MIRA SCHENDEL AT TATE MODERN LONDON

September 25, 2013 – January 19, 2014

MIRA SCHENDEL AT TATE MODERN LONDON

September 25, 2013 – January 19, 2014

Tate Modern is to stage the first ever international,

full-scale survey of the work of

Mira Schendel (1919-1988) from 25 September 2013. Schendel

is one of Latin America’s most important and prolific post-war artists.

Alongside her contemporaries Lygia Clark and Helio Oiticica, Schendel

reinvented the language of European Modernism in Brazil. The show exemplifies

how Tate is continuing to rethink and re-present the history of modern and

contemporary art by showing artists who established their careers outside

Europe and the USA.

The exhibition will bring together over 300 paintings,

drawings and sculptures from across her entire career, many of which have never

been exhibited before. Highlights include her Droguinhas ( Little Nothings ) 1965-6, soft

sculptures of knotted rice paper in the form of malleable nets, originally

exhibited in London (Signals Gallery, 1966); and the Graphic Objects 1967 - 1968, a group of works

that explore language and poetry and were first shown at the 1968 Venice

Biennale.

Other important works in the show are Schendel’s early

abstract paintings, among them Tate’s Untitled 1963; her later monotype

drawings on rice paper, of which she made over 2000; and the installations Still Waves of Probability 1969 and Variants 1977. Schendel’s final complete

series of works, abstract paintings entitled Sarrafos 1987, are also included. The Sarrafos are white monochromes with a

black batten extending from their surface, addressing the body, space and

environment of the spectator.

Mira Schendel was born in Zurich in 1919 and lived in Milan

and Rome before moving to Brazil in 1949. She settled in São Paolo in 1953,

where she married Knut Schendel, and where she lived and worked until her death

in 1988. Although brought up as a Catholic, Schendel was persecuted during WWII

for her Jewish heritage. She was forced to leave university, due to

anti-Semitic laws introduced in Italy, and flee to Yugoslavia.

Schendel’s early experience of cultural, geographic and

linguistic displacement is evident in her work, as is her interest in religion

and philosophy. She developed an extraordinary intellectual circle in São Paulo

of philosophers, poets, psychoanalysts, physicists and critics – many of them

émigrés like herself – and engaged in correspondence with intellectuals across

Europe, such as Max Bense,

Hermann Schmitz and Umberto Eco. Among key exhibitions

featuring Schendel’s work were the first and numerous subsequent editions of

the São Paulo Bienal; the 1968 Venice Biennale; a solo show at the Galeria de

Arte SESI, São Paulo (1997); and Tangled

Alphabets with León

Ferrari at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2009).

Mira Schendel is

organised by Tate Modern and the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo in

association with the Fundação de Serralves - Museu de Arte Contemporânea,

Porto. It is curated by Tanya Barson from Tate Modern and Taisa Palhares from

the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo.

http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/mira-schendel

UNTITLED ( GENESIS ) 1965

9 Monotypes on Paper Between 2 Perspex

Sheets, Pins and Nylon Fishing Wire

Dimensions: Right Panel of 4 Monotypes:

612 x 1237 x 8 mm

Left Panel of 5 Monotypes: 612 x 1537 x 8 mm

Individual Monotypes: 465 x 229 mm

Left Panel of 5 Monotypes: 612 x 1537 x 8 mm

Individual Monotypes: 465 x 229 mm

Collection: Tate

Acquisition: Presented by the American

Fund for the Tate Gallery 2012

MIRA SCHENDEL’S GESTURE: ON ART IN VILEM FLUSSER’S THOUGHT,

WITH ‘ MIRA SCHENDEL ‘ BY FLUSSER

By Nancy Ann Roth

3 April 2014

In his theory of communication, philosopher and writer Vilém

Flusser (1920–1991) referred to art often, yet unsystematically. This article

proposes that Mira Schendel, with whom he had an extended dialogue in the

1960s, was a point of reference for him, substantially informing many aspects

of his thinking about art. Also included is a new translation of an essay on Schendel

by Flusser.

