MARK BRADFORD: THE ART OF PRODUCTIVE DISSENT BY SARAH LEWIS

MARK BRADFORD: THE ART OF PRODUCTIVE DISSENT BY SARAH LEWIS

On October 26, 1963, President John F. Kennedy

delivered a lyrical homage to the artist’s indispensable model of active

citizenship through productive dissent. He began the speech slowly, thanking

the community gathered that day in Amherst, Massachusetts, calling out specific

honored members and distinguished guests, leaving no segment out. His cadence

gained momentum as he soberly acknowledged the state of crisis both on domestic

and international fronts. Kennedy then opened into a broad, impassioned

manifesto. His voice would crescendo with his stated belief: “If sometimes our

great artists have been the most critical of our society, it is because their

sensitivity and their concern for justice, which must motivate any true artist,

makes him aware that our nation falls short of its highest potential. I see

little of more importance to the future of this country than full recognition

of the place of the artist.” One of the contributory features of the artist in

society, Kennedy observed and lauded, was to “question power.” 1 The poetry of

the speech came with Kennedy’s empathic homage to the artists who know their

role is not necessarily a popular one but are compelled by a sense of justice

to heed the call.

“He’s just said it all,” Mark Bradford told me after I

played him Kennedy’s speech in the office of Bradford’s Los Angeles studio.2

Bradford had just been selected to represent the United States at the 2017 Venice

Biennale. He was preparing an exhibition that would be both a statement and a

societal intervention—a social critique—an extension of his increasingly active

landmark community-based work. We listened and sat for a while in silence. We

have been colleagues and friends for over ten years. I had never sat with him

in a state of pregnant quiet for quite so long. Kennedy does not plead. His

voice dips in register when he makes his assured statement about the central

function of this particular type of artist on the domestic and international

stage. The speech began as a eulogy of Robert Frost, the President’s

inaugural poet. Yet in a draft of the speech, we see that Kennedy cut out any

ideas that did not center on his broader, iconoclastic argument about artistry,

critique, and citizenship.3 Perhaps he knew that his speech would become one of

the central texts on the role of the artist in civic society. Perhaps he knew,

too, that it might help to frame the significance of landmark events of

artistic achievement around the globe. Around the time of Kennedy’s speech,

Alan Solomon, commissioner of the U.S. Pavilion for the 1964 Venice Biennale,

traveled to Italy. His aim was to expand the physical footprint of the

Pavilion, notably smaller as it was than those of other countries. The project

was receiving federal funding and the architect Philip Johnson had offered to

redesign the building for free.4 With Kennedy’s assassination, though, the

expansion plan came to a halt. Solomon’s ambitious exhibition still required

additional space beyond that of the pavilion. He found it by roving, locating

space in the recently closed U.S. Consulate. There he would train the Biennale

public’s gaze on developments since Abstract Expressionism’s landmark

transformation of everyday objects with a group show of American artists

including Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Before the 1964 Venice

Biennale, no American artist had won the grand international prize. That

changed with the selection of Rauschenberg that year. Decades later, Bradford’s

work for the 2017 Venice Biennale offers an urgent reconsideration of the

stakes of Solomon’s actions and Kennedy’s words. This is not merely because

Bradford’s work is in dialogue and lineage with Rauschenberg; “I think if

Rauschenberg were pulling from the streets now, he and I would be fighting for the billboards,”

Bradford once said.5 But Bradford’s engagement with the everyday in his

abstractions has a different accent on the social from Rauschenberg’s: he

intervenes in public spheres that fall outside the logic of art-world networks,

namely in underground economies and underserved communities central to social

justice work today. What can come of an artist pushing even further past the

walls of the U.S. Pavilion to grapple with the nexus between art and the

everyday? What is the contributory function of the artist in society to offer a

model of productive dissent? These questions frame the stakes of his work. With

Bradford’s selection, the commissioner of the U.S. Pavilion for 2017, Christopher

Bedford, found himself like Solomon decades before him, roving outside the

pavilion he would co-curate with Katy Siegel. Bradford wanted to look for what

he calls “sites of need” beyond the Venice Biennale grounds. Regardless of

where he goes, he asks two questions that sound more like what you might hear

from a community organizer, a social worker, or a politician: what does the

community need and how can I give them access to it? These questions are the

filter for his ethical practice. “I always focus on need.

