G

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE & JEAN TINGUELY: MYTHS & MACHINES

HAUSER & WIRTH SOMERSET

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE

& JEAN TINGUELY: MYTHS & MACHINES

HAUSER & WIRTH

SOMERSET

May 17, 2025

– February 1, 2026

‘We couldn’t sit down

together without creating something new, conjuring up dreams.’—Niki de Saint

Phalle, ‘A little of my story with you Jean’ (1996)

Niki de Saint Phalle

(1930 – 2002) and Jean Tinguely (1925 – 1991) are reunited in a major site-wide

takeover at Hauser & Wirth Somerset in collaboration with the Niki

Charitable Art Foundation. The first exhibition dedicated to both artists in

the UK will illustrate Saint Phalle and Tinguely’s visionary artistic output

and enduring creative collaboration over three decades. Two emblematic figures

of contemporary art, Saint Phalle and Tinguely defied conventional artmaking

and were fuelled with rebellion, in both life and art. The exhibition will

feature unseen works on paper and art décor by Saint Phalle, alongside her

Shooting Paintings and monumental open-air sculptures. Iconic kinetic machines

by Tinguely range from the 1950s to the final year of his life, in addition to

multifaceted collaborative works made by the duo throughout the 1980s.

The Bourgeois Gallery

introduces the artists’ distinct visual language, production methods and social

commentary that developed in parallel, and through collaboration, over the

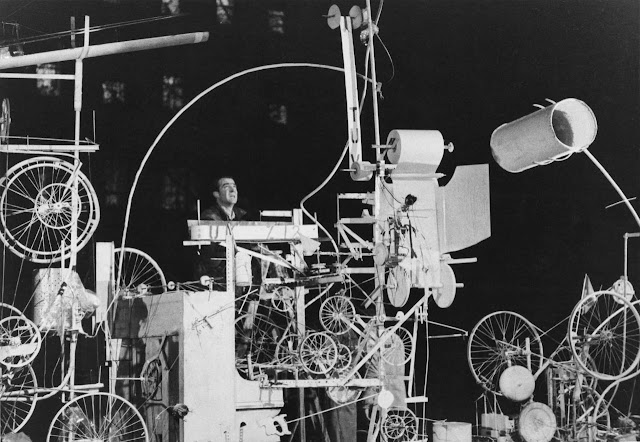

course of their careers. The Tinguely works within this space are exemplary of

his sculptural practice as research, exploring art based on movement, chance,

relative speed and sound. His ‘anti-machines’ feel more relevant now than ever

before, constructed from scrap metal and an assemblage of found materials,

designed to highlight the flaws of modern technology and society’s displacement

of humanity. Overlooking these works stands Saint Phalle’s ‘Big Lady (black)’

(1968/1995). By 1965, Saint Phalle began to introduce polyester to create more

voluptuous dancing figures that could be displayed in public parks and other

outdoor locations, as seen in ‘Les Trois Graces’ (1995 – 2003) that is

presented in the farmyard in Somerset.

The Rhoades Gallery

features Saint Phalle’s first functional sculptures, made for the film ‘Un Reve

plus long que la nuit’ (1976). The film was written, directed and acted by

Saint Phalle, alongside Tinguely and her daughter Laura Duke. Art and life were

interchangeable in Saint Phalle’s universe and the decorative elements for the

film, such as thrones, tables and mirrors, instigated a sustained interest in

making art to be lived with, which resulted in larger-scale immersive projects.

It was Saint Phalle’s passion for fantasy and mythology that contributed to

Tinguely’s monumental sculptural work, ‘Le Cyclop’ (1969 – 1994), in the forest

of Milly-la-Forêt, France, a project of boundless action between artists and a

dream of utopia. A mutual source of inspiration can be seen in ‘Le Grande Tête’

(1988), a union of Tinguely’s robust mechanical base with Saint Phalle’s

mysterious abstract face as a silent observer, a motif she began developing

from the 1970s, in response to multiple realities and dream states that can

exist simultaneously. Skating amongst the gold furniture is ‘Patineuse’ (c.

1967), from her most famous and recognizable series, the Nanas. Saint Phalle’s

army of brightly colored Nanas interrogate the various roles of women, often

liberated from tradition and radiating energy and vitality.

The Pigsty Gallery pays

homage to Saint Phalle’s Shooting Paintings, which began in 1961 against a

backdrop of political violence and unrest in France. Saint Phalle fired a rifle

at canvases or low reliefs resembling alters or effigies, often exploding bags

of hidden paint across the work’s surface. The process of creation was a

paradoxical destructive act, utilizing sensations of violence and demolition to

promote a sense of renewal and catharsis for the artist and the viewer. The

performative action was both inward-looking, demonstrating Saint Phalle’s

regaining of control and strength over a strict Catholic upbringing and abusive

father but, at the same time, responding to the period in which they were made,

and bursting with rage at institutional forces and masculinist values. Tinguely

was a primary supporter of these works and his own auto-exploding sculptures

and incendiarism in art shared this adventurous spirit and eagerness to

challenge artistic norms.

The Workshop Gallery

presents an intimate collection of drawings and works on paper by Saint Phalle,

many of which reflect on her relationship with Tinguely and the creative

stability and trust they provided for one another. The repetition of birds,

snakes, dragons and mythical creatures appear frequently in Saint Phalle’s

writings and sculptural work, drawing from the symbolic language of African,

pre Columbian and eastern cultures. Birds are often believed to be messengers

from one world to the next, representing complete freedom and immortal

reinvention. In addition to independent works by Tinguely, including ‘Radio

Sculpture’ (1961), ‘IBM’ (1960) and Rocker III (1963), stands a final

collaborative work, ‘Pallas Athéna (le chariot)’ (1989) that relates to the

seventh card in the Tarot which appears in Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden in

Garavicchio, Italy.

