQUE FORMS OF CONTINUITY IN SPACE 1913 (CAST 1931)

Bronze

Dimensions: 111.2 x 88.5 x 40.0 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Acquired Through

the Lillie

P. Bliss Bequest (by Exchange), 1948 Digital Image

© The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018

GIACOMO BALLA

SWIFTS: PATHS OF MOVEMENT + DYNAMIC SEQUENCES 1923 (DETAIL)

THE MACHINERY OF THE MODERN WORLD

In the first decades of the twentieth century, multiple artistic movements arose in response to rapid technological advances that were both largely productive, such as the invention of aeroplanes and automobiles, and destructive, including the devastating machines of the First World War.

Pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Cubism compressed multiple perspectives into flat planes, conveying the fractured nature of vision in a newly stimulated society. Robert Delaunay’s and Sonia Delaunay’s resplendently coloured canvases addressed the effects of modernity on the perception of time, expressing the phenomenon of simultaneity, or the possibility of multiple experiences existing at once. Italian Futurists, such as Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla, devoted their compositions to tracing the dynamic trajectories of high-speed motion. And Marcel Duchamp, affiliated with Dada, dared to classify an everyday object as a work of art, introducing the radical concept of the readymade.

Machines also figured in artists’ inventions, whether in imagery or as actual objects. Fernand Léger paid homage to the propeller in his paintings and harnessed the kinetic quality of film to choreograph a mechanical ballet. Photographs by Margaret Bourke-White and Charles Sheeler document the whirring gears and fiery furnaces of manufacturing equipment. The architect Le Corbusier declared houses to be ‘ machines for living in ’, and MoMA’s landmark 1934 exhibition Machine Art put steel objects on pedestals, elevating ball bearings and springs to the status of icons.

GIACOMO BALLA

SWIFTS: PATHS OF MOVEMENT + DYNAMIC SEQUENCES 1923

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 96.8 x 120 cm

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

ROBERT DELAUNEY FRENCH 1885 - 1941

SIMULTANEOUS CONTRASTS: SUN AND MOON 1913, DATED 1912

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 134.5 cm Diameter

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Mrs Simon

Guggenheim Fund,

1954 Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art, New

York, 2018

MARCEL DUCHAMP AMERICAN, BORN FRANCE arcel 1887 - 1968

BICYCLE WHEEL 1951 ( THIRD VERSION, AFTER LOST ORGINAL

OF 1913)

Metal Wheel Mounted on Painted Wood Stool

Dimensions: 129.5 x 63.5 x 41.9 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York The Sidney and

Harriet Janis Collection, 1967

© Succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris. Licensed

by Copyright Agency, 2018

FERNAND LEGER, FRENCH 1881 - 1955

PROPELLERS 1918

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 80.9 x 65.4 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Katherine S. Dreier

Bequest, 1953

© Fernand Léger / ADAGP, Paris. Licensed by Copyright

Agency, 2018

FERNAND LEGER

BALLET MECANIQUE 1924

35mm Film (Black and White, Silent)

Duration: 12 min.

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

This

film remains one of the most influential experimental works in the history of

cinema. The only film made directly by the artist Fernand Léger, it

demonstrates his concern during this period—shared with many other artists of

the 1920s—with the mechanical world. In Léger's vision, however, this

mechanical universe has a very human face. The objects photographed by Dudley

Murphy, an American photographer and filmmaker, are transformed by the camera

and by the editing rhythms and juxtapositions. In Ball k

on her shoulder, condemned like Sisyphus (but through a cinematic sense of wit)

to climb and reclimb a steep flight of stairs on a Paris street. The dynamic

qualities et méchanique, repetition, movement, and multiple imagery

combine to animate and give an aesthetic raison d'être to

the clockwork structure of everyday life. The visual pleasures of

kitchenware—wire whisks and funnels, copper pots and lids, tinned and fluted

baking pans—are combined with images of a woman carrying a heavy sac of film

and its capacity to express the themes of a kinetic 20th-century reach a

significant level of accomplishement in this early masterpiece of modern art.

Publication

excerpt from Circulating Film Library Catalogue, New

York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1984, p. 167.