‘’ If you lie in wait for a word at the moment it comes out

of the mouth, try to catch it, to chew it before it is spit out (and that would

actually be to grasp the gesture of speaking), you notice that you are always a

second too late. ‘’

Vilem Flusser 1

Vilem Flusser 1

‘’ The works currently on display have resulted from a

hitherto frustrated attempt to catch the discourse right at the moment of its

birth. My concern is with capturing the transfer of the instant living

experience, full of empirical vigour, onto the symbol imbued with memorability

and relative eternity. ‘’

Mira Schendel2

Mira Schendel2

Vilém Flusser (1920–1991) is currently best-known as a theorist

of new media, a term he would have defined as ‘communication technology since

photography’. However, he most often described himself as a writer and his

project as a comprehensive theory of human communication, terms that are

considerably more helpful in grasping his sense of art as movement, as a

particular expression of human consciousness and not as a set of objects.

A native of Prague, Flusser emigrated to Brazil in 1940,

then returned to live in Europe in 1972. When his first book, Língua e

Realidade (Language and Reality) was published in Brazil in 1963, his main

focus was on the criticism of literature. But he wrote criticism of specific

art exhibitions, both in Brazil and later, after he returned to Europe. He

participated in the planning and promotion of the São Paulo Bienale, and later

contributed to the American art journals Artforum International and Leonardo.3 A

reader of his many books and articles on an eclectic range of subjects will

nonetheless be puzzled by references to art that sometimes dismiss, sometimes

prescribe, and sometimes embrace art as tantamount to creativity itself,

equivalent to what we think of as human.4 There

is no comprehensive theory. The closest equivalent is a description of artistic

gesture, a pattern of movement associated with a particular kind of

consciousness. But in this way, art does figure in a very comprehensive theory,

for Flusser’s theory of gesture proposes nothing less than a new way of

defining and valuing the way human beings make and share meaning.

The foregoing remarks are vulnerable to the charge of

anachronism, for they draw on an idea of gesture that seems unlikely to have

figured in the direct exchange between Flusser and Schendel, that is, in the

actual, face-to-face conversations that took place on the terrace of the

Flussers’ apartment in São Paulo between the 1950s and early 1970s. Among the

few sources of information about the exchange is the short essay ‘Mira

Schendel’ that is part of Flusser’s autobiography, Bodenlos [rootless

or foundationless] and is reproduced here as an appendix.5 Although Bodenlos was

not actually published until 1992, it was written in the early 1970s, when

Flusser was literally and figuratively between Brazil and Europe, reflecting on

the immediate past in anticipation of imminent change. The text of ‘Mira

Schendel’, which appears in the section titled ‘Dialogues’, describes an

emotionally turbulent yet sturdy friendship.6 He

assures us that Schendel always controlled the content of the conversations,

and that the topic was always her work. To take him at his word, then, it was a

situation in which he was obliged to think from her point of view, to enter

into the intensity, the emotional volatility, the uncompromising materiality of

her way of being in the world. He says that relationship taxed his patience; it

would seem it taxed her patience as well. For although she had a very high

regard for at least one earlier statement he had written about her work,7 what

she read in the manuscript of the text in Bodenlos made

her angry: the time of frequent and intense discussion between them had largely

ended, even before Flusser and his wife left Brazil.8

Schendel continued, nevertheless, to be a force in Flusser’s

thinking. The two quotations reproduced above, both very difficult to date with

any certainty, provide evidence of a shared interest in a very subtle, very

ephemeral event, in ‘catching’ something intangible – a thought, an idea – long

enough to make its meaning available to others. ‘Catch’ – the same verb in both

quotations – seems to involve a physical, embodied movement, returning again to

the idea of a gesture, a physical movement, as distinct from an object. There

is no point in asking which of the two thoughts came first, or which ‘caused’

the other: Flusser categorised his exchange with Schendel as a dialogue, a term

he consistently defined, first, as a free, interested exchange of information

between two different memories, and, second, as the one and only way human

beings can create something genuinely new. Just by putting the statement about

Schendel in the ‘Dialogues’ section of the book, he was ascribing a very high

value to what had transpired between them. And he went on to be more specific:

‘For Mira, I am a genuine critic’, he wrote. ‘I influence her work. And she

presents me with genuine issues that need to be thought and worked through.’9

Schendel’s impact on Flusser cannot be definitively

‘proven’. Among other reasons, he notoriously failed to acknowledge sources in

his published texts. But Schendel raised ‘genuine issues’, and the loss of

direct contact in itself would not have resolved them. In any case, by

heuristically supposing Schendel to have been ‘there’, present in his thinking,

Flusser’s widely dispersed, even apparently contradictory references to art

seem to coalesce and to suggest the scope of the demands Schendel’s project

made on his theory.