Even in my artwork where I take a merchant poster, it really has to do with highlighting need,” he told me. Bradford’s hunt for need led him to train his gaze on Venice’s prison merchant collectives, sustainable cooperatives in which prison inmates make and sell products and artisanal goods. He might have focused on different topics - “race, Hollywood films, Italian cinema, and visual stereotypes” - yet he felt that the political moment made other statements more urgent: “All of the police shootings started. One after another,” he said, recalling the U.S. context surrounding his being named as the 2017 artist representing America at the Venice Biennale. It felt as if “the center was collapsing, so then it shifted. That’s when my mind went to collapse. Our political, spiritual collapse—AIDS, drugs, the penal system, foster care, the rise of the faith church, rap. It laid so heavy on the center that it just collapsed.” There are twelve prison merchant collectives in Venice; Bradford has adopted one, Rio Terà dei Pensieri. Interested in helping its members transition back into society, he leased a space on behalf of the collective for six years. The project is called Process Collettivo. Bradford’s act—part of what Bedford has called the artist’s ethos of “absolute locality” - can be distinguished from social work, with its dual-pronged aim of intervention and symbolism.6 His goal is to create a social cognate to his realist abstractions, which center our gaze on marginalized communities in the neighborhoods where he finds himself—from South Central Los Angeles to, as a global citizen, communities around the world.

Bradford’s aim is not proscriptive. “You can do with it

what you want. You can do nothing. You can do a little bit. It’s your choice,”

he said to me about his expectations for the response to the

prison-merchant-collective project. He hopes that it will make viewers reflect

on the international penal system and the asymmetries between race and equity

that it represents. Over the course of our conversation, he let slip another

secret wish: “There are twelve prison merchant collectives in Venice. Wouldn’t

it be great if twelve private philanthropists adopted them? Wouldn’t that be

great?” he asked hypothetically, letting the idea sit in the air. Then he

pulled back: “I’m not going to preach. I’m just going to lay it at your feet.

I’m just going to give the art world some suggestions.” He then

paused as if settling in on how best to describe the gesture of his Venice

intervention. “I’m just going to create a map,” he said, “a road map.” He left

it there. Bradford’s social intervention is a radical way of rethinking

cartography—part of the foundational form of his artmaking practice. It is a

way to question what we consider proximate to our creative communities. The

circumambulation that has been at the heart of Bradford’s painting practice of

social abstraction—roving around to find merchant posters and signs of economies

that have fallen off the grid in his surrounding community—has made him

question the possibilities of his role as a citizen. This is to say, Bradford’s

idea of mapping—engaging with the areas of crisis that he has long focused on

in his work—has become the conceptual template for his entire practice. If it

was ever true that his work was bifurcated between his studio and his social

interventions, increasingly now both have one clear animating force: to point

to sites of need in communities that have fallen outside the art-world map. The

result is work that coheres as the model of critique and counter-statement that

Kennedy outlined as the unique visionary contribution of an artist concerned

with justice.

Many know of Bradford’s projects of social dissent through his organization Art + Practice, based in Leimert Park, Los Angeles, yet each extends a much longer history of such work. Earlier projects of the artist’s—the maleteros project and The Mark Bradford Project in particular—were steps toward the conceptual merger between his studio and his social interventions, challenging the way in which cultural communities often ignore proximate sites of need. In 2005, Bradford worked with insite, an organization creating collaborative public-art projects in the San Diego–Tijuana border region, to legitimate the work of the maleteros, the unrecognized porters at the U.S.- Mexico border. These porters operate largely without organizing practices for their work—without signs and sites where they can gather and store their wares—shopping carts using to make their labor more efficient in their handling of bags. Bradford’s intervention was to correct that by creating bright yellow-and-black signage to be placed near unionized states anctioned work sites and by carving out places for storage. Years earlier, his work had engaged with the idea of informal mercantile economies, communities that cannot be represented spatially but exist around formal networks, as Michel Laguerre has described in his book The Informal City.7

The communities of Latino

day-laborers in Los Angeles, referred to by the slang name “los moscos,” became

the subject of his eponymously titled painting from 2003, in which cubic and

rectangular accents of yellow, red, pink, and blue pierce the black paper as if

to force an increased visibility for the group. In 2005, with the maleteros

project, we see the beginnings of the artist’s dual-pronged practice, his way

of inhabiting his paintings through specific social interventions that

challenge the boundaries we draw around communities based on economic condition

and societal need. A year later he would start to engage with his

merchant posters in his paintings. In 2010, on the occasion of Bradford’s first

survey exhibition, organized by the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus,

Ohio, the artist initiated The Mark Bradford Project, which ran in Chicago

during the year before the show traveled to the city’s Museum of Contemporary

Art. From September 2010 through May 2011, Bradford worked with an

expanded set of stakeholders in Chicago’s cultural community—the Robert

Lindblom Math & Science Academy High School and you media, a digital space

for teens based at the Harold Washington Library Center. One student was so

taken with Bradford’s focus on mapping communities that she decided to map her

father’s journey from Mexico to the United States, depicting him as “a cowboy,

a hero,” she said.8 Bradford would say at the time that he saw the entire piece

in Chicago—the collaboration with the kids and his survey exhibition—as one

large work of social abstraction.

