THE PEGGY GUGGENHEIM COLLECTION: ARTS, ARTISTS & COLLECTOR

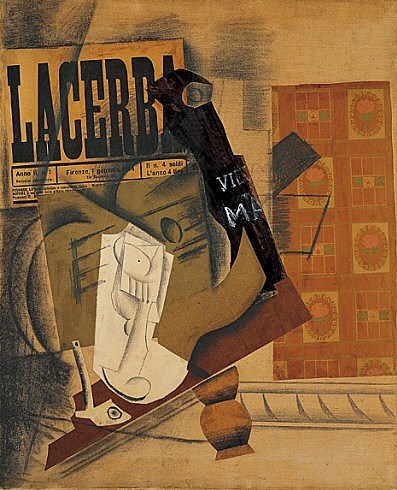

II. CUBISM, FUTURISM, AND ETHER PHYSICS IN THE EARLY

TWENTIETH CENTURY

BY LINDA DALRYMPLE HENDERSON

Returning to the question of Cubism and science leads

us to another key moment in the history of modernism’s engagement with the

invisible and imperceptible, which forms a leitmotif within this issue of Science

in Context. In order to determine the parameters of “what it was possible to imagine”

(Harrison 1993) for an artist like Picasso in the pre-World War I era, we need to

investigate the visual evidence of his Cubist works (e.g., the Portrait of

Kahnweiler of 1910 [fig. 2]) within the cultural field of avant-garde art writing, popular scientific

literature, and even occult sources in this period. Unfortunately, Picasso himself remains

an elusive subject, a painter’s painter who wrote no statements of his artistic ideas

in this period – in contrast to the Salon Cubists Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger,

Duchamp, or the Italian Futurists, such as Umberto Boccioni (see his 1913 drawing Muscular

Dynamism on the cover of this issue).49 Like Duchamp, whose extensive notes

for the Large Glass provide a useful guide to science as popularly known in prewar

Paris, Boccioni was actively engaged with contemporary science. As he queried in a

diary entry of 1907, “How,

where, when can I study all that chemistry and

physics?” (Coen 1988, 257).50 Thus,

chronicling Boccioni’s visual and verbal responses to

contemporary science serves as

a useful counterpoint to an examination of Picasso’s

Cubism, given the considerable

artistic and literary exchange between Paris and

Milan.51

For Picasso the case will necessarily be more circumstantial.

Yet an artist hardly needed to have had the specific interest in science of

Boccioni or Duchamp, since the exhilarating new ideas issuing from contemporary

science were readily available in popular journals, newspapers, and books as well as

responses to these phenomena in avant-garde literature.52 In addition, the presence

of the erudite poet Guillaume Apollinaire in Picasso’s circle and the record of his

library provide important clues to ideas that may have been present within Picasso’s

milieu, which also included the poet Max Jacob, the poet and critic Andre Salmon, and the

salon of Gertrude Stein. Before investigating Picasso, we need to

de-familiarize his Analytical Cubist works such as the Portrait of Kahnweiler, which

have come to look so natural to us in the last fifty years, hanging on the walls of collections of

modern art. Since mid-century we have tended to see Cubist painting through the

formalist art historical explanations of its evolution as a logical, internal

stylistic development, resulting from the lessons Picasso and his collaborator

Georges Braque learned from the art of Paul C´ezanne and African art.53 Hence,

from C´ezanne came the initial geometrical orientation and denial of one point

perspective and from African art, the powerfully simplified forms and, ultimately, the conceptual sign language that enabled Picasso to communicate

information about a sitter in the same way a caricaturist distills a subject’s

key characteristics. Yet, while the stylistic explanation is convincing for

early Cubist painting, by later 1909 or 1910, such radical changes occur that

artistic sources alone are no longer adequate. More recent scholarship has gone

a considerable way toward recovering Cubism’s larger cultural context,

including the fourth dimension, the philosophy of Henri Bergson, and

contemporary politics, but there are still basic questions posed by paintings

such as the Portrait of Kahnweiler. Why would

Picasso and Braque so stubbornly deny the solidity and boundaries of forms,

causing their sitters to dissolve into the surrounding space? The two painters

always considered themselves realist painters, with Picasso explaining later,

“I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them” (Gomez de la Serna 1929,

100). What can Picasso have been thinking or imagining about

the nature of reality?

Over two decades before the public in France first

heard of Einstein and Relativity Theory, the decade of the 1890s witnessed a series of

scientific discoveries that successively challenged conventional notions of matter

and space. These widely discussed developments included Wilhelm Conrad

R¨ontgen’s discovery of the X-ray in 1895, Henri Becquerel’s discovery of radioactivity

in 1896 (extended by the subsequent work of Marie and Pierre Curie as well as

Ernest Rutherford), J. J. Thomson’s identification of the electron in 1897, and the

subsequent establishment of wireless telegraphy based on the electro magnetic waves Heinrich

Hertz had identified in 1888.54

The existence of invisible realms just beyond the

reach of the human eye was no longer a matter of mystical or philosophical speculation; it

had been established empirically by science. Madame Curie asserted in regard to

radioactivity in 1904, “Once more we

are forced to recognize how limited is our direct

perception of the world around us”

(Curie 1904, 461).

Röntgen’s discovery of the X-ray caused the greatest

popular scientific sensation

before the explosion of the atomic bomb in 1945 (Badash

1979, 9). Rendering matter

transparent, X-rays made previously invisible forms

visible. Even more importantly, however, the X-ray definitively demonstrated

the inadequacy of the human eye, which detects only a small fraction (i.e., visible light) of

the much larger spectrum of vibrating electromagnetic waves then being defined.55 As the

astronomer Flammarion argued of X-rays in his 1900 book L’Inconnu, “[I]t

is unscientific to assert that realities are stopped by the limits of our knowledge and observation”

(Flammarion 1901, 14). On a practical level, X-rays were quickly adopted in medical

practice, and photography journals touted X-ray photography as the natural extension of

the amateur photographer’s activity. And the massive amount of popular literature

on the subject – including articles, books, songs, cartoons, poems, and cinema –

kept X-rays and their subsequent development in the news well into the first decade of

the new century (see Glasser 1934, chap. 6; Knight 1986; Henderson 1988).

X-rays offered a radically new way of seeing, breaking

down the barrier that the skin had always represented between outer and inner. That

same transparency and fluidity are evident in Picasso’s portrait of his dealer

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, a shift the sitter himself described around 1915 as “pierc[ing] the

closed form” or “skin” (Kahnweiler 1949, 10). Here was a new kind of light that allowed a

painter to go beyond the preoccupation of earlier artists with surface

appearances. Kahnweiler also noted that Picasso considered traditional modeling with visible

light and shade to be a dishonest “illusion” (Kahnweiler 1949, 11; Karmel 2003, 12).

Beyond the ubiquity of the X-ray in popular culture, Picasso was an amateur

photographer and would have encountered the advocacy of the new X-rays as “photography of the

invisible” in photography journals. Further, as John Richardson has documented,

Picasso’s companion, Fernande Olivier, was X-rayed in a hospital in January 1910.