SONIA DELAUNAY – TERK FRENCH, BORN UKRAINE 1885–1979

PORTUGUESE MARKET 1915 (DETAIL)

SONIA DELAUNAY – TERK FRENCH, BORN UKRAINE 1885–1979

PORTUGUESE MARKET 1915

Oil and Wax on Canvas

Dimensions: 90.5 x 90.5 cm

Gift of Theodore R. Racoosin, 1955

CHARLES SHEELER

CRISS-CROSSED CONVEYORS, RIVER ROUGE PLANT,

FORD MOTOR COMPANY 1927

Gelatin Silver Print, Printed 1941

Dimensions: 23.9 x 19 cm

Credit: Gift of Lincoln Kirstein

© 2018 The Lane Collection

CHARLES SHEELER

FORD PLANT, RIVER ROUGE, BLAST FURNACE &

DUST CATCHER NOVEMBER 1927

DUST CATCHER NOVEMBER 1927

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 24.1 x 19.2 cm

Credit: Thomas Walther Collection. Horace W. Goldsmith Fund Through

Robert B. Menschel and Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, by Exchange

© 2018 The Lane Collection

GEORGES BRAQUE FRENCH 1882 - 1963

SODA 1912

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 36.2 cm diameter

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Acquired Through

the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange), 1942

© Georges Braque / ADAGP, Paris. Licensed by Copyright

Agency, 2018

MARGARET BOURKE - WHITE, AMERICAN 1904 - 1971

BRAZILIAN CLIPPER C. 1930

Gelatin Silver Photograph

Dimensions: 33.7 x 23.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of the

Photographer, 1974

© Margaret Bourke-White Estate

GEORGES BRAQUE FRENCH 1882 - 1963

SODA 1912 (DETAIL)

LOUISE BOURGEOIS AMERICAN, BORN FRANCE 1911 - 2010

QUARANTANIA, III 1949–50 (CAST 2001)

Bronze

Dimensions: 148.0 x 32.4 x 5.1 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of the Artist,

2002

© The Easton Foundation / VAGA. Licensed by Copyright

Agency, 2018

ELLSWORTH KELLY

RUNNING WHITE 1959

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 223.6 x 172.2 cm

© 2018 Ellsworth Kelly

ART AS ACTION

If in preceding decades Surrealism and its affinities

represented an art of introspection, the 1950s was an era of action. The

discourse of the decade came to be dominated by the large gestures, canvases

and personalities of a group of American painters alternately referred to as

the Abstract Expressionists or the New York School.

Within this reigning approach, also dubbed Action

Painting by the critic Harold Rosenberg, painters developed signature gestures,

from Jackson Pollock’s vigorous drips to Franz Kline’s sweeping, muscular

slashes. Other painters within the group imbued their vast canvases with more

spiritual concerns: Mark Rothko sought to communicate ‘basic human emotions’

through his compositions’ vibrating, multi-hued rectangles; Barnett Newman

aimed to express the sublime through vertical ‘zips’ of colour; and Ad

Reinhardt strove for the absolute in his monochromes.

The kineticism characteristic of art of this period

was not exclusive to painting. Fuelled by currents of air, Alexander Calder’s

mobiles captured nature’s dynamism, and Louise Bourgeois’s sculptures cut like

sharp knives into their surrounding space. Nor was this vitality limited to a

single geography: in Brazil, Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica pioneered a

Neo-Concrete art, which not only foregrounded the action of the artist, but

also prompted participation from the viewer.

MARK ROTHKO AMERICAN, BORN RUSSIA (NOW LATVIA ) 1903 -

1970

NO. 3/NO. 13 1949

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 216.5 x 164.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Bequest of Mrs.

Mark Rothko Through

The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1981

© Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko /

ARS. Licensed by Copyright Agency, 2018

MARK ROTHKO AMERICAN, BORN RUSSIA (NOW LATVIA ) 1903 - 1970

NO. 3/NO. 13 1949 (DETAIL)

FRANZ KLINE AMERICAN 1910 - 1962

WHITE FORMS 1955

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 188.9 x 127.6 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Philip

Johnson, 1977

© Franz Kline / ARS, New York. Licensed Copyright

Agency, 2018

FRANZ KLINE AMERICAN 1910 - 1962

WHITE FORMS 1955 (DETAIL)

JACKSON POLLOCK AMERICAN 1912 - 1956

NUMBER 7, 1950 1950

Oil, Enamel, and Aluminium Paint on Canvas

Dimensions: 58.5 x 268.6 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Sylvia

