ITALIAN FUTURISM:

1909 – 1944: RECONSTRUCTING THE UNIVERSE

SOLOMON R.

GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM

February 21, 2014 - September

1, 2014

ITALIAN FUTURISM: 1909 – 1944: RECONSTRUCTING THE UNIVERSE

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM

February 21, 2014 - September 1, 2014

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum presents Italian Futurism, 1909 -

1944: Reconstructing the

Universe, the first comprehensive overview in the United States of one of

Europe’s most important 20th-century avantgarde movements. Featuring over 360

works by more than 80 artists, architects, designers, photographers, and

writers, this multidisciplinary exhibition examines the full historical breadth

of Futurism, from its 1909 inception with the publication of Filippo Tommaso

Marinetti’s first Futurist manifesto through its demise at the end of World War

II. The exhibition includes many rarely seen works, some of which have never

traveled outside of Italy. It encompasses not only painting and sculpture, but

also the advertising, architecture, ceramics, design, fashion, film, free-form

poetry, photography, performance, publications, music, and theater of this

dynamic and often contentious

movement that championed modernity and insurgency.

The exhibition is organized by Vivien Greene, Senior Curator, 19th-

and Early 20th-Century Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. An international

advisory committee composed of eminent scholars from many disciplines provided

expertise and guidance in the preparation of this thorough exploration of the

Futurist movement, a major modernist expression that in many ways remains

little known among American audiences.

The Leadership Committee for Italian Futurism, 1909 - 1944: Reconstructing the Universe is also gratefully acknowledged

for its generosity, including the Hansjörg Wyss Charitable Endowment; Stefano

and Carole Acunto; Giancarla and Luciano Berti; Ginevra Caltagirone; Massimo

and Sonia Cirulli Archive; Daniela Memmo d’Amelio; Achim Moeller, Moeller Fine

Art; Pellegrini Legacy Trust; and Alberto and Gioietta Vitale.

ABOUT FUTURISM

Futurism was launched in 1909 against a background of growing

economic and social upheaval. In Marinetti’s “The Founding and Manifesto of

Futurism,” published in Le Figaro, he

outlined the movement’s key aims, among them: to abolish the past, to champion

modernization, and to extol aggression. Although it began as a literary

movement, Futurism soon embraced the visual arts as well as advertising,

fashion, music and theater, and it spread throughout Italy and beyond. The

Futurists rejected stasis and tradition and drew inspiration from the emerging

industry, machinery, and speed of the modern metropolis. The first generation

of artists created works characterized by dynamic movement and fractured forms,

aspiring to break with existing notions of space and time to place the viewer

at the center of the artwork. Extending into many mediums, Futurism was

intended to be not just

an artistic idiom but an entirely new way of life. Central to the

movement was the concept of the opera d’arte totale or “total work of art,” in

which the viewer is surrounded by a completely Futurist environment.

More than two thousand individuals were associated with the

movement over its duration. In addition to Marinetti, central figures include:

artists Giacomo Balla, Benedetta (Benedetta Cappa Marinetti), Umberto Boccioni,

Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, and Enrico Prampolini; poets and writers

Francesco Cangiullo and Rosa Rosà; architect Antonio Sant’Elia; composer Luigi

Russolo; photographers Anton Giulio Bragaglia and Tato (Guglielmo Sansoni);

dancer Giannina Censi; and ceramicist Tullio d’Albisola. These figures and

other lesser-known ones are represented in the exhibition.

Futurism is commonly understood to have had two phases: “heroic”

Futurism, which lasted until around 1916, and a later incarnation that arose

after World War I and remained active until the early 1940s.

Investigations of “heroic” Futurism have predominated and

comparatively few exhibitions have explored the subsequent life of the

movement; until now, a comprehensive overview of Italian Futurism had yet to be

presented in the U.S. Italian art of the 1920s and ’30s is little known outside

of its home country, due in part to a taint from Futurism’s sometime

association with Fascism. This association complicates the narrative of this

avant-garde and makes it all the more necessary to delve into and clarify its

full history.

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

Italian Futurism unfolds

chronologically, juxtaposing works in different mediums as it traces the myriad

artistic languages the Futurists employed as their practice evolved over a

35-year period. The exhibition begins with an exploration of the manifesto as

an art form, and proceeds to the Futurists’ catalytic encounter with Cubism in

1911, their exploration of near-abstract compositions, and their early efforts

in photography. Ascending the rotunda levels of the museum, visitors follow the

movement’s progression as it expanded to include architecture, clothing,

design, dinnerware, experimental poetry, and toys.

Along the way, it gained new practitioners and underwent several

stylistic evolutions—shifting from the fractured spaces of the 1910s to the

machine aesthetics ( or arte meccanica ) of the ’20s, and then to the softer,

lyrical forms of the ’30s. Aviation’s popularity and nationalist significance

in 1930s Italy led to the swirling, often abstracted, aerial imagery of

Futurism’s final incarnation, aeropittura. This novel painting approach united

the Futurist interest in nationalism, speed, technology, and war with new and

dizzying visual perspectives. The fascination with the aerial spread to other

mediums, including ceramics, dance, and experimental aerial photography.

The exhibition is enlivened by three films commissioned from

documentary filmmaker Jen Sachs, which use archival film footage, documentary

photographs, printed matter, writings, recorded declamations, and musical

compositions to represent the Futurists’ more ephemeral work and to bring to

life their words-in-freedom poems. One film addresses the Futurists’ evening

performances and events, called serate, which merged “high” and “low” culture

in radical ways and broke down barriers between spectator and performer.

Mise-en-scène installations evoke the Futurists’ opera d’arte totale interior ensembles, from those

executed for the private sphere to those realized under Fascism. Italian

Futurism concludes with

the five monumental canvases that compose the Syntheses of Communications ( 1933 – 34 ) by Benedetta (

Benedetta Cappa Marinetti ), which are being shown for the first time outside

of their original location. One of few public commissions awarded to a Futurist

in the 1930s, the series of paintings was created for the Palazzo delle Poste

(Post Office) in Palermo, Sicily.

The paintings celebrate multiple modes of communication, many

enabled by technological innovations, and correspond with the themes of

modernity and the “ total work of art ”

concept that underpinned the Futurist ethos.

http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/press-room/releases/5708-guggenheim-museum-presents-unprecedented-survey-of-italian-futurism-opening-in-february

You may read whole manifesto from to click below link Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum's web page.

http://exhibitions.guggenheim.org/futurism/manifestos/

GERARDO DOTTORI - AERIAL BATTLE OVER the GULF of NAPLES or

INFERNAL BATTLE OVER the PARADISE of THE GULF - 1942 (DETAIL)

GERARDO DOTTORI - AERIAL BATTLE OVER the GULF of NAPLES or

INFERNAL BATTLE OVER the PARADISE of THE GULF - 1942

INFERNAL BATTLE OVER the PARADISE of THE GULF - 1942

Oil on Plywood Panel

Dimensions: 187 x 131 cm.

Private collection

Dimensions: 187 x 131 cm.

Private collection

© 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Luca Carrà

AEROPITTURO

The swirling, sometimes abstracted, aerial imagery of Futurism’s

final incarnation, aeropittura ( painting inspired by flight ),

arrived by the 1930s. Aeropittura emerged from the Futurists’

interest in modern aircraft and photographic technologies. Propelled by Italy’s

military preeminence in aviation, their fascination with the machine shifted

focus from the automobile to the airplane. In flight the artists found

disorienting points of view and new iconographies to explore in painting,

photography, and other mediums.

Evidenced by the work of Tullio Crali, Gerardo Dottori, and

Tato, aeropittura represented a novel painting approach that

allowed the Futurists to address nationalism, speed, technology, and war,

providing radical perspectives that exalted these concepts. Benito Mussolini

equated his Fascist regime with the Roman Empire at its peak; not

coincidentally, many artworks from the 1930s incorporated imagery from Roman

antiquity. Tato’s Flying over the Coliseum in a Spiral ( Spiraling ) (1930)

depicts an airplane soaring over an iconic Italian structure, the circles of

the plane’s path echoing the ancient building’s form. The Futurists’ engagement

with the aerial quickly expanded beyond painting to other fields, including

ceramics, dance, and experimental photography.

http://exhibitions.guggenheim.org/futurism/aeropittura/index.html

TULLIO CRALI - BEFORE THE PARACHUTE OPENS 1939 DETAIL

TULLIO CRALI - BEFORE THE PARACHUTE OPENS 1939

Oil on Panel

Dimensions: 141 x 151 cm.

Casa Cavazzini, Museo d' Arte Moderna a Contemporanea, Udine, Italy

© 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome

Photo: Claudio Marcon, Udine, Civic Musei E Gallerie di Storia e Arte

Oil on Panel

Dimensions: 141 x 151 cm.

Casa Cavazzini, Museo d' Arte Moderna a Contemporanea, Udine, Italy

© 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome

Photo: Claudio Marcon, Udine, Civic Musei E Gallerie di Storia e Arte

TULLIO CRALI UPSIDE DOWN LOOP ( DEATH LOOP ) 1938 DETAIL

TULLIO

CRALI, UPSIDE DOWN LOOP ( DEATH LOOP ) 1938

Oil on Panel

Dimensions: 80 x 60 cm.

Collection of Luce Marinetti, Rome

Dimensions: 80 x 60 cm.

Collection of Luce Marinetti, Rome

© 2014 Artists Rights SocietyNew York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Studio Boys, Rome

TATO GUGLIELMO SANSONI - FLYING OVER THE COLISEUM IN A SPIRAL 1930

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 80 x 80 cm.

Ventura Collection, Rome . Photo: Corrado De Grazia

PIERO BOCCARDI - COVER OF CATALOGUE FOR EXPERIMENTAL

EXHIBITION of FUTURIST PHOTOGRAPHY - 1931

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 23.9 x 17.3 cm.

Collection of Giorgio Grillo, Florence

Dimensions: 23.9 x 17.3 cm.

Collection of Giorgio Grillo, Florence

TATO GUGLIELMO SANSONI, FANTASTICAL AEROPORTRAIT of MINO SOMENZI 1934

Photomontage, Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 24 x 18 cm.

Rovereto, MART, Archivio del ’900,

Dimensions: 24 x 18 cm.

Rovereto, MART, Archivio del ’900,

Fondo Mino Somenzi. Photo: © MART, Archivio del ’900

FILIPPO MASOERO - DESCENDING OVER SAINT PETER CA.

1927–37

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 24 x 31.5 cm

Touring Club Italiano Archive

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 24 x 31.5 cm

Touring Club Italiano Archive

PHOTOGRAPHY

Inspired by Henri Bergson’s philosophical ideas on dynamic

movement, in late 1911 the Futurist painters began to freely adapt the

photographic motion studies of French biophysicist Etienne - Jules Marey and

Anglo-American photographer Eadweard Muybridge. Seeking to revitalize painting,

Futurist Anton Giulio Bragaglia worked with his brother Arturo Bragaglia, an

accomplished photographer, to develop a method of capturing movement they

called photodynamism. The pictures on which the Bragaglia brothers collaborated

plot the movement of a figure, usually from right to left, with intermediary

sections of motion blurred.

Despite their proclaimed interest in new technologies, the

Futurists largely neglected photography after these early experiments until the

1930s. In the 1930 “Futurist Photography: Manifesto,” F. T. Marinetti and Tato

declared photography to be a powerful tool in the Futurist effort to eliminate

barriers between art and life. With the camera, they could explore both “pure”

art and art’s social function. Also a designer, graphic artist, and painter,

Tato was a leader in Futurist photography and used the camera for diametrically

opposed goals; his works express his ideological support of the Fascist regime

and reflect his engagement with the absurd.

Futurist photography exhibitions of the 1930s presented avant-garde

images that not only reveal an awareness of international modernist currents

but also demonstrate strategies specific to the Italians. Futurist photographic

techniques include the layering of multiple negatives, perspectival

foreshortening, and photomontage. While the 1930s exhibitions included

photographs by Bragaglia, the manifesto suggested that the newer photographers’

superimpositions achieved a simultaneous representation of time and space that

moved beyond Bragaglia’s photodynamism.

The 1930s also saw the merging of photographic technology with

other Futurist art forms, especially dance, painting, and performance inspired

by mechanized flight. Meanwhile, photographers Filippo Masoero and Barbara

developed novel conceptions of space by photographing Italian cities from an

airplane’s cockpit.

http://exhibitions.guggenheim.org/futurism/photography/index.html

ANTON GIULIO BRAGAGLIA - THE TYPIST - 1911.

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 11.9 x 16.7 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Gilman Collection, Gift of the Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

Dimensions: 11.9 x 16.7 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Gilman Collection, Gift of the Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

© 2014 Artists Rights Society , New York / SIAE, Rome

Image source: Art Resource, New York © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

ANTON GIULIO BRAGAGLIA – WAVING – 1911 DETAIL

ANTON GIULIO

BRAGAGLIA – WAVING – 1911

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 17.5 x 23 cm.

Galleria Civica di Modena, Italy

Dimensions: 17.5 x 23 cm.

Galleria Civica di Modena, Italy

© 2014 Artists

Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Francesca Mora

MARIO BELLUSI,

MODERN TRAFFIC IN ANCIENT ROME 1930

Photomontage,

Gelatin Silver Print

Dimensions: 15

x 20 cm.

Rovereto,

MART, Archivio del ’900, Fondo Mino Somenzi.

Photo:

© MART, Archivio del ’900

GINO SEVERINI - BLUE DANCER – 1912

Oil on Canvas With Sequins,

Dimensions: 61 x 46 cm.

Gianni Mattioli Collection, on Long - Term Loan to

Dimensions: 61 x 46 cm.

Gianni Mattioli Collection, on Long - Term Loan to

the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

© 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / ADAGP, Paris

GINO SEVERINI - BLUE DANCER – 1912 (DETAIL)

HEREOIC FUTURISM

The years leading up to World War I are often called Futurism’s “heroic” phase. In this era colored by optimism, the Futurists worked in a mature avant-garde language; their compositions edged toward abstraction and they reinvented traditional artistic forms. The group also acquired members beyond the initial Milan–Rome axis. In Florence, for example, Giovanni Papini and Ardengo Soffici became involved with the movement. Their journal Lacerba (1913–15) published history-making exchanges on Futurism.

Futurist visual artists agreed that the representation of dynamism and simultaneity was tantamount, but were divided on how to achieve this. Giacomo Balla examined trajectories of movement. The Iridescent Interpenetrations, which are thought to illustrate light’s movement in electromagnetic waves, are his attempt to portray the universal dynamics that permit speed. These explorations informed his later Abstractions of Speed, a series prompted by the reflections of passing cars in shop windows. Balla realized his own visual vocabulary for velocity by combining the Futurist principles of dynamism and simultaneity with allusions to light, sound, and smell. On the other hand, Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini sought to represent the distorting effects of motion on a subject. Boccioni looked to the action of the athletic body, merging figure and ground in his activated renderings of a rider on a galloping horse and of a cyclist racing through a landscape. Severini’s exposure to Parisian cafes, cabarets, and dance halls compelled him to study movement through dance, painting fragmented, whirling forms.

Revolutionary literary and architectural experiments also occurred in these years. The Futurists pioneered a style of visual poetry they called parole in libertà, or “words-in-freedom.” Introduced by F. T. Marinetti, words-in-freedom was seized upon in the 1910s by Futurist painters and writers who produced confrontational, unorthodox sketches (tavole parolibere) on modern themes. In 1914 the architects Mario Chiattone and Antonio Sant’Elia each created a series of utopian (and unrealized) designs for the contemporary city. Incorporating new materials and accommodating rapid transport, they reenvisioned urban existence through a vanguard aesthetic based on technology.

CARLO CARRA

FUNERAL OF THE ANARCHIST GALLI 1910 - 1911 (DETAIL)

CARLO CARRA

FUNERAL OF THE ANARCHIST GALLI 1910 - 1911

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 198.7 x 259.1 cm

Credit: Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange)

© 2019 Carlo Carrà / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York /

SIAE, Rome

UMBERTO BOCCIONI, STATES of MIND 1911

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979.

Those Who Stay - 1911.

Oil on canvas, 70.8 x 95.9 cm.

Oil on canvas, 70.8 x 95.9 cm.

© The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York

UMBERTO BOCCIONI, STATES of MIND 1911

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979.

From top: The Farewells - 1911.

Oil on Canvas, 70.5 x 96.2 cm;

Those Who Go - 1911.

Oil on canvas, 70.8 x 95.9 cm;

Oil on Canvas, 70.5 x 96.2 cm;

Those Who Go - 1911.

Oil on canvas, 70.8 x 95.9 cm;

Those Who Stay - 1911.

Oil on canvas, 70.8 x 95.9 cm.

Oil on canvas, 70.8 x 95.9 cm.

© The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York

UMBERTO BOCCIONI, STATES of MIND 1911 (DETAIL)

UMBERTO BOCCIONI, STATES of MIND 1911

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979.

Those Who Go - 1911

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 70.8 x 95.9 cm

© The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 70.8 x 95.9 cm

© The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York

UMBERTO BOCCIONI, STATES of MIND 1911

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979.

From top: The Farewells - 1911.

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 70.5 x 96.2 cm

© The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 70.5 x 96.2 cm

© The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York

GIACOMO BALLA - AUTOMOBILE IN CORSA 1913

LUIGI RUSSOLO - SOLIDITY of FOG - 1912

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 100 x 65 cm.

Gianni Mattioli Collection, on long-term loan to

Dimensions: 100 x 65 cm.

Gianni Mattioli Collection, on long-term loan to

the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, used by permission

GIACOMO

BALLA, PATHS of MOVEMENT + DYNAMIC SEQUENCES 1913

Tempera on Paper, Mounted on Canvas

Dimensions: 49 x 68 cm.

Dimensions: 49 x 68 cm.

Gianni Mattioli Collection, on Long - Term Loan

to

the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

© 2014 Artists Rights Society , New York / SIAE, Rome

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM FOUNDATION DESIGN BY FRANK LLOYD WRITE

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM

FRANK LLOYD

WRIGHT • ESTABLISHED IN 1939 • BUILT IN 1959

An

internationally renowned art museum and one of the most significant

architectural icons of the 20th century, the Guggenheim Museum in New York is

at once a vital cultural center, an educational institution, and the heart of

an international network of museums. Visitors can experience special

exhibitions of modern and contemporary art, lectures by artists and critics,

performances and film screenings, classes for teens and adults, and daily tours

of the galleries led by museum educators. Founded on a collection of early

modern masterpieces, the Guggenheim Museum today is an ever-evolving

institution devoted to the art of the 20th century and beyond.

ARCHITECTURE

In 1943, Frank

Lloyd Wright was commissioned to design a building to house the Museum of

Non-Objective Painting, which had been established by the Solomon R. Guggenheim

Foundation in 1939. In a letter dated June 1, 1943, Hilla Rebay, the curator of

the foundation and director of the museum, instructed Wright, “I want a temple

of spirit, a monument!”

Wright’s

inverted-ziggurat design was not built until 1959. Numerous factors contributed

to this 16-year delay: modifications to the design (all told, the architect

produced 6 separate sets of plans and 749 drawings), the acquisition of

additional property, and the rising costs of building materials following World

War II. The death of the museum’s benefactor, Solomon R. Guggenheim, in 1949

further delayed the project. It was not until 1956 that construction of the

museum, renamed in Guggenheim’s memory, finally began.

Wright’s

masterpiece opened to the public on October 21, 1959, six months after his

death, and was immediately recognized as an architectural icon. The Solomon R.

Guggenheim Museum is arguably the most important building of Wright’s late career.

A monument to modernism, the unique architecture of the space, with its spiral

ramp riding to a domed skylight, continues to thrill visitors and provide a

unique forum for the presentation of contemporary art. In the words of critic

Paul Goldberger, “Wright’s building made it socially and culturally acceptable

for an architect to design a highly expressive, intensely personal museum. In

this sense almost every museum of our time is a child of the Guggenheim.”

Wright’s

original plans for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum called for a ten-story

tower behind the smaller rotunda, to house galleries, offices, workrooms,

storage, and private studio apartments. Largely for financial reasons, Wright’s

proposed tower went unrealized. In 1990, Gwathmey Siegel & Associates

Architects revived the plan with its eight-story tower, which incorporates the

foundation and framing of a smaller 1968 annex designed by Frank Lloyd Wright’s

son-in-law, William Wesley Peters.

In 1992, after

a major interior renovation, the museum reopened with the entire original

Wright building now devoted to exhibition space and completely open to the

public for the first time. The tower contains 4,750 square meters of new and

renovated gallery space, 130 square meters of new office space, a restored

restaurant, and retrofitted support and storage spaces. The tower’s simple

facade and grid pattern highlight Wright’s unique spiral design and serves as a

backdrop to the rising urban landscape behind the museum.

In 2008, the

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum was designated a National Historic Landmark; in

2015, along with nine other buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, the

building was nominated by the United States to be included in the United

Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage List.

HISTORY

The Solomon R.

Guggenheim Foundation was founded in 1937, and its first New York–based venue

for the display of art, the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, opened in 1939.

With its exhibitions of Solomon

Guggenheim’s somewhat eccentric art collection, the unusual

gallery—designed by William Muschenheim at the behest of Hilla Rebay, the

foundation’s curator and the museum’s director—provided many visitors with

their first encounter with great works by Vasily Kandinsky, as well as works by

his followers, including Rudolf Bauer, Alice Mason, Otto Nebel, and Rolph

Scarlett. The need for a permanent building to house Guggenheim’s art

collection became evident in the early 1940s, and in 1943 renowned architect

Frank Lloyd Wright gained the commission to design a museum in New York City.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum opened on October 21, 1959, and in 2019, celebrates 60

years as an architectural icon and “temple of spirit”

where radical art and architecture meet.

RICHARD ARMSTRONG

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM AND FOUNDATION

SOLOMON

R. GUGGENHEIM

The

collection that Solomon R. Guggenheim (1861–1949) gave to his foundation

between 1937 and his death in 1949 included hundreds of artworks from the

most vibrant and dynamic styles of European modernism, including over 150 works

by Vasily Kandinsky. The museum that bears his name was made possible by his

inspired collecting of the art of his time. Yet, notably, Guggenheim only

turned to contemporary, abstract art later in his life. He once said, “As it grew

on me . . . I wished others to share my joy.”

Solomon

Guggenheim and his wife, Irene Rothschild Guggenheim, began collecting art in

the 1890s. At first the Guggenheims collected works expected of the refined

members of the upper class: old masters, the French Barbizon school, American

landscapes, Audubon prints, and manuscript illuminations. It was not until

1927, when he was in his late 60s, that Solomon started collecting modern art,

when he met German abstract painter and collector Hilla Rebay,

whom Irene had commissioned to paint his portrait.

Rebay’s

studio near Carnegie Hall was decorated with works by artist Rudolf

Bauer, her on-and-off romantic partner and longtime artistic

collaborator. Guggenheim took an interest in these pieces—which were “nonobjective,”

as Rebay referred to them, and dramatically different from the art he had

previously experienced. The two formed a friendship, and Rebay encouraged him

to collect some works by Bauer; this was the starting point of a personal and

professional relationship that would last the rest of Guggenheim’s life.

In

1930, the Guggenheims traveled with Rebay to Europe to see, study, and collect

art—one of several such trips they would make. In Dessau, Germany, they

met Kandinsky while

he was teaching at the Bauhaus, and Guggenheim purchased Composition 8 (Komposition

8, 1923). For the remaining twenty years of his life, Guggenheim, with

Rebay’s input, systematically collected nonobjective art, purchasing works from

Bauer and Kandinsky, as well as Robert Delaunay and László Moholy-Nagy. He expanded

his collection in other aspects of modern art, with works by Marc Chagall,

Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, and Amedeo Modigliani. During this time, he also

had dealings with gallery owner Karl Nierendorf,

whose private collection would ultimately become part of the Guggenheim

Foundation’s holdings.

“I

wished others to share my joy.”

Of his

collecting at this time, Guggenheim said, “Everybody was telling me that this

modern stuff was the bunk. So as I’ve always been interested in things that

people told me were the bunk, I decided that therefore there must be beauty in

modern art. I got to feel those pictures so deeply that I wanted them

to live with me.”

Live

with him, they did. Beginning in the early 1930s, the Guggenheims used several

suites that they occupied at the Plaza

Hotel to showcase the growing collection, which was open to the

public by appointment. Guggenheim’s collection also decorated his country home

at Trilora

Court in Sands Point, Long Island.

Guggenheim

and Rebay envisioned something even greater for the collection’s display; in

1936, Rebay organized the first museum exhibition of the Guggenheim collection

at the Gibbes Memorial Art Gallery (now the Gibbes

Museum of Art) in Charleston, South Carolina, near the Guggenheim’s

farm and hunting retreat in Cainhoy. In 1937, Solomon founded the Guggenheim

Foundation with Rebay as its curator and director. Further exhibitions were

mounted at the Philadelphia Art Alliance in 1937; at the Gibbes again in 1938;

and at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1939. Rebay later recounted that

Guggenheim wanted to open a grand museum as soon as possible, but that she

encouraged him to start on a smaller scale and build an American public for

nonobjective art.

Together,

they contracted young architect William Muschenheim to design a gallery for the

Museum of Non-Objective Painting, which opened in 1939 on East 54th Street. The

unusual space corresponded to Rebay and Guggenheim’s notions of a

“museum-temple” for the deep contemplation of the spiritual and utopian aspects

of nonobjective art. It had pleated-velour-covered walls and carpeted floors,

incense filled the air, and music by Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig von

Beethoven played in the gallery. All of these elements were meant to enable the

general public to “live” with these works.

After

several years of increasing attendance for the Museum of Non-Objective

Painting, Guggenheim and Rebay commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design a

museum for a lot that Guggenheim had acquired on Fifth Avenue. The site was

just blocks from other institutions with wealthy industrialist patrons—the

Frick Collection and the Metropolitan Museum of Art—but the new museum’s

architecture and purpose were to be very different indeed. Wright’s now-iconic

spiral design opened to the public in 1959, ten years after Guggenheim’s death.

Toward the end of his life, Guggenheim said of the project that he never

regretted his “intuitive decision nor my great faith in this [nonobjective]

Art.”

Through

the institutions that he founded, Guggenheim was able to provide a public home

and ongoing preservation, archival, and curatorial support for his collection

as well as those of his colleagues and contemporaries, Rebay, Justin

K. Thannhauser, Nierendorf, Katherine

S. Dreier, and eventually, his niece Peggy

Guggenheim. Those institutions continue to collect, preserve, and

showcase the most relevant modern and contemporary movements and works from

artistic communities around the globe.

https://www.guggenheim.org/history/solomon-r-guggenheim

RICHARD ARMSTRONG

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM AND FOUNDATION

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM DESIGN BY FRANK LLOYD WRITE

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM FOUNDATION

CARLO CARRA - INTERVENTIONIST DEMONSTRATION 1914

Tempera, Pen, Mica Powder, Paper Glued on Cardboard

Dimensions: 38.5 x 30 cm

Gianni Mattioli Collection, on Long - Term Loan to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection,

Venice © 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome

Photo: Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Dimensions: 38.5 x 30 cm

Gianni Mattioli Collection, on Long - Term Loan to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection,

Venice © 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome

Photo: Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

CARLO CARRA - INTERVENTIONIST DEMONSTRATION 1914 (DETAIL)

WORDS IN FREEDOM

In one of their pivotal inventions, the Futurists conceived a style of free-form, visual poetry called parole in libertà, or “words-in-freedom.” Following F. T. Marinetti’s example, the Futurists liberated words and letters from conventional presentation by destroying syntax, using verbs in the infinitive, eliminating adjectives and adverbs, abolishing punctuation, inserting musical and mathematical symbols, and employing onomatopoeia. Words-in-freedom poems were read as literature, experienced as visual art, and performed as dramatic works. The Futurists published them in multiple formats and declaimed them at the Futurist serate (performative evenings).

While Marinetti introduced the form, many Futurists contributed their own interpretations. A group of pictorially, verbally, and aurally imaginative sketches for words-in-freedom (called tavole parolibere) originated in the revolutionary period of the 1910s. Giacomo Balla invented phonovisual constructions, while Fortunato Depero devised an abstract language of sounds he called onomalingua. Francesco Cangiullo’sLarge Crowd in the Piazza del Popolo (1914) engages the themes of the city, the crowd, and upheaval. The circular structure of Carlo Carrà’s Chronicle of a Milanese Night Owl (1914) captures the sensory whirlwind of voices, sounds, and figures he encountered during a nocturnal walk in Milan.

http://exhibitions.guggenheim.org/futurism/words_in_freedom/index.html

BENEDETTA CAPPA MARINETTI - SPICOLOGIA OF 1 MAN - 1919

India Ink on Paper

Dimensions: 16 × 16 cm.

Private collection © Benedetta Cappa Marinetti,

Dimensions: 16 × 16 cm.

Private collection © Benedetta Cappa Marinetti,

Used by permission of Vittoria Marinetti and Luce Marinetti's heirs.

Photo: Luca Carrà

Photo: Luca Carrà

F. T. MARINETTI - AIR RAID ( n. 67 ) 1915 - 1916

Ink and Pencil on Paper

Dimensions: 21.5 x 27.5 cm.

Collection of Luce Marinetti, Rome

Dimensions: 21.5 x 27.5 cm.

Collection of Luce Marinetti, Rome

© 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Studio Boys, Rome

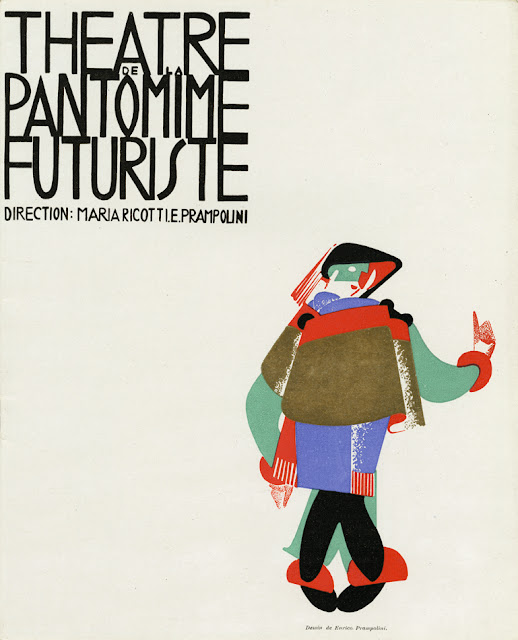

ENRICO PRAMPOLINI and MARIA RICOTTI,

WITH COVER by ENRICO PRAMPOLINI 1927

Program For the Theater of Futurist Pantomime

Illustrated Leaflet (Paris: M. et J. De Brunn ),

Dimensions: 27.5 x 22.7 cm

Fonds Alberto Sartoris, Archives de la Construction

Moderne–Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland -

Photo: Jean-Daniel Chavan

WITH COVER by ENRICO PRAMPOLINI 1927

Program For the Theater of Futurist Pantomime

Illustrated Leaflet (Paris: M. et J. De Brunn ),

Dimensions: 27.5 x 22.7 cm

Fonds Alberto Sartoris, Archives de la Construction

Moderne–Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland -

Photo: Jean-Daniel Chavan

FRANCESCO CANGIULLO - LARGE CROWD in THE PIAZZA DEL POPOLO 1914

Watercolor, Gouache, and Pencil on Paper

Dimensions: 58 x 74 cm

Private collection © 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome

FILIPPO TOMMASO MARINETTI

In The Evening, Lying on Her Bed, She Reread the

Letter From Her Artilleryman at the Front 1919 (Detail)

FILIPPO TOMMASO MARINETTI

In The Evening, Lying on Her Bed, She Reread the

Letter From Her Artilleryman at the Front 1919

F. T. MARINETTI - ZANG TUMB TUUUM: ADRIANOPLE OCTOBER 1912;

Words-in-Freedom Book ( Milan: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, 1914 ),

Dimensions: 20.2 x 14 cm.

Dimensions: 20.2 x 14 cm.

The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

© 2014 Artists Rights Society New York / SIAE, Rome

GIACOMMO BALLA - TRELSI. . . . TRELNO – 1914

Ink on Paper

Dimensions: 27 x 20 cm.

Private collection © 2014 Artists Rights Society

Dimensions: 27 x 20 cm.

Private collection © 2014 Artists Rights Society

New York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Luca Carrà

FRANCESCO CANGIULLO – PIEDIGROTTA - 1916

Book ( Milan: Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia ),

Dimensions: 26.5 x 18.8 cm.

Dimensions: 26.5 x 18.8 cm.

The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

© 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome

BENEDETTA CAPPA MARINETTI

BENEDETTA CAPPA MARINETTI - SYNTHESIS of AERIAL COMMUNICATIONS 1933–34

Tempera and Encaustic on Canvas

Dimensions: 324.5 x 199 cm

Il Palazzo delle Poste di Palermo, Sicily, Poste Italiane

© Benedetta Cappa Marinetti, used by Permission of Vittoria Marinetti

and Luce Marinetti’s heirs - Photo: AGR / Riccardi / Paoloni

GIACOMO BALLA - THE HAND OF THE VIOLINIST - 1912

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 56 x 78.3 cm

Estorick Collection, London

© 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome

FORTUNATO DEPERO - HEART EATERS - 1923

Painted Wood

Dimensions: 36.5 x 23 x 10 cm

Private collection © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS),

New York / SIAE, Rome - Photo: Vittorio Calore

Painted Wood

Dimensions: 36.5 x 23 x 10 cm

Private collection © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS),

New York / SIAE, Rome - Photo: Vittorio Calore

MINO SOMENZI, ED., WITH WORDS-in-FREEDOM

IMAGE AIRPLANES by PINO MASNATA

Futurismo 2, no. 32 (Apr. 16, 1933) - Journal (Rome, 1933),

Futurismo 2, no. 32 (Apr. 16, 1933) - Journal (Rome, 1933),

Dimensions: 64 x 44 cm

Fonds Alberto Sartoris, Archives de la Construction Moderne–Ecole Polytechnique

Fonds Alberto Sartoris, Archives de la Construction Moderne–Ecole Polytechnique

Fédérale de Lausanne EPFL), Switzerland - Photo: Jean-Daniel Chavan

LUIGI RUSSOLO “ THE ART of NOISES: FUTURIST MANIFESTO ” 1913

Wolfsoniana - Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

By permission of heirs of the artist - Photo: Courtesy Wolfsoniana

Wolfsoniana - Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

By permission of heirs of the artist - Photo: Courtesy Wolfsoniana

Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

FUTURISTIC RECONSTRUCTION OF THE UNIVERSE

In 1915 Giacomo Balla and Fortunato

Depero wrote the seminal manifesto “Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe.”

Using characteristically aggressive language, they call for a reenvisioning of

every aspect of the world, even demanding Futurist “toys.” These ideas fed the

Futurist conception of the opera d’arte

totale (total work of art), an ensemble that surrounds the

viewer in a completely Futurist environment. Balla, Depero, and others soon put

their ideas into practice, opening case d’arte (art

houses) to market their decorative arts designs. Balla converted his home in

Rome into a showroom of sorts, designing nearly everything in the residence.

Depero established an artisanal studio in his native town of Rovereto. Balla

made screens, which often shared concerns with his speed-related paintings, and

other furniture. Both artists designed waistcoats that reflect the aesthetics

of their paintings. Depero fashioned his brightly colored vests expressly for

the Futurists to wear with their bourgeois suits to signal their radicalism.

Balla conceived a coffee service (recalling his 1916 sketches for a tea set)

that was produced in majolica in Faenza in 1928, and many other Futurists

experimented with ceramics, especially in the 1930s. Some Futurist artists

secured commissions to design elaborate interiors for homes, restaurants, and

cabarets.

http://exhibitions.guggenheim.org/futurism/futurist_reconstruction_of_the_universe/#5

ANTONIO SANT’ELIA - STATION FOR TRAINS and AIRPLANES 1914

Pencil and Ink on Paper

Dimensions: 27.9 x 20.9 cm.

Pinacoteca Civica di Como, Italy

Dimensions: 27.9 x 20.9 cm.

Pinacoteca Civica di Como, Italy

Photo: Courtesy Musei Civici Como

ARCHITECTURE

The Futurists celebrated the modern city. Rejecting historicism and seeking to revolutionize urban life, architects Mario Chiattone and Antonio Sant’Elia proposed utopian visions for cities of the future in two series of drawings: Buildings for a Modern Metropolis and Città Nuova (both 1914). Embracing new materials and industrial methods that would alleviate the need for internal load-bearing systems, these designs feature soaring, narrow structures outfitted with thin, lightweight facades. External elevators and viaducts shoot up the spare, windowless planes. The Futurist emphasis on speed is accommodated by unimpeded transportation systems, including facilities for both air and rail travel (see Sant’Elia’s Station for Trains and Airplanes and Tullio Crali’s later plan for a similar center). While Chiattone never defined himself as a Futurist, Sant’Elia outlined the goals of this style in a text that was subsequently edited by Marinetti and issued as “Futurist Architecture: Manifesto” ( 1914 ). These early forays into architecture stressed rhetoric rather than execution and pictorial imaginings took precedence over the specifics of implementation. Sant’Elia died in World War I in 1916 and Chiattone moved in another direction, and their Futurist designs were never built.

By the 1930s, the Fascist state was erecting new public buildings in the clean, spare parlance of Rationalism or the Stile Littorio (which references classical Roman architecture). Neither the complex modern metropolis envisioned by architects such as Chiattone and Sant’Elia nor the theatrical urban buildings dreamed up by Virgilio Marchi were realized. Their successor, Alberto Sartoris, also built few of his designs, and he vacillated between Futurism and Rationalism, exhibiting the same plans under both banners. While he aligned himself with Futurism conceptually, he leaned toward functionalist aesthetics. Sartoris’s axonometric projections eschew superfluous forms in favor of structures that alternate massed volumes with empty space. Crali, better known as a visual artist, also imagined modern envelopes for practical structures, as in his multipurpose Sea Air Rail Terminal. Among the few Futurist structures to be built were temporary ones for fairs, such as those conceived by the multifaceted artist Enrico Prampolini.

http://exhibitions.guggenheim.org/futurism/architecture/index.html

VIRGILIO MARCHI

- BUILDING SEEN FROM A VEERING AIRPLANE 1919–20

Tempera on Canvased Paper

Dimensions: 130 x 145 cm.

Private collection, Switzerland

Dimensions: 130 x 145 cm.

Private collection, Switzerland

VIRGILIO MARCHI - BUILDING SEEN FROM A VEERING AIRPLANE (DETAIL)

TULLIO CRALI, SEA AIR RAIL TERMINAL:

MARINE CENTER WITH MOORING BASIN 1930

MARINE CENTER WITH MOORING BASIN 1930

India Ink on Paper

Dimensions: 32 x 52.5 cm.

Dimensions: 32 x 52.5 cm.

MART, Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, Italy.

Photo: © MART, Archivio Fotografico

GIACOMO BALLA - BALBO AND THE ITALIAN TRANSATLANTIC FLYERS - 1931

Oil on Panel

Dimensions: 280 x 150 cm.

Museo Storico dell’Aeronautica Militare, Rome

Dimensions: 280 x 150 cm.

Museo Storico dell’Aeronautica Militare, Rome

© 2014 Artists Rights Society - New York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Massimo Napoli

THE FUTURIST & THEIR

CONTEMPORIES

The Futurists

had been a long time formulating their theories and were determined to maintain

their identity by standing firm in the storms of innovation that were sweeping

over the art world. While all the Futurists agreed to this separation, it was

upheld especially by those best informed about the international

scene—Marinetti, Severini, and Boccioni. Severini had moved to Paris in 1906,

and he had become the link between the Futurists and the artistic and cultural

world outside Italy. He moved in the circles that championed the most

avant-garde tendencies and knew many literary figures. He would marry the

daughter of Paul Fort, the prime despoètes, and Apollinare, Max Jacob, Blaise

Cendrars, Braque, Picasso, Raoul Dufy, and Suzanne Valadon were among his

friends. In 1910 Severini accepted his friend Boccioni's invitation to sign the

first Manifesto of Futurist Painters and thenceforth kept the band informed of

the latest news in Paris through long letters which remain of great interest.

In 1911, during their first officiai showing as a group (an exhibition held in

Mìlan in the former premises of the Ricordi music publishers), they were

vigorously attacked by Ardengo Soffici, the Fiorentine champion of Cubism who

accused them of using worn-out forms and iconography made irrelevant by the

Cubists. Soffici's articles in the review La Voce about Picasso, Braque, and

the other Cubists stirred the newly formed group to confront the French

challenge. For the Futurists the renewal of Italian culture was a matter of

international as well as national import. To break through the limitations of a

vocabulary stili tied to a pronounced idealism, they needed to under stand just

what their artistic rivals were up to. The theoretical texts they wrote cìearly

distinguished their aesthetic from that of the Cubists, a definition that was

as necessary for their development as for the public's.

The first

significant contact with Cubist ideas carne from a lengthy letter that Severini

wrote to Boccioni in 1911. It read in part: "The most modem [painters] can

be divided into Cubists, Picassoans, and Independents. I give the latter that

name because I don't know what other to give a number of individuai who propose

to turn out painted canvases following only their minds' impulses but with

neither aim nor direction. They say they don't want to confuse their fellow

creature by giving him the illusion of something true by means of paint. When

they have produced a nude woman, for example, they say: 'This is canvas and

these are the colors, but I did not set out to produce a laughing woman or,

better, I made this woman as my brain wished it and not as my eyes and everyone

else's have seen her in life.' In landscapes some of them attempt to present

trees and houses from the greatest possible number of sides; indeed, their aim

is to present objects from ali sides, and in that they are in direct contact

with the Cubists but with the difference that the Cubists resolve the problem

directly by showing half the object in perspective and the other half

immediately alongside, sectioned like an engineer's blueprint, whereas these

others compose bizarre perspectives that at the most give the impression of

seeing the objects in a bird's-eye view from above. Those who strictly speaking

are Cubists do not even know why they are called thus. Perhaps it is because of

the geometrie forms that predominate in their pictures. Their endeavor is

certainly heroic but infantile. I allude to the goal they have set themselves

to achieve: painting an object from several sides or dissected. The engineers

have resolved that question in a more complete fashion, and there is no need to

go back to it. Some Cubists become decorators and caricaturists, but then their

sincerity is open to doubt."

Severini

distinguishes between the Cubists and Picassoans by explaining, according to

his own point of view, how much the process of abstraction practiced by Picasso

and

Braque

differs from the self-styled Cubists* fanciful and even arbitrary tricks of

perspective. (This distinction between Picassoans and Cubists, with the latter

term reserved for painters like Metzinger, Gleizes, Le Fauconnier, and Lhote,

refleets the general criticai position of the time.) His observations sum up

the polemics that raged around the Salon des Indépendants which opened at the

end of April 1911. In Room 41, the focus of much heated debate, there were

works by Le Fauconnier, Gleizes, Metzinger, and Delaunay, all of them artists

strenuously defended by Apollinaire in the pages of L'intransigeant. In an

article published on April 21 the poet stressed the force of these works and

the modernity of their style, though with out denying that they looked very

much stripped down to basics and sometimes overly rigid. All of these artists

made an obvious effort to solve the problem of reducing and concentrating form,

a problem Picasso and Braque had resolved with a considerably greater intensity

of synthesis. But the latter pair demonstrated an aristocratic aloofness in

their refusai to participate in the officiai exhibitions, and in any case during

this period their efforts were increasingly concentrated on issues of

spatiality and on the dialectic between image and reality.

Since 1910

Severini had been living at 5 Impasse Guelma in Montmartre, the same building in

which Braque had his studio. There he observed his French colleague's

development firsthand and discussed the problems that had concerned him for

some time, notably the relation between form and movement that was the

cornerstone of the Futurist aesthetic.

Severini

wrote further: "If you say to them that a chair has no inherent movement,

they reply that because man can impart one to it, they consider [the chair] as

a thing endowed with movement. However, sometimes they fix on an object

constituting part of the picture, for example, a dice cube or a drawer handle,

and they put a good deal of emphasis on that detail. If you ask them why, they

will tell you that a die does not have the same movement as a drinking glass or

a bottle or a chair; and if you tell them that this affirmation is purely

gratuitous and is a rather obvious contradiction, they reply: 'There are so

many things like that that one can't explain!' And then they pretend they are

not intuitive! Some of their theories come fairly dose to our truths. For

example: If you look at a man, you can see him circumscribed within a definite

plastic form because now you have to see him in connection with all the

movements he can make and in all the deformations resulting from the movements.

Yet they do not accept that one can give the impression of movement by giving a

man in motion more arms or more legs, because by that means one would arrive at

most at an impressionistic physical truth to the detriment of the plastic and

pictorial point of departure

which, for them, is the same as that adopted by the masters, from Rembrandt

right up to Corot. "

"In

front of one of his pictures," Severini went on, "I made Braque

confess that his art was in principle descriptive, and once I got this

assertion out of him I pointed out that by the force of things it became

anecdotal. And so very anecdotal that to depict a table you use the kind of

walnut stain sold in corner paint shops and applied to ordinary soft wood to

make it look like walnut. And the same for ebony and rosewood. In that way, he

says, it works out to be much simpler and less arty. "

The young

Futurist was trying strenuously to grasp the basic principles of the Cubist method, but

the significance of the structural intuition Braque and Picasso relied on

eluded him, as did their fundamental credo that their images had nothing to do

with empirical reality. He did, however, recognize the importance of their

efforts to simplify forms and to render the image in simultaneous views. He saw

too that, while the paintings of Braque and Picasso were strikingly similar in

this period, each painter was in fact exploring entirely different aspects.

Picasso aimed at his own kind of pictorial truth by confronting the problems of

spatiality and looking deeply into the reality of the objects he represented.

Braque was more concerned with the relation between things and colors, and he

concentrated more on the problem of their relationship with the space around

them (whence the charge of illusionism that Severini brought against his

paintings).

Severini

continued: "They make a show of a great distaste for the nobility of

colored material and for painting in general. When I tried to remind Braque

that the Greeks insertedhairs into a sculptured head to create a beard, he said

that he himself was following thisprinciple but that the Greeks had turned away

from it because they aimed at an expression of beauty whereas he did not wish

his painting to be beautiful. . . . This exaggerated repugnance of theirs for

beauty has an explanation in something their friends told me: It seems they are

convinced and fervent Christians. For that reason they make use of the humblest

materials in order to enhance a kind of intimate modest beauty, something

perhaps inherent in them [the materials]; this constitutes their ultimate goal

in art, quite outside any contemporary metaphysical problem."

Severini's

reference to the placement of a realistic element, convincingly naturalistic in

appearance, into an obviously unrealistic context is of special interest, above

all in light of the

future development of both Cubism and Futurism and the revolutionary innovation

of collage. Even more significantly it anticipates the introduction of

real-life materials into sculpture which Boccioni himself would practice

beginning in 1912.

Severini's

long letter reveals the gulf that, from the outset, separated Futurist and

Cubist aesthetics. On the one hand, Futurist painting: compounded out of light

and color, based on the dynamic decomposition of forms—forms broken down not

for analysis of their structure and components but in consequence of their

motion in space and the associated emotion—and accentuated by a fierce and

pure-toned coloring. On the other, Cubist painting: exploration of tonai

modulations conceived in relation to the forms as such. While the Futurists'

approach was based on the harsh clash of pure colors and a palette emphasizing

complementary colors, Braque and Picasso looked to analogies of tones, not

contrasts, within a limited variety of colors. "I should like my colors to

be diamonds," Severini wrote, echoing an idea developed at length in the

Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting of Aprii 11, 1910, "and to be

able to use them abundantly so as to make my pictures more dazzling with light

and richness. Before siding once and for ali against Picasso and his comrades,

I want to continue the analysis of them and their works. Certain of their

theories appear to have a good deal of truth in them and cannot be condemned a

priori: Indeed, certain of them are indisputable truths. The only thing is, I

am not in rapport with their artistic expression.

"In a

portrait, they say, there is no need to work out exactly the physical harmony that exists

between the eyes, the nose, and the mouth, but one does need to understand the

moral link between those details of the face; and that moral harmony can be

understood and must be conveyed despite all the deformations imprinted on them

by movement. If you tell them that they are drifting into caricature, they

reply that their deformations are in rapport with their conception of what a

picture is, that is, quite outside the physical harmony everybody understands

and sees, whereas in caricature the nose is always placed beneath the eyes and

the mouth beneath the nose." But "moral harmony" was exactly

what the Futurists were denying in this first phase of their activity.

"The art

of the Cubists," Severini observed, "beginning with Léger and up to

Le Fauconnier and Metzinger traces no new path nor will it leave any trace

despite the numerous imitators and the few admirers. They are stili too

attached to the bygone laws of plasticity to enter into the field of abstract

painting or purely metaphysical expression. In fact, in some of their canvases

they do not go beyond Impressionism, applying it to communicate some anecdote

or other. They have their origin in Derain whose figures without chiaroscuro

(Matisse fashion) seem to glorify the grotesque, but a deliberate and

consciously infantile grotesque. The Cubists say they base their work on the

ethics of Corot, but they follow the aesthetics of Cézanne. "

This passage

anticipates Guillaume Apollinaire's affirmation in Les Peintres Cubistes (1913) that

André Derain was the real precursor of the Cubist aesthetic. But while Derain

pursued a course that began with the study of Cézanne and would lead him in

about 1906 to concentrate on the transposition of forms, he never analyzed

subjects structurally. Yet both Severini and Apollinare seem to have intuited

that Derain's particular approach played a fundamental part in the discovery of

the aesthetic possibilities of African art, its primitive imagery and its

reduction to essentials. Certainly Apollinaire and Severini saw much of each

other in 1911 and may well have exchanged opinions on the burning issues of the

day.

As Severini

saw it, "only Picasso and Braque, who only recently broke with the

Cubists, have a formidable, new boldness. They truly take as little as possible

from nature and break away from ali the laws of art accepted till today. They

do not paint forms and colors but sensations, and because of their total

renunciation of the laws of art, I believe they are closer to literature than

to painting. In fact, if it is true that artistic expression needs to be

liberated from atavistic slavery to form, and that form must be subjected to

ali the sensations and deformations due both to movement and to the almost

simultaneous succession of different impressions on the retina, it is also true

that (to remain in the field of painting) certain artistic principles must be

retained to reveal the cause of the sensation the painter expresses. Those

principles are moreover exclusively intuitive, and therefore often confuse the

sensation with the cause that produced it. And perhaps this is why those two

artists, and Picasso in

particular, are often suspected of bluffing, and their sincerity is questioned

by the majority of people. They can also be accused of being one-sided because

both of them, with an identical manner of coloring and with the same rhythm

ofline, always express the same sensation.

"Be that

as it may, they are the most interesting artists of our age, and their art is

one of our Futurist verities. . . . One needs to be grateful to the Cubists for

the formidable slap in the face they have given the Academy and the public that

enjoys commonplace expressions that cali for no effort. They aspire to lead the

public toward a new aesthetic and in that respect are admirable. They want no

more landscapes with dazzling colors. Nature is too materially beautiful and

kind to the eye. To our tormented souls ali that healthy delight in color and

line is as irksome as the laughter of children amusing themselves while we are

gnawed by doubt. If a modem painter wishes to spare modem spirits, who seek new

and profound sensations in art, the noisome impression of that importunate

laughter, he must garner in

life other beauties than the physical ones of color and form; color and form should no

longer exist save in the guise of sensations and not as goal in themselves.

Here is our point of contact with the truth of Braque and Picasso, whom I

classify with the name of neo-artists. "

When Boccioni

received Severini's long letter he had very likely not yet written the text for

the lecture he would give in May 191 1 at the Circolo Artistico in Rome.

Certainly his friend's ideas and his highly detailed descriptions of the

current innovations in the Paris art world must have come as a boon. The

letter, along with Soffici's article on Braque and Picasso in La Voce, must

have played a large part in persuading Boccioni to make a sorde to the French

capital, which he did in October.

A previously

unpublished letter (now in the Museum of Modem Art, New York) by Boccioni

dated October 15, 1911, indicates that he arrived in Paris some ten days after

the Salon d'Automne opened: "I have already seen the modem painters who interested

me. I will continue to study them, but I see that I had already intuited

virtually everything about them and it is merely a certain outward look they

have (due to the enormous incredible influence of Cézanne and Gauguin and

others) that makes the ideas of some of them appear more daring than they

really are. Of the Cubists I have not yet seen Picasso, Braque, and a few

others. Of those I have seen—Metzinger, Fauconnier, Léger, Gleize [sic], etc.

—only the first is really venturing into an unexplored field . . . but what

metaphysics!! Everything I myself have done in the way of metaphysics (physical

transcendentalism) is stili something of an absolute reality ...

"It is strange how

nothing, absolutely nothing, has escaped me of what goes to make up the complex

of aspirations of the finest modem painting! I say strange because, thinking of

Italy, I marvel that I haven't died there of drowning …. And now that I am

about to touch shore I think with infinite tenderness of the person who helped

me keep afloat in that sad sea of social and intellectual mediocrity which is

Italy today! I have a great longing to return. I have to work like a madman,

even if it kills me, but it is sad to think that I will have to spend my entire

life sweeping up Italy's trash and refuse! Here I am extremely well known among

the young artists and my incognito under my mother's name Forlani has given me

a lot of amusement.

"At the

Bai de la Gaiette last evening word got around among a band of Italian painters that

I was there, and throughout the evening they ali buzzed about our group.

Finally one of them carne up to me and asked if I was Boccioni. I replied yes

but that having left in Italy ali my ideas about painting, I wanted to have a

rest and avoid all discussion. There were introductions, and a Genoese painter

with a horrific look of bohème poured out ali his woes to me .... The young

man ruling the roost here now is Picasso. There is much talk about him, and the

dealers put his tiniest and most insignificant pen-and-ink sketches in their

Windows in huge sumptuous and even antique frames and, underneath, with great

ostentation: Picasso(\). It is a real and marvelous launching, and the painter

scarcely finishes a work before it is carted off and paid for by the dealers in

competition with each other."

Boccioni had

been in Paris only two days but had already seen the works of most of the

Cubists who interested him. His first reaction was defensive. He claimed he had

already intuited what the artists were up to from Severini's description; this

was not an idle boast, as can be seen in the text of the lecture he had given

five months earlier. His letter indicates that the indebtedness to Cubism some

find in him has been asserted much too strongly and at times too uncritically.

Cubism was, of course, extremely important in the forging of the Futurist

aesthetic, but it is also true that for years Boccioni had been developing new

ideas that only needed to be put to the test—therein lies the importance of his

trip to Paris in the fall of 1911.

This was not

Boccioni's first visit. He had been in Paris for a few months in 1906 when he

was overwhelmed by the look and feel of that great city. Rome had a population

of five hundred thousand—a village compared to the Parisian megalopolis.

"Think of the thousands of carriages," he wrote to his family on

April 17, 1906, "and the hundreds of omnibuses, horse-drawn, electric, and

steam-driven trams, all double-deckers, and the motorized taxicabs in the streets;

think of the Metropolitan, an electrified railway that runs under all of Paris

and the tickets are bought by going down into great underground places entirely

illuminated by electric light; the ferry boats, exactly like those in Venice

and always packed with people. It is something simply past believing. In the

midst of all this movement put thousands of bicycles, lorries, carts and

wagons, private automobiles, delivery bicycles …. The streets are full of

advertisements; signs even on the roofs; cafés by the thousands all with tables

outside and all of them packed; in the midst of all this three million souls

who rush about wildly, run, laugh, who work out deals, and so on and so on as

much as you want ….

"I have

seen women such as I never imagined could exist! They are entirely painted:

hair, lashes,

eyes, cheeks, lips, ears, neck, shoulders, bosom, hands and arms! But painted

in a manner so marvelous, so skillful, so refined, as to become works of art.

And note that this is done even by those of low station. They are not painted

to compensate for nature; they are painted for style, and with the liveliest

colors. Imagine: hair of the most beautiful gold topped by little hats that

seem songs in themselves—marvelous! The face pale, with a pallor of white

porcelain; the cheeks lightly rosy, the lips of pure Carmine shaped clearly and

boldly; the ears pinkish; the neck, nape, and bosom very white. The hands and

arms painted in such a way that everyone has very white hands attached by the

most delicate wrists to arms lovely as music" (Birolli 1971, pp. 332-38).

In October

1907 Boccioni again visited Paris, this time for a week. When he returned to

Milan, he was exhausted and racked by doubt. He was seized by violently

religious and metaphysical emotion and felt impelled to delve into the depths

of the spiritual and physical worlds. Between late 1909 and early 1910 the

discouraged young artist met the self-styled "caffeine of Europe,"

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, poet by trade and firebrand by inclination. The

encounter infused Boccioni with a new vitality. While the works he produced at

that portentous moment of his life do not depart from traditional pictorial

formulas, they push to an extreme a Divisionism marked by intense color and

complex brushwork.

With the

parturition of the Futurist movement the troubled artist would suddenly win

greater assurance. He would throw himself into a life outside his narrow world,

open himself to

the risks of unrestrained emotion. He would move ever further away from a

traditional conception of form and, at last, venture into the exploration of

himself and his art that he had been contemplating for years. In 1910, when he

began work on The City Rises (no. 50), he would declare that he had meditated

on the idea of the picture for four full years, that he had worked painfully

and obsessively on that whirling frenzy of colors which, originai as it is,

stili bears the stamp of a markedly Symbolist approach.

For years he

had been pondering the problem of how to represent modem life, and it was in

large measure the contact with the great urban world of Paris that finally

moved him to create more modem, more timely expressive forms. The adventure of

Futurism, launched in 1910 with an intense theoretical program formulated in

its manifestos, unleashed the twenty-eight-year-old's pent-up aggression. For

ali the new movement's determination to stir up an Italy stili dreaming of its

past, Paris was the artistic heart and center of the world, and Paris would be

the Futurists' touchstone and lodestar.

When Boccioni

went off to Paris in October 1911, he was already pondering the ideas that

underlie States of Mind (no. 56), the canvases he completed in the months just

before they were shown at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune. If Boccioni's conception

was tainted by a certain evocative Symbolism, it nonetheless already involved a

dynamic element that is unrelated to the Cubists' frigid and static optic. The

works by Le Fauconnier and Gleizes that Boccioni saw at the Salon d'Automne and

mentioned in his letter were perhaps too descriptive for the budding Futuristi,

and Léger's canvas had in fact been criticized by Apollinare as a modest

product of a stili unripe pei sonality. Room 8 in the exhibition which housed

those artists had been dubbed "Cubist" by the poet-critic who made

much of the fact that they had now truly taken on the character of a school. In

Room 8 there were also works by the brothers Marcel Duchamp and Jacques Villon

whose acquaintance Boccioni would make a few months later on the occasion of

the Futurist exhibition at the Galerie Bernheim Jeune. Duchamp was then working

on Nude Descending a Staircase, a painting which, criticized by Gleizes, would

be refused by the Salon des Indépendants in March 1912.

In Souvenirs:

Le Cubisme 1908-1914, the memoirs he wrote during World War II, Gleizes

recalled the excitement of the exhibition opening: "The ensemble no longer

presented the homogeneity ofRoom 41. The representatives of orthodox Cubism—Le

Fauconnier, Léger, Metzinger, and myself—found themselves side by side with

artists having only remote resemblances to them, who did not have the same

point of departure and who would for a long time or forever deny any connection

with Cubism. ... In any case, despite that lack of homogeneity, the ensemble had

a fine provocative air about it. In those painters one sensed an air of battle.

. . . Very curious, that rush of visitors denser in that year of 1911 than in

earlier years because they had been alerted by items in the newspapers

announcing the participation of the 'Cubists' whose appearance, six months

earlier, had been a surprise."

Boccioni

arrived in Paris just as the new movement was taking off. Picasso and Braque,

who did not choose to show with the other artists, were not, however,

classified as Cubists, and in fact Gleizes and Picasso would not meet until

after the inauguration of the Salon d'Automne. Boccioni declared that the

artist who impressed him most was Jean Metzinger, because his theoretical

position was both more advanced and clearer than that of the other Cubists

(Picasso and Braque as always excepted). Metzinger had published articles on

the relationship between the new art and the classical tradition and, in

addition, called for a "totality" in painting that would synthesize

all possible views of the object represented. Apollinaire's review of the Salon

d'Automne stressed Metzinger 's richness of imagination and profound

culture, noting that he had finally shaken off the influence of Picasso so conspicuous

in his earlier paintings. His compositional structures, once very similar to

Picasso's, were now being simplified and resolved in a manner less volumetrie

and more confined to the picture surface. Unlike works from the same time by

the first Cubists, his paintings treat the decomposition of the image without

aiming at three-dimensionality. He emphasized instead the intersection of

planes without overly stressing the feeling of form. In Metzinger's works of

this period there is a certain effort at abstraction, but he stili appears the

most naturalistic of the Cubist group. The abstraction of the forms, which may

have been what appealed to Boccioni in Metzinger's work, was based on very

different values from his. For Boccioni the new form and the new color, as he

had proclaimed in his lecture of the preceding May, must arise out of the

emotion aroused by the subject itself.

Boccioni met

Apollinaire in the fall of 1911. "I have not yet seen any Futurist

pictures, " the critic wrote in the Mercure de France in November,

"but if I have understood correctly the

point of the new Italian painters' experiments they are concerned above all

with expressing feelings, virtually states ofthe soul (this is an expression

used by M. Boccioni himself), and with expressing them in the most forceful

manner possible. These young people also desire to move away from naturai forms

and claim to be the inventors of their art." With a tone of half-amusement

half-irony Apollinaire also made much of Severini's whim of wearing socks of

different colors. Fernande Olivier, Picasso's mistress at the time, also

mentioned this detail and described Boccioni's first meeting with Picasso:

"During the winter after the return from Céret—Picasso had spent the

summer of 1911 there together with Braque working in isolation—the Italian

Futurists burst upon Montmartre convoyed by Marinetti whom Apollinaire was

simply dotty about. Naturally enough they carne to Picasso's. Severini as well

as Boccioni who died in the war were hot-headed fanatics who dreamed of a

Futurism dethroning Cubism. They made a great thing out of their professions of

faith …. They tried to give themselves bizarre airs, attempting to stand out

physically at least, to create a sensation, but their means were mediocre and

they often made themselves ridiculous.

Boccioni and Severini, leaders among the painters, had inaugurated a Futurist

fashion which consisted in wearing two socks of different colors but that

matched their ties" (Olivier 1933).

Even before

their introductory exhibition the young Futurists elbowed their way into the Parisian art

scene spoiling for a fight. To impress that (presumably) hostile (or merely

indifferent?) world, no weapon was neglected: rhetoric, dialectic, debate,

demonstrations, unmatched socks. No surprise then that these foreign artists

were greeted with a certain wariness. If nothing else, with their theories and

their pictures (it is difficult to say which were more disturbing) they were

introducing stili greater confusion into a situation already far from

clear-cut. Having prepared a bumpy way for themselves, they made their officiai

bow before the Parisian public in February 1912. The preface to the catalogue

of their show at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune was written in the aggressive

language characteristic of their manifestos. Though the preface was signed by the

Futurist quintet Boccioni, Carrà, Russolo, Balla, and Severini, a note made it

clear that the ideas expressed had been propounded by Boccioni in his lecture

ofMay 1911. The stand they took against the Cubists was harsh and unequivocal,

and their shrill tone antagonized critics and artists alike.

From their

first programmatic pronunciamentos the Futurists had brandished the banner of

Modernism. The time, they announced, was overripe for new aesthetic canons, and

they were prepared to invent them. Modernism called for new and regenerating

ideas, for broadly comprehensive images for which reality was a source

of inspiration but not the measuring rod. The Futurists were the first to

declare the aesthetic of the machine and of speed as the single ali-decisive principle

for a cultural ideology. In his lecture of 1911 Boccioni had grappled with the

dilemma ofhow one could represent modem life. To be truly modem a work of art

had to mirror the urgent and relentless rhythms of the new times, had to strip

away every trace of concern with the object as such which had made fleeting

phenomena cold and lifeless.

Theories

not with standing, in the works Boccioni showed in Paris the relationship with reality

was stili very strong and was rendered in a contradictory manner. The objective

fact, the given, the point of departure constantly broke through to the fore no

matter how it was swept along in the impetus of the movement and deformed by

force-lines. The Futurists' extrovert art, which shone—glared—with violent

colors and swift, aggressive images was completely different from the

introverted experiments of the Cubists who conceived of a work of art as an

object in itself whose form obeyed no laws outside itself. With their tense

straining toward the future and toward a modem ideal, the Futurists transformed

the very meaning of the object, while for the Cubists the object was a stable

point on which to build their reflective vision.

The theory of