AMERICAN PAINTER CY TWOMBLY

AMERICAN PAINTER CY TWOMBLY

In 1962 Cy Twombly

(born 1928 in Lexington, Virginia) painted a work that illustrates many of the

abiding engagements of his practice. Untitled is divided into two zones by a

horizontal line about two thirds of the way up. Across the bottom edge of the canvas,

Twombly has scribbled a textual fragment gleaned from the poet Sappho: “But

their heart turned cold + they dropped their wings.” The phrase, suggesting a

hovering between higher and lower realms, conjures up a distant classical

realm, even as the grappling, awkward hand renders the words materially present.

In the upper third

of the canvas, the artist provides a code for viewing: a white circle swirled

with pink is labelled “blood”; an aggressive red “x” reads “flesh”; a glutinous

dollop of brown paint, “earth” or possibly “youth”; a delicate disc of wispy

white paint, “clouds”; and a shiny coin-shaped form in graphite pencil,

“mirror”. Beneath this code, Twombly has rendered, within a drawn frame, an

array of possibilities for mark-making per se, as though to set them apart from

the more direct references of words.

The elements of the

code come from three distinct experiential fields: the elemental (earth and

clouds), the somatic (flesh and blood) and the subjective (mirror). And they

can be mapped on to three corresponding traditional genres of oil painting,

respectively: landscape, figure and self-portraiture. In Untitled we see

Twombly’s invocation of myth and poetry, his wavering between high and low and

his sustained dwelling on the threshold where writing becomes drawing or

painting. Perhaps most importantly, we see in this painting how marks and words

– in collaboration and counter-distinction – construct meaning differently. As

John Berger has written, Twombly “visualises with living colours the silent

space that exists between and around words”.

Although his work

resonates strongly with generations of younger artists, ranging from Brice

Marden to Richard Prince to Tacita Dean, it has a general propensity to

polarise its audience between perplexity and unbridled admiration. (Remember

the incident in summer 2007 of a woman planting a lipstick kiss on a Twombly

canvas on show in Lyon?) Additionally, the critical and historical reception

has seemed to describe two Twomblys – one about form, the other about content.

Some writers have

concentrated on the materiality of the artist’s mark as aggressive, often

illegible graffiti; others have followed the classical allusions to ferret out

the references. Two elements might serve as metaphors for the predominant

interpretations: the floating disc of white paint labelled “clouds” standing

for the poetic and mythological aspects, and the scatological heap of brown

paint designating “earth”. However, Twombly’s painterly palimpsests trace the

progressions through which form and content, text and image are inextricably

linked.

EARTH &

YOUTH

Cy Twombly

arrived in Manhattan in 1950 while the New York School painting of Pollock and

de Kooning was in full swing. Upon Robert Rauschenberg’s encouragement, Twombly

joined him for the 1951–1952 sessions at Black Mountain College near Asheville,

North Carolina – a liberal refuge, a site of free

experimentation

and exchange in a nation growing increasingly conservative during the Cold War.

Among the influential teachers present at this time were Charles Olson, Franz

Kline, Robert Motherwell and John Cage. Building on the freedom afforded by the

previous generation, the younger artists emphasised libidinal energy integrated

through experience.

They focused

attention on calligraphic gesture and word/image relationships resulting in

work that was more syncretic, less spontaneously automatist. Works such as

Twombly’s Min-Oe (1951) bear evidence of the poet Olson’s interests in the

roots of writing in ancient cultures and condensed glyphic forms.

For eight

months spanning 1952–1953 Twombly and Rauschenberg travelled through Europe and

north Africa, joined for a while by the writer Paul Bowles. Upon returning to

New York, Rauschenberg set up the Fulton Street studio that Twombly sometimes

shared. Eleanor Ward invited the two artists to exhibit at her Stable Gallery.

A series of

Twombly’s works on light grounds dating to 1955 were given curious titles from

a list collaboratively compiled by Twombly, Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns –

Criticism, The Geeks, Academy. Here, pencil and crayon lines are inscribed into

viscous light greyish brown paint. Among the anxious, discontinuous thickets,

basic signs and letters begin to appear.

In 1957,

having built a bridge of connections with Italian artists showing frequently at

the Stable Gallery, Twombly left again for Italy, where he would remain for the

most part, though making frequent trips, including many to the States. He

established a studio in Rome overlooking the Colosseum and wrote a short

statement for the Italian art journal L’Esperienza moderna, which was to remain

the sole published reflection on his own work until 2000, when he was

interviewed by David Sylvester. In the statement, Twombly describes his

process: “Each line is now the actual experience with its own innate history.

It does not illustrate – it is the sensation of its own realisation.”

Works from

this era bear out the description. In Arcadia, for example, it is as though he

taps into the nervous system, harnessing an alert state of tension, letting it

come through in abrupt bursts at a level where it is generally inhibited by the

body’s higher functions, registering its insistent throb in stuttering,

jittery, whiplash lines. His move to Italy also afforded him ready access to

the Mediterranean repository of classical ruin and reference. In works such as

Olympia, words and names – “Roma”, “Amor” – emerge out of a network of marks.

In 1959

Twombly executed some of the most spare works of his career, among them the 24

drawings that comprise Poems to the Sea, done on the coast of Italy at

Sperlonga. What order of poems, punctuated with numerals and question marks,

are these? The sea is reduced to horizon line and word, scribblings and veils

of paint against the stark white of paper. A persistent compulsion is invoked

in the viewer, the desire to read what is there, but not fully manifest in the

artist’s scrawled script. Two words in these drawings emerge into legibility,

“time” and “Sappho”, as if washed up on the beach alongside sudden, subtle

gem-flashes of colour – blue, orange-yellow, pink – gleaming all the more

because of their discretion.

In these

pages, meaning is endlessly frustrated and pursued. It settles only in the

distance, figured perhaps by the horizon lines that move across the top of each

of the drawings – in fact, simply grey or blue lines made with a straight edge,

but suggesting seascapes at the vanishing point. The flat planes of sea and

page have been collapsed. Writing comes in waves, rolling funnels of cursive

script, crossed out, erased, enfoamed in satiny greyish-white paint. The signs

are given as nascent forms, as gestural indications of “the hand’s becoming”,

as Roland Barthes so aptly phrased it.