Slifka in

Honor of William Rubin, 1993

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation / ARS. Licensed by

Copyright Agency, 2018

JACKSON POLLOCK AMERICAN 1912 - 1956

NUMBER 7, 1950 1950 (DETAIL)

BARNETT NEWMAN

ONEMENT III - 1949

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 182.5 x 84.9 cm

Credit: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Slifka

© 2018 Barnett Newman Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New

York

BARNETT NEWMAN

ONEMENT III - 1949 (DETAIL)

HELIO OITICICA

METAESQUEMA 1958

Gouache on board

Dimensions: 50.5 x 68 cm

Credit: Purchased with funds given by Patricia Phelps de

Cisneros in honor of Paulo Herkenhoff

© 2018 Projeto Hélio Oiticica

HELIO OITICICA

METAESQUEMA NO:348 - 1958 (DETAIL)

HELIO OITICICA

METAESQUEMA NO:348 - 1958

Gouache on Board

Dimensions: 46 x 58 cm

Credit: Purchased with funds given by Maria de Lourdes Egydio Villela

© 2018 Projeto Hélio Oiticica

A NEW UNITY

In the 1920s and 1930s, several international art

movements arose that held a utopian view of art’s potential to communicate

universally. Artists reduced forms to their essentials, eliminating decorative

elements to create widely accessible forms of abstraction.

In the years preceding and following the 1917 Russian

Revolution, artists of that country’s avant-garde sought new languages to

express a new society’s ideals. Lyubov’ Popova and Aleksandr Rodchenko were

among those who developed Constructivism, which cast the artist as an engineer

and emphasised the material reality of his or her productions, while Kazimir

Malevich’s Suprematism aimed to transcend the object in pursuit of ‘pure

artistic feeling’. In the Netherlands, Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg

adopted a fundamental language of squares and rectangles, vertical and

horizontal lines and a palette of primary colours plus black and white to

pioneer a movement known as De Stijl (The Style). And in Uruguay, Joaquín

Torres-García created his own Constructivist ‘School of the South’.

These artists’ remarkable synthesis of mediums

abolished distinctions between the fine and applied arts. The achievements of

the Russian avant-garde included posters, theatre designs and films, and

furniture and design objects were crucial manifestations of De Stijl. But it

was perhaps the Bauhaus, the pioneering school that made its home in three

German cities between 1919 and 1933, which offered the era’s ultimate expression

of interdisciplinary practice: from László

Moholy-Nagy’s painting and sculpture, to Gunta Stölzl’s weaving, to Marcel

Breuer’s furniture, and beyond

THEODORE LUX FEININGER, GERMAN 1910 - 2011

BAUHAUS BALCONIES C. 1928

Gelatin Silver Photograph

Dimensions: 23.5 x 17.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Philip

Johnson, 1967

© Estate of T. Lux Feininger

THEO VAN DOESBURG

PRELIMINARY COLOR SCHEME FOR CEILING& SHORT WALLS OF

DANCE HALL IN CAFÉ AUBETTE, STRASBOURG, FRANCE 1926 - 1928 (DETAIL)

DANCE HALL IN CAFÉ AUBETTE, STRASBOURG, FRANCE 1926 - 1928 (DETAIL)

THEO VAN DOESBURG

(CHRISTIAN EMIL MARIE KUPPER) PRELIMINARY COLOR SCHEME

FOR CEILING & SHORT WALLS OF DANCE HALL IN CAFÉ AUBETTE, STRASBOURG, FRANCE

1926-1928

Ink and Gouache on Paper

Dimensions: 27.3 x 62.9 cm

Credit: Gift of Lily Auchincloss, Celeste Bartos, and Marshall Cogan

THEO VAN DOESBURG

PRELIMINARY COLOR SCHEME FOR CEILING& SHORT WALLS OF

DANCE HALL IN CAFÉ AUBETTE, STRASBOURG, FRANCE 1926 - 1928

DANCE HALL IN CAFÉ AUBETTE, STRASBOURG, FRANCE 1926 - 1928

Ink and Gouache on Paper

Dimensions: 27.3 x 62.9 cm

Credit: Gift of Lily Auchincloss, Celeste Bartos, and Marshall Cogan

Department: Architecture and Design

ALEXANDRA EXTER

FAUST FROM ALEXANDRA EXTER: STAGE SETS 1927

One From an Album of 15 Pochoirs

Dimensions: 33 x 50.5 cm

Publisher: Éditions des Quatre Chemins, Paris

Credit: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Nikita Lobanov

ALEXANDRE EXTER, RUSSIAN 1882 - 1949

PROJECT REVIEW (REVUE PROJET) 1927 FROM ALEXANDRE

EXTER:

STAGE SETS (ALEXANDRA EXTER: DECORS DE THEATRE )

1930

Pochoir Print

Dimensions: 33.0 x 50.2 cm

Publisher: Éditions des Quatre Chemins, Paris

The Museum of Modern Art,

New York Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Nikita Lobanov, 1972

Digital Image

© The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018

ALEXANDRA EXTER

DON JUAN & DEATH FROM ALEXANDRA EXTER:

STAGE SETS

1926 (PART)

One From an Album of 15 Pochoirs

Dimensions: 33 x 50.2 cm

Publisher: Éditions des Quatre Chemins, Paris

Credit: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Nikita Lobanov

ALEXANDRA EXTER

SPANISH PANTOMIME FROM ALEXANDRA EXTER: STAGE SETS 1926

One From an Album of 15 pochoirs

Dimensions: 33 x 50.8 cm

Publisher: Éditions des Quatre Chemins, Paris

Credit: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Nikita Lobanov

ALEXANDRA EXTER

DON JUAN, HELL FROM ALEXANDRA EXTER: STAGE SETS 1929

One From an Album of 15 Pochoirs

Dimensions: 33 x 50.2 cm

Publisher: Éditions des Quatre Chemins, Paris

Credit: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Nikita Lobanov

VLADIMIR STENBERG, GEORGII STENBERG

POUNDED CUTLET ( POSTER FOR 1921 FILM AT THE RINGSIDE,

DIRECTED BY CHARLES CHASE, STARRING SNUB POLLARD ) 1927

Lithograph

Dimensions: 105 x 70 cm

Credit: Gift of The Lauder Foundation, Leonard and Evelyn Lauder Fund

VLADIMIR STENBERG, GEORGII STENBERG

THE THREE MILLION CASE 1927

Lithograph

Dimensions: 71.5 x 107.5 cm

Credit: Given anonymously

PIET MONDRIAN, DUTCH 1872 - 1944

Composition in Red, Blue, and Yellow 1937 - 1942

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 60.3 x 55.4 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York The Sidney and

Harriet Janis Collection, 1967 Digital Image

© The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018

GERRIT RIETVELD, DUTCH 1888 - 1964

RED BLUE CHAIR DESIGNED C. 1918,

PAINTED C.1923 Painted Wood

Dimensions: 86.7 x 66.0 x 83.8 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Philip

Johnson, 1953

© Gerrit Thomas Rietveld / Pictoright. Licensed by

Copyright Agency, 2018

LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY 1925

ZII

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 95.4 x 75.1 cm

Credit: Gift of Mrs. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In this

work, made while he was teaching at the Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy explored the

intersection of abstract elements in abstract space. Broken forms, in varying

degrees of transparency, slide past each other on illusory spatial planes,

illustrating the artist's longtime interest in the function and effects of

light. In these years Moholy-Nagy also experimented with photography—a medium

closely aligned with the credo of the Bauhaus: "Art and Technology: A New

Unity." These photographic investigations informed his painting process,

which he reimagined as an art not of pigment but of light. This kind of

cross-medium exploration was strongly encouraged at the Bauhaus, where a broad

range of workshops in the fine and applied arts helped to shape productive

relationships among faculty and students working in diverse media.

KAZIMIR MALEVICH

SUPREMATIST ELEMENTS: SQUARES 1923

Pencil on Paper

Dimensions: 50.2 x 36.2 cm

Credit: 1935 Acquisition Confirmed in 1999 by Agreement With the

Estate of Kazimir Malevich and Made Possible with Funds From the

Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest (by Exchange)

JOSEF ALBERS

BAUHAUS STENCIL LETTERING SYSTEM 1926-1928

Manufacturer: Mettalglas A.G.