And in 1917 Picasso queried in one of his sketchbooks, “Has anyone put a prism in front

of X-ray light?” (Richardson 1996, 158). All of this is not to suggest that Picasso’s

images derive from X-ray photographs, but rather that Cubist painting employs the general

model of penetrating vision as well as the characteristics of transparency and fluidity

suggested in X-ray images.56

Although, in contrast to Picasso’s static sitter,

Boccioni’s Muscular Dynamism depicts a figure in motion, the Futurist’s drawings and

paintings of this period exhibit a similar fluid relationship of figure and space. It was

Boccioni who had made the first published mention of X-rays in relation to avant-garde painting,

declaring in the 1910 “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting”: “Who can still

believe in the opacity of bodies . . . ? Why should we forget in our creations the doubled

power of our sight, capable of giving results analogous to the X-rays?” (Boccioni

1973, 28). Subsequently, he asserted in 1911, “What needs to be painted is not the visible

but what has heretofore been held to be invisible, that is, what the

clairvoyant painter sees” (Coen 1988, 239). Given the Futurists’ connections to activities in Paris,

Boccioni’s comments testify to the international currency of the new focus on the

invisible as well as occultism, in which Boccioni was deeply interested.57

The interpenetration of matter and space in the works

of both Picasso and Boccioni would have been encouraged equally in this period by

popular fascination with radioactivity. With the Curies’ isolation of two new

radioactive elements, polonium and radium, in l898 and Ernest Rutherford’s subsequent

formulation of the theory of radioactive decay in 1902–3, radioactivity captured

the attention of the general public (Badash 1979). Radioactive substances produced

yet another kind of invisible emissions – alpha, beta, and gamma “rays” (actually

particles in the case of the alpha and beta emissions) – and, in the process, actually

changed their chemical composition, releasing energy. In contrast to the traditional image

of matter as stable and constant, the continuous emission of particles by radioactive

substances suggested a vibrating realm of atomic matter in the process of

transformation. In his best-selling books, such as L’Evolution de la mati`ere (1905),

scientific popularizer Gustave Le Bon argued that all substances were radioactive and that matter was only

“a stable form of intra-atomic energy” in the gradual process of decaying back into

the ether of space around it (Le Bon 1905, 9; see also Le Bon 1906).58 Le Bon was a

friend of the philosopher Henri Bergson, whose import for the Cubists and

Boccioni has been well established.

Also, certain of Bergson’s views stand as counterparts

to Le Bon’s popularization of universal radioactivity (see, e.g., Antliff 1993;

Antliff and Leighten 2001, 80–93; Petrie 1974). In books such as Matter and

Memory of 1896 and Creative Evolution of 1907, Bergson argued that the essence of reality was flux

and that “all division of matter into independent bodies with absolutely determined

outlines is an artificial division” (Bergson 1988, 196).

Anyone could observe the phenomena of radioactivity at

home in the popular parlor toy, the spinthariscope, invented by Sir

William Crookes in 1903. Holding this tiny cylindrical instrument fitted with a

magnifying lens to the eye, a viewer could see the flashes of light produced when alpha

particles from a speck of radium struck the zinc-sulphide screen within. In

Picasso’s Portrait of Kahnweiler figure and ground are unified by a shimmering, vibratory texture

of brick-like Neo-Impressionist brushstrokes that likewise suggests atoms of matter

disassociating into the surrounding space, itself already filled with such particulate

emissions. Such images likewise deny the “independent bodies” Bergson had

rejected in favor of reality as continuity and flux. Boccioni’s paintings of this period, such as his

depiction of his mother entitled Matter of 1912 (Giovanni Mattioli Collection, Milan), are

likewise executed in a tapestry of discrete brushstrokes with which he deliberately

sought to convey the dematerialization of matter.59 In his writings Boccioni spoke of “the

electric theory of matter, according to which matter is only energy,” a contemporary theory

closely associated with the ether of space, which was also central to Boccioni’s

aesthetic (Boccioni 1975, 105).

Picasso need not have read Le Bon’s best-selling books

himself. His close compatriot Apollinaire owned a 1908 imprint of Le Bon’s L’Evolution

de la mati`ere as well

as Commandant Darget’s book on how to photograph

“fluido-magnetic” bodily emanations, such as the “Rayons V (Vitaux),” one of

the numerous varieties of emissions and rays thought to have been discovered in

the wake of X-rays.60 In the context of contemporary views of photography as a

revealer of the invisible, Picasso seems to have been fascinated by the intrusion

into his own photographs of “noise” suggestive of invisible phenomena.61 Like

Boccioni, Apollinaire was deeply interested in occultism, and he owned a number of

books dedicated personally to him by occultist Gaston Danville, including the

latter’s 1908 Magn´etisme et spiritisme (Boudar and D´ecaudin 1983, 52). In fact, occult

sources served in this period as an important means for the popularization of the new

physics, with texts on the practice of Magnetism or on other sort of emissions often

drawing on the latest developments in the physics of electromagnetism.62 Given the

Curies’ prominence as French cultural luminaries and with Apollinaire close at hand, Picasso

could hardly have been unaware of radioactivity’s fundamental reorientation of basic

conceptions of matter as well as its occult interpretations.

Along with radioactivity and Le Bon’s talk of matter

dematerializing into the ether, the recently discovered Hertzian waves of wireless

telegraphy (as well as X-rays) focused popular attention on the invisible, impalpable ether

of space. Space was not thought of as empty in this period, and the terms space and ether

of space are often synonymous in the written record. The longstanding concept of a

world-filling “aether” had returned to physics in the 1820s with Augustin Jean Fresnel’s

positing of a “luminiferous ether” as the necessary medium for the propagation of light

waves. By the 1860s James Clerk Maxwell and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) had

concluded that a material ether must also be the source of and vehicle for

electromagnetic fields.63 Early conceptions of the imponderable ether ranged from a thin elastic

jelly to a swirling fluid, and Kelvin suggested that atoms might well be

whirling vortices in the ether, akin to smoke rings.

In the later nineteenth and early twentieth century,

additional new functions were proposed for the ether, including its possible role as

the source of all matter, as in the “electric theory of matter” propounded by Joseph

Larmor and Sir Oliver Lodge and embraced in the writings of Boccioni and inWassily

Kandinsky’s 1911 U¨ ber das Geistige in der Kunst (see, e.g.,

Lodge 1904; Kandinsky 1973, 40).

In order to transmit vibrating electromagnetic waves,

including light, the mysterious ether required the rigidity of an elastic solid; at

the same time, it must allow the free motion of bodies through it and be rarefied enough to

flow through the interstices of even the densest matter. Le Bon noted the difficulty

of discussing this “phenomena without analogy” (Le Bon 1905, 88); not surprisingly,

the writing on the ether by both scientists and popularizers is filled with metaphor.

The passage of the immaterial ether through matter was compared to water flowing through a

sieve (Houston 1892, 489;

Houston 1909, 232); yet the ether as the very source

of matter made this relationship more complex. As science writer Robert Kennedy Duncan

declared of this “vast circumambient medium” in 1905: “Not only through

interstellar spaces, but through the world also, in all its manifold complexity,

through our own bodies; all lie not only encompassed in it but soaking in it as a sponge lies

soaked in water.” Raising a basic question repeatedly encountered in popular literature

in this period, Duncan declared, “How much we ourselves are matter and how much ether

is, in these days, a very moot question” (Duncan 1905, 5; see also, e.g., De

Launay 1908). The same year Le Bon in L’Evolution de la mati`ere emphasized

the ether’s elemental role in nature: The greater part of physical phenomena – light, heat,

radiant electricity, etc., are considered to have their seat in the ether. .

. . All the theoretical researches formulated on the constitution of atoms lead to the supposition

that it forms the material from which they are made. Although the inmost nature

of the ether is hardly suspected, its existence has forced itself upon us long

since, and appears to be more assured than that of matter itself. . .

. Its role has become of capital importance, and has not ceased to

increase with the progress of physics. The majority of phenomena would be

inexplicable without it.