It is tempting to frame Bradford’s community-based

projects through the term “social practice.” Yet I would argue that there are

two reasons why scholars and curators have come just shy of doing so. I will

not dwell here on what is perhaps the most glaring of those reasons: Claire

Bishop, in tracing the history of social practice, has argued that many

practices since the 1990s have created a binary out of aesthetics and

engagement; in the name of participatory action and social engagement, artists

have “renounced the vocabularies of contemporary art” for the sake of

“micropolitical gestures.”9 But Bradford refuses to adhere to this split.

Indeed, as Pablo Helguera notes, the generally favored term “social practice”

excludes a reference to artmaking itself.10 It is for a second, more urgent

reason that we must challenge the idea of the term “social practice” as

applicable to Bradford’s work: his interventions disengage and challenge the

model of site-specificity that undergirds the term. Miwon Kwon has provided a

historical account of the emergence of site-specific art in the 1960s, tracing

the move from consideration of a site as a physical space to an approach that is

more “discursively determined”—“one that is delineated as a field of knowledge,

intellectual exchange, or cultural debate.”11 The impulse behind this move was

manifold, but included an impulse that might at first seem to resonate with

Bradford’s work: “a desire to increase the engagement of art with the outside

world and everyday life.”12 Yet the type of site-specificity that Kwon adroitly

identifies is not, the artist claims, his conceptual genealogy. “When I’m

talking about site-specific, I’m actually talking about site-specific,”

Bradford told me, modulating his emphasis on the term. “Not site specific. A

real site. Walk the neighborhood. It won’t take you long to find need,” he

said. “You’ll find it within a . . . well, a five-mile radius is being generous.

My god.” Centering his comments around the primacy of very particular physical

places that obviate need, Bradford is challenging how we constitute the idea of

the constitutive community surrounding sites of culture. “I don’t know what it

means,” Bradford said, perhaps facetiously, when I asked him about the term

“social practice,” surrounded by part of the vast library in his office. Even

the name of his cofounded organization Art + Practice unwittingly calls into

question the term appropriate for his interventions. The addition symbol seems

to function as a stand-in, even a productive challenge. “Is it about

engagement, pushing beyond the studio to find a community,” I began to ask.

“Often a poor community,” Bradford said. He left it there.

If Bradford’s work is not a form of social practice,

it is a justice-oriented form of productive dissent. Dissent, philosopher

Tommie Shelby reminds us, is a means of asserting agency through a public

stance, a public symbolic rejection of current policies and practices. Dissent

does not seek to sway. It is, however, a particularly crucial act, Shelby

argues, when we shift our approach away from systemic inequality to a model of

justice that shifts the onus from government to the affordances of citizens.13

Bradford’s dissent is not so much political as it is ethical. Its objective is

to alter the narrative embedded in the structure of creative communities where

sites of need often fall outside of the conversation. “There are a lot of

nonprofit spaces that are very good at giving access to contemporary art. They

are in every community,” he said. They’re in the Hispanic community, they’re in

the black community, they’re in the Asian community—you know, lots of them.

Basically, this whole model of social practice. But where’s need? Where is the

need? . . . When the museum talks about arts education, they’re only really

talking about the access part. But they’re always saying, “How do we reach more

people? How do we make it more dynamic? Why aren’t there more kids involved?”

I’m thinking, Well, there’s a whole other side.

That “other side” involves that act of addressing need as a more proximate endeavor. Recently, Bradford mused aloud about what it might mean to let the idea exist in the round. “I think it has to be a new model,” he said. “If you want to move outside of the museum walls, if you want the museum walls to be more animated, you’ve got to start addressing need. The programs that we have in the art world are fine. But if you want to be a little more dynamic, why not . . . you know I’ll be radical here,” he said, then paused to readjust his position in his chair. “Why not carve out a thousand or two thousand square feet and have that part of the institution to address a need in the community? Say a contemporary art center is next to a women’s shelter. Why not say let the museum say, ‘Here is some space that you can use for $25 a year.’ You know what? Why not?”

