A

SPANISH PAINTER PABLO PICASSO

EXPERIMENTATION OF ART

EXPERIMENTATION OF ART

A

b

SPANISH PAINTER PABLO PICASSO

EXPERIMENTATION OF ART

Spanish painter, sculptor, draughtsman, printmaker,

decorative artist and writer, active in France. He dominated 20th-century

European art and was central in the development of the image of the modern

artist. Episodes of his life were recounted in intimate detail, his comments on

art were published and his working methods recorded on film. Painting was his

principal medium, but his sculptures, prints, theatre designs and ceramics all

had an impact on their respective disciplines. Even artists not influenced by

the style or appearance of his work had to come to terms with its implications.

With Georges Braque Picasso was responsible for Cubism, one of the most radical re-structurings of the way that a work of art

constructs its meaning. During his extremely long life Picasso instigated or

responded to most of the artistic dialogues taking place in Europe and North

America, registering and transforming the developments that he found most fertile.

His marketability as a unique and enormously productive artistic personality,

together with the distinctiveness of his work and practice, have made him the

most extensively exhibited and discussed artist of the 20th century.

You may visit Pablo Picasso exhibition news at Art

Instıtute of Chicago to click below link.

http://mymagicalattic.blogspot.com/2013/04/picasso-chicago-at-art-institute-chicago.html

2. PRIMITIVISM & CUBISM 1906

- 1915

Source: Oxford University Press

In his paintings immediately

prior to the early Cubist paintings of 1908, Picasso had initiated the

breakdown of illusionistic space that he was to pursue with an apparently

greater intellectual rigour through Cubism, a style that over the course of

a decade secured his prominent place in the history of 20th-century art. For

Picasso, however, the restraint of Cubism was preceded by works

exhibiting a raw intensity and violence in part stimulated by his reading of

non-Western art, and aligned with European currents of primitivism (see Primitivism, §2). This dialogue of apparently

contrasting positions, between the intellect and the emotions, between forms of

classicism and expressionism and between the conscious

and the unconscious, provided the dynamic of much of Picasso’s work.

Picasso and Fernande Olivier

spent the summer of 1906 in Gosol, a remote Catalan village in the Pyrenees

where he came to terms with his experience of Iberian sculptures from Osuna,

which he had seen in the Louvre in the spring. He began in his work to make

reference to forms of archaic art and to make expressive use of distortion with

insistently rhythmical repetitions and contrasts. In Gosol, Picasso made his

first carved sculptures. The resistance of wood produced simplified forms akin

to those in his paintings. Gauguin’s work in the same medium, the most

immediate European precedent available to Picasso, had been known to him

through Paco Durio, a previous tenant in the Bateau-Lavoir; its primitivism had

been given authority by the retrospective held at the Salon d’Automne in 1906,

and it offered access to another major stimulus, the art of the Pacific

Islands. At the same Salon ten paintings by the recently deceased Cézanne were

exhibited. Resolving his response to the achievements of these two artists

preoccupied Picasso over the next year and helped define his later work. On his

return to Paris, Picasso quickly completed his portrait of Gertrude

Stein (1906; New York, Met.; for illustration see Stein,

(3)), which had been left partly obliterated in the spring after over 80

sittings, giving her a mask-like visage of monumental chiselled forms

compressed within a shallow space. The Stein portrait stands as a crucial shift

from observation to conceptualization in Picasso’s practice.

(I) ' LES DEMOISELLES D'AVIGNON '

The primitivism of Les

Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907; New York, MOMA) was more shocking still.

While it gestated from a series of preparatory drawings and underwent major

overpaintings during its production, it does not so much summarize Picasso’s

previous work as reframe his understanding of painting; he called it his ‘first

exorcism picture’. This radical picture, seen by friends in his studio and

designated by various appellations, was put aside and shown publicly only in

1916, when it was given its present title by Salmon. It was purchased by the

couturier Jacques Doucet in 1924 and acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New

York, in 1939 at the time of Picasso’s retrospective. Embedded in its matrix

are the vestiges of Picasso’s encounters with 19th-century artists: Ingres,

Manet, Delacroix, Cézanne and Gauguin. Initially conceiving it as a narrative

brothel scene, Picasso changed it to a vertical format, adopted a more

discontinuous sense of space for the setting, removed the male visitors and

reorientated the women to confront the (implicitly male) viewer. Controversy

surrounded its stylistic disjunctures, confused by Picasso’s own equivocal

statements. Rubin (1984) has argued that Picasso reworked the painting in late

June and early July after a visit to the African and Oceanic collections in the

Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. Although the painting has defeated

most efforts to specify African or Pacific sources, it records Picasso’s

reassessment of Gauguin’s primitivism and attests to the revelations accorded

by forms of non-Western carving in terms of conceptual principles of

representation and an emotively powerful evocation of magic and ritual. Linking

eroticism and the fear of death, the Demoiselles fixed an

image that was savage in style and violent in its dismemberment of the female

body.

In paintings such as Mother

and Child (1907; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 19) and wood-carvings such

as Figure (1907; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 238), Picasso probed the

fetishistic and conceptually simplifying aspects of primitivism. Although the

juxtaposition of discordant elements in the Demoiselles gave

way to internal pictorial coherence, in general his work of the following year

displays an astonishing diversity of handling. Picasso sundered and isolated

illusionistic conventions, using bright hues contrasted with subdued greys and

earth colours, striated hatchings against angular crumpled planes, and rhythmic

repetitions paired with bar-like outlines. In still-lifes painted in spring and

summer 1908 and landscapes executed in August at La Rue-des-Bois, Picasso

continued to reflect on the work both of Cézanne, which he had studied in depth

at the retrospective held at the Salon d’Automne of 1907, and of Henri

Rousseau, whom Picasso and Olivier fêted with a banquet in November.

By October 1907, and probably

earlier in the spring of that year, Apollinaire had introduced Georges Braque

to Picasso. In the winter of 1908–9 Picasso repainted his monumental Three

Women (St Petersburg, Hermitage). Possibly in response to Braque’s

Cézanne-influenced landscapes from the summer, in this work and a number of

still-lifes Picasso imposed a more consistent control both on the surface and

on illusions of space, after the example of Cézanne but with a greater concern

for physicality. In contrast to Picasso’s usual assertive individualism, the

invention of Cubism was such a joint effort

that even he and Braque sometimes had difficulty in distinguishing each other’s

work; Braque later described their relationship as that of mountaineers roped

together.

(II) ANALYTICAL CUBISM

In summer 1909 Picasso and Olivier spent four months at Horta de Ebro, where he made views of the village and landscape not only in paintings and drawings but also in photographs. The spatial continuity he admired in Cézanne’s work was treated in his own paintings, such as House on the Hill, Horta de Ebro (1909; New York, MOMA), in terms of nearly monochromatic tilted facets that fragment forms into a flow of light-dispersing surfaces. These discoveries were taken one stage further in pictures made in 1910 during a visit to the Catalan town of Cadaqués in the company of André Derain and his wife. In these works facets seem to be depleted of their substance, leaving a fragmented scaffolding of vestigial planar edges. In a series of etchings illustrating Jacob’s Saint-Matorel (1911; Paris, Geiser, 1933, nos 23–6) Picasso moved towards images that were increasingly transparent and difficult to interpret. The growing discontinuity of figurative fragments that characterized these methods, which came to be labelled Analytical Cubism, was especially apparent in three portraits of art dealers: Ambroise Vollard (spring 1910; Moscow, Pushkin Mus. F. A.), Wilhelm Uhde (spring 1910; St Louis, MO, Joseph Pulitzer priv. col., see Zervos cat. rais., ii, no. 217) and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (autumn, 1910; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.). While experiments in painting and sculpture had been closely interconnected in Picasso’s primitivism, in his Analytical Cubist phase he produced only Head of a Woman (Fernande) (1909; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 243) and two less satisfactory sculptures.

Picasso signalled his disaffection with the bohemian existence of the Bateau-Lavoir by moving in the autumn of 1909 to a new studio and apartment with maid in the vicinity of the Place Pigalle; he and Fernande began to hold regular open house there on Sundays. He sold paintings to the Russian collector Sergey Shchukin and to Gertrude Stein and Vollard, and exhibited internationally from Moscow to New York in 1910–12. Like Braque, however, with whom he worked very closely in this period, Picasso refused to participate in the Salon d’Automne or the Salon des Indépendants, in spite of the growing number of adherents of Cubism who made use of the Salons as a platform for their work.