Saint Phalle’s extraordinary combination of architecture, the enchantment of nature, and the spiritual world is integral throughout her practice, most notably in her ambitious vision for the Tarot Garden. This is prominent across the open-air presentation in Somerset, including ‘The Prophet’ (1990), ‘Tête de mort I’ (1988), ‘Le Poète et sa Muse (1999) and ‘Les Trois Graces’ (1995-2003), alongside Tinguely’s ‘Fountain III’ (1963), a large motor-driven fountain on display in the Rhoades Gallery lobby that will be activated throughout the summer.

Hauser & Wirth Somerset’s Education Lab will take its starting point from Niki de Saint Phalle’s early experiences of personal trauma and embody her philosophy that creativity can serve as both a mental antidote and a therapeutic outlet. In partnership with the East Somerset Federation, consisting of Bruton Primary School, Ditcheat Primary School and Upton Noble C of E Primary School, the Education Lab will provide an interactive space realized by young people as an exploration of their emotions, experiences and stories.

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

Le Poète et

sa Muse, 1999

Polyurethane

Foam, Fiberglass Resin, Steel Armature, Stained and

Mirrored

Glass, Glass Pebbles on Metal Base Plate

Dimensions:

436.9 x 193 x 152.4 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE

Le Poète et sa Muse, 1999 (Detail)

JEAN TINGUELY

Metamatic No.

20, 1959/1960

Iron Tripod and Bars, Bicycle Wheels,

Rubber Belts, Two Cooking Pans

Dimensions:

224 x 161 x 110 cm

© Jean Tinguely, DACS 2025

JEAN TINGUELY

Metamatic No. 20, 1959/1960 (Detail)

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

Big Lady

(Black), 1968/1995

Painted

Polyester, Metal Base

EE; Ed. 1/1 +

EE

Dimensions:

247 x 157 x 80 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE

Big Lady (Black), 1968/1995 (Detail)

JEAN TINGUELY

Chandelier,

1989 – 1990

Metal,

Plastic Components, Antlers, Colored Light Bulbs

Dimensions:

254 x 172.7 x 152.4 cm

© Jean Tinguely, DACS 2025

JEAN TINGUELY

Chandelier, 1989 – 1990 (Detail)

JEAN TINGUELY

CH (dit

Pierre Joseph Proudhon), 1988

Iron, Wooden

Wheel, Bumper With CH Adhesive, Vine Root,

Rubber

Tensioner, V-Belt, Electric Motor V220

Dimensions:

198 x 80 x 70 cm

© Jean Tinguely, DACS 2025

JEAN TINGUELY

CH (dit Pierre Joseph Proudhon), 1988 (Detail)

JEAN TINGUELY

Fontaine

(CNAC No. 1), 1962

Welded

Sculpture (Water Machine), Iron Wheels and Support,

Car Parts,

Fan, Rubber Belts and Hoses, Electric Motor V220

Dimensions:

132.7 x 80.2 x 112.7 cm

© Jean Tinguely, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

Les Trois

Graces, 1995 – 2003

Polyester,

Mirror Mosaic

Dimensions: Silver

Sculpture: 289.6 x 124.5 x 94 cm /

Black Sculpture: 259.1 x 152.4 x 88.9 cm /

White Sculpture: 289.6 x 119.4 x 88.9 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

JEAN TINGUELY

Halleluja,

1984

Welded

Sculpture, Iron Chains and Metal

Wheels on

Tree Trunk, 220V Electric Motor

Dimensions:

110 x 120 x 120 cm

© Jean Tinguely, DACS 2025

JEAN TINGUELY

Halleluja, 1984 (Detail)

ABOUT NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE & JEAN TINGUELY

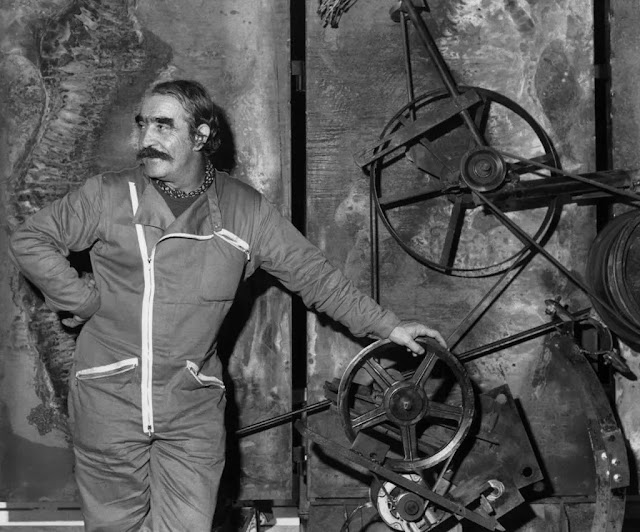

Niki de Saint Phalle

(1930 – 2002) and Jean Tinguely (1925 – 1991) were pioneering artists whose collaborative

works significantly influenced 20th Century art. Their partnership, both

personal and professional, began in the mid-1950s and spanned several decades.

Tinguely and Saint Phalle met and started working together in Paris, France,

eventually marrying in 1971. The pair forged an extraordinary personal and

artistic relationship that resulted in numerous groundbreaking projects that

combined their unique artistic visions.