FLESH & BLOOD

In the autumn of

1960 Twombly had his first solo show at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York.

Moving into the 1960s, thick and florid colour comes into his work, along with

multiple classical references. During the prolific summer of 1961, he reached a

fever pitch, a colouristic crescendo in the Ferragosto paintings. A thickly

encrusted palette of brown, pink and red takes on a viscerality paired in the

work with a body parcelled into pictograms: pendulous breasts, erupting

penises, scatological posteriors. From 1961 to 1963 mythological motifs appear

with increasing insistence: Leda and the Swan, Venus, Apollo, Achilles. This

line of investigation culminated in 1963 with a series of works called Nine

Discourses on Commodus, an obscure portrait of the megalomaniacal Roman emperor

conceived while Twombly was reading the French novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet and

looking at the paintings of Francis Bacon. These works were shown at Castelli

in 1964, to a New York art world which had by then turned to Pop and Minimalism.

Following this

exhibition, Twombly’s American enthusiasm ebbed for a number of years. The

situation was quite different in Europe, where his work remained a critical

success. Nevertheless, the Commodus exhibition represents a crucial moment of

rupture in the artist’s career, for, as he commented, it made him “the happiest

painter around for a couple of years: no one gave a damn what I did”.

Approaching the end of the 1960s, Twombly employed a monochrome grey ground.

In 1966 white

writing in looped repetitive script appears on blackboard-like surfaces. The

works, which continue into the early 1970s, resemble rudimentary handwriting

tests, registering the muscular rhythms of the arm relaxing and tensing, and

seem to eschew outside reference; but Leonardo da Vinci’s Deluge drawings and

the Italian Futurists’ spatio-temporal explorations echo through them.

CLOUDS

Beginning in 1975,

Twombly had been working towards increasingly integrated combinations of text

and image; of lines – both written and drawn – and colour. The repeated returns

to the rich resources of classical mythology have remained the complications of

his work. He employs myth as yet another form in conjunction with painting,

drawing and writing. He sometimes suggests myth’s first seminal stirring,

letting only hermetic fragments come to the surface as names from the past:

Hero and Leander, Orpheus, Bacchus. At other times he offers a full-blown line

or verse burdened with all of its cultural and poetic associations like a tree

overripe with fruit. Roberto Calasso has written of the Greek myths: “All the

powers of the cult of gods have migrated into a single, immobile and solitary

act: that of reading.” Twombly’s caveat, however, would be that the gods’

powers lie not in a single act, but in the mobilisation of the space between

reading and seeing.

We see this in works

such as Venus and Apollo (both 1975). In Venus the name of the goddess is

written out in a palimpsest of red lines with a blossom drawn in crimson oil

stick beneath. She is attended by a pencil-drawn list of her various names

(Nadyomene, Aphrodite, Nymphaea…) and of her associations (myrtle, poppy,

apple, sparrow…). “Venus” is written out so as to emphasise the openness of the

“V”, “N” and “U”. In the pendant drawing, “Apollo” is delineated in dark blue

with a triangle, the Greek delta, serving as the first initial and doubling as

a directional pointer upward. Like the delta, the two letters “o” of the name

are closed forms, as against the five open letters of Venus. Apollo, too, is

accompanied by a list of his many names and attributes (laurel, palm, tree,

hawk, grasshopper…). In these drawings, no direct definition is provided (no

goddess of love or god of measure), but rather a network of allusions given

both word and form.

The Whitney Museum

of American Art mounted a retrospective exhibition in 1979 intended to rectify

Twombly’s relative absence on the American scene. Roland Barthes, upon the

artist’s suggestion, wrote the catalogue essay, “The Wisdom of Art”. In his

tendency to promote a proliferating, reference-laden and intricate web of text,

Barthes met his match with Twombly, whose work he described as “inimitable”:

“It is in a smear that we find the truth of redness; it is in a wobbly line

that we find the truth of a pencil.” The exhibition made only a small splash,

critiqued by some for being “too European”. Twombly was still in Rome and very

much outside the dominant narratives of contemporary American art of the time.

The Green series,

Untitled [A Painting in Nine Parts], is a sustained investigation of colour set

in relation to Rainer Maria Rilke’s poetry and Monet’s art. Clearly gesturing

toward landscape painting, this work seems to be the most mimetic of Twombly’s

oeuvre, yet it is also the most rawly material – suggesting the two primary

paths taken in the decades to follow.

The green Untitled

was executed in the spring of 1988 in Rome, the wood panels covered in

quick-drying acrylic (for speed was of the essence in these shots of propulsive

vernal energy). Part 1 functions like a title page: two lines from Rilke’s

Moving Forward pencilled in Twombly’s cursive hand (“… and in the ponds broken

off from the sky, my feeling sinks as if standing on fishes”) flutter down the

plane of white. “Fishes”, written in shimmery silver-grey oil stick near the

bottom of the panel, spans from edge to edge, even moving on to the white

frame. Words read as though seen through rippling water. Rhythmic spurts of

graphic attention create a visual analogue to the assonance of the words. The

hesitations around the letter “s” swish like fish. In the other panels, words

seem to be losing the battle with a superabundance of verdure. Groping finger

streaks of deep emerald green have the look of sea grasses shimmying in shallow

water.

Monet’s Water Lilies

enter the frame of reference. The effect of spatial disorientation and the

congested surfaces of these pond-panels suggest something of metaphorical

drowning. The myth of Narcissus, in which identity is swallowed up by mirror

reflection, lurks somewhere beneath these works.

MIRROR

In 1994 the Cy Twombly Gallery in Houston, Texas – designed by

Renzo Piano from Twombly’s original conception – opened as a joint project

between the Dia and Menil Foundations to house an extensive permanent

collection of the painter’s work. That same year, the Museum of Modern Art in

New York mounted a Twombly retrospective curated by Kirk Varnedoe. It met with

success and marked a dramatic shift in his American reception. This was due

largely to the curator’s mission of reinstating the artist’s grand themes into

an individual poetics. Varnedoe essentially reads Twombly’s work as

sublimation: “[Twombly] used the new art he created precisely to reforge, in a

wholly different poetics of light and sexuality that was specific to his

experience, the link between the heritage of the human past and the life of a

personal psyche.”