After working with Braque at Céret in August 1911, Picasso was forced to return hastily to Paris in early September. The confession by Apollinaire’s friend Géry Piéret to the theft of several sculptures, including two Iberian heads sold to Picasso in 1907, had led to Apollinaire’s arrest for the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre. Although Apollinaire was later exonerated, he and Picasso both suffered concern for their status as foreign residents. The autumn marked a change in Picasso’s personal life. He began a liaison with Eva Gouel (Marcelle Humbert), whose presence in his life he commemorated not in portraits but in the words ‘ma jolie’, taken from a popular song, which he applied to the surface of paintings such as Woman with Guitar (‘Ma Jolie’) (1911–12; New York, MOMA). During his stay at Céret, Picasso had begun to deal openly again with more easily legible imagery after his experiments in the spring with nearly abstract paintings (sometimes labelled Hermetic Cubism). Using a pictorial scaffolding that coincided more clearly with the placement of still-life objects, Picasso filled the interstices with a scintillating touch similar to that used by the Neo-Impressionists. Following Braque’s example he employed stencilled lettering, which he soon exploited in verbal puns, masked meanings and multiple readings.

(III) FIRST COLLAGE

After painting still-lifes that employed lettering, trompe l’oeil effects, colour and textured paint surfaces, Picasso produced Still-life with Chair-caning (May 1912; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 36; for illustration), an oval picture suggesting a café table in perspective surrounded by a frame made of rope. This was the first example of collage, a form of painting or drawing that incorporates pre-existing materials or objects as part of the surface. On to the painted background Picasso applied a piece of oil-cloth printed with an illusionistic chair-caning pattern: the very kind of cloth commonly used as a table-covering in working-class kitchens. The three letters written just above the chair-caning, JOU, can be interpreted both as a fragment of the noun JOURNAL and as a verb indicating Picasso’s perception of his activity as a form of play. In the same year, probably following the invention of collage, Picasso applied similar principles to sculpture in three-dimensional constructions beginning with Guitar (cardboard, 1912; New York, MOMA). A revelation from African art, a Grebo mask, catalysed Picasso’s vision of the possibilities of spatially disjunctive arrangements of signs for object, form and volume. His invention of this radical new sculptural form was to have enormous repercussions not only for his own later work but also for later developments in modern sculpture.

(IV) PAPIERS COLLES & SYNTHETIC CUBISM

Picasso and Eva Gouel spent the summer of 1912 in Céret, Avignon and Sorgues, where they were joined by the Braques, but returned briefly to Paris in September to move into a new studio found for them by Kahnweiler on the Boulevard Raspail; at the end of the year Picasso signed a three-year contract with Kahnweiler, granting him exclusive purchase rights over his paintings. At Sorgues in mid-September Picasso saw Braque’s first papier collé, a variation of collage that employed not only ready-made materials such as newspapers but also purely invented shapes cut out of sheets of blank paper. On his return to Paris in October, Picasso also began to produce works in this medium, for example Violin and Sheet of Music (autumn 1912; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 368). Both collage and papier collé offered a new method not only of suggesting space but also of replacing conventional forms of representation with fragments of images that function as signs. They provided, in other words, a radically new way of dealing with the pictorial language that Picasso had been prising apart and isolating since the Demoiselles. Pasted newsprint helped Picasso to interpose references to tense pre-war politics, to social violence and absurdity and to artistic matters. During two further phases of his development of papier collé in 1913, Picasso discovered that shapes could acquire other meanings or identities simply by their arrangement, without requiring a resemblance to naturalistic appearances. A single shape might wittily and equally convincingly stand for the side of a guitar or a human head. Elements glued on to the surface, or hand-painted imitations of such material in a sophisticated double-take on the relationship between illusion and reality, were incorporated in subsequent paintings such as Geometric Composition: The Guitar (oil on canvas mounted on wood, 870×475 mm, spring 1913; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 38). Each element in the works of this phase, known as Synthetic Cubism, was carefully considered for the ways it could contribute to pictorial meaning.

In the same year that Apollinaire published Les Peintres cubistes: Méditations esthétiques (Paris, 1913), Picasso showed paintings in group exhibitions in Vienna and Prague, at the Armory Show in New York and at the Jack of Diamonds exhibition in Moscow; he also held his first large retrospective, comprising work from 1901 to 1912, at the Galerie Thannhauser in Munich. From mid-March Picasso and Eva Gouel spent five months in Céret, accompanied by Max Jacob and later by Juan Gris, and in August they moved into new quarters in the Rue Schoelcher. Although the designation of two phases of Cubism first made by Kahnweiler in Der Weg zum Kubismus (Munich, 1920), which distinguished between an analytical description of objects and a synthesis of information about an object into a more unified self-sufficient structure, has dated, the terminology remains; however, numerous works of this period resist rigid classification as examples of either Analytical or Synthetic Cubism. Woman in an Armchair (autumn 1913; New York, Mrs Victor Ganz priv. col., see Penrose and Golding, 1973, no. 131), resuming a favourite early theme, includes traces of Analytical Cubist colour and faceting as deliberate signs of other systems of representation within a Synthetic Cubist matrix. By contrast the Card Player (1914; New York, MOMA) appears more ironically detached, but it too rejects a single consistent reading by juxtaposing several kinds of pictorial space and illusionistic conventions.

The Demoiselles, as Picasso’s first major painting to feature stylistic disconnectedness, was followed by papiers collés and Synthetic Cubist paintings that significantly ruptured previous conceptions of style. By such means Picasso discovered that sets of pictorial conventions could be manipulated with the same freedom as individual components. In the unfinished painting The Painter and his Model (oil and pencil on canvas, summer 1914; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 53) and in portrait drawings of 1915, he startlingly made use of naturalistic conventions of drawing, shading and space; nevertheless, concurrent with these critiques of the disintegration of consistency and wholeness in Cubism, he both elaborated the decorative possibilities of Cubism and distilled a more purified austerity. The possible variations made room for humour, irony and high seriousness.

(V) WAR YEARS

From June to November 1914 Picasso lived in Avignon. At the outbreak of World War I in August, Braque and Derain were mobilized and Apollinaire applied for French citizenship and joined the artillery. Only Gris, a fellow Spaniard, remained from the Cubist circle. Although, unlike his French colleagues, Picasso was able to carry on painting without interruption, his work became more sombre during the war years as his life altered dramatically. Kahnweiler’s contract had lapsed on his departure from France, and in the autumn of 1914 Picasso’s work began to be sold by Léonce Rosenberg. He suffered deep loss with the death of Eva Gouel on 14 December 1915 but had a brief secret affair with Gaby Lespinasse in 1915–16. In March 1916 Apollinaire returned wounded from the front; although they renewed their friendship, Picasso began to frequent a new social circle, that of the Ballets Russes, with the encouragement of a young poet whom he had recently met, Jean Cocteau, whose admiration quickly approximated adulation.

QUATRE FEMMES NUES ET TÊTE SCULPTÉE (B. 219; BA. 424)

Etching, 1934, Signed in Pencil,

From the Total Edition of 310, Plate 82

From the Vollard Suite,

On Montval Laid Paper With the Vollard Watermark,

Printed by Lacourière, Paris, Published by

Vollard, Framed

Dimensions: Image: 222 by 313 mm, Sheet: 339 by 449 mm

Dimensions: Image: 222 by 313 mm, Sheet: 339 by 449 mm

FIGURE AT THE SEASIDE, 1931

ETCHING: 1,5 MARCH 1972

From 156 Series

Etching, Dry Point and Aquatint on Paper

Dimensions Unconfirmed: 370 x 500 mm

Collection: Tate

READING, 1932

FEMME NUE ASSISE ET TÊTES BARBUES (B. 216; BA.