(Le Bon 1905, 88–89)64

Historians of culture regularly treat Einstein’s 1905

Special Theory of Relativity (if not the 1887 Michelson-Morley experiment’s failure to

detect an “ether wind” resulting from the earth’s motion) as the death knell of the

ether. However, not only did the general public not hear of Einstein’s theories until

1919, the question of the existence of the ether was hotly debated among scientists

skeptical of Einstein’s theories during the 1910s and 1920s, with passionate defenses of the

ether being made in scientific and popular literature, including in France.65

Reflecting the mood of the ether’s adherents, Sir J. J. Thomson declared in his Presidential Address

before the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1909, “The ether is

not a fantastic creation of the speculative philosopher; it is as essential to us as

the air we breathe. . . . The study of this all-pervading

substance is perhaps the most fascinating duty of the physicist” (Thomson 1910,

15). Lodge certainly took that position, and his own BAAS Presidential Address,

published as Continuity in 1913, along with his 1909 The

Ether of Space and countless popular articles, kept the ether in the

spotlight in England and the United States, as well as in France. In Einstein’s

Germany the ether also continued to be championed in the 1910s by scientists

such as Gustav Mie, for whose electromagnetic theory of matter it was

central.66 Even with the ultimate scientific triumph of Relativity Theory sans

ether, the concept possessed such a powerful grip on the cultural imagination

that it lasted well into the 1920s and beyond.67

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century the

ether was the ultimate sign of continuity and signified a realm of continuous

cohesion and diffusion, materialization and dematerialization, coursed through by forces and

vibrating waves. Two later statements by Picassso are remarkably suggestive of

this insubstantial realm. Speaking of his paintings of the period 1910–1912 he told

curator William Rubin, “It’s not a reality you can take in your hand. It’s more like

perfume – in front of you, behind you, to the sides. The scent is everywhere, but you don’t

quite know where it comes from”

(Rubin 1972, 72). Some years earlier he had described

his portrait of Kahnweiler to Francoise Gilot in similar terms: “In its original

form it looked to me as though it were about to go up in smoke. But when I paint smoke,

I want you to be able to drive a nail into it. So I added the attributes – a

suggestion of the eyes, the wave in the hair, an ear lobe, the clasped hands – and now you

can” (Gilot and Lake 1964, 73). Did Picasso resort to such language because the

ether was no longer in common parlance as it had been? Significantly, the

association of the ether with smells such as perfume appears in a contemporary text, Emile

Durkheim’s The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life of 1912.

In discussing the powers of collective representations to take on “properties that do not exist in them,” Durkheim

concedes that sensations of smell, taste, and sight “do express the properties of

particular material or movements of the ether that really do have their origin in the bodies

we perceive as being fragrant, tasty, or colorful” (Durkheim 1995, 229).

The

ether is probably the major lacuna in scholars’ understanding of the early twentieth

century worldview – both scientific and occult – and, hence, its importance for

modernism in general. We need to be alert to its presence in writing of the period,

although as in the Durkheim example, it may simply appear as a commonplace reference.

Seen as both an ancient and a modern concept, the ether figured prominently in

occultism, and there achieved another kind of ubiquity. Apollinaire himself

responded to Theosophist Madame Blavatsky’s writing on the subject, echoing her

in a 1915 letter: “Is not every part of the material universe – including the

immaterial ether – a microcosm?” (quoted in Henderson 1986, 228). The ether,

along with Bergson’s philosophy, figures in Apollinaire’s fellow poet Jules

Romains’s theory of collective consciousness, which he termed Unanimism (see,

e.g., Martin 1969; Antliff and Leighten 2001, 93–95). In his 1908 prose

poem La Vie Unanime Romains celebrated the

experience of immersion in a vibrating, energyfilled ether on a Paris street.

The section of the poem titled “Dynamism,” which also speaks of “rays that

cannot be seen to vibrate,” begins with the epigram “The present

vibrates” and includes this passage: “The current/crowd, which struggles to

pass through/And gets hooked on the hedges of molecules, bleeds. The ripples of

ether part, [vibrating] with excitement” (Romains [1913], 79). The Salon

Cubists circle was close to Romains, and it has been argued that the presence

of smoke in their paintings was an allusion to Unanimism’s celebration of urban

experience, an idea that takes on new significance in relation to the ether

(Sund 1984).

The

ether was also at the heart of Boccioni’s artistic theory. At the conclusion of his

1914 treatise Pittura scultura futuriste Boccioni reveals the

formative role of the ether as ultimate sign of continuity in his conception of

the 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in

Space (fig. 3), for which Muscular Dynamism is a

study (Henderson 2002, 133–38). Believing that “solid bodies are only

atmosphere condensed,” Boccioni here creates a remarkable image of successive

muscular displacements that deny the boundaries of the body and leave traces or

imprints on the surrounding ether, suggesting “ether drag.” In his treatise

Boccioni specifically equates the “materialization of the ethereal fluid, the

imponderable” with “the unique form of continuity in space” (Boccioni 1975,

104). In the end, Muscular Dynamism, with its continuous

interpenetration of figure and space, may be even more successful as a

representation of the fluid continuity suggested by the ether (cover

illustration).

Boccioni

also related Unique Forms of Continuity in Space to the

spatial fourth dimension.

He appears to have thought of the sculpture alternatively as a four dimensional

entity passing through three-dimensional space and registering a succession of

different appearances – “a continuous projection of forces and forms intuited in

their infinite unfolding” (Boccioni 1975, 73). In defining a dynamic fourth

dimension for Futurism in his 1914 treatise, Boccioni was claiming the fourth

dimension for Futurism and reacting to the prominent role the spatial fourth

dimension played in Cubist theory.

In

contrast to later interpretations that attempted to tie Picasso’s Cubism and Apollinaire’s

criticism to the temporal fourth dimension of Einstein’s space-time world, Cubism’s

fourth dimension basically signified a suprasensible spatial dimension that might

hold a truth higher than that of visible reality.68 With its roots in n-dimensional geometry

and with significations ranging from geometry and science to philosophy, mysticism,

and occultism, the fourth dimension generated a huge amount of popular literature

in Europe and the United States. In tandem with the scientific issues discussed above,

the possible existence of an additional dimension of space would certainly have encouraged

Picasso’s bold pictorial invention. In the Portrait of Kahnweiler,

for example, the

geometrical faceting of objects suggests a more complex reality beyond immediate perception.

Picasso’s painting, in fact, shares with contemporary geometrical diagrams of

four-dimensional figures differently shaded angular components in ambiguous

spatial relationships

as well as a sense of shifting views of an object fused into one (fig. 4).

Ultimately,

the interpenetration of form and space – derived in large part from contemporary

scientific ideas – denies the possibility of reading the painting’s space as

three-dimensional.69

Discussions

of Picasso and the fourth dimension have hinged on the presence in his circle

of the insurance actuary Maurice Princet as well as Apollinaire’s declaration

in his Les

Peintres Cubistes that the fourth dimension was part of the “language of

the modern studios”

(Apollinaire 1944, 12). According to Apollinaire’s text, the fourth dimension offered

artists a rationale for distorting or deforming objects according to a higher law and

for rejecting three-dimensional, one-point perspective, which now seemed quite

irrelevant (Apollinaire 1944, 12; Henderson 1983, 75–89). In their 1912 book Du

Cubisme Metzinger

and Gleizes also discussed Cubism’s new mobile perspectives in

relation to Henri Poincar´e’s advocacy of perception using senses other than

vision, i.e.,

tactile and motor sensations, and his idea that “motor space would have as many dimensions

as we have muscles” (Poincar´e 1902, 72–73).70

Poincar´e

and Princet are crucial figures for Arthur Miller in his recent book Einstein,

Picasso: Space, Time and the Beauty That Causes Havoc. In

contrast to the numerous

authors who have attempted to find direct links or correlations between Picasso

and Einstein, Miller explores the “parallel biographies” of the two, arguing for

their common sources in the figure of Henri Poincar´e and the field of four

dimensional geometry (via Minkowski and Poincar´e for Einstein, via Princet for

Picasso).71 Nonetheless, Miller’s title still evokes for the potential reader

the myth that some

historical link existed between these cultural icons. As Duchamp observed in a 1967

interview, “The public always needs a banner; whether it be Picasso, Einstein, or some

other” (Cabanne [1967] 1971, 26). From the vantage point of the 1960s, Duchamp

was summing up a phenomenon he had observed developing since the

1920s:

the emergence of the perception of Picasso as the modern

artist and Einstein as

the scientist

of the twentieth century.72 Duchamp was an especially sensitive witness to

this,

since he knew personally that the art world of prewar Paris – including Cubism –

had

involved a variety of artists, including himself, and that the science in

question had

not

been Einstein’s.

