THE SHARD DESIGN BY RENZO PIANO BUILDING WORKSHOP

The London Bridge Tower,

also known as the Shard, is a 72-storey, mixed-use tower located beside London

Bridge Station on the south bank of the river Thames. This project was a

response to the urban vision of London Mayor Ken Livingstone and to his policy

of encouraging high-density development at key transport nodes in London. This

sort of sustainable urban extension relies on the proximity of public

transportation, discourages car use and helps to reduce traffic congestion in

the city.

A mix of uses –

residential, offices and retail – creates a building that is in use 24 hours a

day. The slender, pyramidal form of the tower was determined by its suitability

to this mix: large floor plates at the bottom for offices; restaurants, public

spaces and a hotel located in the middle; private apartments at the top of the

building. The final floors accommodate a public viewing gallery, 240 m above

street level. This arrangement of functions also allows the tower to taper off

and disappear into the sky, a particularly important detail for RPBW given the

building’s prominence on the London skyline.

Eight sloping glass

facades, the “shards”, define the shape and visual quality of the tower,

fragmenting the scale of the building and reflecting the light in unpredictable

ways. Opening vents in the gaps or “fractures” between the shards, provide

natural ventilation to winter gardens.

The extra-white glass

used on the Shard gives the tower a lightness and a sensitivity to the changing

sky around it, the Shard’s colour and mood are constantly changing. It required

a particular technical solution to ensure the facade’s performance in terms of

controlling light and heat. A double-skin, naturally ventilated facade with

internal blinds that respond automatically to changes in light levels was

developed. The logic is very simple: external blinds are very effective in

keeping solar gain out of a building, but unprotected external blinds are not

appropriate for a tall building, hence the extra layer of glass facade on the

outside.

As part of the project, a

section of London Bridge Station’s concourse was also redeveloped and the

London Bridge Tower has been the stimulus for much of the regeneration of the

surrounding area, now known as the London Bridge quarter.

Consultants: Arup (

Structure & Service ) and more...

http://www.rpbw.com/project/58/london-bridge-tower/

INTERVIEW BETWEEN RENZO PIANO

& MARCUS FAIRS

Marcus Fairs: How did the Shard

project come about?

Renzo Piano: It was [Arup structural

engineer] Tony Fitzpatrick who called and said do you want to meet somebody?

And that somebody was [developer] Irvine Sellar [of Sellar Property

Group]. We met in Berlin. I was quite attracted by the idea of… not

really of making a tall building, but the idea of making a mixed-use tower – a

vertical city.

It was also clear that

this tower was sitting in the centre of a crossing system of different

transportation – trains, buses and all that. So it was typical of work we have

done in the past about brownfields – how to intensity life in the city. The

philosophy topping the expansion of the city by explosion and starting

implosion. Growth of the city from inside: filling the holes, filling the

industrial sites, railway sites. And then we started to work.

So that was the

beginning. Why we came up with this [the form of The Shard] is a bit more

difficult. The most important thing that attracted us was this idea of mixing

use, and the fact that it was sitting in a vital place of interchange. It

provided an excellent occasion to show that you could provide life in a city

without increasing the traffic – by using public transportation.

The first time I met

[then London mayor] Ken Livingstone in London it was clear Ken was happy about

this. It fell perfectly within his philosophy. So finally our philosophy, the

client’s philosophy, Ken’s philosophy and the city’s philosophy were coming

together. It was quite fortunate.

Then the next thing is if

you have to put mixed use – if you have to put together office space, hotel

space and residential space, you understand very quickly that for the office

you need that big platform [gesturing with hands], for the hotel you need that

big and for the houses you need that big. So if you need that that and that,

what is the shape you end up with?

In some ways it is

difficult to clarify between the conscious and the subconscious – between

rationality and instinct – but in some way this idea of something starting fat

and becoming small was a rational and instinctive process. Rational because it

made sense from the beginning. Instinctive because it became clear that the

only way to make something elegant was to not fill the sky – to make something

slim.

Was the shape a formal decision

or did it come through sketching?

No it also came by

sketching, and also by making models. I made a joke the first time Irvine came

to the office; I picked up in the workshop a shard – not of glass but of wood.