Concurrent with the MoMA retrospective, Twombly exhibited his

Untitled (Say Goodbye Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor) (1994) at the

Gagosian Gallery in New York.The monumental piece measuring four by sixteen

metres, a meditation on ageing and homecoming, offers an extraordinary array of

types of mark, range of chromatic dynamics from the faintest stain of pale grey

to outbursts of overripe wines and vibrant yellow-oranges, and a large body of

associative references (to name only a few: Robert Burton’s Anatomy of

Melancholy, Keats, Catullus, Archilochus, Turner).

The painting is intended to be read from right to left, like a

Chinese scroll, marking the direction of Twombly’s return over the Atlantic as

it does the movement of soul boats crossing the Nile, the primary pictorial

theme. The varied marks also weave a complex web of connections to myth,

poetry, history, memory, conventions of painting and earlier moments in

Twombly’s career.

Untitled was undertaken over a period of nearly 22 years, from 1972

to 1994. Just before it was about to be installed in the Cy Twombly Gallery in

Houston, Twombly called Paul Winkler, then director of the Menil Collection; he

had found a disused factory with enough wall space to hang the work in

Lexington. The painting was rolled up and two Menil couriers were dispatched in

an ice storm to deliver the work so that Twombly could rework it, yet again,

before it was permanently hung. The anxiety around finishing this painting

belies the artist’s thought expressed to Winkler, that it would be his last. It

was not. He had been extremely prolific since 1994.

The Bacchus series from 2005, for example, with its rush of roseate

pigment and whorls of gestural energy, shows an extra-ordinary exuberance.

© Claire Daigle

On the 5th July 2011, Cy Twombly died in hospital in Rome at the

age of 83.

http://www.cytwombly.info/index.html

IDES OF MARCH 1962

Oil and Pencil on

Canvas

Dimensions: 173 X 199 CM

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 173 X 199 CM

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED -

2007

Gaeta

Acrylic, Wax Crayon, Lead Pencil on WoodenPpanel

Dimensions: 252 x 552 cm

Gaeta

Acrylic, Wax Crayon, Lead Pencil on WoodenPpanel

Dimensions: 252 x 552 cm

All

artworks by Cy Twombly © Cy Twombly Foundation

UNTITLED II, 1967

Published

by Universal Limited Art Editions

(American,

Founded 1955)

Printed

by Donn Steward

FIFTY DAYS AT ILIAM:

THE FIRE THAT CONSUMES ALL BEFORE IT - 1978

Oil, Oil Crayon, and

Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 300 X 192 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 300 X 192 cm

© CY Twombly

LIBATION OF PRIAPUS, 1982

Oil, Crayon and coloured Pencil on Paper

Dimensions: 167 X 118.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 167 X 118.8 cm

© CY Twombly

SCENT OF MADNESS,

1986

Watercolour on Paper

Over a Print

By Betty di Robilant

Dimensions: 50 X 36.2 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 50 X 36.2 cm

© CY Twombly

SCHOOL OF ATHENS, 1964 - ROME

Oil Paint, Wax Crayon, And Lead Pencil on Canvas

Dimensions: 205 X 219 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 205 X 219 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED - 2005

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 325.1 x 494 cm.

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 325.1 x 494 cm.

All artworks by Cy Twombly © Cy Twombly Foundation

FERRAGOSTO IV, 1961 ROME

Oil Paint, Wax Crayon, and Lead Pencil on Canvas

Oil Paint, Wax Crayon, and Lead Pencil on Canvas

Dimensions: 165.5 X 204 cm

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

III NOTES FROM SALALAH, NOTE II, 2005 - 2007

Acrylic on Wood Panel

Dimensions: 243.8 X 365.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 243.8 X 365.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Cy Twombly + Relics, Robert Rauschenberg, Rome 1952

THE ROSE (IV), 2008

Acrylic on

Plywood

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

THE ROSE (II), 2008

Acrylic on Plywood

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

THE ROSE (III), 2008

Acrylic on Plywood

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

THE ROSE (I), 2008

Acrylic on

Plywood

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

THE ROSE (V), 2008

Acrylic on Plywood

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED (ROSES) GAETA - 2008

Acrylic on Plywood

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED (ROSES) GAETA - 2008

Acrylic on Plywood

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X 740 cm

© CY Twombly

Cy Twombly in Fulton Street Studio. Robert Rauschenberg, New

York 1954

QUATTRO STAGIONI,

PART I: PRIMAVERA, 1993-94

Synthetic Polymer

Paint, Oil, House Paint,

Pencil and Crayon on

Canvas

Dimensions: 312.5 X 190 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 312.5 X 190 cm

© CY Twombly

QUATTRO STAGIONI:

AUTUNNO, 1993-5

Acrylic, Oil,

Crayon, and Pencil on Canvas Support:

Dimensions: 3136 X 2150 X 35 mm

Frame: 3230 X 2254 X 67 mm

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

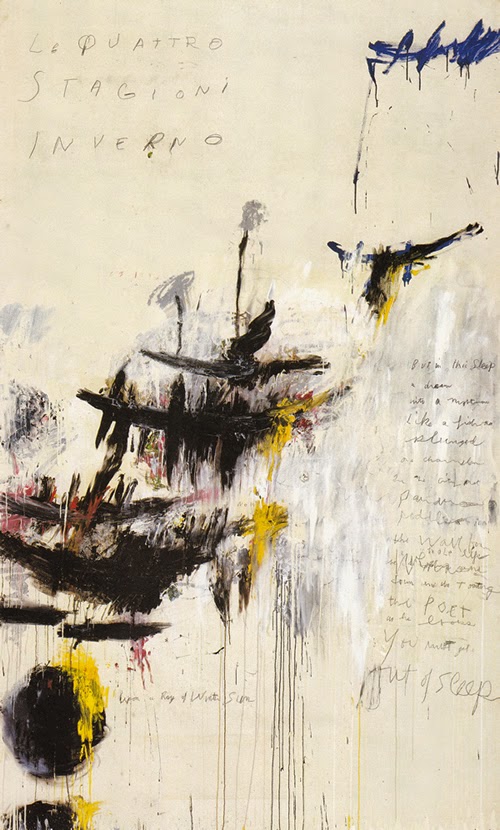

QUATTRO STAGIONI, PART IV: INVERNO, 1993-94

Synthetic Polymer Paint, Oil, House Paint,

Pencil and Crayon on Canvas

Dimensions: 313 X 190.1 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 313 X 190.1 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED 1970

Distemper and Canvas

Dimensions: 345,5

495,3 cm.