Milk Glass and Painted Wood

Dimensions: 61.3 x 60.6 cm

© 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation /

Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York

THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF VICTORIA MELBOURNE

THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF VICTORIA MELBOURNE

The National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) is the oldest

and most visited public art museum in Australia. Established in 1861, the NGV

has two buildings displaying the NGV Collection – NGV International on St Kilda

Road and The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia at Federation Square. NGV

International houses the Gallery’s collections of International art and The Ian

Potter Centre: NGV Australia is home to the Australian art collection –

including works by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island communities. The NGV

Collection includes over 70,000 art works from many centuries and cultures. The

NGV offers an extraordinary visual arts experience with diverse temporary

exhibitions, Collection displays, talks, tours, programs for kids, films,

late-night openings and performances. In 2017, over 3 million people visited

the National Gallery of Victoria.

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/

THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF VICTORIA MELBOURNE' DIRECTOR TONY ELLWOOD

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART' DIRECTOR GLENN LOWRY

THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF VICTORIA MELBOURNE

THINGS AS THEY ARE

In 1963 the art historian Peter Selz criticised the

newly emergent Pop artists for their ‘passive acceptance of things as they

are’. Despite Selz’s negative tone, his phrase captures something in common

among a diverse group of artistic currents that arose in the 1960s and 1970s:

from Pop art, with its unabashed celebration of consumer objects; to

Minimalism, with its matter-of-fact repetition of elemental forms; to

Post-Minimalism, with its emphasis on how materials respond to processes and

exist in space.

As the name implies, Pop artists drew heavily on

popular culture of the age, such as the new musical soundscape fuelled by the

game-changing Fender Stratocaster guitar and disseminated on vinyl records with

iconic cover designs. Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings co-opted the subject and

style of mass-produced comics, while John Chamberlain and Kenneth Anger paid

tribute to the ascendant American cult of the automobile in sculpture and film,

respectively.

Working in a language of reduced geometry and a

limited palette, artists such as Agnes Martin and Sol LeWitt explored the

infinite variations of primary structures in two and three dimensions.

Sculptors including Lynda Benglis and Richard Serra expanded on these

Minimalist foundations, subjecting metal to the effects of gravity in objects

that intervene into the viewer’s experience.

ANDY WARHOL AMERICAN 1928 - 1987

Marilyn Monroe 1967

Screenprint, Edition of 250

Dimensions: 91.5 x 91.5 cm (Image and Sheet)

Publisher: Factory Additions, New York Printer: Aetna

Silkscreen Products, Inc.,

New York The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of

Mr. David Whitney, 1968

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

/ ARS.

Licensed by Copyright Agency, 2018

JOHN BALDESSARI (AMERICAN,

BORN,1931)

WHAT IS PAINTING 1968

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas,

Dimensions: 172.1 x 144.1 cm

ROY LICHTENSTEIN AMERICAN 1923 - 1997

DROWNING GIRL 1963

Oil and Synthetic Polymer Paint on Canvas

Dimensions: 171.6 x 169.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Philip Johnson Fund

(by Exchange) and

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bagley Wright, 1971

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein/Copyright Agency, 2018

CLAES OLDENBURG AMERICAN, BORN SWEDEN 1929

GIANT SOFT FAN 1966 - 1967

Vinyl Filled With Foam Rubber, Wood, Metal and Plastic

Tubing

Dimensions: 305.0 x 149.5 x 157.1 cm (Variable) (Fan),

739.6 cm (Cord and Plug)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York The Sidney and

Harriet Janis Collection, 1967 © Claes Oldenburg

GERHARD RICHTER

DEAD 1963

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 101 x 151.1 cm

Credit: The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection (by exchange)

© 2018 Gerhard Richter

JASPER JOHNS AMERICAN BORN 1930

MAP 1961 (DETAIL)

JASPER JOHNS AMERICAN BORN 1930

MAP 1961

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 198.2 x 314.7 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Mr. and