416)

Aquatint, Scraper, Drypoint, and Etching, 1934,

Possibly Printed in 1939, a Proof Aside From the Total

Edition of 310,

Plate 25 From the Vollard Suite, on

Wove Paper,

Printed by Lacourière, Paris, Framed

Dimensions: Plate: 129 by 179 mm, Sheet: 224 by 317 mm 8

Dimensions: Plate: 129 by 179 mm, Sheet: 224 by 317 mm 8

STUDY FOR LES DEMOISELLES D’AVIGNON 1907

Oil on Canvas - 18.5 x 20.3 cm

Credit Line: Acquired through the

Lillie P. Bliss Bequest

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society , New York

THE VIOLATION SERIES

Suite Vollard 9 (Vollard Suite 9), 1931

Etching on Laid Paper

Dimensions: Image: 22,1 x 31,2 cm / Support: 34 x

44,5 cm

Category:Graphic Art

WOMAN WITH YELLOW HAIR,1931

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 100 x 81 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser

Collection,

Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978

© 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights

Society (ARS), New York

WOMAN

WITH YELLOW HAIR

One

year before Picasso painted the monumental still life Mandolin and

Guitar, Cubism’s

demise was announced during a Dada soiree

in Paris by an audience member who shouted that “Picasso [was] dead on the

field of battle”; the evening ended in a riot, which could be quelled only by

the arrival of the police. Picasso’s subsequent series of nine vibrantly

colored still lifes (1924–25), executed in a bold Synthetic Cubist style of

overlapping and contiguous forms, discredited such a judgment and asserted the

enduring value of the technique. But the artist was not simply resuscitating

his previous discoveries in creating this new work; the rounded, organic shapes

and saturated hues attest to his appreciation of contemporary developments in

Surrealist painting, particularly as evinced in the work of André Masson and

Joan Miró. The undulating lines, ornamental patterns, and broad chromatic

elements of Mandolin and Guitar foretell the emergence of a fully

evolved sensual, biomorphic style in Picasso’s art, which would soon celebrate

the presence of his new mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter.

When

Picasso met Marie-Thérèse on January 11, 1927 in front of Galeries Lafayette in

Paris, she was 17 years old. As he was married at the time and she only a

teenager, they were compelled to conceal their intense love affair. While their

illicit liaison was hidden from public view, its earliest years are documented,

albeit covertly, in Picasso’s work. Five still lifes painted during 1927—incorporating

the monograms “MT” and “MTP” as part of their compositions—cryptically announce

the entry of Marie-Thérèse into the artist’s life. By 1931 explicit references

to her fecund, supple body and blond tresses appear in harmonious, voluptuous

images such as Woman with Yellow Hair. Marie-Thérèse became a constant

theme; she was portrayed reading, gazing into a mirror, and, most often,

sleeping, which for Picasso was the most intimate of depictions.

The

abbreviated delineation of her profile—a continuous, arched line from forehead

to nose—became Picasso’s emblem for his subject, and appears in numerous

sculptures, prints, and paintings of his mistress. Rendered in a sweeping,

curvilinear style, this painting of graceful repose is not so much a portrait of

Marie-Thérèse the person as it is Picasso’s abstract, poetic homage to his

young muse.

https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/3445

HEAD OF A PACIFIST WARRIOR, 1951

Indian Ink on Paper

Dimensions: 50,5 x 60,5 cm

Category: Work on Paper, Drawing

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

CHILD WITH A SHOVEL

Mougins, 15 July and 14 November 1971 |

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 195 x 130 cm

Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso Para el Arte.

Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso Para el Arte.

On Temporary Deposit at the Museo Picasso Málaga

© FABA Photo: Marc Domage © Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

© FABA Photo: Marc Domage © Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

THE TABLE FROM SAINT MATOREL

Author: MaxJacob

August 1910, Published 1911

Etching From an Illustrated Book

with Four Etchings, One With Dry Point

Dimensions: Plate: 20 x 14.2 cm;

Sheet: 26.2 x 21.4 cm

Credit Line: Abby Aldrich

Rockefeller Fund

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

HEAD ( STUDY FOR LES DEMOISELLES

D’AVIGNON ) - 1906

Watercolor on Paper

Dimensions: 22.4 x 17.5 cm

Dimensions: 22.4 x 17.5 cm

Credit Line: The John S. Newberry

Collection

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

MAN WITH GUITAR

1915, published 1929

Engraving, Drypoint, Andaquatint

Dimensions: Plate: 15.5 x 11.5 cm;

Sheet (irreg.): 28.3 x 19.4 cm

Credit Line: Gift of Mr. and Mrs.

WalterBareiss

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

FIGURES BY THE SEA I, 1932

Oil and Black Chalk on Canvas

Dimensions: 130 x 97 cm

Category: Painting

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

FEUILLE D'ÉTUDES TECHNIQUES. NEUF TÊTES (B. 285; BA.

438)

Etching, 1934, Printed in 1961,

Baer's B.b of C, Stamped With the Artist's Signature

and

Inscribed in Pencil Epreuve d'artiste, One of 19 Recorded

Artist's

Proofs Aside From the Numbered Edition of 50,

On Greenish Laid Paper, Printed by Frélaut, Paris

Dimensions: Plate: 317 by 226 mm, Sheet: 525 by 395 mm

Dimensions: Plate: 317 by 226 mm, Sheet: 525 by 395 mm

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

MOTHER WITH DEAD CHILD (II).

POSTSCRIPT OF ‘’GUERNICA’’, 1937

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 130 x 195 cm

Painting

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

MOTHER WITH DEAD CHILD (II). POSTSCRIPT OF ‘’GUERNICA’’

The motif of the mother holding the

dead child is one of the most significant in Guernica, and this

image of motherhood was to become an obsession with Pablo Picasso, who

continued to depict it after the mural was completed. The pictures done once

the painting was finished, on June 4th 1937, are known as the

‘postscripts’ to Guernica, meaning work done in the painting’s wake

but still linked formally and conceptually to it, such as is the case with this

painting, Madre con niño muerto (II). Postscripto de «Guernica» (Mother

with Dead Child [II]. Postscript for “Guernica”, September 26th) or

in a subsequent development of the subject, in the numerous heads of weeping

women.

As in other Picasso artworks known

for their social content, in Madre con niño muerto (II) the

artist decided against the use of colour, in the strict sense of the term. The

choice to use monochrome could be the result, therefore, of a desire to

accentuate the abstract side of reality, resulting in the transformation of a

specific event into a universal archetype.

Paloma Esteban Leal

WEEPING WOMAN’S HEAD WITH HANDKERCHIEF (III).

POSTSCRIPT OF ‘’ GUERNICA ‘’,1937

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 92 x 73 cm

Category: Painting

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

WEEPING

WOMAN’S HEAD WITH HANDKERCHIEF (III).

POSTSCRIPT

OF ‘’ GUERNICA ‘’

One of the central motifs linked to Guernica are the figures known as the “weeping women”, inspired

in their physical appearance by Dora Maar. These portraits would be the

pictures Pablo Picasso redid most often once he had completed the great mural

on June 4th 1937. Picasso introduced at least three formal

variations to the compositions with regard to Guernica itself, the first being the tears that run down the

contorted female faces, which do not appear in the legendary work. The second

element, similarly absent from Guernica, is the handkerchief wiping the

tears and finally, alongside these two iconographic motifs, Picasso includes a

third formal variation; vivid colour, which becomes the protagonist of these

paintings, contrasting with the chromatic range of the great mural, executed,

as everybody knows, in whites, greys and blacks. The “Weeping Woman” was to

become a recurrent motif in Picasso’s output even up to the 1940s, creating a

link with the stylistic cycle begun by the painter in 1937, when he undertook

the renowned painting.

Paloma Esteban Leal

PIPE, GLASS, BOTTLE OF RUM - MARCH 1914

Cut-and-Pasted Colored Paper, Printed

Paper, and Painted Paper,

Pencil, and Gouache on Prepared Board

Dimensions: 40 x 52.7 cm

Credit Line: Gift of Mr. And Mrs.

Daniel Saidenberg

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

WOMAN WITH TAMBOURINE

Beginning of 1939, Published 1943

Etching and Aquatint

Dimensions: Plate: 66.7 x 51.2 cm;

Sheet: 76 x 56.5 cm

Credit Line: Acquired Through the

Lillie P. Bliss Bequest

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

STUDIO WITH PLASTER HEAD

Juan-les-Pins, summer 1925

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 97.9 x 131.1 cm

Dimensions: 97.9 x 131.1 cm

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

PAINTER WORKING, OBSERVED BY NUDE MODEL

Plate VIII from the Illustrated Book Le

Chef-D'Oeuvreinconnu

(Printexecuted 1927-1928) - Etching

Dimensions: Plate: 19.4 x 27.9 cm;

Page: 33 x 25.2 cm

Credit Line: The Louis E. Stern

Collection

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

FIGURES BY THE SEA I, 1932

Oil and Black Chalk on Canvas

Dimensions: 130 x 97 cm

Category: Painting

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

MAN WITH A HAT 1912

Cut-and-Pasted Colored Paper and

Printed Paper, Charcoal, and Ink on Paper

Dimensions: 62.2 x 47.3 cm

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

WOMAN WITH A GUITAR

Paris, March 1914

Oil, Sand, and Charcoal on Canvas

Dimensions: 115.5 x 47.5 cm

Dimensions: 115.5 x 47.5 cm

Credit Line: Gift of Mr. And Mrs. David

Rockefeller

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

CARD PLAYER

Paris, Winter 1913-14

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions 108 x 89.5 cm

Dimensions 108 x 89.5 cm

Credit Line: Acquired Through the

Lillie P. Bliss Bequest

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

NUDE WOMAN, STANDING 1912

Ink and Pencil on Paper -

Dimensions: 30.7 x 18.7 cm

Dimensions: 30.7 x 18.7 cm

Credit Line: Louise Reinhardt Smith

Bequest

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

HARLEQUIN AND WOMAN WITH NECKLACE 1917

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 200 cm.