© CY Twombly

QUATTRO STAGION, PART II: ESTATE, 1993 - 1994

Synthetic Polymer Paint, Oil, House Paint, Pencil and Crayon on Canvas

Dimensions: 314.5 X 201 cm.

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

CORONATION OF SESOSTRIS, PANEL 3, 2000

Acrylic and Pencil on Canvas

Dimensions: 206 X 136.5 cm.

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

QUATTRO STAGIONI:

ESTATE, 1993-5

Acrylic and Pencil

on Canvas Support:

Dimensions: 3141 X 2152 X 35 mm

Frame : 3241 X 2250 X 67 mm.

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

COLD STREAM ROME,

1966

Oil Based House

Paint and Wax Crayon on Canvas

Dimensions: 200 X 252 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 200 X 252 cm

© CY Twombly

QUATTRO STAGIONI:

PRIMAVERA, 1993- 1995

Acrylic, Oil,

Crayon, and Pencil on Canvas Support:

Dimensions: 3132 X 1895 X 35 mm.

Frame: 3230 X 1996 X 67 mm.

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

QUATTRO STAGIONI,

PART III: AUTUNNO, 1993-94

Synthetic Polymer

Paint, Oil, House Paint,

Pencil and Crayon on

Canvas

Dimensions: 313.7 X 189.9 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 313.7 X 189.9 cm

© CY Twombly

CORONATION OF SESOSTRIS, PANEL 5, 2000

Acrylic, Crayon and Pencil on Canvas

Dimensions: 206 X 156.5 cm.

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

CORONATION OF SESOSTRIS, PANEL 7, 2000

Acrylic, Crayon and Pencil on Canvas

Dimensions: 201.5 X 154.5 cm.

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

PAN ( PART III ) 1980

Mixed Media on Paper

Dimensions: 76 X 57 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 76 X 57 cm

© CY Twombly

PANORAMA, 1955

Crayon and Chalk on Canvas

Dimensions: 257 X 339 cm.

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

FERRAGOSTO II, 1961, ROME

Oil Paint, Wax Crayon, And Lead Pencil on Canvas

Dimensions: 165 X 200 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 165 X 200 cm

© CY Twombly

Cy Twombly and Robert

Rauschenberg. Robert Rauschenberg, Venice 1952

LEPANTO, 2001 (PANEL

7 OF 12)

Acrylic, Wax Crayon

and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 216.5 X 311.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 216.5 X 311.8 cm

© CY Twombly

LEPANTO, 2001 (PANEL 5 OF 12)

Acrylic, Wax Crayon and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 216.5 X 311.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 216.5 X 311.8 cm

© CY Twombly

LEPANTO, 2001 (PANEL 8 OF 12)

Acrylic, Wax Crayon and Graphite on Canvas

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

LEPANTO, 2001 (PANEL 6 OF 12)

Acrylic, Wax Crayon and Graphite on Canvas

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

LEPANTO, 2001 (PANEL 4 OF 12)

Acrylic, Wax Crayon and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 216.5 X 311.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 216.5 X 311.8 cm

© CY Twombly

LEPANTO, 2001 (PANEL 3 OF 12)

Acrylic, Wax Crayon and Graphite on Canvas

Dimensions: 216.5 X 311.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 216.5 X 311.8 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED IV, 2005 (BACCHUS)

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 317.5 X 468.6 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED II, 2005 (BACCHUS)

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 317.5 X 468.6 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 317.5 X 468.6 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED III, 2005 (BACCHUS)

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 317.5 X 468.6 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED I, 2005 (BACCHUS)

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 317.5 X 417.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 317.5 X 417.8 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED 1968 - 1971

© CY Twombly

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, 2006

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 215.7 X 163.4 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 215.7 X 163.4 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, 2006

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 210.7 X 163.7 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 210.7 X 163.7 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, 2006

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 215.2 X 166.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 215.2 X 166.8 cm

© CY Twombly

THE GEEKS 1955

HOUSE PAINT, CRAYON AND GRAPHITE ON CANVAS

Dimensions: 108 X 128 CM.

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 108 X 128 CM.

© CY Twombly

LEAVING PAPHOS RINGED WITH WAVES (III), 2009

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 267.4 X 212.3 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 267.4 X 212.3 cm

© CY Twombly

LEAVING PAPHOS RINGED WITH WAVES (IV), 2009

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 267.4 X 212.3 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 267.4 X 212.3 cm

© CY Twombly

LEAVING PAPHOS

RINGED WITH WAVES (V), 2009

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 267.4 X 212.3 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 267.4 X 212.3 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED 1972

Oil Based House Paint, Wax Crayon and Lead

Pencil on Canvas

Dimensions: 79 5/8 X 102 1/2 Inches

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 79 5/8 X 102 1/2 Inches

© CY Twombly

Cy Twombly. Mario

Dondero, Rome 1962

UNTITLED, (PEONY

BLOSSOM PAINTINGS), 2007

Acrylic Wax Crayon,

Pencil on Wood

Dimensions: 252 X W: 551.9 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X W: 551.9 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, (PEONY

BLOSSOM PAINTINGS), 2007

Acrylic Wax Crayon,

Pencil on Wood

Dimensions: 252 X W: 551.9 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X W: 551.9 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, (PEONY BLOSSOM PAINTINGS), 2007

Acrylic Wax Crayon, Pencil on Wood

Dimensions: 252 X W: 551.9 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252 X W: 551.9 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, 1971

Distemper and Chalk on Canvas

Dimensions: 198 X 348 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 198 X 348 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, 2008 THREE PARTS

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 265.4 X 144.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 265.4 X 144.8 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, 2008 THREE PARTS

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 273.4 X 144.8 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 273.4 X 144.8 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, 2008 THREE PARTS

Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 275.4 X 144.3 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 275.4 X 144.3 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED, ROME 1966

Industrial Paint and Crayon on Canvas

Dimensions: 190 X 200 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 190 X 200 cm

© CY Twombly

CAMINO REAL (II), 2010

Acrylic on Plywood

Dimensions: 252.4 X 185.1 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252.4 X 185.1 cm

© CY Twombly

CAMINO REAL (III), 2010

Acrylic on Plywood

Dimensions: 252.4 X 185.1 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252.4 X 185.1 cm

© CY Twombly

CAMINO REAL (IV),

2010

Acrylic on

Plywood

Dimensions: 252.4 X 187.3 cm

© CY Twombly

Dimensions: 252.4 X 187.3 cm

© CY Twombly

UNTITLED 1968

Oil Chalk and Tempera on Cloth

Dimensions:172.7 X 215.9

© CY Twombly

Dimensions:172.7 X 215.9

© CY Twombly

Cy Twombly and Dominique de Menil at the Cy

Twombly Gallery.