Art + Practice—cofounded by Bradford, his partner the

neighborhood activist Allan DiCastro, and Eileen Harris Norton—is a

counter-statement, a physical emblem to counter the idea of distance often

built into philanthropy. The organization reconceptualizes how space can

address needs in the Leimert Park community, where, it is now well-known,

Bradford grew up working in his mother’s hair salon, which he would later

convert into his studio. There he would often see young people on the street

during daytime hours and learned that they were foster kids. According to

recent statistics, after their emancipation from foster care, only 1 percent of

foster youth in California will go on to college, 25 percent will be

incarcerated, and 36 percent will be homeless.14 The project that started as

Bradford cofounding a space to provide foster youth with access to art and

media classes has grown in a few years to its provision of fundamental needs

for them, such as securing housing and job training. A retail shop and a café

are now under construction across the street from a gallery-quality exhibition

space with shows run by partners like the Hammer Museum, coupled with an

artist-residency program. If Art + Practice is a new model, that is because it

reverses what one might call the busing model of culture, the unilateral

template that brings a particular community to a cultural center. “What if an

art center didn’t require a bus trip? What if art was of the neighborhood, and

not outside it?” Bradford said. He was not asking, of course, about

transportation, but about the implicit cultural value we assign to

socioeconomic communities. “So many ideas are only available to the middle

class. Bring culture to this local community and see what they say,” Bradford

told me as we drove into his neighborhood, as we had done many times before.

What does a community deserve? It is the rhetorical question that Art +

Practice Executive Director DiCastro uses as an organizational framework. It

began when he was living in Los Angeles’s MidCity neighborhood and noticed that

the curbs and hydrants there were never painted, as they were in more affluent

sections. When he went down to the Los Angeles Department of Transportation to

see if they might launch this improvement work, the clerk questioned why the

city would ever paint the curbs and hydrants and added, as a practical reason,

that the area has a lot of curbside weeds. DiCastro left. Every weekend for a

month, he pulled all the weeds by hand on his street for one mile in either

direction. He would put the weeds in dog-food bags in the back of his truck and

haul them home. “I called her back a month later. They painted the curbs,”

DiCastro said. When I last visited Art + Practice, Bradford and I toured a new

space with DiCastro on what has become a multisite campus. The former Brockman

Gallery is now part of a complex that serves larger services—public programs

and a retail space that will be run in part by foster youth, a condition of any

vendor who leases the exquisitely modeled space. Art historian Daniel

Widener states that the Brockman Gallery in Leimert Park, founded in

1967 by Alonzo and Dale Davis, was “the oldest black-owned art gallery west of

the Mississippi” by the late 1990s, when it closed.15 In the 1960s, Leimert

Park, a planned community laid out by the Olmsted Brothers firm (run by the

sons of the nineteenth-century landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted),