UNTITLED 1966

Ecoline and Oil Pastel Stick on Paper

Dimensions: 430 x 610

Private Collection © The Estate of

Mira Schendel

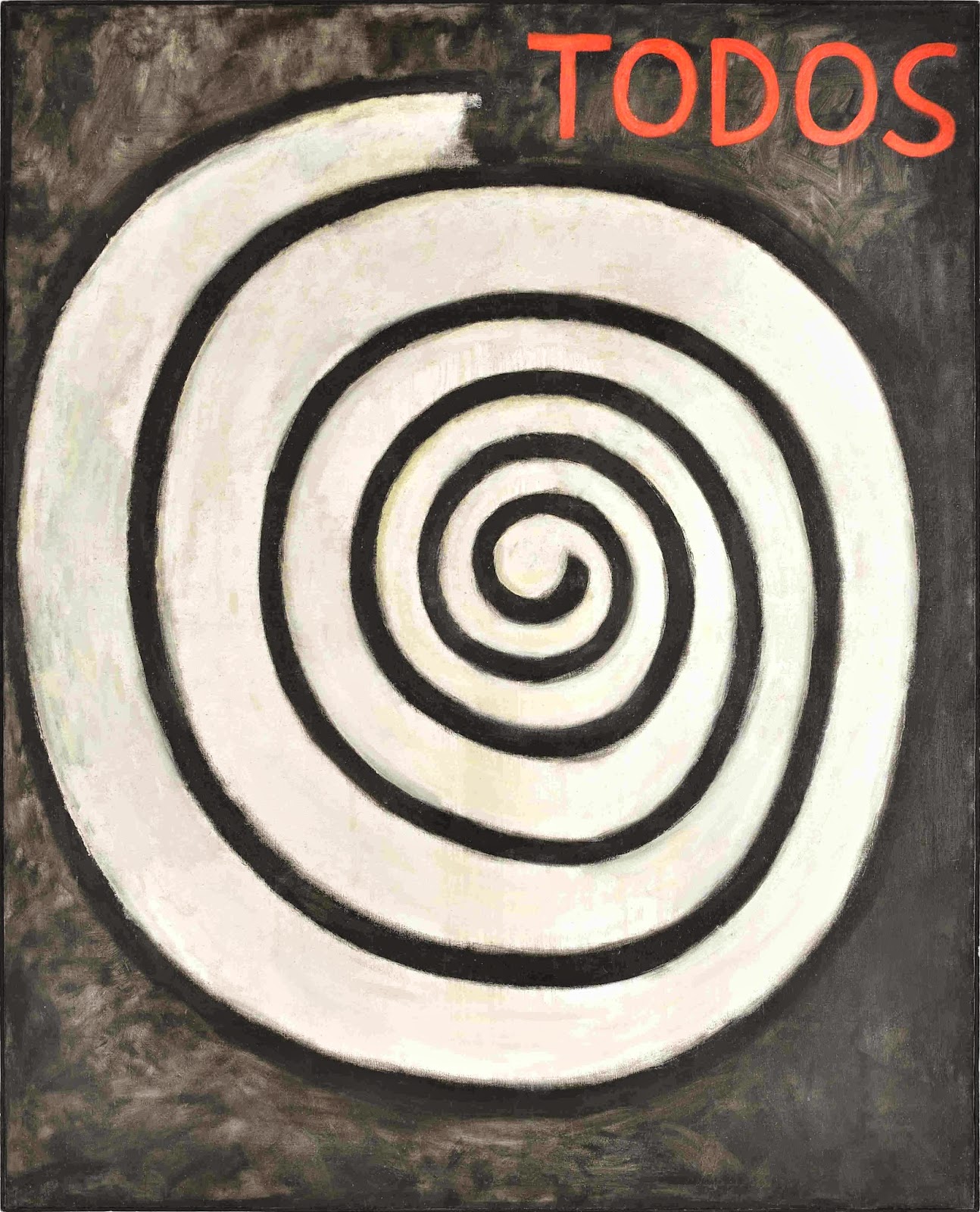

UNTITLED ( TODOS ) 1960 - 1965

Private Collection © The Estate of

Mira Schendel

Photo by Ricardo Ruikauska

GRAPHIC OBJECT 1967 - 1968

Daros Latin America Collection, Zurich

© The Estate of Mira Schendel

UNTITLED FROM THE SERIES DROGUINHAS

C.1964 - 1966

Japanese Paper

Dimensions: Variable, Approximately 90

x 70 cm

Credit Line: Scott Burton Fund

Copyright:© 2015 Estate of Mira

Schendel

Photo Credit Tate Photography

MIRA SCHENDEL’S GESTURE: ON ART IN VILEM FLUSSER’S THOUGHT,

WITH ‘ MIRA SCHENDEL ‘ BY FLUSSER

ByNancy Ann Roth

TRADITIONAL & TECHNICAL IMAGES

Schendel and Flusser were only a year apart in age. For

both, German had been the language – or one of the languages – of childhood,

and Judaism had been a factor in their earliest religious experience, although

Schendel was educated in Catholic schools. Both had been the object of

religious persecution, and after emigrating to Brazil, in 1940 and 1949,

respectively, they shared the status of ‘expellees’. Flusser used the term in

his well-known essay, ‘Exile and Creativity’ to describe people in a completely

unfamiliar situation, constantly confronted with such vast quantities of new

information as to have to filter and shape it creatively in order to survive.10 Both expellees had had to abruptly

abandon their formal education, and although both investigated the possibility

of going back to earn formal qualifications, both decided against it,

preferring to pursue a broad range of studies independently, guided by

immediate interests, needs and opportunities. Among these was a keen

awareness of language itself.

They were hardly alone. Abruptly plunged as they were into a

completely new culture, they surely felt the force of language with exceptional

intensity. But a heightened consciousness of language was noticeable across

diverse disciplines and institutional contexts at that moment, noticeable

enough to acquire the name the linguistic turn, the title of an

influential collection of philosophical essays published in 1967.11 The

date falls comfortably within the timespan of conversations with Schendel on

the Flussers’ terrace in São Paolo, and there are grounds for supposing some

resonance with the heightened awareness of language that was felt at that

particular moment in art as well as philosophy, in Europe and the United

States. And yet Flusser’s dialogue with Schendel, grounded in a quite extensive

shared cultural – and arguably especially religious – memory, seems to have

facilitated a radical rethinking of the way concepts relate to art.

Flusser was relatively new to art criticism when he met

Schendel. As he had long since adopted phenomenology as his main philosophical

method, however, he may well have tried, in keeping with the philosopher Edmund

Husserl’s epoché, or reduction, to ‘bracket out’ whatever

assumptions he brought to the table regarding the relationship of image to