Legacy of Baroness Eva Gourgaud in 1965

Centre Pompidou

SCULPTEURS, MODÈLES ET SCULPTURE (B. 149; BA. 301)

Etching, 1933, Printed in 1939,

From the Total Edition of 310, Plate 41 From

the Vollard Suite,

On Montval Laid Paper, Printed by Lacourière, Paris,

Published by Vollard, Paris

Dimensions: Plate: 194 by 267 mm, Sheet: 330 by 440 mm

Dimensions: Plate: 194 by 267 mm, Sheet: 330 by 440 mm

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

STILL LIFE 1912

STUDY OF PROFILES – DECEMBER

8, 1948)

Lithograph

Dimensions: Composition: 73.3 x 55 cm;

Sheet: 75 x 56.3 cm

Credit Line:Mrs. Bertram Smith Fund

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

THE

DEPARTURE - MAY 20, 1951

Lithograph

Dimensions:

Composition: 53.8 x 64.9 cm; Sheet: 53 x 64.9 cm

Credit

Line: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund

©

2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

PORTRAIT OF SYLVETTE DAVID, 1954

THE EMBRACE. III FROM THE VOLLARD SUITE

April 23, 1933, Printed 1939 - Drypoint

Dimensions: Plate: 29.6 x 36.5 cm;

Sheet: 34 x 45.1 cm

Credit Line: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller

Fund

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York

NUDE WOMAN IN A RED ARMCHAIR 1932

Oil Paint on Canvas

Dimensions Support: 1299 x 972 mm

Collection: Tate

RAPHAËL ET LA FORNARINA. XII: LE PAPE EST BOUCHE

BÉE DANS SON FAUTEUIL

(B. 1787; BA. 1804)

Etching, 1968, Signed in Pencil, a Proof Aside From

the Numbered Edition of 50,

Plate 307 From the 347 Series,

On Wove Paper, Printed by Crommelynck, Mougins

Dimensions: Plate: 148 by 209 mm, Sheet: 283 by 348 mm 11

Dimensions: Plate: 148 by 209 mm, Sheet: 283 by 348 mm 11

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

ON

THE BEACH, 1937

Oil, Conté Crayon & Chalk on Canvas

Dimensions: 129.1 x 194 cm

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Peggy Guggenheim

Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society

(ARS), New York

ON THE

BEACH

During

the early months of 1937 Pablo Picasso was responding powerfully to the Spanish Civil

War with the preparatory drawings for Guernica and with etchings such

as The Dream and Lie of Franco, an example of which is in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. However, in this period he also executed a group of

works that do not betray this preoccupation with political events. The subject

of On the Beach, also known as Girls with a Toy Boat, specifically

recalls Picasso’s Three Bathers of 1920. Painted at Le

Tremblay-sur-Mauldre near Versailles, On the Beach is one of several

paintings in which he returns to the ossified, volumetric forms in beach

environments that appeared in his works of the late 1920s and early

1930s. On the Beach can be compared with Henri Matisse’s Le Luxe, II, ca. 1907–08, in its simplified,

planar style and in the poses of the foreground figures. It is plausible that

the arcadian themes of his friendly rival Matisse would appeal to Picasso as an

alternative to the violent images of war he was conceiving at the time.

At

least two preparatory drawings have been identified for this work. In one

(Collection Musée Picasso, Paris), the male figure looming on the horizon has a

sinister appearance. In the other drawing (present whereabouts unknown),¹ as in

the finished version, his mien is softened and neutralized to correspond with

the features of the two female figures. The sense of impotent voyeurism

conveyed as he gazes at the fertile, exaggeratedly sexual “girls” calls to mind

the myth of Diana caught unaware at her bath.

https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/3449

PABLO PICASSO'S POSTERS

1.EARLY YEARS, TO 1905

Source: Oxford University Press

(I) SPAIN & PARIS

Picasso received his first lessons in 1888 from his father, José Ruiz

Blasco (1838–1913), a painter specializing in pictures of pigeons and doves,

and a teacher of drawing at the Escuela Provincial de Bellas Artes in Málaga.

It was Picasso’s father who first recognized and encouraged his aptitude for

art. His earliest preserved drawings, produced as a child of nine, display a

precocious grasp of naturalistic conventions. The imagery of his childhood and

teenage drawings reflects his father’s repertory, a fascination with the

bullfight (e.g. Bullfight, La Coruña, 2 Sept 1894; Paris, Mus. Picasso,

401) and conventional academic studies (e.g. Study of a Torso, after a

Plaster Cast, 1894–5; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 405).

In 1891 the family, including Picasso’s two younger sisters, moved to La

Coruña, on the Atlantic coast, where in 1892 Picasso enrolled in his father’s

classes in ornamental drawing at the Escuela de Bellas Artes before progressing

to drawing from figures and plaster casts and to painting from nature. In 1895

he produced about 15 oil portraits both of family friends and of socially

marginal types which sympathetically present the sitter, for example Girl

with Bare Feet (1895; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 2). He also experimented from

1894 with more biting caricatures and satirical sketches in manuscript

‘newspapers’ variously titled Azul (or Asul ) y

blanco and La Coruña (e.g. 16 Sept 1894; Paris, Mus. Picasso,

402), which emulated the subject-matter of popular political journals of the

time.

Picasso’s father changed teaching jobs again in 1895, this time moving to

the Escuela de Bellas Artes (known as La Lonja) in Barcelona. In September,

aged only 14, Picasso passed the examinations to enter the senior course in

classical art and still-life. During the next few years he began to assert his

independence, attending the academy only irregularly. He found a studio with a

friend, Manuel Pallarés, and began exhibiting his work. The First

Communion (1896; Barcelona, Mus. Picasso) and Science and Charity (1897;

Barcelona, Mus. Picasso), awarded a gold medal at the Exposición de Bellas

Artes in Málaga, were both characterized by a sharp delineation and tonal

modelling that contrasted with the light, boldly brushed handling in landscapes

of the same period, such as Mountain Landscape (c. 1896; Barcelona,

Mus. Picasso).

In autumn 1897 Picasso briefly attended the Academia Real de San Fernando

in Madrid, but he was critical of its teaching and instead studied the diverse

range of Old Master paintings in the Prado, where he copied a portrait of Philip

IV by Velázquez. With Pallarés he departed in June 1898 for the

village of Horta de Ebro (now Horta de San Juan). On his return to Barcelona in

February 1899 he began to frequent Els Quatre Gats (Cat.: The Four Cats), a

café that served as a meeting-place for the Catalan modernist movement. There

he became acquainted with a circle of artists and writers; the friendships that

most affected his development as an artist were with the painter Carles

Casagemas (1880–1901) and the poet Jaime Sabartés (1881–1968). Picasso quickly

established himself as provocateur among the younger

generation, taking account of Art Nouveau (especially in his graphic

work) and in his paintings evoking the fin-de-siècle Symbolism of

artists as diverse as Toulouse-Lautrec and Munch; it was through this milieu

that he also came to appreciate the work of El Greco.

Several major events in Picasso’s artistic maturation coincided with the

new century. In February 1900 he exhibited 150 drawings, mostly portraits, at

Els Quatre Gats, directly challenging his older colleague Ramón Casas; several

of these were published. A painting, Last Moments (destr.), was

selected for the Exposition Universelle in Paris, and in October he left with

Casagemas for Paris, where he met two dealers, Pedro Mañach and Berthe Weill,

to whom he sold works; Mañach also offered him a regular income in exchange for

paintings. Until 1904 Picasso moved restlessly between Spain and Paris. From

January to April 1901 he lived in Madrid where, in February, he received news

of Casagemas’s suicide. In response he produced several intense images of his

dead friend including the Death of Casagemas (summer 1901; Paris,

Mus. Picasso, 3) and a symbolically complex work, Evocation: The Burial of

Casagemas (1901; Paris, Mus. A. Mod. Ville Paris), which superimposed

allusions to the art of the past and in particular to El Greco’s Burial

of Count Orgaz (1586–8; Toledo, S Tomé). In Madrid, Picasso and the

Catalan writer Francisco de Asis Soler founded a review, Arte Joven, which

was modelled on the Barcelona publication Pél i Ploma but which ran

for only four issues. This period in Madrid, although brief, marked an

important turning-point in the development of Picasso’s identity; it was at

this time that he began signing his works Picasso rather than P. Ruiz Picasso

or P. R. Picasso as before, favouring his mother’s more distinctive and

uncommon surname.