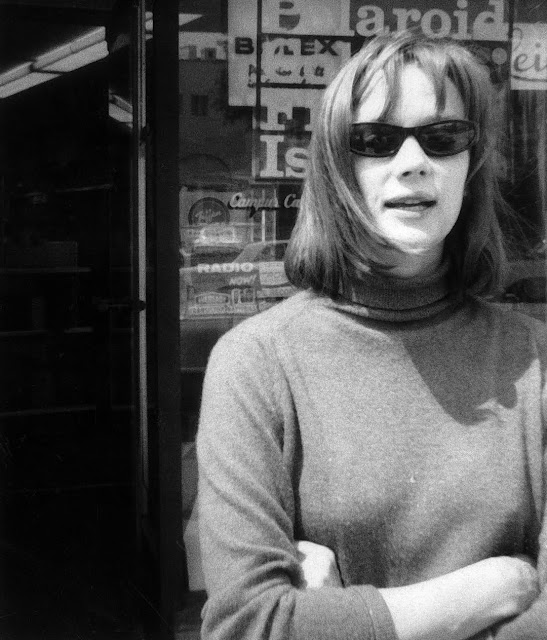

Niki de Saint Phalle was

born in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, but spent her childhood in the United

States. She was educated at a convent school in New York NY but spent her

summers in France. After a tumultuous childhood and a brief career in

modelling, she turned to art as a form of self expression and healing. Saint

Phalle was largely self-taught, drawing inspiration from diverse sources,

including Antoni Gaudí’s architectural works and indigenous art forms. Her

early works included the ‘Tirs’ series (1961 – 1964), in which she created

paintings by shooting at canvases embedded with bags of paint, a radical

approach that challenged traditional artistic methods. Saint Phalle gained

widespread recognition for her ‘Nanas’—large-scale, brightly colored sculptures

of female figures that celebrate femininity and fertility. Her most ambitious

projects was the ‘Tarot Garden’ (1979 – 2002) in Tuscany, Italy—a sculpture

park featuring monumental figures inspired by tarot cards. This endeavour

showcased her commitment to creating immersive environments that engaged

viewers on multiple levels.

Jean Tinguely was born in Fribourg, Switzerland, and grew up in Basel. He studied at the School of Arts and Crafts in Basel before moving to Paris, France, in the early 1950s. Tinguely became known for his kinetic sculptures, termed ‘Métamatics,’ which were mechanical constructions that incorporated movement and self-destruction, satirizing automation and the technological overproduction of material goods. Tinguely gained international attention with ‘Homage to New York,’ (1960) a self-destructing sculpture performed in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York NY. This piece epitomized his interest in the ephemeral nature of art and the fusion of creation and destruction. His works often featured salvaged materials and whimsical designs, engaging audiences in novel ways.

Notable collaborative projects between Saint Phalle and Tinguely include: ‘Hon – en katedral’ (1966), a monumental installation at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, featuring a giant reclining female figure that visitors could enter; the ‘Stravinsky Fountain’ (1983) near Centre Pompidou, in Paris, France, comprising 16 colourful sculptures inspired by Igor Stravinsky’s compositions; and ‘Le Cyclop’ (1969 – 1994), a monumental sculptural work in the forest of Milly-la-Forêt, France. Their collaborative efforts left an indelible mark on contemporary art, inviting audiences to engage with art in interactive and thought-provoking ways.

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE & JEAN TINGUELY

Nana Machine,

1976

Painted

Polyester, Iron Stand With Electric Motor by Jean Tinguely

Dimensions:

43.5 x 15 x 21 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE & JEAN TINGUELY

La Grande Tête, 1988

Iron, Wood, Electric Motor, Bungee, Lightbulbs,

Polyester Head by Niki de Saint Phalle

Dimensions: 225 x 225 x 140 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE & JEAN TINGUELY

Pallas Athéna (Le Chariot), 1989 (Detail)

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE & JEAN TINGUELY

Pallas Athéna (Le Chariot), 1989

Iron, Steel,

Electric Motor and a Statuette of Painted Polyester With Gold Leaf

Dimensions:

80 x 220 x 120 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

HOW DID THE ARTISTS MAKE THEIR WORK?

Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely’s collaborative making process was characterized by a dynamic interplay of materials, techniques and shared visions. Saint Phalle and Tinguely’s collaboration began with Saint Phalle’s request for Tinguely to construct an iron armature for her first sculpture in 1958. This initial collaboration evolved into a ‘four hands’ approach, where they alternated roles in the creative process. Saint Phalle would prepare, glue and paint, while Tinguely added elements like bent wires, resulting in unique assemblages that blended their individual styles.

JEAN TINGUELY

IBM, 1960

Iron Plate on

4 Screws, Computer Chip, Electric Motor

Dimensions:

26 x 26 x 12.5 cm

© Jean Tinguely, DACS 2025

JEAN TINGUELY

IBM, 1960 (Detail)

JEAN TINGUELY

Untitled from

Radio-Skulptur (Radio-Sculpture) Series, 1962

Iron Base,

Wheel With Tire, Radio, Wood Board, Electric Motor

Dimensions:

60 x 40 x 30 cm

© Jean Tinguely, DACS 2025

JEAN TINGUELY

Rocker III,

1963

Iron and

Electrical Components

Dimensions:

45 x 48 x 34 cm

© Jean Tinguely, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

Tête de Mort

I, 1988

Polyester,

Mirror, Palladium Leaf

Unique Series

of 6 (‘But’ all Different). Ed. 4/6

Dimensions:

114.3 x 127 x 86.4 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

Patineuse,

1967

Painted

Polyester, Metal Base

Dimensions:

200 x 160 x 115 cm

© 2025 Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All rights reserved

WHAT DOES THE EXHIBITION

LOOK LIKE?

In the exhibition, ‘Myths

& Machines,’ Saint Phalle’s and Tinguely’s works take over Hauser &

Wirth Somerset, marking the first time both artists work has been shown

together in the UK.

Beginning in the

Farmyard, ‘Le Poète et sa Muse’ (1999) and ‘Les Trois Graces’ (1995 – 2003) are

displayed as visitors’ first encounter with Saint Phalle’s iconic ‘Nana’

figures. These sculptures, depicting voluptuous, joyful women in dancing poses,

are symbols of femininity and empowerment. Each figure is covered in mirrored

glass, a mosaic technique often used by Saint Phalle to harness the physically

and personally reflective power of the mirror.