A splinter. I made a joke about it. actually it was quite immediate. If I’m not

wrong, even that day in Berlin – this may be part of Irvine Sellar mythology –

he reminded me last time that during the lunch I picked up a pencil and I

started sketching. We talked from the beginning that was quite wide here and

then less and less and less this idea of doing something that was probably

breaking the scale and coming up in this position, having an observation deck

here, certainly public space here, housing from here to here, hotel from here

to here, office here… this thing came very quickly.

As quickly as you just drew it?

Yeah, something like

that. But I don’t want to create a mythology. Then of course it became quite

evident from the first sketches that from that height up [indicates upper

levels of the building] you have quite a lot of wind and you are not going to

be able to use the space when you come down below 50sq m [per floor], so we

started to come up with the idea of the radiator [the finned heat-transfer

device that topped the building in early iterations but which has since been

replaced by a series of public viewing galleries].

It’s a glass building – and

glass buildings are not renowned for their energy efficiency.

As you know we are aiming

to save a lot of energy. Actually that is what we have done in Sydney;

the Aurora Place tower

that was finished five or six years ago actually saves one third of the energy

by the previous building there. There we used the breeze in the winter garden,

and chemicals in the glass. Glass technology has changed immensely.

We are working on

different things. One is that because it’s a mixed use, we have extra

production of heat from the offices that we can reuse in the residential part.

This is un-poetic but it is very intelligent.

The other thing is the

composition of the glass. We are working with double glass – actually triple

glass – with a space in between where we have lamellas – venetian blinds –

that cut heat gain from the sun. And when you don’t have sun – which happens in

London – you can lift up the lamella. They are inside the glass. Of course the

air between the two panes of glass heats up, but then we evacuate it and reuse

it.

So the composition of the

façade is part of the mystery, part of the story. And we are working on a chemical

glass with a composition… the blinds are better than tinted glass. You can see

them. At night they will disappear. There will be some facets that will

probably not even have lamella. It’s like the trunk of a tree, acting

differently all the way round, depending on how much sun it gets. The south

side will not be the same as the north.

We don’t use mirror glass

or tinted glass. We use new technology which is more subtle. The language of

the building will depend on this. We will use clear glass – low iron glass.

It’s also called extra white glass in England. This is very different from

regular glass, which is very green. If you use low iron glass you end up with

something that really is like a crystal. So depending on the day, the light and

the position of the sun, the building will look different. It will not look

like a massive glass meteorite - choom! - as many towers do. It’s going to be

more vibrant and changing.

How do you ensure that such a

tall building compliments, rather than damages, the city it sits in?

That’s a good question.

Towers usually have a very bad reputation - and normally a deserved reputation,

because they are normally a symbol of arrogance and power. In other words the

story towers normally tell are not very nice; not very subtle. They are just

about power and money. But the idea of a tower is not just a bad one. In

this case the desire to go up is not really to break any record – it is to

breathe fresh air. It is to go up to enjoy the atmosphere. So I think the first

point about serenity is more that the building is not struggling to be

powerful. It’s actually quite gentle. Especially as from the street the

building is not like that but is like that, and as a consequence it will

reflect the sky.

All this is about doing a building that is not arrogant. I don’t think arrogance will be a character of this building. I think its presence will be quite subtle. Sharp but subtle. This doesn’t mean you have to lose presence and intensity. I think the building will be intense – it’s not timid.

http://www.dezeen.com/2012/05/18/interview-renzo-piano-on-the-shard/

‘’ I always thought this

tower will be a sensor of the city, reflecting the mood. What the Shard does

for London is a list of things. I was aware of risks with the project when I

took it on, but the best things in life are always a little dangerous. ‘’

Renzo Piano

INTERVIEW BETWEEN RENZO PIANO

& MARCUS FAIRS

Marcus Fairs: In an interview a few

years ago you said “We have to have the confidence

to believe that we can create a tower that Londoners will come to respect as

they respect St Paul's. The power of Mammon created a beautiful city like

Sienna; this power can be put to good civic use, not just to make developers

rich.” Do you believe that?

Renzo Piano: I went

through this exercise a number of times including at a conference at the RIBA

when everybody was talking about adding towers to London. And I said I don’t

think London is a city of towers. I think Manhattan is a city of towers, it

makes sense there. I don’t think London is a city of towers and I don’t think

the only way of intensifying life in the city is by making towers. I don’t

think growth by implosion – rather than explosion at the periphery –

necessarily means building towers. The city of London, where the buildings

normally making the city are two or three floors, you can easily increase the

density of the city without making towers.