text. Above all, he may have felt philosophically

obligated not to try to attempt any causal ‘explanation’ of

Schendel’s work. The project would rather be to enter into Schendel’s position,

to gain some insight into the challenges she faced by seeking parallels between

his practice as a writer and hers as a maker. It would have raised the

relationship between text and image as a central issue. And here, writer and

artist did have some common ground. As Geraldo de Souza Diaz points out in his

excellent monograph on Schendel, published in 2000:

Many artists were integrating writing into their images in

the 1960s, if in most cases merely as a formal element. But Schendel’s interest

in the relationship between writing and images can be satisfactorily explained

on religious grounds, for from childhood she had been familiar with the ban on

images as well as the language mysticism that underpins the Jewish concept of

God.12

Flusser clearly shared Schendel’s familiarity with these

aspects of Jewish thought, for the ban on images figures prominently in his

subsequent writing. In fact, he seems never to have seriously doubted that

writing is fiercely and intractably antagonistic toward images. Given a

phenomenological understanding of the relationship of consciousness to its

objects, this intractable antagonism became the basis for his history of

communications media. In this view, writing always sought to dominate images –

or more exactly, writing consciousness tried to dominate image consciousness.

It took a long time: ‘Only in the eighteenth century, after a

three-thousand-year struggle, did texts succeed in pushing images, with their

magic and myth, into such corners as museums and the unconscious.’13 But

by the time of Flusser’s own writing, in the 1980s, the tables were again

turning not exactly back to previous conditions but definitely against

writing.

For whereas writing is capable of channelling, controlling

the meaning of traditional images such as drawing and painting, it cannot

control the meanings of images produced by cameras, video recorders and

synthesizers. This is the difference Flusser makes between traditional and

technical images. Cameras, sound recorders and synthesizers – in his word,

‘apparatuses’ – can penetrate past what human beings can actually see or hear

or touch. They reach in to a level at which the world is a mass of whirling

particles, meaningless in itself. The apparatus can confer a meaning. Most

technical images are still made and used as if they were traditional (in

particular, photographs are still ordinarily understood and used as if they

were paintings or drawings). But technical images potentially store more

information, manipulate and distribute it far faster and more efficiently than

linear, alphanumeric text ever could. Flusser’s writing is not rich in specific

examples, but it seems useful to think of images that consolidate scientific

data visually, assigning visual qualities – shape, scale, colour – to, say,

measurements of speed or temperature, creating an image from information that

no one could possibly ‘see’.