Picasso’s second visit to Paris lasted from May 1901 to January 1902, and

the third from October 1902 to January 1903. During his third stay he shared

cramped quarters and a rare period of impoverishment with the poet Max Jacob,

whom he had met on his previous visit. In late June 1902, before the opening of

his exhibition at the Galerie Vollard, he sold 15 of the 64 works to be

displayed; most of these paintings, such as The Death of Casagemas,

employed bright hues and broken brushstrokes. The show was favourably reviewed

by Félicien Fagus in the Revue Blanche, and an exhibition of Picasso’s

pastels was held concurrently at the Sala Parés in Barcelona. He also

participated in two exhibitions at the Berthe Weill gallery in Paris in April

and November 1902.

(II) BLUE PERIOD

By the end of 1901, in works such as Self-portrait (late 1901; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 4), Picasso had adopted a predominantly blue palette and shed his motifs of their earlier sardonic social vision. From this time until 1904, known as the Blue Period, his imagery focused on outcasts, beggars and invalided prostitutes, the latter based on observations made at the prison of St Lazare in Paris. He produced his first sculptures: a modelled figure, Seated Woman (1901; see 1967 exh. cat., p. 50), and two bronze facial masks, Blind Singer and Head of a Picador with a Broken Nose (both 1903; see 1967 exh. cat., p. 51). One of the most important works of the period, however, was a painting, La Vie (1903; Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.), a complex Symbolist allegory that evolved through numerous sketches. From X-rays it is known to have been painted over Last Moments and to have undergone several revisions. Its synthesis and layering of references rule out a fixed reading. Autobiography is embedded in the male figure, which was begun as a self-portrait but later given the features of Casagemas; the iconically stiff composition, compressed space and enigmatic gestures, however, evoke a more general significance.

Picasso returned in April 1904 to Paris, where he settled in a studio at le Bateau-lavoir and soon surrounded himself with a ‘Parisian family’. From this time he made France his home. He was introduced to the poet and critic André Salmon by Max Jacob, and in the autumn he met Guillaume Apollinaire. He began a liaison at this time with Fernande Olivier, whose features were given to many of his female figures during the next few years. His first important etching, The Frugal Meal (1904; Geiser, 1933, no. 21), was typical of Blue Period paintings such as The Blind Man’s Meal (1903; New York, Met.) in its subject-matter of a gaunt, impoverished couple in spartan surroundings. The end of the Blue Period was marked by an exhibition in October 1904 at the Berthe Weill gallery of 12 works from the previous three years.

(III) ROSE PERIOD

By the end of 1904 both the colour schemes and subject-matter of Picasso’s paintings had brightened. His pictures began to be dominated by pink and flesh tints and by delicate drawing; although the works were less monochromatic than those that preceded them, this phase came to be labelled his Rose Period. A fascination with images of saltimbanques, harlequins and clowns may be linked both to frequent visits to the Cirque Médrano and to an identification with such characters as alter-egos, a legacy of the 19th century. Family of Saltimbanques (1905; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), which includes figures that have been identified as disguised portraits of Picasso and members of his circle, sums up his preoccupations during this time. The idea of a group of figures who appear alienated and unable to communicate with each other, placed in a flattened and disjunctive space, seems to have been derived from Manet’s Old Musician (1862; Washington, DC, N.G.A.). Details of more anecdotal subject-matter are visible in preliminary sketches and X-ray photographs, but these were eliminated in the course of painting. Picasso’s debt to late 19th-century Symbolism remains in evidence, here evoking a state of being rather than an allegorical allusion, as had been the case in La Vie.

(IV) SCHOORL

In summer 1905 Picasso visited the town of Schoorl in the Netherlands at the invitation of a writer, Tom Schilperoort. In the few paintings made by him during this month, such as Dutch Girl (Brisbane, Queensland A.G.), he began to introduce weightier figures, and the works that he produced in the autumn developed in gravity and opacity; figures viewed frontally and in strict profile impose an archaizing stylization on a classical simplicity, as in the slightly later La Toilette (1906; Buffalo, NY, Albright-Knox A.G.). Two of these works were purchased by Leo Stein and his sister Gertrude, who soon became two of Picasso’s most important patrons and frequent hosts to him at their weekly salons. The other major artist promoted by the Steins during this period was Henri Matisse, who with fellow painters made a sensation at the Salon d’Automne of 1905 as instigators of a new movement, Fauvism. The Fauvists’ use of bright, unmodulated colour was not immediately reflected in Picasso’s paintings, but the same Salon d’Automne included an Ingres retrospective, a room devoted to Cézanne and three paintings by Henri Rousseau; the work of each of these artists was to play an important role in the evolution of Picasso’s art.

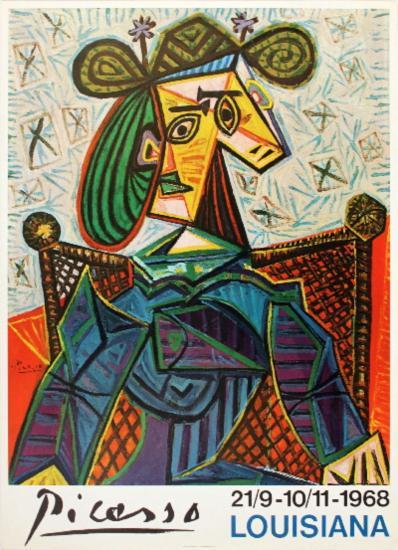

PABLO PICASSO'S POSTERS

PICASSO MUSEUM

PICASSO MUSEUM

PABLO PICASSO'S POSTERS

3. VARIATIONS OF STYLE,

CLASSICISM & THE THEATRE, 1916 - 1924

Source: Oxford University Press

(I) THEATRE DESIGNS, 1916 - 1922

Cocteau had already begun to plan the ballet that was to

become Parade by the time he met Picasso. In May 1916 he introduced

Picasso to Serge Diaghilev, impresario of the Ballets Russes, and by August

Picasso joined the enterprise. Picasso designed five complete ballet

productions by 1924, four of them for the Ballets Russes. Theatre design

encouraged his protean qualities and offered new challenges. It brought him

into contact with an expanded public and with the dancer Olga Koklova, whom he

married in July 1918, and professional associates in other fields. Each ballet

had different demands. The first, Parade (première 18 May 1917), and

the last, Mercure (première 18 June 1924), spawned the most

radical ideas. Parade evolved as a collaborative effort between

Picasso, Cocteau, the composer Erik Satie and the choreographer Léonide

Massine. The self-referentially theatrical scenario drawn from popular

entertainment afforded Picasso scope for his first major juxtaposition of Cubism (the décor) and naturalism

(the drop curtain) and his most comprehensive retrospective of imagery to date.

Large Cubist constructions were worn as body masks by several ‘Managers’.

Costumes for other characters employed found elements or refashioned the image

of the body in terms of art.

Later Ballets Russes projects adopted more unified, decorative use of

pictorial conventions and extended theatrical self-consciousness by displacing

the action to a stage within a stage. Diaghilev’s rejection of some sketches

gave Picasso a taste of the constrictions of commercial collaboration.

For Mercure, staged as part of the Soirées de Paris, an enterprise

sponsored by Etienne, Comte de Beaumont (1883–1956), he devised several moving

tableaux with ‘poses plastiques’ by Massine and music by

Satie. Mercure baited audience taste with a grotesque parody of

Classical mythology and seriously challenged conventional dance theatre, quite

literally absorbing the dancers into the visual conception of the stage.

Picasso also designed a set for Cocteau’s adaptation of Antigone (Dec

1922), his only work for the dramatic theatre during this period; the couturier

Coco Chanel (1883–1970) supplied the costumes.

Theatre design sanctioned Picasso’s use of style as a convention in the

painter’s vocabulary, as an element that could be donned and put aside like a

theatrical role, costume or mask. His contact with dance may also have

encouraged him to look more closely at bodily gesture and to explore an imagery

of motion. Encouraged by Koklova’s bourgeois aspirations, Picasso also assumed

a new way of life, moving into a more elegant apartment on the Rue La Boëtie in

November 1918, spending time in fashionable resorts, associating with

socialites and appearing in fancy dress costume as a matador at one of the

Comte de Beaumont’s parties.