Mrs. Robert C. Scull, 1963

© Jasper Johns / Gemini G.E.L. / VAGA. Licensed by

Copyright Agency, 2018

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG

SURFACE SERIES FROM CURRENTS 1970

One From a Portfolio of 18 Screenprints

Dimensions: Composition: 89 x 89 cm

Sheet: 101.6 x 101.6 cm

Publisher: Dayton's Gallery 12, Minneapolis, Castelli Graphics, New York

Edition: 100

© 2018 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

JOHN CHAMBERLAIN

TOMAHAWK NOLAN 1965

Welded and Painted Metal Automobile Parts

Dimensions: 111.1 x 132.2 x 92 cm

Credit: Gift of Philip Johnson

© 2018 John Chamberlain / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

SOL LE WITT

CUBIC CONSTRUCTION: DIAGONAL 4,

OPPOSITE CORNERS 1 & 4 UNITS

1971

Painted Wood

Dimensions: 62.2 x 61.6 x 61.6 cm

Credit: The Riklis Collection of McCrory Corporation

© 2018 Sol LeWitt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

ROBERT INDIANA AMERICAN BORN 1928

LOVE 1967

Screenprint, Edition of 250

Dimensions: 86.3 x 86.3 cm (Image and Sheet)

Publisher: Multiples, Inc., New York Printer: Sirocco

Screenprinters, North Haven, Connecticut The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Riva Castleman Fund, 1990

© Morgan Art Foundation / ARS. Licensed by Copyright

Agency, 2018

THINGS AS THEY ARE ( … OR COULD BE )

In the 1960s, disaffection with functionalist

modernism had permeated the fields of architecture and design. The emergence of

a youth consumer market, more informal patterns of socialising and increased

awareness of cultural diversity defied commitment to a single set of attitudes

and beliefs. Openly taking the lead from popular culture and science fiction,

collectives such as Archigram, a radical London-based group of architects,

produced visionary creations that proposed nomadic and flexible alternatives to

traditional ways of living. At the same time, in Italy, Ettore Sottsass

envisaged a futurist technoutopia in which there would be no work and no social

conditioning or sexual inhibition.

Electronics and plastics technologies were hallmarks

of MoMA’s landmark 1972 exhibition Italy: A New Domestic Landscape. On that

occasion, a series of multipurpose living environments, colourful plastic

furniture and innovative lighting, such as the Pillola lamp in the form of a

giant drug capsule, reflected a fresh and playful approach to design. In a sign

of things to come, early video games heralded new forms of leisure, and

computers opened up a language of virtual communication through universally

accepted icons.

TOM WESSELMANN AMERICAN 1931 - 2004

STUDY FOR MOUTH, 8 1966

Synthetic Polymer Paint and Pencil on Paper

Dimensions: 26.2 x 35.2 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York John B. Turner

Fund, 1969

©Tom Wesselmann / VAGA. Licensed by Copyright Agency,

2018

HIPGNOSIS, LONDON (ART DESIGN STUDIO) BRITISH 1968 -

1982

STORM THORGERSON BRITISH 1944 - 2013

AUBREY POWELL BRITISH BORN 1946

ATLANTIC RECORDS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (RECORD LABEL)

AMERICAN EST.

1947

Lithograph

Dimensions: 30.5 x 30.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Committee on

Architecture and Design Funds, 2014 © Hipgnosis

KLAUS VOORMANN GERMAN BORN 1938

ROBERT WHITAKER (PHOTOGRAPHER) BRITISH 1939 - 2011

Parlophone Records, London (Record Label) British Est.

1923

Album Cover For The Beatles, Revolver 1966

Lithograph

Dimensions: 31.4 x 31.4 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Christian

Larsen, 2008

© Klaus Voormann and Robert Whitaker

MARTIN SHARP AUSTRALIAN 1942 - 2013

ROBERT WHITAKER (PHOTOGRAPHER) BRITISH 1939–2011

REACTION RECORDS (RECORD LABEL) BRITISH 1966- 1967

ALBUM COVER FOR CREAM, DISRAELI GEARS 1967

Lithograph

Dimensions: 30.5 x 30.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Committee on

Architecture and Design Funds, 2014

© Estate of Martin Sharp / Licensed by Copyright

Agency, 2018

RON HERRON

CITIES: MOVING, MASTER VEHICLE – HABITATION PROJECT,

AERIAL PERSPEDTIVE 1964

Ink and Graphite on Tracing Paper

Dimensions: 55.2 x 83.2 cm

Credit: Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation

Ron

Herron, a founding member of Archigram, the influential British group known for

its admixture of science-fiction and pop culture, created his Walking City out

of an indefinite number of giant roaming pods containing different urban and

residential areas. The pods could be connected by retractable corridors and,

together, form a conglomerate metropolis. This literally mobile and

indeterminate architecture was not so much a serious proposition for a

structure as a commentary on the way in which change dominates every aspect of

the modern city.