In the Bourgeois Gallery,

Tinguely’s iconic kinetic machines occupy the space, ranging from the 1950s to

the final years of his life. These assemblage creations such as ‘Deng Xiaoping’

(1989) and ‘Laika’ (1989) showcase his innovative fusion of movement and sound

through assemblages of metal, electric motors, and found objects such as

wheels, chains and animal skulls. Overlooking these works stands Saint Phalle’s

‘Big Lady (black)’ (1968/1995). By 1965, Saint Phalle began to introduce

polyester to create more voluptuous dancing figures that could be displayed in

public parks and other outdoor locations, as seen in ‘Les Trois Graces’ (1995 –

2003) that is presented in the farmyard in Somerset.

On view in the Rhoades

Gallery, ‘La Grande Tête’ (1988) is a key example of Tinguely’s and Saint

Phalle’s creative collaboration, originally an element from ‘La Fontaine de

Château-Chinon’ (1988), given to Château-Chinon by former French President,

François Mitterrand, which features Saint Phalle’s vibrant sculptures alongside

Tinguely’s kinetic elements.

Saint Phalle’s golden

furniture is showcased for the first time in the Rhoades Gallery, reflecting

her view that art and design are joined, not separate. This collection,

comprising thrones, tables, and mirrors crafted from metal, polyester, and gold

paint, was originally created as decorative elements for her recently restored

film ‘Un Rêve Plus Long Que La Nuit’ (1975). Saint Phalle both wrote and directed

this film, featuring performances by herself and Tinguely.Her furniture pieces,

Nanas series and ‘Patineuse’ (1966 – 1967) exude a fantastical and

fairytale-like quality, aligning with the film’s dreamlike narrative.

Examples of how Saint

Phalle pushed the boundaries of traditional artistic techniques are on view in

the Pigsty Gallery with her ‘Petit Autels’ (small altars) (1970 – 1972), made

in connection with her ‘Tirs’ (shooting paintings) which began in 1961. These

works involved embedding paint-filled containers within plaster-covered

structures, which Saint Phalle would then ceremoniously shoot with a rifle,

causing the paint to burst in a vivid, performative act. The act of shooting

these altars can be seen as a symbolic destruction of unjust and oppressive

constructs, such as the strictness of the Catholic Church Saint Phalle’s

parents raised her in, allowing for the creation of new, liberated forms. This

reflects Saint Phalle’s engagement with feminist themes, confronting societal

perceptions of femininity and empowerment.

Key examples of

Tinguely’s and Saint Phalle’s collaborations are on display in the Workshop

Gallery with ‘Nana Dasant (Nana Mobile)’ (1976), the only edition they made

together, and ‘Pallas Athéna (Le Chariot)’ (1989). This work relates to the

seventh card in the Tarot which appears in Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden in

Garavicchio, Italy. These works bring together Tinguely’s kinetic structures of

metal and motors and Saint Phalle’s sensual feminine sculptures, whilst still

bearing the signature of both artists. A collection of Saint Phalle’s 30 works

on paper, never exhibited before, are also shown, reflecting her exploration of

personal themes and societal commentary through form, color and composition.

Monumental open-air

sculpture, ‘The Prophet’ (1990) is on view in the Oudolf Field amongst the

garden’s landscaping. The piece is part of a series created by Saint Phalle

whilst in the Tarot Garden in Tuscany, Italy. Tinguely’s dynamic fountains are

exhibited, underscoring both artists’ efforts to blend art, movement and the

natural world into immersive experiences.

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

[Goddess

Creature], 1992

Watercolor,

Pencil on Photo Copy

Dimensions:

30.7 x 22.8 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

[Everything

is in Mouvement...], 1997

Felt Pen, Ink

Stamp, Sticker Collage, Watercolor, Pencil on Litho Paper

Dimensions:

27 x 23 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

[Design With

Face], Undated

Colored Ink

on Paper

Dimensions:

50.2 x 65.4 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

Lit (Élément

du Décor du Film ‘Un Rêve Plus Long Que La Nuit’), 1974

Polyester

Painted With Gold Paint, Metal Structure

Dimensions

Variable

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

JEAN TINGUELY

Le Cercle

Infernal de la Mort, 1990

Root Stock,

Iron, 11 Roebuck Skulls, Electric Motor

Dimensions:

200 x 170 x 120 cm

© Jean Tinguely, DACS 2025

JEAN TINGUELY

Le Cercle Infernal de la Mort, 1990 (Detail)

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

L’Autel des

Innocents, 1962

Various

Objects Embedded in Plaster, Plywood

Dimensions:

100 x 70 x 15 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

WHAT ARE THE MAJOR THEMES

WITHIN THE EXHIBITION?

REBELLION

Saint Phalle and Tinguely

viewed creation as an act of defiance against established norms. Their works

often convey aggressive undertones, challenging societal conventions through

bold and provocative expressions. Saint Phalle’s practice is testament to

artistic rebellion, intertwining aggressive subtexts with feminist ideals. Her

‘shooting paintings’ invited viewers to participate by shooting colour-filled

packets with rifles, transforming traditional art into an action-oriented

experience. This participatory approach not only garnered significant attention

but also aligned with the principles of action painting, emphasising the

physicality of creation. Central to her work are the ‘Nanas’, vibrant

sculptures of female figures that challenge conventional representations of

women, positioning them as ‘female warriors’ in the art world. These large

scale creations also assert the capability of female artists to produce

monumental works, reinforcing their presence in a domain historically dominated

by men. Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures often incorporated elements of disorder,

inviting viewers to engage with the unpredictable nature of his machines. Tinguely

not only questioned the role of the artist and the permanence of art but also

invited audiences to engage with the transient and often chaotic essence of

creation. Collaboratively, Saint Phalle and Tinguely pushed artistic

boundaries, embodying a shared commitment to using art as a vehicle for social

commentary and transformation.