Houston, Texas 1995

TIME –

LINES: RILKE &TWOMBLY ON THE NILE BY MARY JACBUS

‘Lines have a great effect

on paintings’

Cy Twombly, interviewed by Nicholas Serota 2007

Cy

Twombly’s remark that ‘lines have a great effect on painting’ resonates not

only with his graphic practice but with his relation to poetry. The importance

of the modern German poet Rainer Maria Rilke to Twombly includes the figure of

the Orphic poet and their shared interest in the ancient River Nile. Twombly’s

Egyptian series, Coronation of Sesostris, 2000, represents a late flowering of

his remarkable graphic inventiveness. Walter Benjamin’s 1917 essay, ‘Painting,

or Signs and Marks’, argues that, ‘The graphic line is defined by its contrast

to area’ as opposed to the mark (‘Mal’) and painting (‘Malerei’): ‘the realm of

the mark is a medium.’ His distinction between line and mark, drawing and

painting, is especially hard to maintain in relation to Cy Twombly: the

scribbled pencilling, the smudges and smears, are the marks of an affective

body used as a writing instrument. Where Benjamin speaks proleptically to

Twombly is in the decisive role he gives to writing, inscription, and naming,

along with the spatial marks on monuments and gravestones. ‘[T]he linguistic

word’, he writes, ‘lodges in the medium of the language of painting.’ With its

collage of quotations, inscriptions, and names, Twombly’s entire oeuvre could

be read as a retrospective commentary on this early Benjamin essay.

Modernist translation provides a second form of lineation. Benjamin’s essay on

‘The Task of the Translator’ uses the analogy of geometrical line for the

formal relation of translation to original: ‘Just as a tangent touches a circle

lightly and at but one point … a translation touches the original lightly and

only at the infinitely small point of the sense.’ Twombly is tangential in just

this way: a phrase or a line of poetry evokes a mood or jumpstarts a painting.

Not surprisingly, he mentions Ezra Pound (1885–1972) and T.S. Eliot (1888–1965)

as early influences. Pound made Modernism an age of translations, showing Eliot

how to use quotations, and providing a model for the postmodern practice of

Charles Olson (1910–1970) in the wake of Pound’s Cantos. Misunderstanding

Chinese writing as ideograms, Pound insisted on ‘the look of the characters’

without being able to read Chinese; Louis Zukofsky, knowing no Latin, tried to

‘breathe’ along with Catullus by following his sound, rhythm, and syntax.

Twombly ‘translates’ – visualises – the Odi di Orazio as pure scribble or

scansion (fig.1).

Lines and phrases – like inscriptions – create genealogies

and force fields of allusion. Twombly says he turned to the poets ‘because I

can find a condensed phrase … My greatest one to use was Rilke […]. I always

look for the phrase.’ Linked by the legacies of expatriate sensibility and high

modernism, Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) and Twombly are also drawn to the

richly sedimented Nile region. Both took trips up the Nile to escape the

European winter, like other wealthy Europeans in search of the sun. Ancient

Egypt is an assemblage of imaginary meanings and colonial expropriation,

archaeology and tourism. For Rilke, it was associated especially with poetry,

mourning, and the

cult of the dead. For Twombly (drawn to epic and historical themes as well as

lyric poetry), militarism and conquest converge at the meeting-point of Middle

East and western Mediterranean cultures. Hence ‘time-lines’.

Visible

signs of the colonial past surround modern time-travellers. The

nineteenthcentury installation of Cleopatra’s Needle – three ancient Egyptian

obelisks, shipped out to European capitals – monumentalise the connection

between European Egyptophilia and Egyptokleptia in central London, Paris, and

New York. For urban Europeans ‘Egypt’ is a composite imaginary that includes

colonial conquest as well as death and dying. Tracing the passage from Rilke’s

Orphic Egypt to Twombly’s Coronation of Sesostris 2000 – painted, like The

Battle of Lepanto series, after the first Gulf War – follows this complex

time-line. Along the way, I want to explore some of the graphic technologies –

technes of memory – that tie emotion to the line in both Rilke and Twombly: the

phonograph; the epigraph; and the ideograph.

PHONOGRAPH

Rilke

wrote that ‘we are incessantly flowing over and over to those who preceded us

and to those who apparently come after us … Transience everywhere plunges into

a deep being.’ Continuous flow, deep time, transience: this is Rilke’s opening

onto the Egyptian underworld of the Duino Elegies, which affirm the

transformation of living into dead. Rilke says of the Elegies that they evoke

‘age-old transmissions and rumours of transmissions’ belonging to the Egyptian

cult of the dead. But the ‘Lament-land’ of the Elegies, he goes on, ‘is not to

be identified with Egypt’; rather, it is only ‘a reflection of the Nile country

in the desert-clarity of the consciousness of the dead.’ The collective

consciousness of the dead, available to the living, provides his field of

allusion. Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus were written at the same time as the

Elegies, during 1922. Rilke recalls this outpouring of memorial poetry as borne

along by sails associated with his Nile voyage ten years before: ‘the little

rust-coloured sail of the Sonnets and the gigantic white canvas of the

Elegies’. The tenth and last of the Duino Elegies was completed soon after the

first of Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, the poetic ‘Tree’ that rises out of the

earth when Orpheus sings. The Lament-land of the final elegy contains the

reminiscence of temples, sepulchres, and the material cultures of death; but

partly - in a cryptic allusion – the outlines of ‘the doubly opened page of a

book’ to which the tenth elegy refers. Rilke’s Nile voyage had ended in Cairo

with his reading of the Egyptian Book of the Dead. A shadowy version of the voyage

of the dead man, following the Sun god in his journey across the sky, reappears

in the tenth elegy and surfaces in Twombly’s Coronation of Sesostris.