shifted from being largely white to becoming the home of a multi sectoral black

community sited within and around working-class Crenshaw, but with proximity to

what were then known as “black Beverly Hills” areas such as Baldwin Hills,

Ladera Heights, and View Park. Widener traces the way in which the postwar era,

specifically between 1942 and 1992, saw the arts in Southern California gain

primacy as a structural force in a multigenerational movement for social change

and for “a wide-ranging critique of American society.”16 The Brockman Gallery

functioned as a locus for both exhibitions and artistic exchange. It was a

space that pulsated with activity, from exhibitions and courses to federally

funded mural projects. Now, this storied former gallery space continues that

mission under a new guise. The day I toured the newly opened exhibition space,

which then housed a show of the work of the sculptor Fred Eversley, Bradford,

DiCastro, and I talked with a guard who, it turned out, had been in the

foster-care organization operated by Art + Practice. She now worked in the

gallery space, supporting her two children. She had a second job working the

graveyard shift. “You know what we need now?” Bradford said. “Daycare.” If

there is one artist who functions as a cousin to Bradford in his politics of

dissent, it is Rick Lowe, cofounder of the pathbreaking Project Row Houses, in

the Ninth Ward of Houston, Texas. There Lowe has married an artist-residency

program with the Young Mothers Residential Program; all share the shotgun

houses he purchased so that they might be transformed, with the aim of

community revitalization and empowerment. Lowe, whose model is inspired by the

work of John Biggers and the social sculpture of Joseph Beuys, serves on the

board of advisors for Art + Practice. Yet Bradford’s vision is self-consciously

singular, honed in isolation. “ I’m interested in the history of abstraction,

of unpacking the ’50s,” Bradford has said. “What does it mean to unpack that

moment, when both Jackson Pollock and Emmett Till were on magazine covers? ”17

Few models function as analogues to Bradford’s work

because it is conceptually akin to work in another medium, the

social-documentary photography of the 1940s and ’50s, being animated by the

same impulse of dissent that made the photographer Gordon Parks often use the

medium to show racially divided communities in crisis. Like Bradford, Parks

trained his lens on signs, what we might call merchant posters of our racial

past, which regulated the flow of race and capitalism at the height of Jim Crow

segregation. He began by roving, walking around Washington, D.C., in the early

1940s under the auspices of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), where

photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, and Walker Evans

had been charged to educate the public about Depression-era conditions in the

United States. Parks didn’t know much about Washington so FSA Director Roy

Stryker gave him an unusual first assignment: to leave his camera in the office

and walk around the city, visiting a department store to buy a coat, a

restaurant to get a bite to eat, and a movie theater for entertainment. Parks

came back to the office having been denied service or ignored in each

establishment. “What do you intend to do about it?” Stryker said. Parks

answered with his camera. This roving tour animated the photographer’s

signature

work, American Gothic, an image of FSA office-cleaner

Ella Watson standing with her broom and mop in front of the American flag. It

also informed landmark images such as Department Store, Mobile, Alabama (1956),

which documents a “merchant sign” enforcing segregation in the South. Here the

neon sign “Colored Entrance” frames a young girl and a woman in sharp profile,

both wearing white—heels, earrings, dressed in Sunday best—while also labeling

the telescoping view of the street receding behind them, as if to suggest the

pervasive practice of segregation in the 1950s in the Jim Crow South. Parks answered

the call to dissent with his camera; Bradford answers with his familiar

materials and means, reconfiguring our maps, the social abstractions we inhabit

daily, to define our cultural community.

Kennedy could likely never have imagined what an

artist such as Bradford would have done in Leimert Park, yet at the conclusion

of his eulogy-turned-speech he expressed hope for what can now be found in

communities like it. He saw the connection between society’s valuing of

community strength and diversity and its ability to “reward achievement in the

arts as we reward achievement in business or statecraft.” He presciently laid

his hopes for this balance of “power” and “purpose” at the feet of the

citizen-artist, maintaining that the critique that comes from art “establishes

the basic human truths which must serve as the touchstone of our judgment.”18

The artist’s productive dissent is an affordance of civic society. It is a

feature that suggests an alternate possibility. Affordances in architecture

allow for dynamism: they anticipate changes in how one interacts with a given

space. The same applies to the world of practical design: modularity indicates

the full extent of how an object can be used; operation is signaled though

visual cues. Bradford’s work operates as just such an invaluable affordance,

drawing ever wider boundaries around cultural communities. At times, I have

wondered whether Bradford would ever hold office. Yet I realize now that he

already has: through his social projects of productive dissent he is redefining

and reanimating the office of increasingly global citizenship.

NOTES 1 John F. Kennedy, Jr., “The President’s

Convocation Address,” 1963. Reprinted courtesy the John F. Kennedy Library,

President’s Office Files, Speech Files, Box 47. Available online at

https://www.amherst.edu/library/ archives/exhibitions/kennedy/documents#Final (accessed

January 2017).

2 Mark Bradford, interview with the author, December

2016. Unless stated otherwise, all of this essay’s quotations of Bradford are

from this interview.

3 Available online at

www.amherst.edu/library/archives/ exhibitions/kennedy/documents#Draft (accessed

January 2017).

4 For more see Calvin Tomkins, Off the Wall: A Portrait of Robert Rauschenberg (New

York: Picador, 2005).

5 Bradford, interviewed for “Paradox,” art 21—Art in

the Twenty-First Century, Public Broadcasting Service, November 18, 2007.

Transcript available online at www.

art21.org/texts/mark-bradford/interview-mark-bradfordpolitics-process-and-postmodernism

(accessed January 2017).

6 Christopher Bedford, “Against Abstraction,” in

Bedford, Hilton Als, Carol S. Eliel, et al., Mark Bradford, exh. cat.

(Columbus, Ohio: Wexner Center for the Arts, and New Haven: Yale University

Press, 2010), p. 26.