HEALING

Niki de Saint Phalle’s

journey of healing through art is deeply rooted in her tumultuous early life

and personal challenges. Born into an aristocratic family that faced financial

ruin during the Great Depression, she endured a strict upbringing and a

traumatic childhood. Following a severe nervous breakdown that led to

hospitalization, Saint Phalle began creating collages using pebbles, leaves and

found materials. Encouraged by a friend who provided her with gouaches and

brushes, she developed a unique style that combined painting and assemblage.

Her early works, such as the shooting paintings, served as cathartic

expressions of her inner turmoil. In her later years, Saint Phalle continued to

explore themes of healing and self-discovery through monumental projects like

The Tarot Garden in Tuscany, Italy, envisioned as a place of reflection and and

restoration, described by Saint Phalle as ‘a promenade between nature and

culture.’ This process of artistic exploration became a vital means for her to

confront and process her emotions, dreams, and traumas, ultimately serving as a

therapeutic outlet that facilitated her personal healing and growth. Her life

and work continue to inspire discussions on the intersection of art and mental

health.

MOVEMENT & MECHANICS

Tinguely’s exploration of

movement and mechanics transformed static sculptures into dynamic, kinetic

experiences. Tinguely mechanized sculptural assemblages composed of found

objects, primarily scrap metal, introducing movement into his art. He referred

to these creations as ‘Métamatics,’ emphasising their self-referential nature

and challenging conventional notions of art and functionality. Tinguely’s works

often incorporated motors and moving parts, inviting viewers to engage with art

that was not merely observed but experienced through motion. This integration

of movement and mechanics not only expanded the possibilities of sculptural

expression but also served as a satirical commentary on the overproduction and

mechanisation prevalent in modern society. By infusing his sculptures with

movement, Tinguely invited viewers to reconsider their perceptions of art,

technology and the mechanized world around them, bringing freedom and life to

machines. As Tinguely remarked, ‘le movement c’est la vie (movement is life)’.

MYTH & FANTASY

Saint Phalle’s and Tinguely’s creative practices were imbued with fantasy and myth. Saint Phalle often immersed herself within the very sculptures she crafted, transforming these spaces into imaginative worlds that were creatively liberating. In her early drawings, Saint Phalle wove together vibrant, interlocking scenes populated by recurring motifs—fantastic creatures, fairytale landscapes and real-life imagery like cars, planes and skyscrapers—drawing inspiration from her environment and mythology. She wrote plays and films that built upon these motifs and fairytale landscapes, with a young girl as the heroine. Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures were not merely machines but whimsical creations that invited viewers into a playful, imaginative world. Tinguely’s work often incorporated sound, transforming everyday materials into fantastical entities. This imaginative world-building through sculptural reinvention invited viewers into a universe where fantasy and reality coalesced. This shared commitment to fantasy and imaginative expression was a cornerstone of both artist’s collaborative work to create immersive environments.

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE

L’Autel des Innocents, 1962 (Detail)

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

[Petit Autel]

(Small Altar), 1970 – 1972

Resin, Paint

Series of

Unique Works

Dimensions:

42 x 58 x 3 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE

[Petit Autel] (Small Altar), 1970 – 1972

Resin, Paint

Series of Unique Works

Dimensions: 42 x 58 x 3 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT PHALLE

[Petit Autel] (Small Altar), 1970 – 1972

Resin, Paint

Series of Unique Works

Dimensions: 42 x 58 x 3 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

Le Prophète

(The Prophet), 1990

Polyester

Resin, Resin Paint, Gold Leaf, Metal Base

Ed. 2/3

Dimensions:

270 x 70 x 70 cm

© Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025

ABOUT NIKI DE SAINT

PHALLE

1930 - 1949

Niki is born Catherine

Marie-Agnès Fal de Saint Phalle on October 29, 1930 in

France. Her father is French, her mother American. She is the second of five

children of a wealthy family who lose their business and fortune in the stock

market collapse.

She spends most of her

childhood and adolescence in New York City, though strong ties are maintained

with the family in France through frequent visits. As a teenager, in an early

display of her later artistic temperament, she paints the fig leaves of her

convent school’s classical sculptures red. She transfers to a new school

shortly thereafter.

As a

young woman, Niki’s first career is as a fashion model, with photographs

appearing in Vogue and Life. At 18, she elopes with childhood friend Harry

Mathews.

1950

-1959

In 1950, Niki begins making her first paintings while her husband

studies music at Harvard University. Laura, their first child, is born in

Boston in 1951.

In 1952, Niki moves to Paris to study theater and acting while

Harry studies music. They summer in the south of France, Spain, and Italy,

visiting museums and cathedrals.

In 1953, hospitalized for a nervous breakdown, Niki finds that

painting helps her to overcome this crisis and decides to give up acting and

become an artist.

After her recovery, Niki

and Harry briefly return to Paris, where she is encouraged by other artists to

continue painting in her unique self-taught style. They then move to Mallorca,

where son Philip is born in 1955.

In

Spain, Niki discovers the work of Antoni Gaudí and is deeply affected,

especially by Park Güell in Barcelona, which plants the idea to create her own

sculpture garden and inspires her to use diverse materials and found objects as

essential elements in her art.

Niki and

Harry return to Paris. Niki meets Jean Tinguely, who will become an artistic

collaborator. She is further inspired by the art of Paul Klee, Henri Matisse,

Pablo Picasso, and Henri Rousseau. Niki visits the Musée d’Art Moderne de la

Ville de Paris, where she also discovers the work of Jasper Johns, Willem de

Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Robert Rauschenberg.

1960 –

1964

In 1960, Niki and Harry separate and Harry moves to a new

apartment with the children. Niki sets up a studio and continues her artistic

experiments. She is included in an important group exhibition at the Musée

d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. By the end of the year Niki and Jean

Tinguely move in together, sharing the same studio and living in an artists’

colony.