It

is hardly surprising that the Sonnets to Orpheus (memorialising a dead girl)

should be intertwined with the Nile of Ancient Egypt: in late nineteenth- and

early twentiethcentury studies of comparative religion, the Egyptian Osiris and

the Greek musician-poet Orpheus were often associated. But the Nile had

specifically poetic meanings for Rilke. The essay he wrote in 1912 soon after

his voyage, ‘Concerning the Poet’, recalls that the

meaning

of the poet was revealed to him on board the large sailing vessel with its

sixteen oarsmen which conveyed him up the Nile to the Island of Philae. The

crew are unreadable colonial subjects, with ‘the usual silly backshish face’,

yet he records their impersonal struggle as they row effortfully upstream

against the current. At irregular intervals, their rhythmic counting

stops and falters, and the singer at the front of the boat gives voice. This

sporadic song is Rilke’s allegory of the poet’s ‘place and effect within time’:

In him

the forward thrust of our vessel and the force opposed to us were continually

held in counterpoise – from time to time a surplus accumulated: then he sang.

The boat overcame the opposition; but what could not be overcome ... he, the

magician, transmuted into a series of long floating sounds, detached in space,

which each appropriated to himself. Whilst those about him were always occupied

with the most immediate actuality and the overcoming of it, his voice

maintained contact with the farthest distance The floating sounds of the Nile

boatman occupy the meeting point of deep time and the present: melancholy

detachment; contact with the farthest distance; the poet’s contingent relation

to time and space.

An

essay of 1919, ‘Primal Sound’, remembers the homemade phonographs of Rilke’s

classroom. A bristle traced and re-traced the mark of vibrations on a waxed

paper cylinder, producing a sound at once fluctuating and unsteady: ‘the sound

which had been ours came back to us tremblingly, haltingly from the paper

funnel, infinitely soft and hesitating and fading out altogether in places’.

This faltering and fading sound confronts its listeners with ‘a new and

infinitely delicate point in the texture of reality’, an appeal from elsewhere.

But what ‘impressed itself on [Rilke’s] memory most deeply’, he writes, was

‘the markings traced on the cylinder’ – the proto-writing of the past: ‘these

made a most definite impression’.

Rilke

was later reminded by the coronal sutures of the human skull of ‘one of those

unforgotten grooves’ in the home-made cylinder. What if the coronal sutures –

like the wavering line engraved by the needle of a phonograph – could be played

in a similar fashion? Is there any contour, he wonders, that could not be

experienced, ‘as it makes itself felt, thus transformed, in another field of

sense?’ As the techno-critic Friedrich Kittler observes, the skull’s eerie

replay would yield ‘a primal sound without a name, music without a notation’ –

in other words (his): metaphor. The trace is poetry’s ghostly techne. What is

the poet, if not a phonograph?

Rilke’s

two-part Sonnets to Orpheus contains his most sustained meditation on the

poetics of the trace. In the twenty-sixth sonnet of Part I (‘But you, divine

one, you, till the end still sounding …’), Orphic song resonates in things even

after his death:

… your

resonance lingered in lions and rocks

and in the trees and birds. There you are

singing still.

O you lost god! You unending trace!

Only because at

last enmity rent and scattered you

are we now the hearers and mouth of

Nature.

Orpheus dismembered lingers in a natural world that vibrates like

the mouth of a struck bell. The trace – ‘You unending trace’ (‘Du unendliche

Spur’) – is the sound-record of this vibration: Rilke’s Spur, or trace, rhymes

with Natur. The untranslatable paradox of Rilke’s sonnet makes song the origin

of poetry, but death the origin of its dissemination as writing.

EPIGRAPH

Roland Barthes famously wrote of Twombly: ‘His work is based not upon concept

(the trace) but rather upon an activity (tracing)’. In Twombly’s graphic

art, the trace is the record of a gesture. Barthes again: ‘line is action

become visible’. Like Olson, Twombly connects heart to line via the body.

Rilke’s phrase, ‘You unending trace’ (‘Du unendliche Spur’) provides the

subtitle of Twomby’s sculpture, Orpheus, 1979, (fig.2).

The materials are minimal, tacked together, yet the

effect surprisingly impressive in its scale – a lathe rising from an upended

plank, linked by a second curved lathe apparently suspended by its own weight.

The letters of the name ‘Orpheus’, scattered on the side of the base-board as

an epigraph, transform an assemblage of found objects into a monument for a

dismembered poet. The slender yet sturdy home-made geometry describes a line

that rises and falls as if to infinity.

Twombly’s letter-painting Orpheus, 1979 (fig.3) – the

same year as his sculpture – opens its initial O to form the basic apostrophic

sign of song, spelling out the rest of the name in Greek letters with a random,

shaky line, scattering them across an empty surface. Describing space in

Twombly’s work, Barthes uses the term ‘rare’ (Latin, rarus): ‘that which has

gaps or interstices, sparse, porous, scattered’. An earlier Orpheus, 1975

(fig.4), combines the motif of the broken line with another quotation from

Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus – the ‘ringing glass that shatters as it rings’ – in

a poignant geometry of line and smudge. The broken sapling of Twombly’s

Untitled sculpture of 1987 (fig.5) contains another Orphic reference to the

first of Rilke’s Sonnets (‘There rose a tree’). On the pedestal is a small sign

bearing an epigraph from the tenth and last of Rilke’s Duino Elegies: ‘And we

who have always thought of happiness climbing, would feel the emotion that

almost startles when happiness falls.’

Resisting the term ‘graffiti’ (‘naughty or

aggressive’ protest) that is often applied to his work, Twombly says that,

‘it’s more lyrical … in the totality of the painting, feeling and content are

more complicated, or more elaborate than say just graffiti.’ Barthes suggests

that Twombly’s impossible calligraphy invokes ‘what one might call writing’s

field of allusions’ – a cultural field as well as feeling and content; a long

way from a fine hand. His writing is also epigraphic, in the double sense of

alluding to the object or surface on which it is written, and requiring to be

deciphered like an ancient inscription. Twombly’s illegible scrawls and

polyglot, non-standardised capitals, his interweaving of phrases from high

modernist European poets and names from the Graeco-Roman tradition, evoke the

longue durée of a commemorative culture that reaches back to Egypt and beyond:

cult as well as culture.

Twombly playfully self-identifies with the bucolic

poet of the lyric tradition: ‘I am Thyrsis of Aetna, blessed with a tuneful

voice’ (Thyrsis, 1977). A 1968 photograph has him in the same shepherd’s pose,

leaning against a tree, as the reproduction of Cima’s Orpheus that hung over

Rilke’s desk while he was composing the Orpheus sonnets. Much has been made of

Twombly’s graphic and sometimes playful self-signing.

The collage of Apollo and the Artist, 1975 (fig.6),

for instance, contains Twombly’s ideograph for the artist: a lotus-flower

tribute that punningly alludes to w, W, or the Greek letter (w) in his own

name. The lotus combines multiple meanings – the drug that makes the expatriate

Odysseus forget his homeland, the sacred flower of ancient Egypt, source of

Nilotic fertility and symbol of natural cyclicity. But the collage contains

other inscriptions: ‘the space between’ and ‘infinite space’ (as well as ‘the

artist’, ‘Poetry’, ‘Muses’, and its scribbled measurements). The gap between

Apollo and the poet lies in the interstitial and material space that separates

these layered and contingent surfaces.

Twombly is not an artist of transcendence. His metric

is human. He associates his great Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the

Shores of Asia Minor) painting of 1972–94 (figs.7–8), with ‘life’s

fleetingness. It’s a passage.’ This is at once an expatriate’s farewell and a

nostos: ‘I found the idea of Asia Minor extremely beautiful. Saying goodbye to

something and coming back on a boat.’ Who among his American compatriots, he

wonders, had ever heard of ‘Asia Minor’? (Not so since the first Gulf War). His

vast sixteen-metre triptych performs a silent dialogue with Rilke’s ninth

elegy: ‘this fleeting world, which in some strange way / keeps calling to us.

Us the most fleeting of all.’ Faced with life’s disappearance and the

intensities of its local and human meanings, Rilke’s wanderer brings back, not

a handful of earth, but ‘some pure word, the yellow and blue / gentian’: the

words for everyday things – house, pitcher, fruit-tree – and the brilliance of

colour in things.

Say Goodbye …, abandons a region of colour, moving

from right to left, from the eastern Mediterranean into emptiness and pallor.

Catullus is returning to Italy after the death of his brother. Erotic

explosions fade, the scribbled ships of Catullus’s homebound ships diminish in

the distance, lost in European mists or the white light of the sea. Scattered

in the whiteness are letters and fragments of poetry that include the letters

of Orpheus’s name. As pointed out by Richard Leeman, who has written

extensively on the artist, Twombly’s galleys also contain the doomed Argonauts

of George Seferis, the modern Greek poet: ‘Their souls became one with the oars

and the oarlocks / with the solemn face of the prow … The companions died one

by one’. For Seferis, whom Twombly elsewhere quotes in a painting for a dying

friend named Lucio (alluding to the light-ships of poetry), and again in

Quattro Stagioni, farewell to the shores of Asia Minor would have meant the

expulsion of Greek refugees from Asia Minor after the defeat of 1922: the

restless wanderings of exiles, or today’s economic migrants, washed up on the

Italian shore.

IDEOGRAPH

The

boat ideograph in Twombly’s painting – a form of self-quotation – is a figure

for passage and exile, voyaging and nostos, death and imperial decline. More

prosaically, it alludes to the commercial rowboats and sailboats that both

Rilke and Twombly would have seen on the modern Nile. The prototype is a small

‘Celtic’ boat (oars and mast) photographed by the artist himself (fig.9).

Twombly

spent the winter in Egypt during 1984–5, staying in the Old Winter Palace at

Luxor, watching the boats go by with their cargoes. He was inspired by funeral

objects in the Cairo Museum, where he would have seen objects like the funerary

barge intended to ship the soul to its afterlife. He might also have seen the

perfectly preserved and recently excavated solar barge of King Khufo in its

museum setting.

Winter’s

Passage: Luxor, 1985 (fig.10), achieves its intimation of mortality with a few

stacked pieces of wood: distressed paint, driftwood-like components – two

boards, one curved at prow and stern, the other flat on its plinth. The poet

David Shapiro calls Twombly’s sculptures ‘toys for broken adults’, saluting

their simplicity and pathos. The boat seems to glide, carrying its weightless

freight, at once a prosaic cargo of today and the shrines transported across

the river to the temple of Osiris at Abydos. Is the ship moving or arrested?

The critic David Sylvester observes that the oblique line of the stick is both

boatman and mast: ‘where the stick’s angle is acute, there is a feeling of

serene onward movement, where it is obtuse, a feeling of uncanny stillness’. At

once in transit and suspended in time, it serves as a symbolic memento for the crossing

from the land of the living on the eastern shore of the Nile to the city of the

dead on its western shores.

Twombly’s

ten-part Coronation of Sesostris, 2000, is the culminating synthesis of his

ship ideographs and whirling expeditionary chariots: a blazing, triumphal

departure that burns itself out on the far side of the Nile. Begun in Gaeta and

completed in Virginia, it combines deceptive simplicity with painterly

sophistication and poetic adaptation. Twombly calls this multi-media series

(drawn, written, painted) one of his favourite sets and ‘very personal’. It

incorporates a poem of 1996 by the Southern poet Patricia Waters, not a

translation this time, although its title (‘Now is the Drinking’) translates

Nunc est bibendum (fig.11). With a few strokes and deletions, Twombly

‘interprets’ the poem to create his own reticent version:

A

When they leave,

Do

you think they hesitate,

Turn and make a farewell sign,

Some gesture of

regret?

A

When

they leave,

the music is loudest,

the sun high,

A

and

you, dizzy with wine

befuddled with well-being,

sink into your body

as though

it were real,

as if yours to keep.

A

You

neither see their going,

nor hear their silence.47

A

Either

side of this ambiguous celebration of bodily oblivion, Twombly’s sequence

tracks the energetic course of the Pharaonic conquerer, Sesostris II.

Herodotus

records that Sesostris, whose name means ‘man of valour’, set up pillars

displaying emblems of female genitalia in the cities he conquered to humiliate

their inhabitants. An artist of the sexual image (like Twombly), Sesostris

consists of a collage of inscriptions, hoaxes, myths, and desires. The huge

canvases of Coronation of Sesostris chart the arc of a single day, from sunrise

to journey’s end. His coronation is his passing, as the solar bark burns its

way across the sky. A rudimentary child’s crayon sun rises hugely, then takes

the form of the sun-god’s triumphant wheeled chariot (Twombly’s ideograph for

military conquest), ushering in the solar bark of Sesostris (figs.12, 13). A

fluid sunburst of colour accompanies the half-obscured lines from Sappho that

reappear

again

at the end of the sequence: ‘Eros, weaver [of myth]’, ‘Eros, sweet and bitter,

Eros bringer of pain’ (fig.14). The glaring sun shines remorselessly, high in

the sky (fig.15). Next comes the ceremonial barge, dripping with splendour and

yellow and alarazin (crimson) rosettes of paint (fig.16).

Twombly’s

‘interpreted’ poem, ‘When the gods depart’ – gorgeously decorated with his late

Mannerist explosions of crimson flowers or liquid fireballs (fig 17) – serves

as a hinge between the flaming barge and its dissolution into a burnt-out

skeleton (fig.18). The scrawled text provides an epigraph for the series:

‘they’ (the gods) are leaving, glorious but unheeded, as the mortal body sinks

into oblivion, scarcely registering their passing. Nunc est bibendum: sorrows

are drowned, the boat is a drunken boat, the poem a scribbled memo-to-self, a

scarcely legible scrawl with its bursts and drips of paint. The blazing barge

dissolves into its own reflection, melting into shadowy, Turneresque

reflections in an exquisite coalescing of self-quotation and reminiscence as it

sinks beneath the waves (figs.19, 20). With the burnt-out stick-ship, the

ideograph becomes minimal, like the shadowy Celtic boat, the canvas emptied of

colour, the writing undulating and (literally) vague: ‘leaving Paphos ringed

with waves’ (fig.20). 51 Twombly’s farewell to Eros and the good life

quotes, not Archilochos (general and mercenary, as Twombly recalls), but the

late Bronze Age poet-warrior, Alkman, who survives only in fragments and

phrases. The lines announce a departure from Cyprus (island of love) and

Paphos, sacred to Aphrodite: ‘Leaving Kypros the lovely /And Paphos ringed with

waves.’ The solar journey comes to an abrupt halt with a monumental endstop,

and a now-legible epigraph: ‘Eros, weaver of Myth … Eros bringer of pain’

(fig.21). The Gods have departed, along with love. The western bank of the Nile

with its blockish steps and temple confronts the viewer with a non-negotiable

step into the 53 unknown. The ascending step motif or metric, present in other

Twombly paintings and drawings, surfaces as an indecorous quotation of the

silhouetted top-hat in Degas’s painting Cotton Exchange in New Orleans

(fig.22): ‘So how it got in there, I don’t know’. Perhaps Twombly’s eye was

drawn to the dazzling commerce in whiteness at the heart of Degas’s picture. He

is, after all, a Southern painter.

Seferis’s

‘An Old Man on the River Bank’, written in exile in British-occupied Cairo in

1942, considers ‘towards what we go forward’: not as he hears ‘the companions

calling from the opposite shore’ but ‘in some other way’. He summons up the

present-day Nile as it moves forward in time and space, between its greenery

and ordinary Arab lives, and ‘great tombs even and small habitations of the

dead’. Seferis’s old man turns away from the past, since song is sinking

beneath its own weight, and art eaten away by gold: Because we’ve loaded even

our song with so much music that it’s slowly sinking and we’ve

decorated our art so much that its features have been

eaten away by gold:

B

Because we’ve loaded even our song with so much music

that it’s slowly sinking

and we’ve decorated our art so much that its features have

been eaten away by gold

and it’s time to say our few words because tomorrow our

soul sets sail.

B

In a

vertiginous flashback, he remembers how ‘a life that was as it should be’

became dust, ‘and sunk into the sands / leaving behind it only that vague

dizzying sway of a tall palm tree’. Seferis’s poem of passage anticipates

Twombly’s late work, its magnificence and melancholy along with its flowering

into new forms of graphic and mnemonic invention: the way his line sways

vaguely and dizzyingly across the canvas, carrying its freight of emotion along

with its reminder that the body exists in time, not apart from it.

http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/10/time-lines-rilke-andtwombly-on-the-nile

CY TWOMBLY – BIOGRAPHY – CHRONOLOGICAL NOTES

Cy Twombly was born in Lexington,

Virginia, on 25th April 1928 to parents from New England.

1942 - 1946

The most influential person on his formative

years was the Spanish artist Pierre Duara who had come to Lexington from Paris

for the duration of the war. Twombly attended his painting classes and lectures

on Modern European Art for four years starting when he was fourteen years old.

1946 - 1949

Graduated from Lexington High School and

attended Darlington School in Rome, Georgia. Spent the summer of 1947 in

Ogunquit, Maine (an art colony that existed at the time) In the autumn of 1947

enrolled at the Boston Museum School, attending night classes the first year

and day school in the second. During the late forties Twombly's main interests

were German Expressionism, the Dada movement, Schwitters' as well as Soutine's

work. Saw for the first time reproductions of works by Dubuffet and Giacometti

which greatly impressed him.

1949 - 1951

Returned to Lexington, Virginia, to enter

Washington and Lee University where an art department had opened that year.

Continued his studies at the Art Students League in New York City in 1950 on a

tuition scholarship. During the second semester met Robert Rauschenburg who was

the first person of his own age to share the same interests and preoccuptions

as an artist. In New York city he saw shows of Pollock, Rothko, Newman, Still,

Motherwell and others at Betty Parsons' and at the Kootz Gallery, and for the

first time de Kooning's and Kline's work at the Egan Gallery. Spent the summer

and winter semester of 1951 at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. During

the summer Ben Shahn and Robert Motherwell were artists in residence. In

November 1951 Twombly had his first one-person exhibition at The Seven Stairs

Gallery in Chicago of paintings done at Black Mountain College that summer. The

show was arranged by the photographer Aaron Siskind and the curator Noah

Goldowsky. First exhibition in New York arranged by Robert Motherwell at the

Kootz Gallery.

You

may read entire biography in choronological history to click above link.

,+2008.jpg)

,+2008.jpg)

,+2008.jpg)

,+2008.jpg)

+GAETA,+2008.jpg)

+GAETA,+2008-1.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

..jpg)

,+2009.jpg)

,+2007-1.jpg)

,+2007.jpg)

,+2007-2.jpg)

,+2010.jpg)