Publication

excerpt from an essay by Bevin Cline and Tina di Carlo, in Terence Riley, ed., The Changing of the Avant-Garde: Visionary

Architectural Drawings from the Howard Gilman Collection, New York: The

Museum of Modern Art, 2002, p. 54.

YONA FRIEDMAN

SPATIAL CITY, PROJECT, AERIAL PERSPECTIVE 1958

Ink on Tracing Paper

Dimensions: 21.3 x 27.3 cm

Credit: Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation

© 2018 Yona Friedman

The

Spatial City (Ville spatiale) is an unrealized theoretical construct

inspired by the housing shortage in France during the late 1950s and by Yona

Friedman's deep belief that housing plans and structures should allow for the

free will of the individual inhabitants. Not wanting to displace the city

below, Friedman raised a second city fifteen to twenty meters above the

existing one. The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived

and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure. The

layout of each level would occupy no more than fifty percent of the overall

structure in order to provide air and light to each residence as well as to the

city below. The project was designed for construction anywhere, and meant to be

adapted to any climate.

Publication

excerpt from an essay by Bevin Cline and Tina di Carlo, in Terence Riley,

ed.,

CESARE CASATI ITALIAN BORN 1936

C. EMANUELE PONZIO ITALIAN 1923 - 2015

PILLOLA LAMPS 1968

Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene and Acrylic Plastic

(1-5)

Dimensions: 55.2 x 13.0 cm Diameter (Each)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Celeste Bartos

Purchase Fund, 2000

© Cesare Casati

ROBERTO MATTA CHILEAN 1911 - 2002

KNOLL INTERNATIONAL, NEW YORK (MANUFACTURER)

AMERICAN

EST. 1938

Malitte Lounge Furniture 1966

Wool and Polyurethane Foam (a-e)

Dimensions: 160.0 x 160.0 x 63.5 cm (Overall)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Knoll

International, 1970

© Roberto Matta Estate

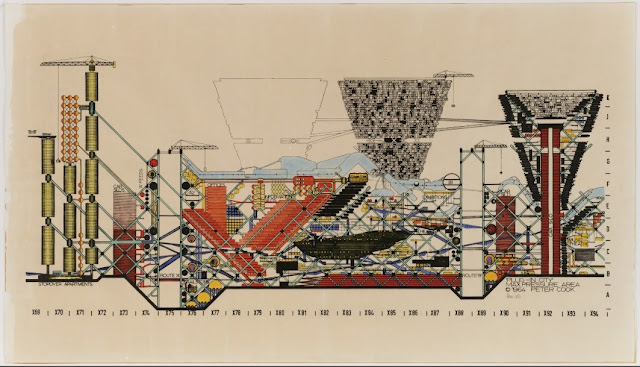

PETER COOK

PLUG-IN CITY: MAXIMUM PRESSURE AREA, PROJECT (SECTION) 1964 (DETAIL)

PETER COOK

PLUG-IN CITY: MAXIMUM PRESSURE AREA, PROJECT (SECTION) 1964

Ink and Gouache on Photomechanical Print

Dimensions: 83.5 x 146.5 cm

Credit: Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation

© Archigram 1964

Plug-in

City is one of many vast, visionary creations produced in the 1960s by the

radical collaborative British architecture group Archigram, of which Cook was a

founding member. A “megastructure” that incorporates residences, access routes,

and essential services for the inhabitants, Plug-in City was designed to

encourage change through obsolescence: each building outcrop is removable, and

a permanent “craneway” facilitates continual rebuilding. Between 1960 and 1974,

Archigram published nine provocative issues of its magazine and created more

than nine hundred exuberant drawings illustrating imaginary architectural

projects ranging in inspiration from technological developments to

counterculture, from space travel to science fiction. The group’s work opposed

the period’s functionalist ethos; Archigram designed nomadic alternatives to

traditional ways of living, including wearable houses and walking

cities—mobile, flexible, impermanent architecture that they hoped would be

liberating.