In

the early 1960s Niki creates “shooting paintings” (Tirs),

complex assemblages with concealed paint containers that are shot by pistol,

rifle, or cannon fire. The impact of the projectile creates spontaneous effects

which finish the work. The shooting paintings evolve to include elements of

spectacle and performance. Niki becomes part of the Nouveau Réalisme group of

artists — the only woman in a group that includes Arman, Christo, Yves Klein,

Jean Tinguely, and Jacques de la Villeglé, among others.

Niki has

her first solo exhibition in Paris in 1961 and becomes

friends with American artists staying in Paris, including Robert Rauschenberg,

Jasper Johns, Larry Rivers, and his wife Clarice.

Marcel

Duchamp introduces Niki and Tinguely to Salvador Dali, with whom they go to

Spain for a celebration in his honor and create a life-size exploding bull out

of plaster, paper, and fireworks for the end of a traditional bullfight.

Niki is

included in The Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art in

New York.

In February 1962, Niki and Tinguely visit California and view

Simon Rodia’s Watts Tower in south Los Angeles. Niki and Tinguely travel around

California, Nevada, and Mexico, participating in exhibits and happenings.

Niki and Tinguely move to

an old country inn outside of Paris at the end of 1963.

Niki begins creating figurative reliefs — confrontational depictions of women,

some giving birth, as well as dragons, monsters, and brides.

1965 – 1969

Inspired by the pregnancy

of Larry Rivers’ wife Clarice in 1965, Niki makes her

first Nanas, archetypal female figures which are updated versions of

“Every(wo)man.” (The word “nana” is French for “dame” or “chick.”) For the

first exhibit of Nanas, Niki’s first artist book is published. This develops

into another of Niki’s prolific art forms: hand-lettered graphic works in the

form of invitations, posters, books, and other writings. In 1966, Niki collaborates on Hon (Swedish for

“she”) for the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. The outer form of Hon is a building-size giant reclining Nana with an

interior environment entered from between her legs. This piece garners

worldwide attention and intensifies her desire to build her own sculpture

garden.

Niki works with Tinguely

on Le Paradis Fantastique, a commission for the French

Pavilion at Expo ’67 in Montreal. Working on Le Paradis Fantastique, she is exposed to the toxic

fumes of polyester resin. This and other materials used in her work cause

severe damage to her lungs, resulting in recurrent health problems.

Niki designs Nana

inflatables, a multiple in plastic that are produced and distributed in the

United States.

1970 - 1974

Niki’s first permanent

architectural project is a private commission for a summer residence in the

south of France, completed in 1971. Niki begins to

develop other “fantastic” architectural projects that require intensive

planning and organization. Niki travels to India and Egypt, broadening the

repertoire of cultural experiences and visual associations used in her work.

Niki and Jean Tinguely

marry on July 13, 1971.

Niki receives a public

commission to create Golem, an architectural project

for children in Jerusalem’s Rabinovitch Park, which is completed the following

year.

In 1972, Niki receives a second private architectural

commission in Belgium and begins a productive association with art fabricator

Haligon for her large-scale sculptures and work in editions. Niki also makes

her first jewelry design for GEM Montebello Laboratory, Milan.

Niki creates three

large-scale Nanas for a permanent site near the town hall in Hannover, Germany

in 1974. The citizens nickname them Sophie, Charlotte, and

Caroline in honor of three historically distinguished women of Hannover.

Niki is hospitalized with

a serious lung ailment and recuperates in the Swiss mountains. While there, she

meets an old friend from her time in New York in the 1950s, Marella Caracciolo

Agnelli. Niki shares her dream of building a sculpture garden based on symbols

from the Tarot. Marella’s brothers, Carlo and Nicola Caracciolo, offer a parcel

of land in Garavicchio in Tuscany, Italy, as a site. The massive undertaking of

the garden will consume Niki’s thoughts and energies for nearly twenty years.

1975 - 1979

In 1975, her sculptural tableau Last Night I Had a Dream is

installed on the exterior of the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, for an arts

festival. She returns to Switzerland for a period of time and further develops

ideas for her Tarot Garden.

Niki makes first models

related to the figures that will be represented in the Tarot Garden,

and foundations are laid in 1978. In 1980, construction begins on the first architectural

sculpture, The High Priestess, representing female creativity and

strength. Niki will spend the major part of the next ten years on site

receiving assistance from many friends and supporters.

In 1982, she moves into The Empress, a

building designed in the shape of a sphinx that serves as her studio and home.

In 1979, Niki becomes interested in linear sculpture-drawings

in space and makes the Skinnies. This series of totem-like pieces often have

colored lights and elements suspended by string.

1980 - 1984

In 1980, the Ulm Museum organizes the first retrospective of

Niki’s graphic work. She receives a major retrospective at the Musée National

d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, which travels around Europe. She

also exhibits in Japan.

Niki creates the first of

her snake chairs, vases, and lamps that same year.

Niki creates a perfume,

with a sculptural vial, that bears her name for the Jaqueline Cochran Company

in 1982. The money from the perfume goes to finance the Tarot

Garden.

Niki and Tinguely

collaborate on a fountain next to the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. It is

an homage to Igor Stravinsky.

In 1983, Niki designs prints for a project to support the

Temporary Contemporary in Los Angeles. This work, in the form of a pictographic

letter, expresses her early awareness and concern for those afflicted by AIDS.

She continues to be involved in AIDS prevention and education efforts. The same

year the Stuart Foundation commissions a sculpture, Sun God, for the campus of the University of

California at San Diego. Niki suffers her first bouts of recurring and

debilitating attacks of rheumatoid arthritis.

1985 – 1989

From 1984 to 1987, Niki spends most of her time at the Tarot

Garden and completes several large structures, like the Magician, the High

Priestess, and the Empress. She begins a series of

flower vases in the shape of various animals.

In collaboration with Dr.

Silvio Barandun, Niki writes and illustrates the book AIDS: You Can’t Catch It Holding Hands. This

informative text, presented in a positive and compassionate format, is

published in seven languages. She has major retrospectives in Germany and

America.