In London I don’t see

many many places where you can make towers. Also if you build a tower, you cast

a shadow. The funny thing is that here our shadow is cast on the river. We

don’t cast a shadow …

You are sitting above a

great hub of transportation. There are many things that make this building possible

there and not somewhere else. I think this is one of the few positions where

you can have towers.

But the tallest tower in

Europe?

First, Marcus, it will

only be the tallest for a few weeks! I’m joking. It’s not the highest because

we have been struggling to make it the highest. It’s not the highest when you

stop here. We didn’t try to beat any record.

But I think you are

touching something very important, which is the discussion about style,

the griffe, the recognisable gesture. I believe this is part of

the star system of architects but its not a good story for architecture because

it doesn’t celebrate architecture but celebrates the architects. I think in the

end is not good for architecture because in the end it limits the freedom. You

as an architect – let's assume you have a certain success; you are always

pushed to repeat yourself. It’s not just true for architects; it’s also true

for painters, writers, film makers. If you do something, people will ask you to

do it again. But this is not a good story; this is a lack of freedom.

Everybody talks about a

lack of freedom but probably the most difficult freedom to keep is not from

other people but from yourself. Freedom from other people is quite easy; if you

have a tough group of people working together as we are – honestly, we defend

our freedom quite well – but the most dangerous freedom to defend is the one

with yourself. Because you get used, you become self-referential, because

things go well. So you fall in the big trap, which is the one of recognisable

signature. The idea that you do things this way. So immediately people say that

is Pierre Cardin, Hermes or whatever. I’m not saying this to be a moralist; I

hate this idea of a repetitive gesture or a self-referential attitude; I hate

this idea of being trapped by the need to promote your griffe – your label – but at the same time I love the

idea of coherence. I love the idea that an architect has their own language. We

have to constantly fight against the temptation to repeat yourself.

You come from a family of

builders. How did this affect your architecture?

Architecture is not

construction. Architecture is art, but art vastly contaminated by many other

things. Contaminated in the best sense of the word – fed, fertilised by many

things. But I came to this attitude that architecture is art starting as a

builder.

And this was good because

it kept me away from academia when I was young. When you are young as an

architect you are always in danger of falling in to the trap of academia.

Academia is the attitude to make shape without knowing enough about the bottom

part of the iceberg. But if you become more humble – in 62 and 63, I was

sleeping more in the university of Milan than in my bed. It is true, I came

from a family of builders but I also came from a very strong social experience

of community life. Living with other people, changing the world, sleeping on

the bloody bench in the university. So this funny mix, this funny bouillabaisse

of emotion is very rich.

So it’s stupid to say

that coming from a family of builders was a good thing in itself because you

can learn later on, but it was good because it kept me away from formality.

From academia, from the easy pleasure of creating form.

Academia not just in

architecture but writing, painting, music – everything that is done without

rebellion. And when you are young it is very dangerous. When I was young

student, the Italian system was highly academic. Like in France. France now is

different; but don’t forget the École des Beaux-Arts has been spoiling

architects for ages. Creating pseudo-artistic architects. So in some way my

origins of a builder family kept me away from this. And it kept me away from

being too easily trapped in the pleasure of gesture.

The Centre Georges

Pompidou [the building Piano won at competition

with Richard Rogers in 1971, launching both of their careers, and which famously

features service pipes and ducts on the outside] could have been such a style

trap for you.

At first, people think

you will spend your entire life making pipes! And they ask you to make pipes.

This is also true for artists. If you take a great artist like Giacometti, for

example. Giacometti spent the last ten years repeating the same thing – because

he was asked to repeat the same thing. The poor guy – he was so nice and gentle

that he did. It was not nasty – he was not doing it to make money or whatever,

it was just a trap he fell in.

Architecture is by

definition a discipline – of course it is artistic, it is scientific, social

discipline – but it is a discipline where the adventurous side is very strong,

because every job is a new adventure. This is a completely different adventure

from making the Paul Klee museum in

Bern. It is completely different. How can you tell such a different story with

the same language? How can you worry about that? But you don’t have to worry if

you have an internal coherence. This will come anyway. But if you start

worrying then you fall in the trap. Instead of being free, you worry that is

not essential, which is “how will people recognise that it is mine”.

What is your internal

coherence?