The theory of technical images was elaborated after direct

dialogue with Schendel had ended. And yet the idea seems to be there in outline

form already in the early 1970s, in the short essay ‘Mira Schendel’, where it

is implied that her images are no longer ‘traditional’:

Traditionally, thinking goes something like this: I

encounter something concrete. I form an image of this concrete thing (I

‘imagine’ it), so as to acquaint myself with it. And then I translate my image

into a concept, so as to understand the concrete thing and be able to handle

it. Historically, the phase of imagining is the mythical-magical one, and the phase

of understanding is the epistemological-technical one. (In fact this briefly

describes the structure of Western civilisation.) With Mira, it comes to a

qualitative reversal. She starts from the concept and tries to imagine

it. She uses her imaginative powers to make the world of ideas concrete,

rather that to grasp the world of concrete things (for this world slips through

our fingers). One aspect of the contemporary world of ideas is that it has

become unimaginable. This has a great deal to do with our alienation: we cannot

imagine what our ideas (for example, our scientific ideas) mean. A new kind of

imaginary power is required to do it, and Mira mobilises this new power for us

… To make a concept into an image is to turn what is diachronic into something

synchronic, to collapse a process. Mira’s works, which make concepts

imaginable, are the first steps toward a revolution in human existence.14

It also seems clear that Mira did not make what Flusser

termed, in retrospect, ‘technical images’, for Flusser defined them as images

made by an apparatus. Still, he writes that her images reverse the

‘traditional’ relationship of images to texts. As he describes it, her ‘things’

(more on the difficulty with the designation ‘work’ below) are not available to

theorisation or explanation: in some sense, they already are theory. In fact,

Flusser takes considerable care to avoid the presumption of explaining her

work. He doubles up his discussion, so that two perspectives, roughly ‘his’ and

‘hers’, appear: the description of the content of their verbal dialogue might

be considered ‘his’, and the close visual descriptions of the two pieces, one

Graphic Object and one Notebook, are ‘hers’. The text closes with a passage

that positions Schendel’s project roughly in parallel to his own, both being

responses to a shared contemporary situation. Her ‘voice’ is her work.

Flusser is not alone among media theorists in associating

writing with a particular form of consciousness, or in projecting a culture

after writing, a time when writing becomes a rather esoteric skill, if not altogether

extinct. He does appear to be unique in his sense of antagonism between writing

consciousness (he calls it ‘historical’ consciousness) and image-based

consciousness. Nor is it a conflict that has been resolved in the past. On the

contrary, he experiences it as a regular feature of his own – and presumably

others’ – writing. An idea comes in the form of an image.15 In

order to write the idea down, he must attack it, shattering it into word-scaled

pieces, forcing it to follow the grammatical and orthographic rules of a

specific language. His description of Schendel’s procedure suggests something

like the reverse, only in some ways also a move forward. He reaches a concept

by writing it; she goes on to turn a concept to a new kind of image.

Rather than the conventional relationship between artist and

writer, then, in which the writer writes about and explains the

artist’s work, Flusser suggests a sense in which the image might supersede

writing, in which the artist might imagine the writer’s idea, and in which

writing could disappear.

THE TATE MODERN LONDON

THE TATE MODERN LONDON

In December 1992 the Tate Trustees announced their intention

to create a separate gallery for international modern and contemporary art

in London.

The former Bankside Power Station was selected as the new

gallery site in 1994. The following year, Swiss architects Herzog & De

Meuron were appointed to convert the building into a gallery. That their

proposal retained much of the original character of the building was a key

factor in this decision.

The iconic power station, built in two phases between 1947

and 1963, was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. It consisted of a stunning

turbine hall, 35 metres high and 152 metres long, with the boiler house alongside

it and a single central chimney. However, apart from a remaining operational

London Electricity sub-station the site had been redundant since 1981.

In 1996 the design plans were unveiled and, following a £12

million grant from the English Partnerships regeneration agency, the site was

purchased and work began. The huge machinery was removed and the building was

stripped back to its original steel structure and brickwork. The turbine hall became a dramatic entrance and display area

and the boiler house became the galleries.