At Jean Tinguely’s

request, Niki begins to decorate the face of his monumental sculpture Cyclop in

Milly-la-Forêt with “a sparkling cloak of mirror mosaic” in 1987.

It will be finished by 1991.

In 1988,

French President François Mitterrand commissions Jean Tinguely and Niki de

Saint Phalle to design a fountain for the town of Château Chinon and unveils it

in fornt of the townhall on March 10.

Niki revives a sculptural

theme from the mid-1970s by making L’Oiseau amoureux (Bird in

Love) a gigantic kite for a worldwide traveling kite exhibition.

1990 –

1994

In 1991, Niki makes a large-scale model for Le Temple Idéal, a place of worship for all religions.

This architectural sculpture was originally conceived in the early 1970s as a

response to the religious intolerance she observed while working in Jerusalem.

Niki received a commission from the city of Nîmes, France, to build Le Temple Idéal, but politics prevent the project from

being realized.

Jean Tinguely dies in

Bern, Switzerland in August 1991. In his honor, Niki makes

her first kinetic sculptures, the Meta-Tinguelys.

For

health reasons, at the end of 1993, Niki moves to La

Jolla, California, where she lives for next eight years. She establishes a

studio for working with mirrors, glass, and stones, which she is increasingly

using in her sculptures instead of paint.

1995 –

2002

Niki and Swiss architect

Mario Botta begin a major sculpture/architecture project, Noah’s Ark, in Jerusalem, which is inaugurated

in 2000.

Through 2000, Niki works on the Black Heroes series, an homage to

prominent African-Americans, including athletes and musicians such as Miles

Davis and Louis Armstrong.

Queen Califia’s Magical Circle is begun in

Escondido, California in 2000. She draws much of

its imagery from her interpretations of early California history, myth, and

legend, Native Americans and Meso-American culture, and the study of indigenous

plant and wildlife.

That year Niki is also

awarded the 12th Praemium Imperial Prize in Japan, considered to be the equivalent

to the Nobel Prize in the art world.

In 2001 Niki receives a commission to redesign and

ornament three rooms in the historic 17th century Grotto built in Hannover’s

Royal Herrenhausen Garden, originally decorated with shells, crystals, and

minerals, which were removed in the 18th century.

Niki de Saint Phalle dies

on May 21, 2002, at the age of 71 in La Jolla, California.

With work overseen by

Niki’s granddaughter, Bloum Cardenas, and her longtime assistants, her

remaining projects are completed. The Grotto opens in March 2003, with mosaic decorations of glass, mirrors, and

pebbles as well as a host of painted and sculpted figures. Queen Califia’s Magical Circle is dedicated and opens

to the public on October 26, 2003. This is her first

American garden and the last major project realized by the artist.

The Niki Charitable Art

Foundation, a non-profit organization, is established to promote and protect

Niki’s artistic legacy.

https://nikidesaintphalle.org/niki-de-saint-phalle/biography/#1930-1949

ABOUT JEAN TINGUELY

Jean Tinguely (Fribourg,

1925–Berne, 1991) was a pioneering artist of the 20th century who

revolutionized the concept of artwork and was a key figure of kinetic art,

which experimented with visual perception and movement during the 1960s and

1970s. At the heart of Tinguely’s work is the machine, seen not only as a

functional object but as a sculpture imbued with movement, sound, and its own

poetry. The artist transformed discarded objects and salvaged materials, such

as gears and scrap, into mechanical sculptures that are often ironic, noisy,

cacophonous, and have a life of their own thanks to complex motors and

mechanisms.

During his childhood,

Jean Tinguely lived in Basel, where, at the age of 16, he began an

apprenticeship working as a window decorator and during that time he followed

courses in drawing at the School of Applied Arts. Attracted by the radical

ideas of movements such as Dadaism, which emerged in Zurich in 1916, Tinguely

was drawn to art that rejected the conventional stanards of the time, pursuing

new forms of expression incorporating movement and perception. In 1953, he left

Basel for Paris, the vibrant center of the art scene, with his wife and fellow

artist Eva Aeppli (1925–2015). There, he worked on new compositions and

sculptures from wire and colored geometric shapes, inspired by the linear,

kinetic, and mechanical sculptures known as “mobiles” of the American artist

Alexander Calder (1898–1976). Another key influence was Marcel Duchamp

(1887–1968), a pioneer of conceptual art, who in the 1920s created works with

mechanisms and rotating circles that generated innovative optical effects.

At his first solo

exhibition at Galerie Arnaud in Paris in 1954, Tinguely presented a series of

wire sculptures called Méta-mécaniques, featuring small electric motors that

animated parts of the works. The title was coined by art critic Pontus Hultén

(1924–2006)—who would support him throughout his career and become a close

friend. The prefix méta was then used by Tinguely in many of his works to

underscore his intention to go beyond an idea and to emphasize the poetic

nature of his sculptures, as they autonomously generate art. With

Méta-mécaniques Tinguely sought to transcend the popular perception of

machines: while industrial devices typically produce material goods through

movement, these pieces, like much of his work, consisted of kinetic sculptures

that move without any productive purpose, thus defying the utilitarian function

and inviting contemplation on their intrinsic poetry. In December 1954, Italian

artist and designer Bruno Munari (1907–1998) invited Tinguely to exhibit a

number of works from this series at the Studio d’Architettura B24 in Milan,

marking their first presentation to the Italian public.

In addition to movement,

sound and, above all, noise become in time an important part of Tinguely’s

practice. The first notable example is Méta-mécanique sonore I (1955), a black

wall panel where small wire gears and hammers strike everyday objects like glasses,

bottles, and tins. The strikes occur at irregular intervals, producing a

chaotic and unpredictable sound effect. The Méta-Matics, made in 1959, were

among the first sculptures designed to actively engage viewers. These motorized

drawing machines are capable of making abstract works of art. One of the most

iconic pieces in this series is Méta-Matic No. 17, presented at the Paris

Biennial at the Musée d’Art Moderne in 1959, documented in renowned archival

photographs of the artist standing next to the machine, enveloped in puffs of

steam with the Eiffel Tower in the background.

In 1960, Tinguely

traveled to New York City for the first time, where he was captivated by the

fervor and chaos of the city. On March 17, in the Sculpture Garden of the

Museum of Modern Art, he presented the notorious sculpture-performance Homage

to New York (1960), a 7-meter long and 8-meter-high installation consisting of

approximately 80 bicycles, as well as tricycles, wheels, a bathtub, bells,

horns, bottles, cans, and several motors. As intended by the artist, the

machine destroyed itself in just 27 minutes. From then onwards, the

spectacular, transformative nature of his work—seen by Tinguely as a way of

bringing art closer to life—became increasingly evident in his production. For

instance, the exhibition at the Galerie des Quatre Saisons that opened in Paris

in May 1960, upon his return from New York City, was preceded by “Le

transport,” a parade of his latest mechanical “creatures,” including Gismo and

L’appareil à faire des sculptures (both from 1960 and featured in Pirelli

HangarBicocca). Led by the artist and a few friends, these works were rolled

from his studio on Impasse Ronsin to the gallery in an unusual procession that

was promptly halted by the police.

From the 1960s onwards,

Tinguely held several solo exhibitions in institutions and museums,

collaborating frequently with other artists on art projects, public works, and

exhibitions. One of the most famous was “Dylaby (Dynamic Labyrinth),” held at

the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1962, which consisted of an exhibition

conceived as a labyrinth strewn with physical obstacles, creating a challenging

and immersive experience for visitors. The project was designed by Tinguely

together with other artists, including Niki de Saint Phalle (1930– 2002)—who

had by then become his life partner—Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), and Daniel

Spoerri. During this period, Tinguely began using found objects in his

sculptures and installations, including organic elements such as fur and

industrial scrap. These works, marked by unpredictable sounds and movements,

surprised and amused viewers. This phase coincided with Tinguely’s involvement

in the Nouveau Réalisme movement, founded by art critic Pierre Restany

(1930–2003) in 1960. Artists in this movement approached reality in new ways,

using everyday objects and, above all, the waste and remnants of consumer

society into their works. Indeed, it was from an assemblage of scrap metal that

Tinguely made his series of kinetic fountains installed in public spaces,

including the famous Fasnachtsbrunnen created for the city of Basel in 1977.

In the 1980s, Tinguely’s

art reached a peak of noise, grandeur, and color. In 1987, Palazzo Grassi in

Venice hosted his most extensive retrospective to date, featuring over 90

installations, including his monumental mechanical, noise, and mobile

creations. Among these was Grosse Méta-Maxi-Maxi-Utopia (1987), 17 meters long

and 8 meters high, designed to be walkable by the public. In 1988, the artist

acquired La Verrerie, an abandoned glass factory covering an area of over 3,000

square meters near Fribourg and Lausanne, which he transformed into the

“Torpedo Institut.” Conceived as an “anti-museum,” it was intended as a space

to embrace constant evolution, encouraging cross-pollination between art and

everyday life. On the occasion of his funeral on September 4, 1991, more than

10,000 people took part in a memorial parade in Fribourg in honor of Tinguely.

According to the artist’s last wishes, the procession was led by Klamauk

(1979), a sound sculpture mounted on an old tractor with various percussion

instruments. Amidst puffs of smoke and exploding firecrackers, it made its way

through the crowd gathered to pay their last respects to the artist.

SELECTED

EXHIBITION

Many international institutions have hosted solo exhibitions by Jean Tinguely, including Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf (2016); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2016, 1984, 1973); Centro Cultural Borges, Buenos Aires (2012); Henie Onstad Art Centre, Oslo (2009); Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Valencia (2008); Kunst Haus Wien (2008, 1991); Kunsthal Rotterdam (2007); Stadtgalerie Klagenfurt, Klagenfurt am Wörthersee, Austria (2003); Städtische Kunsthalle, Mannheim, Germany (2002); Musée Picasso, Antibes (1999); Museum für Kunst und Geschichte, Freiburg (1991); Central House of the Artist, Moscow (1990); Centre Pompidou, Paris (1988); Palazzo Grassi, Venice (1987); Louisiana Museum, Humlebaek, Denmark (1986, 1973, 1961); Museum of Modern art of Shiga, Japan (1984); Musée Rath, Geneva (1983); Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, Tate Gallery, London, Kunsthaus, Zurich (1982); Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, Germany (1978); Kunstmuseum Basel (1976, 1972); Museum of Modern Art, New York City (1975, 1961); Moderna Museet, Stockholm (1972, 1966); Centre National d’Art Contemporain, Paris (1971); Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (1968); Dayton Art Institute, Ohio (1966); The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (1965); Kunsthalle, Baden-Baden, Germany (1964). The artist has taken part in numerous group shows, such as Biennale de la sculpture, Yonne, France (1991); Biennale Monumenta, Middelheim, Antwerp (1987); Biennale de Paris (1982); documenta, Kassel (1968); Expo - International and Universal Exposition, Montréal (1967); Expo – Exposition Nationale Suisse, Lausanne (1964); Venice Biennale (1964); Salon de Mai, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (1966, 1964). An entire museum has been dedicated to Jean Tinguely, the Museum Tinguely in Basel, a unique and interactive space, which opened in 1996 and houses the world’s largest collection of his works, many of which were donated by Niki de Saint Phalle.

You may click below link

to see ‘’ JEAN TINGUELY AT PIRELLI HANGARBICOCCA

MILAN’’ exhibition news from My Magical Attic.

https://mymagicalattic.blogspot.com/2025/01/jean-tinguely-at-pirelli-hangarbicocca.html

.png)