Marcus, I don’t care but

people keep telling me that they recognise it. There was a guy who went to see

one of our buildings but he didn’t know it was one of ours. If there is

something there that is coherent… if you ask me what are the traces of this, I

think more than always using the same material, always the same rhythm, it is

more about a desire for lightness for example, for transparency, for vibration.

It’s not so different

from what we are trying to do with the New York Times[building

in New York, which features a curtain wall of ceramic tubes]. The poetic desire

behind this is similar – it’s about vibration, about becoming part of the

atmosphere, metamorphosis. Lightness, transparency, maybe tension between the

place and the built object.

There are certain characteristics.

I don’t think I should worry about it, but some critics tell us and they

normally talk about this – the emotion of a space being built up also by

immateriality. This is not my idea –[architecture critic] Rayner Banham

discussed the well-tempered environment. The idea that architecture is

sometimes built up by immateriality: light, transparency, long perspective,

vibration, colour, tension. I prefer to dig in this quarry rather in the

repetition of certain gestures.

Look, I was lucky enough to

be educated when I was a young architect in Milan to explore the cities, to put

my hand into science, utopia, to change the world. That’s the kind of thing you

do when you are young – rebellion. Don’t forget, rebellion, when you are young,

is the cheapest way to find yourself. However, how can you accept when you are

60 years old the humiliation of having a style. Of being grabbed by commercial

obligation. It’s a humiliation; it’s insulting. As an architect this is what

you have to aim [for]. This kind of freedom – maybe you will never change the

world but you have to believe you can otherwise you are lost.

So every time you get a

new job, the way you approach it is by saying ah… but how can you humiliate

yourself by saying no, no, no, forget it; first, how can we make ourselves

recognisable.

So if someone came to you and

said “I want a building with pipes on the outside”, what would you say?

I would laugh. You know

there is a moment in your life when people don’t come any more to say silly

things like that. We are in a very privileged position to be able to decide

what to do.

But a challenge like this

has a very deep root in the history of a city, in the history of science, so

there is a kind of utopia here. It’s not just a formal gesture. Even the little

idea of a vertical city, mixed use, intensify life without adding new cars. You

realise we have forty-seven cars in this building [The Shard]. The car park is

for forty-seven cars! Not 4,000. This is also because Ken Livingstone also said

don’t even add … just for handicapped people and that kind of use.

So there are many many

things here that are the invisible parts of architecture. It’s a bit like an

iceberg. The invisible part is what I call the social vision for a city, the

context and things like that. It’s very strongly there. Unless you do this,

architecture becomes very quickly an academic exercise; a formal exercise.

Many people claim the Centre

Georges Pompidou was the first building in the “high-tech” style. Was that

building a formal exercise?

In reality it is quite an

ironic building. It is not a real spaceship – it is a Jules Verne spaceship.

It’s really more a parody of technology than technology. It was just a direct

and quite innocent way to express the difference between the intimidating

cultural institutions like they normally were in the 60s and 70s - especially

in this city [Paris, where his studio is based] – and the modern building, very

open and a curious relationship with people. The idea was that it doesn’t

intimidate. We were young bad boys and we liked that.

But the Beaubourg is not

really the triumph of technology. It’s more about the joy of life. It’s a

rebellion.

Are you still rebellious?

Mmmmmm. in some ways yes. But you should not ask me, you should ask my wife.

http://www.dezeen.com/2012/05/18/interview-renzo-piano-on-the-shard/

‘’ The Shard is an icon,

a destination in itself. It represents a new generation of office building that

is more interested in effectiveness than efficiency. Its offices aren’t places

in which to sit and just crunch numbers. Instead, they’re places where

21st-century ‘knowledge’ workers can collaborate with each other, make

connections, think, socialise and use their creativity effectively. These

representatives of the information age – typically employed by media companies,

publishing houses, law firms etc – need a new type of working environment.

Fifty or 60 years ago, most offices were clerical factories, where people were

doing ‘process’ work – organising things, doing paperwork. Nowadays, we don’t

need to come to an office to find data or access phone lines; we can get our

emails on our mobiles, download data onto our tablets and laptops. Information

is up in the cloud. Organisations have to develop a new type of office

landscape and think about their workspace in radically different ways. ‘’

Professor Jeremy Myerson

RENZO PIANO BUILDING

WORKSHOP

Renzo Piano Building

Workshop company profile The Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW) is an

international architectural practice with offices in Paris and Genoa.

The Workshop is led by 13

partners, including founder and Pritzker Prize laureate, architect Renzo Piano.

The company permanently employs nearly 130 people. Our 90-plus architects are

from all around the world, each selected for their experience, enthusiasm and

calibre.

The company’s staff has

the expertise to provide full architectural design services, from concept

design stage to construction supervision. Our design skills also include

interior design, town planning and urban design, landscape design and

exhibition design services.

Since its formation in

1981, RPBW has successfully undertaken and completed over 120 projects across

Europe, North America, Australasia and East Asia. Among its best known works

are: the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas; the Kansai International Airport Terminal

Building in Osaka; the Kanak Cultural Center in New Caledonia; the Beyeler

Foundation in Basel; the Rome Auditorium; the Maison Hermès in Tokyo; the

Morgan Library and the New York Times Building in New York City; and the

California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. Recently completed works

include the Shard in London, and the new Whitney Museum in New York.

The quality of RPBW’s

work has been recognised by over 70 design awards, including major awards from

the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the Royal Institute of British

Architects (RIBA).

In all our work we aim to

address the specific features and potential of a particular situation,

embracing them into the project while responding to the requirements of the

program. We continue to push the limits of building technology – innovating,

refining and experimenting – to come up with the very best solution for each

situation.

Our method of working is

highly participatory, with clients, engineers and specialist consultants all

contributing from the beginning of a project and throughout the design process.

Our approach to design is

not strictly conventional and involves the use of physical models and

one-to-one scale mockups to help test and develop our proposed design concepts.

We also believe that the design process is not linear and that it requires

architects to think and draw on different scales at the same time, considering

each finished detail in the development of the overall design.

http://www.rpbw.com/en/architecture/3/the-firm/4/company-profile/

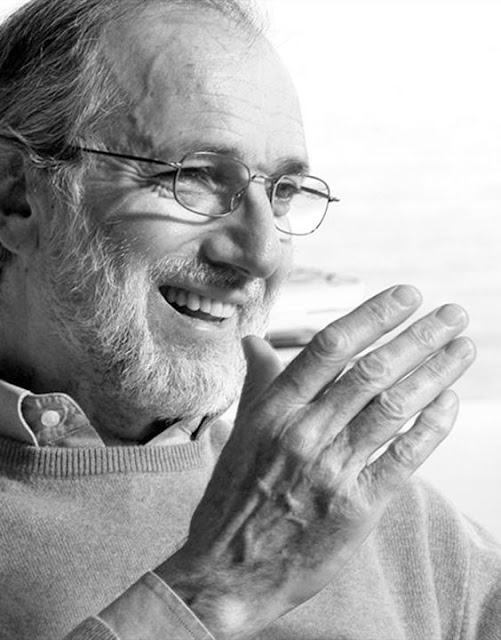

RENZO

PIANO

Chairman.

Founding Partner. Architect DPLG based at Paris Office.

Renzo

Piano was born in Genoa in 1937 into a family of builders.

While

studying at Politecnico of Milan University, he worked in the office of Franco

Albini.

In 1971,

he set up the “Piano & Rogers” office in London together with Richard

Rogers, with whom he won the competition for the Centre Pompidou. He

subsequently moved to Paris.

From the

early 1970s to the 1990s, he worked with the engineer Peter Rice, sharing the

Atelier Piano & Rice from 1977 to 1981.

In 1981,

the “Renzo Piano Building Workshop” was established, with 150 staff and offices

in Paris, Genoa, and New York.

He has

received numerous awards and recognitions among which: the Royal Gold Medal at

the RIBA in London (1989), the Kyoto Prize in Kyoto, Japan (1990), the Goodwill

Ambassador of UNESCO (1994), the Praemium Imperiale in Tokyo, Japan (1995), the

Pritzker Architecture Prize at the White House in Washington (1998), the Leone

d’oro alla Carriera in Venice (2000), the Gold Medal AIA in Washington (2008)

and the Sonning Prize in Copenhagen (2009).

Since

2004 he has also been working for the Renzo Piano Foundation, a non-profit

organization dedicated to the promotion of the architectural profession through

educational programs and educational activeities. The new headquarters was

established in Punta Nave (Genoa), in June 2008.

In

September 2013 Renzo Piano was appointed senator for life by the Italian

President Giorgio Napolitano and in May 2014 he received the Columbia University

Honorary Degree.

http://www.rpbw.com/en/architecture/3/the-firm/5/team/

.png)