Since it opened in May 2000, more than 40 million people

have visited Tate Modern. It is one of

the UK’s top three tourist attractions and generates an estimated £100

million in economic benefits to London annually.

In 2009 Tate embarked on a major project to develop Tate Modern. Working

again with Herzog & de Meuron, the transformed Tate Modern will

make use of the power station’s spectacular redundant oil tanks, increase

gallery space and provide much improved visitor facilities.

http://www.tate.org.uk/about/who-we-are/history-of-tate

THE TATE MODERN LONDON

MIRA SCHENDEL’S GESTURE: ON ART IN VILEM FLUSSER’S THOUGHT,

WITH ‘ MIRA SCHENDEL ‘ BY FLUSSER

By Nancy Ann Roth

ART & INFORMATION

In the Bodenlos article, Flusser acknowledges

Schendel as a great artist. Yet the analysis that follows makes no particular

reference to art. With certain notable exceptions to be discussed below, when

Flusser discusses art in his writing, he invariably does so from the ‘outside’,

from the position of a critic, observing, listening, and receiving. Perhaps

particularly in the books published in the 1980s, he writes as someone who sees

art as one kind of message, that is, as information. In broad outline, the

theory he advances defines information in terms of probability and

improbability: the more improbable a given event or object is, the more

informative. In this context, human being are engaged in a kind of permanent

struggle against the forces of entropy, the overall tendency of the world

to gradually lose information, so that everything becomes more and more

probable, predictable. The tendency to resist entropy, negentropy, is another

word for creativity. Nature created the world – very slowly – and continues to

create at the rate improbable events occur, rarely and randomly. But human

beings are capable of creating – which is to say of generating new information

– much more quickly and deliberately.17 They

can do it under one simple, but absolute condition: there must be dialogue. New

information comes exclusively from dialogue, that is, from a free exchange of

information between two memories. The two memories may be aspects of a single

mind – a possibility that largely accounts for the ‘lonely genius’ model of

creativity. There may also be a dialogue between an organic, human memory and

an artificial one, such as a library or archive or memory stored on a server.

But the really exciting form of creativity involves an exchange between two

human memories – provided these are free and equal rather than forced or

predetermined. His concern for the immediate future is that in our society,

reliant as it is on forms of communication that are increasingly automated,

genuine dialogue is becoming close to impossible: a society that does not

generate new information will become completely predictable – and humanly

unbearable. It is in the interests of preserving the possibility of dialogue

(creativity), then, that Flusser discusses the task of art criticism, again,

with the tools of information theory: the more improbable and informative a

given gesture may be, the higher its value as art – and this will be the case

whether the object in question in an image, musical performance, new algorithm,

scientific insight or business plan. Treating art as information leads him to

some startling and irreverent conclusions, for example, the possibility that

our inherited concept of art effectively blocks our perception of new,

especially new digital images,18 or that the idea of

an avant-garde, just by virtue of its isolation, is ‘ridiculous’.19 But

perhaps more startling than either of these is the insistence that any future

art criticism will have to accommodate the tendency for new information to

become old, familiar – it will have to take the formation of habit into

account.20

The engagement with information theory does not, on the

surface, seem to involve Schendel. It is highly abstract, impersonal, and the

relationship with her was neither. What links the two is clearly

dialogue. In the sustained concern with Schendel’s on-going project, with her

thinking and experimenting, elations, frustrations, demands and above all

persistence, Flusser had seen the force of dialogue for himself, experienced it

producing new information, in this case new both highly improbable objects and

equally improbable ideas. He could write about creativity and dialogue with

phenomenological confidence.

He would, further, resist any thought that dialogue might

diminish difference, might blur the distinct features, the identities of the

separate participants. It comes to something of a test in his vision of artists

of the future (no longer called ‘artists’, for in the universe of technical

images they are so different from traditional artists as to have acquired the

name “Einbildner’ or ‘envisioners’). After warning us about the tendency of

technical images to steer us toward intolerable sameness and boredom, Flusser

goes on to envision them used creatively, that is, in dialogue. Toward the end

of Into the Universe of Technical Images (1985), he treats himself

to a rather extravagant vision of how this might look (the weakness of the term

‘images’ is exposed here, because the material being exchanged might be

acoustic or tactile, as well as visible). In his description, the exchange is truly

exhilarating – like musical improvisation in multiple dimensions, sensitive to

harmonies and dissonance, to the particular strengths and weaknesses of the

particular players, totally absorbing, culminating in a joyous suspension of

self-awareness.21 Yet

Flusser insists that such creative exchange does not result in any diminished

sense of self but that, on the contrary, it provides the ideal conditions for

recognising, acknowledging and appreciating what is singular, unique about any

one person’s characteristic contribution. Even in this rather fantastic bit of

science fiction, then, Flusser does not contradict his own direct experience

of dialogue.