Along

with Giedion’s 1941 Space, Time, and Architecture,

Apollinaire’s Les Peintres Cubistes text on

the fourth dimension played a definitive role in the emergence of the Cubism-Relativity

myth in New York in the 1940s. Giedion had cited Apollinaire’s discussion

of the fourth dimension and identified it as time, even though the poet repeatedly

referred to space (Giedion 1941, 357; Apollinaire 1944, 12). When The Cubist

Painters was

published in George Wittenborn’s “Documents of Modern Art” series

in 1944, its readers could easily have drawn a similar conclusion. Reflecting the

goal of Wittenborn and series editor Robert Motherwell to establish modern art’s legitimacy,

the books of the series bore on the back cover a text emphasizing that modern

art “assimilat[ed] the ideas and morphology of the twentieth century” and was

“the expression of our own historical epoch” (Apollinaire

1944, back cover; italics mine).

Here the stage was set for what became the classic confusion between Cubism then and

science now. Kepes’ references to space-time in his Language

of Vision of the same

year – along with Moholy-Nagy’s even more influential celebration of Einstein and

space-time as basic to understanding of modern life and art in his 1947 Vision

in Motion – only

exacerbated the situation.

By the

1940s both the spatial fourth dimension and ether physics had faded from popular

consciousness, occluded by Einstein and Relativity Theory. Largely forgotten

were the scientific heroes of the pre-World War I era in France: the Curies,

Poincar´e, and

science popularizer Gustave Le Bon, as well as R¨ontgen, Rutherford, Lodge, and Crookes.

Lodge and Crookes, along with Flammarion – with their openness to the occult

and involvement in the Society for Psychical Research – are pointed reminders of the

wider range of activities that were often classed as “science” in the late nineteenth and the

early twentieth century. Occultists regularly drew on the latest science to support

their causes, particularly in the linkages regularly made between X-rays and

spirit photography, radioactivity and alchemy, telegraphy and telepathy, and, as noted

earlier, electromagnetism and Magnetism.73 Such analogies were also drawn from

the side of science, as in Crookes’ prominent declaration in his 1898

Presidential Address

before the British Association for the Advancement of Science that “ether vibrations

have powers and attributes equal to any demand – even to the transmission of

thought” (Crookes 1899, 31).

That

capability of vibratory thought transfer attributed to the ether was vital to the art

theory of the painters Kandinsky and Frantiˇsek Kupka, who conceived their abstract

canvases as the source of vibrations meant to resonate in a viewer (see, e.g.,

Henderson

2002).74 Similarly, the poet Ezra Pound responded to the theme of ethereal telegraphy/telepathy,

comparing artists and poets to antennae “on the watch for new emotions,

new vibrations sensible to faculties as yet ill understood” (Pound 1912, 500). As in

the case of these modernists – along with the writings of Cubists, Futurists,

and

Duchamp

– the operative words that emerge from analyzing early twentieth-century cultural

discourse are not space-time and relativity, but

rather terms such as invisible, energy, ether, vibration,

and fourth dimension. Late classical ether physics – not relativity

theory – was the armature of the cultural matrix that stimulated the

imaginations of modern artists and writers before the later 1910s and 1920s.

Scholars of early modernism in general will surely benefit by turning their

attention to this long-eclipsed, but vitally important, moment in the history

of science and culture. “Sifted science will do your arts good,” James Joyce

declared in Finnegans Wake ( Joyce 1959, 440), and, as this

issue of Science in Context demonstrates, many modern artists

clearly agreed.75

JOSEF ALBERS

HOMAGE TO THE SQUARE R III A-I, 1970

HOMAGE TO THE SQUARE R III A-I, 1970

Oil on Masonite

Dimensions: 81.3 x 81.3 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation,

In Honor of Philip Rylands For his Continued Commitment

to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection 97.4556

© Josef Albers, by SIAE 2008

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation,

In Honor of Philip Rylands For his Continued Commitment

to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection 97.4556

© Josef Albers, by SIAE 2008

HENRI LAURENS (1885 – 1954)

HEAD OF

YOUNG GIRL 1920, CAST 1959

Terracotta

Dimensions:13 1/2 x 6 1/2 inches (34.2 x 16.5 cm)

The

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Henri

Laurens, who associated closely with the avant-garde painters of his

native Paris, worked in a Cubist idiom from 1915. In about 1920 he turned from

the production of bas-reliefs and frontalized constructions to the execution of

more classically ordered, freestanding sculptures. Head of a Young

Girl may have appeared originally as a drawing. However, in this bust

Laurens expresses Cubist painting principles in essentially sculptural terms.

The tilted surfaces and geometric volumes of the sculpture interpenetrate to

constitute a compact whole. Circling the piece, the viewer perceives

dramatically different aspects of the head, which provide a variety of visual

experiences unexpected in a form so schematically reduced.

The structuring planes of one side of the head are

broad and unadorned; its edges and planar junctures form strong, uninterrupted

curves and straight lines. The other side is articulated with detail; its

jagged, hewn contour describing hair contrasts rhythmically with the sweeping

curve of the opposite cheek. Laurens slices into the polyhedron that determines

the facial planes to describe nose, upper lip, and chin at one stroke. The

subtle modeling, particularly of the almond eye and simplified mouth, produces

nuanced relations of light and shadow. Despite the geometric clarity of

structure, the delicacy of the young girl’s features and her self-contained

pose create a gentle, meditative quality.

Lucy Flint

SALVADOR

DALI (1904 – 1989)

BIRTH

OF LIQUID DESIRES, 1931 - 1932

Oil and

Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 37 7/8 x 44 1/4 inches (96.1 x 112.3 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Credit

Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation/

Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York

Movement: Surrealism

By the time Salvador Dalí joined the Surrealist group

in 1929, he had formulated his “paranoid-critical” approach to art, which

consisted in conveying his deepest psychological conflicts to the viewer in the

hopes of eliciting an empathetic response. He embodied this theoretical

approach in a fastidiously detailed painting style. One of his hallucinatory

obsessions was the legend of William Tell, which represented for him the

archetypal theme of paternal assault.¹ The subject occurs frequently in his

paintings from 1929, when he entered into a liaison with Gala Eluard, his

future wife, against his father’s wishes. Dalí felt an acute sense of rejection

during the early 1930s because of his father’s attitude toward him.

Here father, son, and perhaps mother seem to be fused

in the grotesque dream-image of the hermaphroditic creature at center. William

Tell’s apple is replaced by a loaf of bread, with attendant castration

symbolism. (Elsewhere Dalí uses a lamb chop to suggest his father’s

cannibalistic impulses.) Out of the bread arises a lugubrious cloud vision

inspired by the imagery of Arnold Böcklin. In one of the recesses of this cloud

is an enigmatic inscription in French: “Consigne: gâcher l’ardoise totale?”