(II) THREE MUSICIANS

In spite of the pressures on his time of both his theatre work and social

life, Picasso maintained his ambitions as a painter. Cubism continued to inform his

work, but his last large pronouncements of pure Synthetic Cubist order were two

versions of Three Musicians (1921; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A., and New

York, MOMA). The tightly interlocked, decoratively detailed and visually

punning Philadelphia version contrasts with the New York version’s more

enigmatic treatment set in a shallow spatial stage. The commedia

dell’arte characters, besides referring to Picasso’s past imagery and to

his current theatrical preoccupations, may also form part of a tribute to a

specific period in his life. According to Reff (1980), Harlequin represents

Picasso; Pierrot stands for Apollinaire, who had died on 9 November 1918; and

the monk-like figure is a substitute for Max Jacob, who went into seclusion at

the Benedictine abbey at St Benoît-sur-Loire in June 1921 and at whose baptism

in 1915 Picasso had acted as godfather.

(III) CLASSICISM IN THE 1920s

During the 1920s, concurrent with his continuing investigations of Cubism, Picasso devised a personal form of neo-classicism. Cocteau referred to such retrospective tendencies in the arts after World War I as a ‘rappel à l’ordre’; Picasso, however, had entertained such alternatives to Cubism as early as 1914. As a counterpart to Three Musicians he produced Three Women at the Spring, also in two versions (1921; New York, MOMA; and Paris, Mus. Picasso, 74), referring directly to Classical precedent in the physiognomy and garb of the figures and in the massively volumetric suggestion of carved high relief. Not all the classicizing works so directly evoke a golden age; monumental forms are sometimes clothed in modern dress, Classical gravity and order are sometimes unsettled (as in Still-life with Pitcher and Apples, 1919; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 64), and some works display a delicate linear lyricism or more elastic distortions. During this period Picasso also paraphrased and parodied work by Manet and the Le Nain brothers, for example The Happy Family, after Le Nain (1917–18; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 56). A soft-focus naturalism, sometimes alluding to Renoir or Corot, served for numerous portraits of Olga and of their son Paulo (b 4 Feb 1921).

Picasso travelled more extensively than before during these years. From February to April 1917 he was in Rome for the preparations of Parade and from there visited Naples and Pompeii. This direct experience of Italy and Roman Antiquity may have encouraged his classicizing investigations. In June and July of the same year he accompanied the Ballets Russes to Madrid and Barcelona and in May 1919 to London. He spent his summers in fashionable seaside towns: Biarritz, Saint-Raphaël, Juan-les-Pins, Dinard, Cap d’Antibes and Monte Carlo. While he lost his two closest friends, Apollinaire and Jacob, he made new acquaintances of a younger generation, such as fellow Spaniard Joan Miró in 1919 and the American Gerald Murphy. His friendship was also courted by poets such as Cocteau and the burgeoning Surrealists Louis Aragon and André Breton.

Despite the fluctuation in prices brought about by sales in 1921 and 1923 of the Uhde and Kahnweiler collections sequestered by the French government, Picasso’s reputation prospered. He showed pre-Cubist works in a joint exhibition with Matisse at the Galerie Paul Guillaume (Jan–Feb 1918) and had several exhibitions at Paul Rosenberg’s gallery (1919, 1920 and 1924); he also exhibited in Rome, Munich and New York. His illustrations were published in books by his poet friends, and the first monograph on his work, by Maurice Raynal, appeared in German in 1921 and in French translation in 1922.

© 2009 Oxford University Press

PABLO PICASSO'S POSTERS

WOMAN DRESSING HER HAIR

Royan, June 1940

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 130.1 x 97.1 cm

Dimensions: 130.1 x 97.1 cm

Credit Line: Louise Reinhardt Smith Bequest

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

THE SWIMMER, 1934

Black Chalk on Canvas

Dimensions: 182 x 216 cm

Painting

Entry date: 1988 (from the redistribution of the Museo

Español de Arte Contemporáneo [MEAC] collection)

THE

SWIMMER

The theme of bathers, and indeed beach scenes in general,

always held a great fascination for Pablo Picasso, who depicted them from

different approaches and in a succession of styles. However, both for the

atypicality of its iconography and the size and technique, La nageuse (The Swimmer) constitutes a special case within

Picasso’s universe of sea-themed figures and objects. Unlike most cases, in

this picture from 1934 Marie-Thérèse Walter primarily inspires fear. Her blond

hair has been transformed into a stiff plume, which seems to end in a

knifepoint, and the magnetism emanating from her squinting eyes is surpassed

only by the sensation of greed transmitted by her funnel-like mouth, waiting to

swallow a hypothetical prey. Brandishing her femininity – embodied in her heavy

breasts – like a banner, rather than enjoying the welcoming embrace of the

water, this ambiguous and terrifying character, with its huge stiff fin-like

hands, seems to be preparing for an imminent attack. Given the proximity of

armed conflict in his own country, it would not be too farfetched to believe

that Picasso conceived this ghostly apparition as a distant antecedent of Guernica itself.

Paloma Esteban Leal

BUSTE D'HOMME

WOMAN AT THE WINDOW 1952

Medium Aquatint and Dry Point on Paper

Dimensions: 902 x 635 mm

Collection: Tate

WEEPING WOMAN’S HEAD WITH HANDKERCHIEF (I).

POSTSCRIPT OF ‘’ GUERNICA ‘’, 1937

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 55 x 46 cm

Painting

Entry date: 1988 ( From the Redistribution of

the Museo Español de Arte Contemporáneo [MEAC]

Collection )

THE

CHARNEL HOUSE , 1944-45

Oil

and Charcoal on Canvas

Dimensions: 199.8 x 250.1 cm

Dimensions: 199.8 x 250.1 cm

Credit

Line: Mrs. Sam A. Lewisohn Bequest (by exchange), and Mrs. Marya Bernard Fund

in Memory of Her Husband Dr. Bernard Bernard, and Anonymous Funds

©

2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

THE CONVENT FROM SAINT MATOREL 1911

Author: MaxJacob

Etching From an Illustrated Book With

Four Etchings, One With Dry Point

Dimensions: Plate: 19.9 x 14.2 cm ;

Sheet (irreg.): 26.1 x 20.6 cm

Credit Line: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller

Fund

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

PORTRAIT OF JACQUELINE WITH GLOSSY HAIR

Feb. 16, 1962, Published 1963 - Linoleum Cut

Dimensions: Composition: 63.8 x 52.5

cm; Sheet: 75 x 61.9 cm

Credit Line: Gift of the Saidenberg

Gallery, New York

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

THREE STANDING NUDES, WITH SKETCHES OF

FACES

Plate IX From the Illustrated Book Le

Chef-D'Oeuvre In Connu

(Print executed 1927-1928) - Etching

Dimensions: Plate: 19.4 x 27.8 cm;

Page: 33 x 25.2 cm

Credit Line: The Louis E. Stern

Collection

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

ACCORDIONIST CERET 1911

STILL LIFE WITH BOTTLE OF MARC

1911, Published 1912 - Drypoint

Dimensions: Plate: 49.8 x 30.5 cm;

Sheet (irreg.): 62 x 42.4 cm

Credit Line: Acquired Through the

Lillie P. Bliss Bequest

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

PIPE, GLASS, BOTTLE OF VIEUX MARCH - PARIS 1914

WOMAN SITTING ON AN ARMCHAIR 1941

L'HOMME AU CHIEN (RUE SCHŒLCHER) (B. 28; BA. 39)

Etching, 1915, Signed in Red Crayon,

From the Total Edition of 102,

On Laid Japan Paper,

Published by Lucien Vollard-Marcel Lecomte, Paris,

Framed

Dimensions: Plate: 279 by 218 mm, Sheet: 458 by 290 mm

Dimensions: Plate: 279 by 218 mm, Sheet: 458 by 290 mm

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

VIOLIN

AND GRAPES 1912

Oil

on canvas - 61 x 50.8 cm

Credit

Line: Mrs. David M. LevyBequest

©

2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

THE SONG OF THE DEAD, 1948

Lithograph on paper

Dimensions: 42,5 x 32,5 cm

H.C. IV/XX

Category: Graphic Art

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

BOTTLE OF VIEUX MARC, GLASS, GUITAR & NEWSPAPER 1913

JACQUELINE IN A STRAW HAT, 1962

Linocut, Gouge and Linoleum Printed in Four Inks on Paper,

Linocut, Gouge and Linoleum Printed in Four Inks on Paper,

Dimensions: 63.8 x 53 cm

Museo Picasso Málaga. Purchased 2010

© Museo Picasso Málaga. Photo: Rafael Lobato

Museo Picasso Málaga. Purchased 2010

© Museo Picasso Málaga. Photo: Rafael Lobato

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

JACQUELINE IN

A STRAW HAT

The

starting point for the period defined as “late Picasso” is now considered to be

the early 1960s. While art history needs to define concrete periods, there were

still numerous other “Picassos” at that time. This is evident in the present

linocut of 1962 depicting Jacqueline, whom the artist had married the year

before and who would be his last partner in life. Linocut was one of Picasso’s

final techniques, which he first started to use in the 1950s for various

posters but which reached a new high point in 1958 with the tour de force of Portrait

of a Woman after Cranach the Younger.