http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/mira-schendels-gesture-on-art-vilem-flussers-thought-mira-schendel

UNTITLED 1980

Private Collection © The Estate of

Mira Schendel

Photo Credit Tate Photography

Photo Credit Tate Photography

UNTITLED 1962

Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 74.9 x 74.7 cm

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The

Adolpho Leirner Collection of

Brazilian Constructive Art, Museum Purchase ©

The Estate of Mira Schendel

STILL WAVES OF PROBABILITY 1969

Nylon Thread© Mira Schendel Estate

Nylon Thread© Mira Schendel Estate

Installation

View at Tate Modern, London, 2013

Photo Credit

Tate Photography

UNTITLED ( DISKS ) 1972

Letraset, Graphite on Paper and Transparent Acrylic

Dimensions: Support 270 270 7 mm on Paper, Unique

Lent by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery 2007

© The Estate of Mira Schendel

Letraset, Graphite on Paper and Transparent Acrylic

Dimensions: Support 270 270 7 mm on Paper, Unique

Lent by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery 2007

© The Estate of Mira Schendel

STILL WAVES OF PROBABILITY 1969

Nylon Thread© Mira Schendel Estate

Nylon Thread© Mira Schendel Estate

Installation View at Tate Modern, London, 2013

Photo Credit Tate Photography

UNTITLED 1963

Presented by Tate Members 2006

© The Estate of Mira Schendel

© The Estate of Mira Schendel

VARIANTS 1977 ( DETAIL )

VARIANTS 1977

Oil on Rice Paper and Acylic Sheets

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Adolpho Leirner Collection of

Oil on Rice Paper and Acylic Sheets

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Adolpho Leirner Collection of

Brazilian Constructive Art © The Estate

of Mira Schendel

VARIANTS 1977 ( DETAIL )

MANDALA 1974

Private Collection © The Estate of

Mira Schendel

Photo by Ricardo Ruikauska

Photo Credit Tate Photography

GRAPHIC OBJECT 1967 - 1968

Daros Latin America Collection, Zurich

© The Estate of Mira Schendel

GRAPHIC OBJECT 1967

Collection Patricia Phelps de Cisneros

© The Estate of Mira Schendel

Max Bense was

the only one who understood that… these things didn’ t function as objects,

because all that mattered was the light and shadow, a continuation of some

drawings of mine, those done on that ultra fine, transparent paper.

Mira Schendel

MIRA SCHENDEL’S GESTURE: ON ART IN

VILEM FLUSSER’S THOUGHT,

WITH ‘ MIRA SCHENDEL ‘ BY FLUSSER

By Nancy Ann Roth

GESTURE & AND THE ARTISTIC LIFE

If information theory seems to gain and lose prominence in

Flusser’s thought over time, his grounding in phenomenology is constant. One of

the best examples is his persistent engagement with the thoroughly

phenomenological idea of gesture. The three books in which he outlined his

theory of communication appeared in quite rapid succession, in 1983, 1985 and

1987, respectively.22 The

volume titled Gesten (Gestures), first published in 1991, ‘traces

back to years of talks and courses Vilém Flusser gave in São Paulo and Aix-en-Provence’.23 The

book bears witness to a striking continuity in his thinking. It suggests

someone moving around his objects of study – a bit like the photographer he

describes in ‘The Gesture of Photographing’ moving around his subject, changing

the distance, changing the angle, finding what he may not have quite known he

was seeking. The book consists of eighteen essays. Two are introductory, and

sixteen bear the title, ‘The Gesture of …’. Many of the gestures correspond to

established ‘media’, for example, writing, painting, videoing or filming. Some,

such as ‘The Gesture of Planting’, take up a broad historical shift in social

consciousness, in this case the rise and spread of ecological awareness. Still

others examine such repetitive, familiar movements as shaving.