Reference to the remote past seems to be made in the

two forlorn figures shown in the distant left background, which may convey

Dalí’s memory of the fond communion of father and child. The infinite expanse

of landscape recalls Yves

Tanguy’s work of the 1920s. The biomorphic structure dominating the

composition suggests at once a violin, the weathered rock formations of Port

Lligat on the eastern coast of Spain, the architecture of the Catalan visionary

Antoni Gaudí, the sculpture of Jean

Arp, a prehistoric monster, and an artist’s palette. The form has an

antecedent in Dalí’s own work in the gigantic vision of his mother in The

Enigma of Desire of 1929. The repressed, guilty desire of the central

figure is indicated by its attitude of both protestation and arousal toward the

forbidden flower-headed woman (presumably Gala). The shadow darkening the scene

is cast by an object outside the picture and may represent the father’s

threatening presence, or a more general prescience of doom, the advance of age,

or the extinction of life.

Lucy Flint

SALVADOR DALI

UNTITLED, 1931

Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 27.2 x 35 cm

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 99

© Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, by SIAE 2008

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 99

© Salvador Dalí, Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, by SIAE 2008

ALEXANDER

CALDER

THE COW, 1971

Painted Steel

Painted Steel

Dimensions: 304.8 x 360.7 x 248.9 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and Rudolph B.

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and Rudolph B.

Schulhof

Collection, bequest of Hannelore B. Schulhof, 2012

© 2014 Calder Foundation, New York / SIAE, Rome, all rights reserved.

© 2014 Calder Foundation, New York / SIAE, Rome, all rights reserved.

CALDER

® is a registered trademark of Calder Foundation, NY.

ALEXANDER CALDER

ARC OF PETALS, 1941

Painted and Unpainted Sheet Aluminum, Iron Wire

Painted and Unpainted Sheet Aluminum, Iron Wire

Dimensions: Approximately 214 cm high

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 137

© 2014 Calder Foundation, New York / SIAE, Rome, all Rights Reserved.

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 137

© 2014 Calder Foundation, New York / SIAE, Rome, all Rights Reserved.

CALDER ® is a Registered Trademark of Calder Foundation, NY.

ALEXANDER

CALDER

RED

DISC, WHITE DOTS ON BLACK,1960

Painted Sheet Metal, Metal Rods and Steel Wire

Painted Sheet Metal, Metal Rods and Steel Wire

Dimensions: 88.9 x

101 x 99 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Rudolph

B. Schulhof Collection, Bequest of Hannelore B. Schulhof, 2012

© 2014 Calder Foundation, New York / SIAE, Rome, all Rights Reserved. CALDER ® is a Registered Trademark of Calder Foundation, NY.

© 2014 Calder Foundation, New York / SIAE, Rome, all Rights Reserved. CALDER ® is a Registered Trademark of Calder Foundation, NY.

ALEXANDER

CALDER

LE GRAND PASSAGE, 1974

Tempera and India Ink on Paper

Tempera and India Ink on Paper

Dimensions:

58 x 78 cm

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 139a

© 2014 Calder Foundation, New York / SIAE, Rome, All Rights Reserved.

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 139a

© 2014 Calder Foundation, New York / SIAE, Rome, All Rights Reserved.

CALDER

® is a Registered Trademark of Calder Foundation, NY.

MAX ERNST (1891 – 1976)

ATTIREMENT

OF THE BRIDE, 1940

Oil on

Canvas

Dimensions: 51 x 37 7/8 inches (129.6 x 96.3 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Movement: Surrealism

Attirement of the Bride is an example of Max Ernst’s veristic or

illusionistic Surrealism, in which a

traditional technique is applied to an incongruous or unsettling subject. The

theatrical, evocative scene has roots in late nineteenth-century Symbolist

painting, especially that of Gustave Moreau. It also echoes the settings and

motifs of sixteenth-century German art. The willowy, swollen-bellied figure

types recall those of Lucas Cranach the Elder in particular. The architectural

backdrop with its strong contrast of light and shadow and its inconsistent

perspective shows the additional influence of Giorgio de Chirico, whose

work had overwhelmed Ernst when he first saw it in 1919.

The pageantry and elegance of the image are contrasted

with its primitivizing aspects—the garish colors, the animal and monster

forms—and the blunt phallic Symbolism of the poised spearhead. The central

scene is contrasted as well with its counterpart in the

picture-within-a-picture at the upper left. In this detail the bride appears in

the same pose, striding through a landscape of overgrown classical ruins. Here

Ernst has used the technique of decalcomania invented in 1935 by Oscar

Domínguez, in which diluted paint is pressed onto a surface with an object that

distributes it unevenly, such as a pane of glass. A suggestive textured pattern

results.

The title of this work had occurred to Ernst at least

as early as 1936, when he italicized it in a text in his book Beyond

Painting. Ernst had long identified himself with the bird, and had invented an

alter ego, Loplop, Superior of the Birds, in 1929. Thus one may perhaps

interpret the bird-man at the left as a depiction of the artist; the bride may

in some sense represent the young English Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington.

Lucy Flint

MAX ERNST (1891 – 1976)

THE

ANTIPOPE, CA. 1941

Oil on Cardboard, Mounted on Board

Oil on Cardboard, Mounted on Board

Dimensions: 32.5 x 26.5 cm

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 79

© Max Ernst, by SIAE 2008

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 79

© Max Ernst, by SIAE 2008

MAX ERNST (1891 – 1976)

THE

ANTIPOPE, 1941 – 1942

Oil on

Canvas

Dimensions: 63 1/4 x 50 inches (160.8 x 127.1 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation,

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Movement: Surrealism

Max Ernst settled

in New York in 1941 after escaping from Europe with the help of Peggy

Guggenheim. The same year he executed a small oil on cardboard (now in

the Peggy Guggenheim Collection) that

became the basis for the large-scale The Antipope. When Guggenheim saw the

small version, she interpreted a dainty horse-human figure on the right as

Ernst, who was being fondled by a woman she identified as herself. She wrote

that Ernst conceded that a third figure, depicted in a three-quarter rear view,

was her daughter Pegeen; she did not attempt to identify another horse-headed

female to the left.¹ When Ernst undertook the large version from December to

March he changed the body of the “Peggy” figure into a greenish column and

transferred her amorous gesture to a new character, who wears a pink tunic and

is depicted in a relatively naturalistic way. The “Pegeen” figure in the center

appears to have two faces, one of a flayed horse that looks at the horse-woman

at the left. The other, with only its cheek and jaw visible, gazes in the

opposite direction, out over the grim lagoon, like a pensive subject conceived

by Caspar David Friedrich.

The great upheavals in Ernst’s personal life during

this period encourage such a biographical interpretation. Despite his marriage

to Guggenheim, he was deeply involved with Leonora Carrington at this time, and

spent hours riding horses with her. As birds were an obsession for Ernst, so

horses were for Carrington. Her identification with them is suggested

throughout her collection of stories La Dame ovale, published in 1939 with

seven illustrations by Ernst, two of which include metamorphosed horse

creatures. It seems plausible that the alienated horse-woman of The

Antipope, who twists furtively to watch the other horse-figure, represents a

vision of Guggenheim. Like the triumphal bride in Attirement of the Bride,

she wears an owl headgear. Her irreconcilable separation from her companion is

expressed graphically by the device of the diagonally positioned spear that

bisects the canvas. The features of the green totemic figure resemble those of

Carrington, whose relationship with Ernst was to end soon after the painting

was completed, when she moved to Mexico with her husband.

Lucy Flint

1. See P. Guggenheim, Out of This Century:

Confessions of an Art Addict, New York, 1979, pp. 261–62.