7 Michel S. Laguerre, The Informal City (New York: St.

Martin’s Press, 1994).

8 See The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, The

Mark Bradford Project, video, 2011, available online at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NjAe8yEN0DQ (accessed January 2017).

9 Claire Bishop, “Participation and Spectacle: Where

Are We Now?” in Nato Thompson, ed., Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from

1991–2011 (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, and New York: Creative Time Books,

2012), p. 38.

10 Pablo Helguera, Education for Socially Engaged Art:

A Materials and Techniques Handbook (New York: Jorge Pinto Books, 2011).

11 Miwon Kwon, “One Place after Another: Notes on Site

Specificity,” October 80 (Spring 1997):26.

12 Ibid., p. 91. See also Kwon, One Place after

Another: SiteSpecific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT

Press, 2002).

13 Tommie Shelby, Dark Ghettos: Injustice, Dissent,

and Reform (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,

2016), particularly pp. 265–69 on dissent.

14 See www.therightwayfoundation.org/what-we-do

(accessed January 2017).

15 Daniel Widener, Black Arts West: Culture and

Struggle in Postwar Los Angeles (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2010), p.

159.

16 Ibid., p. 3.

17 Bradford, quoted in Alina Cohen, “AIDS,

Abstraction, and Absent Bodies: A Conversation with Mark Bradford,”

Hyperallergic, December 9, 2015. Available online at

http://hyperallergic.com/260045/aids-abstraction-andabsent-bodies-a-conversation-with-mark-bradford/

(accessed January 2017).

18 Kennedy, “The President’s Convocation Address.”

‘’ LOS MOSCOS ‘’, 2004

Mixed Media on Canvas

Dimensions: 125 × 190 1/2 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

GRACE & MEASURE, 2005

Mixed Media Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 90 × 120 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

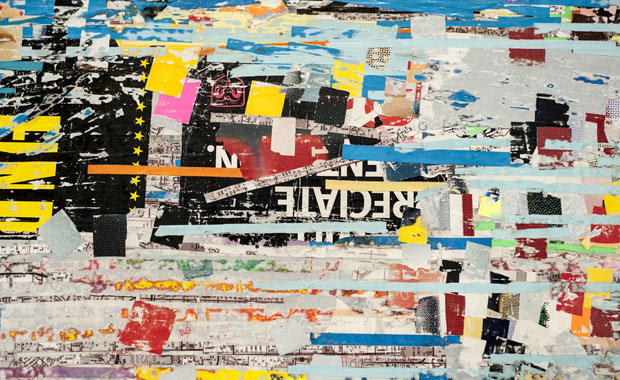

SCORCHED EARHT, 2006

Billboard Paper, Photomechanical Reproductions,

Acrylic Gel Medium,

Carbon Paper, Acrylic Paint, Bleach, and Additional

Mixed Media on Canvas

Dimensions: 241.94 x 300.36 x 5.72 cm

© Mark Bradford

ABOUT

THIS ARTWORK

The

layers in Scorched Earth create a topography that represents the

deep psychological and physical ruins of a disappeared people and another time

and place. In this work, Mark Bradford depicts an aerial map of an area that

has been blacked out. The blackness of this land mass resonates on many levels:

black as in the demographics of this neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, at one

time called “Negro Wall Street,” where many black-owned businesses thrived,

until a race riot erupted in 1921 and the violence obliterated this unique area

and its history; black, as the title suggests, meaning burnt or scorched; black

as in redacted; and black as in nothingness.

‘’ BLACK VENUS ‘’, 2005

Mixed Media Collage

Dimensions: 130 × 196 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

BLACK VENUS ( DETAIL ) , 2005

SAMPLE 2, 2015

Canvas

Dimensions: 157.5 × 121.9 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo

by Joshua White

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

TEMPORARY ( DETAIL ), 2005

DEAD HUMMINGBIRD, 2015

Canvas

Dimensions: 213.4 × 274.3 cm

Courtesy of the Artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Photo by Joshua White

© Mark Bradford

TEMPORARY, 2005

Mixed Media Collage and String

Dimensions: 130 × 196 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

UNTITLED, 2012

Inkjet With Spot Printing and Applied Texture

Dimensions: 35.6 × 27.9 cm

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

2871 EAST, 2012

Mixed Media Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 259.1 × 365.8 cm

© 2017 Mark Bradford

© 2017 Mark Bradford

2871 EAST ( DEATIL ), 2012

SAMPLE 3, 2015

Canvas

Dimensions: 157.5 × 121.9 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo

by Joshua White

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

‘’ ANALOG ‘’, 2004

Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 125 × 125 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

GIANT, 2007

Torn-and-Pasted Printed Paper on Canvas

Dimensions: 258.8 x 363.2 cm

Credit: Promised Gift of the Ovitz Family Collection

© 2017 Mark Bradford. Courtesy

© 2017 Mark Bradford. Courtesy

Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

DISAPPEAR LIKE A DOPE FIEND, 2006

Mixed Media Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 47 3/8 × 61 1/8 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

BURN BABY BURN, 2002

Mixed Media on Canvas

Dimensions: 72 × 84 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

A

POTABLE WATER ( DETAIL ), 2005

AA

POTABLE WATER, 2005

Mixed Media Collage

Dimensions: 130 × 196 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

A

A

POTABLE WATER ( DETAIL ), 2005

THE DEVIL IS BEATING HIS WIFE (DETAIL ), 2003

THE DEVIL IS BEATING HIS WIFE, 2003

Billboard Paper, Photomechanical Reproductions, Permanent-Wave end Papers,

Billboard Paper, Photomechanical Reproductions, Permanent-Wave end Papers,

Stencils, and Additional Mixed Media on Plywood

Dimensions: 335.3 x 609.6 cm

Dimensions: 335.3 x 609.6 cm

© Mark Bradford

Z

Mark Bradford’s abstractions unite high art and

popular culture as unorthodox tableaux of unequivocal beauty. Working in both

paint and collage, Bradford incorporates elements from his daily life into his

canvases: remnants of found posters and billboards, graffitied stencils and

logos, and hairdresser’s permanent endpapers he’s collected from his other

profession as a stylist. In The Devil is Beating His Wife, Bradford

consolidates all these materials into a pixelised eruption of cultural

cross-referencing. Built up on plywood in sensuous layers ranging from silky

and skin-like to oily and singed, Bradford offers abstraction with an urban

flair that’s explosively contemporary.

MARK BRADFORD: THE ART OF PRODUCTIVE DISSENT

'' I may pull the raw material from a very specific place, culturally from a particular place, but then I abstract it. I’m only really interested in abstraction; but social abstraction, not just the 1950s abstraction. The painting practice will always be a painting practice but we’re living in a post-studio world, and this has to do with the relationship with things that are going on outside."

Mark Bradford

MARK BRADFORD: THE ART OF PRODUCTIVE DISSENT

STRAWBERRY ( DETAIL ) 2002

STRAWBERRY 2002

STRAWBERRY ( DETAIL ) 2002

HORRIBLE SHARK , 2011

Mixed Media on Canvas

Dimensions: 260 x 366 cm.

Dimensions: 260 x 366 cm.

© 2017 Mark Bradford

ON A CLEAR DAY I CAN USUALLY SEE ALL THE WAY TO

WATTS, 2001

Mixed Media on Canvas

Dimensions: 72 × 84 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

WHITE PAINTING( DETAIL ), 2009

WHITE PAINTING, 2009

Mixed Media, Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 259 x 366 cm

Mixed Media, Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 259 x 366 cm

© Mark Bradford

Z

Mark

Bradford’s abstractions unite high art and popular culture as unorthodox

tableaux of unequivocal beauty. Working in both paint and collage, Bradford

incorporates elements from daily life into his canvases such as remnants of

found posters and billboards and hairdresser’s permanent endpapers. In White

Painting, Bradford

uses paper exclusively to replicate the effect of paint. Scratching and sanding

through the layers to reveal strata of colours and embedded images, his palimpsest surface draws connotations to both abstract

expressionism and street art, recontextualising the sublime traditions of high

art with an urban flair that’s explosively

contemporary.

WHITE PAINTING( DETAIL ), 2009

UNTITLED (MB

9693), 2009

Mixed

Media Collage

Dimensions:

55.9 × 71.1 cm

© 2017

Mark Bradford

CIVIL BRAND, 2005

Mixed Media Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 72 × 85 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

ELGIN GARDENS, 2015

WINDOW SHOPPER, 2005

Mixed Media Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 48 × 60 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

BACKWARD C ( DETAIL ), 2005

UNTITLED, 2002

Acrylic,

Burnt Paper Collage on Paper Laid on Canvas

Dimensions:

41.6 × 46.5 cm

© Mark Bradford

BACKWARD C, 2005

Mixed Media Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 84 × 120 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

LOS MOSCOS, 2004

Mixed Media on Canvas

Dimensions: 125 × 190 1/2 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

REBUILD SOUTH CENTRAL, 2015

Canvas

Dimensions: 109.2 × 243.8 cm

Courtesy of the Artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo

by Joshua White

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

UNTITLED, 2007-2009

Mixed Media Collage on Paper

Dimensions: 71.1 × 55.9 cm

© 2017 Mark Bradford

© 2017 Mark Bradford

A WITCH IN A

BOTTLE, 2012

A WITCH IN A

BOTTLE ( DETAIL ), 2012

WHEN WE RIDE, 2006

Mixed Media Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 46 3/8 × 62 1/4 inches

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

RIDIN ‘

DIRTY ( DETAIL ) - 2006

Mixed

Media Collage on Paper; 78 panels,

Dimensions: 109

× 336 inches

Courtesy

Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

LIGHTS & TUNNELS, 2015

Canvas

Dimensions: 213.4 × 274.3 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo

by Joshua White

© Mark Bradford

© Mark Bradford

EXODUS, 2006

Mixed Media Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 48 by 60 in. 121.9 by 152.4 cm.

© 2017 Mark Bradford

Mixed Media Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 48 by 60 in. 121.9 by 152.4 cm.

© 2017 Mark Bradford

A

MARK BRADFORD

Known for his expansive multi-layered collaged paintings incorporating

materials found in the urban environment, Mark Bradford’s work addresses

spontaneous systems and networks that materialise within cities, such as

alternative economic exchange, itinerant communities, and other socio-political

pathways.

Visually complex and often cartographic in form, Bradford’s paintings

incorporate elements of the everyday – from end papers used for perming hair

(associated with his background in hairdressing) to remnants of billboard

posters, polyester cord, caulking, bleaching agents and carbon paper. Using

such materials gathered within the locale of his studio in South Central Los

Angeles, Bradford's paintings are ostensibly abstract in a formal sense, but

referential in content. At first glance, the work corresponds with that of

‘Affichiste’ artists such as Raymond Hains and Jacques Villeglé; yet Bradford

is less concerned with a commentary on consumerism, than with the specific

conditions that shape communities. This is most clearly identified in the works

featuring what he terms as ‘merchant posters’ found in his immediate

neighbourhood. Affixed to cyclone fencing, erected around buildings left

derelict after the 1992 Los Angeles riots, these billposters advertise, in bold

graphics, services targeted directly at local inhabitants. The topics – ranging

from foreclosure and paternity testing to loan credit and pest control –

coalesce to form a narrative of desolation and, as Bradford has observed,

reveal 'the invisible underbelly of a community'. In ‘A Thousand Daddies’, for

example, multiple billboards advertising child custody services provide the

foundation, with the letters broadly outlined in cord, over which layers of

other posters and paper are pasted before being sanded back in part. This

process of décollage or accretion reveals glimpses of luminous colour from the

notices buried within.

Bradford’s practice also encompasses video, prints and sculptural

installations. For the 55th Carnegie International in 2008, he created an

installation for the rooftop of the museum. In reference to the stranded

victims of Hurricane Katrina, he spelled out the words ‘HELP US’ in white

stones, which was only visible from an aerial viewpoint. Later that year,

Bradford created ‘Mithra’, regarded as one of the most iconic works of the

‘Prospect: New Orleans’ biennial. A three-storey ‘ark’ made from stacked

shipping containers positioned on a vacant plot in the Lower Ninth Ward, the

sculpture’s immense surface was covered in battered poster boards and

advertising found around the city in the wake of the disaster. As one

commentator noted, it could be simultaneously read as ‘a monument to futility

or a symbolic cry for salvation’.

Mark Bradford was born in 1961 in Los Angeles, where he lives and works. He

has exhibited widely, including groups shows such as the 12th Istanbul Biennial

(2011), Seoul Biennial (2010), the Carnegie International (2008), São

Paulo Biennial (2006), and Whitney Biennial (2006). Solo exhibitions include,

Aspen Art Museum (2011), ‘Maps and Manifests’ at Cincinnati Museum of Art

(2008) and '‘Neither New Nor Correct’ at the Whitney Museum of American Art

(2007). In 2009, Mark Bradford was the recipient of the MacArthur Foundation

‘Genius’ Award. In 2010, ‘You’re Nobody (Til Somebody Kills You), a large-scale

survey of his work was presented at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus,

before travelling to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; Museum of

Contemporary Art, Chicago; Dallas Museum of Art; and San Francisco Museum of

Modern Art.