Jacqueline

in a Straw Hat belongs to the

three most intensive years for the artist’s use of this technique, 1959 to

1962. The result was a vast body of work that astonished observers at the time,

not only for the combinations and superimpositions of colours but also for the

artist’s unorthodox working method. Picasso’s dealer Kahnweiler was amazed when

he saw his first works in this medium: “At first he limited himself to three or

four colours, now he’s doing prints with twelve colours on a single plate! It’s

diabolical” He has to anticipate the effect of each colour as there’s no going

back. I don’t know what name to give to this mental operation.” As he did with

ceramics, Picasso’s experiments with this new technique took it to its limits

in an all-encompassing approach that aimed to discover all its technical

procedures and to achieve the most difficult aspect, which is mentally

anticipating the final composition.

In Jacqueline

in a Straw Hat Picasso created the face using a

calligraphy identical to that seen in various drawings of the same day. This is

a work in which the artist constructed the face in the most economical way from

a combination of straight and curved lines and bright colours which contrast

strongly with the white background; a type of colouring and forms that to some

extent recall Joan Miró’s graphic language. Once again we have the classic

doubling of the face-mirror, which is very similar to the above-mentioned

drawings of this date. In fact, in that month of January 1962, Jacqueline’s

face would be Picasso’s primary focus, giving rise to various linocuts. This

month also saw the start of various celebrated series in the same technique

such as his versions of the Danaë and Le déjeuner sur l’herbe. This

“penultimate” Picasso breaks out at different moments, embarking on new

directions and new experiments which, as in this case, would remain unfinished

as he abandoned working in linocut around 1963 with the exception of a few

works created up to 1968.

Text:

Eduard Vallés

BACCHANALE II,1955

STUDY FOR A CONSTRUCTION 1912

Ink on Transparentized Paper

Dimensions: 17.1 x 12.7 cm

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

LIFE 1903

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 196.5 × 129.2 cm

Dimensions: 196.5 × 129.2 cm

Scala / Art Resource, NY / Picasso,

Pablo (1881-1973) © ARS, NY

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

GIRL WITH A MANDOLIN 1910

PIERROT & RED HARLEQUIN, STANDING -

C. 1920 - Stencil

Dimensions: Composition: 27.5 x 21.3

cm; Sheet: 30.5 x 23.8 cm

Credit Line: Lillie P. Bliss Collection

© 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

GUERNICA, 1937

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 349,3 x 776,6 cm

Painting

© Sucesión Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2017

GUERNICA

The

government of the Spanish Republic acquired the mural "Guernica" from

Picasso in 1937. When World War II broke out, the artist decided that the

painting should remain in the custody of New York's Museum of Modern Art for

safe keeping until the conflict ended. In 1958 Picasso extended the loan of the

painting to MoMA for an indefinite period, until such time that democracy had

been restored in Spain. The work finally returned to this country in 1981.

An accurate depiction of a cruel,

dramatic situation, Guernica was created to be part of the

Spanish Pavilion at the International Exposition in Paris in 1937. Pablo

Picasso’s motivation for painting the scene in this great work was the news of

the German aerial bombing of the Basque town whose name the piece bears, which

the artist had seen in the dramatic photographs published in various

periodicals, including the French newspaper L'Humanité. Despite that, neither the studies nor the finished picture

contain a single allusion to a specific event, constituting instead a generic

plea against the barbarity and terror of war. The huge picture is conceived as

a giant poster, testimony to the horror that the Spanish Civil War was causing

and a forewarning of what was to come in the Second World War. The muted

colours, the intensity of each and every one of the motifs and the way they are

articulated are all essential to the extreme tragedy of the scene, which would

become the emblem for all the devastating tragedies of modern society.

Guernica has attracted a number of controversial

interpretations, doubtless due in part to the deliberate use in the painting of

only greyish tones. Analysing the iconography in the painting, one Guernica scholar, Anthony Blunt, divides the protagonists of the

pyramidal composition into two groups, the first of which is made up of three

animals; the bull, the wounded horse and the winged bird that can just be made

out in the background on the left. The second group is made up of the human

beings, consisting of a dead soldier and a number of women: the one on the

upper right, holding a lamp and leaning through a window, the mother on the

left, wailing as she holds her dead child, the one rushing in from the right

and finally the one who is crying out to the heavens, her arms raised as a

house burns down behind her.

At this point it should be remembered that two

years earlier, in 1935, Picasso had done the etching Minotauromaquia, a synthetic work condensing into a single image all the

symbols of his cycle dedicated to the mythological creature, which stands as Guernica’s most direct relative.

Incidents in Picasso’s private life and the

political events afflicting Europe between the wars fused together in the

motifs the painter was using at the time, resulting both in Guernica itself and all the studies and ‘postscripts’, regarded

as among the most representative works of art of the 20th century.

Paloma Esteban Leal

http://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/collection/artwork/guernica

4. INTERACTIONS WITH SURREALISM,

1925 - 1935

Source: Oxford University Press

André Breton, the chief theorist

and promoter of Surrealism, claimed Picasso as ‘one of ours’ in his article ‘Le

Surréalisme et la peinture’, published in the fourth issue of Révolution

surréaliste (1925); the Demoiselles was first reproduced in the same issue. At

the first Surrealist group exhibition (Nov 1925) Picasso showed some of his Cubist

works. He never yielded completely to the concept of ‘psychic automatism in its pure state’ as

defined in the first Manifeste du surréalisme—poisson soluble (Paris, 1924),

but the movement did lead him to a new imagery and formal vocabulary for

emotional expression, releasing the violence, the psychic fears and the

eroticism that had been largely contained or sublimated since 1909. This shift

towards a more overt expressiveness was heralded by The Dance (1925; London,

Tate). Although it emerged from studies related to the ballet and was dependent

on Cubism for its conception of

space, the fusion of ritual and abandon in the imagery recalls the primitivism

of the Demoiselles and the elusive psychological resonances of

his Symbolist work. Resurrecting the memory of Casagemas, it also prefigures

Picasso’s ritually staged Crucifixion (1930; Paris, Mus.

Picasso, 122). Numerous images of women with devouring maws coincide with the

breakdown of Picasso’s marriage to Olga, while polymorphously eroticized

figures can be associated with a new liaison with Marie-Thérèse Walter, whom he

met in 1927, although she did not openly appear in his work until the 1930s.

Images of sexual intercourse between schematic stick figures or inflated

monsters, as in Figures by the Sea (12 Jan 1931; Paris, Mus.

Picasso, 131), suggest violent or ambivalent emotions.

(I) RENEWED INTEREST IN CLASSICISM

Surrealism not only rekindled

Picasso’s fascination with the primitive and the erotic but also encouraged a

conflation of his abiding interests in Classicism and the bullfight. The

mythical hybrid monster known as the Minotaur, half-man and half-bull, became a

favourite Surrealist image and the title of a Surrealist periodical, Minotaure,

whose first cover Picasso designed in 1933 (original collage, New York, MOMA).

Symbolizing both destructive and creative powers, the Minotaur served Picasso

as a new artistic identity. The complex etching Minotauromachy (1935;

Bloch, no. 288, I–V) provokes multiple narrative and symbolic associations,

ultimately stressing private meanings and never yielding a definite reading. In

another etching, Model and Surrealist Sculpture

(1933; Bloch 187), Picasso wittily confronts the Classical with the fantastic,

revealing his growing preoccupation with artistic practice and creativity. His

treatment of the theme of the artist’s studio in late Cubist paintings such

as Artist and Model (1928; New York, MOMA) and more

naturalistic etchings culminated in 1933–4 in the classical idyll of The

Sculptor’s Studio, a subsection of 46 of the 100 etchings gathered together

in 1937 but offered for sale as the Vollard Suite only in 1950. In these works

the artist is represented both as a contemplator and lover of his model/muse

and as an active practitioner; and, in contrast to Picasso’s own experience,

the making of art is depicted as a natural and unproblematic activity.