MAX ERNST (1891 – 1976)

THE ANTIPOPE, 1941 – 1942 (DETAIL)

MAX ERNST (1891 – 1976)

THE

FOREST, 1927 – 1928

Oil on

Canvas

Dimensions: 37 7/8 x 51 inches (96.3 x 129.5 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Movement: Surrealism

André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto of 1924

proclaimed “pure psychic automatism” as an artistic ideal, emphasizing

inspiration derived from the chance juxtaposition of forms and the haphazard

use of materials. Max Ernst came

under the influence of Breton’s ideas in 1924, and soon thereafter developed

his frottage or rubbing technique.¹ In making his first frottages, he dropped

pieces of paper at random on floor boards and rubbed them with pencil or chalk,

thus transferring the design of the wood grain to the paper. He next adapted

this technique to oil painting, scraping paint from prepared canvases laid over

materials such as wire mesh, chair caning, leaves, buttons, or twine. His

repertory of objects closely parallels that used by Man Ray in his experiments with Rayograms during the

same period. Using his grattage (scraping) technique, Ernst covered his

canvases completely with pattern and then interpreted the images that emerged,

thus allowing texture to suggest composition in a spontaneous fashion.

In The Forest the artist probably placed the canvas over a rough

surface (perhaps wood), scraped oil paint over the canvas, and then rubbed,

scraped, and overpainted the area of the trees.

The subject of a dense forest appears often in Ernst’s

work of the late twenties and early thirties. These canvases, of which The

Quiet Forest, 1927, is another example, generally contain a wall of trees, a

solar disk, and an apparition of a bird hovering amid the foliage. Ernst’s

attitude toward the forest as the sublime embodiment of both enchantment and

terror can be traced to his experiences in the German forest as a child.² His

essay “Les Mystères de la forêt,” published in Minotaure in 1934,

vividly conveys his fascination with the various kinds of forests. The Peggy

Guggenheim canvas resonates with those qualities he identified with the forests

of Oceania: “They are, it seems, savage and impenetrable, black and russet,

extravagant, secular, swarming, diametrical, negligent, ferocious, fervent, and

likeable, without yesterday or tomorrow. . . . Naked, they dress only in their

majesty and their mystery” (author’s translation).

Elizabeth C. Childs

1. For Ernst’s own account of frottage see Max Ernst,

“Favorite Poets and Painters of the Past,” in Ernst, Beyond Painting, and

other Writings by the Artist and His Friends (New York: Wittenbron,

Schultz, 1948), p. 7.

2. Max Ernst, “Some Data on the Youth of M. E. as told

by himself,” in Ernst, Beyond Painting, and other Writings by the Artist

and His Friends (New York: Wittenbron, Schultz, 1948), p. 27.

EDUARDO CHILLIDA

UNTITLED, 1974

Collage on Paper

Collage on Paper

Dimensions: 55.2 x 44.8 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Rudolph B. Schulhof Collection, bequest of Hannelore B.

Schulhof, 2012

© Eduardo Chillida, by SIAE 2012

© Eduardo Chillida, by SIAE 2012

EDUARDO CHILLIDA

UNTITLED, 1974

Collage on Paper

Collage on Paper

Dimensions: 55.2 x 44.8 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Rudolph B. Schulhof Collection, bequest of Hannelore B. Schulhof, 2012

© Eduardo Chillida, by SIAE 2012

© Eduardo Chillida, by SIAE 2012

EDUARDO CHILLIDA

UNTITLED, 1974

Collage on Paper

Collage on Paper

Dimensions: 55.2 x 44.8 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Rudolph B. Schulhof Collection, bequest of Hannelore B. Schulhof, 2012

© Eduardo Chillida, by SIAE 2012

© Eduardo Chillida, by SIAE 2012

EDUARDO

CHILLIDA

Untitled, 1974

Collage on paper, 55.2 x 44.8 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Collage on paper, 55.2 x 44.8 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Rudolph

B. Schulhof Collection, bequest of Hannelore B. Schulhof, 2012

© Eduardo Chillida, by SIAE 2012

© Eduardo Chillida, by SIAE 2012

MAN RAY ( 1890 – 1976)

SILHOUTTE,

1916

India

Ink, Charcoal, and Gouache on Wood Pulp Board

Dimensions: 20 15/16 x 25 1/4 inches (51.6 x 64.1 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Movement: Dada

In 1915 Man Ray abandoned what he called his

“Romantic-Expressionist-Cubist” style and adopted a mechanistic, graphic,

flattened idiom like that developed by Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp during

the same period. This drawing is preparatory to his most successful painting in

this style, The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows of

1916 (Collection The Museum of Modern Art, New York), the subject of which was

inspired by a vaudeville dancer whose movement he wished to suggest in a series

of varying poses.¹ Man Ray’s interest in frozen sequential movement may derive

from the experiments in photography he initiated about this time.

The particularized features of the figures in this

drawing are eliminated to produce two-dimensional patterned forms that are

silhouetted against black oval shadows. The dancer is accompanied not only by

her shadow but also by music, concisely indicated by the voluted head of an

instrument at the lower right of the support, the strings across the bottom,

and the music stand at left. The position of her feet on the strings, which may

double as a stave, may be meant to convey a specific sequence of notes, as if

the dancer were indeed accompanying herself musically. It seems likely that

this drawing represents the first stage in the conception of the painting. In

the canvas the three positions of the dancer are superimposed and appear at the

top of the composition, with the greater part of the field occupied by her

distorted, enlarged, and vividly colored cutout shadows.

Lucy Flint

1. Man Ray discusses the genesis of this work in his

autobiography, Self Portrait, Boston and Toronto, 1963, pp. 66–67,

71.

GIORGIO

DE CHIRICO

THE NOSTALGIA OF THE POET

THE NOSTALGIA OF THE POET

Oil and

Charcoal on Canvas

Dimensions: 89.7 x 40.7 cm

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 65

© Giorgio de Chirico, by SIAE 2008

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 65

© Giorgio de Chirico, by SIAE 2008

This work belongs to a series of paintings of 1914 on

the subject of the poet, the best known of which is the Portrait of

Guillaume Apollinaire. Recurrent motifs in the sequence are the plaster bust

with dark glasses, the mannequin, and the fish mold on an obelisk. These

objects, bearing no evident relationships to one another, are compressed here

into a narrow vertical format that creates a claustrophobic and enigmatic space.

As in The Red Tower, the use of inanimate forms

imitating or alluding to human beings has complex ramifications. The sculpture

at the lower left is a painted representation of a plaster cast from a stone,

marble, or metal bust by an imaginary, or at present unidentified, sculptor.

The character portrayed could be mythological, historical, symbolical, or

fictional. The fish is a charcoal drawing of a metal mold that could produce a

baked “cast” of a fish made with an actual fish. The fish has additional

connotations as a religious symbol, and the hooklike graphic sign toward which

its gaping mouth is directed has its own cryptic allusiveness. The mannequin is

a simplified cloth cast of a human figure—a mold on which clothing is shaped to

conform to the contours of a person. Each object, though treated as solid and

static, dissolves in multiple significations and paradoxes. Such amalgams of

elusive meaning in Giorgio de Chirico’s

strangely intense objects compelled the attention of the Surrealists.

Lucy Flint

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO (1888 – 1978)

THE RED TOWER, 1913

Oil on

Canvas

Dimensions:

28 15/16 x 39 5/8 inches (73.5 x 100.5 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Giorgio

de Chirico’s enigmatic works of 1911 to 1917 provided a crucial

inspiration for the Surrealist painters. The dreamlike atmosphere of his

compositions results from irrational perspective, the lack of a unified light

source, the elongation of shadows, and a hallucinatory focus on objects.

Italian piazzas bounded by arcades or classical façades are transformed into

ominously silent and vacant settings for invisible dramas. The absence of event

provokes a nostalgic or melancholy mood as if one senses the wake of a

momentous incident; if one feels the imminence of an act, a feeling of anxiety

ensues.