JOE COLOMBO ITALIAN 1930 - 1971

Kartell S.p.A., Milan (manufacturer) Italian

est. 1949

UNIVERSALE STACKING SIDE CHAIRS 1967

Polypropylene and Rubber (1-3)

Dimensions: 73.7 x 41.9 x 47.0 cm (Each)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of the

Manufacturer, 1988

© Joe Colombo Estate Photo: Ignazia Favata/Studio Joe

Colombo

ETTORE SOTTSASS

THE PLANET AS FESTIVAL: STUDY FOR TEMPLE FOR EROTIC

DANCES,

PROJECT (AERIAL PERSPECTIVE AND PLAN) 1972-1973

Graphite and Cut-and-Pasted Gelatin Silver Print on Paper

Dimensions: 35.4 x 32.1 cm

Credit: Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation

© 2018 Ettore Sottsass

TOMOHIRO NISHIKADO JAPANESE BORN 1944

TAITO CORPORATION, TOKYO ( MANUFACTURER &

PUBLISHER )

JAPANESE EST. 1953

Space Invaders 1978 Video Game Software

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of the Taito

Corporation, 2013

© Taito Corporation, 1978. All Rights Reserved

GAETANO PESCE ITALIAN BORN 1939 BRACCIODIFERRO,

GENEVA ( MANUFACTURER ) SWISS 1970- 1975

MOLOCH FLOOR LAMP 1970 - 1971

Metal Alloy and Steel

Dimensions: 229.9 x 286.7 x 86.0 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of

The Manufacturer, 1972 © Gaetano Pesce

RAY TOMLINSON AMERICAN 1941 - 2016

@ 1971 ITC AMERICAN TYPEWRITER MEDIUM

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Acquired, 2010

© Ray Tomlinson Estate

ANDY WARHOL, AMERICAN 1928 - 1987

BILLY NAME (PHOTOGRAPHER) 23, AMERICAN BORN 1940

CRAIG BRAUN (DESIGNER), AMERICAN BORN 1939

JOHN PASCHE (TYPOGRAPHER) AMERICAN BORN 1945

Rolling Stones Records, London (Record Label) British

1970–92

Album Cover For The Rolling Stones, Sticky Fingers 1971

Lithograph With Metal Zipper

Dimensions: 30.5 x 30.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Committee on

Architecture and

Design Funds, 2014

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

/ ARS.

Licensed by Copyright Agency, 2018

INNER & OUTER WORLDS

Many artists in the 1920s and 1930s broke from the

formal restraint and rational order of abstraction to embrace narrative excess

and the unconscious. Looking to both internal and external landscapes, their

works draw on forms in nature and imbue everyday observations with a sense of

the uncanny.

Surrealism, which began as a formal movement in Paris

but also attracted more casual and widespread fellow travellers, comprised two

dominant approaches. Painters including Salvador Dalí, Yves Tanguy and René

Magritte applied, to quote Dalí, ‘the most imperialist fury of precision’ to

their canvases, making incongruous scenes appear possible through the

meticulousness of their technique. Others, such as Joan Miró, Jean Arp and

Meret Oppenheim adopted biomorphic forms, evoking the soft structures of living

organisms.

As the looming Second World War forced many of these

artists to disperse from Europe, their networks became more far-reaching and

came into contact with longstanding cultural traditions. In Cuba, Wifredo Lam

merged Surrealist aesthetics with the religious iconography of Afro-Cuban

Santeria. In Mexico, Frida Kahlo cited native folklore and nineteenth-century

devotional paintings in her dreamlike canvases.

The work of various American artists during this

period similarly engages both physical and psychic landscapes. Edward Hopper’s

desolate scenes possess a palpable psychological charge; highly detailed

drawings by Georgia O’Keeffe and photographs by Imogen Cunningham render flora

otherworldly; and the architect Frederick Kiesler’s amoebic Endless House was

designed to negotiate the relationship between the individual and his or her

environment, making room for ‘the “visitors” from one’s own inner world’.

EINSTEIN AND 20TH-CENTURY ART: A ROMANCE OF MANY

DIMENSIONS

BY PROF. LINDA DALRYMPLE HENDERSON - THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AUSTIN

BY PROF. LINDA DALRYMPLE HENDERSON - THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AUSTIN

Although sharing Dalí’s organic form language, Matta

and his young colleagues rejected the clearly three-dimensional perspectival

space within which Dalí’s watches deform (Plate 1) in favor of a dimensionally

suggestive amorphous space with no definite horizon or clear spatial

orientation. The young Surrealists also embraced non-Euclidean geometry whole