(II) EXPERIMENTS WITH DIFFERENT

MEDIA

During these years less

productive periods of painting alternated with outpourings of etchings and

sculptures. In addition to the Vollard Suite, Picasso illustrated

Balzac’s Le Chef d’oeuvre inconnu (Paris, 1931) for Vollard with

etchings produced in 1927, Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Lausanne,

1931) for Skira and an English translation of Lysistrata (New

York, 1934) for the Limited Editions Club. In spring 1926, having produced few

sculptures or reliefs since 1915, he executed a group of assemblages, on the theme of guitars, out of

cloth, nails and other materials, some protruding aggressively from the

surface. Austere and disturbing, they were succeeded in summer 1930 by

Surrealist-influenced bas-reliefs mounted on canvas and coated in sand, for

example Construction with Bather and Profile (1930; Paris, Mus.

Picasso, 125).

In 1921 Picasso had been

approached to design a monument to Apollinaire. Finally in 1928, with the

assistance of Julio González, a sculptor and trained metalworker, he realized

some maquettes made of metal rods such as Figure (1928; Paris,

Mus. Picasso, 264). This linear scaffolding became fleshed out with flattened

metal shapes in Woman in the Garden (1929–30; Paris, Mus. Picasso), a

homage to Marie-Thérèse as well as a proposal for the Apollinaire monument.

Although the submissions for the monument were rejected as too radical, the

renewed association with González, whom he had known since 1902, produced ten

collaborative sculptures over four years in Picasso’s most fruitful artistic

dialogue since the Cubist venture with Braque.

Unlike the frontal and opaque

earlier Cubist constructions, these metal sculptures proposed an open

three-dimensional structure that described and marked out a transparently

conceived space. Although their radicality portended much for the future of

20th-century sculpture, Picasso returned to a more Classicizing conception of

mass and volume in the large metamorphic bronze heads produced in 1931–2 at

Boisgeloup, for which Marie-Thérèse served as the inspiration; in works such

as Head of a Woman (1931–2; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 300) her features

were sometimes recast into a fetishized hermaphroditic image. In autumn 1935,

having produced no paintings since May, Picasso wrote some Surrealist automatic

poetry; this new venture marked the end of a decade of innovation, response to

younger artists, doubt, inner reliance and self-assessment.

(III) PERSONAL LIFE

The routine of Picasso’s private

life at this time was also punctuated by periods of instability. He continued

to spend the summer at seaside resorts, a habit he had established in the early

1920s. In 1933 and 1934 he took his family to Spain, visiting Barcelona (where

he saw the Romanesque art in the Museu d’Art de Catalunya in 1934) as well as

Madrid, the Escorial, Toledo and Saragossa. After considering and rejecting

divorce, Picasso separated from Olga in June 1935. On 5 October Marie-Thérèse

gave birth to a daughter, Maïa (María de la Concepción), named after Picasso’s

sister. Although by now regarded as a major artist, he began to receive

negative notices from those who perceived a decline in his more recent work. He

exhibited widely, winning the Carnegie International prize in October 1930 and

holding his first large retrospective at the Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, in

June 1932. The proliferation of publications on his work included the

monumental catalogue raisonné by Christian Zervos (first volume, 1932),

followed one year later by the first volume of Bernard Geiser’s Picasso: Peintre-graveur.

In July 1935, confronting fame and an apparent crisis in his work, Picasso

invited his old friend Sabartés to join him as his secretary and business

manager in November.

© 2009 Oxford University Press

5.WAR YEARS & LATER WORK,

1936 - 1973

Source: Oxford University Press

(I) SPANISH CIVIL WAR TO WORLD

WAR II

Events of the next years impelled

Picasso towards more public meanings for his hitherto personal symbols. On 14

July 1936 he contributed to Popular Front festivities in France. An enlargement

of a gouache, Composition with Minotaur (28

May 1936; Paris, Mus. Picasso), became the drop curtain for a performance of

Romain Rolland’s play Le 14 juillet; although this belonged to a series of

drawings on the Minotaur theme, the gestures and their context suggest a

politicized imagery. After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War on 18 July

1936, the Republican government appointed Picasso director of the Museo del

Prado. In January 1937 he etched The Dream and Lie of Franco I and II (Bloch,

nos 297 and 298) and wrote an accompanying poem to be sold for the benefit of

the Spanish Republic. The sequence of scenes depicts the General as a grotesque

polyp reminiscent of Alfred Jarry’s Père Ubu.

In January 1937 the Spanish

Republican government asked Picasso to paint a mural for the Spanish pavilion

at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, due to open in June. After a few

preliminary sketches relating to the theme of the artist’s studio, on 1 May

Picasso set to work on a vast painting, Guernica (oil on canvas, 3.51×7.82 m;

Madrid, Cent. Reina Sofía), finally spurred into action by the aerial bombing

by the Falangists of the Basque town of Guernica five days earlier. He then

worked intensively, producing more than 50 studies and making extensive

revisions on the large canvas. dora Maar, a Surrealist artist

and new companion whom he had met in 1936, photographed seven moments in the

production of the final work. Guernica was installed in Paris in mid-June;

redolent with political allusions, reportage and historical references, it has

since attracted numerous efforts at decipherment. Although a rich mine for

analysis, its success as painting or political statement has been obscured by

the fact that history has turned it into an icon. Its motifs produced numerous

progeny of a more personal nature, but responses to the worsening situation in

Spain and preparations for war in the rest of Europe are less in evidence; one

such work is Night Fishing at Antibes (Aug 1939; New York, MOMA), which adopts

jarring formal devices in a ritualized image of killing and detached

observation.

After the invasion of France by

the Germans in 1940, Picasso lived in his Paris studio on the Rue des

Grands-Augustins. Although watched by the German authorities, he was able to

work and even to cast some sculpture in bronze.

Skulls and death’s heads evoke the sombre mood, for example in Death’s Head

(1943; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 326). Similar imagery featured in paintings such as

Skull, Sea Urchins and Lamp on a Table (27 Nov 1946; Paris, Mus. Picasso, 198).

Le Désir attrapé par la queue (Paris, 1945), a play written by him in January

1941, deals with the privations of the occupation through the language of

poetic automatism. On 19 March 1944 it received a

private reading at the home of Michel and Louise Leiris; the participants, in

addition to the Leirises, included Albert Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul

Sartre and Dora Maar, and among the audience were the Braques, Brassaï, Jacques

Lacan and Sabartés.

Shortly after the Liberation on 5

October 1944 L’Humanité announced that Picasso had joined the French Communist

Party. The imagery of Massacre in Korea (1951; Paris, Mus.

Picasso) and the War and Peace murals (oil on

fibre board, each 4.7×10.2 m, 1952, installed 1954; Vallauris, Mus. N. Picasso)

was designed to win party approval. Picasso attended international peace

conferences in Warsaw (1948), Paris (1949) and Sheffield (1950), received the

Lenin Peace Prize (Nov 1950) and designed posters and a portrait of Stalin at

the party’s request. From August 1947 he made ceramics at the Madoura potteries

in Vallauris, partly motivated, it would seem, by political concerns. In

contrast to this humble medium, however, he also produced a considerable number

of bronze sculptures in the early 1950s, including some of his best-known works

in the medium such as She-goat (h. 1.21 m, 1950; Paris, Mus.

Picasso, 340) and Baboon and Young (h. 533 mm, 1951; New York, MOMA).

(II) PERSONAL LIFE, LATE 1930s TO

1953

Picasso’s emotional life during

this period continued to be turbulent. In the late 1930s he had liaisons with

both Marie-Thérèse Walter and Dora Maar, continuing his involvement with Maar

even after meeting a young painter, Françoise Gilot (b 1921), in 1943. Gilot

and Picasso began living together in 1946 and had two children, Claude (b 15

May 1947) and Paloma (b 19 April 1949). The years of Picasso’s most active

involvement with the Communist Party coincided with this relationship, but

Françoise left in 1953. By contrast with these unstable romantic entanglements,

Picasso had a profound and durable friendship from early 1936 with Paul Eluard,

a supporter of the left and a Communist Party member from 1942, which ended

only with the poet’s death in 1952. Before and after World War II Picasso spent

an increasing amount of time in the Mediterranean; with the purchase in the

summer of 1948 of La Galloise, a villa near Vallauris, he settled more

permanently in the south of France, although he retained residences and studios

in Paris. His international reputation had expanded and popularized during

these years, beginning in 1939 with the publication in Life magazine of

photographs of him taken by Brassaï in Paris and with the exhibition Picasso:

Forty Years of his Art at MOMA in New York. After the Liberation Picasso’s

marketability in the media was confirmed by a film, Visite à Picasso (1948),