De Chirico remarked that “every object has two

appearances: one, the current one, which we nearly always see and which is seen

by people in general; the other, a spectral or metaphysical appearance beheld

only by some individuals in moments of clairvoyance and metaphysical

abstraction, as in the case of certain bodies concealed by substances

impenetrable by sunlight yet discernible, for instance, by x-ray or other

powerful artificial means.”¹ Traces of concealed human presences appear in the

fraught expanse of this work. One is the partly concealed equestrian monument

often identified as Carlo Marochetti’s 1861 statue of King Carlo Alberto in

Turin,² which also appears in the background of de Chirico’s The Departure

of the Poet of 1914. In addition, in the left foreground, overpainting

barely conceals two figures (or statues), one of which resembles a shrouded mythological

hero by the 19th-century Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin. The true protagonist,

however, is the crenellated tower; in its imposing centrality and rotundity it

conveys a virile energy that fills the pictorial space.

Lucy Flint

1. Quoted in William Rubin, “De Chirico and

Modernism,” in De Chirico, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art,

1982), p. 57.

2. James Thrall Soby, De Chirico, exh. cat. (New

York: Museum of Modern Art, 1955), pp. 49–50.

RENE MAGRITTE (1898 – 1967)

VOICE OF SPACE, 1931 (DETAIL)

RENE MAGRITTE (1898 – 1967)

VOICE

OF SPACE, 1931

Oil on

Canvas

Dimensions: 28 5/8 x 21 3/8 inches (72.7 x 54.2 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation,

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Movement: Surrealism

MARCEL DUCHAMPB (1887 – 1968)

NUDE

(STUDY), SAD YOUNG MAN ON A TRAIN, 1911 - 1912

Oil on

Cardboard, Mounted on Masonite

Dimensions: 39 3/8 x 28 3/4 inches (100 x 73 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation,

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/

Succession

Marcel Duchamp

Movement: Cubism

This painting, which Marcel Duchamp identified

as a self-portrait, was probably begun during December of 1911 in Neuilly,

while he was exploring ideas for the controversial Nude Descending a

Staircase, No. 2 of 1912. In Nude (Study), Sad Young Man

on a Train his transitory though acute interest in Cubism is manifested in the subdued palette, emphasis

on the flat surface of the picture plane, and in the subordination of

representational fidelity to the demands of the abstract composition.

Duchamp’s primary concern in this painting is the

depiction of two movements, that of the train in which we observe the young man

smoking and that of the lurching figure itself. The forward motion of the train

is suggested by the multiplication of the lines and volumes of the figure, a

semitransparent form through which we can see windows, themselves transparent

and presumably presenting a blurred, “moving” landscape. The independent

sideways motion of the figure is represented by a directionally contrary series

of repetitions. These two series of replications suggest the multiple images of

chronophotography, which Duchamp acknowledged as an influence, and the related

ideas of the Italian Futurists, of which he was at least aware by this time.

Here he uses the device not only to illustrate movement, but also to integrate

the young man with his murky surroundings, which with his swaying, drooping

pose contribute to the air of melancholy. Shortly after the execution of this

and similar works, Duchamp lost interest in Cubism and developed his eccentric

vocabulary of mechanomorphic elements that foreshadowed aspects of Dada.

Lucy Flint

MARCEL DUCHAMPB (1887 – 1968)

NUDE (STUDY), SAD YOUNG MAN ON A TRAIN, 1911 - 1912 (DETAIL)

ALEXANDER ARCHIPENKO

BOXING, 1935

Terra-Cotta

Terra-Cotta

Dimensions: 76.6 cm High

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 26

© Alexander Archipenko, by SIAE 2008

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 26

© Alexander Archipenko, by SIAE 2008

MAX

ERNST (1891 – 1976)

THE

KISS, 1927

Oil on

Canvas

Dimensions: 50 3/4 x 63 1/2 inches (129 x 161.2 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation,

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Movement: Surrealism

From humorously clinical depictions of erotic events

in the Dada period, such as Little Machine Constructed

by Minimax Dadamax in Person, Max Ernst moved on

to celebrations of uninhibited sexuality in his Surrealist works. His liaison

and marriage with the young Marie-Berthe Aurenche in 1927 may have inspired the

erotic subject matter of this painting and others of this year. The major

compositional lines of this work may have been determined by the configurations

of string that Ernst dropped on a preparatory surface, a procedure according

with Surrealist notions of the importance of chance effects. However, Ernst

used a coordinate grid system to transfer his string configurations to canvas,

thus subjecting these chance effects to conscious manipulation. Visually, the

technique produces undulating calligraphic rhythms, like those traced here

against the glowing earth and sky colors.

The centralized, pyramidal grouping and the embracing

gesture of the upper figure in The Kiss have lent themselves to

comparison with Renaissance compositions, specifically the Madonna and

Saint Anneby Leonardo da Vinci (Collection Musée National du Louvre, Paris).¹

The Leonardo work was the subject of a psychosexual interpretation by Sigmund

Freud, whose writings were important to Ernst and other Surrealists. The

adaptation of a religious subject would add an edge of blasphemy to the

exuberant lasciviousness of Ernst’s picture.

Lucy Flint

1. See the interpretation of this work by N. and E.

Calas in The Peggy Guggenheim Collection of

Modern Art, New York, 1966, pp. 112–13.

ANDRE MASSON

ARMOR, 1925

Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 80.6 x 54 cm

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 106

© André Masson, by SIAE 2008

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 106

© André Masson, by SIAE 2008

MARK

ROTHKO

UNTITLED

(RED), 1968

Acrylic on Paper, Mounted on Canvas

Acrylic on Paper, Mounted on Canvas

Dimensions: 83.8 x 65.4 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Rudolph

B. Schulhof Collection, bequest of Hannelore B. Schulhof, 2012

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / ARS, New York, by SIAE 2012

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / ARS, New York, by SIAE 2012

WOMAN WALKING, 1936

Bronze

Dimensions: 144.6 cm High

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 133

© Alberto Giacometti Estate / by SIAE in Italy, 2014

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 133

© Alberto Giacometti Estate / by SIAE in Italy, 2014

FRANZ

KLINE

UNTITLED, 1951

Ink on Paper

Ink on Paper

Credit

Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation,

Hannelore B. and

Rudolph B. Schulhof Collection, Bequest of Hannelore B.

Schulhof, 2012

© Franz Kline, by SIAE 2012

© Franz Kline, by SIAE 2012

STUART DAVIS

COLOR SKETCH FOR DRAKE UNIVERSITY MURAL

COLOR SKETCH FOR DRAKE UNIVERSITY MURAL

(STUDY FOR ALLEE)

Gouache on Paper

Dimensions: 24.7 x 90.8 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift, Earl Davis 97.4564

© Stuart Davis, by SIAE 2008

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift, Earl Davis 97.4564

© Stuart Davis, by SIAE 2008

RAOUL

HAUSMANN

UNTITLED, 1919

Watercolor on Paper

Watercolor on Paper

Dimensions: 38.8 x 27.5 cm

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 88

© Raoul Hausmann, by SIAE 2008

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 88

© Raoul Hausmann, by SIAE 2008

JEAN METZINGER (1883 – 1956)

AT THE

CYCLE-RACE TRACK, 1912

Oil and

Collage on Canvas

Dimensions: 51 3/8 x 38

1/4 inches (130.4 x 97.1 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Movement: Cubism

Jean Metzinger, a

sensitive and intelligent theoretician of Cubism, sought to

communicate the principles of this movement through his paintings as well as

his writings. Devices of Cubism and Futurism appear

in At the Cycle-Race Track, though they are superimposed on an image that

is essentially naturalistic. Cubist elements include printed-paper collage, the

incorporation of a granular surface, and the use of transparent planes to

define space. The choice of a subject in motion, the suggestion of velocity,

and the fusing of forms find parallels in Futurist painting. Though these

devices are handled with some awkwardness and the influence of Impressionism persists,

particularly in the use of dots of color to represent the crowd in the

background, this work represents Metzinger’s attempt to come to terms with a

new pictorial language.