‘The Gesture of Writing’ comes first after the

introductions, and, in this context, it quickly becomes identifiable as an

analysis of Flusser’s own most characteristic gesture – the one through which

he articulates his own way of being in the world most effectively. From here,

we move out, with him, either as participants or as spectators of the various

gestures, and Flusser takes care to state his own experience – or lack of it –

in each case. ‘The Gesture of Painting’, for example, is written from the

standpoint of someone observing a painting-in-progress, for Flusser did not

paint. In fact, within the collection, ‘The Gesture of Painting’ presents a

kind of primer in the phenomenological method, the careful bracketing out of

prior knowledge about the matter at hand. It starts with a deliberate refusal

to accept that the painter is the ‘cause’ of the painting, or even that the

‘painter’ can be regarded as separate from his or her brush or pigment or

canvas. The memorable conclusions he reaches here include the idea that a

painter is really only a painter in the gesture of painting itself, in the

actual movement.

Nothing in ‘The Gesture of Painting’ contradicts the memory

of Schendel. And yet her presence seems far stronger in another essay, “The

Gesture of Smoking a Pipe’. The title hardly announces any discussion of art,

and so it comes as something of a surprise to find Flusser using pipe-smoking

to establish both a weak connection and a very sharp distinction between

himself and a ‘real’ artist. For, of course it is Flusser himself who is

the pipe-smoker.

The essay is concerned with a classification of gesture, and

more particularly with the classification of ritual gesture. The broad

contention – argued in more detail elsewhere – is that, with allowances for

overlap, a given gesture will belong to one of three broad categories: work,

communication or ritual. He argues that pipe-smoking belongs to the third

category, ritual – defined as a gesture that is meaningful without either

changing anything, as work is intended to do, or communicating anything. This

furnishes the occasion to look more closely at ritual, and in particular at

religious ritual. He emphasises how Jewish tradition in particular guards

zealously against any association between its rituals and, for example, magic –

for magic seeks to have an effect in the world, and so constitutes a form of

work. He himself seems somewhat startled to conclude that ritual gesture is

essentially aesthetic – not concerned to change the world or to communicate

anything but to ‘act out’ a unique way of being in the world. And it is on this

last point that his pipe-smoking is drawn into the comparison – because it,

too, is only an expression of a singular, personal set of judgements with no

further ambitions. Pipe-smoking is exposed as a pale, small example of ritual,

only just enough to appreciate the kind of gesture that dominates ritual lives,

the lives of priests, prophets – and artists:

It will be apparent to anyone who has ever made such a [ritual]

gesture that we recognize ourselves in them, and only in them: only in piano

playing, only in painting, only in dancing does the player, the painter, the

dancer recognize who he is. It is a founding principle of Zen Buddhism that

self-recognition can be a religious experience, if the recognition is of the

‘whole’ self: its rituals (tea drinking, flower arranging, board games) are

therefore sacred rites. Certainly the greatest discovery of Jewish prophesy is

that religious experience is an experience of the absurd, the groundless, that

‘God’ is manifest as that which is inexplicable, indefensible, ‘good for

nothing else’: hence its battle against magic and its insistence on the absurd

rite, with no aims that make any sense. But all these noble insights, those of

the artist, the Zen monk and the prophets, can be gained in a modest and

profane way by watching such everyday gestures as pipe smoking with sufficient

patience. For then it becomes clear how each of us is a virtual artist, and a

virtual Zen monk, and a virtual prophet. For each of us performs purely

aesthetic, absurd gestures of the same type as smoking a pipe. What also

becomes clear, of course, is what sets us most of us apart from real artists,

Zen monks and prophets: namely the complete renunciation of reason (in the

sense of explicability and purpose) and the unconditional surrender in the

gesture and to the gesture essential to the real artist, the real Zen monk, the

real prophet.24

The real artist, then, is someone who lives in ‘renunciation

of reason and the unconditional surrender in and to the gesture’. It is someone

quite different from a person for whom the aesthetic gesture is superficial, as

pipe-smoking was for Flusser himself. I contend that Mira Schendel had shown

him such a life. She presented him with a challenge of such intensity and

consistency that it burst the boundaries of any understanding of art available

to him at the time. He was forced to develop another. In a sense, he

never recovered the lost boundaries, for they dissolved in the much broader

context of gesture. As gesture, art emerged as a particular kind movement, an

expression of a one kind of intention rather than a vast inventory of objects,

or ‘works’. Set free of physical objects, art flows out of dedicated

institutions and becomes a particular dimension, an intensity, a level of

commitment potentially available in any human activity at all.

http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/mira-schendels-gesture-on-art-vilem-flussers-thought-mira-schendel

%2B1965.png)

.png)

+1972.jpg)