Lucy Flint

JEAN METZINGER (1883 – 1956)

AT THE CYCLE-RACE TRACK, 1912 (DETAIL)

ALBERTO GIOCOMETTI (1901 – 1966)

STANDING

WOMAN (“LEONI”), 1947

Bronze

Dimensions: 60 1/4 inches (153 cm) high, including base

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP/FAAG, Paris

An early example of the mature style with which

Giacometti is usually identified, this figure is more elongated and

dematerialized than Woman Walking, although it retains that sculpture’s

frontality and immobility. A sense of ghostly fragility detaches the figure

from the world around it, despite the crusty materiality of the surfaces, as

animated and responsive to light as those of Rodin.

Giacometti exploited the contradictions of perception

in the haunting, incorporeal sculptures of this period. His matchstick-sized

figures of 1942 - 1946 demonstrate the effect of distance on size and comment

on the notion that the essence of an individual persists even as the body

appears to vanish, that is, to become nonexistent. Even his large-scale

standing women and striding men seem miniaturized and insubstantial. In 1947

the sculptor commented that “life size figures irritate me, after all, because

a person passing by on the street has no weight; in any case he’s much lighter

than the same person when he’s dead or has fainted. He keeps his balance with

his legs. You don’t feel your weight. I wanted—without having thought about

it—to reproduce this lightness, and that by making the body so thin.”¹

Giacometti sought to convey several notions simultaneously in his attenuated

plastic forms: one’s consciousness of the nonmaterial presence of another

person, the insubstantiality of the physical body housing that presence, and

the paradoxical nature of perception. The base from which the woman appears to

grow like a tree is tilted, emphasizing the verticality of the figure as well

as reiterating the contours of the merged feet.

Giacometti had the present cast made expressly for

Peggy Guggenheim.

Lucy Flint

ELLSWORTH KELLY

BLUE RED, 1964

Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 91.4 x 91.4 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Rudolph B. Schulhof Collection, bequest of Hannelore B.

Schulhof, 2012

© Ellsworth Kelly

© Ellsworth Kelly

ELLSWORTH KELLY

42 ND, 1958

Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 153.7 x 203.2 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Rudolph B. Schulhof Collection, Bequest of Hannelore B.

Schulhof, 2012

© Ellsworth Kelly

© Ellsworth Kelly

ELLSWORTH KELLY

GREEN

RED, 1964

Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 91.4 x 91.4 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Hannelore B. and

Rudolph

B. Schulhof Collection, bequest of Hannelore B. Schulhof, 2012

© Ellsworth Kelly

© Ellsworth Kelly

JEAN ARP

CROWN OF BUDS I, 1936

Limestone

Limestone

Dimensions: 49.1 x 37.5 cm

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 56

© Jean Arp, by SIAE 2008

Credit Line: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 56

© Jean Arp, by SIAE 2008

TANCREDI

TRANSPARENCIES

OF THE ELEMENTS, 1957

Wax Crayon and Gouache on Paper

Wax Crayon and Gouache on Paper

Dimensions:

68.7 x 99.2 cm

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 287

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 287

TANCREDI

UNTITLED, 1954

Gouache on paper,

Gouache on paper,

Dimensions: 69.9 x 99.8 cm

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 286

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553 PG 286

TANCREDI (1927 – 1964)

COMPOSITION,

1955

Oil and

Tempera on Canvas

Dimensions: 51 x 76 3/4 inches (129.5 x 195 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

©

Tancredi (Tancredi Parmeggiani)

Where Piet Mondrian used the

square as a unit with which to express a notion of space and infinity,

Tancredi, who saw his aims as parallel to those of Mondrian, seized on the

point as his module. He was intrigued by the point’s identity as the

determinant sign of location, the smallest indication of presence. Tancredi’s

ideas about infinite space and the use of the point within it were developed by

1951, when he settled in Venice. This work typifies the crowded, architectonic

compositions he painted before his visit to Paris in 1955.

Incomplete circles vibrant with undiluted pigment

radiate from pivotal points and swirl throughout the canvas. These appear

below, above, and amid rectangular slabs, the whole comprising a multilayered

scaffolding of light and color producing the illusion of extensive, textured

depth. Density of form and color increases toward the center of the

composition, which consequently appears to bulge forward from the corners,

illustrating Tancredi’s view of space as curved. The vitality of execution and

tactile richness reflect the influence of Jackson Pollock. The

choppy, animated repetition of color applied with a palette knife resembles

that of the French-Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle, with whom Tancredi

exhibited in 1954.

Lucy Flint

MANOLA VALDES

LAS MENINAS, 2000

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

MANOLA VALDES

LAS MENINAS, 2000

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

MANOLA VALDES

LAS MENINAS, 2000

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

MANOLA VALDES

LAS MENINAS, 2000

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

MANOLA VALDES

LAS MENINAS, 2000

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

Ten Etchings With Collage on Handmade Paper

Dimensions: case 67.5 x 52.4 x 5.4 cm, each 65 x 50 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift in honor of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

by Sandro Rumney and Art of This Century 2000.108

© Manolo Valdés, by SIAE 2008

MARINO MARINI

THE CLOVEN VISCOUNT, 1998 (CAST 2001)

Bronze

Bronze

Dimensions: 235 x 95 x 40 cm

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift of the Artist 2001.35

© Mimmo Paladino, by SIAE 2008

Credit Line: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Venice

Gift of the Artist 2001.35

© Mimmo Paladino, by SIAE 2008

JOAN MIRO (1893 – 1983)

PAINTING, 1925 (DETAIL)

JOAN MIRO (1893 – 1983)

PAINTING, 1925

Oil on

Canvas

Dimensions: 45 1/8 x 57 3/8 inches (114.5 x 145.7 cm)

Credit

Line: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Peggy

Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2018

Successió Miró/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Movement: Surrealism

During the mid- to late 1920s Joan Miró developed a

private system of imagery in which the motifs have symbolic meanings that vary

according to their context. By studying the constellations of these motifs, one

is encouraged to infer meanings appropriate to a particular painting.

In Painting two “personages” (the

designation Miró used for his abstract figures) and a flame have been

identified. The personage on the right can perhaps be read as a female because

of the curvaceous nature of the eight-shape, and by analogy with forms in other

paintings that are specifically identified by the artist as women. The black

dot with radiating lines can be interpreted as the figure’s eye receiving rays

of light, or as a bodily or verbal emission. The same motif appears

in Personage, also of 1925, in the collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New

York. Moons, stars, suns, or planets float at the upper left of several

canvases of the mid-1920s. In the present work the semicircular orange-red

image not only carries a cosmic implication, but also possibly doubles as the

head of the second personage, probably a male. This head is presented in a

combined full-face and profile view, in the manner of Pablo Picasso’s Cubist

portraits.

The flame, used repeatedly by Miró in this period, may

signify sexual excitation in this context. The erotic content that prevails in

much of his work in 1925 is particularly explicit in the Lovers series,

in which two figures approach each other or are united in sexual embrace. The

two figures in Painting are less clearly conjoined. The

submersion of legible subject matter and the ambiguity of the painting’s

meaning transfer the emphasis to the purely abstract qualities of the work.

Line and color articulate a language as complex and poetic as the hieroglyphic

signs that constitute the imagery. The generalized ground, rich in texture from

the uneven thinning of paint and the use of shadowy black, provides a warm and

earthy support for the expressive black lines, the areas of red and yellow, and

the staccato rhythm of dots.

Lucy Flint

MARINO MARINI

POMONA, 1945

Bronze

Bronze

Dimensions: 163,5 x 64,5 x 53,5 cm

Long Term Loan to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice